婺剧:浙中亮丽金名片

2021-06-24王晓明

王晓明

万年上山文化的发掘,表明浙江中西部是人类稻作文化最早的发源地,而婺剧就是这一文化成熟发展的一个标志与结晶。如今,它已成为浙江光彩夺目的金色名片和文化印记。

一

婺剧这个名称,一直到新中国成立之后才正式被叫响,过去长期称为“金华戏”,是流传在金衢一带六种戏曲声腔(即高腔、昆曲、乱弹、徽调、滩簧、时调)的合称。

姗姗来迟的名称后面,有着古老剧种非同寻常的500多年发展历程和绚烂光焰。

中国最早的戏曲形式“南戏”诞生于温州,作为温州通向广阔内地的关口,这些戏文早早就在金华的土地上回响。戈阳腔从西边涌进,昆腔从东边流入,徽调尾随徽商从北边南下,加上金华土生土长的表演形式——滩簧、时调,南腔北调在盆地里汇聚交融,一起热烈地唱响大地。

外来戏曲进入金华方言区,演员们便尝试着用本土方言演唱,在音乐上也逐渐向本地曲调靠拢。众多的南腔北调融汇贯通,竞争重组,优势互补,一种名为“三合班”,“二合半”的独特表演形式渐渐形成,一种特色独具的本地唱腔开始咿呀响起。

婺剧就这样在农耕文明的沃土上扎根萌芽,它很像一株顺水漂流的禾苗,乘着南来北往的文化溪流跨过山脉、越过江河。而一旦在丘陵上扎下根须,它就贪婪地汲取丰富的本土养分,汇拢四面八方各具特色的色泽音调,拔节分蘖,扬花吐穗,成长为本土艺术园地里饱满丰实的水稻。

二

在全国300多种至今仍在演出的戏曲剧种里,婺剧农民化、地域化特点独特且鲜明,它从来就是鱼米之乡生长的一棵稻穗,而不是庭院楼阁里养植的一株兰花。

“什么藤结什么瓜,什么人说什么话。”婺剧唱词里说的,全是本地农民爱听的话。字字入心、句句入耳,淋漓酣畅、心花怒放。

婺剧大小剧目500多个,不少是连台本戏。许多戏反映忠奸斗争,让爱憎分明的农民们时而看得热泪盈眶,时而恨得牙关咬碎。而更多的则是反映社会生活,一幅幅、一个个充满生活情趣的画面场景,洋溢着忠孝节义、尊老爱幼、扶正祛邪,见义勇为等中华优秀传统理念。

农民们天性纯朴善良、爱憎分明,因此要求情节故事无论如何曲折离奇,人物命运无论怎样大起大落,都一定要有“大团圆”结局。好人有好报,恶人遭天谴,皆大欢喜。那些欢笑和眼泪化作一粒粒善良种子,播撒进一代代观众的心田,成为他们今后评判事非、鉴别真伪、教育子女的自觉准绳。

稻米养育农民的肉体,婺剧培育农民的精神。

婺剧表演地点长期都在農村露天草台,或是庙宇祠堂。看台下熙熙攘攘,全是些布衣、农民和手工业者。这样的演出场合,势必逼迫演员努力去展现粗犷、夸张、浓烈,去载歌载舞、边唱边做、滚打摸爬,处处出戏而入戏。久而久之,形成了婺剧“文戏武做,武戏文做” 的鲜明特色,以及“大花过头,老生平耳,小生平肩,花旦平乳,小丑平脐”的特殊表演风格。

婺剧“文戏武做”的特点,突出地体现在《断桥》一折。在京剧和昆、越等剧种同名折子戏里,都是表现优雅细腻的感情戏。偏偏婺剧以强烈表现柔情,以粗犷反衬细腻,以高难度的武功表露人物细致的情感。戏高潮时大锣大鼓、跌宕起伏,演员满台飞舞,雷霆万钧里见侠骨柔情,剧烈冲撞中显情感真诚。因此,它在全国诸多同名戏曲中异军突起,被周恩来总理誉为“天下第一桥”。

