Infantile giant cell hepatitis with autoimmune hemolytic anemia

2021-05-08

Dimitri Poddighe,Aidana Madiyeva,Diana Talipova, Department of Medicine,Nazarbayev University School of Medicine,Nur-Sultan 010000,Kazakhstan

Dimitri Poddighe,Balzhan Umirbekova, Department of Pediatrics,National Research Center for Maternal and Child Health,Nur-Sultan 010000,Kazakhstan

Abstract Giant cell hepatitis (GCH) is characterized by large and multinucleated (syncytial)hepatocytes in the context of liver inflammation. Infantile GCH is typically associated with autoimmune hemolytic anemia in the absence of any other systemic or organ-specific autoimmune comorbidity. The etiology is unknown;concomitant viral infections (as potential trigger factors) have been identified in a few patients. The pathogenesis reportedly relies upon immune-mediated/autoimmune mechanisms. This condition should be considered in any infant developing Coombs-positive anemia; indeed,anemia usually precedes the development of hepatitis. The clinical course is usually aggressive without the appropriate immunosuppressive therapy,which may include steroids,conventional immunosuppressors (e.g.,azathioprine and cyclophosphamide as first-line treatments),intravenous immunoglobulin,and biologics (rituximab).Improvements in medical management (including the availability of rituximab)have significantly reduced the mortality of this condition in the last decade.

Key Words: Giant cell hepatitis; Autoimmune hemolytic anemia; Rituximab; Infantile hepatitis; Jaundice; Hyperbilirubinemia

INTRODUCTION

Giant cell hepatitis (GCH) refers to a histopathological picture of liver inflammation characterized by large and multinucleated (syncytial) hepatocytes; ≥4-5 nuclei can be seen in the affected cells of the liver parenchyma,along with other features of hepatitis such as lobular fibrotic rearrangements,Kupffer cell hypertrophy,and spotty necrosis[1,2].

In adults,GCH is rare; indeed,it is mainly observed and described in children,mostly in the first years of life. The giant cell transformation of hepatocytes is considered as an altered/dysfunctional regenerative response of hepatocytes in the context of different underlying liver diseases,such as chronic autoimmune hepatitis(AIH),and/or exposure to various noxious agents including drugs and viral infections[2-4].

The histopathological finding of partial or diffuse giant cell transformation of hepatocytes is more frequent in infantile,and in particular,neonatal hepatitis. Indeed,GCH is considered in the differential diagnosis of neonatal cholestasis,where biliary atresia and idiopathic/GCH account for 70% to 80% of all cases; the diagnostic workup usually includes liver biopsy to achieve a complete and final diagnosis[1,5,6]. GCH is also associated with congenital atresia,and thus,both conditions may coexist.However,neonatal GCH has been described in patients with pathological nonobstructive neonatal jaundice (e.g.,blood group incompatibility,hereditary spherocytosis),congenital syphilis,perinatal hemochromatosis,viral infections (e.g.,cytomegalovirus,rubella) and metabolic diseases[7,8]. Torbensonet al[1]analyzed the etiology of GCH in 62 newborns:49% of cases were idiopathic,whereas the remaining patients were variably affected with hypopituitarism (15%),biliary atresia (8%),Alagille syndrome (6%),progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis or other bile salts defects (6%),neonatal hemochromatosis (5%),viral infections (4%),and other diseases(8%,i.e.cystic fibrosis,alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency,severe combined immunodeficiency,AIH)[1].

Infantile GCH is rarely described in patients with post-neonatal hepatitis,and interestingly,is typically associated with autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AHA); this condition is mostly diagnosed in children aged 1 mo to 2 years[9]. Such a pathological association is unusual in post-infantile (childhood and adult) GCH. Indeed,Coombspositive anemia is found in < 10%-15% cases[10]. Infantile GCH + AHA,as a specific disease pattern,was first recognized in 1981 by Bernardet al[11],who described 4 children developing chronic AHA combined with liver disease,which was histologically characterized by severe hepatitis with “diffuse giant cell transformation and extensive fibrosis”[11].

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

The etiology of GCH + AHA is unknown and specific and/or clear trigger factors have not been identified. Indeed,no individual etiological clues have been identified in most patients,except for some cases in whom viral infections (e.g.,paramyxoviruses,varicella-zoster virus,cytomegalovirus) have been reported[4,12-14].

