Predictors of thirty-day readmission in nonagenarians presenting with acute heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a nationwide analysis

2022-01-14AhmedMaraeyMahmoudSalemNabilaDawoudMahmoudKhalilAhmedElzanatyHadeerElsharnobyAhmedYounesAhmedHashimAmitAlam11

Ahmed Maraey, Mahmoud Salem, Nabila Dawoud, Mahmoud Khalil, Ahmed Elzanaty,Hadeer Elsharnoby, Ahmed Younes, Ahmed Hashim, Amit Alam,11,✉

1. Department of Internal Medicine, the CHI St. Alexius Health, Bismarck, USA; 2. Department of Internal Medicine,University of North Dakota, Bismarck, USA; 3. Center for Advanced Heart and Lung Diseases, Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, USA; 4. Department of Internal Medicine, University of Kentucky, Lexington, USA; 5. Department of Internal Medicine, Lincoln Medical Center Weil Cornell University, Bronx, USA; 6. Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Tanta University, Tanta, Egypt; 7. Department of Cardiovascular Disease, University of Toledo, Toledo, USA; 8. Faculty of Medicine,Tanta University, Tanta, Egypt; 9. Department of Internal Medicine, East Carolina University, Greenville, USA; 10. Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt; 11. College of Medicine, Texas A&M Health Science Center, Dallas, USA

ABSTRACT

By 2030, it is estimated that one every thirtythree patients will have the diagnosis of heart failure (HF). The projected cost estimates of treating HF are 160 billion United States dollars (USD) in direct costs. Because of the aging of the population, greater increase in HF prevalence will be seen in older adults. It is projected that the number of patients > 80 years with HF will grow by 66% by 2030.[1]

HF incidence and prevalence rise dramatically with age due to structural and functional alterations in the cardiovascular system, making HF the most prevalent cardiovascular disease among elderly. HF was reported to be the second leading cause of hospitalization for patients aged 75 years and above from 2013 to 2018.[2]

Most elderly patients with HF have impaired left ventricular diastolic function without significant impairment in left ventricular systolic function,which is called heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).[3–6]Increased levels of brain natriuretic peptide, older age, myocardial infarction history, and reduced diastolic function make the prognosis of HFpEF worse.[7–9]

Over the years, there have been advances in the treatment of HF, however, the mortality, hospitalization, and readmission rates are still high.

In this study, we aimed to assess the predictors and causes of readmissions with acute HFpEF among nonagenarians in the United States, by using the National Readmission Database (NRD).

METHODS

Data Source

This is a retrospective cohort study using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) NRD from January 2016 to December 2018.[10]The NRD is the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient health care readmission database in the United States. The NRD is drawn from HCUP State Inpatient Databases containing verified patient linkage numbers that can be used to track a person across hospitals within a State, while adhering to strict privacy guidelines. Unweighted, the NRD contains data from approximately 18 million discharges in the United States each year. Weighted, it estimates roughly 35 million discharges in the United States each year.

The NRD contains both patient and hospital-level information. Up to forty discharge diagnoses and twenty-five procedures are collected for each patient using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM). Patients were tracked during the same year using the variable “nrd_visitlink”, and time between two admissions was calculated using variable“nrd_daystoevent”. National estimates were produced using sampling weights provided by the sponsor. All values presented are weighted estimates.

Study Population

Our study population was patients aged 90 years and above admitted between January 2016 and December 2018 with a primary diagnosis of diastolic HF (ICD-10 codes: I50.30, I50.31, and I50.33). Unfortunately, no ICD codes exclusively existed for HFpEF for our patient population. We excluded patients with systolic failure or combined systolic/diastolic HF, and patients who were discharged in December each year to allow thirty-day follow-up.Patients who died in index admission were excluded from evaluating readmission outcomes but included in other secondary outcomes pertaining to index admission only.

NRD variables were used to identify patients and hospital characteristics. Patient characteristics included age, gender, median household income, and primary insurance. Hospital characteristics included hospital bed size and teaching status. ICD-10 codes used in our analysis are included in Table 1.

In accordance with the HCUP data use agreement,we excluded any variable containing a small number of observations (≤ 10) that could pose risk of person identification or data privacy violation.

