烟火起成村

2022-06-08李郁葱

李郁葱

唐人对运河的观感大概是矛盾的,前朝的兴亡犹在眼前,而对于大的治国方略常人并不会理解,或不想去理解。隋炀帝开凿运河在后世看来有其深思熟虑,但冒进导致王朝的崩溃却是不争的事实。

在我们看到的唐代诗文中,关于运河的笔墨大都和白居易(772-846年)新乐府诗《隋堤柳》相似:“后王何以鉴前王?请看隋堤亡国树。”

而杭州在隋唐之际,因为自然形成较迟的原因,尽管已是名郡,存在感却相对较弱,隔着钱塘江,就是一直以来大名鼎鼎的会稽郡。为了两地的高下之分,白居易和好友、时任浙东观察史的元稹甚至打过诗词笔仗。但那个时代的运河实际上已经成为漕运的主干道,民间多年来称其为隋炀帝运粮河。白居易牧钱塘时所写的两篇祭神文,也与之有着千丝万缕的关系。在多年之后,白居易写的三首《忆江南》中,也隐约可见运河的影子:“江南好,风景旧曾谙;日出江花红胜火,春来江水绿如蓝。能不忆江南?”

从白居易的祭神文中,我们大抵可推测出当年运河湖墅段的影像。按照可以查阅到的资料,杭州早在南朝之时就已是天下粮仓之一,“大贮备之处”的“钱塘仓”业已成形,而杭州的航运异常发达,《隋书 · 地理志》说到的杭州是:“川泽沃衍,有海陆之饶,珍异所聚,故商贾并凑。”

祈雨:唐代官员的政绩考核项目

“骈樯二十里,开肆三万室”,这是和白居易差不多同一个时代的李华在《杭州刺史厅壁记》中所記,而略晚于白居易的杜牧(803年—约852年),在《上宰相求杭州启》中说,杭州每年税钱五十万缗(约占全国一年财政收入的二十四分之一),其中有相当部分应取自过往运河的舟船。

白居易到杭州的时间节点并不好,公元822年,正逢江南大旱。大旱之年,水资源的分配就成为摆在地方官眼前的难题 :江南运河漕运和沿岸农田灌溉,都面临无水为继,两者之间有矛盾之时,又当如何取舍?

唐代有个在后世看来很奇葩的规矩,在当时却是一件正经事:在吏部的考核中,官员祈雨是作为政绩考核中的重要一项,做得不到位还有免职的风险。从个人来说,白居易本身是笃信佛法的居士。

在这种种原因的促使下,白居易决定先去杭州城北的皋亭山祈雨,甚至还一本正经地记录在册。早在杭州大部分地区还是一片汪洋大海时,皋亭山已兀立海上,南麓的皋城遗址中曾出土过良渚文化的凿、刀、犁等石器及陶鼎足等。皋亭山古有皋亭神,为皋亭山周边人的崇拜主神。

近年也有人考证认为皋亭神是项羽的假托之神,顺便一提。

白居易通知了余杭县令常师儒,让他准备一下,并选好黄道吉日,也就是这一年的七月十六日,然后他自己开始写作传诵于世的《祈皋亭神文》,就在他准备上山昭告皋亭神的前两天,他的好友牛僧孺来到了杭州。这个牛僧孺非一般人,就是后世称为“牛李党争”的主角之一,牛党来自于他的姓。

祈文:白居易用上激将法

到了上山这一天,府衙里的大小官吏除了值守的,都早早聚集起来,队伍很大,还有一些自发的百姓,大家都盼望着能够下一场及时雨,解救大旱灾。

到皋亭山走的是水道,尽管由于连年大旱,运河水位低浅,但出于漕运的考量,运河水保持着一定的水位,便于通航。白居易一行在今天的上塘河上舟向北蜿蜒而行。

两岸烟柳如画,远处山色青青。在白居易离开杭州后所写的《东楼南望八韵》中,这一景色也许一直留存在他的内心,而在文字中倾泻出来。“鱼盐聚为市,烟火起成村。”便是当时运河和钱塘江之间乡村的描述。另外一首在杭州时写的《五月十五日夜月》也可看到运河的轮廓 :“……春风来海上,明月在江头。灯火家家市,笙歌处处楼……”

皋亭山上,余杭县令常师儒和侍奉皋亭神信众早已备好了斋醮礼仪所需要的祭品,这是杭州当时所进行的最大的一场法事了。礼仪繁复而讲究,所祭祷的皋亭神的牌位放在正中,香烟缭绕,灯烛辉煌。当法师做完前面的流程之后,轮到本地最高的行政首脑主祭神灵。面对神位,背对着人群,白居易用高亢饱满的声音诵读他的《祈皋亭神文》:“维长庆三年,岁次癸卯……以酒乳香果,昭告于皋亭庙神……”

这是一篇非常有趣的祈神文。白居易把神灵看作是生活中的一部分,并不高高在上,在祈文中白居易说,在此前一日曾“祷伍相神,祈城隍祠,灵虽有应,雨未沾足”。那边的两个神灵没有满足人们的要求,所以我们改请于皋亭神。

他的言下之意也许是:皋亭神啊,如果你不满足我们的要求,那么我们走着瞧吧!

