社交媒体使用对执行功能的影响:有益还是有害?*

2022-02-18麻雅洁贺相春任丽萍

麻雅洁 赵 鑫 贺相春 任丽萍

社交媒体使用对执行功能的影响:有益还是有害?*

麻雅洁1,2赵 鑫1,2贺相春3任丽萍1,2

(1甘肃省行为与心理健康重点实验室;2西北师范大学心理学院;3西北师范大学教育技术学院, 兰州 730070)

社交媒体使用对执行功能的影响尚存争议, 这与社交媒体使用强度起到的调节作用有关。中等强度的社交媒体使用会产生社交媒体心流体验, 使注意集中于目标信息, 并为个体提供了持续不断的社会奖励和情感支持, 对执行功能有益, 但高、低强度社交媒体使用则会损害执行功能。今后该领域的研究应该探讨社交媒体使用影响执行功能的“剂量效应”以及社交媒体使用类型对执行功能的具体影响, 还应关注不同认知水平的个体, 以进一步明确社交媒体使用与执行功能发展的关系。

社交媒体, 执行功能, 心流体验

1 引言

社交媒体(social media)是一种建立在互联网技术, 特别是Web 2.0基础之上的用以构建社会关系和获取信息的应用平台(Andreas & Michael, 2010)。社交媒体使用则是基于社交媒体开展的各种活动的总称, 目前研究者主要从使用频率、使用时间、使用强度及使用成瘾等角度来衡量社交媒体的使用程度(Mieczkowski et al., 2020; 张亚利等, 2021)。已有研究表明, 社交媒体的使用可以帮助个体形成积极的自我概念(Gentile et al., 2012)、促进人际交流(Torous & Keshavan, 2016)、获得社会支持(Huang & Liu, 2017), 发展社会资本(Bucci et al., 2019)。但是, 社交媒体使用也会给个体带来一系列负面的影响, 如, 可能会导致抑郁症状(Lin et al., 2016;Twenge & Campbell, 2019)、自尊水平下降(Sherlock & Wagstaff, 2018)、睡眠障碍(van der Schuur et al., 2019)、外貌焦虑(Vannucci et al., 2017)和身材焦虑(Frost & Rickwood, 2017; Sherlock & Wagstaff, 2018)等不良结果。同时, 社交媒体使用还会导致个体的认知能力下降, 尤其是对个体的执行功能(executive function, EF)有消极影响(Baumgartner et al., 2014; Parry & le Roux, 2019)。执行功能是指以目标为导向对多种认知加工进行监控和管理的能力(Miller & Cohen, 2001; Miyake et al., 2000), 包括一系列的高级认知加工过程, 其中转换(“switching ”or “shifting”)、刷新(updating)、抑制(inhibition)三个独立的成分一直受到研究者的诸多关注。但近期有研究发现, 使用社交媒体反而对个体的执行功能有益, 如练习使用社交媒体的新手用户在刷新和抑制能力上表现出显著提高(Myhre et al., 2017; Quinn, 2018)。而Shin等人(2020)认为, 社交媒体使用可能与个体的执行功能之间呈倒U型关系, 即中等程度的社交媒体使用是促进执行功能的最佳水平。因此, 社交媒体使用对执行功能的影响还存在一定的争议, 本文旨在系统回顾社交媒体使用对个体执行功能影响的研究现状, 为未来针对如何降低社交媒体使用对执行功能的消极影响, 促进其积极作用提供思路。