The pathogenesis of GCH + AHA reportedly relies on immune mediated/autoimmune mechanisms,even though this was not included in the classification of pediatric autoimmune liver diseases,according to a recent European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition hepatology committee position statement,which considered three liver disorders:AIH,autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis,andde novoAIH after liver transplant[15]. However,several clinical and pathological findings suggest the involvement of immunological mechanisms in infantile GCH,in addition to the AHA comorbidity by itself. Indeed,Nastasioet al[16]summarized these aspects,including the response to immunosuppressive therapies,the evidence of complement-mediated (C3a- and C5a-driven) hepatocyte injury and liver inflammation,and the sporadic association with autoimmune diseases other than AHA[16]. Importantly,the typical histological features of GCH + AHA differ from those described in the aforementioned “classical AIH,” and in fact,autoimmune liver disease-related autoantibodies are absent. However,a “strong immune/autoimmune component” characterizes the pathogenesis of GCH + AHA[17].

Interestingly,Whitingtonet al[18]emphasized that the histopathology of GCH +AHA is similar to that of Gestational Alloimmune Liver Disease (GALD),which accounts for most cases of neonatal hemochromatosis,characterized by a prominent liver giant cell transformation as well[18,19]. The authors showed that,unlike AIH patients,children with GCH + AHA had diffuse and intense C5b-9 complex deposition in the liver,suggesting that the giant cell transformation in these patients was the result of complement-mediated hepatocyte injury,similar to GALD fetuses and newborns,in whom immunoglobulin G-induced complement-mediated hepatocyte injury has been demonstrated[20,21].

These observations support the fact that GCH + AHA is an autoimmune disease in which giant cell transformation is an “unspecific” reactive response to antibody- and complement-mediated hepatocyte injury. Both hepatitis and Coombs-positive anemia may be consequences of a common systemic B cell immune dysregulation leading to autoantibody production.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND CLINICAL ASPECTS

