Breakthroughs and challenges in the management of pediatric viral hepatitis

2021-06-05EmanueleNicastroLorenzoNorsaAngeloDiGiorgioGiuseppeIndolfiLorenzoAntiga

Emanuele Nicastro, Lorenzo Norsa, Angelo Di Giorgio, Giuseppe Indolfi, Lorenzo D'Antiga

Abstract Chronic infections by hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) major causes of advanced liver disease and mortality worldwide. Although regarded as benign infections in children, their persistence through adulthood is undoubtedly of concern. Recent advances in HCV treatment have restored the visibility of these conditions and raised expectations for HBV treatment, which is currently far from being curative. Herein we describe direct-acting antivirals available for pediatric HCV (sofosbuvir/ledipasvir, sofosbuvir/velpatasvir, glecaprevir/pibrentasvir)and their real-world use. A critical review of the HBV pediatric classification is provided. Anti-HBV investigational compounds are reviewed in light of the pathophysiology in the pediatric population, including capsid assembly modulators, antigen secretion inhibitors, silencing RNAs, and immune modifiers.Recommendations for screening and management of immunosuppressed children or those with other risk factors or comorbidities are also summarized.

Key Words: Hepatitis C; Hepatitis B; Direct acting antivirals; Liver cirrhosis; Children

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization has estimated that - in 2015 - hepatitis B virus (HBV)and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections caused 1 .34 million deaths worldwide,exceeding the death toll of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and malaria and reaching that of tuberculosis[1 ]. These epidemics now move into the spotlight for the forthcoming innovations in their treatment armamentarium. We are living in the aftermath of the breakthrough of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) for HCV. Those drugs have radically changed the epidemiology of adult chronic liver disease in developed countries, but they are still poorly accessible in resource-limited settings,and their use in children is just beginning. Improvements in HBV treatment are just around the corner. Notably, most investigational compounds directed against HBV tackle the host immune response towards the virus.

The role of children in this scenario is very important. Treating children chronically infected by HBV and HCV is complementary to prevention of mother-to-child transmission, with the purpose of the epidemiological control. On the clinical side,treatments capable of restoring immune tolerance or exhaustion, and promoting viral clearance, are paramount to prevent advanced liver disease in adulthood. In this review, we identify and discuss the next challenges in treatment of pediatric viral hepatitis. Overcoming the barriers to the availability of treatment for all children is a major objective in HCV infection. Conversely, identifying homogeneous patients phenotypes of chronic infection, selecting timely and appropriate treatment, bearing in mind forthcoming therapeutic opportunities, are keys to meeting the current challenges in the management of pediatric HBV infection.

NATURAL HISTORY OF HCV INFECTION IN CHILDREN

HCV infection differs in children and adults in the mode of transmission, rate of clearance, progression of fibrosis, and duration of chronic infection when acquired at birth[2 ]. Vertical transmission of HCV from mother to child is reported to be the leading cause of pediatric infection worldwide. A recent review found that the risk of vertical HCV infection to the children of HCV antibody-positive and HCV-RNApositive women was 5 .8 % [95 % confidence interval (CI), 4 .2 -7 .8 ] for children of HIVnegative women and 10 .8 % (95 %CI, 7 .6 -15 .2 ) for children of HIV-positive women[3 ].

Symptomatic acute HCV is rare in childhood, but can present with lethargy, fever,and myalgia[4 ]. Approximately 20 %-25 % of acute HCV infections can be cleared spontaneously. Spontaneous clearance of the virus following vertical transmission is reported in around 20 % of infected patients, usually by 4 years of age[5 ]. Children who do not clear HCV spontaneously develop chronic infection that, is usually asymptomatic in pediatric patients[6 ]. During the chronic course, transaminase levels may be normal or intermittently elevated. Serum HCVRNA levels may considerably fluctuate as well, but without immediate prognostic relevance[7 ,8 ]. Histological findings are usually unremarkable, but the presence of cirrhosis is reported in 1 %-4 % of patients[7 ,9 ,10 ]. Overall, the risk of severe hepatic complications in pediatric patients is low[7 ].

Information on childhood to adult progression of liver is lacking, and the proportion of HCV-infected children who develop serious long-term liver disease is not clear[10 ]. Hepatic fibrosis is reported in less than 2 % of pediatric cases, but the percentage is much higher in patients with long-term follow-up, suggesting that the development of fibrosis correlates with age and the duration of infection[11 -14 ]. In a recent study from the United Kingdom including 1049 patients with a chronic hepatitis C acquired during childhood, one-third developed liver disease, with a median of 33 years after infection. Patients who acquired the infection vertically developed cirrhosis at an earlier age (36 years) compared with patients who acquired HCV in childhood through drug abuse (48 years), blood transfusion (46 years), or with an unknown route of infection (52 years, P < 0 .0001 ). In that cohort, the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was 5 %; 4 % required a liver transplant, and death occurred in 3 %[11 ]. Long-term liver complications included cirrhosis, HCC, or requirement for transplantation[11 ,12 ,14 ]. In adults, the natural history of chronic HCV infection is affected by associated medical and social factors including hepatic steatosis, alcohol consumption, malignancy, and viral HIV and HBV coinfection[11 ,15 ]. Extrahepatic manifestations of chronic HCV (e.g., positive nonorgan-specific autoantibodies,autoimmune thyroiditis, glomerulonephritis) are rare in children[15 ,16 ]. In conclusion,early acquired hepatitis C infection is a clinically and histologically silent condition.Nevertheless, it may become insidious. Although the percentage of children developing liver cirrhosis in adulthood is low, progression beyond the second decade of life is likely. Thus, the main aim of therapeutic interventions in pediatric patients is not the treatment of an ongoing liver disease, but the prevention of progression by early eradication of the infection[17 ].