2 社交媒体使用影响执行功能的表现

2.1 社交媒体使用对执行功能的积极效应

2.2 社交媒体使用对执行功能的消极效应

虽然已有研究发现社交媒体使用会对个体的执行功能有促进作用, 但是另外一些研究发现, 社交媒体使用会损害个体的执行功能(van der Schuur et al., 2019; Wiradhany & Nieuwenstein, 2017; Wiradhany & Koerts, 2019; Madore et al., 2020; Parry et al., 2020)。通过纵向研究发现, 由于越来越多的社交媒体使用取代了对幼儿认知发展有重要作用的活动, 例如操纵游戏和想象力游戏等, 从而可能导致日后幼儿的执行功能整体的发展受到永久性的负面影响(Mcharg et al., 2020)。有研究对185名学龄前儿童进行为期一年的追踪, 发现在控制相关协变量之后, 大量使用应用程序(≥30分钟/天)的学龄前儿童与少量使用应用程序(< 30分钟/天)的相比, 抑制控制能力更差(Mcneill et al., 2019)。针对青少年群体进一步展开研究, 结果表明, 较高的媒体多任务处理得分与个体执行功能的表现(包括工作记忆、转换和抑制任务)均呈负相关(Baumgartner et al., 2014; Cain et al., 2016)。高强度媒体多任务的大学生在完成Eriksen Filter任务、AX-CPT任务、2-back和3-back任务时, 其反应速度和准确性均差于低强度组, 难以将注意力集中在当前的任务上, 并且具有更多自下而上的注意偏向(Ophir et al., 2009)。Magen (2017)以18~36岁个体为研究对象, 使用健康成人执行功能行为评分量表(BRIEF-A, Roth et al., 2013)测验发现, 频繁在电子媒体上同时处理多项任务与较差的执行功能有关, 并且社交媒体使用频率越高, 执行功能方面存在越多的困难(Zurcher et al., 2020), 尤其表现在反应抑制能力上(Murphy & Creux, 2021)。研究者发现, 高强度媒体多任务者比低强度媒体多任务者倾向于更多地使用直觉反应系统, 并且关注即时满足而非延迟满足(Schutten et al., 2017), 这表明媒体多任务处理可能损害个体的抑制控制能力(Baumgartner & Wiradhany, 2021)。

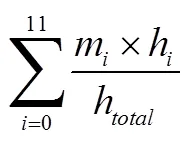

2.3 社交媒体使用与执行功能之间呈倒U型关系

大多数研究表明, 社交媒体使用与认知能力之间存在线性关系(Ophir et al., 2009; Alzahabi & Becker, 2013; Ralph & Smilek, 2017; Elbe et al., 2019; Zurcher et al., 2020; Murphy & Creux, 2021), 而有研究者提出, 社交媒体使用可能与个体的执行功能水平之间呈倒U型关系, 社交媒体使用并不是一味地损害或促进执行功能的发展, 而是在二者之间存在一个最佳临界点。研究表明, 在n-back任务中, 中等强度媒体多任务者比高、低强度媒体多任务者表现更好(Minear et al., 2013; Shin et al., 2020), 中等强度的媒体多任务处理与最佳水平的认知控制相关(例如, 刷新工作记忆中的信息, 过滤干扰刺激) (Cardoso-Leite et al., 2016)。高强度媒体多任务者在n-back任务中更容易出现注意力缺失, 更难以专注于任务, 这导致他们停止刷新短时记忆中的字母, 因此更难记住字母顺序, 抑制控制能力更差(Ralph & Smilek, 2017)。低强度媒体多任务者在执行功能任务中的表现比中等媒体多任务者更差, 与高强度媒体多任务者无显著差异(Cardoso-Leite et al., 2016)。研究者认为, 这可能是由于低强度媒体多任务处理与消极情绪状态有关,使个体自我控制能力和成就感降低, 进而阻碍执行功能的发展(Sanbonmatsu et al., 2013)。