不仅“文戏踏破台”,婺剧还 “武戏慢慢来”“一戏一招”,充满理性地处理“动与静”“粗与细”等艺术关系,不时在舞台上展现一幅幅极具雕塑感的画面,美感形式独特。

婺剧的许多动作直接来自生活,同时还保留许多古老傩戏、百戏、目莲戏的表演动作和程式,也因此被梅兰芳先生视为“京剧祖宗”,是许多专家学者眼里的戏曲 “活化石”。

婺剧最华美的部分,其实在于它的音乐,其中最为人称道的是从金华民歌中移植继承的那部分,如“小桃红”“三五七”,许多曲牌已是现代乐队在重大场合演出的保留曲目。

三

“三耕一闲”,当冬季雪花开始缓缓飘落,农家一年四季最闲适的时节随之来临。“咚咚锵锵”的婺剧锣鼓声这时格外响亮。

家传耕读,乘闲时扮作生旦净丑;

戏为君相,结局后仍是士农工商。

许多乡间戏迷自发聚集,你演花旦,我扮小生,你敲锣鼓,我拉二胡,一个个农民业余剧团锣鼓喧天地登场。剧本是现成的,曲调是固定的,演得好不好是一回事,但那份认真快乐全都写在一张张质朴的脸上。演得好的渐渐搭起固定班子,取个好听的名号叫 “品玉班”“文锦社”,或者“大连升班”“大荣华班”……从此踏上职业化道路,许多婺剧班社就这样自发聚集,逐渐成熟、走红。

四

“三熟丰收创历史,十月农闲戏一场”。

在几百年的漫长岁月里,看戏是乡间难得的社交良机,也是乡村又一个盛大的节日。虽然那些舞台简陋,不过是村口临时搭起的木台,或者宗族祠堂狭小的戏台,但只要消息传开,顿时举村欢腾,眼睛一眨,大小板凳已黑压压地拥成一片挤满场院。

演戏照例不舍昼夜;正午红日当空,“咚咚锵”锣鼓声照样响起。老人们一个个正襟危坐,抽着烟、喝着茶全神贯注,有的还摇头晃脑,一字不落地跟着台上哼唱。小伙子、大姑娘一边看戏,一边眉来眼去传递情愫。最忙乱的是那些半大的孩子,要么拥挤在台前,要么爬进后台,去偷看演员化妆、乐队弹弦。当夜色渐渐淹没村庄,锣鼓声便催波激浪,将欢乐推向高潮。

碰上“斗台”就更加热闹了。实力雄厚的村子会一次请来几个、乃至十几个剧团,同时搭起多个舞台遥遥相对,让众多剧团班社面对面一决高下。斗台开始,各剧团都排出最强阵容、演出最拿手剧目。演员们斗志昂扬,唱念做打一样也不马虎。

午夜十二点时,一声铳响宣告斗台结局,台下观众最多的剧团获胜,演员们披红挂彩、喜气洋洋。

有时,戏演到半途常常天降大雨,或者飘起雪花。但演员们唱得更加卖劲,观众们则看得更加着迷,在风雪雷电中坚持到宣告收场的锣鼓响起………

“农民看,农民演,演农民。”婺剧就这样像水稻一般生长了500年,是一个纯属乡间、纯属农民的“草根”剧种,在金衢稻作文化的沃土上郁郁葱葱。

五

新中国的成立不仅给了婺剧正式的名号,更让这株已似干涸的禾苗枯木逢春,再次显露非同异常的生命活力。1955年,省文化厅下文成立浙江婺剧团,一大批省艺校婺剧班科班出身的文化青年来到金华,和部分有志于戏剧改革的本地艺人一起,开启婺剧史上崭新的篇章。

一批文化人首次加入婺剧队伍,对许多传统剧目进行整理改编,创作出《僧尼会》《牡丹对课》等一批全新的剧本、曲谱,成为当代婺剧常演不衰的经典佳作。

新生的婺剧在人们眼前铺开一幅幅绚丽多彩的艺术画页。它在血火硝烟的历史中提炼出宝贵的红色基因,在成败得失的朝代更迭里探究岁月的灼见真理。它以全新的视角诠释人情人性,带给观众更多真善美之馨香而长久的回味。

