Sportsfor All

2022-02-25

Money has poured into the Chinese sports and fitness sectors over the last three decades, with participation soaring and facilities expanding like never before. Yet two significant segments of China’s population are yet to be swept along: those with disabilities and those in the countryside.

Though the PRC has enjoyed unprecedented Paralympic glory over the last two decades, many para-athletes reap scant rewards for their success in competition—some even working two jobs to fund their training, or dropping out of sport altogether. Likewise, rural areas have struggled to provide the facilities and organization necessary for villagers to enjoy sports and stay healthy through exercise, with funding falling short, youngsters in low supply, and residents sometimes reluctant to participate.

Could plans to improve the social standing of para-sports and make sports more inclusive for the country’s 2.7 million para-athletes, along with goals to install a basketball court in every village in the country by 2030, finally make a difference to those left behind in China’s sporting revolution?

殘奥会上,残疾人运动员屡创佳绩;乡村里,篮球和瑜伽广受欢迎。但在全民体育、全民健身的风潮中,残疾人体育和乡村体育还缺乏更广泛的关注和支持。万众瞩目的奥运会之外,体育也属于所有人。

Illustration and design by Cai Tao and Fengzheng Yisheng; photographs from VCG

Para-Prejudices

Despite leading the world in sports achievements, China’s para-athletes struggle for recognition and inclusion

Since November of last year, 31-year-old Zang Haorong has been working for his wife’s e-commerce business in the small city of Laixi, Shandong province, packing fruits and other agricultural products to send around the country, “I send out ten vans full of products each day; my hands are sore from sticking on the address tags,” he shared in his “Moments” feed on messaging app WeChat one day.