3 使用强度调节社交媒体使用与执行功能之间的关系

社交媒体使用与个体的执行功能呈倒U型关系, 中等程度的社交媒体使用之所以是促进执行功能的最佳水平, 一个重要原因可能是, 相比于高强度或低强度的社交媒体使用水平, 中等强度的社交媒体使用会引发更高水平的社交媒体心流(Katahira et al., 2018; de Sampaio Barros et al., 2018; Harmat et al., 2015; Keller & Bless, 2008; Keller et al., 2011; Yoshida et al., 2014)。社交媒体心流(social media flow, SM flow)是当人们完全沉浸于使用智能手机等电子工具进行娱乐、信息搜索和社交活动时, 所产生的一种最佳体验, 表现为在使用社交媒体时持续专注和愉悦的心理状态(Leung, 2020)。通常采用专注、时间失真、临场呈现、享受和好奇五个维度来评估社交媒体心流的程度(Kwak et al., 2014)。当社交媒体使用强度处于适中水平时, 社交媒体心流处于一种无需任何心理努力的特殊注意状态(Ullén et al., 2010), 与个体高水平的认知控制、专注投入有关(Katahira et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2013), 使得个体在面对社交媒体中各种复杂的信息刺激时, 过滤各种干扰信息, 将注意集中于有用的信息, 目标信息则不断地被储存和更新, 个体的执行功能(尤其是刷新功能)在这样的要求下得到长期而反复的锻炼, 最终得以提升(Alloway et al., 2013)。此外, 社交媒体使用所产生的心流体验可以作为一种内在使用动机, 通过增加社交网络的互动, 使得人际关系的积极变化(Kwak et al., 2014), 这也为个体提供了持续不断的社会奖励, 包括各种关于社交联系或声誉提升的功能(Meshi et al., 2015)。形成和维持社会互动与奖赏相关的神经系统有关, 当个体接收来自社交媒体的积极社会反馈时(例如, 得到别人的点赞、评论等)可以激活有关社会奖励的大脑区域(Sherman et al., 2016), 包括纹状体和腹侧被盖区(Fareri & Delgado, 2014; Ruff & Fehr, 2014; Sherman et al., 2018)。因此, 当个体适度使用社交媒体, 作为改善其现有社会资本的工具时, 则会对执行功能起到保护作用(Sanbonmatsu et al., 2013; Khoo & Yang, 2020; Baumgartner & Wiradhany, 2021), 能在一定程度上缓冲过度使用社交媒体对认知功能的消极影响, 减缓与年龄有关的执行功能衰退(Myhre et al., 2017; Quinn, 2018; Glaser et al., 2018)。社交媒体心流可以扩大和维护社会关系来获得更多的情感支持, 从而对执行功能(尤其是抑制能力)有益(Zuelsdorff et al., 2019)。

因此, 中等强度的社交媒体使用会产生更高水平的社交媒体心流, 使注意集中于目标信息, 并为个体提供了持续不断的社会奖励和情感支持, 从而使得执行功能最终得以提升。

前人通过研究发现, 社交媒体心流与注意活动的神经生理学指标高度相关(Yoshida et al., 2014), 即个体在社交媒体使用时所产生的心流体验与外侧额叶皮层(额下回)的激活增加和内侧前额叶皮层的激活减少有关(Ulrich et al., 2014; Yoshida et al., 2014), 由于额顶叶网络的外侧部分通常参与自上而下的注意和任务中的持续注意(Corbetta & Schulman, 2002), 而内侧额叶皮层经常与任务中出现的思维游离和自我专注有关(Esterman et al., 2014), 当自我控制资源由于执行其他媒体任务而处于损耗状态时, 这种自上而下的认知控制损耗会降低前额叶功能的相对优势, 进而导致执行功能失败(Berkman & Miller-Ziegler, 2012), 从而导致个体无法控制自己的注意力或自我调节行为, 而注意力的集中以及忽视干扰刺激的能力是执行功能的核心(Farah, 2017)。因此在频繁进行媒体多任务的过程中, 个体会接收和处理大量杂乱且分散的信息, 这种高强度的社交媒体使用导致个体担心他们在任务中的表现(de Sampaio Barros et al., 2018), 从而形成一定的注意偏好(认知倾向), 即保持更广的注意范围, 倾向于同时平行加工多个信息(包括无关信息), 这使个体更容易受到无关信息的干扰(Ophir et al., 2009; Cain & Mitroff, 2011)。在这种易受干扰的状态下, 个体难以将注意集中于目标信息, 从而对个体执行功能有消极影响(Magen, 2017)。