THE BREAKTHROUGH OF DIRECT-ACTING ANTIVIRALS

In 2011 boceprevir and telaprevir, two first-generation NS3 /4 A protease inhibitors,were approved for use in combination with pegylated interferon (peg-IFN) and ribavirin for the treatment of adults with chronic HCV infection[18 ,19 ]. The response rates to triple therapy with boceprevir or telaprevir was improved when compared with dual therapy with peg-IFN and ribavirin, but was accompanied by significant side effects. Since then, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have approved 13 different DAAs and six fixeddose combinations for the treatment of adults with chronic HCV infection(sofosbuvir/ledipasvir, ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir, elbasvir/grazoprevir,glecaprevir/pibrentasvir, sofosbuvir/velpatasvir, and sofosbuvir/ velpatasvir/voxilaprevir)[20 ]. DAAs are classified into several categories by their molecular targets. Those agents were designed to inhibit specific viral proteins that have critical roles in HCV replication. They include NS3 /4 A protease inhibitors (e.g., simeprevir,paritaprevir, grazoprevir, voxilaprevir, and glecaprevir), nucleotide (e.g., sofosbuvir)and non-nucleotide (e.g., dasabuvir) inhibitors of NS5 B polymerase, and NS5 A inhibitors (e.g., daclatasvir, ledipasvir, ombitasvir, velpatasvir, elbasvir, and pibrentasvir). The development of combinations of DAAs is based on the concept that at least two drugs are needed to achieve the treatment goal of a virological response of> 95 %) without selecting resistant mutants. When the backbone of the treatment is a nucleoside NS5 B inhibitor like sofosbuvir, only one other drug, an NS3 /4 A protease inhibitor or a NS5 A-inhibitor, is usually required. Conversely, a non-nucleoside NS5 B inhibitor like dasabuvir should be used together with both NS3 /4 A proteases and NS5 A inhibitors.

The introduction of DAAs changed the HCV treatment paradigm. These regimens are oral, patient-friendly, have treatment schedules as short as 8 wk, are highly effective, and have few side effects. Given these clear advantages over IFN-based therapies, DAAs have become the preferred treatment for adults with HCV.Remarkably, the latest generation of DAAs (glecaprevir/pibrentasvir, sofosbuvir/velpatasvir, and sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir) have pan-genotypic activity,thus simplifying treatment decisions.