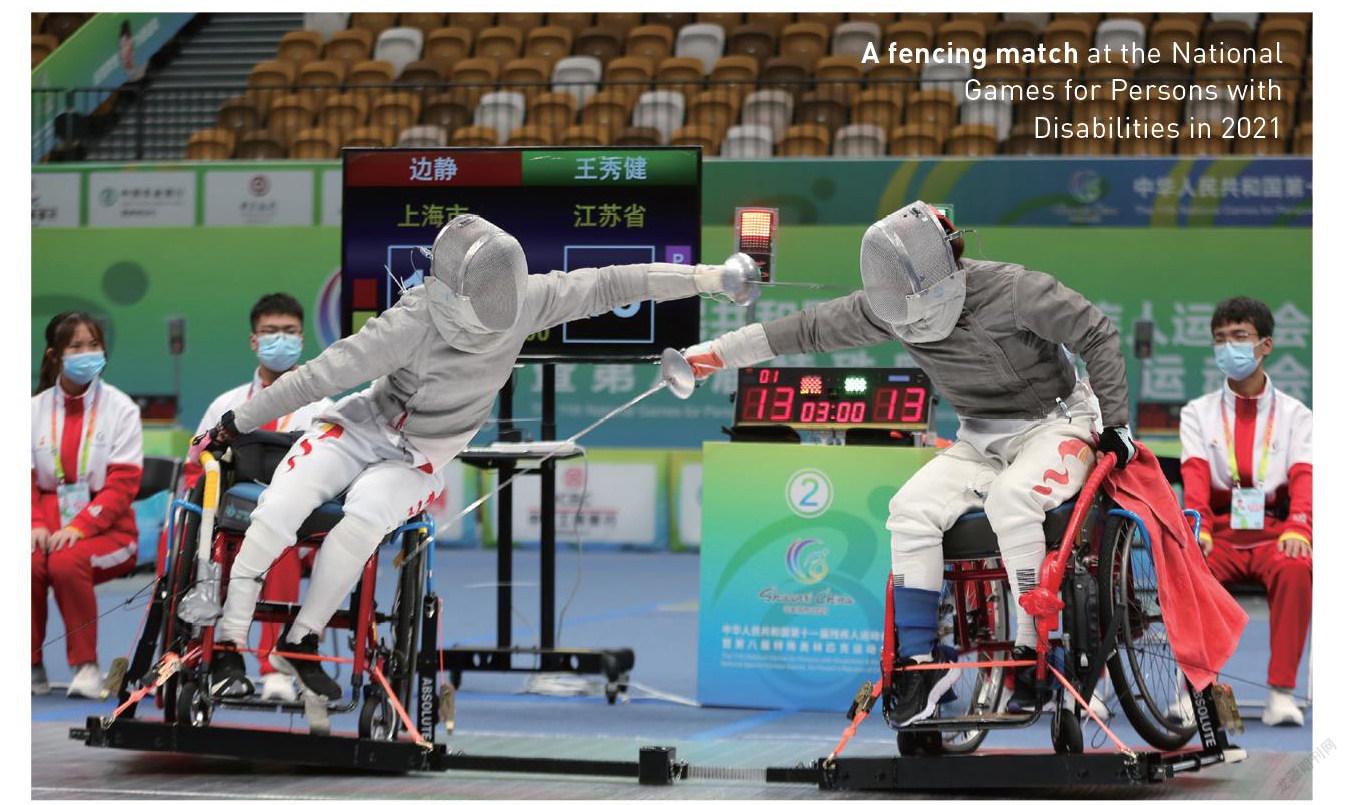

But far from complaining about this life, packing products is actually Zang’s “holiday”: Next spring, Zang, who is visually impaired, will return to the city of Qingdao to resume training in judo to compete in national and provincial games. Just ten days before his November Moments update, he won a silver medal of the men’s 100 kg competition at the 11th National Games for Persons with Disabilities in Xi’an, Shaanxi province, earning a new addition to his collection of over a dozen medals, and a reward of around 200,000 yuan from his local government in Shandong.

Though receiving just a fraction of the coverage of Olympic athletes, Chinese para-athletes’ performances have been nothing short of sensational since the country began participating in international competitions in 1984. It has topped the gold-medal table at every Paralympic Games since 2004, and obtained 96 gold medals at the Tokyo Games in 2021—over twice as many as the second-ranked country, Great Britain, which had 41. One of the gold medalists, 33-year-old swimmer Jia Hongguang, who competed with an arm amputation and won a men’s 100-meter backstroke event, was praised by officials in his hometown of Liaocheng, Shandong, for “winning honor for the city and the country,” and received prize money of 1.36 million yuan from the local government.

Yet as the medals and prize money pile up, China still faces an uphill battle in making parasports truly inclusive for the country’s estimated 2.7 million para-athletes, according to figures from the China Disabled Persons’ Federation (DPF) in 2011. “We have no shortage of Paralympic gold medals, but does society truly respect parasports?” Chen Guoqiang, professor from the Shanghai University of Sport, questioned in an op-ed in The Paper in June 2017, calling for better accommodation of people with disabilities in Chinese society and integration of para-athletes into competitions for able-bodied athletes.

Compared with the Olympic Games, the Paralympic Games has received far less attention. While air rifle athlete Yang Qian got over 530,000 fans on Weibo after she won China’s first gold medal at the Tokyo Olympics on July 24, and more than 3 million “likes” on one of her posts, news about the Tokyo Paralympics and Paralympians rarely got more than a few hundred likes and comments on the microblogging platform. Chinese search engine Baidu returns only 3 million results for the phrase “Tokyo Paralympic Games,” compared to 100 million for “Tokyo Olympic Games.”

China began to develop parasports in the 1980s, with the municipal Party committee and government of Tianjin and the Red Cross Society organizing the country’s first large-scale parasports event in October of 1983: a tournament for 200 visually impaired or amputee athletes from 13 provinces and provincial-level regions. A year later, the country held its first National Games for the Persons with Disabilities (sometimes nicknamed “National Paralympics”). Since then, parasport competitions at national, provincial, and city levels have taken place every two-to-four years.

The government has also created laws and regulations to safeguard rights and access to sports of people with disabilities. The Law on the Protection of Disabled Persons, enacted in 1990, stipulates that the disabled “shall be assisted in access to cultural, sport, and recreational activities.” In 1995, the State of Council, China’s top decision-making body, published the “Guidelines for All-People Fitness Plan” to facilitate sport activities for students at schools for people with visual, hearing, and psychological impairments, as well as fitness activities and competitive tournaments for people with physical and mental impairments.

Zhang Baofeng, a 54-year-old racing medalist at China’s Second National Paralympics in 1987, still remembers his excitement when he heard news of China’s First National Paralympics in 1983, three years after he lost both his arms due to an electric shock and dropped out of school. At that time, he confined himself mostly at home in Zhanghuolang village, Liaocheng, feeling hopeless as a “cripple (残废)”—then a common term for the disabled using the characters for “incomplete (残)” and “uselessness (廢).”

“It made me feel there are platforms for people with disabilities to showcase their abilities too,” Zhang tells TWOC over the phone, recalling the medals, media coverage, and para-athletes’ recognition by the public and government at the time. “It made me hopeful there was a path to a future for people with disabilities, that you’re not useless if you have a disability.”

