环境和人体中氯代/溴代多环芳烃的研究进展——污染来源、分析方法和污染特征

2021-04-30刘明洋李会茹宋爱民胡建芳盛国英彭平安

刘明洋,李会茹,宋爱民,胡建芳,盛国英,彭平安*

环境和人体中氯代/溴代多环芳烃的研究进展——污染来源、分析方法和污染特征

刘明洋1,4,李会茹2,3,宋爱民1,4,胡建芳1,盛国英1,彭平安1,4*

(1.中国科学院广州地球化学研究所,有机地球化学国家重点实验室和广东省环境资源利用与保护重点实验室,广东 广州 510640;2.华南师范大学环境研究院,广东省化学品污染与环境安全重点实验室&环境理论化学教育部重点实验室,广东 广州 510006;3.华南师范大学环境学院,广东 广州 510006;4.中国科学院大学,北京 100049)

氯代/溴代多环芳烃(Cl/Br-PAHs)是一类具有与二噁英和多环芳烃(PAHs)相似结构和致癌效应的新兴持久性毒害污染物,其环境行为归趋和潜在风险受到了高度重视.本研究以"Cl-PAH*" OR "Br-PAH*" OR "H-PAH*" OR "chlorinated PAH*" OR "brominated PAH*" OR "halogenated PAHs" OR "chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon*" OR "brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon*" OR "halogenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon*"为主题对Web of Science核心合集数据库进行了检索,并着重对环境/人体中Cl/Br-PAHs污染来源、污染特征和分析方法的研究进展进行了综述.结果表明:截止2021年1月,环境/人体中Cl/Br-PAHs的相关文献共计225篇.这些研究表明:Cl/Br-PAHs主要来源于废弃物焚烧、汽车尾气排放、金属冶炼、电子垃圾拆解等热过程和光化学反应过程;目前已在全球各类环境介质中被检出,并表现出持久存在性、长距离迁移性和生物可利用性;Cl/Br-PAHs被证实具有与其母体PAHs相似甚至更强的毒性,但目前对其形成机理和环境行为尚不明确,也尚未有统一有效且精准的分析方法,已报道的化合物种类十分有限,总体研究处于起步阶段.结合目前Cl/Br-PAHs的研究现状和存在的问题,今后应在其高通量精准筛查分析、源排放指纹识别追溯、环境迁移转化行为及潜在风险上开展研究.

氯代/溴代多环芳烃;芳香受体效应;气相色谱-质谱联用

氯代/溴代多环芳烃(Cl/Br-PAHs)是多环芳烃(PAHs)芳环结构上的一个或多个氢原子被氯/溴原子取代而形成的衍生物[1],结构上类似于氯/溴代二噁英和PAHs的杂交体,其形成过程也与二噁英和PAHs类似[2].但不同的是,虽然Cl/Br-PAHs的环境污染问题在20世纪70年代已引起注意,但整体研究起步较晚[3],直到21世纪初相关研究才得以进一步展开[4].研究表明,Cl/Br-PAHs和二噁英、PAHs一样能在环境中稳定持久存在,可被鱼类和哺乳动物等吸收并在脂肪组织中累积[5],表现出与其母体PAHs相当甚至更高的致癌、致畸、致突变毒性,是一类新兴高风险毒害有机污染物,对生态环境和人类健康存在潜在危害[6].

据文献报道,目前对于Cl/Br-PAHs的研究主要集中在与多氯联苯(PCBs)结构类似的多氯萘(PCNs)上[4,7-10],但对3环及以上的Cl/Br-PAHs研究却十分有限,主要原因是该类污染物种类繁多,在环境中多为超痕量浓度水平,净化分离难度大,且缺乏标准品,目前尚未有统一的分析方法.本文通过对Web of Science 核心合集数据库中相关文献的检索,综述了近年来环境/人体中Cl/Br-PAHs的污染来源、分析方法和污染特征的研究进展,对目前的研究现状、存在的问题及研究数据缺口进行了梳理分析,并由此提出其今后的研究方向.

1 Cl/Br-PAHs的污染来源

1.1 汽车尾气排放

汽车尾气是城市环境中Cl/Br-PAHs的主要释放源之一.据报道2016年日本城市空气中有23%的Cl/Br-PAHs来源于道路交通排放,汽油中的二溴乙烷和二氯乙烯等是Cl/Br-PAHs形成的主要卤源[11]. Ishaq等[12]发现含氯汽油使用的减少使得1996年斯德哥尔摩市公路隧道大气Cl-PAHs浓度比1991年降低了10倍,由此认为含氯汽油会影响汽车尾气中Cl-PAHs的形成.Wang等[13]在交通要道土样中检测出的Cl-PAHs浓度是农田表层土壤的40倍.此外,有研究者在高速公路附近的雪样中也检出了一定浓度的Cl/Br-PAHs[14].

