Asymptomatic portal vein aneurysm:Three case reports

2021-05-08

Kateryna Priadko,Marco Romano,Luigi Maria Vitale,Marco Niosi,Ilario De Sio,Department of Precision Medicine and Hepato-Gastroenterology Unit,University Hospital and Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli,Naples 80138,Italy

Abstract BACKGROUND Portal vein aneurysm (PVA) is an uncommon vascular dilatation,showing no clear trend in sex or age predominance. Due to the low number of published cases and the lack of management guidelines,treatment of this condition remains a clinical challenge.CASE SUMMARY We present three cases of asymptomatic PVA; the first and second involve an extrahepatic manifestation,of 48 mm and 42.3 mm diameter respectively,and the third involves an intrahepatic PVA of 27 mm. All were diagnosed incidentally during routine check-up,upon ultrasonography scan. Since all patients were asymptomatic,a conservative treatment strategy was chosen. Follow-up imaging demonstrated no progression in the aneurysm dimension for any case.CONCLUSION As PVA remains asymptomatic in many cases,recognition of its imaging features is key to favourable outcomes.

Key Words: Extrahepatic portal vein aneurysm; Intrahepatic portal vein aneurysm;Asymptomatic; Ultrasonography imaging; Colour Doppler; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Portal vein aneurysm (PVA) is a vascular malformation that is rarely diagnosed but,if complications occur,can be life-threatening. The estimated number of reported cases is low,at approximately 200[1]. PVA is defined as a portal vein diameter exceeding 19 mm in cirrhotic patients and 15 mm in normal liver[1]and can be either congenital (due to vascular anomalies) or acquired (mostly due to cirrhosis and/or portal hypertension,that are present in approximately 28.0%-30.8% of cases)[2,3]. Several systematic reviews did not identify any sex-related predisposition[1,2]. Notably,among portal venous system aneurysms,those in the main extrahepatic portal vein appear to be the commonest[2]. The average mortality rate is 10% and this mostly involves patients who have undergone liver transplantation[2,4]. Incidental discovery of asymptomatic aneurysms normally occurs through abdominal imaging,such as with computed tomography (CT),magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),or ultrasonography.

The clinical management of PVA ranges from conservative follow-up,that lasts years,to surgical intervention,depending on the presence or absence of symptoms and complications,such as rupture,thrombosis and compression of adjacent organs[1,2].

In this article,we present clinical cases of three asymptomatic patients in whom PVA was an incidental finding. The clinical cases are accompanied by ultrasonography,CT and MRI images of asymptomatic extrahepatic PVAs and ultrasonographic images of intrahepatic PVA. We also provide a review of the relevant literature to advance the knowledge on this underdiagnosed condition.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

Three patients,81-year-old male,52-year-old female and 73-year-old male respectively,presented to the outpatient clinic of our Unit of Diagnostic and Interventional Ultrasonography (Medical Center of the University Vanvitelli in Naples,Italy) for routine check-up for various pre-existing health issues.

History of past illness

Case 1:The 81-year-old patient’s medical history included hepatitis B virus-associated well-compensated (i.e.,Child-Pugh classification stage A5) liver cirrhosis with portal hypertension and F1 oesophageal varices.

Case 2:Patient 2 had a previous history of dysmotility-like dyspepsia,for which the routine abdominal ultrasonography had been requested.

Case 3:Patient 3 was recovering from sepsis caused by infection of an aortal prosthesis and had no history of past illnesses relevant to the subsequent PVA finding.

Physical examination

Physical examination did not reveal any relevant signs in any of the patients.

Laboratory examinations

Blood testing of Case 2 affected by liver cirrhosis showed leucopenia,thrombocytopenia,and increased level of gamma globulins (2.3 g/dL; normal range:0.7-1.6 g/dL) while blood testing of the other two patients yielded no abnormal findings.