Similarly, Zang says judo gave him the self-confidence and opportunity to venture out of his comfort zone. He had been born with a condition that caused his eyesight to decline progressively, and is completely unable to see in the dark. Zang learned judo at the age of 15 at the Qingdao School for the Blind, as a training partner of the school’s women’s judo team established in 2005 to honor the upcoming Beijing Olympics.

Though the team was disbanded a couple of years later, and Zang was never able to receive regular training at school, he devised his own strength-training program on parallel bars, horizontal bars, and other apparatuses, as he lacked access to professional judo training facilities. Zang joined a local team in Qingdao in 2009, when the city began recruiting athletes for the 2010 Eighth Provincial Games for Persons with Disabilities, in which he won a gold medal in the men’s 100 kg judo event and qualified to enter the provincial team.

Three years later, he decided to become a full-time athlete. “The main reason was that the local Disabled Persons’ Federation (DPF) offered me a salary and paid social insurance for me [to be an athlete]. As [the DPF and the government] started to pay more attention to parasports…the subsidies and rewards also skyrocketed,” Zang explains.

Unlike able-bodied athletes on state-run teams, para-athletes are not guaranteed a regular salary. Generally, they’re offered free meals and accommodation, and some stipends during the months of training camps before major competitions, with the amount varying between locations. According to shooting athlete Lin Haiyan from Beijing, a gold medalist in a women’s 10-meter air pistol event at the Beijing Paralympic Games in 2008, the stipend used to be just 10 yuan per day at the time, now increased to 100 yuan per day.

Paralympic athletes also receive far less in prize money than their Olympic counterparts. In 1984, long-jump athlete Ping Yali got only 350 yuan for winning one gold and one silver medal in the Paralympic Games in New York, while Olympic 50-meter pistol champion Xu Haifeng received 9,000 yuan for his performance in Los Angeles that same year. Both were China’s first medalists in the Paralympics and Olympics, respectively, though only Xu is remembered in school textbooks.

It wasn’t until the 2008 Beijing Games that the national prize money for Paralympic and Olympic gold medalists both started at 500,000 yuan, according to Lin, though regional sports bodies have no such standards.

These are similar to trends worldwide: In Japan, gold-winning Paralympic athletes typically receive less prize money than their Olympic counterparts. Paralympians in Australia and Canada don’t get cash prizes for winning medals at all, according to Australian broadcaster SBS News, while Olympians do.

Adding to the financial pressure, para-athletes who have to work other jobs to support their training could risk losing their jobs if their employers do not grant them time off to attend the months-long training camps before major tournaments, Lin tells TWOC. Parasport teams, on the whole, report having less funding than teams in able-bodied sports, and often needing to rent and borrow training facilities. Athletes need to cover their own costs if they want extra training beyond what is offered by the state-run teams.

For these reasons, being a “professional” para-athlete like Zang is not an option open to most athletes. Currently, Zang is the only full-time judo athlete on his provincial team of Shandong, a province that has produced a number of relatively high-profile para-athletes. His wife’s e-commerce business takes some pressure off the family, or else he might not have been able to choose a career in sports. “The provincial DPF will cherish you and let you stay in the sport only if you get good results in competitions. It’s kind of ‘survival of the fittest,’” Zang says.

This is one reason why Zang’s former teammate, Luo Wencong, chose to give up his athletic career to pursue a college degree. The 26-year-old from Linyi, Shandong, now a senior at Beijing Union University, tells TWOC he hated working with DPF officials, who “are keen to cash in on the sport, but don’t care much about athletes.” He implies there is corruption when it comes to officials’ decisions about how to distribute winnings and benefits from tournaments, but declines to provide further details on record.

Despite increasing rewards and subsidies, most parasport teams are facing difficulty recruiting young athletes. Lin, the 2008 Paralympic medalist, points out that benefits such as free room and board, stipends, and the (slim) chance to be offered a job or a civil servant’s position after retirement (the latter usually given only to top-performing Paralympians) are not as attractive to young people as in the old days, especially as the government increases social benefits and subsidies to citizens with disabilities.

Zhang, who founded Liaocheng’s first para-swimming team in 2006, three years after his retirement, has noticed the same trend in recent years while recruiting athletes in rural areas. “In the early 2000s, children with disabilities from poor families would choose sports as their path to a better life, so they were able to bear the hardship [of training],” he explains. Now, however, “well-off villagers are unwilling to send their children to practice sports, which is tiring and time-consuming.”

