Tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis in Iran: A review

2022-05-23SayyedGholamrezaMortazaviMoghaddamAbdolSattarPaghehEhsanAhmadpourAlacsandraBaracAzadehEbrahimzadeh

Sayyed Gholamreza Mortazavi-Moghaddam, Abdol Sattar Pagheh, Ehsan Ahmadpour, Alacsandra Barac,Azadeh Ebrahimzadeh✉

1Infectious Diseases Research Center, Birjand University of Medical Sciences, Birjand, Iran

2Department of Parasitology and Mycology, Faculty of Medicine, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

3Clinic for Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Clinical Centre of Serbia, 11000, Belgrade, Serbia

ABSTRACT

In recent years, the number of cases of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in Iran has increased. The goal of this study was to determine the epidemiological status, clinical symptoms, diagnostic methods, and treatment strategies of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in Iran, with a focus on tuberculosis meningitis and miliary tuberculosis. Between January 1, 2000 and June 1, 2021, 1 651 cases of tuberculosis meningitis and miliary tuberculosis were discovered in Iran. The prevalence of tuberculosis meningitis was higher in Sistan and Baluchestan, South Khorasan, and Mazandaran compared with other provinces. The most prevalent symptoms of tuberculous meningitis were fever, anorexia, headache, neck stiffness, loss of consciousness, and vomiting. The most commonly used procedures for diagnosing tuberculous meningitis were polymerase chain reaction and cerebrospinal fluid culture. The most prevalent clinical symptoms of miliary tuberculosis were fever, lethargy, weariness,and anorexia. In 70% of chest radiographs, a miliary pattern was visible. Bone marrow biopsy was used to diagnose miliary tuberculosis in 80% of patients, while bronchoalveolar lavage was used in 20% of cases. The conventional 6-month treatment approach for tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis was used for all of the participants in the investigations. Given the high prevalence of extrapulmonary tuberculosis patients in Iran and the devastating consequences of the disease, the researchers recommend that further study be done to prevent extrapulmonary tuberculosis in the general population.

KEYWORDS: Extrapulmonary tuberculosis; Tuberculous meningitis; Miliary tuberculosis; Iran

✉To whom correspondence may be addressed. E-mail: ehsanahmadpour@gmail.com;mr14436@yahoo.com

1. Introduction

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) is a type of TB that occurs outside of the lungs. EPTB is found in 10% of western countries and 25% of Eastern Mediterranean countries. HIV and immunosuppression are two main risk factors for the development of EPTB. In recent years, due to an outbreak of HIV, the frequency of EPTB has risen to 35% in some African countries. Brain and central nervous system (CNS) tuberculosis is one type of the serious EPTB[1]. Tuberculosis is one of the oldest infectious diseases caused by Mycobacterium (M.) tuberculosis. Tuberculosis is typically presented with pulmonary involvement. But a significant proportion of cases are extrapulmonary. Tuberculosis of the central nervous system is one of the most dangerous forms of extrapulmonary tuberculosis[2]. Different types of central nervous system involvement include tuberculous meningitis, brain tuberculoma,and TB abscess[3,4]. Tuberculous meningitis is a serious illness that affects 2%-9% of all TB cases and 20% of EPTB cases. Even with proper and approved treatment, 63% of patients with tuberculous meningitis will die[5]. Tuberculosis related intracranial involvement including tuberculoma, vascular thrombosis, ischemia, and proliferative arachnoiditis lead to excessive intracranial pressure and hydrocephalus. Tuberculous meningitis present with signs and symptoms that are similar to sub-acute bacterial meningitis[6,7].

Miliary TB accounts for 1%-2% of all TB and 8% of EPTB cases[8]. Radiology plays an important role in the diagnosis of miliary TB. Sputum smear and acid fast staining, histopathological findings in the form of granuloma formation in liver, lung, pleural memberane and bone marrow are helpful diagnostic methods[9].Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a rapid and conclusive diagnosis of miliary TB. PCR detects all Mycobacterium strains with great sensitivity and specificity. The most common clinical presentations include fever, anorexia, weight loss, cough, sputum,and chills. In some cases, the disease presents as fever for unknown reasons[8]. Delays in diagnosing tuberculous meningitis and miliary TB can result in serious complications include hydrocephalus,cranial nerve involvement, convulsions, and death[8,10]. In order to clarify important clinical presentations, useful diagnostic methods,early diagnosis and prevention of severe disease consequences in the patients suspicious for meningitis and miliary tuberculosis,the present review collected the published data on tuberculous meningitis and miliary TB in Iran from 2000 to 2021.

