Prevalence of depression and anxiety among children with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis

2022-03-11ezaAkbarizadehMMaahjiindNaderifarFereshtehGhaljaei

eza Akbarizadeh · MMaahjiind r Naderi far · Fereshteh Ghaljaei

Abstract Background Evaluation of psychiatric disorders in children is essential in timely treatment. Despite individual studies, there is no information on the exact status of psychiatric disorders in children. The present study was conducted to determine the prevalence of depression among children with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Keywords Anxiety · Depression · Diabetes · Meta-analysis · Pediatrics

Introduction

Diabetes is one of the major public health challenges. It is one of the top ten causes of death in the world. According to the latest global burden of disease study in 2020, more than 476 million people of different ages in the world have diabetes. This number is predicted to reach more than 700 million people by 2045 [ 1]. The prevalence of diabetes in children is increasing day-by-day, and there are more than one million children with diabetes [ 2 ]. The most common type of diabetes in children is type 1 diabetes, and its prevalence is 25 per 100,000 people in the United States [ 3]. The prevalence of type 2 diabetes is also increasing in recent years due to lifestyle changes and an increase in obesity and cardiovascular risk factors in adolescents. The overall prevalence of diabetes in children is 5300 per 100,000 population [ 4].

Psychological disorders such as depression [ 5], anxiety[ 6], and stress [ 7] in children affect not just a family but also the society [ 8]. Concerning the individual dimension,depression leads to reduced therapeutic adherence [ 9], sadness [ 10], reduced physical activity [ 11], failed treatment,and ultimately a reduction in quality of life and increase in mortality rate among children [ 12]. Psychological disorders, in addition to the individual, impose a lot of care burden on families and can, in the long term, increase other psychological disorders in the caregivers concerned [ 13].If one were to consider the complex and direct relationship between depression, anxiety, and stress on one hand and treatment outcomes in children with type 1 and type 2 diabetes on the other, it must be noted that international guidelines always emphasize regular and timely screening of patients for psychological problems [ 14, 15]. Previous evidence can help health policymakers prioritize screening, identify more high-risk areas, and determine the severity of any psychological disorder [ 16, 17]. The previous meta-analysis by Buchberger et al. shows that the prevalence of depression was 30% among children with type 1 diabetes. However,the present study took into account only children with type 1 diabetes and not children with type 2 diabetes [ 18].

The systematic review and meta-analysis method is now used to better summarize the results of various studies. To the best of the knowledge of the researchers of this study,despite several individual studies, no comprehensive study has been conducted on the prevalence of depression in children with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Determining the exact prevalence of depression, and anxiety can help policymakers prioritize and better plan for their prevention. The present study, thus, aimed to investigate the prevalence of depression and anxiety in children with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Methods

Registration and eligibility criteria

This systematic review and meta-analysis study was performed using Cochrane book [ 19], and the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses(PRISMA) statement was used for reporting [ 20]. The study protocol is registered in PROSPERO (CRD42021231491).Cross-sectional, cohort, and randomized controlled trials(RCT) studies performed concerning children with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, aged less than 20 years, published in peer-reviewed journals in English, were included in the present study. In selected studies, depression and anxiety were assessed using standard instruments. Reviews, case reports, letter-to-editor studies, and original studies with a sample size of fewer than 25 participants and/or involving children over the age of 20 years were excluded. In interventional studies (RCTs), we extracted and used only the baseline data.

Search strategy

Three databases, viz., Web of Science, Scopus, and Pub-Med were searched for publications belonging to the period between January 1, 2000 and December 15, 2020. Boolean operators (AND, OR, and NOT), Medical Subject Headings(MeSH), truncation “*” and related text words were used for the search within the titles and abstracts, using the following keywords: anxiety, depression, and diabetes (Supplementary Table 1).