1.2 有机物焚烧

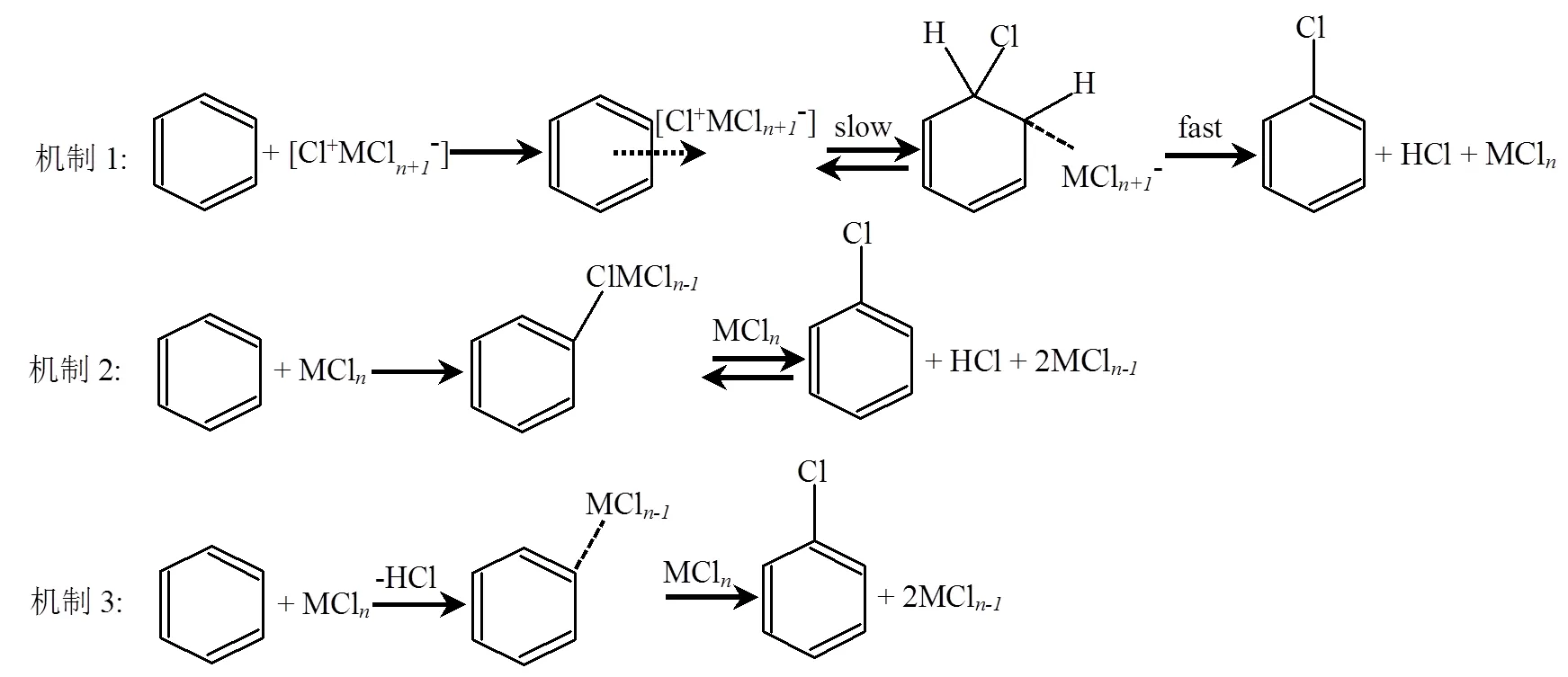

固体废弃物(如城市生活垃圾、电子垃圾等)以及化石燃料(如煤炭)的高温处理或燃烧均可产生大量Cl/Br-PAHs[15-17].其形成机理包括母体PAHs的直接氯化和Cl-PAHs与其他前驱物的二次反应[18].前者一般有2种途径(图1):一是催化氯化,Cl2通过高温下的亲电氯化与PAHs反应或被充当路易斯酸的过渡金属氯化物(如FeCl3、CuCl2等)催化(机制1);二是直接氯化,金属氯化物作为氯化剂反应,通过构成极化的金属氯化物分子或是构成有机金属中间体来促进芳香族化合物的氯取代[24,28-29](机制2和3).固废中常见的聚氯乙烯(PVC)、金属氯化物、溴代阻燃剂(BFRs)等是Cl/Br-PAHs形成的氯/溴源[23-24].Fernando等[25]在PVC焚烧后的土壤样品中检测到高浓度的Cl-PAHs.PVC是电子产品的常用材料,电子垃圾焚烧区土壤、拆解车间灰尘及周边土壤和植物中均已检出高浓度的Cl- PAHs[17,27].Wang等[26]发现PVC在600~900℃范围内燃烧时,Cl-PAHs的形成随温度升高而升高.固废焚烧产生的Cl/Br-PAHs不仅残留在焚烧残渣内,还可随飞灰和烟气释放到环境中[19].Kitazawa等[16]在城市垃圾焚烧炉烟道气中检测出相当高浓度的Cl-PAHs (<5.80~8780ng/m3),是环境大气浓度的350~60000倍;受燃烧效率和条件的影响,不同类型焚烧炉产生的Cl/Br-PAHs浓度也存在显著差异,其中固定炉(0.460~6990ng/g)远高于炉排炉(<0.060~1.10ng/g)和回转窑(<0.060~105ng/g)[20]. Li等[21]通过实验室模拟研究发现Cl-PAHs在气相中浓度较高,而Br-PAHs大多残留在底灰和飞灰中,这与后者分子量较大较难挥发有关[22].相比于末端控制,焚烧过程中的源头控制能更有效的降低Cl/Br-PAHs的污染排放,Qiao等[15]发现随着清洁能源逐步取代燃煤发电取暖,北京市河流中Cl- PAHs的浓度显著降低.

1.3 工业活动

金属冶炼、氯化学工业等工业生产过程均可产生Cl/Br-PAHs.Xu等[30]发现铁、铝、铅等冶金工业烟道气中的Cl-PAHs和Br-PAHs浓度(68.3~156和2.90~13.5ng/Nm3)远高于其周围大气中的浓度(7.00~554和3.00~126pg/m3),且两者化合物组成相似.Jin等[31]在二次铜冶炼厂车间检出了38种Cl/Br-PAHs,总浓度2.20~605pg/m3,高于周边空气浓度(2.50~92.3pg/m3).冶炼原材料、燃料、还原剂等是影响金属冶炼过程中Cl/Br-PAHs生成释放的重要因素,使用天然气代替煤和重油作为燃料和还原剂可能有助于降低该过程中Cl/Br-PAHs的形成[30-31].

Pinto等[32]模拟了自来水的消毒过程,在含有PAHs和次氯酸钠的超纯水中检测到一定浓度的Cl-PAHs.Koistinen等[33-34]在牛皮纸漂白厂和纸浆厂的污水、纸浆、生物底泥中均检测出Cl-PAHs,以氯代芴(Cl-FLU)和Cl-PHE为主.图2是水氯化消毒过程中苊(ACE)的主要氯化途径[35].

图1 燃烧过程中PAHs的3种氯化机制[24,28-29]

图2 ACE在水的消毒过程中的氯化途径[35]

除上述工业活动外,Ma等[17]发现焦化厂、PVC制造厂和氯碱厂等厂区表层土壤中的Cl-PAHs (88.0ng/g)比周边农田表层土高2~3个数量级(ND~0.760ng/g).