而低强度社交媒体使用与低感觉寻求有关(Chang, 2017), 不仅会降低社交媒体心流水平, 导致个体处于缺乏积极主动性的状态, 缺乏愉悦感, 负面情绪增加(Lin et al., 2016; Brailovskaia et al., 2020; Dube et al., 2020), 并且因为社交媒体本身就具有存储信息的功能, 个体会更少地加工和存储信息, 这使得信息加工的心理努力过程缩减甚至消失(Sparrow et al., 2011), 任务投入度降低(Wu et al., 2013), 人们只需记住一些关于信息的线索而无需记住信息本身, 个体大脑的认知功能被社交媒体所替代, 久而久之, 个体的认知功能失去训练的机会, 当脱离了社交媒体后, 便无法对当前信息进行有效地存储和加工, 信息处理不足, 从而对个体的执行功能有负面影响(Kahn & Martinez, 2020)。

因此, 高强度的社交媒体使用导致个体担心他们在任务中的表现, 从而倾向于保持更广的注意范围, 更易受到无关信息的干扰, 而低强度的社交媒体使用导致个体处于缺乏积极主动性的状态, 信息加工的心理努力过程缩减甚至消失, 从而对执行功能产生消极影响。

4 研究展望

综上所述, 社交媒体使用对执行功能的影响尚存争议, 使用强度可能在二者关系中起调节作用, 未来仍有一些问题需要进一步探索。

首先, 关注社交媒体使用对执行功能的“剂量效应”, 即社交媒体使用不同测量指标(社交媒体使用成瘾; 使用时间; 使用频率; 使用强度)单独和交互作用对执行功能的影响。研究发现, 社交媒体纵向地以“特质”的方式, 而不是简单地以短期的“状态”效应影响执行功能发展(McHarg et al., 2020), 如果个体保持适度的使用时间和频率, 社交媒体使用对执行功能的消极影响可能不会出现(Mcneill et al., 2019)。因此, 社交媒体使用对执行功能的积极影响可能需要一个相对较长和持续使用社交媒体的过程(Khoo & Yang, 2020)。是否能确定一个最佳的社交媒体使用水平, 使得个体的执行功能得到最大提升? 今后可以展开更多的追踪研究, 考察社交媒体使用作为连续变量时对执行功能的影响。

其次, 进一步明晰不同类型的社交媒体使用与执行功能子成分之间的关系。目前研究主要侧重于社交媒体使用频率对个体日常生活中执行功能的影响研究(Cardoso-Leite et al., 2016; Khoo & Yang, 2020), 而缺乏对社交媒体使用类型对执行功能中的单个子成分发展变化的考察。已有研究发现, 主动性社交媒体使用有助于个体的认知发展(Wang et al, 2014; Xie, 2014), 而被动性社交媒体使用会对个体的认知发展有害(Tandoc et al., 2015), 致使这种分离效应的原因在于二者的“目的性”明确与否。此外, 媒体多任务处理作为个体在日常生活中的一种习惯化媒体使用模式, 具有很高的自主选择性(Seddon et al., 2021), 个体如何根据个人的注意中心和认知资源选择高效率的媒体多任务类型, 避免媒体多任务间的相互影响, 最大化利用媒体多任务处理达到社交媒体心流状态, 从而对个体的执行功能具有促进作用?未来的研究应进一步细化探究社交媒体使用类型对执行功能的具体影响, 为改善个体的认知状况, 提高执行功能提供相应的建议。

最后, 未来研究需要关注不同认知水平的个体, 以进一步明确社交媒体使用与执行功能发展的关系。已有研究表明, 执行功能与前额叶密切相关(Gianaros et al., 2007), 社交媒体使用与前额叶的关联在不同的年龄阶段存在差异, 社交媒体使用的提升效应可能在大脑结构处于变化时期的群体中更为显著, 例如, 相较于大脑结构相对稳定的成年人, 处于发育阶段的学龄前儿童和处于退化阶段的老年人在使用社交媒体后, 执行功能获益更多(Chan et al., 2016; McNeill et al., 2019; Myhre et al, 2017; Quinn, 2018; Huber et al., 2018; Khoo & Yang, 2020)。以往研究大多只表明了社交媒体使用会改变个体的神经通路或大脑的反应模式(Meshi et al., 2015; Sherman et al., 2018; Kei et al., 2020), 而对于有关执行功能的生理结构变化是否存在社交媒体使用者认知水平的影响知之甚少, 因此, 未来研究应结合行为与认知神经方法, 考察不同认知水平社交媒体使用者在执行功能特定任务中脑区激活的差异, 从而使社交媒体使用影响执行功能的神经机制研究更精确也更全面。

张亚利, 李森, 俞国良. (2021). 社交媒体使用与错失焦虑的关系:一项元分析.(3), 273–290.