在保留传统风格基础上,某些示范性剧团演出形态渐趋精致,发生了许多与时俱进的深刻变化。大红轿子里流水一般飘曳出身穿彩衣彩裤、扮相俊美的花旦,风摆杨柳一般移动着婀娜碎步。岁月在微微翘起的兰花指上轻轻一拨,飘向似桃花梨花纷飞般绚烂而舞如火如荼的华美舞台。

从徽调曲库中汲取了丰厚营养,从婉约昆腔上嫁接了淳美意象,从古代歌舞里遴选朝衣出水的艳美,当然更多的还是上山稻浪中蕴育的最初哪些音响……婺剧蘸着婺江清流洗去数百年的粗犷,优雅时尚地登上北京、上海的顶级舞台。1962年,浙江婺剧团晋京演出轰动京华,其间周恩来、朱德、陈毅等党和国家领导人多次观看演出,周总理还在家中亲切接见多位演员代表。

近70年来婺剧英才辈出,先后涌现出一大批有成就和影响的名角,从徐东福、周越先、徐汝英、周越桂,到郑兰香、吴光煜、严宗河、葛素云、朱云香、邵小春、苗嫩、刘智宏等,再到以陈美兰、张建敏、朱元昊、赵殊珠、周子清、黄维龙、郑丽芳、范红霞、吴淑娟、黄庆华等为代表的中年演员。如今,又涌现出了优秀青年演员杨霞云、楼胜、巫文玲、陈丽俐、陈建旭、李烜宇、周宏伟、张莹……

当改革开放的时代春风吹拂神州大地,婺剧迎难而上锐意改革,以崭新的姿态迈上中国戏曲最高水平的表演舞台,实现了自已更加辉煌的存在。一出出令人倾倒的婺剧精品征服着全国观众,《昆仑女》《梦断婺江》《铁血红颜》、青春版《穆桂英》、《血路芳华》《宫锦袍》《信仰的味道》《基石》……接二连三摘取着中国戏曲舞台上最为耀人眼目的奖项。