2. Epidemiological status

The prevalence of TB varies across Iran, it is particularly high in the provinces of Sistan and Baluchestan, South Khorasan,Mazandaran, Kurdistan, and Kermanshah, as well as in the southern areas[11-13]. In Iran, the majority of TB cases were reported in Sistan and Baluchestan in the south east areas[11]. Furthermore,EPTB affects 23% of all TB patients in Zahedan, with 6.9% of them having tuberculous meningitis. According to a recent study,meningeal TB accounts for 5.6% of all EPTB cases in Mashhad[13].The annual incidence of EPTB in the Sistan and Baluchestan region was 70 per 100 000 people[11]. Brain involvement in the forms of meningitis, tuberculoma, and TB arachnoiditis were observed in 10%-15% of EPTB cases[14]. Sali et al. indicated that 15% of all TB cases reported from Iran were extrapulmonary, of which 5%-15% were CNS TB[12]. EPTB accounted for 31% of all TB patients in a research undertaken by Sharifi et al. in Zahedan, with 0.3%-22% of those cases being meningeal TB[11]. In a study by Pourmohammad et al., tuberculous meningitis accounted for 20% of all EPTB and 1% of all TB cases[15]. Tuberculous meningitis accounted for 10%-20% of EPTB cases, according to Birang et al[5]. The disparity in EPTB prevalence between studies could be attributable to the methods employed to diagnose the disease. For example, a preference for invasive diagnostic procedures like biopsy and histology over noninvasive approaches might lead to discrepancies in prevalence rates being reported. In the diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis, PCR has been employed as a specific technique[16,17]. In Iran, the mean age of patients with tuberculous meningitis was (41±22.4) years, with a male preponderance (near to 70% of all cases)[1,11]. Radmanesh et al. found that patients' ranged from 18 to 83 years old, with 60% of them being male[18]. The mean age of patients in another study conducted by Moghtaderi et al. was (41.12±22.3) years, with 58% of patients being male[17]. Sali et al. found that the mean age was 66 years[12]. Young or middle-aged men are more likely to have tuberculous meningitis[19]. Meningeal TB is also more common among infants and preschool children. Various studies have found that the prevalence of this condition in youngsters ranges from 3% to 22%[11,20,21].

In countries where tuberculosis is endemic, incidence of meningeal tuberculosis and its related morbidity and/or mortality are highest in young people, but in developed countries, incidence is higher in older people. Immune system deficiency due to aging is a major factor in increasing the incidence of tuberculosis in the elderly.Studies in Iran show that the incidence of tuberculosis decreases slightly after the age of 40 years[22-27].

The disease is already endemic in Iran and therefore there has been contact with microorganisms since childhood and even infant.Children and infant may have nonspecific symptoms such as fever without pulmonary symptoms. For this reason, the diagnosis can be made after the onset of complications, which is sometimes irreversible. In a society where the disease is endemic, immune compromised young people (HIV infection, malignancy or organ transplantation) can also develop the disease through contact with infected people. Delay in diagnosis and occurrence of complications is also possible in this group of patients[28].

Tuberculous meningitis is responsible for 20%-60% of TB-related deaths in children[29]. Tuberculous meningitis affects 31 out of 100 000 babies and 0.7 out of 100 000 children aged 10 to 14 years old. The Bacillus Chalmette-Guerin vaccination protects newborns against tuberculous meningitis by 64%[21]. Meningeal TB in children is frequently misdiagnosed, leading to late and advanced stages[20,21,29]. In the study conducted by Haji et al., most tuberculous meningitis cases in children were reported in the age range from 6 months to 4 years. In that study, the incidence of the disease was 31.5 per 100 000 in the age range from 6 months to 4 years and 0.7 per 100 000 in older children (10-14 years)[30].