Imaging examinations

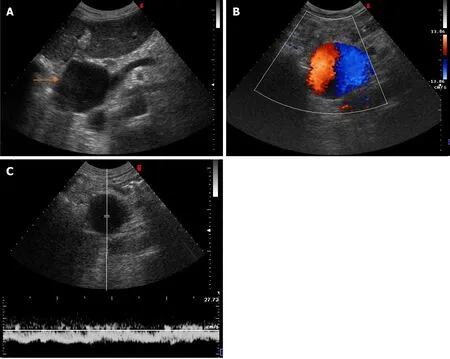

Case 1:Ultrasound examination of patient 1 showed an extrahepatic aneurysmal dilatation of the portal vein (Figure 1A),with a maximal diameter of 48 mm. Colour Doppler examination showed the lesion to have the typical “Korean flag” appearance(Figure 1B),and a Doppler recording revealed flat venous flow (Figure 1C).

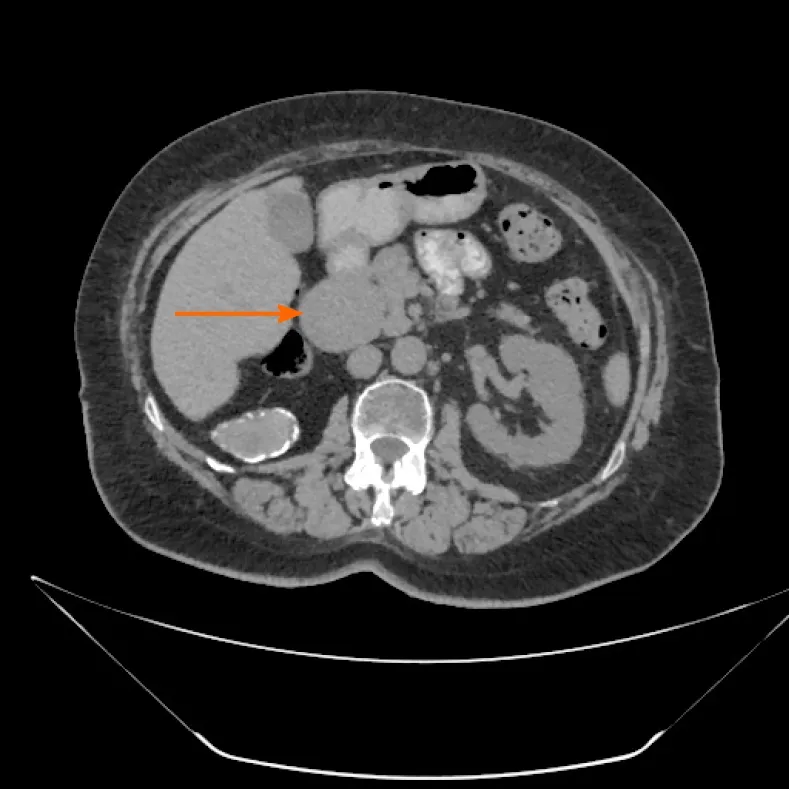

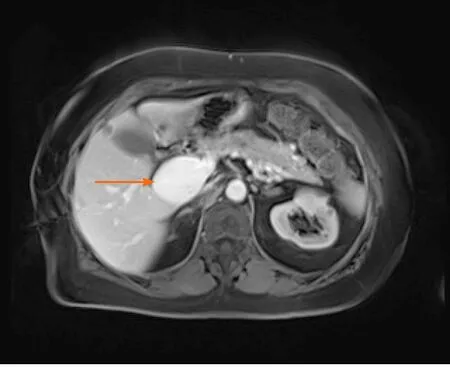

Case 2:Ultrasonographic examination of patient 2 detected extrahepatic aneurysmal dilatation of the portal vein (Figure 2A),with a maximal diameter of 42.3 mm(Figure 2B). Colour Doppler control examination showed a hepatopetal venous flow(Figure 2C) and a pulsating flow of venous type (Figure 2D). Considering the young age of the patient,second-level imaging techniques were performed. Abdominal CT(Figure 3) as well as contrast-enhanced MRI (Figure 4) confirmed the diagnosis of extrahepatic aneurysmal dilatation of portal vein.