1.4 光化学反应

PAHs的光化学作用也是Cl/Br-PAHs的重要来源.Sankoda等[36]以芘(PYR)模拟了海水中PAHs的紫外光照射过程,检测到PYR的单氯、单溴、二氯和混合卤代产物.Ohura等[37]观察到PYR和苯丙(a)芘(BaP)与Cl2在紫外光或可见光照射下均可生成以1-Cl-PYR和6-Cl-BaP为主的Cl-PAHs,由此提出了PAHs在含Cl-的酸性溶液中的光氯化机制(1~7):

PAH → PAH*(光照)(1)

PAH* + O2→ PAH+·+ O2-(2)

O2-·+ O2-·+ 2H2O → H2O2+ 2OH-+ O2(3)

O2-·+ H2O2→ OH·+ OH-+ O2(4)

OH·+ Cl-→ HOCl-(5)

HOCl-·+ H+⇆ Cl·+ H2O(6)

PAH + Cl·→ ClPAH(7)

pH值是水环境中Cl的光化学反应的重要影响因素,Cl-PAHs的光化学生成随pH值降低而增加[37].此外,金属氧化物的种类和形态、氯源、光照时间等也会影响光化学反应中Cl-PAHs的形成[38],例如二氧化钛和二氧化硅能促进Cl-PYR的生成,而氧化钙却不能;在二氧化硅的硅酸酐形态中能检测出2-Cl-PYR,而在石英和硅胶等形态中却未检测出[38].氯源、光照时间等也会影响光化学反应过程中Cl-PAHs的形成.二氧化钛中Cl-PYR的生成量在0.5~1h达到峰值,此后随辐射时间增加生成量逐渐降低[38].

2 Cl/Br-PAHs的污染特征

目前研究者已在大气、水体、土壤以及各种生物体中检出了Cl/Br-PAHs(表1),并对其环境行为和污染特征进行了初步研究.

2.1 大气

Kamiya等[11]发现日本名古屋大气悬浮颗粒物中24种Cl-PAHs浓度的空间分布规律为工业地区(20.7pg/m3)>居民区(14.1pg/m3),且Cl-PAHs主要源于受季节影响的本地源,而PAHs主要源于工业和石油燃料燃烧,二者的产生机制差异较大.Ohura等[39]报道日本12个地区大气中的Cl-PAHs呈现出夏季气相浓度较高,而冬季颗粒相浓度较高的季节变化规律,由此推测不同季节Cl-PAHs的来源可能存在差异,其夏季来源可能是废弃物焚烧,而冬季来源可能是车辆尾气排放和燃煤.Jin等[40]发现煤燃烧的增加使得供暖期间北京大气中Cl/Br-PAHs的平均浓度比非供暖期间高3~9倍,这与Kakimoto等[41]的研究一致.此外,Kakimoto等[41]认为不同季节的光化学降解差异也会导致Cl/Br-PAHs浓度的季节性.以上研究中报道的Cl/Br-PAHs以BaP和PYR的单氯化衍生物为主,对高取代或混合取代的Cl/Br-PAHs报道很少.

大气中的Cl/Br-PAHs主要存在于大气颗粒物中并能保持相对稳定.Helm等[42]在北极地区大气中检测出一定含量的PCNs,证实了Cl/Br-PAHs具有较强的大气远距离迁移传输能力.

2.2 水体

大多数Cl/Br-PAHs水溶性很低,在水环境中主要赋存在悬浮颗粒物和沉积物上.Sun等[43]在深圳茂州河的表层沉积物中检出了3种Cl-PAHs和6种Br-PAHs,分别以9-Cl-PHE(平均浓度16.5ng/g)和2-Br-FLU(平均浓度35.3ng/g)为主,且Br-PAHs总浓度是现有研究报道中最高值(平均浓度53.0ng/g),城市化和工业化进程是其主要来源. Ohura等[44]在亚洲3个受工业化影响区域的水体(中国黄海,斯里兰卡的康提湖和尼甘布泻湖)沉积物中检测出Cl/Br-PAHs,以6-Cl-BaP、1-Cl- PYR、3-Cl-FLT等为主,在表层沉积物浓度较高,而PAHs则在底层沉积物浓度较高.作者认为影响两者分布的主要因素是各自污染来源及迁移转化过程(如光降解、生物降解等),某些Cl-PAHs同系物如6-Cl-BaP和1-Cl-PYR可作为其人为活动源的指示物[43].

Shiraishi等[2]在筑波地区自来水样本中检测出萘(NAP)、菲(PHE)、芴(FLU)和荧蒽(FLT)的一氯/二氯衍生物但在地表水中未检测出,推测自来水中的Cl-PAHs主要来源于氯化消毒及管道传输过程.而Wang等[45]在河南洛阳某区的研究发现水样中Cl-PAHs浓度表现为地表水(6.90~25.7ng/L)>自来水(0.900~25.7ng/L).这可能是由于城市化进程产生了Cl-PAHs的潜在排放源,如电子废物回收、氯化学工业、汽车尾气等,通过污水排放、地表径流、地下水渗透等途径向水体中释放Cl-PAHs.海水中也存在着相当高浓度的Cl/Br-PAHs,这可能源于沿海地表水中PAHs暴露于太阳光发生卤化作用[36].

表1 环境中Cl/Br-PAHs的污染特征比较

注:①1,2-Br2-ACY指1,2-二溴苊烯;②2-Br-TRIPH指2-溴三亚苯.

2.3 土壤

Ni等[46]发现土地利用方式可影响土壤中Cl/Br-PAHs的同系物组成和浓度水平,深圳地区8种不同土地利用方式土壤中3种Cl-PAHs的平均浓度依次为:交通区(2.16ng/g)>商业区(1.04ng/g)>农业区(0.330ng/g)>工业区(0.220ng/g)>居民区(0.080ng/g)>果园(0.070ng/g)>森林(0.060ng/g)>绿化区(0.020ng/g),表明汽车尾气排放会影响土壤中的Cl-PAHs含量;而6种Br-PAHs的平均浓度在各土样中均高于Cl-PAHs,且在农业区土壤中的浓度最高(18.1ng/g),说明其主要来源与Cl-PAHs不同.Ni等[46]在土壤样品中检出的9种Cl/Br-PAHs中以2-Br-FLU为主(平均浓度为7.18ng/g),却在飞灰中检出了除2-Br-FLU以外的8种Cl/Br-PAHs,表明飞灰与土壤中Cl/Br-PAHs的来源存在差异.Nguyen等[47]发现电子废物露天焚烧可造成土壤Cl/Br- PAHs污染,且Cl-PAHs浓度比相应Br-PAHs高2.4~64倍,以三环单氯代物为主,其中1-Cl-PYR浓度最高;而Br-PAHs的组成和浓度水平随燃烧材料类型和条件而变化.