CNS TB accounted for 6% of EPTB patients in a study by Afrough et al., and the majority of cases were between ages of 6 months and 4 years[31]. Children’s CNS TB contributes for 20%-45% of all TB cases[31]. Sharifi et al. found that 33% of children with tuberculous meningitis were under the age of 10 years old, with 58% of them being male[11]. Extrapulmonary manifestations were found in 25%-35% of all TB cases in a research conducted by Velayati et al. In a separate research of 1 099 HIV-positive TB patients, 38% of the patients had tuberculous meningitis[2]. Co-infection with TB and HIV makes it difficult to diagnose and delay in treatment of tuberculous meningitis in a timely manner[32,33].

Between 2000 and 2021, 50 cases of miliary TB were documented in investigations, with a mean age of 55 years and a male predominance (60%)[8,34-36]. Mycobacterium bacilli can escape from the primary focus in the lungs and spread via blood circulation to other organs in the body, causing miliary TB in immunocompromised patients (e.g., HIV-positive people),the elderly and newborns, kidney failure, pregnancy in second trimester, liver cirrhosis organ transplant or patients on long term corticosteroid regimens and chemotherapy[8,28,34,36-38].

3. Clinical manifestations

In CNS TB, the disease begins with the progress of small tuberculous foci (rich foci) in the brain, spinal cord, or meninges.The main factors for determining the type of CNS tuberculosis are the location of these foci and the capacity to control them. CNS tuberculosis occurs mainly as tuberculous meningitis and less commonly as tubercular encephalitis, intracranial tuberculosis,or a tuberculous brain abscess[2]. The prevalence of the CNS tuberculosis system will vary depending on the overall prevalence of tuberculosis. In countries where tuberculosis is prevalent,tuberculosis is the most common cause of CNS masses. In immunocompetent patients in Iran, CNS TB accounts for 1%-2% of total TB and 8% of EPTB cases. When the subependymal tubercle ruptures into the arachnoid space, tuberculous meningitis is obligatory, and brain involvement is often more evident towards the base of the brain[30,38]. It creates a gelatinous mass that extends to the pons and optic nerves in cases with severe involvement[39].As the disease progress and fibrosis develops, the cranial nerves become compressed. Aneurysm formation, in situ thrombosis, and focal infarction are created because of localized vasculitis of the arteries and veins. Subarachnoid obstruction might result in CSF with excessive amounts of protein in some circumstances[39,40].Unusual types of spinal TB, such as radiculomyelitis, spinal arachnoiditis, tuberculoma, and syringomyelia, have been documented in locations where TB is prevalent[41].

The Bacillus can live in the foci adjacent to the subarachnoid space for many years. Bacilli can escape and enter the subarachnoid space as a result of trauma or immune system defects in such circumstances[2,31]. Hypersensitivity to Mycobacterium antigens causes pathological alterations in the CNS[6]. Clinical symptoms manifest themselves in two stages: fever, headaches, weight loss, and anorexia or gastrointestinal discomfort are common in early stage; while the symptoms of the delayed phase are more specific, such as loss of consciousness and cranial nerves branches involvement[42,43]. The most prevalent symptoms of tuberculous meningitis in Iranian researches were fever and anorexia, headache and stiff neck (90%), decreased level of consciousness and vomiting(80%), seizure (50%), crialnerve palsy (30%-50%), and elevated intracranial pressure (40%). The course of TB mningitis is slow,with an aseptic pattern in the early stages. An irreversible and severe neurologic consequence is linked to a delay in diagnosis[44]. The most common complications were hydrocephalus (70%), cranial nerve palsy (50%), and mortality (4%)[1,5-7,12,14,15,45].

Afrough et al. identified three stages in the clinical course of tuberculous meningitis[31]. Fever, agitation, anorexia, headaches,and personality abnormalities characterize the first stage, which lasts around three weeks. Meningitis symptoms, neurological problems,and vomiting are signs and symptoms of the disease in its second stage. Leg paralysis, loss of consciousness, convulsions, coma, and death within two weeks are the ominous consequences of the third stage.

In tuberculous meningitis, Radmanesh et al. identified three stages of clinical presentations[18]. Symptoms of personality disorder,anger, anorexia, and apathy endure one to two weeks in the first stage. In the second stage, symptoms such as increased intracranial pressure, neck stiffness, sleepiness, vomiting, convulsions, and cranial nerve palsy emerge. Although the chances of a cerebral infarction, cerebral edema, or coma are low, they are all frightening possibilities. Both early and late in the clinical course, focal or generalized seizures occur[18].