Study selection and data extraction

After conducting the search for studies, the studies were selected separately by two researchers (MRA, FG) in Endnote. Any disagreement between the researchers was resolved through discussion. The title, abstract, and full text of the articles were reviewed according to the inclusion criteria after removing the duplicate articles. Extracted data items included: (1) general information: author, year,country, region based on the World Health Organization’s(WHO’s) guidelines; (2) economic status: countries classified based as per the World Bank’s income levels (high income, low and middle income, low income, lower middle income, middle income, and upper middle income, source:https:// data. world bank. org/ count ry); (3) study characteristics: design, time of data collection, questioner name, and number of items; (4) participants characteristics: number of patients, age, gender (female/male), duration of diabetes, and main outcome (depression/anxiety).

Quality assessment

To evaluate the methodological quality of the studies, two different instruments were used based on the types of the studies being reviewed. To evaluate the quality of descriptive studies, Hoy et al.’s instrument was used, which is a 10-item instrument, and it evaluated the studies in terms of external and internal validity [ 21]. It assesses the quality in two dimensions: external validity (items 1-4 assess target population, sampling frame, sampling method, and minimal non-response bias) and internal validity (items 5-9 assess data collection method, case definition, study instrument,and mode of data collection). The Jadad instrument was also used to evaluate clinical trials [ 22]. The Jadad scale score ranges from 1 to 5; a higher score indicates better RCT quality. If a study had a modified Jadad score > 4 points, it was considered to be of high quality; if the score was 3-4 points,it was of moderate quality, and if the score was < 3 points,it was low quality.

Data analysis

All the eligible studies were included in the synthesis after a systematic review. We conducted meta-analysis based-on prevalence and mean score, as appropriate. The data and pooled effect size were presented using the forest plot and tables [ 23]. The heterogeneity of the preliminary studies was evaluated byI

2 statistic [ 24]. Sub-group analysis was performed for assessment tool, sex, WHO regain, and economic status. Also, we meta-analyzed and obtain pooled prevalence of depression based-on mild and moderate-to-severe depression severity. The meta-analysis was conducted basedon random-effects model. The univariate meta-regression analyses conducted for prevalence of depression and anxiety prevalence. Meta-analysis was performed using STATA 14(StataCorp, Texas, USA).Results

Studies demographic characteristics

Study selection

After searching in 3 databases, a total of 5741 articles were found and duplicate cases were removed. A total of 3542 articles were first examined in terms, first, of their titles and then their abstracts based on the inclusion criteria, and the irrelevant articles were removed. A total of 152 related articles entered the next stage, and their full-text was reviewed.A total of 109 articles entered the final meta-analysis stage,and the following 43 articles were excluded: narrative review(18), qualitative (3), non-English (9), and no full text (13)(Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

The 109 studies that had been carried out involved 52,493 children with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, and they were carried out over a 20-year period. Most studies were crosssectional (n

= 98). Most of these studies involved children with type 1 diabetes (n

= 105). By continent, most of these studies had been conducted in the Americas (n

= 64) and Europe (n

= 21), and most of these studies were conducted in countries with high-economic status (n

= 86). Country-wise,most studies were conducted in the United States (n

= 60),Turkey (n

= 8), and Australia (n

= 6). In most of the studies,the data were collected prospectively (n

= 107). The most common questionnaire used in most studies was children’s depression inventory (CDI,n

= 44). The mean history of diabetes duration in children was 5.1 years. The mean ± standard deviation of children’s age was 14.3 ± 2.01 years. In 109 studies in which the participants’ sex was specified, out of a total of 31,728, 16,753 were girls and 14,975 were boys.All included studies had a low risk of bias (Supplementary Tables 2, 3, 4).

Fig. 1 Study selection process

Results

Prevalence of depression and anxiety among children with type 1 diabetes

Of the included studies, 105 studies covered children with type 1 diabetes. Depression and anxiety were assessed in 96 and 32 studies, respectively.