Missing Data

Data on median household income and primary insurance were missing in 1.09% and 0.06% of hospitalizations, respectively. Other key variables had no missing values. In-hospital mortality and total charges outcomes were missing in 0.06% and 1.54%of hospitalizations, respectively. All hospitalizations with missing values were excluded from our analysis.

Study Outcomes

Primary outcome was thirty-day readmission.Secondary outcomes were in-hospital mortality, length of stay (LOS), and total hospital charges in index admission. In-hospital morality, LOS, and total hospital charges were directly coded in NRD.

Index admission was defined as the first admission with the primary diagnosis of diastolic HF without prior admission in the thirty-day period. A readmission was defined as any readmission within thirty days of the index admission. For patients whowere readmitted multiple times during the thirtyday post admission, only the first readmission was included.

Table 1 The ICD-10-CM used to identify key variables.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using STATA 17.0(StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). Data were expressed as a percentage for categorical variables and mean ± SD for continuous variables. Univariate regression analysis was used to calculate unadjusted odds ratio for the primary and secondary outcomes. Multivariate regression analysis was used to adjust for the potential confounders and calculate adjusted odds ratio (aOR). A logistic regression model was used for binary outcome and linear regression for continuous outcome. The models were built by including the variables that were associated with the outcome of interest on univariable regression analysis with a cut-offP-value of 0.20. Continuous variables were compared using the independent Student’st-test and categorical variables were compared using the Pearson’s chisquared test. All statistical tests were two-sided,andP-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

From 107 million discharges included in NRD from January 2016 to December 2018, our cohort included 45,393 index admissions of whom 43,646 patients (96.2%) survived to discharge. A total of 7,437 patients were readmitted in thirty-day period post discharge from index hospitalization. Baseline characteristics were stratified according to readmission status.

Female constituted 70.3% of readmitted patients.Medicare was the primary insurance in both groups(P= 0.042). Patients who were readmitted were more likely to have chronic ischemic heart disease(40.8%vs.36.8%,P< 0.001), chronic kidney disease(CKD) stage III or higher (21.8%vs.16.8%,P<0.001), chronic pulmonary disease (33.2%vs.29.8%,P< 0.001), diabetes mellitus (25.6%vs.21.6%,P<0.001), and hypertension (77.7%vs.75.2%,P=0.002). Readmitted patients had less palliative care encounter (2.3%vs.7.8%,P< 0.001). Other patient and hospital characteristics are included in Table 2.

Thirty-day Readmission

Of 43,646 patients who survived to discharge from index admission, 7,437 patients (17.0%) were readmitted within thirty days. Of those readmitted,24 patients (0.32%) were discharged to a nursing facility. The mean cost of readmission was 43,265 USD per patient. Mean LOS of readmission was 5.46 days. Readmission due to cardiovascular etiologies constituted 49% of all readmissions followed by respiratory etiologies (13%) and infectious etiologies (9%). The most common specific causes of readmission were HF (37%) followed by sepsis (8%)and pneumonia (6%). Etiologies of readmission are presented in Figure 1.

Independent predictors of readmission were admission to teaching hospital (aOR = 1.09, 95% CI: 1.01–1.18,P= 0.021), chronic ischemic heart disease (aOR =1.11, 95% CI: 1.02−1.22,P= 0.022), CKD stage III or higher (aOR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.07−1.34,P= 0.002), chronic pulmonary disease (aOR = 1.14, 95% CI: 1.05−1.23,P=0.001), diabetes mellitus (aOR = 1.18, 95% CI: 1.07−1.29,P= 0.001), fluid and electrolyte disorders (aOR =1.13, 95% CI: 1.05−1.22,P= 0.002), and LOS greater than two days (aOR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.09−1.32,P< 0.001).Female (aOR = 0.90, 95% CI: 0.82−0.99,P= 0.028),and palliative care encounter (aOR = 0.27, 95% CI: 0.21−0.34,P< 0.001), were independently associated with decreased odds of readmission (Table 3).