Some parents even think sports are cruel to people with disabilities, while athletes and people with disabilities chafe at the typical media narrative that holds up para-athletes as “inspiring,” when it pays attention to them at all, rather than simply celebrating their achievements.

Luo, the university student and former athlete, hopes one day such stereotypes can disappear. He tells TWOC, “Me practicing judo is nothing special. Everyone has a hobby, and mine is judo.”

– Tan Yunfei(譚云飞)

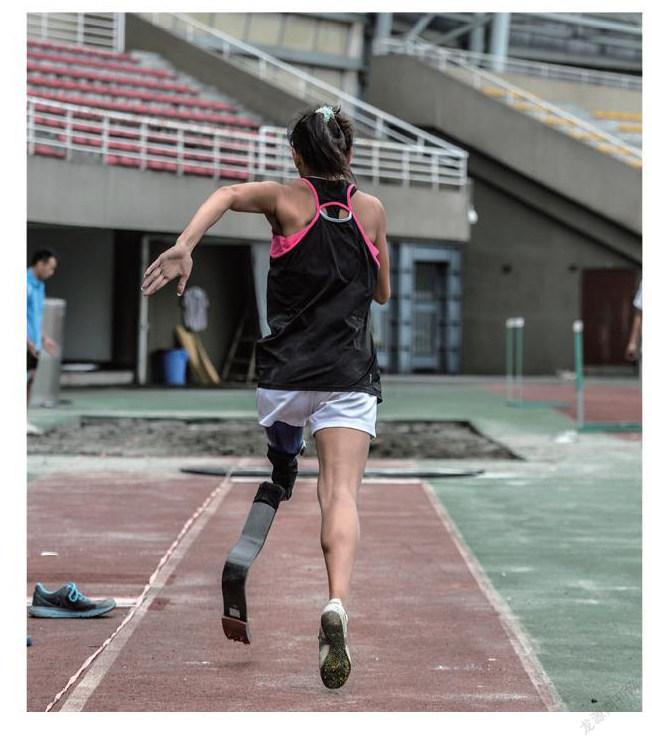

Clockwise from top left: A para-athlete in Chengdu runs with a prosthetic leg; a wheelchair-racing athlete competes at the Guangzhou 2020 Asian Para Games; ice hockey players get changed in the locker room before training

Zhou Xintao, a former member of the national para-snowboarding team, could reach a speed of over 70 km/h

A fencing match at the National Games for Persons with Disabilities in 2021

Taking the Field

Village sports programs try to get all people in China exercising—with mixed results

The village auditorium in Hongxi, Zhejiang province, was packed for the fourth night in a row. While the athlete’s sneakers screeched against the waxed wooden floor, the audience, many of them elderly farmers, tracked the movement of the ball with knitted brows and mouths agape.

At intermissions, a group of middle-aged women in fluffy green dresses marched onto the court, dazzling the audience as they swirled in circles with purple fans raised in their hands. This was Hongxi’s own grassroots cheerleading team, the “Hot Mama Babies.” On that night of November 23, 2018, Hongxi beat Shanghai’s Fumin village with a score of 74 – 73, winning the 11th China Basketball Village Championship by a hair.

“Every time we play, our villagers always shout in unison, ‘Go, Hongxi Village! Go, Hongxi Village!’” Chen Liqun, the village’s party secretary, reminisces fondly as she talks to TWOC over the phone. Organized by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, the China Basketball Village Championship is a series of competitions between village basketball teams from all over the country. It was the fifth time Hongxi hosted had the match. “Activities like this put the hearts of the whole village in the same place,” declares Chen.

In China’s urban areas, the sports industry is booming: According to a study of 18 cities by consulting firm Deloitte between 2019 and 2020, the annual revenue from the gym industry in these cities is now close to the total annual gym revenue of the UK, exceeding 30 billion yuan. Vancouver-based athleisure brand Lululemon doubled its revenue in China during the third quarter of 2020.

In villages like Hongxi, however, sports development isn’t measured by gym memberships and consumer spending on yoga pants. Since the early years of the PRC, China has deployed sports as an instrument to solve social problems beyond mental and physical health, and even now fitness is deeply intertwined with pressing national issues like poverty alleviation, rural depopulation, and economic development.