2.4 生物体

尽管数据有限,Cl/Br-PAHs已在鱼类、蔬菜等动植物样品中被检出,表现出生物可利用性和生物富集性.Tan等[48]在辽宁省的22个淡水鱼样品中检测出3种低分子量的Cl-PAHs(9- Cl-PHE、1-Cl-PYR和5-Cl-ACE),但并未观察到Cl-PAHs与母体PAHs的相关性,其中工业活动较强地区(如城市垃圾填埋、造纸厂)的鱼样中的Cl-PAHs浓度较高,而生产活动和燃烧源污染严重地区鱼样中PAHs浓度较高;所有鱼样中的Cl-PAHs以低分子量化合物为主,这可能与其生物可利用性较强有关[49]. Wang等[50]发现北京市场上的叶类和根类蔬菜中均可检出11种Cl/Br-PAHs,但叶类蔬菜的总Cl/Br-PAHs浓度高于根类蔬菜,且随着与焚烧厂距离的增加而显著降低,说明其污染主要来自于焚烧污染排放的大气沉降.

2.5 人体

目前对于人体样品中Cl/Br-PAHs的污染特征研究极为有限,现有研究主要集中在Cl/Br-PAHs的人体暴露评价和致癌风险评估方面(表2).有限的研究表明:不考虑体重影响下,男性及成年人的暴露剂量更高,而如果考虑体重的影响,女性和儿童则处于更高的暴露风险中;食物性摄入是人体Cl/Br-PAHs的主要暴露途径[46,51-52].

有研究者[53]认为,Cl/Br-PAHs倾向于在水生生态系统的食物链中被生物利用和放大,污染水产品(如海鲜等)的摄入是其人体暴露的主要途径.除此之外,其它受污染食物(如肉类、大米、蔬菜等)的摄入也会增加其人体暴露风险[51].Ding等[51]通过计算不同年龄段人群每日通过不同食物对9种Cl/Br-PAHs的绝对摄入量(ADI,ng/d)发现,虽然Cl/Br-PAHs总浓度变化顺序为猪肉(4.97ng/g)>大米(2.75ng/g)>蔬菜(0.560ng/g),但各食物对其ADI的贡献则是大米(41.3%~58.7%)>猪肉(27.4%~43%)>蔬菜(6.5%~ 19.6%);成年和老年人的ADI值(男:1129~1253ng/d;女:998.1~1034ng/d)高于儿童(男:581.7ng/d;女: 577.4ng/d);但考虑到体重影响,儿童仍是最敏感暴露人群.

大气颗粒物和土壤灰尘等非食物性摄入也会增加人体的Cl/Br-PAHs暴露风险,但暴露量远低于食物性摄入[40,46,52].Ni等[46]发现同一年龄段女性通过土壤接触对Cl/Br-PAHs的相对每日摄入量(RDI,pg/(kg·d))高于男性,且随年龄增加而降低.Sun等[52]通过计算也发现除成年人外,其余所有年龄段女性通过大气颗粒物PM10和PM2.5摄入Cl/Br-PAHs的RDI值均略高于男性.Jin等[40]比较了不同人群在供暖期和非供暖期通过呼吸和皮肤暴露摄入PAHs和Cl/Br-PAHs的ADI值,发现颗粒相呼吸摄入(33%~98.8%)>气相呼吸摄入(0.5%~39.2%)>气相皮肤暴露(0.2%~40.8%)>颗粒相皮肤暴露(0.004%~0.8%),其中供暖期间的呼吸摄入ADI值比非供暖期间高10倍以上,且ADI值整体表现为成年人>青少年>儿童,颗粒相呼吸摄入被认为是PAHs及Cl/Br-PAHs在雾霾天的主要暴露途径.

对于致癌物质,美国环保局将10-6几率致癌风险值设为可接受致癌风险水平下限,而10-4几率设为可接受致癌风险水平上限[54].Wang等[50]发现所有年龄段人群经蔬菜摄入Cl/Br-PAHs所引发的终生致癌风险(ILCR)值均<10-6,即其癌症风险很小.Ding等[51]报道了深圳地区男性和女性通过饮食摄入(猪肉、大米、蔬菜)8种Cl/Br-PAHs的ILCR值分别为1.20×10-5和1.10×10-5,处于10-6和10-4之间.这一差异可能与各自研究区域、检测Cl/Br-PAHs种类及浓度不同有关.Sun等[52]的研究则表明,虽然不同年龄段人群经PM10和PM2.5呼吸摄入9种Cl/Br-PAHs所引发的ILCR值有所不同,但所有ILCR值都比10-6低2~3个数量级.总的来说,食物性和非食物性摄入Cl/Br-PAHs均存在一定的致癌风险,但目前已有的数据大多低于可接受致癌风险水平上限(10-4).需要注意的是,因为上述评价涵盖的目标物种类均十分有限,Cl/Br-PAHs的实际癌症风险可能要高于上述评估值.

表2 人体Cl/Br-PAHs暴露量及致癌风险评估

3 Cl/Br-PAHs的分析方法

3.1 样品提取

样品提取是准确分析环境样品中Cl/Br-PAHs的关键步骤,最传统的方法是液液萃取(LLE)和索氏抽提(SE),广泛应用于水体、大气、土壤等样品中Cl/Br-PAHs的提取[2,55-57].近年来,随着样品前处理技术的飞速发展,一些新型仪器辅助提取方法被不断推出并应用于环境样品中Cl/Br-PAHs的提取和分析,例如:利用固体吸附及选择性吸附液态样品中目标物的固相萃取法(SPE)[45,58-59];采用涂有固定相的熔融石英纤维来吸附、富集样品中的待测物质的固相微萃取法(SPME)[60];利用超声波辐射加速提取目标物的超声波萃取法(UE)[41,61-62];利用加温加压加速提取目标物的加速溶剂萃取法(ASE)[25,30,48];利用微波加热加速溶剂提取的微波辅助萃取法(MAE)[63-65]等.上述提取方法的优缺点见表3.总的来说,SPE、ASE、UE等新型样品提取技术有机溶剂消耗量低,提取时间短,效率高,容易实现自动化操作,或与分析检测仪器在线联用,大大节省人力物力,未来会在Cl/Br-PAHs的环境/人体样品分析中发挥重要作用.

除上述常见提取方法外还有超临界流体萃取法(SFE),该方法利用超临界流体(如CO2)良好的溶解能力和高扩散性达到萃取分离目的,目前已应用于土壤[66-67]、沉积物[68]、大气[69]等基质中PAHs及其衍生物的提取分析,为Cl/Br-PAHs的提取技术提供新方向.