白居易在祈文中又和皋亭神说,如果你不能解决下界百姓的这个要求,是你这个神仙的耻辱啊!这都用上了激将法了,也许,请不如激!

牛僧孺恰逢其会,白居易请他上山也不是没有目的的,牛僧孺的书法独树一帜,于是请其在祭神仪式结束后书写了祈文,刻在石碑上,勒石于祭祀之处。这石碑现在已无从查考,大约毁于战争和时间。

但雨一直没有下来,人心更为焦虑,这个神不行,我们再换个神吧。半个月后,到了八月二日,白居易祭黑龙神:“若三日之内,一雨滂沱,是龙之灵,亦人之幸。”(《祭龙文》)

在这祈文中,白居易说,答应吧,你难道没有需要帮忙的事情吗?

可见,神和白居易自己是平等的,人有求于神,神也有求于人,人与神休戚与共,同耻同荣。

但神灵们大概是出门走亲戚了,或者对于他们而言,人间的这点疾苦算不了什么。他们是高高在上的神明,有理由漠视着这一切。

祈神:白居易驱虎终于成功

屋破偏逢夜漏雨。在祭完黑龙神后,雨没有下,土地像是一张张委屈而焦渴的嘴,等待着甘霖降落。

余杭县又出事了。原来一直在山中与人相安无事的猛虎下山伤人了,而且发生多起,百姓人心惶惶。当常师儒到州衙禀告此事时,两人商议了下,白居易一方面派驻军去搜寻捕猎,一方面写了《祷仇王神文》:

“……尝闻神者,所以司土地,守山川,驱禽兽,福生人也。馀杭县自去年冬逮今秋,虎暴者非一,神其知之乎?人死者非一,神其念之乎?居易与师儒猥居牧宰……”

在白居易这多次的祈神中,这一次驱虎的祈祷好像成功了,也许是搜寻捕猎的行为让老虎感觉到了危险,反正老虎就此在余杭县失去了踪迹。

但神灵们却没有听见白居易最为迫切的心声:下雨。到了知天命之年的白居易,心里清楚,天帮忙,人努力才是出路……

在白居易整治西湖后所写的《钱塘湖石记》中,其实写到了当时航运和民生之间的矛盾,即“决放湖水,不利钱唐县官”,“鱼龙无所托”,“茭菱失其利”,“放湖即郭内六井无水”等四“云”,是钱唐县官吏反对泄放西湖之水接济运河。白居易“今年修筑湖堤,高加数尺,水亦随加”,这也许调和了两者之间的矛盾,西湖济运,在以后的漫长岁月中也成了江南运河杭州段的铁律。

严格来说,白居易的《钱塘湖石记》里,其实也有运河的影子,就像运河之水和西湖之水,实际上是相通的,它们润泽了杭州这座城。

这就像白居易在杭州的一首酬唱之诗:《苏州李中丞以元日郡斋感怀诗寄微之及予,辄依来篇七言八韵走笔奉答兼呈微之》,诗里有个人暮年壮志未已的无奈,又流露出人生知己好友相交的欢喜,其中“长洲草接松江岸,曲水花连镜湖口”一句,意谓苏杭本为邻,运河一水通。写的时候,白居易可没想到他离开杭州后会成为苏州刺史。

运河:流淌在唐诗之路上

纵观整个唐代的诗文,浩如烟海,而明确写到运河杭州段的却寥寥无几,这大概因为杭州当时只是通往越州(绍兴)、湖州等地的中转站。

在后世传颂的唐诗之路上,运河作为重要的交通枢纽,它又怎么可能少了文人的足迹,甚至可以设想,有很多脍炙人口的诗文就写成于杭州与外郡相通的河面上,或者构思于他们眺望两岸风景之际。

比如顾况和李绅都写过与运河相关的诗。顾况写的诗是《临平坞杂题》中的一首《芙蓉榭》:“风摆莲衣干,月背鸟巢寒。文鱼翻乱叶,翠羽上危栏。”