Aminzadeh et al. found that 95% of individuals with tuberculous meningitis were detected five days after onset of symptoms in a study on 22 patients. In 13.5% and 7% of cases, respectively, the sixth and seventh cranial nerves were involved[44]. Optic nerve involvement was observed in up to 35% of cases in a research by Moghtadari et al[19]. Involvement of the cranial nerves affects up to 23% of people[15]. Fever is a symptom that can be seen in as many as 85.5% of cases. Vomiting, loss of consciousness, anorexia, and seizures are other common symptoms, with rates of 73%, 41%,22%, and 9%, respectively[44]. In each study, the prevalence and order of clinical manifestations are not the same. Neck stiffness and fever were recorded in 88% and 65% of cases, respectively,in a research by Haji et al[16]. Tuberculomas are granulomatous masses that range in size from 2 cm to 8 cm in diameter and are usually single, but they can be numerous in 15% to 24% of cases.The computed tomography (CT) findings are a round or lobulated mass with low or high density with ring-enhancement after radiocontrast injection[46,47]. Tuberculoma of the brainstem is extremely uncommon, accounting for fewer than 5% of all intracranial tuberculoma occurrences[31,47]. Another type of CNS TB is spinal cord involvement. Mohammad-nejad et al. described a case of conus medullaris TB in a 46-year-old man with left leg paresis who had previously been diagnosed with TB 15 years ago[46]. A case of spinal cord TB was also reported by Birang et al. in a 20-year-old male with urine incontinence and progressive lower limb paralysis who responded to surgery and anti-TB chemotherapy[5]. Three patients with tuberculous meningitis developed tuberculoma during therapy, a phenomena ascribed to the activated host’s immune responses, and treatment was recommended to continue[12]. Miliary TB is responsible for 1%-2% of all TB cases and 8% of EPTB cases with normal immunity[8]. The most common clinical signs in investigations on miliary TB in Iran were fever of unknown etiology(95%), lethargy, exhaustion, and anorexia (90%). Symptoms of miliary TB include anemia, weariness, and weakness, particularly in the elderly[6,7]. Adenopathy and hepato-splenomegaly may be present, and the diagnosis is sometimes made after the patient has died[8,36].

4. Diagnoisis

The diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis is based on the combination of clinical signs, laboratory findings, and response to treatment. CSF analysis shows an increase in lymphocytes,highprotein, and low glucose[47]. Since signs and symptoms of tuberculous meningitis are non-specific, paraclinical investigation is necessary for definitive diagnosis. In this regard, different paraclinical methods are used for diagnosis as follows: (1) study on CSF, including biochemistry and changes in glucose, protein, and cell count, (2) preparation of smear and acid fast staining, (3) culture of spinal fluid for M. tuberculosis, (4) nucleic acid amplification test and PCR method, and (5) serology and enzymatic assay (adenosine deaminase assay; ADA). Overall, PCR (70%-80%) and CSF culture (25%) were two main diagnostic methods of tuberculous meningitis in Iran. CSF smear for acid fast bacilli was positive in only 5% of cases[48,49]. CSF ADA levels were elevated in 50% of patients. In 95% of cases, CSF had low glucose levels and a marked monocytosis. Clinical presentation, CSF biochemical change, cell analysis, as well as CSF ADA levels are used for the probable diagnosis and clinical decision for management of tuberculous meningitis[50,51].

Tuberculous meningitis has an aseptic pattern, which is included in the differential diagnosis of viral, carcinomas, fungi, collagen vascular diseases, syphilis, and many other conditions with aseptic meningeal inflammation. Moghtadari et al. proposed four criteria for diagnosing tuberculous meningitis: (1) progression of symptoms within five days, (2) age over 30 years, (3) CSF pleocytosis less than 1 000 cells per micro liter, and (4) CSF lymphocytosis more than 70%[19]. In cases where the presence of M. tuberculosis is confirmed by smear or culture or by PCR, a definite diagnosis has to be considered. In cases where the smear,culture or PCR for M. tuberculosis show negative results and the diagnosis is based on clinical manifestations, radiology, and nonmicrobiological laboratory findings, the diagnosis is considered probable. The least essential criteria for considering the diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis are the following: (1) the presence of TB in another organ outside the lung at the same time, (2) history of TB in the family, (3) typical radiological findings in favor of TB, and (4) appropriate response to anti-TB treatments[44,45]. It should be verified that CNS radiology alone is not a diagnostic method for tuberculous meningitis and therefore is not referred to as a diagnostic method. Tuberculous meningitis can be presented with signs of hydrocephalus (70%-80%), ventricular dilatation(51%), contrast enhanced lesions (38%), and low density lesions suggestive of infarction on CT scan or magnetic resonance imaging in many cases, but all of them are not specific diagnosis findings for tuberculosis. However, in patients with radiographic findings of lung involvement in favor of tuberculosis (miliary pattern,cavity formation or any pneumonic infiltration in an endemic area for tuberculosis), it obligate to consider tuberculosis as a main cause of the central nervous system involvement for symptomatic patients[52,53].