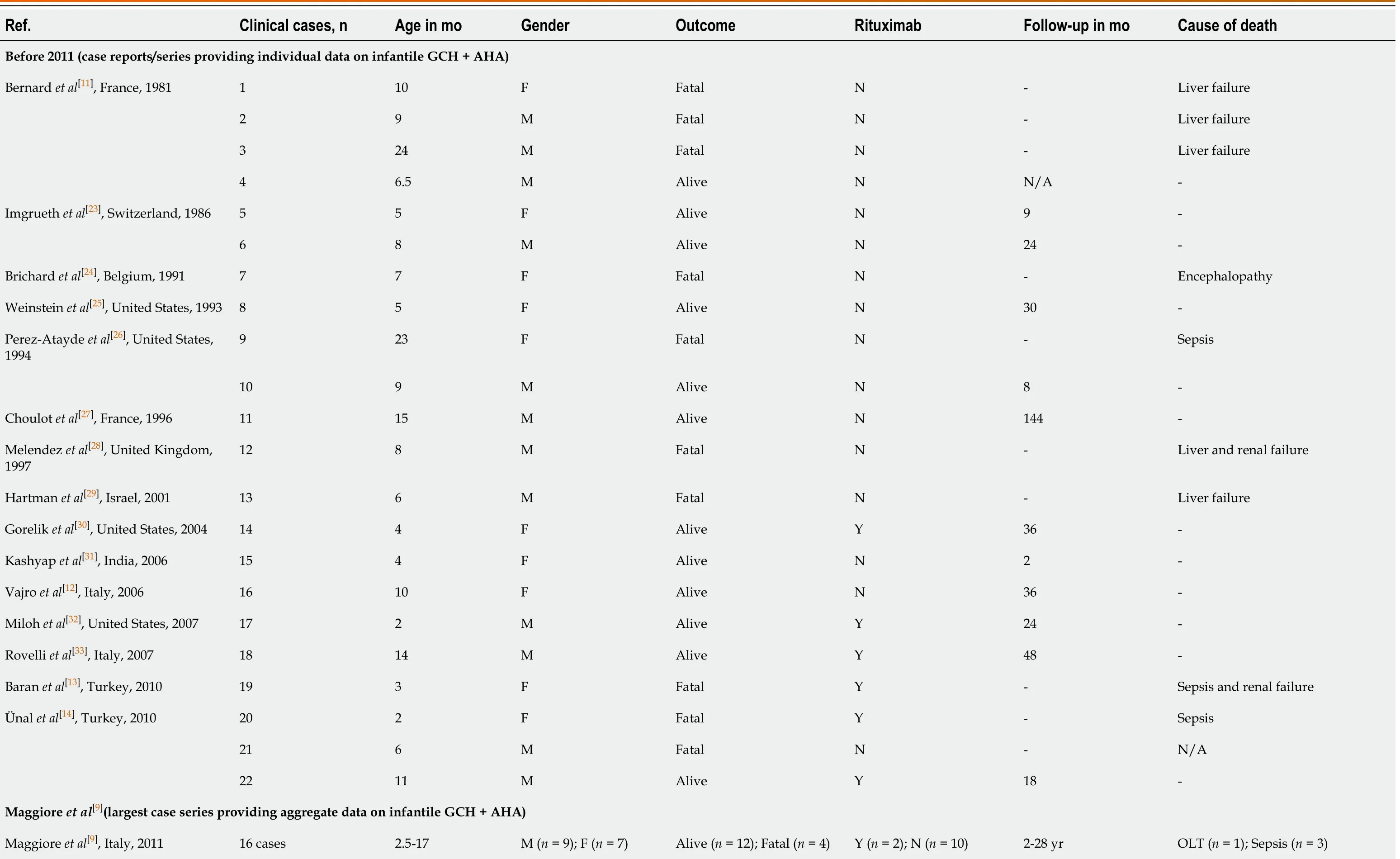

In general,GCH + AHA should be suspected in any child aged 1 mo to 2 years,who presents with severe liver disease and anemia. The median age of the onset is about 8 mo,and thus,most cases manifest before 1 year of age[22]. Both males and females can be affected,without a clear gender preponderance; in the largest cases series published by Maggioreet al[9],there were 9 male and 7 female patients[9]. If all other case reports and small case series are considered (Table 1)[9,11-14,18,22-41],among the 51 reported patients with infantile GCH + AHA,25 were female and 19 were male (no gender specification was available for 7 patients).

In detail,GCH should be considered in any infant developing Coombs-positive AHA,especially if jaundice is direct,namely characterized by a component of conjugated bilirubin > 20% of total bilirubin. Indeed,AHA and,in general,all hemolytic anemia cases usually show jaundice deriving from the accumulation of indirect bilirubin,because its excessive production (due to the increased heme catabolism) cannot be readily cleared from the bloodstream and metabolized by the liver[42]. In summary,whereas isolated AHA (which may also show mild-moderate increase of liver enzymes) is characterized by indirect jaundice,GCH is accompanied by clear signs of cholestasis,and thus direct jaundice,in addition to the fact that the increase in liver enzymes is usually very pronounced.

Indeed,the increase in aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) is usually at least 15-20 times higher than the upper normal limit of the respective age-related reference range[9],but cases with milder liver enzyme elevation (< 5-10 times the upper normal limit) have been described,especially in the initial phases of hemolytic disease[31,37,39]. In this regard,the development of anemia usually precedes the onset of liver disease by a variable period of time,ranging from 1 mo to > 1 year. Therefore,the diagnosis of GCH + AHA often follows a previous diagnosis of isolated AHA[31].

Moreover,the increase in gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) is not usually very pronounced and is often not greater than 2-3 times the age-related upper normal limit[9,38]. Such a GGT increase,especially when associated with mild to moderate AST/ALT abnormalities,could be consistent with several common infectious illnesses(e.g.,cytomegalovirus,Epstein-Barr virus,mycoplasma pneumoniae)[43-45],which may also trigger immune-mediated hemolytic diseases,and thus,should be appropriately excluded through diagnostic work-up[46,47].

Therefore,the measurement of ALT,AST,and GGT is recommended in all young children diagnosed with AHA at the onset and during follow-up of the disease. If liver enzymes are highly and/or persistently elevated without any clear (infectious)explanation,these children should undergo liver biopsy to assess the liver histopathological features,and in detail,whether GCH is present[9]. In addition to a histopathological picture inconsistent with AIH,these patients are serologically negative for significant titers of anti-mitochondrial,anti-smooth muscle,anti-liver kidney microsomal autoantibodies,and anti-nuclear antibodies[31].