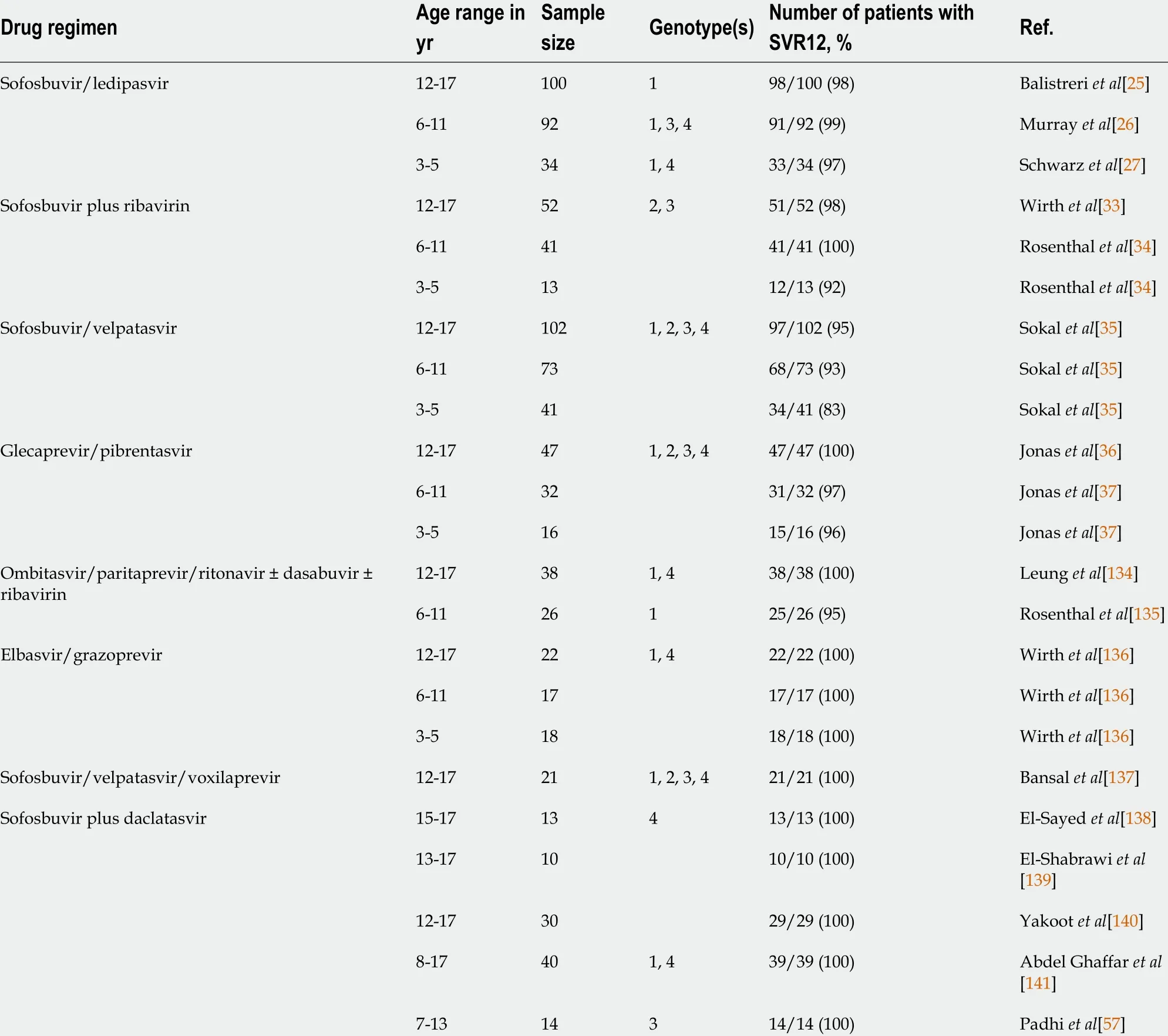

TREATING CHILDREN WITH HCV

IFN-based treatment regimens are no longer recommended as therapeutic options in adolescents and children with HCV, given the high toxicity and modest sustained virological response (SVR) rates[4 ,23 ,24 ]. In 2017 , the United States. FDA and the EMA approved the use of sofosbuvir/ledipasvir for adolescents 12 years of age or older with HCV genotype 1 , 4 , 5 , or 6 infection, and sofosbuvir in combination with ribavirin for those with HCV genotype 2 or 3 . Since then, four different regimens with agespecific limitations have been approved based on the results of four phase II-III, openlabel, multicenter, multicohort studies (Table 2 ).

Sofosbuvir/ledipasvir was tested in 100 adolescents 12 -17 years of age, 92 children 6 -11 years of age, and 34 toddlers 3 -5 years of age with chronic HCV infections[25 -27 ].The efficacy of the combination across the three different age cohorts was high(Table 1 ). One adolescent discontinued treatment and one did not attend posttreatment follow-up visits after having achieved the end-of-treatment response. One cirrhotic child 6 years of age with HCV genotype 1 a infection relapsed by the 4 -wk follow-up visit, and one 3 -year-old patient discontinued treatment after 5 days because of “abnormal drug taste” and vomiting. The treatment was well tolerated. No serious or grade 3 -4 drug-related adverse events were reported, and no patient discontinued treatment because of an adverse event. The efficacy of this combination has been confirmed in real-world studies[28 -32 ].

The combination of sofosbuvir and ribavirin was tested in 52 adolescents, 41 children 6 -11 years of age and 13 toddlers 3 -5 years of age with chronic HCV infection,showing high efficacy (Table 1 )[33 ,34 ]. One adolescent with HCV genotype 3 infection who did not achieve SVR 12 wk after the end of treatment (SVR12 ), was lost to followup after achieving the end-of-treatment response and SVR4 (HCV-RNA negative 4 wk after the end of treatment). In the younger cohorts, a 4 -year-old child who did not achieve the primary endpoint of SVR12 discontinued treatment after 3 d because of an“abnormal drug taste”. No patients had a virologic nonresponse, breakthrough, or relapse. Treatment was well tolerated. One serious adverse event, accidental ribavirin overdose requiring hospitalization for monitoring was reported in a 3 -year-old patient.The child completed treatment and achieved SVR12 .

A sofosbuvir/velpatasvir fixed-dose formulation was tested in 102 adolescents and 73 children 6 -11 years of age with chronic HCV infection[35 ]. Two treatment failures were reported, a 17 -year-old girl with genotype 1 a who became pregnant and discontinued therapy at week 4 , and a 10 -year-old girl with genotype 1 a. Eight patients were lost to follow-up. The treatment was well tolerated. No serious or grade 3 -4 drugrelated adverse events were reported, and no patient discontinued treatment because of an adverse event. The combination of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir was tested in 47 adolescents[36 ], and an SVR12 of 100 % was reported. No patients had virologic nonresponse, breakthrough infection, or relapse. The treatment was well tolerated. No serious adverse events were reported, and no patient discontinued treatment because of an adverse event.

Sofosbuvir/ledipasvir and sofosbuvir plus ribavirin are approved for children as young as 3 years of age. Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir and glecaprevir/pibrentasvir are approved for those older than 6 years older than 12 years of age, respectively. The results of the trials of those regimens for younger age cohorts (3 -5 years of age for sofosbuvir/velpatasvir and 3 -11 years of age for glecaprevir/pibrentasvir) are now available[35 ,37 ], and expansion of the indication is expected in late 2021 . Remarkably,adherence to the treatment regimen seems to be the main factor impacting the effectiveness of DAA regimens. Noncompliance was responsible of most of the treatment failures across the different trials[22 ].