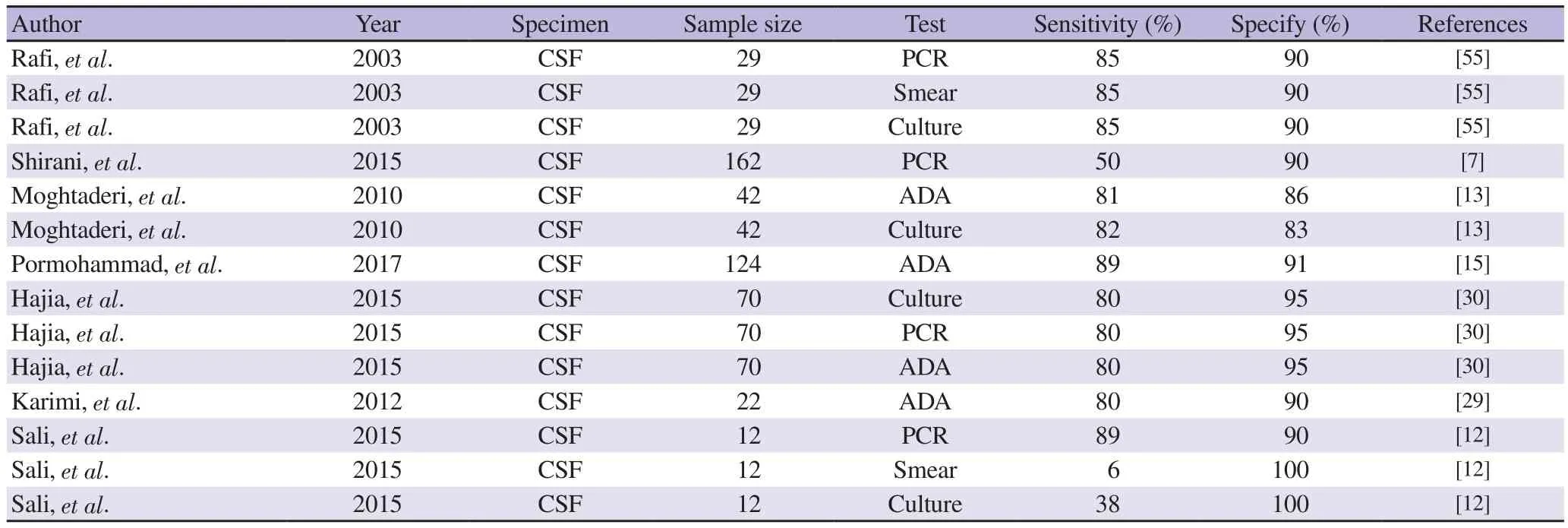

In tuberculous meningitis cases, 40% of the first spinal puncture smear and 78% of the second spinal puncture smear are likely to be positive[54]. Zell Nelson’s staining sensitivity is low, ranging from 10% to 20%[13](Table 1). In the study by Radmanesh et al.,CSF smear was positive in 10%-87%, culture in 7%-87% and PCR in 33%-90% of tuberculous meningitis cases[18]. In the study byRafi et al[55], 29 tuberculous meningitis cases were evaluated by PCR, culture, and smear staining for M. tuberculosis on CSF, with positive rates of 86.2%, 17.2%, and 3.4%, respectively. In 3% of patients, all three methods concomitantly confirmed the existence of tuberculous meningitis. It takes seven to eight weeks to determine M. tuberculosis culture result, while the result of PCR is determined within eight hours[56]. Due to the importance of immediate diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis, culture is time-consuming and it is not a suitable method. The sensitivity of CSF smear staining is low, so it must be repeated several times to get the best results.Therefore, both culture and smear cannot be suitable methods for timely definite diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis[15]. One of the rapid diagnostic methods for tuberculous meningitis is PCR with 25%-85% sensitivity and 95%-100% specificity[12,41](Table 1). In a study by Shirani et al[7], the sensitivity and specificity of PCR were 50% and 90%, respectively[39]. Haji et al. reported the sensitivity and specificity of PCR as 80% and 95%, respectively[30].