Besides Hongxi, the remote village of Yugouliang in northwestern Hebei province, about 100 kilometers from China’s Winter Olympic facilities in Chongli, has recently gone viral due to a group of elderly women who can strike yoga poses with apparent ease. In videos on short-video platform Kuaishou, Yugouliang’s yoga grannies, wearing their signature blue head wraps, practice full lotus sits, snap into headstands, and even bind their legs behind their heads in fields, the snow, and on concrete sidewalks. Behind them, there’s often a white wall scrawled with a slogan in big red characters: “Poverty alleviation gathers the wisdom and hearts of the people. Yoga practice brings out the spirit of Yugou.”

For Yugouliang, yoga does not only bring out spirit, but also fame—the village has now been heavily covered by domestic and international media outlets, featured in a film, and anointed “China’s first yoga village” by the General Administration of Sports (GAS).

The village shares the struggles of many rural locations in China: remote, with scarce precipitation and land productivity, suffering from an exodus of young labor, and left with roughly 100 residents, 80 percent of whom are above age 65. The forces of these challenges were evident in the ailing population, when Lu Wenzhen arrived in 2016 to serve as the village’s party secretary.

Since 2012, when the Chinese government made it a priority to eradicate poverty nationwide, Beijing has sent 3 million cadres to impoverished rural areas to establish and carry out targeted poverty alleviation strategies. Impressed by the way locals sit cross legged on their beds for long periods of time, Lu decided that yoga training could help the village become more prosperous. His logic was straightforward: Villagers already seemed to have the flexibility, and if this sport could strengthen their body and spirit, it might also reduce their medical bills.

Stories of sporting villages tick many boxes of China’s development goals. Besides eradicating poverty and caring for its aging population—70 percent of rural elders suffer from chronic disease according to the 2014 China Longitudinal Aging Social Survey, a nationwide survey led by Renmin University—and increasing positive coverage about China in the media, fitness and sports have also become part of the national agenda.

The State Council’s “Healthy China Initiative 2030,” first announced in 2016, set a goal of getting 40 percent of the population exercising “regularly” by 2030, defined as at least 30 minutes of mid-to-high-intensity workouts more than three times a week. It also called for sports facilities in all villages nationwide, which include “at least one standard concrete basketball court and two table tennis stations,” stated Lang Wei, then-head of the Sport for All Department at GAS, at a press conference in 2019.

This is not the first time that sports in rural regions made their way into China’s centralized planning. In a 2011 article, Lu Wenyun, a scholar in physical education at China West Normal University, and Ian Paul Henry of Loughborough University in the UK, comb through Chinese rural sports policies from 1949 to 2008, and group the developments into three stages.

The first began with the establishment of the PRC in 1949 and ends after the Cultural Revolution in 1977, and was marked by the theme of “improving fitness for labor and national defense.” For the growing new nation with a majority rural population, building up a national defense and healthy workforce was a priority. It was during this period that “radio gymnastics” workouts, a system of non-intensive calisthenics, became popularized in schools and state enterprises.

As China’s focus shifted from national defense and class struggle to economic development, Lu and Henry mark 1977 to 2001 as the second stage of rural sports policies, focused on incorporating sports in education and using it to enrich lives and “improve people’s moral well-being.” In 1985, the central government started a rewards system for “advanced sports counties” based on the size of their sports budget, participation, and organizational structures, and it began to hold a national sports competition for farmers every four years starting in 1988.

A dedicated governmental department, the National Sports Federation for Farmers, was established in 1986 to oversee the implementation of sports policy in rural areas and channel funding into rural sports, such as through the 2001 Xuetan Project, which allocated funds raised by the national sports lottery tickets to construction of sports venues and facilities in remote and impoverished areas.

The third period, from 2001 to the Beijing Olympics in 2008, is considered a period of equity and inclusion by Lu and Henry, which saw increased government investment to strengthen sports organization and facilities, especially in poverty-stricken areas, as a way of bridging the urban-rural gap.

Throughout these shifts, sports have been viewed as an instrument that plays various roles beyond just improving physical and mental health. At the grassroots, the role of sports in rural development also varies. Yugouliang, for example, looks to expand poverty alleviation beyond merely skimming medical costs. Capitalizing on its yoga fame, the village has been testing the waters of developing into a tourist destination, or harvesting its newfound social media influencer status to sell locally-grown quinoa or selenium-enriched potatoes.