REAL-WORLD USE OF DAA IN CHILDREN

After the approval of DAAs by international regulatory agencies and their inclusion in clinical guidelines in the early 2010 ’s, other barriers had to be overcome before they actually became available. In the adult setting, delay in private third-party payer authorization was an obstacle to access to DAA[38 ,39 ]. In the pediatric setting, the situation is paradoxical. DAA treatment has been approved by the EMA and the FDA,but the drugs are not available in many countries because of a lack of indicationsapproved by the national agencies[40 ]. Nevertheless, eradicating HCV infection in early life has been demonstrated to impact favorably on the quality of life and to be cost-effective[41 ,42 ]. In fact, reports of real-world experience with the pediatric use of DAAs are increasing, and have shown that the excellent results of the experimental trials can be replicated in adolescents. A study in a cohort of 78 Italian children 12 -17 years of age with chronic genotype 1 , 3 , and 4 HCV infections treated with sofosbuvir/ledipasvir had an SVR12 of 98 .7 %[28 ]. Similar results were obtained in three cohorts of Egyptian children. Thirty adolescents with genotype 2 and 144 with genotype 3 infections achieved 99 %-100 % SVR12 s[31 ,32 ], and 20 children 6 -12 years of age had an SVR12 of 95 % after fixed half-dose sofosbuvir/ledipasvir, with only one patient lost to follow-up[43 ]. Real-world experience has also confirmed that children are ideal candidates for a shortened DAA course, as they typically exhibit little or no fibrosis. In fact, noncirrhotic, treatment-naïve children with genotype 1 and 4 infections and low viremia below 6 .8 log10 IU/mL HCV-RNA have been reported to achieve 100 % SVR12 after only 8 wk of sofosbuvir/ledipasvir[29 ,44 ].

26. A room with six little beds: While the room has six beds, it is not intended for the six brothers who will be in human form for only 15 minutes, barely the length of a catnap.Return to place in story.

Table 1 Pediatric studies of different combinations of direct-acting antivirals

HCV TREATMENT OF HCV IN CHILDREN AT RISK

The advent of DAA has radically changed the approach to HCV eradication treatmentnot only for otherwise healthy children but also for those with comorbidities. The high safety profile of DAA fostered wide experimental use for previously neglected clinical conditions for which IFN-based treatment strategy was proscribed[45 ]. HCV recurrence after LT is a well-known problem in the adult setting, and can progress rapidly to graft cirrhosis and early loss[46 ]. HCV eradication with DAA before and after LT brought a tremendous improvement in transplantation outcomes[47 -49 ]. The type of post-LT immunosuppression regimen seems not to impact the DAA treatment response[50 ], but fluctuation of calcineurin inhibitor trough levels during treatment may account for graft immune-mediated dysfunction[51 ,52 ]. Although a similar DAA efficacy might be expected in pediatric LT recipients, no relevant pediatric experience has been published.

Table 2 Direct-acting antiviral regimens approved for treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in children and adolescents

So far only seven children receiving DAAs after hemopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) for hematological disease have been described in the literature. One had received HSCT for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (4 years of age, genotype 1 a)[53 ], and another for sickle cell disease (15 -year-old, genotype 4 )[54 ], and were treated with a combination of sofosbuvir/simeprevir for 24 wk and 12 wk, respectively. They achieved stable viral clearance with calcineurin inhibitor-based regimens (cyclosporin+ mycophenolate mofetil, and tacrolimus + sirolimus, respectively). The other five children were 5 -12 years of age, and received haploidentical allogeneic HSCT for genotype 1 b refractory lymphoblastic leukemia, and were under cyclosporin maintenance[55 ]. All of them were treated with 24 wk of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir after a median HSCT follow-up of 15 mo, and achieved SVR by 1 mo. El-Shabrawi et al[56 ]reported on a 12 -wk course of sofosbuvir/daclatasvir in 20 genotype 4 -infected children in full remission of a hematological malignancy for more than 18 mo. All patients achieved SVR24 without notable adverse events. Two teams of researchers have reported on DAA-driven HCV eradication in thalassemic patients. In total, 25 children were enrolled, 14 with genotype 3 received 12 -wk sofosbuvir/daclatasvir and 11 with genotype 4 received 12 -wk sofosbuvir/ledipasvir). All achieved SVR12 without complaining of any serious adverse reactions[57 ,58 ].

Due to their efficacy and safety profile, DAA use is expanding to cutting-edge therapeutic scenarios. Hematopoietic stem cell-gene therapy (HSC-GT)—a life-saving option for inborn error diseases—is contraindicated in HCV-infected children because of the infection risk of bone marrow cells used as starting material for the manufacture. A 12 -wk course with sofosbuvir/ledipasvir was found to allow autologous HSC-GT for the correction of severe combined immunodeficiency caused by adenosine deaminase deficiency as described in a pioneering study[59 ]. Pediatric studies have not yet replicated the encouraging results with DAA in adults with HIV/HCV coinfection[60 -62 ], even when vertically transmitted[63 ], nor for the treatment of HCV in hemodialyzed[64 ] and kidney transplant patients[65 ,66 ].

NATURAL HISTORY OF HBV IN CHILDREN

Similar to HCV, childhood HBV infections occur mostly by mother-to-child transmission. In highly endemic countries, up to one third of the HBV incident transmissions are horizontal, caused by child-to-child, household or intrafamilial contacts[67 ]. Unlike adults, the prevalence of HBV infections in children reflects the extent of infant and HBV vaccination at birth, which is done with the goal of eradication in the absence of an effective antiviral treatment[68 ]. According to the last World Health Organization hepatitis report, global hepatitis B surface antigen(HBsAg) prevalence in preschool children dropped from approximately 4 .7 % between the 1980 and the early 2000 s to 1 .3 % in 2015 , following the widespread adoption of universal infant immunization[69 ]. The age at transmission determines the development of chronic HBV infection, which occurs in approximately 90 % of infected newborns and infants compared with only 10 % of infections acquired later in childhood or in adults[70 ,71 ]. Once chronic infection is established, the subsequent disease progression is the result of the adaptive immune response to HBV, immuneinflammatory liver injury, and the pathogen itself.