Table 1. Used diagnostic methods for studied tuberculous meningitis patients in Iran.

There are four clinical and paraclinical diagnostic criteria for tuberculous meningitis as follows: (1) CSF lymphocytosis >70%,(2) CSF leukocytes count<1 000/mL, (3) age over 30 years,(4) prodromal sign and symptoms length of 5-day duration.Considering all the mentioned criteria, sensitivity of 57%-95% and specificity of 76%-96% in the diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis is obtained[14,15,17]. ADA is a key enzyme that catalyzes adenosine deaminase to inosine, and it plays a role in the proliferation,maturation, and function of lymphoid cells[13,15]. This enzyme is a valuable biochemical marker even in cellular immunodeficiency.ADA is sensitive, but not specific, to the diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis[13]. ADA is further standardized for differentiating tuberculosis in pleural fluid[50].

One of the diagnostic methods for tuberculous meningitis is ADA in tissues and body fluids with accuracy of 50%; and some studies showed a sensitivity and specificity of 58% and 86% for ADA,respectively[13]. ADA levels of more than 15 IU/L differentiate tuberculous meningitis from other causes of meningitis[13](Table 1).ADA levels of 11.4 IU/L have a sensitivity and specificity of 82% and 83% for tuberculous meningitis, respectively. Pourmohammad et al. reported ADA levels of (14.3±3.87) IU/L vs. (9.2±2.14) IU/L in patients with TB versus non-tuberculous meningitis[15]. They also reported mean ADA level of (2.7±1.96) IU/L in patients with noninfectious meningitis (P=0.000 1)[15]. Due to the urgent situation in the diagnosis and treatment of meningitis, it is necessary to use accurate and rapid diagnostic methods. According to accuracy, nondependency on the severity and stage of the disease and also delivery of test results in a short time, nucleic acid amplification tests are advantageous tests[39]. Diagnosis of miliary TB is made by clinical suspicion along with paraclinical investigation. Paraclinical findings include hyponatremia, high levels of erythrocyte sedimentation rate(ESR), leukopenia or leukocytosis, pancytopenia, normochromicnormocytic anemia, thrombocytosis, as well as radiologic changes.Chest X-ray (CXR) is normal in 50% of cases, so high-resolution lung CT scanning is preferred. Contrast-enhanced CT scan and magnetic resonance imaging are more sensitive than plain X-ray in examination of brain. Broncho-Alveaolar samples obtained by bronchoscopic procedure can be useful in diagnosing suspected cases of tuberculosis[57]. Bronchoalveolar lavag has a sensitivity of 100% in the diagnosis of miliary TB[58,59].

CXR has miliary pattern in 70% of cases. Pancytopenia and high ESR levels were observed in 65% and 90%, respectively. Miliary TB was diagnosed with bone marrow biopsy in 80%. Patients with miliary TB have a positive sputum smear for BK in 30% of cases.The PCR test was also positive in 43%-100% of cases. Granulomas were found in bone marrow, liver, and lung tissue. Granuloma is not specific for TB diagnosis except in pleural tuberculosis. Other findings include pancytopenia, agranulocytosis, leukemoid reaction,elevated ESR, and decreased serum albumin[8,36,58]. Alimagham et al. reported an 80-year-old woman from north of Iran with miliary TB. Clinical and paraclinical findings included weight loss of more than 10 kg during five months, anorexia, fatigue, and asthenia.The patient had a history of cardiovascular disease and the ESR was 55 mm/h[36]. Tumor markers including CA 15-3 and CA 19-9 were normal but the level of CA-125 (130 U/mL, normal range:0-33 U/mL) was high. TB was diagnosed by observing granuloma in the bone marrow biopsy specimen[7]. Another case of miliary TB was a 25-year-old woman from Hamedan province suffering from fever and fatigue with CXR changes in favor of miliary TB.Acid-fast staining was positive in spinal fluid examination. The patient also had a high CA-125, which is a surface glycoprotein of ovarian and some other cells that normally have the levels of less than 35 U/MI[6]. The differential diagnosis of miliary TB includes hematological, connective tissue, as well as chronic infectious diseases. The increase in tumor markers (CA-125) was an unusual and interesting event in these cases reports, suggesting gynecological cancers[60].