那时的临平又称藕花洲,种植大量的荷花,与杭州的联系多走水道。李绅在他的《却到浙西》中同样有这样的元素:“临平水竭蒹葭死,里社萧条旅馆秋。尝叹晋郊无乞籴,岂忘吴俗共分忧。野悲扬目称嗟食,林极翳桑顾所求。苛政尚存犹惕息,老人偷拜拥前舟。”

水道纵横,阡陌交错,江南的景色便这样留在文人骚客的记忆里。在离开杭州的许多年后,有一天,在东都洛阳,白居易在仿照江南景色所建的庭院里接待客人,从杭州带回的鹤在池塘中徜徉,友人说起杭州的旧事,他有着无限的惆怅,写下了《答客问杭州》一诗:“为我踟蹰停酒盏,与君約略说杭州。山名天竺堆青黛,湖号钱唐泻绿油。大屋檐多装雁齿,小航船亦画龙头。所嗟水路无三百,官系何因得再游?”

白居易不知道的是,正是因为他对杭州的竭力赞美,杭州湖墅段运河诗文的璀璨年代虽然尚未到来,但很快就会来了。

Poetic Hangzhou Section of the Grand Canal

By Li Yucong

People’s view of the Grand Canal in the Tang dynasty (618-907) was probably contradictory: they seemed to see more clearly the rise and fall of previous dynasties than the governance strategy or the so-called big picture of their time. Admittedly the opening of the Grand Canal by Emperor Yang (569-618) of the Sui dynasty (581-618), judged by later generations, was well thought out, but an indisputable fact is, this move led to the collapse of his own dynasty.

In Tang poetry, the epitome of canal-themed works could be found in Bai Juyi’s (772-846) “Sui Di Liu” (or Willows at the Embankment of the Sui Dynasty), where he adopted a negative and blaming tone. From Bai’s articles on prayer written when he was an official in Hangzhou, we can roughly visualize the canal’s Hangzhou section back then. Besides, according to available historical records, Hangzhou was one of the national granaries as early as in the Southern Dynasties (420-589).

The timing of Bai Juyi’s arrival in Hangzhou was not good. It was in the year 822, when a severe drought hit the Jiangnan (south of the Yangtze River) area. In the wake of the drought, the distribution of water resources became a problem for local officials: with only a limited amount of water resources, which should be the priority, the canal transport or the farmland irrigation along the bank?

In the Tang dynasty, there was a rule — which may seem odd to later generations but was a serious matter at that time — that officials were appraised on how they prayed for rain, and they were likely to be dismissed if they failed to do it properly.

Prompted by all these factors, Bai Juyi decided to go first to the Gaoting Mountain in the north of Hangzhou to pray for rain, which was documented in detail. Bai informed the magistrate of Yuhang prefecture to prepare for the ceremony and choose an auspicious day — the 16th day of the seventh month of that year, and then he himself began to write an article on praying to the God of Gaotong, which became a well recited work that has passed on for generations.