In some villages, sports are a social adhesive. Hongxi village had been going through some rough patches in the early 2000s, when grudges brewed between residents and the village administration over the government’s handling of land requisitions. According to Chen, it was only during the occasional basketball games against other villages, a local tradition that has waxed and waned since the 1940s, that residents manifested some unity in cheering for Hongxi.

Chen, therefore, saw reviving the village basketball team as a way to occupy the time of villagers who might otherwise be petitioning the local government or fighting among themselves for land rights, as well as to foster closeness between residents and local officials by getting them to play together. For middle-aged women who didn’t play basketball, Chen got them together to form the cheerleading team.

“It was a bit embarrassing at first,” Chen admits. Then in her 40s, and describing herself as “not having a single artistic gene,” she signed herself up for the team going door-to-door to convince other women to join. The Hot Mama Babies now has 26 members with an average age of 43, who are frequently invited to sports matches and talent shows around the country, and even attended the Ronda International Folk Gala in Spain.

The basketball team, a two-time winner in the national China Basketball Village Championship, has also managed to attract some young blood back into the aging village. Chen Jiajie, a 1.98-meter-tall 27-year-old, who trained with the provincial basketball team in Zhejiang since age 15 and was once on track to become a professional athlete, decided to return to Hongxi after he graduated from Zhejiang Normal University in 2017.

“I came back because of my love for basketball and for my hometown,” Chen Jiajie tells TWOC. He now serves as a key player on the village basketball team as well as vice-party secretary of the village, handling on-the-ground affairs from conflict resolution to pandemic control.

For other youngsters, sports are a way out of a village. In the 2020 documentary , a baseball training institute on the outskirts of Beijing gathers teenagers from impoverished backgrounds around the country and trains them to compete internationally. Xu Huijing, the film’s director, writes in a comment on film-rating website Douban, “Baseball has given [these teens] a direction to work hard toward, and opportunities to change their destiny.”

However, promoting sports in rural areas remains a major challenge as physical education is undervalued in China’s exam-based education system, particularly in rural areas where families place more emphasis on standardized testing. In late 2015, UNICEF ran a PE teacher-training workshop in Beijing with FC Barcelona and China’s Ministry of Education, as part of a program aimed at improving physical education in rural schools in China’s underdeveloped western region, and published a report noting that “PE classes always give way to other subjects due to the heavy study load, and it’s difficult for PE teachers to get promoted.”

The report also quotes a Yusufu Maimaitiniyazi, a rural PE teacher from Xinjiang, pointing out the lack of PE facilities in developing regions. “Children in our place, both girls and boys, love soccer…Every night, we spray water on the ground so the earth hardens and children can play soccer the next day.”

According to Lang Wei, 570,000 villages had sports facilities as of 2019, slightly over 50,000 villages away from GAS’s goal of 100 percent coverage. Hongxi village invested 1.8 million yuan into renovating its basketball court in 2013, which is still well-used.

Residents in other villages, however, have complained about basketball courts being turned into parking lots or trash piles. Sometimes conflicting policies are to blame: In Xilong village in Guangdong province, a basketball court was suddenly turned into a sweet potato field in 2021, as local officials scrambled to answer the call from the Ministry of Land and Resources to restore farmlands.

Even when facilities are built, lack of awareness often keeps villagers from incorporating sports into their daily lives. A survey across eight provinces run by scholars of Peking University and Beijing Normal University published in 2020 found that “22.03 percent (764) of the sampled households did not know that their villages had public sports facilities, while 33.42 percent (1,159) of them did not know about the public sports activities organized by their villages.”

Some suggest sports are unnecessary. “In our village, people don’t really have a concept of sports, but they are not just sitting around,” observes Wu Wenjie, a resident of Peitian village in Fujian province in his 20s, who has returned to the village after graduation from university to run education and cultural heritage initiatives.

He shares with TWOC that even though the village has not organized sports-related activities, villagers get their share of physical activity by taking walks, fishing, or climbing the mountains nearby to forage for wild fruits, herbs, or bamboo shoots. “Only city dwellers feel the need to find time to do sports. For us in rural areas, most of our day-to-day job is already exercising.”

– Siyi Chu (褚司怡)

Residents at Yugouliang village, Hebei province, practice yoga together on a brick bed

A villager strikes a headstand on the pasture outside of Yugouliang

Hongxi village playing against Hongnan village in an inter-village basketball championship in 2018

Hongxi’s basketball team celebrates a provincial level farmer’s basketball competition victory

The Hot Mama Babies turn heads during the 2017 China Basketball Village Championship finals