5. Treatments

The essential and first choice of treatment in all cases of pulmonary and non-pulmonary tuberculosis is 4-drugs protocol for 6 months. It includes a 2-month initial phase with 4-drugs (isoniazid, rifampin,pyrazinamide and ethambutol), and then a 4-month maintenance phase with isoniazid and rifampin. Chronic complications, including persistent inflammation, adhesions, and fibrosis, allow the use of corticosteroids as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of central nervous system tuberculosis. Prednisolone 1 mg/kg or equivalent dose of dexamethasone were used for 6 weeks and then continued to taper with 2 to 4 weeks’ duration. Depending on the therapeutic response, the duration of corticosteroid adjunctive therapy can be managed[35,53,61,62].

Tuberculous meningitis is treated with a protocol similar to other tuberculous cases. However, many researchers believe that the duration of treatment should be increased from 9 to 12 months to reduce the permanent sequels[5,30]. Neurological complications,seizures, impaired consciousness, focal neurological lesions,cranial nerve palsy, and hydrocephalus are the most important complications of tuberculous meningitis[42,46]. Cranial nerve palsy is directly related to poor prognosis. Sali et al. showed that the prognosis of tuberculous meningitis varies based on the time of diagnosis and its stage. With rapid and timely diagnosis, almost all patients respond well to treatment, and delay in diagnosis is associated with high mortality[12].

In areas with high prevalence of tuberculosis such as Iran, where the risk of tuberculous meningitis is also high, it is recommended to suspicious on tuberculous meningitis in any case with fever and situations such as chronic headache, intermittent disturbance of consciousness, and seizures. Due to the difficulty of diagnosis and the multiple differential diagnoses for each patient with neurological signs and symptoms, CSF examination for mycobacterium, ADA and also cell count with differentiation are the essential strategies for diagnostic approach. In the cases of suspicion in favor of pulmonary tuberculosis, the presence of tuberculosis in the family, the presence of CSF with lymphocytosis and high level of ADA, PCR test, smear and culture for tuberculosis should be performed and regardless of a definitive diagnosis, empirical therapy with anti-tuberculosis started as soon as it possible and followed. Patients who have miliary nodules on radiography and have fever, general weakness, anorexia,and weight loss in an endemic area of tuberculosis are more likely to suffer from tuberculosis. High ESR and high level of alkaline phosphatase in such patients, although not specific, increase the likelihood of diagnosis. In case the patient has critical condition, one should not wait for a definitive diagnosis and empirical treatment can be started[53,63-65].

In a study by Bsharat et al.[39], the risk factors for poor prognosis of tuberculous meningitis were age less than two years, loss of consciousness during hospitalization, seizures,spinal fluid protein levels greater than 70 mg/dL, and glucose levels less than 20 mg/dL[39]. Some factors, such as seizures and focal neurologic signs, also prolong hospitalization. Neurologic defects are important both in determining the status in the early stages and also long-term consequence of the disease[66].

The risks of mortality from tuberculous meningitis in 6-month follow-ups were determined by cranial nerve involvement, focal neurologic defects, and paralysis of the limbs with odds ratio of 9.3, 7.1, and 4.2, respectively[41]. Cranial nerve involvement varies from 20% to 35.5% in various studies. Taking into account the optic nerve involvement, the prevalence of all cranial nerve cases reaches up to 37%[5]. Moghtadari et al. reported that cranial nerves palsy with odds ratio of 3.9 is the major risk factor for determining the long-term neurological complications[13]. Stroke and cerebral infarction with prevalence of 29%-45% were among the main factors associated with poor prognosis in tuberculous meningitis[8].

In one study, third ventricle enlargement was seen in 100% of cases with tuberculous meningitis[6]. Hydrocephalus was seen in 80% of children who presented with tuberculous meningitis in stages 2 and 3, as well as in 12% of adults[6]. Hydrocephalus is due to obstruction of basal cisterns. This blockage reduces blood flow to the main arteries of the brain, and eventually causes damage to the parenchyma. Obstructive hydrocephalus leads to increased intracranial pressure and it is associated with poor prognosis.Corticosteroids were suggested for prevention and also treatment in addition to anti-TB administration; but in some cases, surgery and shunt implantation was necessary for fundamental treatment[43].