Until recently, patients have been classified by immune activity and control criteria,assuming that the clinical phenotype of HBV infection represented a clear-cut immunological state. Due to the lack of immunological data, the latest classification by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) replaces states with“phases”, which focused more on the infection course in adults, but do not fit the pediatric scenario[72 ]. In fact, the natural history of chronic HBV infection across all ages has been described by few large, long-term, prospective studies[73 -80 ]. After infection, the vast majority of children enter a state characterized by detectable HBsAg and hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), high viremia, and normal or near-normal transaminase levels. This “tolerant” phase can last for decades, and Asian children or those carrying genotypes C or D have a higher likelihood to remain so[81 -83 ]. Eventually, at a median age of 30 years, 3 %-6 % of the patients achieve HBeAg/hepatitis B e antibody(HBeAb) seroconversion annually, and most of those patients succeed in suppressing viremia[73 ,75 ,81 ,82 ]. Spontaneous HBsAg/hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb)seroconversion, which potentially allows long-term infection control, rarely occurs,with a rate of approximately 0 .5 %/year[73 ,75 ].

The major concern in children with chronic pediatric HBV infection is the risk of cirrhosis and HCC, which occur in 1 %-5 % and 0 .03 %-2 % of the patients,respectively[73 ,74 ]. As this risk increases in parallel with the activity and the duration of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) (e.g., transaminase elevation in the presence of elevated viral load)[84 ], the ultimate long-term goal is the achievement of sustained viral suppression, either as a result of the immunologic control or with the use of antiviral drugs.

PHENOTYPE CHARACTERIZATION OF CHILDREN WITH CHRONIC HBV INFECTION

The current classification of chronic HBV infection recognizes different phases and considers their interchangeability[72 ]. The phases are identified by the presence or absence of HBeAg (i.e.HBeAg positive and HBeAg negative) and by increased transaminases, which distinguishes chronic hepatitis from chronic infection. These categories do not fit the pediatric scenario well, where HBeAg-positive chronic infection tends to persist and HBeAg-negative hepatitis is anecdotal[85 ].

Classifying patients with HBV infection by the clinical phenotype, which reflects the immune status against the virus, has some advantages. Phenotype classification has been progressively refined to harmonize population data, estimate the need for antiviral treatment, and possibly predict the outcome of the infection[81 ,82 ]. It describes three childhood phenotypes: (1 ) immune-active (HBeAg +/-, elevated transaminases, HBV-DNA > log104 IU/mL); (2 ) immune-tolerant (HBeAg-positive,normal transaminases, HBV-DNA > log104 IU/mL); and (3 ) inactive carriers (HBeAg+/-, normal transaminases, HBV-DNA ≤ log104 IU/mL); with the remaining being“indeterminant”[81 -83 ]. So defined, the immune phenotype may help predict the fate towards infection control. Indeed, HBeAg-positive immune-active children are much more likely to achieve spontaneous HBeAg/HBeAb seroconversion (28 % and 7 .47 %/year) compared with immune-tolerant children (11 % and 2 .29 %/year)[81 ]. In a scenario characterized by the lack of clear treatment indications, and disappointing therapeutic outcomes, the definition of phenotypes has proven to bear prognostic value, and to help define homogeneous groups for patient selection in future trials.

CONTROVERSIES IN THE TREATMENT OF CHILDREN WITH HBV

The current pediatric guidelines recommend limiting treatment to children with prolonged (> 6 mo) active hepatitis B and evidence of fibrosis, and to observe those with the immune-tolerant phenotype[86 ]. The rationale for this approach, is that HBeAg-positive CHB, especially when protracted and beginning early, at < 3 years of age, has the highest risk of progression to cirrhosis, which is between 1 % and 5 % by the third decade[73 ,74 ]. Many centers tend to delay treatment based on the sound conception that CHB is harmless and that transaminase activity heralds spontaneous immune clearance[73 ]. Moreover, there is evidence that treatment only accelerates HBeAg/HBeAb seroconversion without influencing the proportion of patients who seroconvert over time[75 ]. On the other hand, treatment could be indicated to break tolerance. The EASL recommends nucleoside or nucleotide analogues (NAs) for longterm viral suppression in immune-tolerant patients 30 years of age or older[72 ], to reduce the risk of fibrosis and cirrhosis in those with delayed immune clearance[87 ,88 ]. In fact, studies highlight that high viremia in persistently HBeAg-positive patients is associated with the highest risk of cirrhosis, HCC, and liver-related mortality and that functional infection control following HBeAg/HBeAb seroconversion lowers those risks[87 ,89 ,90 ]. Thus, the question has arisen whether treatment should also be offered to immune-tolerant children.

The pediatric age has been regarded as a good time window to break viral tolerance.The first encouraging experience of treating immune-tolerant children was published in 2006 . HBV-DNA clearance and HBsAg/HBsAb seroconversion were achieved in 5 of 22 children (23 %) after 10 mo of sequential combination therapy with lamivudine and IFN-a[91 ]. That result was confirmed in a case-control study in which 6 of 22 immune-tolerant children achieved HBsAb-dependent functional control[92 ]. Another study reported a success rate of 33 %[93 ]. Those studies reported rates of HBsAb seroconversion of 20 %-25 %. Conversely, a clinical trial using a combination of entecavir and peg-IFN-a 2 a resulted in only 2 of 60 children achieving the primary endpoint of HBeAg loss and sustained HBV-DNA levels < 1000 IU/mL), with adverse events reported in more than 50 % of the children[94 ].