In-hospital Mortality

A total of 1,727 patients died in index hospitalization. Independent predictors of in-hospital mortality were private insurance (aOR = 2.07, 95% CI: 1.25−3.44,P= 0.005), acute myocardial infarction (aOR =1.40, 95% CI: 1.11−1.75,P= 0.004), CKD stage III or higher (aOR = 1.26, 95% CI: 1.01−1.58,P= 0.042), cardiac arrhythmias (aOR = 1.46, 95% CI: 1.11−1.93,P=0.007), pulmonary circulation disorder (aOR = 1.27,95% CI: 1.07−1.51,P= 0.006), paralysis (aOR = 3.81,95% CI: 1.61−9.03,P= 0.002), liver disease (aOR =2.06, 95% CI: 1.27−3.35,P= 0.003), weight loss (aOR =2.01, 95% CI: 1.63−2.49,P< 0.001), fluid and electrolyte disorders (aOR = 2.05, 95% CI: 1.77−2.37,P<0.001), and aortic stenosis (aOR = 1.36, 95% CI: 1.05−1.76,P= 0.020). Paradoxically, history of percutaneous coronary intervention (aOR = 0.61, 95% CI:0.43−0.87,P= 0.007), and dyslipidemia (aOR =0.75, 95% CI: 0.64−0.88,P< 0.001) were associated with lower odds of in-hospital mortality (Table 4).

Length of Stay

Mean LOS in our cohort was 4.72 days in index admission. Teaching hospital and large hospital size were associated with mean increased LOS of 0.29 days, and 0.44 days, respectively. Palliative care encounter was similarly associated with mean in-creased LOS of 0.79 days. Other patient characteristics such as chronic ischemic heart disease, CKD stage III or higher, pulmonary hypertension, chronic pulmonary disease, weight loss, were independently associated with mean increased LOS. All differences mentioned above were statistically significant (P<0.05) (Table 5).

Table 2 Baseline characteristics according to readmission status.

Figure 1 Etiologies of readmission.

Table 3 Predictors of thirty-day readmission.

Total Hospital Charges

Mean total hospital charges in our cohort was 32,554 USD in index admission. Size of the hospital(moderate and large) and teaching hospitals were independent predictors of increased cost of hospitalization. Medicaid insurance and palliative care encounter were similarly associated with increased cost. Other patient characteristics such as CKD stage III or higher, cardiac arrhythmias, pulmonary circulation disorders, peripheral vascular disorders,liver disease, fluid and electrolyte disorders, blood loss anemia, and aortic stenosis were amongst predictors of increased hospitalization cost (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

Patients above the age of 85 years constitute more than 9% of patients admitted to hospitals in the United States.[11]Hospitalizations and health care spending for elderly are expected to rise as the pop-ulation continues to age. Disease-specific interventions are not well studied in elderly population.[12]Several studies have documented predictors of readmission of HF in the general population.[13–17]However,few small studies evaluated HF in general or HFpEF in elderly population.[18,19]Our study is the largestand first to report data exclusively in nonagenarians presenting with HFpEF.

Table 4 Predictors of in-hospital mortality outcome.

Table 5 Predictors of increased length of stay outcome.

Table 6 Predictors of total hospital charges outcome.

In our analysis, we identified several independent predictors of readmission, in-hospital mortality, increased LOS, and total hospital costs in nonagenarians presenting with acute or acute on chronic HFpEF.

We observed a 17% thirty-day readmission rate in HFpEF nonagenarian population, which was comparable to other previous studies that documented thirty-day readmission rates from 18% to 25%.[15,20–22]Cardiovascular etiologies were responsible for 49%of readmissions, particularly HF (37%), followed by pulmonary etiologies (17%), pneumonia (6%), infectious etiologies (9%), and renal etiologies (7%). General etiologies of readmissions were similar to a study done by Arora,et al.[20]However, a higher percentage of HF readmissions was observed in our analysis which was done exclusively in nonagenarians. Our population had a high burden of chronic comorbidities, which likely have impacted readmission outcomes. We found chronic ischemic heart disease, CKD stage III or higher, chronic pulmonary disease, and diabetes mellitus to be independent predictors of readmission in nonagenarians.Although females constituted the majority of our cohort (72.6%), female was associated with less readmission odds, which was observed by Stolfo,et al.[23]in a prior study. In contrast to a prior study done using NRD,[20]blood loss anemia, packed red blood cells transfusion, and discharge to a nursing facility were not found to be independent predictors of readmission in nonagenarians. LOS greater than two days in index admission predicted readmission. This could be explained by the higher comorbidity burden in this age group. Our study demonstrated the strong impact of palliative care encounter on prevention of future readmission although it was poorly utilized (only 6.9% of our cohort received palliative care service). This finding could open avenues for palliative care utilization in this age group with emphasis on quality of life rather than quantity.