Case 3:Abdominal ultrasonography of patient 3 showed an aneurysmal dilatation of the right branch of the portal vein (Figure 5A),with a maximal diameter of 27 mm(Figure 5B) and a typical “Korean flag” appearance (Figure 5C). No further diagnostic procedures were considered necessary.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Cases 1 and 2 were diagnosed with an acquired asymptomatic extrahepatic PVA while Case 3 was diagnosed with an acquired asymptomatic intrahepatic PVA.

TREATMENT

Due to lack of symptoms,ultrasonography surveillance every 6 mo was recommended. No specific treatment was prescribed.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

For the 3-,5- and 1-year of follow-up respectively,all the patients remained asymptomatic and no changes had been detected in the aneurysm measures.

DISCUSSION

PVA is a saccular or fusiform portal vein dilatation that was first described in 1956[5].The commonest classifications divide PVAs into congenital or acquired,symptomatic or asymptomatic,and complicated or uncomplicated[2,6]. To date,the PVA reports in the literature are relatively scarce. A systematic review of 96 reports by Laurenziet al[1]showed that the median age at diagnosis among 190 subjects was 52-year-old (0-89)with portal hypertension and liver cirrhosis discovered in 62 (32%) and 50 (26%)patients respectively with males and females being equally affected. Interestingly,the more recent studies describing PVA cases have shown weaker associations of the condition with chronic liver diseases or portal hypertension[7,8]. This is probably due to implementation and advancement of imaging techniques and of specific knowledge of specialists in the field. While chronic liver diseases remain the commonest acquired causal factors of PVA,other acquired cases are considered to originate from malignant invasion of the vein,inflammatory process due to pancreatitis,or trauma[6]. Most commonly,symptoms occur in patients with large extrahepatic aneurysmal dilatations while small aneurysms often remain asymptomatic[8,9]. Once thrombosed,PVA causes symptoms such as abdominal pain in 91%,fever in 53% and ascites in 38% of patients[10]. Authors noted that in symptomatic patients with or without portal hypertension,symptoms do not differ,except for gastrointestinal bleeding in patients suffering from elevated pressure in portal vein[1]. Unfortunately,no clear evidence exists helping to prospectively distinguish between aneurysms which will have a stable coursevsthose that are potentially complicated but it seems that unfavourable precursors of symptomatic and/or complicated disease are large size (> 3 cm),liver and/or pancreatic diseases and thrombophilic risks. Kocet al[11]reported an incidence of thrombophilia in 4 out of 7 patients with thrombosed PVA,hence,pointing on an importance of thrombophilic screening in all the subjects with diagnosed PVA,even if asymptomatic at the beginning. Even though 18 cases of non-thrombosed PVAs exceeding 5 cm in their largest diameter were reported in the literature,with no anticoagulation taken before their diagnosis,many authors support a thrombophilic risk assessment[12]. While all of our patients were asymptomatic,only one (i.e.,the 81-year-old male) had predisposing factors to the formation of the portal aneurysm,namely hepatitis B virus-associated liver cirrhosis complicated with portal hypertension and oesophageal varices. A thorough examination of the other two patients did not reveal any predisposing risk factors. None of our patients had complications at the time of the first visit nor during the follow-up period. This is at odds with previous reports showing that abdominal pain occurs in approximately 50%of patients and upper gastrointestinal bleeding in less than 10%[2].

Figure 1 Abdominal ultrasonographic imaging of Case 1. A:Anechoic lesion corresponding to a notably dilated extrahepatic portal vein (arrow); B:Colour Doppler showed the “Korean flag” pathological sign in the dilated portal vein; C:Doppler recording showed flat venous flow.