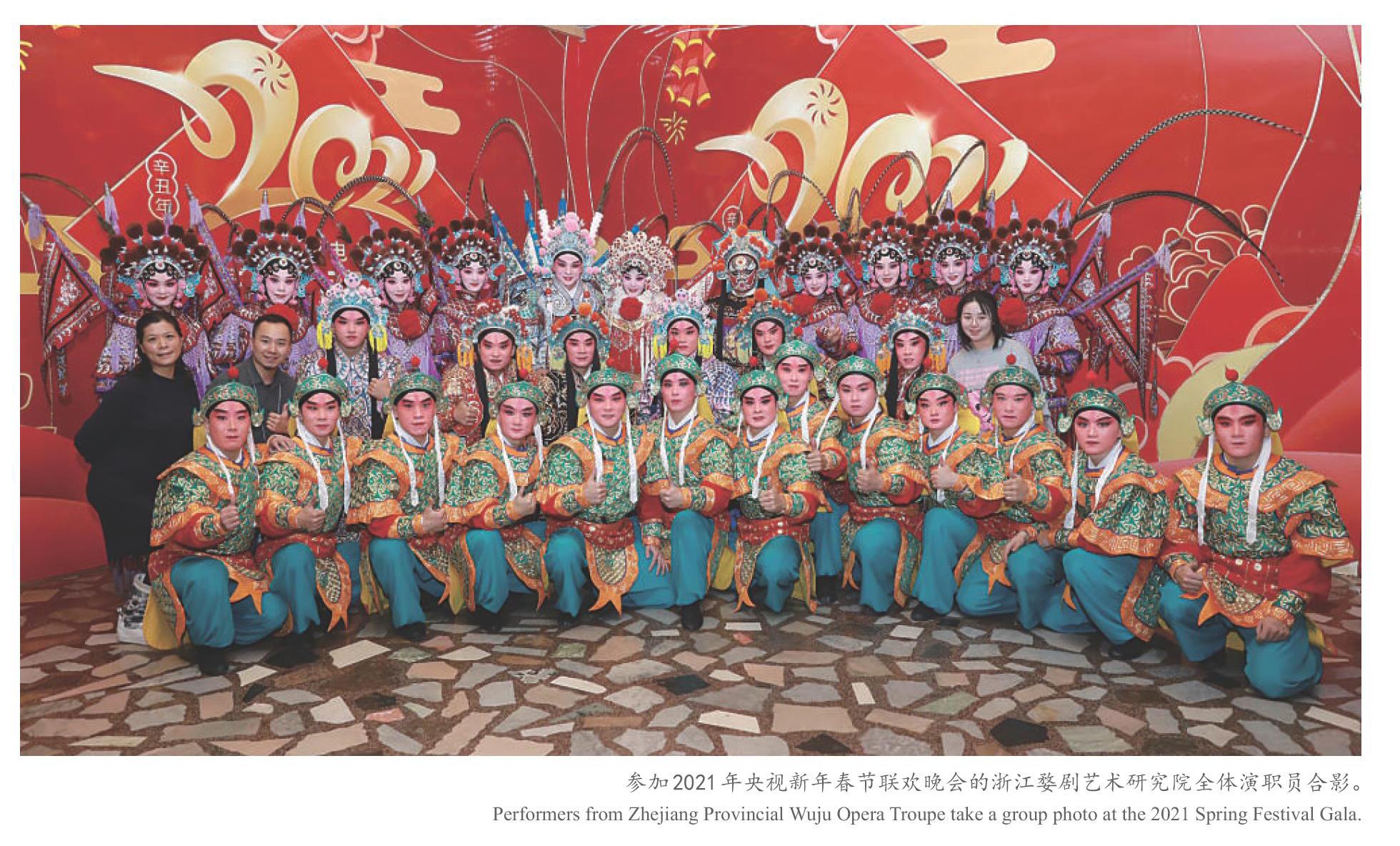

浙江婺剧艺术研究院组建的“陈美兰新剧目创作团队”,受国家委派和演出商邀请赴海外文化交流和商业演出,迄今已出访全球近50个国家和地区。婺剧六次在国家大剧院参加由中宣部、文化和旅游部主办的新年戏曲晚会,10次登上中共中央国务院春节团拜会、央视春节联欢晚会、央视元宵晚会等大舞台,已成为全国地方戏曲院团中唯一全面参与国家级最高规格演出的院团。

但在最熟悉、养育它的乡亲们眼里,婺剧仍然姓“农”,仍然像秋季成熟的水稻那样低低垂向大地母亲。尽管得奖无数、荣耀满身,浙江婺剧艺术研究院仍坚持围绕“农村、校园、社区”,每年公益演出达500余场,多次获得 “全国送戏下乡、服务农民先进集体”等荣誉称号。几十个婺剧民间职业剧团日夜奔走在乡间,为观众们送去乡味十足的演出。

2008年,婺剧入选“国家级非物质文化遗产”。

2013年,浙江婺剧艺术研究院入选首批全国地方戏创作演出重点院团。

2019年,浙江婺剧艺术研究院被金华市人民政府授予集体二等功。

時光渐渐老去,但在岁月舞台上摸爬滚打好几个世纪的婺剧却越来越年轻、越来越充满活力,像一株扬花吐穗500年却依然苍翠茁壮的禾苗那样茁壮生长,成为浙中文化最杰出的代表、最亮丽的名片和最重要的文化印记!

前方等待它的,依然会是一个个流金溢彩的丰收之果!

(作者系中国作家协会会员)

Wuju Opera: Zhejiangs Shining “Golden Card”

By Wang Xiaoming

While the archeological discoveries of the 10,000-year-old Shangshan Culture point to central and western Zhejiang as the earliest place for rice cultivation, Wuju opera was a crucial sign of the cultures maturity and its crystallization. Now it has become one of the most significant cultural symbols of Zhejiang.

Long known as “Jinhua xi” or “Jinhua theater”, the name Wuju wasnt widely circulated until after the founding of the Peoples Republic of China. Wuju opera is a collective name for six shengqiang or vocal tones, namely the high-pitched tune, the Kunqu opera tune, the Luantan (literally “random pluck”) tune, the Huiju opera tune, the Tanhuang (a local folk opera art) tune and the Shidiao (popular local ditties) tune, that have been historically popular in the areas of Jinhua as well as Quzhou.