Alloway, T. P., Horton, J., Alloway, R. G., & Dawson, C. (2013). Social networking sites and cognitive abilities: Do they make you smarter?,, 10–16.

Alzahabi, R., & Becker, M. W. (2013). The association betweenmedia multitasking, task-switching, and dual-task performance.:,(5), 1485–1495.

Andreas, M. K., & Michael, H. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media.,(1), 59–68.

Baumgartner, S. E., Weeda, W. D., van der Heijden, L. L., & Huizinga, M. (2014). The relationship between media multitasking and executive function in early adolescents.,(8), 1120–1144.

Baumgartner, S. E., & Wiradhany, W. (2021). Not all media multitasking is the same: The frequency of media multitaskingdepends on cognitive and affective characteristics of media combinations.. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000338.

Berkman, E. T., & Miller-Ziegler, J. S. (2012). Imaging depletion: FMRI provides new insights into the processes underlying ego depletion.,(4), 359–361.

Brailovskaia, J., Schillack, H., & Margraf, J. (2020). Tell me why are you using social media (SM)! Relationship between reasons for use of SM, SM flow, daily stress, depression, anxiety, and addictive SM use - An exploratory investigation of young adults in Germany - sciencedirect.,, Article e106511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106511.

Brasel, S. A., & Gips, J. (2011). Media multitasking behavior: Concurrent television and computer usage.,(9), 527–534.

Bucci, S., Schwannauer, M., & Berry, N. (2019). The digital revolution and its impact on mental health care.,(2), 277–297.

Cain, M. S., Leonard, J. A., Gabrieli, J. D. E., & Finn, A. S. (2016). Media multitasking in adolescence.,(6), 1932–1941.

Cain, M. S., & Mitroff, S. R. (2011). Distractor filtering in media multitaskers.,(10), 1183–1192.

Cardoso-Leite, P., Kludt, R., Vignola, G., Ma, W. J., Green, C. S., & Bavelier, D. (2016). Technology consumption and cognitive control: Contrasting action video game experiencewith media multitasking.,(1), 218–241.

Chan, M. Y., Haber, S., Drew, L. M., & Park, D. C. (2016). Training older adults to use tablet computers: Does it enhance cognitive function?,(3), 475–484.

Chang, Y. (2017). Why do young people multitask with multiple media? Explicating the relationships among sensation seeking, needs, and media multitasking behavior.,(4), 685–703.

Corbetta, M., & Shulman, G. L. (2002). Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain.,(3), 201–215.

de Sampaio Barros, M. F., Araújo-Moreira, F. M., Trevelin, L. C., & Radel, R. (2018). Flow experience and the mobilization of attentional resources.,(4), 810–823.

Dube, S. L., Sigmon, S., Althoff, R. R., Dittus, K., Gaalema, D. E., Ogden, D. E., … Potter, A. S. (2020). Association of self-reported executive function and mood with executive function task performance across adult populations.. Article e23279095. https://doi.org/10.1080/23279095.2020.1794869.

Elbe, P., Sörman, D. E., Mellqvist, E., Brändström, J., & Ljungberg, J. K. (2019). Predicting attention shifting abilities from self-reported media multitasking.,(4), 1257–1265.

Esterman, M., Rosenberg, M. D., & Noonan, S. K. (2014). Intrinsic fluctuations in sustained attention and distractor processing.,(5), 1724–1730.

Farah, M. J. (2017). The neuroscience of socioeconomic status: Correlates, causes, and consequences.,(1), 56–71.

Fareri, D. S., & Delgado, M. R. (2014). Social rewards and social networks in the human brain.,(4), 387–402.

Frost, R. L., & Rickwood, D. J. (2017). A systematic review of the mental health outcomes associated with Facebook use.,, 576–600.

Gentile, B., Twenge, J. M., Freeman, E. C., & Campbell, W. K. (2012). The effect of social networking websites on positive self-views: An experimental investigation.,(5), 1929–1933.