3.2 样品净化

柱层析法是有机污染物分析最常用的样品净化分离手段.目前Cl/Br-PAHs样品净化常用的柱填料有硅胶、活性炭、氧化铝、弗罗里硅土、凝胶渗透色谱柱填料(GPC)、铜粉/粒(除硫)等[70].这些填料既可单独使用,也可组合以更好的去除样品的基质干扰;既可自行组装,也有不同容量的商品化小柱可以选用.

表3 Cl/Br-PAHs的主要提取方法的比较

3.2.1 单填料固相净化柱 硅胶通过表面硅醇基产生吸附作用,适于分离极性相差较大的物质,还可与酸碱混合配置成酸性或碱性硅胶,用于不同酸碱性干扰物质的去除,是有机物分析中最常用的净化柱填料[71-72].但Jin等[73]考察了不同质量负载(11%、22%、44%,:)下酸性硅胶对Cl/Br- PAHs样品的净化效果,发现即使是最低负载(11%)的酸性硅胶也会完全破坏Cl/Br-PAHs的结构,该研究最终采用中性硅胶对样品进行净化,并用60mL正己烷:二氯甲烷=4:1(:)洗脱,得到了很好的净化效果(加标回收率为77%~106%).碱性硅胶也常用于卤代二噁英样品的净化过程[74]. Masuda等[75]采用12g 2% KOH碱性硅胶柱并结合活性炭小柱,成功将鱼皮样品中的脂质及其碱反应产物与Cl-PAHs分离,净化后目标物回收率为57%~105%.氧化铝对非平面极性分子有较强吸附力,而活性炭可吸附共平面非/弱极性化合物,因此二者适用于分离平面型和非平面型化合物.Fernando等[25]采用活性氧化铝柱净化土壤样品提取液,100mL正己烷淋洗去除样品中的脂肪族化合物,然后以200mL二氯甲烷洗脱其中的Cl/Br- PAHs.莫李桂等[76]采用100mL正己烷:二氯甲烷=7:3 (:)淋洗双层碳可逆管以去除脂肪类碳氢化合物及非共平面PCBs等干扰物,然后用100mL甲苯反冲柱获得Cl/Br-PAHs,加标回收率62%~95%.GPC填料依靠空间排阻效应,将分子体积较大的干扰物质(如脂肪类)从样品中去除.原文婷等[77]以乙酸乙酯:环己烷=1:1(:)做GPC柱洗脱液,6种Cl-PAHs检测限2.60~25.1pg/g.

3.2.2 复合固相净化柱 对于基质复杂的样品,使用单填料净化柱难以达到理想的净化分离效果,通常采用两种及以上的净化填料复合的方式,如硅胶与氧化铝、活性炭或GPC等组合,达到进一步净化样品提取液的目的.Qiao等[78]采用硅胶-氧化铝复合柱净化分析北京某河流水样,不同配比有机溶剂洗脱,目标物回收率在69%~103%之间.多段硅胶柱也是一种常见的复合净化柱,将酸性硅胶、中性硅胶、碱性硅胶等按照不同的质量、排列顺序进行组合, 对基质中极性较高(如脂肪等)和易氧化物质有很好的去除效果[72],被用于沉积物和生物样品中PCNs的净化分析[79].但如前所述[73],酸性硅胶可能会破坏PAHs及其氯代衍生物的结构,导致目标物回收率降低.

3.3 仪器分析

Cl/Br-PAHs的结构和物化性质与PAHs及二噁英等有机物相似,其仪器分析方法的建立主要参考上述有机物,以气相色谱-质谱联用(GC-MS)为主.此外,高分辨气相色谱-高分辨质谱(HRGC- HRMS)、全二维气相色谱-质谱(GC×GC-MS)、气相色谱-串联质谱(GC-MS/MS)等也在Cl/Br-PAHs分析中发挥了很大作用,对Cl/Br-PAHs的检测限可达pg级甚至更低.目前已报道的Cl/Br-PAHs主要仪器分析方法见表4.

3.3.1 GC-MS GC-MS主要采用电子电离源(EI)和四级杆(Q)质量分析器,最早被用于水体样品中的Cl/Br-PAHs分析[10],后来也被用于大气样品分析,定性定量效果良好[39].近年来随着MS技术的飞速发展,轨道离子阱(Orbitrap)、傅里叶变换离子回旋共振分析器(FT-ICR)等高分辨率质量分析器也被用于Cl/Br-PAHs的分析.GC-EI-Orbitrap/MS可检测ppb级的有机污染物,Yang等[80]应用GC-EI-Orbitrap/ MS对不同热处理工业过程中产生的飞灰进行分析,共鉴定出包含Cl/Br-PAHs在内的96种有机化合物.FT-ICR/MS是在回旋共振分析器的基础上发展而来,具有更快的扫描速率和更高的灵敏度. Fernando等[25]借助FT-ICR在火灾过后的土壤样品中鉴定出包含Cl/Br-PAHs在内的约150个化合物分子式.但FT-ICR/MS价格昂贵,体积大,分析速度较慢,成本高,在实际样品分析中应用较少.

3.3.2 HRGC-HRMS HRGC-HRMS在准确分析环境基质中具有复杂同类异构体且超痕量的有机物方面具有压倒性优势.Jin等[31,73]在高分辨率(>10000)和选择离子监测(SIM)模式下,采用HRGC-HRMS分析了二次铜冶炼厂烟道气及周边空气样品中的Cl/Br-PAHs.Fan等[81]采用HRGC- HRMS法分析不同工业热处理飞灰中的Cl/Br- PAHs,均取得了良好效果,其中低氯代PAHs的检测限为3.50~9.50pg/g.

3.3.3 GC×GC-MS 全二维GC(GC×GC)将2个涂层存在差异、分离机理不同且相互独立的色谱柱以串联方式结合,极大提高了分离度和峰容量.Xu等[35]借助GC×GC-Q/MS对Cl/Br-PAHs的定性分析发现ACE和PYR是 Cl-PAHs的主要前体,ACY和ANT则主要产生毒性较小的氧化PAHs.GC×GC若与高分辨率的飞行时间质谱(TOF)联用则同时具有高通量、高灵敏度、高分析速率等优势,适于复杂样品的分离鉴定和全谱分析.Manzano等[82]采用GC×GC- TOF/MS分析大气颗粒物、土壤和沉积物等样品中的PAHs和Cl-PAHs,显著降低了分析时间.Ieda等[83]首次通过GC×GC-TOF/MS分析法,在土壤提取物中检测出了高氯(³7)Cl-PAHs和混合卤素取代的PAHs.尽管GC×GC-TOF/MS对高氯/溴取代PAHs具有明显的分析优势,但其高昂的成本和分析费用使其应用受到限制.