Behind the medley of various vocal tunes and the late adoption of a more encompassing name lies the development history of the opera over the past 500 years. During the Song dynasty (960 -1279) in the 12th century, Nanxi (literally “southern theater”) was born in the Wenzhou area, the earliest form of Chinese opera. Close to Wenzhou and a gateway for Wenzhou people to reach inland, Jinhua was heavily influenced by Nanxi very early on. From the west, i.e. Jiangxi province, the high-pitched tune later came in, and from the east, i.e. Jiangsu province, Kunqu opera tune arrived. Then Huiju opera tune was introduced to Jinhua via Huishang (Anhui businessmen) from the north, before they were joined by the local Tanhuang and Shidiao tunes.

With so many “foreign” operas coming to Jinhua, performers there started to try singing the lines in local dialect and the opera music was also adapted to absorb more and more local folk melodies. Eventually, a unique local brand of opera emerged and took root in Jinhua.

Of the more than 300 operas that are still being actively performed in China today, Wuju opera is particularly noted for being a local and farmers opera, largely due to its rural origins. “The melons are whatever vines they grow on, and people utter whatever words befitting their upbringing,” a popular local saying goes. In Wuju opera, from script lines to music, from characters to stories, from costumes to body movements…everything has been tailored for the rural taste. Wuju opera has always been the sturdy rice plant growing in the paddy field, rather than the precious orchid nurtured and cultivated in a greenhouse.

In the plays, most of which center on the struggles between the loyal and the treacherous, the morals of the stories are straightforward and unambiguous. Farmers watching the operas love the heroes as much as they hate the villains. Traditional Chinese values, such as filial piety, faithfulness, righteousness, and respect for the elderly and care for the young, are regularly featured.

From the very beginning, the Wuju shows were mostly staged at outdoor venues-makeshift platforms in the open air, temples or ancestral halls, and with little to no help from any acoustic technologies, performers had no other way but to exaggerate their expressions, singing, body movements, costumes and even make-up. Apart from a set of formalized acting accumulated over time, many moves, poses and gestures came directly from real life, for which, Mei Lanfang (1894-1961), widely regarded as the greatest Peking opera master, called Wuju opera “the father of Peking opera”. To many experts and scholars of Chinese operas, it is the “living fossil of operas”.

The exaggerated performance was also in part the result of “popular demand”: in addition to clear-cut and distinct characters and morals, a happy ending is a must for farmer audiences. The good guys should be rewarded handsomely, and the bad buys should be punished severely. For the farmers, and many others indeed, all is well that only ends well.

In olden days, watching Wuju opera, usually during winter times when farm work was lighter, was a big occasion for rural residents, a festival in and of itself and a golden opportunity to do some socializing. As news of the upcoming shows reached a certain village, the whole village would already crowd around the temporarily propped up stage before you knew it. Once started, the shows would continue for days on end, day and night, rain or shine. In the audience, the elderly were often totally engrossed and even singing along, every single line in their heart; the young took any chances available exchanging love messages secretly; and the children clambered around the stage, trying to get a glimpse of the performers rehearsing or applying makeup.

The atmosphere would be even more boisterous if a “battle” happened to be on. In some richer villages, a few or even a dozen troupes would be invited to perform at the same time. Their stages only a stones throw away from each other, these troupes would field their best teams and plays, “battling” hard to win the audiences hearts. At midnight, the stage with the highest number of spectators won.

In fact, the farmers have been more than just spectators. Enthusiasts often organize themselves into amateur troupes, everyone playing an important part. Putting on a good performance is never the point; the point is to enjoy the process. Over the years, quite a number of those amateur performers and troupes turned into professionals.

For the past 70 years since the establishment of the Peoples Republic of China, ever more Wuju opera talents have been cultivated, traditional plays have been documented, compiled and new plays written, and professional Wuju opera troupes, the Zhejiang Provincial Wuju Opera Troup in particular, have gained national and even international recognition. In 2008, Wuju opera was duly included in the National List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of China.

Invigorated by governmental support and peoples renewed interest in traditional culture, Wuju opera is enjoying a renaissance. But to its rural roots it always returns. “For the farmers, by the farmers and into the farmers.” On the road ahead for Wuju opera, more bumper years beckon.