Depression

The prevalence of depression was assessed in 66 studies and reported to be between 1.9% and 81.9%. This study found that the pooled prevalence of overall depression in 21,928 patients was 22.2% [95% confidence interval (CI) 19.2-25.2;I

2 = 97.6%). The prevalence in this study was assessed based on 11 different tools. Most studies used the CDI, (n

= 34),center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CESD,n

= 11), and patient health questionnaire (PHQ,n

= 8)tools. The overall pooled prevalence of depression based on CDI was 18.3% (95% CI 14.3-22.4;I

2 = 95.4%) and lower than pooled prevalence based on CES-D (31.8%) and PHQ(35.9%) (Fig. 2). Of 66 studies, 50, 7, and 9 studies were conducted in high, upper-middle, and lower-middle-income countries, respectively. The pooled prevalence of depression in lower-middle-income countries was 29.3% (95% CI 18.6-40.0) and, thus, higher than in high income countries[22.1% (95% CI 18.6-25.7)] and upper-middle-income countries [14.0 (95% CI 11.8-16.3)] (Fig. 3). Of the 66 studies, 38, 11, 9, and 5 studies were conducted in the Americas, Europe, EMRO, and the Western Pacific region of the WHO, respectively. The pooled prevalence of depression in Europe was 12.1% (95% CI 8.5-15.8), and in the Americas,it was 19.3% (95% CI 17.3-21.3), which was lower than in EMRO [42.7% (95% CI 22.3-63.1)] and the Western Pacific region [33.4% (95% CI 18.7-48.1)]. The pooled prevalence of depression was 13.1% (95% CI 8.5-17.7) for the South-East Asia region and 6.7% (95% CI 2.3-17.9) for the African region based on two and one studies, respectively. The prevalence of depression by sex was reported in 11 studies(out of 66 studies). The sub-group analysis based on sex showed the prevalence of depression in females to be higher than in males in the majority of studies. Accordingly, the pooled prevalence in 1822 males and in 1840 females was 19.7% (95% CI 14.6-24.9;I

2 = 81.0%) and 29.7% (95% CI 22.2-37.2;I

2 = 90.0%), respectively. The pooled odds ratio of overall depression for sex was 1.47 (95% CI 1.24-1.74;I

2 = 6.4%). So, the odds of depression in females were 1.5 times higher than in males (Supplementary Table 5).Of the 66 studies, only 8 studies reported depression in the severity subgroup. The pooled prevalence of overall depression in 6044 patients was 31.1% (95% CI 20.4-41.9;I

2 = 98.8%), and the pooled prevalence of mild depression was 20.2% (95% CI 14.0-26.3;I

2 = 97.4%) and moderate-tosevere depression was 9.2% (95% CI 6.8-11.6;I

2 = 88.2%).The depression mean score reported in 52 studies based on 8 tools. Although of them, the CDI (in 32 studies), CES-D(in 7 studies), PHQ (in 7 studies), and patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (in 2 studies) were used in more than one study. The tools of depression anxiety stress scale, depression self-rating scale, Hopkins symptoms checklist and short mood and feeling questionnaire were used in only one study. The pooled depression mean score was 9.0 (95% CI 7.5-10.5) based on the CDI in 4652 participants, 12.9 (95% CI 10.2-15.6) based on the CES-D in 1087 participants and 6.8 (95% CI 5.5-8.1) based on the PHQ in 1818 participants.

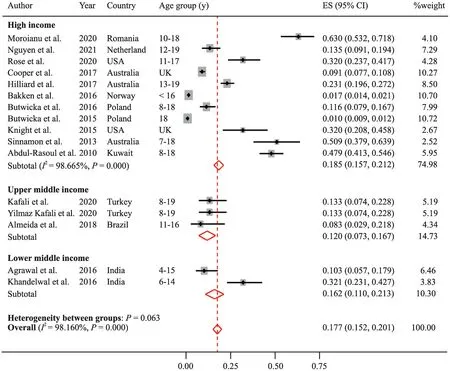

Anxiety

The overall prevalence of anxiety was assessed in 16 studies and reported to be between 1.0% and 63.0%. The pooled prevalence of overall anxiety in 25,095 patients was 17.7%(95% CI 15.2-20.1;I