Gianaros, P. J., Horenstein, J. A., Cohen, S., Matthews, K. A., Brown, S. M., Flory, J. D. … Hariri, A. R. (2007). Perigenual anterior cingulate morphology covaries with perceived social standing.,(3), 161–173.

Glaser, P., Liu, J. H., Hakim, M. A., Vilar, R., & Zhang, R. (2018). Is social media use for networking positive or negative? Offline social capital and internet addiction as mediators for the relationship between social media use and mental health.,(3), 11–17.

Harmat, L., de Manzano, Ö., Theorell, T., Högman, L., Fischer, H., & Ullén, F. (2015). Physiological correlates of the flow experience during computer game playing.,(1), 1–7.

Huang, L. V., & Liu, P. L. (2017). Ties that work: Investigating the relationships among coworker connections, work-related facebook utility, online social capital, and employee outcomes.,, 512–524.

Huber, B., Yeates, M., Meyer, D., Fleckhammer, L., & Kaufman, J. (2018). The effects of screen media content on young children’s executive functioning.,, 72–85.

Judd, T., & Kennedy, G. (2011). Measurement and evidence of computer-based task switching and multitasking by ‘Net generation’ students.,(3), 625–631.

Kahn, A. S., & Martinez, T. M. (2020). Text and you might miss it? Snap and you might remember? Exploring “Google effects on memory” and cognitive self-esteem in the context of Snapchat and text messaging.,, Article e106166. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.chb.2019.106166.

Katahira, K., Yamazaki, Y., Yamaoka, C., Ozaki, H., Nakagawa, S., & Nagata, N. (2018). EEG correlates of the flow state: A combination of increased frontal theta and moderate frontocentral alpha rhythm in the mental arithmetic task.,, 1–11.

Kei, K., Naoya, O., Sayaka, Y., Tsukasa, U., Takashi, M., Toshiya, M., & Hironobu, F. (2020). Relationship between media multitasking and functional connectivity in the dorsal attention network.,(1), 17992. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75091-9.

Keller, J., & Bless, H. (2008). Flow and regulatory compatibility: An experimental approach to the flow model of intrinsic motivation.,(2), 196–209.

Keller, J., Bless, H., Blomann, F., & Kleinböhl, D. (2011). Physiological aspects of flow experiences: Skills-demand- compatibility effects on heart rate variability and salivary cortisol.,(4), 849–852.

Khoo, S. S., & Yang, H. (2020). Social media use improves executive functions in middle-aged and older adults: A structural equation modeling analysis.,, Article e106388. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.chb.2020.106388.

Kwak, K. T., Choi, S. K., & Lee, B. G. (2014). SNS flow, SNS self-disclosure and post hoc interpersonal relations change: Focused on Korean Facebook user.,, 294–304.

Leung, L. (2020). Exploring the relationship between smartphone activities, flow experience, and boredom in free time.,, 130–139.

Lin, L. Y., Sidani, J. E., Shensa, A., Radovic, A., Miller, E., Colditz, J. B., … Primack, B. A. (2016). Association between social media use and depression among U.S. young adults.,(4), 323–331.

Lui, K. F. H., & Wong, A. C. -N. (2012). Does media multitasking always hurt? A positive correlation between multitasking and multisensory integration.,(4), 647–653.

Madore, K. P., Khazenzon, A. M., Backes, C. W., Jiang, J., Uncapher, M. R., Norcia, A. M., & Wagner, A. D. (2020). Memory failure predicted by attention lapsing and media multitasking.(7832), 87–91.

Magen, H. (2017). The relations between executive functions, media multitasking and polychronicity.,, 1–9.

Mcharg, G., Ribner, A. D., Devine, R. T., & Hughes, C. (2020). Screen time and executive function in toddlerhood: A longitudinal study.,, Article e570392.https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.570392.

Mcneill, J., Howard, S. J., Vella, S. A., & Cliff, D. P. (2019). Longitudinal associations of electronic application use and media program viewing with cognitive and psychosocial development in preschoolers.,(5), 520−528.