In general,complications of PVA vary depending on the location of the aneurysm and predisposing factors and include aneurysm thrombosis,rupture of the aneurysm,and compression of adjacent anatomical structures,such as the common bile duct,duodenum,or inferior vena cava[1,2]. Hence,complication risk assessment is a crucial management step that could help to avoid life-threatening outcomes of this condition.For patients with no risk factors for complications,a conservative strategy and followup surveillance using abdominal ultrasonography can be recommended,for up to 6 years or until resolution of the aneurysm[1,2,13]. While,in some studies,CT scan every 12 mo was the preferred surveillance strategy[14],the majority of published studies agree with ultrasonography being the preferred imaging technique for surveillance and monitoring of PVA growth,as it is relatively inexpensive and does not involve radiation exposure[15,16]. Maet al[17]suggested a surveillance colour Doppler scanning as the method of choice for diagnosis and surveillance of aneurysms that are asymptomatic and do not increase in size over time while CT scan to be reserved for symptomatic lesions or indeterminate abdominal ultrasound scanning results.Moreover,ultrasonography is capable of differentiating a PVA from a hypervascular pancreatic mass[16],while contrast-enhanced CT and MRI are helpful in cases of diagnostic uncertainty between thrombosis and slow venous flow[18]. Second-level imaging techniques might also be helpful in differentiating compression of the surrounding viscera or rupture[15,18]. CT or MRI are,however,essential when planning surgical intervention[15,17].

Figure 2 Abdominal ultrasonographic imaging of Case 2. A:Extrahepatic anechoic saccular lesion,indicating an aneurysmal dilation of the extrahepatic portal vein (arrow); B:The anechoic lesion was 42.3 mm at its maximal diameter; C:Colour Doppler showed hepatopetal venous flow in the extrahepatic aneurysmal dilated vessel; D:Doppler recording showed pulsating flow of venous type.

Figure 3 Abdominal computed tomographic scanning of Case 2. The axial image showed saccular extrahepatic aneurysmal dilatation of the portal vein(arrow).

After evaluation of our patients’ health status,the conservative management strategy was chosen for each. In the long-term follow-up,none presented any change in aneurysmal dimension. Thus,it was decided to continue regular ultrasonographic examination. This decision was also supposed by studies that have shown partial or total regression of large PVAs over longer periods[13,14].

While the management strategy of large asymptomatic PVAs is still under debate,indications for active management are abdominal pain and occurrence of complications[1,2]. Surgical management depends on the aneurysm location and the presence of thrombi and portal hypertension. Aneurysmorrhaphy and aneurysmectomy are recommended in the absence of portal hypertension,while shunt procedures or liver transplantation are performed in case of portal hypertension[1,4,16].Thrombolysis or thrombectomy are indicated in case of PVA thrombotic obstruction[2],even though a case of conservative treatment was reported for a patient with PVA measuring 88 mm × 65 mm and complete thrombosis extending to the superior mesenteric and splenic veins[19].

Figure 4 Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen of Case 2. The axial image showed saccular extrahepatic aneurysmal dilatation of the portal vein (arrow).

Figure 5 Abdominal ultrasonographic imaging of Case 3. A:Anechoic lesion of the right branch of the portal vein (arrow); B:The intrahepatic anechoic lesion was 27 mm at its maximal diameter; C:Colour Doppler showed the “Korean flag” pathological sign.

CONCLUSION

Our cases,together with the review of the literature,support the concept that the management approach to PVA should be individualized,taking into account aneurysm size,complication risks,medical history,and presence of symptoms.Furthermore,our study highlights the need for gastroenterologists and radiologists to be familiar with PVA imaging features and those that facilitate differential diagnosis between PVA and other lesions,such as hypervascular abdominal masses[16].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the Clinical and Experimental Medical Sciences Doctorate Program of Università degli Studi della Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli".

杂志排行

World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Pathologic and molecular features of hepatocellular carcinoma:An update

- Infantile giant cell hepatitis with autoimmune hemolytic anemia

- Long-term albumin infusion in decompensated cirrhosis:A review of current literature

- Bile acid indices as biomarkers for liver diseases I:Diagnostic markers

- Elderly patients (≥80years) with acute calculous cholangitis have similar outcomes as non-elderly patients (<80years):Propensity score-matched analysis

- Retrospective analysis of complications related to endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography in patients with cirrhosis vs patients without cirrhosis