2 = 98.1%). Of 16 studies, 11, 3, and 2 studies were conducted in high income, upper-middle income, and lower-middle-income countries, respectively.The pooled prevalence of anxiety in high income countries was 18.0% (95% CI 16.7-21.2), and as such, it was higher than that in the lower-middle-income countries [16.2%(95% CI 11.0-21.3)] and upper-middle-income countries[12.0 (95% CI 7.3-16.7)] (Fig. 4). Of 16 studies, 6, 3, 3,and 2 studies were conducted in the Europe, Americas, the Western Pacific region, and the South-East Asia region of the WHO, respectively. The pooled prevalence of anxiety in Europe was 8.6% (95% CI 6.3-10.8) and lower than that in the South-East Asia region [16.2% (95% CI 11.0-21.3)],Americas [23.8% (95% CI 7.3-40.3)] and the Western Pacific region [25.8% (95% CI 11.1-40.5)]. Also, the prevalence of anxiety was 47.9% (95% CI 41.3-54.6) in the EMRO region as per one study.Meta-regression

The results of univariate meta-regression analyses,showed publication year of study variable [Beta = 0.65(95% CI − 0.19 to 1.5),P

= 0.128], mean age [Beta = 1.2(95% CI − 0.65 to − 3.0),P

= 0.204) and hemoglobin A1C(HbA1c) [Beta = 2.9 (95% CI − 2.3 to − 8.0),P

= 0.263]not significantly contributed to heterogeneity of depression prevalence (Supplementary Fig. 1). Also, the results of univariate meta-regression analyses, showed the publication year of study variable [Beta = − 1.4 (95% CI −5.0 to − 2.2),P

= 0.418], mean age [Beta = 2.3 (95% CI − 0.83 to − 5.5),P

= 0.135] not significantly contributed to heterogeneity of anxiety prevalence, but HbA1c was marginally significant[Beta = 8.7 (95% CI − 0.02 to − 17.4),P

= 0.050].

Fig. 2 Forest plot and meta-analysis of depression prevalence in type 1 diabetic children in the world by assessment tool. PHQ patient health questionnaire, PROMIS patient-reported outcomes measurement information system, CES-D center for epidemiologic studies depression scale, CDI children’s depression inventory, BDI beck depression inventory, DAWBA development and wellbeing assessment, CPMS childhood psychopathological measurement schedule, ICD international classification of disease, DSM Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSRS depression self-rating scale, PH-PANAS-C physiological hyperarousal-positive and negative affect scale for children, ES effect size, CI confidence interval, UK unknown

Fig. 3 Forest plot and meta-analysis of depression prevalence in type 1 diabetic children in the world by World Health Organization region. ES effect size, CI confidence interval, UK unknown

Fig. 4 Forest plot and meta-analysis of anxiety prevalence in type 1 diabetic children in the world by economic status. ES effect size, CI confidence interval, UK unknown

Prevalence of depression among children with type 2 diabetes

Of the included studies, ten studies involved children with type 2 diabetes. All of these studies assessed depression, and none of these studies considered anxiety. All of these studies were conducted in the Americas region of the WHO (nine in the USA and one in Canada). The prevalence of depression was assessed in nine studies and reported between 13.7%and 48.3%. The pooled prevalence of overall depression in 3323 patients was 22.7% (95% CI 17.3-28.0;I

2 = 93.1%)(Fig. 5). The prevalence of depression by sex was reported in four studies. One of these studies was conducted only on women. A sub-group analysis based on sex showed the pooled prevalence in 492 males and 965 females to be 21.8% (95% CI 8.5-35.2;I

2 = 92.3%) and 31.2% (95% CI 18.0-44.5;I

2 = 95.1%), respectively.The mean score of depression in children with type 2 diabetes was reported in three studies based on three tools that these studies used. The score was 3.2 (95% CI 2.8-3.6) based on the PHQ by Glick et al. [ 25], 14.1 (95% CI 10.6-17.6)based on the CES-DC by Cullum et al. [ 26], and 7.1 (95%CI 6.6-7.6) based on the beck depression inventory and CDI by Weinstock et al. [ 27].