In favor of treating immune-tolerant children is evidence that their spontaneous seroconversion rate is much lower than that seen in adults[87 ]. Also, immune-tolerant children treated with a combination of lamivudine and IFN achieved a high rate of loss of HBsAg. Moreover, unlike adults, immune tolerance in young patients is characterized by a high level of HBV DNA integration and clonal hepatocyte expansion with malignant potential despite a relatively preserved anti-HBV T-cell response[95 ].Several new compounds in the pipeline that aim at increasing immune responses and overcoming immune exhaustion, with probably play a role in this specific group of children.

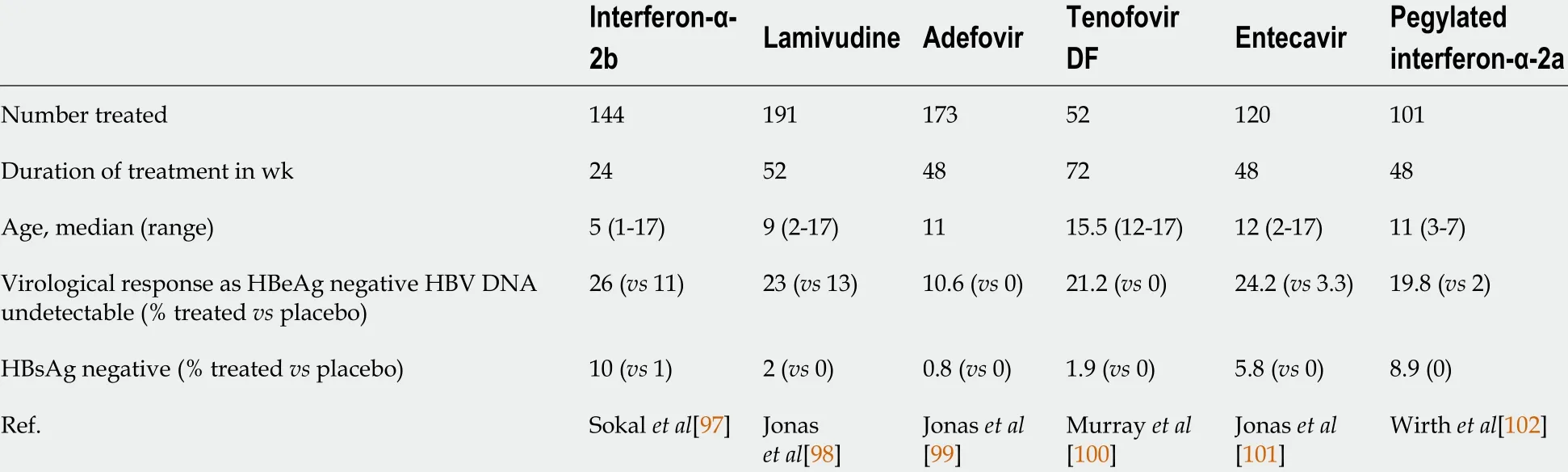

DRUGS APPROVED FOR CHILDREN WITH CHB

Seven different drugs have been approved for children and adolescents with chronic HBV infection by the United States FDA and the EMA (Table 3 ). IFN- and peg-IFN- are immune modulators that can be administered for a predefined duration with the aim of inducing immune-mediated control of HBV infection and achieving long-lasting suppression of off-treatment viral replication[68 ]. NA are potent HBV inhibitors that are used as long-term oral treatments to suppress viral replication, or as treatments of finite duration with or without IFN, to obtain a sustained off-treatment virological response. NAs are also classified as genetic barriers to resistance by the threshold of mutations required for clinically meaningful loss of drug susceptibility. Lamivudine,adefovir, and telbivudine have low and tenofovir, and entecavir have high, genetic barriers to resistance[68 ]. Treatment is indicated for children and adolescents withactive viral replication (detectable HBV-DNA levels), prolonged (6 -12 mo) active hepatitis (elevated serum transaminase levels) and/or inflammation or fibrosis on liver biopsy. Unless within a clinical trial, treatment is contraindicated when transaminases are normal[72 ,86 ,96 ].

Table 3 Antiviral drugs approved for adolescents and children with chronic hepatitis B virus infection

IFN--2 b, peg-IFN--2 a, lamivudine, adefovir, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, and entecavir were approved for the treatment of children and adolescents with chronic HBV infection following six randomized placebo-controlled trials[97 -102 ]. Tenofovir alafenamide was approved on the basis of studies of its use in HIV infection (Table 4 ).IFN therapy may be associated with higher rates of HBsAg loss compared with NAs.In all studies, a good overall treatment response defined by reduction of serum HBVDNA to undetectable concentrations, loss of serum HBeAg, and normalization of transaminases, was associated with and increased baseline histology activity index score, increased baseline transaminase concentrations, and decreased baseline HBVDNA concentrations.

Peg-IFN, entecavir, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate are considered the drugs of choice for the treatment of CHB in children by the major international societies[72 ,86 ,96 ]. The advantages of IFN and peg-IFN use in children, compared with NAs,are the absence of viral resistance and a predictable, finite duration of treatment.However, the use of IFN and peg-IFN is demanding for children because it requires subcutaneous injection and is associated with a nearly certain occurrence of flu-like symptoms.