Table 1 Overview of the demographic features and outcome in patients with infantile giant cell hepatitis and autoimmune hemolytic anemia

After 2011 (case reports/series providing individual data on infantile GCH + AHA)Raj et al[22],United States,2011 1 6 F Alive N 30-Lega et al[34],Italy,2013 2 8 M Alive N 6-Bouguila et al[35],Tunisia,2013 3 9 N/A Fatal N -Sepsis Whitington et al[18],Canada & United States,2014 4 22 F Alive Y 48-5 14 F Alive Y 48-6 6 F Alive N 48-7 4 F Fatal N -N/A 8 6 M Alive Y 36-Bakula et al[36],Poland,2014 9 7 N/A Alive Y 30-10 8 N/A Alive Y 26-11 2 N/A Alive Y 5-12 12 N/A Alive Y 76-13 7 N/A Fatal N -Hemophagocytosis (after HSCT)Paganelli et al[37],Italy,2014 14 3 F Alive Y N/A1-15 14 F Alive Y N/A1-16 12 F Alive Y N/A1-17 16 M Alive Y N/A1-Marsalli et al[38],Italy,2016 18 5 F Alive N N/A1-19 8 M Alive N N/A1-20 10 F Alive N N/A1-21 10 F Alive N N/A1-22 6 F Alive Y N/A1-23 7 F Alive N N/A1-24 8 M Alive N N/A1-Cho et al[39],South Korea,2016 25 2 N/A Alive N 36-Matarazzo et al[40],Italy,2020 26 5 F Alive Y 141-

1The authors did not provide the follow-up length for individual patients; however,they provided general information on follow-up in their respective case series (Paganelli et al[37]:“At last follow-up visit,all patients were alive with their native liver 2 to 16 year after disease presentation”; Marsalli et al[38]:“Follow-up (median 17.4 mo,range 7-24 mo).” F:Female; HSCT:Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; M:Male; N/A:Not available; N:No; OLT:Orthotopic liver transplantation; Y:Yes.

PROGNOSIS AND THERAPY

The clinical course of GCH + AHA is usually aggressive. According to the analysis of 22 cases reported to 2006,the mortality rate was about 45%. The Italian-French multicentric analysis including 16 pediatric patients (evaluated over a 28-year period and published by Maggiore et al[9]) reported a lower mortality rate (25%),probably due to a better therapeutic (i.e. immunosuppressive) approach over time. Indeed,if the cases reported after 2011 are specifically considered,only 3 of 29 patients died,which corresponds to an overall mortality rate as low as 10% (Table 1)[9,11-14,18,22-41]. The therapeutic regimens described in these case reports and small case series were widely heterogeneous. Such a discussion goes beyond the scope of this review,but it is worth mentioning that the biological therapy with rituximab was part of the treatment of many more patients after 2011 (rituximab used in 16 of 29 cases) compared to the previous period (rituximab used in 8 of 48 cases),which may have contributed to the reduced mortality in the cases described in the last decade. Indeed,despite an initial response to immunosuppressive therapy,relapses occur in many cases,and liver disease/failure is the main pathological component accounting for a negative prognosis. The hematological component is usually better controlled with immunosuppressive therapy. In fact,persistent and clinically relevant hemolysis has been described in a few patients,who required splenectomy and/or plasmapheresis to control a severe and resistant hematological condition[27,29].

In general,liver disease can be controlled in half of patients with initial immunosuppressive therapy,which may be withdrawn in very few patients. The remaining patients develop more severe disease,which is only partially responsive (or not responsive at all) to immunosuppressive therapy; in some of these cases,the clinical course is rapid and fatal,because of the liver failure by itself and/or its complications,such as severe seizures disorder/encephalopathy and/or concomitant infections[12,29]. Indeed,these children may also develop hemophagocytosis leading to a clinical picture of macrophage activation syndrome,as first described by Hartman et al[29].

In those clinical cases with the most severe prognosis,orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) was also considered. However,the prognosis remained poor. In 1997,Melendez et al[28]revised 4 cases undergoing this procedure and 3 of them ultimately died. Importantly,all of these patients showed recurrence of GCH in the transplanted liver within the first few months[28]. A positive transplantation outcome without relapse was described by Kerkaret al[48]in a patient developing progressive hepatic encephalopathy. However,despite the association with Coombs-positive anemia,this patient may have not been a case of infantile GCH + AHA,since he had positive antiliver kidney microsome antibodies,and only partial/patchy giant cell transformation was observed in the liver. Moreover,anemia was associated with thrombocytopenia,suggesting the possibility of type 2 AIH or systemic autoimmune dysfunction leading to several organ immune-mediated disorders,as further supported by the appearance of bullous pemphigoid after liver transplant[48]. Due to constant disease relapses after OLT,such a therapeutic approach has been basically abandoned in the clinical setting of GCH + AHA[12].