3.3.4 GC-MS/MS 多级MS串联所具有的多反应监测模式(MRM)可对一维MS无法区分的干扰离子进一步确认,有效排除杂质干扰.莫李桂等[76]借助GC-QQQ-MS/MS 对土壤样品中的19种Cl-PAHs和8种Br-PAHs进行分析,目标物的仪器检测限分别为0.400~5.00pg和0.600~3.60pg.GC-QQQ-MS/ MS的检测限和灵敏度与高分辨质谱相当,但硬件相对便宜,分析成本低,具有较好的应用前景.

3.3.5 其他仪器分析方法 Wang等[84]首次尝试采用高效液相色谱 (HPLC)和荧光检测器分析自来水中的6种Cl-PAHs和15种PAHs,目标物检测限0.30~5.00ng/L.也有研究人员将LC-MS应用于水体[85]、土壤[86]、人体组织[87]中PCNs的检测,回收率和检测限均能满足检测要求.但LC-MS常用的离子源如电喷雾电离源(ESI)、大气压化学电离源(APCI)等对Cl/Br-PAHs的电离效率低,基质效应高,因而在Cl/Br-PAHs的分析中应用较少.Gao等[88]借助LC- MS设计了一种鉴定未知PAHs的方法,利用Cl- PAHs在质谱中的同位素分布识别未知PAHs的分子组成和碳骨架,很好的表征了NAP、ANT、PHE、PYR和FLT等PAHs类污染物,灵敏度达1.00ng/mL.

表4 Cl/Br-PAHs的主要仪器分析方法的比较

4 结语

4.1 总结

Cl/Br-PAHs来源和种类繁多,并在环境中表现出普遍存在性、持久性、长距离迁移性、生物富集性和毒性.目前受分析方法和标准品限制,国内外对其污染特征、环境行为归趋和风险的研究尚未全面展开,整体处于起步阶段,存在以下问题:

4.1.1 缺乏统一完善的分析方法体系和商业可获得标准品;目前的靶向分析方法能够分析的Cl/Br- PAHs极为有限,如何分析/表征复杂样品中的多种Cl/Br-PAHs对于环境分析化学家是极大的挑战.

4.1.2 环境/人体中Cl/Br-PAHs的污染数据十分有限,对其在环境中的迁移转化行为、归趋和风险尚不清楚.

4.1.3 对于Cl/Br-PAHs的生成机理、与母体PAHs的关系、影响因素及不同污染排放源的组成指纹特征研究极为有限.

4.1.4 目前的研究主要集中在1~3个Cl/Br单独或混合取代的PAHs上,对于高卤代PAHs污染特征和环境行为的研究有待展开.

4.2 研究展望

作为一类新兴卤代芳烃类毒害有机污染物,Cl/ Br-PAHs的污染和风险已引起国内外研究学者的广泛关注,可以预见,随着研究方法和技术手段的不断发展进步,关于Cl/Br-PAHs的污染及其生态和健康风险研究将会全面展开.结合Cl/Br-PAHs目前的研究现状和存在的问题,今后应在以下方面开展相关研究:

4.2.1 复杂样品中多种Cl/Br-PAHs的分析/表征方法,如高分辨质谱非靶向筛查分析法、生物毒性表征法等.

4.2.2 不同污染来源Cl/Br-PAHs的生成机理、关键控制因素、污染物组成特征指纹谱,不同环境介质中的Cl/Br-PAHs污染来源的判识和追溯,同时提出其污染的源头控制建议.

4.2.3 深入探讨Cl/Br-PAHs在各类环境介质及生物体/人体间的迁移转化规律和潜在生态健康风险.

[1] Ohura T, Amagai T, Makino M. Behavior and prediction of photochemical degradation of chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in cyclohexane [J]. Chemosphere, 2008,70(11):2110- 2117.

[2] Shiraishi H, Pilknington N H, Otsuki A, et al. Occurrence of chlorinated polynuclear aromatic-hydrocarbons in tap water [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 1985,19(7):585-590.

[3] BrinkmanU A T, ekok A, Reymer H G M, et al. Analysis of polychlorinated naphthalenes by high- performance liquid and thin -layer chromatography [J]. Journal of Chromatography, 1976,129(22): 193-209.

[4] Liu Z, Liu G, Zheng M, et al. Progress in the studies associated with environmental distribution and characterization of polychlorinated naphthalenes [J]. Scientia Sinica Chimica, 2013,43(3):279-290.

[5] Gao Z, Yang X, Peng Y. Analytical methods and pollution status of a new class of organic contaminants-chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2016,35(2):287-296.

[6] Loftroth G, Nilsson L, Agurell E, et al. almonella microsome mutagenicity of monochloro derivatives of some di-tetracyclic, tri-tetracyclic and tetracyclic aromatic-hydrocarbons [J]. Mutation Research, 1985,155(3):91-94.

[7] Mahmood A, Malik R N, Li J, et al. Congener specific analysis, spatial distribution and screening-level risk assessment of polychlorinated naphthalenes in water and sediments from two tributaries of the River Chenab, Pakistan [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2014,485: 693-700.

[8] Falandyse J. Polychlorinated naphthalenes: an environmental update [J]. Environmental Pollution, 1998,101(1):77-90.

[9] Kannan K, Hilscherova K, magawa T, et al. Polychlorinated naphthalenes, -biphenyls, -dibenzo-p-dioxins, and -dibenzofurans in double-crested cormorants and herring gulls from Michigan waters of the Great Lakes [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2001,35(3): 441-447.

[10] Kucklick J R, Helm P A. Advances in the environmental analysis of polychlorinated naphthalenes and toxaphene [J]. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 2006,386(4):819-836.

[11] Kamiya Y, Iijima A, Ikemori F, et al. Source apportionment of chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons associated with ambient particles in a Japanese megacity [J]. Scientific Reports, 2016,6:38358.

[12] Ishaq R, Naf C, Zebuhr Y, et al. PCBs, PCNs, PCDD/Fs, PAHs and Cl-PAHs in air and water particulate samples-patterns and variations [J]. Chemosphere, 2003,50(9):1131-1150.