Discussion

Fig. 5 Forest plot and meta-analysis of depression prevalence in type 2 diabetic children. ES effect size, CI confidence interval

The results indicate that the prevalence of depression and anxiety among children with type 1 diabetes were 22.2% and 17.7%, respectively. The prevalence of depression among children with type 2 diabetes was 22.7%. Today, with the increasing prevalence of diabetes in children, the prevalence of psychological disorders in them is also increasing. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the prevalence of depression and anxiety in children with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. A total of 109 studies that studied 52,802 children with diabetes entered the final stage of the review process adopted for the present study. As in the past studies, CDI was the most commonly used instrument for this study as well [ 18]. Other instruments were CES-D and PHQ. The difference in the prevalence of depression in the three instruments can be due to the following reasons. First, CDI is a child-specific tool, but CES-D and PHQ are general tools for assessing depression. Second, each of the tools examines different dimensions of depression with a different number of items, which could mean that the evaluation of different symptoms in children was based on different tools/items,resulting in differences in the prevalence rates of depression. Another reason could be the number of studies and the sample size of studies based on the type of instrument used [ 28, 29].

The mean history of diabetes duration was 5.1 years,which was unlike the previous study, which was more than 7 years [ 18]. Concerning type 1 diabetes, the results of the present study showed that the prevalence of depression was 22.2%. This is inconsistent with the previous meta-analysis,in which Buchberger et al. showed that the prevalence of depression was 30.04% [ 18]. The reason for this difference could be due to methodological variations (number of studies, number of participants, etc.) and differences in the instruments used to assess depression [ 18]. Inconsistent with the present study, a study indicated that the prevalence of depression in adults with type 1 diabetes was 12%, indicating that depression prevalence is higher in children than in adults [ 30]. Age has always been considered to be one of the risk factors for depression in people with diabetes. Although the exact relationship between age and depression in patients with diabetes remains complex, studies show that older people with diabetes are less likely to experience depression.Community-based studies also show that young people are more prone to depression after diabetes [ 31, 32].

Also, in contrast with the present study, the global prevalence of depression in healthy children is said to be 2.6%,which is less than what was found by the present study. The higher incidence of depression in children with type 1 diabetes is said to be due to the long-term psychological effects of the disease [ 33]. Long-term psychological complications can be due to the effects of physiological and emotional stress on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic nervous system, which ultimately leads to depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders [ 34- 36]. Other evidence suggests that depression is twice as common in children with diabetes as in healthy children [ 37].The results of past meta-analysis studies suggest that depression prevalence was higher among children with other chronic diseases such as stroke (30%) [ 38], breast cancer (32.2%) [ 39], and hypertension (26.8%) [ 40] when compared with children having type 1 diabetes. The reason for this difference could be the specific differences in the pathology of diabetes and other chronic diseases, the severity and duration of the disease,and the differences in the symptoms that appear in patients with different chronic diseases.

The mean depression score was nine among children with type 1 diabetes based on the CDI scale, which was almost equal to the average depression score of 9.1 obtained in Buchberger et al.’s study. This could be due to the same type of diabetes (type 1) being studied, similar studies being included, and the same instruments being used [ 18].

Present study has also shown that the prevalence of depression in children with diabetes living in lower and upper-middle-income countries is higher than that in those living in high-income countries. The higher prevalence of depression in less developed countries can be attributed to the lack of awareness programs about the psychological consequences of diabetes, late diagnosis of the mental disorders associated with diabetes, lack of screening programs for psychological disorders, and less focus on treating mental health problems in patients with diabetes [ 41, 42].