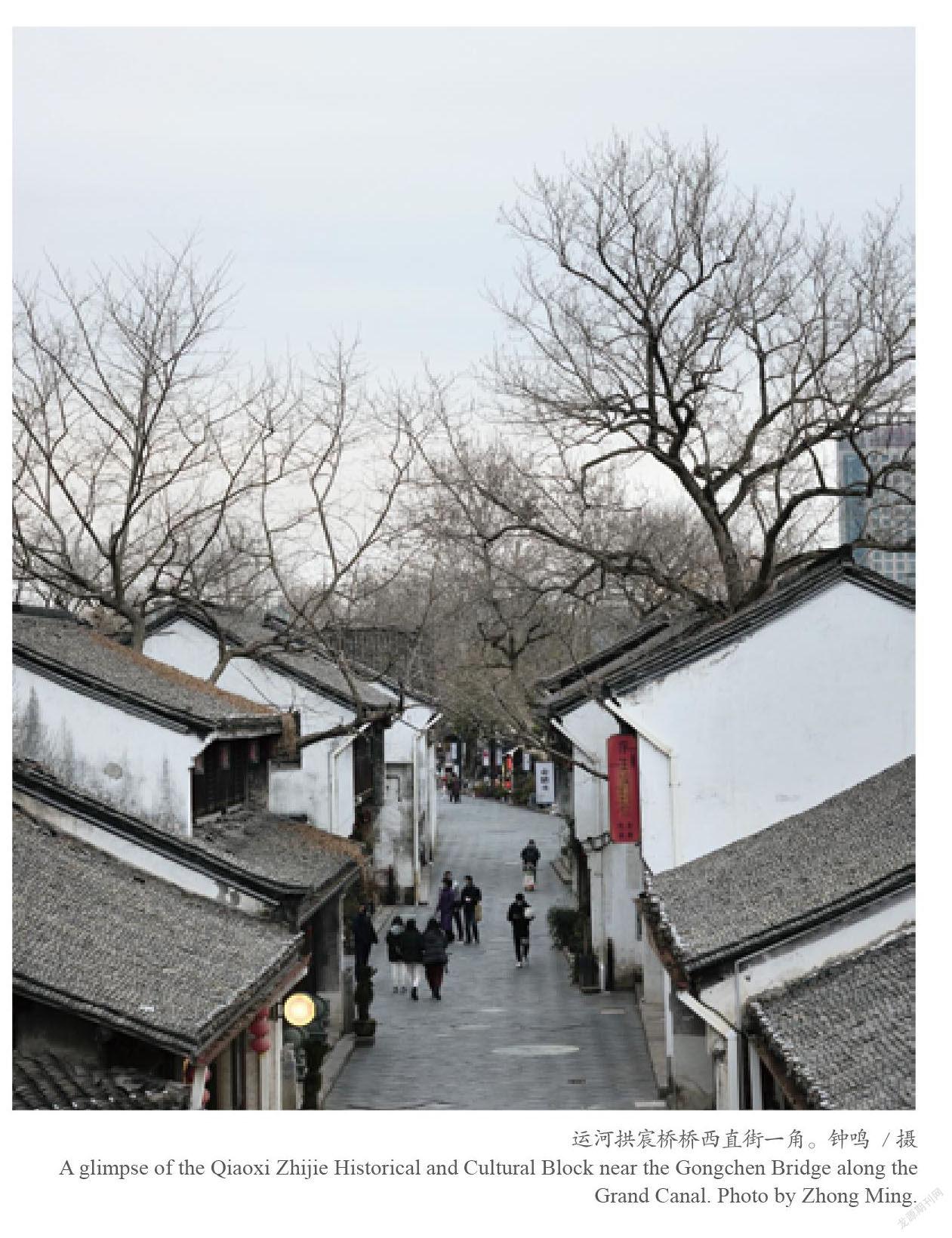

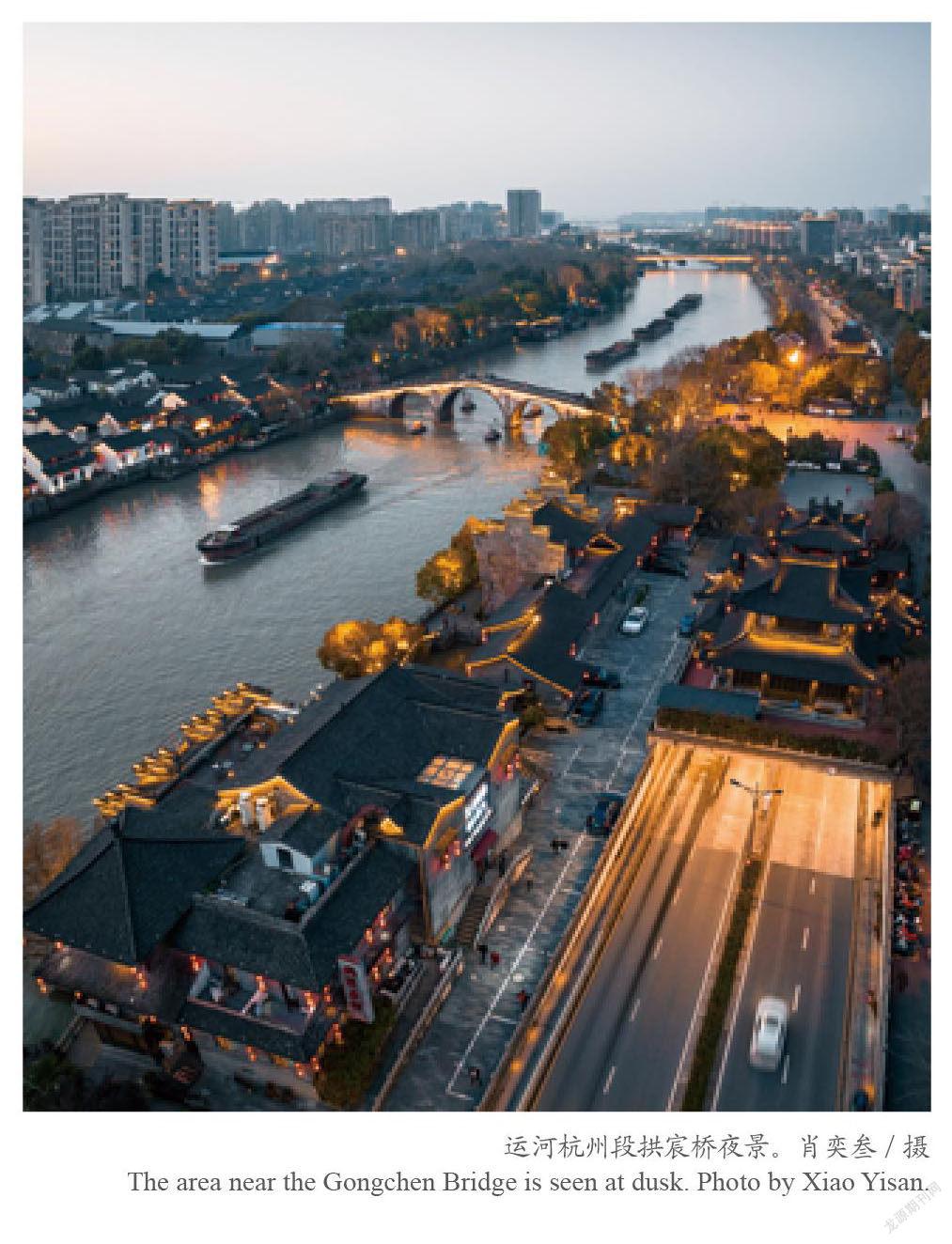

When the big day came, government officials of all ranks, except those on duty, gathered early in a large procession, which was joined by some enthusiastic villagers. They were all hoping for a timely rain to relieve them of the great drought. They got into a boat and headed north for the mountain, accompanied by picturesque willows on both banks and verdant mountains in the distance. It seems that this view was cherished in Bai’s heart and weaved into his poetic fabrics.

On the Gaoting Mountain, the Yuhang magistrate and some faithful followers had already prepared the offerings needed for the ceremony, which was the largest one performed in Hangzhou at that time with the most elaborate rituals. In the middle of the ceremony, Bai recited his article loudly and high-spiritedly. This is a very interesting work, where Bai saw the god as a part of everyday life instead of some superior being. He even dared the god to relive his people of the miserable drought, otherwise it would be a shame for him as a god. However, it still didn’t work.

Half a month later, Bai prayed to the God of Black Dragon. In this prayer, he pleaded hard for his voice to be heard. However, the gods were not there for the people. Maybe in the gods’ eyes, this disaster on earth is unworthy of attention.

With the thirsty land eagerly waiting for the rain to fall, something bad happened again in Yuhang. A tiger that had hidden in the mountains suddenly came down and hurt people several times, and the whole town was in fear. After discussing with the magistrate, Bai Juyi on the one hand sent the garrison to hunt the tiger, on the other hand wrote another article on prayer.

In Bai Juyi’s many such articles, this one to drive away the tiger seemed to be successful. Perhaps it was really the hunting that made the tiger sensed the danger, and the tiger finally disappeared in Yuhang anyway.