[13] Wang X L, Wu J F, Liu B. Pressurized liquid extraction of chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from soil samples using aqueous solutions [J]. Rsc Advances, 2016,6(83):80017-80023.

[14] Haglund P, Alsberg T, Bergman A, et al. Analysis of halogenated polycyclic aromatic-hydrocarbons in urban air, snow and automobile exhaust [J]. Chemosphere, 1987,16(10-12):2441-2450.

[15] Qiao M, Bai Y H, Cao W, et al. Impact of secondary effluent from wastewater treatment plants on urban rivers: Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and derivatives [J]. Chemosphere, 2018,211:185-191.

[16] Kitazawa A, Amagai T, Ohura T. Temporal trends and relationships of particulate chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their parent compounds in urban air [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2006,40(15):4592-4598.

[17] Ma J, Horii Y, Cheng J, et al. Chlorinated and Parent Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Environmental Samples from an Electronic Waste Recycling Facility and a Chemical Industrial Complex in China [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2009,43(3):643-649.

[18] Takasuga T, Umetsu N, Makino T, et al. Role of temperature and hydrochloric acid on the formation of chlorinated hydrocarbons and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons during combustion of paraffin powder, polymers, and newspaper [J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2007,53(1):8-21.

[19] Fujima S, Ohura T, Amagai T. Simultaneous determination of gaseous and particulate chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in emissions from the scorching of polyvinylidene chloride film [J]. Chemosphere, 2006,65(11):1983-1989.

[20] Horii Y, Ok G, Ohura T, et al. Occurrence and profiles of chlorinated and brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in waste incinerators [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2008,42(6): 1904-1909.

[21] Li H Y, Gao P P, Ni H G. Emission characteristics of parent and halogenated PAHs in simulated municipal solid waste incineration [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019,665:11-17.

[22] Lei Y D, Chankal R, Chan A, et al. Supercooled liquid vapor pressures of the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [J]. Journal of Chemical and Engineering Data, 2002,47(4):801-806.

[23] Huang K, Guo J, Lin K F, et al. Distribution and temporal trend of polybrominated diphenyl ethers in one Shanghai municipal landfill, China [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2013,20(8): 5299-5308.

[24] Wang D, Zhang H J, Fan Y, et al. Electrophilic Chlorination of Naphthalene in Combustion Flue Gas [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2019,53(10):5741-5749.

[25] Fernando S, Jobst K J, Taguchi V Y, et al. Identification of the Halogenated Compounds Resulting from the 1997 Plastimet Inc. Fire in Hamilton, Ontario, using Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography and (Ultra) High Resolution Mass Spectrometry [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2014,48(18):10656-10663.

[26] Wang D L, Xu X B, Chu S G, et al. Analysis and structure prediction of chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons released from combustion of polyvinylchloride [J]. Chemosphere, 2003,53(5):495- 503.

[27] Mukai, Fujimori T, Shiota K, et al. Quantitative speciation of insoluble chlorine in E-waste open burning soil: Implications of the presence of unidentified aromatic-Cl and insoluble chlorides [J]. Chemosphere, 2019,233:493-502.

[28] Weber P, Dinjus E, Stieglitz L. The role of copper(II) chloride in the formation of organic chlorine in fly ash [J]. Chemosphere, 2001,42 (5-7):579-582.

[29] Ryu J Y. Formation of chlorinated phenols, dibenzo-p-dioxins, dibenzofurans, benzenes, benzoquinnones and perchloroethylenes from phenols in oxidative and copper (II) chloride-catalyzed thermal process [J]. Chemosphere, 2008,71(6):1100-1109.

[30] Xu Y, Yang L L, Zheng M H, et al. Chlorinated and Brominated Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons from Metallurgical Plants [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018,52(13):7334-7342.

[31] Jin R, Liu G, Zheng M, et al. Secondary Copper Smelters as Sources of Chlorinated and Brominated Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2017,51(14):7945-7953.

[32] Pinto M, Rebola M, Louro H, et al. Chlorinated Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Associated with Drinking Water Disinfection: Synthesis, Formation under Aqueous Chlorination Conditions and Genotoxic Effects [J]. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds, 2014,34(4):356-371.

[33] Koistinen J, Paasivirta J, Nevalainen T, et al. Chlorophenanthrenes, alkylchlorophenanthrenes and alkylchloronaphthalenes in kraft pulp-mill products and discharges [J]. Chemosphere, 1994,28(7): 1261-1277.

[34] Koistinen J, Paasivirta J, Nevalainen T, et al. Chlorinated Fluorenes and Alkylfluorenes in Bleached Kraft Pulp and Pulp-Mill Discharges [J]. Chemosphere, 1994,28(12):2139-2150.

[35] Xu X, Xiao R Y, Dionysiou D D, et al. Kinetics and mechanisms of the formation of chlorinated and oxygenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons during chlorination [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2018,351:248-257.

[36] Sankoda K, Toda I, Sekiguchi K, et al. Aqueous secondary formation of brominated, chlorinated, and mixed halogenated pyrene in presence of halide ions [J]. Chemosphere, 2017,171:399-404.

[37] Ohura T, Miwa M. Photochlorination of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Acidic Brine Solution [J]. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2016,96(4):524-529.

[38] Sugiyama H, Katagiri Y, Kaneko M, et al. Chlorination of pyrene in soil components with sodium chloride under xenon irradiation [J]. Chemosphere, 1999,38(8):1937-1945.

[39] Ohura T, Suhara T, Kamiya Y, et al. Distributions and multiple sources of chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the air over Japan [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019,649:364-371.

[40] Jin R, Liu G, Jiang X, et al. Profiles, sources and potential exposures of parent, chlorinated and brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in haze associated atmosphere [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2017,593:390-398.

[41] Kakimoto K, Nagayoshi H, Konishi Y, et al. Atmospheric chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in East Asia [J]. Chemosphere, 2014,111:40-46.

[42] Helm P A, Bidleman T F, Li H H, et al. Seasonal and spatial variation of polychlorinated naphthalenes and non-/mono-ortho-substituted polychlorinated biphenyls in arctic air [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2004,38(21):5514-5521.

[43] Sun J L, Ni H G, Zeng H. Occurrence of chlorinated and brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface sediments in Shenzhen, South China and its relationship to urbanization [J]. Journal of Environmental Monitoring, 2011,13(10):2775-2781.

[44] Ohura T, Sakakibara H, Watanabe I, et al. Spatial and vertical distributions of sedimentary halogenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in moderately polluted areas of Asia [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2015,196:331-340.