The prevalence of anxiety was 17.7% in children with type 1 diabetes. To the best of the knowledge of the researchers of this study, there has been no similar meta-analysis study about the prevalence of anxiety in children with type 1 diabetes. However, previous cohort studies have shown that the anxiety prevalence was 37% [ 41]. Unlike in the case of children, the results of a systematic review study showed that the prevalence of anxiety in adults with diabetes was 14%,suggesting that adults experienced less anxiety than children[ 42]. However the differences in these findings could be due to methodological differences such as the number of studies entered and the type of tools used to measure anxiety in the two studies as well as the differences in the anxiety response mechanisms in children and adults [ 43].

Anxiety control is essential in children with type 1 diabetes because studies show that a direct relationship exists in them between controlling anxiety and improving treatment outcomes, glycemic index control, self-management, and higher quality of life [ 44- 46]. The depression prevalence was also 22.7% in children with type 2 diabetes. With the increasing prevalence of risk factors such as obesity, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in adolescents is also increasing these days. Despite the involvement of complex social,biological, psychological, genetic, and neurological components in this increase, the exact causes of the increase in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in children are still unknown[ 47]. Unlike in children, depression prevalence is 28% in adults having type 2 diabetes [ 48], which is higher than in children, and this finding is consistent with previous studies.These results may be due to the large number of studies conducted on adults as well as the paucity of information about depression in type 2 diabetes [ 14, 48, 49]. Another reason could be the difference in the instruments used, the duration of patients’ follow-up, the data collection methods used, and the demographic characteristics of the participants in the two studies. The depression prevalence in girls with type 2 diabetes was higher (31.2%), which is consistent with the findings of previous studies on adults [ 48, 50]. According to the evidence showing a direct relationship between anxiety with diabetes and HbA1c factor and considering that it is treatable, it is essential to pay adequate attention to depression [ 51, 52]. Previous evidence has also shown the effect of anxiety on HbA1c [ 16, 53]. Anxiety can disrupt the mechanism of psychological regulation process in brain [ 54]. Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease with both genetic and environmental mechanisms that lead to destruction of insulin producing beta cells. In type 2 diabetes, insulin secretion is inadequate to compensate for insulin resistance usually associated with severe obesity in adolescents [ 55, 56]. In the past, type 1 diabetes was much more common in children than type 2 diabetes; however, with today’s lifestyle changes,increased obesity, and decreasing physical activity, type 2 diabetes is also on the rise among children [ 57].

According to the number of studies included in the present study for each type of diabetes, the results showed that most of these studies were performed on children with type 1 diabetes, and there were few studies on depression in children with type 2 diabetes, but more importantly studies on anxiety in children were not found. This indicates that further studies are needed.

The most important limitation of the present study was the inclusion of descriptive studies having high heterogeneity. So, it is difficult to generalize the results, and caution must be exercised while interpreting the results.Attempts were made to contact authors of studies where the data made available was found to be limited. Despite the above-mentioned limitations, to the best of the knowledge of the researchers of this study, this is the first review study that examined the three dimensions of anxiety and depression, in children with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. It also investigated the prevalence of depression based on the income levels of different countries and regions.

In conclusion, considering the high prevalence of psychological disorders in children with diabetes, the results of the present study highlight the importance of regular screening for depression and anxiety in children with diabetes. Large-scale prospective studies and early diagnosis of depression in the milder stages can avoid the additional costs associated with the management of depression in the more acute stages.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at https:// doi. org/ 10. 1007/ s12519- 021- 00485-2.Author contributions

AM contributed to conceptualization, reviewing and editing. NM and GF contributed to original draft preparation,reviewing and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.Funding

None.Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.Declarations

Ethical approval

Not needed for the meta-analysis.Conflict of interest

No financial or non-financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.杂志排行

World Journal of Pediatrics的其它文章

- Risk factors for Clostridioides difficile infection in children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Chest CT features of children infected by B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant of COVID-19

- Evaluation of the Quick Wee method ofinducing faster clean catch urine collection in pre-continent infants: a randomized controlled trial

- Physicians’ perspectives on adverse drug reactions in pediatric routine care: a survey

- Two approaches for newborns with critical congenital heart disease:a comparative study