DRUGS IN THE PIPELINE: RELEVANCE TO PEDIATRIC AGE

Currently available drugs against HBV have inherent limitations. NAs are safe and well tolerated and usually succeed in suppressing replication. They are not curative, as they act at a late stage of the viral cycle and do not prevent HBV-DNA persistence in episomal or integrated forms[96 ]. On the other hand, IFNs have limited efficacy and frequent side effects, but they are the most likely to achieve a definite “functional”cure with HBeAg or HBsAg loss, seroconversion, normal transaminases, and undetectable viremia)[103 ]. Various new classes of compounds are under investigation with the aim of achieving high rates of HBsAg seroconversion[104 ]. The candidate drugs are relevant to the pediatric field, as almost all act as immune modifiers to achieve tolerance breakthrough. The molecules currently in phase II and later trials are listed and summarized in Table 5 .

Capsid assembly inhibitors are antiviral agents complementary to NAs. JNJ-56136379 is an oral compound with two distinct mechanisms, the inhibition of the encapsidation of the pregenomic RNA (pgRNA) and the formation of covalently closed circular (ccc)DNA. It has been studied in 57 subjects with CHB treated for 28 d.HBV-DNA and HBV-RNA decreased at all tested doses and HBV-DNA was undetectable at the end of the study in one third of the patients. Nonetheless, none achieved HBsAg/HBsAb seroconversion[105 ]. ABI-H0731 (Vebicorvir) is an oralcompound inhibiting encapsidation, binding the core protein, and thus blocking the packaging of pgRNA into nucleocapsids. A phase I study conducted in healthy volunteers and 38 patients with CHB reported good tolerability and a prompt but temporary drop in viremia[106 ]. Two phase II studies are ongoing, whose interim results show that in already NA-suppressed patients, the addition of Vebicorvir significantly suppressed HBV-RNA levels. In treatment-naïve patients, its association with standard care resulted in a greater decrease in HBV DNA levels[107 ].

Table 4 Summary of results of clinical trials of hepatitis B antiviral therapy in children

Table 5 Investigational drugs for chronic hepatitis B infection

Nucleic acid polymeric secretion inhibitors reduce the release of HBsAg small viral particles, considered crucial in immune system exhaustion, thus favoring HBsAg loss and the seroconversion to HBsAb. The polymer REP-2139 , administered intravenously once weekly, has been selected for its tolerability within this class[108 ]. The sequential use of REP-2139 and peg-IFN-a in chronic HBV/HDV coinfection over a period of 63 wk, resulted in sustained HBsAg loss and seroconversion to HBsAb in six of 12 patients. HBV-DNA and HDV-RNA were negative in seven of the patients at the end of the treatment and in nine after 1 year of follow-up[109 ]. In HBeAg-negative CHB,REP-2139 or its analogue REP-2165 were used in combination with tenofovir and peg-IFN-a and achieved sustained HBsAg/HBsAb seroconversion in 41 % of the patients and functional control (undetectable HBV-DNA and normal transaminases) in 77 %, an unprecedented result[110 ].

RNA interference is another promising strategy that aims at silencing the translation of viral transcripts and subsequently decreasing HBsAg. Preliminary reports of efficacy are available from ongoing phase I/II studies on CHB entailing 3 moly administration of the small interfering (si)RNA JNJ-3989 (ARO-HBV). Regardless of HBeAg status and previous treatment, HBsAg decreased by 97 %-100 % after one dose and the majority of participants achieved HBsAg loss and dramatically reduced HBVDNA shortly after protocol completion[111 ,112 ]. This drug aims at breaking the immune stall toward the virus, as suggested by an ongoing trial in immune-tolerant adults. Similar interim results have been reported in a trial of the siRNA VIR-2218 [113 ].

Immune modulators are a heterogeneous class of candidate antivirals that target different effectors of innate immunity. Inarigivir is an RIG-1 pattern recognition receptor agonist, whose binding activates the IFN-I response. Final results of the phase II ACHIEVE trial demonstrated dose-dependent HBV-DNA reduction after inarigivir monotherapy, and the endpoint of an HBsAg reduction > 0 .5 log10 was achieved in 22 %of the patients[114 ]. Selgantolimod (formerly GS-9688 ), is a potent, orally administered Toll-like-receptor (TLR8 ) agonist capable of inducing tumor necrosis factor-, IFN-γ,interleukin (IL)-12 , and IL-18 expression[115 ]. Interim results of a phase II study show that it induced a significant HBsAg reduction in 16 %-30 % of CHB patients and occasional HBsAg loss 24 wk after treatment onset[116 ]. Bulevirtide is the only viralentry inhibitor approved by the EMA in 2020 for HBV/HDV coinfection, while it is on a phase II study for HBeAg-negative CHB (NCT02881008 ). It binds sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) to prevent HBV from entering hepatocytes. Combined with peg-IFN-a, it was shown to significantly decrease HBVDNA and HDV-DNA compared with peg-IFN-a alone[117 ,118 ]. Figure 1 depicts the different mechanisms of action of the HBV investigational products. Although many steps remain to achieve availability in the pediatric population, these drugs will certainly change the burden of HBV in children as much as in adults. The perspective of feasible and curative treatments aiming to break tolerance will increase the efforts to eradicate HBV early in life.