Without rapid and appropriate immunosuppressive treatment,the liver function rapidly deteriorates in these patients with infantile GCH + AHA,leading to a progressive and fatal course,as already mentioned. The early institution of an aggressive steroids therapy usually has beneficial effects on both liver function and autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Combination therapy with steroids and azathioprine/cyclophosphamide is often the first-line therapy,which is able to significantly reduce mortality in the early phases of disease activity[31]. However,due to the frequent steroid-resistant cases and/or relapses after immunosuppression step-down/withdrawal,several and additional immunosuppressive agents have been variably used (based upon all the available case reports and series),including cyclosporine,tacrolimus,6-mercaptopurine,mycophenolate and vincristine[12].

In addition to these immunosuppressive drugs,some immunomodulatory therapies have also been used[23,26,29]. In this regard,the first experiences included the use of intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIGs),which were administered according to variable therapeutic schemes,as reviewed by Legaet al[34].Actually,these authors used a highdose regimen (2 g/kg) that was repeated on a monthly basis for more than 6 mo,in association with immunosuppressive therapy[34]. Marsalliet al[38]focused their study on IVIG use and concluded that this treatment can help to significantly and rapidly reduce the activity of the liver disease,in combination with prednisone and other immunosuppressive therapies[38]. Some authors also reported the use of plasmapheresis[23,29,30].

However,as mentioned above,the most important advances in infantile GCH +AHA derived from the use of rituximab. In 2004,Goreliket al[30]reported its use to treat the hematological component,but Milohet al[32]first reported a GCH + AHA infant affected with severe liver disease resistant to steroids,azathioprine,sirolimus,and IVIG,who significantly improved after the therapy with rituximab[30,32].Eventually,several authors reported the successful use of rituximab. For instance,Bakulaet al[36]reported 4 GCH + AHA infants,who achieved complete remission with rituximab after the failure of the first-line therapy with steroids and azathioprine.Therefore,these authors and others proposed rituximab as the treatment of choice for the early stages of the disease[36,40]. Indeed,unresponsiveness to rituximab is suggested to be more likely when its use is delayed[13]. Additional experiences confirmed the safety and effectiveness of rituximab,even in association with other immunosuppressive agents (e.g.,cyclosporine). Moreover,the early treatment could reduce the use of steroids and,thus,prevent several side effects[37]. In some patients,rituximab induced a complete and long-lasting remission and allowed the discontinuation of all immunosuppressive drugs[40]. To conclude,Rovelliet al[33]reported a positive result by using alemtuzumab,which is a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against CD52 (cluster of differentiation 52,a glycoprotein expressed on circulating T and B lymphocytes and natural-killer cells). Even though long-term remission of the liver disease was reported in this case of GCH + AHA,to date,this is the only experience with alemtuzumab.

CONCLUSION

Infantile GCH is a clinical condition that should be considered in any infant developing Coombs-positive anemia,in the presence of significant abnormalities of liver function tests and direct hyperbilirubinemia. Indeed,anemia usually precedes the development of hepatitis. This clinical condition requires timely and appropriate immunosuppressive therapy,which may include steroids,conventional immunosuppressors,intravenous immunoglobulin,and biologics (rituximab).Improvements in the medical management (including the availability of rituximab)have significantly reduced the mortality of this condition in the last decade.

杂志排行

World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Pathologic and molecular features of hepatocellular carcinoma:An update

- Long-term albumin infusion in decompensated cirrhosis:A review of current literature

- Bile acid indices as biomarkers for liver diseases I:Diagnostic markers

- Elderly patients (≥80years) with acute calculous cholangitis have similar outcomes as non-elderly patients (<80years):Propensity score-matched analysis

- Retrospective analysis of complications related to endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography in patients with cirrhosis vs patients without cirrhosis

- Fatal arterial hemorrhage after pancreaticoduodenectomy:How do we simultaneously accomplish complete hemostasis and hepatic arterial flow?