Meshi, D., Tamir, D. I., & Heekeren, H. R. (2015). The emerging neuroscience of social media.,(12), 771–782.

Mieczkowski, H., Lee, A. Y., & Hancock, J. T. (2020). Priming effects of social media use scales on well-being outcomes: The influence of intensity and addiction scales on self-reported depression.,(4), 1–15.

Miller, E. K., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function.,(1), 167–202.

Minear, M., Brasher, F., McCurdy, M., Lewis, J., & Younggren, A. (2013). Working memory, fluid intelligence, and impulsiveness in heavy media multitaskers.,(6), 1274–1281.

Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., Howerter, A., & Wager, T. D. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “Frontal Lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis.,(1), 49–100.

Monsell, S. (2003). Task switching.,(3), 134–140.

Murphy, K., & Creux, O. (2021). Examining the association between media multitasking, and performance on working memory and inhibition tasks.,, Article e106532. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.chb.2020.106532.

Myhre, J. W., Mehl, M. R., & Glisky, E. L. (2017). Cognitive benefits of online social networking for healthy older adults.,(5), 752–760.

Ophir, E., Nass, C., & Wagner, A. D. (2009). Cognitive control in media multitaskers.,(37), 15583–15587.

Parry, D. A., & le Roux, D. B. (2019). Media multitasking and cognitive control: A systematic review of interventions.,, 316–327.

Parry, D. A., le Roux, D. B., & Bantjes, J. R. (2020). Testing the feasibility of a media multitasking self-regulation intervention for students: Behaviour change, attention, and self-perception.,, Article e106182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106182.

Quinn, K. (2018). Cognitive effects of social media use: A case of older adults.,(3), Article e20563051. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118787203.

Ralph, B. C. W., & Smilek, D. (2017). Individual differences in media multitasking and performance on the-back.,(2), 582–592.

Rogobete, D. A., Ionescu, T., & Miclea, M. (2020). The relationship between media multitasking behaviorand executive function in adolescence: A replication study.,(5), 725–753.

Roth, R. M., Lance, C. E., Isquith, P. K., Fischer, A. S., & Giancola, P. R. (2013). Confirmatory factor analysis of the behavior rating inventory of executive function-adult version in healthy adults and application to attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder.,(5), 425–434.

Ruff, C. C. & Fehr, E. (2014). The neurobiology of rewards and values in social decision making..(8), 549–562.

Sanbonmatsu, D., Strayer, D., Medeiros-Ward, N., & Watson, J. (2013). Who multi-tasks and why? Multi-tasking ability, perceived multi-tasking ability, impulsivity, and sensation seeking.,(1), Article e0054402. https://doi. org/10.1371/journal.pone.0054402.

Schutten, D., Stokes, K. A., & Arnell, K. M. (2017). I want to media multitask and I want to do it now: Individual differences in media multitasking predict delay of gratification and system-1 thinking.,(1), 8–18.

Seddon, A. L., Law, A. S., Adams, A. M., & Simmons, F. R. (2021). Individual differences in media multitasking ability: The importance of cognitive flexibility.,(1), Article e100068. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100068.

Sherlock, M., & Wagstaff, D. L. (2018). Exploring the relationship between frequency of instagram use, exposure to idealized images, and psychological well-being in women.,(4). 482–490.

Sherman, L. E., Hernandez, L. M., Greenfield, P. M., & Dapretto, M. (2018). What the brain ‘likes’: Neural correlates of providing feedback on social media.,(7), 699–707.

Sherman, L. E., Payton, A. A., Hernandez, L. M., Greenfield, P. M., & Dapretto, M. (2016). The power of the like in adolescence: Effects of peer influence on neural and behavioral responses to social media.,(7), 1027–1035.

Shin, M., Linke, A., & Kemps, E. (2020). Moderate amounts of media multitasking are associated with optimal task performance and minimal mind wandering.,, Article e106422. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106422.

Sparrow, B., Liu, J., & Wegner, D. M. (2011). Google effects on memory: Cognitive consequences of having information at our fingertips.,(6043), 776–778.