In a study conducted by Ahmadinejad et al., 80% of patients with tuberculous meningitis developed hydrocephalus. Cranio-peritoneal shunt was implanted in 23% of these patients. Despite anti-TB treatment and corticosteroid administration, early- and long-term mortalities were 22% and 52%, respectively over 10-year followup[6]. Old age, hydrocephalus, and stage Ⅲ disease, positive PCR for M. tuberculosis in spinal fluid were recognized as poor prognostic factors. Approximately 20%-41% of TB deaths in children are due to cerebral TB[30,31]. The mortality rate can reach 30% despite anti-TB treatment[18]. Prednisolone administration (1 mg/kg for 4-6 weeks)increases the chance of recovery[67,68]. Birang et al. considered the combination of anti-TB drug and corticosteroid to be effective in treating patients with tuberculous meningitis; however, some patients needed a surgery[5]. Patients with tuberculous meningitis are classified into three stages: (1) normal level of consciousness, (2)lethargy, and (3) coma[14]. Although spinal involvement during TB is not common, it can be seen in areas with high prevalence of TB.Uncommon forms of spinal TB are seen as radiculomyelitis, spinal arachnoiditis, tuberculoma, and syringomyelia[69,70].

In addition to medical care, spinal cord injuries frequently necessitate surgery[71]. Sali et al. found that meningeal TB has a 19% mortality rate, a 48% morbidity rate, and a 33% recovery rate[12]. Despite therapy, up to 50% of those with tuberculous meningitis die[6]. The death rate for drug-resistant TB reached 100%[6]. Tuberculous meningitis has been linked to a variety of fatality rates, according to several researches (e.g., 27.8%, 64%,and 43.5%). According to Aminzadeh et al., the total fatality rate owing to tuberculous meningitis was 23% (4% in the first week,9% in the second week, and 19% in the third week) of the disease course[44]. According to Ahmadinejad et al., the total fatality rate from tuberculous meningitis was 22%, and if left untreated, it would approach 100%[6]. The need of quick diagnosis and treatment is highlighted in all of these researches. Despite the fact that tuberculous meningitis is a potentially hazardous and fatal disease,initiating therapy before neurological complications develop can greatly minimize morbidity and death. Miliary TB is likewise treated with four medications, according to WHO guidelines, but the treatment course should run up to nine months[6,7,30].

6. Conclusions

According to the findings of this review study, any patient displaying neurological symptoms (e.g., headache, alteration of consciousness, fever, and vomiting) in areas where TB is widespread,such as Iran, must be evaluated for tuberculous meningitis. Miliary TB should be considered in any patient who has a persistent fever and bone marrow involvement. In such circumstances, conclusive diagnosis should be considered by doing specific tests such as PCR for TB and histopathological investigation, and if this is not possible, diagnosis should be made on the basis of clinical signs,epidemiological evidences, CSF biochemical measures, ADA assay, and cell analysis. Treatment should be initiated as soon as feasible if symptoms are consistent with tuberculous meningitis or miliary TB. Given the high prevalence of EPTB cases in Iran and their catastrophic consequences, researchers are encouraged to do additional researches to better understand EPTB preventions and control measures among Iranians.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank all the people who helped in conducting the current study.

Funding

The authors received no extramural funding for the study.

Authors’ contributions

AE conceived the study and AE, SGM, ASP and AB performed the literature search and drafted the manuscript. SGM, ASP, EA and AB revised the manuscript. AE supervised the manuscript. All authors contributed significantly to the manuscript and approved the submitted version.

杂志排行

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine的其它文章

- Surveillance system-based physician reporting of pneumonia of unknown etiology in China: A cross-sectional study

- Outcome of patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia treated with high-dose corticosteroid pulse therapy: A retrospective study

- SARS-CoV-2 infection rates after different vaccination schemes: An online survey in Turkey

- Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage complicating dengue haemorrhagic fever in a 15-yearold boy: A case report

- Membranous nephropathy associated with tuberculosis-a case report

- A hypothetical mechanism whereby malaria infection protects against COVID-19