But the gods still failed to hear Bai’s urgent request for rain. In his Qiantanghu Shiji (Stone Records about Qiantang Lake) written after he successfully carried out the dredging project at the West Lake, he actually wrote about the conflict between water transport and people’s livelihood at that time: “This year, the lake embankment was fixed by increasing its height for a few feet, and the water level rose therewith.” Strictly speaking, in that article, the role of the Great Canal was somehow only implied, just like the waters of the canal and of the West Lake are actually connected to tenderly support the city of Hangzhou.

Throughout the Tang dynasty, a vast amount of poetry and literature had been composed, but only a few of them are explicitly about the Hangzhou section of the Grand Canal, probably because Hangzhou was only a transit point to Yuezhou (present-day Shaoxing), Huzhou and other places.

It is also reasonable to imagine the bulk of the most popular poems were written by the poets on the river between Hangzhou and other places, or conceived when they were enjoying the scenery on both sides of the river.

The beautiful sight of the Jiangnan area, its crisscrossed waterways and intertwined paths were thus left in the memories of the literati. One day, many years after Bai Juyi left Hangzhou, he received his guests in Luoyang at his Jiangnan-style courtyard. Watching the cranes he brought back from Hangzhou swimming freely in the pond while listening to the guests talking about the old days in Hangzhou, he felt a fit of nostalgia and wrote a poem about it.

What Bai Juyi did not know was that it was perhaps because of his generous praise of Hangzhou, the glittering era of poetic literature about the Hangzhou section of the Grand Canal would come very soon.