Tandoc, E. C., Ferrucci, P., & Duffy, M. (2015). Facebook use, envy, and depression among college students: is facebooking depressing?,, 139–146.

Torous, J., & Keshavan, M. (2016). The role of social media in schizophrenia: Evaluating risks, benefits, and potential.,(3), 190–195.

Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Media use is linked to lower psychological well-being: Evidence from three datasets.,(2), 311–331.

Ullén, F., de Manzano, Ö., Theorell, T., & Harmat, L. (2010). The physiology of effortless attention: Correlates of state flow and flow proneness. In B. Bruya (Ed.),(pp. 205−217, Chapter viii). MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Ulrich, M., Keller, J., Hoenig, K., Waller, C., & Grön, G. (2014). Neural correlates of experimentally induced flow experiences.,, 194–202.

Uncapher, M. R., & Wagner, A. D. (2018). Minds and brains of media multitaskers: Current findings and future directions.,(40), 9889–9896.

van der Schuur, W. A., Baumgartner, S. E., & Sumter, S. R. (2019). Social media use, social media stress, and sleep: Examining cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships in adolescents.,(5), 552–559.

Vannucci, A., Flannery, K. M., & Ohannessian, C. M. (2017). Social media use and anxiety in emerging adults.,, 163–166.

Wang, J., Jackson, L. A., Gaskin, J., & Wang, H. (2014). The effects of social networking site (SNS) use on college students’ friendship and well-being.,, 229–236.

Wiradhany, W., & Koerts, J. (2019). Everyday functioning-related cognitive correlates of media multitasking: A mini meta- analysis.,(2), 276–303. http://dx.doi. org/10.1080/15213269.2019.1685393.

Wiradhany, W., & Nieuwenstein, M. R. (2017). Cognitive control in media multitaskers: Two replication studies and a meta-analysis.,(8), 2620–2641.

Wu, T. C., Scott D., & Yang, C. (2013). Advanced or addicted? Exploring the relationship of recreation specialization to flow experiences and online game addiction.,(3), 203–217.

Xie, W. (2014). Social network site use, mobile personal talk and social capital among teenagers.,, 228–235.

Yoshida, K., Sawamura, D., Inagaki, Y., Ogawa, K., Ikoma, K., & Sakai, S. (2014). Brain activity during the flow experience: A functional near-infrared spectroscopy study.,, 30–34.

Zuelsdorff, M. L., Koscik, R. L., Okonkwo, O. C., Peppard, P. E., Hermann, B. P., Sager, M. A., … Engelman, C. D. (2019). Social support and verbal interaction are differentially associated with cognitive function in midlife and older age.,(2), 144–160.

Zurcher, J. D., King, J., Callister, M., Stockdale, L., & Coyne, S. M. (2020). “I can multitask”: The mediating role of media consumption on executive function’s relationship to technoference attitudes.,, Article e106498.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106498.

The impact of social media on executive functions:Beneficial or harmful?

MA Yajie1,2, ZHAO Xin1,2, HE Xiangchun3, REN Liping1,2

(1Key Laboratory of Behavioral and Mental Health of Gansu province, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou 730070, China)(2School of Psychology, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou 730070, China)(3School of Educational Technical, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou 730070, China)

The effect of social media on executive functions remain controversial. it has to do with social media use intensity inverted U-shaped regulating effect on moderate social media use will generate social media flow, make the attention focused on the target information, and provides individuals with ongoing social rewards and emotional support, beneficial to perform functions, but high and low intensity use social media will damage the executive function. Future research in this area should examine the implications of using social media to further clarify the link between social media use and the development of executive functions. The research should include the dose-effect of social media on executive functions and the use of social media to perform functions, taking individuals' different cognitive levels into account.

social media, executive function, flow experience

B849: C91

2021-04-28

* 国家自然科学基金(31560283, 62167007), 教育部人文社会科学研究项目(21XJA190005), 甘肃省“双一流”科研重点项目(GSSYLXM-01)和西北师范大学重大科研项目培育计划(NWNU-SKZD2021-06)资助。

赵鑫, E-mail: psyzhaoxin@nwnu.edu.cn; 贺相春, E-mail: hxc@nwnu.edu.cn。