SCREENING AND TREATMENT OF HBV IN CHILDREN AT RISK

Data on the risk of hepatitis B reactivation in children who need to start immunosuppressive treatment for concomitant diseases are extremely scarce. For that reason, the recommendations expressed in a recent position paper of the Hepatology committee of the ESPGHAN[119 ] are mostly derived from adult evidence[72 ,96 ,120 ]. Experts recommend HBV screening, with HBsAg, HBsAb, and hepatitis B core antibody(HBcAb) testing, of all patients at risk of HBV reactivation, including those who are going to start immunosuppressive treatment. The tests should be performed even if HBV vaccination is complete, because, as shown in inflammatory bowel diseases,immunosuppressed children have low serologic protection from childhood vaccines[121 ]. Patients with negative HBV screening should be vaccinated before starting immunosuppressive treatment. This statement was supported by a recent study of 580 children that demonstrated a high seroconversion rate after the vaccine booster even after immunosuppression initiation[122 ].

Reactivation risk is classified as mild, moderate, or severe depending on the administered immunosuppressive agents[119 ]. The risk classes are based exclusively on adult evidence, as no corresponding pediatric study results have been published.Children scheduled for moderate or high-risk drugs should start antiviral prophylaxis,while a preemptive approach is preferred for children starting on low-risk drugs[123 ,124 ]. Even in the absence of pediatric evidence, a robust network metaanalysis reported that entecavir or tenofovir should be preferred for HBV reactivation treatment in immunosuppressed patients[125 ].

Figure 1 Novel investigational approaches to chronic hepatitis. cccDNA: Covalently closed circular DNA; DNA-: Negative-sense DNA filament synthesis;DNA+: Positive-sense DNA filament synthesis; EGFR: Epidermal growth factor receptor; NTCP: Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide; HBcAg: Hepatitis B core antigen; HBeAg: Hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen; NAPs: Nucleic acid polymers; pgRNA: Pregenomic RNA; preC RNA: Pre-core RNA;PRR: Pattern recognition receptor; rcDNA: Relaxed circular DNA; SVP: Small viral particle; TLR: Toll-like receptor.

Currently, reactivation of HBV infection in pediatric solid organ transplant recipients is anecdotal, as HBcAb-positive donors are almost no longer used, and endstage liver disease in HBsAg-positive recipients is exceptional. However, current recommendations replicate those for adults. In HBsAg-positive recipients, tenofovir or entecavir treatment should be started as soon as possible before transplant to achieve undetectable HBV-DNA[72 ,96 ]. NA treatment should be continued indefinitely, and HBV-specific immunoglobulins can be stopped after 5 -7 d, unless there is a history of drug resistance or poor compliance[72 ,96 ,126 ]. The use of grafts from HBcAb positive/HBsAg negative donors might be acceptable in case of organ shortage and in highly endemic countries. In those situations, recipients with HBsAb titers > 200 IU/mL might be protected from infection. However, ultimately the overall risk of developing infection depends on multiple factors and implies that recipients of such organs receive NAs (e.g., entecavir, tenofovir, or tenofovir alafenamide) for at least 1 year after transplant. Discontinuation might then be carefully evaluated on a case-bycase basis in HBsAb-positive children[127 ].

Another challenge for HBV treatment is represented by HBeAg-negative CHB,which is the most prevalent chronic hepatitis in many countries[128 ]. In adults, the clinical profile is characterized by wide fluctuations in viral replication and biochemical activity, with temporary spontaneous remissions[129 ]. The risk of cirrhosis in HBeAg-negative CHB is higher (8 %-10 %/year) than in HBeAg-positive(2 %-5 %/year)[130 ,131 ]. Infants with fulminant hepatitis caused by mother-to-child transmission of HBV e-minus variants are described[132 ]. This behavior is thought to result from absence of the tolerogenic effect of HBeAg. Adults are treated with long courses of NAs[133 ], but evidence of the benefits in children with HBeAg-negative hepatitis is lacking. However, pediatric HBeAg-negative and HBeAg-positive CHB have the same therapeutic approach, which is based on IFN- and indefinite use of NAs. The target should be decrease in HBsAg, HBV-DNA clearance, and normalization of transaminases.

CONCLUSION

HBV and HCV infections in childhood usually progress to chronic hepatitis through different mechanisms of immune tolerance and exhaustion. For HCV infection,different combinations of DAAs are increasingly available, including pan-genotypic combinations, with very few side effects and extremely high SVRs. For HBV infection,recent cohort studies have clarified that several factors including immune host phenotype, viral genotype, and ethnicity, contribute to spontaneous control. Viral hepatitis should not be a barrier to the use of immunosuppressive medications in the treatment of autoimmune conditions, nor to antineoplastic chemotherapy, provided that timely screening and appropriate pharmacological interventions are performed.Finally, new drugs in development for the treatment of HBV, mostly acting by fostering the breaking of tolerance, could dramatically improve the treatment outcome of CHB in children.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Deep learning for diagnosis of precancerous lesions in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: A review

- State of machine and deep learning in histopathological applications in digestive diseases

- COVID-19 in normal, diseased and transplanted liver

- Upregulation of long noncoding RNA W42 promotes tumor development by binding with DBN1 in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Development and validation of a prognostic model for patients with hepatorenal syndrome: A retrospective cohort study

- Inflammatory bowel disease in Tuzla Canton, Bosnia-Herzegovina: A prospective 10 -year follow-up