In-hospital mortality rate in index admission was 3.8% in our cohort, which is close to average mortality in hospitalized patients aged 75 years and higher(4.3%−4.6%).[24]

Compared to readmission predictors, chronic comorbidities such as cardiac arrhythmias, aortic stenosis, liver disease, pulmonary circulatory disorders,and CKD stage III or higher were independently associated with increased odds of in-hospital mortality.Interestingly, dyslipidemia and history of percutaneous coronary intervention were associated with lower odds of in-hospital mortality, which was thought to be due to prescribed statins and other goal-directed medical therapy for coronary artery disease. However, Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (The OPTIMIZE-HF) study on 48,612 hospitalized patients with acute HF showed similar results regarding hyperlipidemia despite that only 66% of patients diagnosed with hyperlipidemia were on statins or other lipid lowering therapy.[16]

Chronic comorbidities were also identified as predictors of increased LOS and total hospital charges such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic pulmonary disease. Blood transfusion was associated with increased LOS and increased total hospital charges, but it did not affect readmission nor inhospital mortality outcomes. Readmission within thirty days was more costly on average compared to index admission (mean cost: 43,265 USDvs.32,554 USD), which is likely due to increased LOS in the readmitted cohort (mean LOS: 5.46 daysvs.4.72 days).It is worth mentioning that discharge to nursing facilities was higher in the second admission compared to the index admission (0.32%vs.0.15%,P=0.29), which probably added to the overall health care cost.

LIMITATIONS

Our study has certain limitations. Firstly, NRD uses ICD codes for diagnosis, which is subject to coding errors. Secondly, the differentiation between volume overload due to HFpEF and advanced CKD can be challenging. Both conditions often co-exist,and we are unable to differentiate between the primary disease processes driving the hospitalization. The primary outcome of our study is the rate of thirty-day readmission post-discharge and inhospital mortality may be a competing risk endpoint, particularly in this age group, thus assessing the composite endpoint of thirty-day readmission or death would be an area of future research. We cannot identify patients who may have expired without being re-hospitalized in our database. The information pertaining to the longitudinal followup of patients, information related to race, ethnicity,individual operator, and procedure level is also not available in the NRD. Moreover, factors influencing patient prognosis such as medications and echocardiography findings such as diastolic grading are absent. Last but not least, the study was retrospective, which is subject to confounding bias not typically seen in prospective trials.

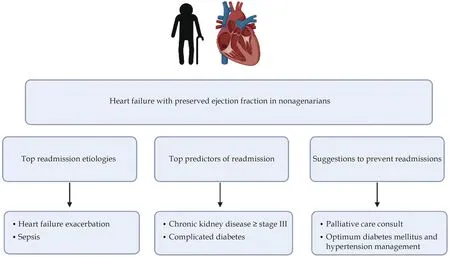

CONCLUSIONS

We identified several predictors of thirty-day readmissions, in-hospital mortality, increased LOS,and hospitalization cost amongst nonagenarians admitted with HFpEF. Having knowledge of these predictors should help guide further strategies targeting reduction of readmissions, decreasing healthcare costs, and improving the quality of care patients receive (Figure 2).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

All authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Figure 2 Central illustration.

杂志排行

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology的其它文章

- Echocardiography and impedance cardiography as determinants of successful slow levosimendan infusion in advanced older heart failure patients

- Association between serum cystatin C level and hemodynamically significant aortic stenosis: a prospective cohort study

- Lipoprotein(a) is associated with coronary atheroma progression:analysis from a serial coronary computed tomography angiography study

- A different cardiac resynchronization therapy technique might be needed in some patients with nonspecific intraventricular conduction disturbance pattern

- MiR-21-5p-expressing bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells alleviate myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by regulating the circRNA_0031672/miR-21-5p/programmed cell death protein 4 pathway

- Reversible heart failure in a patient with hypocalcemic cardiomyopathy