[45] Wang X, Kang H, Wu J. Determination of chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in water by solid-phase extraction coupled with gas chromatography and mass spectrometry [J]. Journal of Separation Science, 2016,39(9):1742-1748.

[46] Ni H G, Zeng E Y. Environmental and human exposure to soil chlorinated and brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in an urbanized region [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2012,31(7):1494-1500.

[47] Nguyen Minh T, Goto A, Takahashi S, et al. Soil contamination by halogenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from open burning of e-waste in Agbogbloshie (Accra, Ghana) [J]. Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management, 2017,19(4):1324-1332.

[48] Tan J, Lu X, Fu L, et al. Quantification of Cl-PAHs and their parent compounds in fish by improved ASE method and stable isotope dilution GC-MS [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2019, 186:109775.

[49] Sun J L, Zeng H, Ni H G. Halogenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the environment [J]. Chemosphere, 2013,90(6):1751- 1759.

[50] Wang L, Li C, Jiao B, et al. Halogenated and parent polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in vegetables: Levels, dietary intakes, and health risk assessments [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 616:288-295.

[51] Ding C, Ni H G, Zeng H. Human exposure to parent and halogenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons via food consumption in Shenzhen, China [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2013,443:857-863.

[52] Sun J L, Jing X, Chang W J, et al. Cumulative health risk assessment of halogenated and parent polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons associated with particulate matters in urban air [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2015,113:31-37.

[53] Ni H G, Guo J Y. Parent and Halogenated Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Seafood from South China and Implications for Human Exposure [J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2013,61(8):2013-2018.

[54] Bostrom C E, Gerde P, Hanberg A, et al. Cancer risk assessment, indicators, and guidelines for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the ambient air [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2002,110:451- 488.

[55] Li G, Guo F, Rao Z, et al. Simultaneous determination of sixteen polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and four derivatives in groundwater by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography [J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2017,36(6):1295-1303.

[56] Jin R, Yang L L, Zheng M H, et al. Source identification and quantification of chlorinated and brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from cement kilns co-processing solid wastes [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2018,242:1346-1352.

[57] Nishimura C, Horii Y, Tanaka S, et al. Occurrence, profiles, and toxic equivalents of chlorinated and brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in E-waste open burning soils [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2017,225:252-260.

[58] Liu Q, Xu X, Wang L, et al. Simultaneous determination of forty-two parent and halogenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons using solid-phase extraction combined with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry in drinking water [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2019,181:241-247.

[59] 王 丽,金 芬,李敏洁,等.分散固相萃取-气相色谱-串联质谱法测定蔬菜中多环芳烃及卤代多环芳烃 [J]. 分析化学, 2013,41(6): 869-875. Wang L, Jin F, Li M J, et al. Determination of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Halogenated Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Vegetable by Gas Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry [J]. Chinese Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 2013,41(6):869-875.

[60] Tillner J, Hollard C, Bach C, et al. Simultaneous determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their chlorination by-products in drinking water and the coatings of water pipes by automated solid-phase microextraction followed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry [J]. Journal of Chromatography A, 2013,1315:36-46.

[61] Sankoda K, Kuribayashi T, Nomiyama K, et al. Occurrence and Source of Chlorinated Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (CI-PAHs) in Tidal Flats of the Ariake Bay, Japan [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2013,47(13):7037-7044.

[62] Sun P, Weavers L K, Taerakul P, et al. Characterization of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) on lime spray dryer (LSD) ash using different extraction methods [J]. Chemosphere, 2006,62(2):265-274.

[63] Yusa V, Pardo O, Pastor A, et al. Optimization of a microwave- assisted extraction large-volume injection and gas chromatography- ion trap mass spectrometry procedure for the determination of polybrominated diphenyl ethers, polybrominated biphenyls and polychlorinated naphthalenes in sediments [J]. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2006,557(1/2):304-313.

[64] 李 丹,周明辉,刘莹峰,等.微波萃取/GC-MS法对电子电气产品中多氯萘的测定 [J]. 分析测试学报, 2010,29(1):43-45,50. Li D, Zhou M H, Liu Y F, et al. Determination of polychlorinated naphthalenes in electrical and electronic products by microwave extraction and GC-MS method [J]. Journal of Instrumental Analysis, 2010,29(1):43-45,50.

[65] 刘春娟.微波萃取技术应用及其研究进展 [J]. 广东化工, 2008,3: 53-55,58. Liu C J. The application and research development of microwave assisted extraction [J]. Guangdong Chemical Industry. 2008,3:53- 55,58.

[66] Han Y, Ren L, Xu K, et al. Supercritical fluid extraction with carbon nanotubes as a solid collection trap for the analysis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their derivatives [J]. Journal of Chromatography A, 2015,1395:1-6.

[67] Wiater-Protas I, Van B B, Parczewski A. Rapid extraction and clean-up of PCNs and PCDFs from soil samples using SFE-LC with solid phase carbon trap. Comparison with other methods [J]. Chemia Analityczna, 2002,47(5):659-667.

[68] Librando V, Hutzinger O, Tringali G, et al. Supercritical fluid extraction of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from marine sediments and soil samples [J]. Chemosphere, 2004,54(8):1189-1197.

[69] Shimmo M, Anttila P, Hartonen K, et al. Identification of organic compounds in atmospheric aerosol particles by on-line supercritical fluid extraction-liquid chromatography-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry [J]. Journal of Chromatography A, 2004,1022(1/2): 151-159.

[70] Gevao B, Harner T, Jones K C. Sedimentary record of polychlorinated naphthalene concentrations and deposition fluxes in a dated Lake Core [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2000,34(1):33-38.

[71] Vandermarken T, Gao Y, Baeyens W, et al. Dioxins, furans and dioxin-like PCBs in sediment samples and suspended particulate matter from the Scheldt estuary and the North Sea Coast: Comparison of CALUX concentration levels in historical and recent samples [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018,626:109-116.

[72] Li H R, Zhou L, Ren M, et al. Levels, profiles and gas-particle distribution of atmospheric PCDD/Fs in vehicle parking lots of a South China metropolitan area [J]. Chemosphere, 2014,94:128-134.

[73] Jin R, Liu G, Zheng M, et al. Congener-specific determination of ultratrace levels of chlorinated and brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in atmosphere and industrial stack gas by isotopic dilution gas chromatography/high resolution mass spectrometry method [J]. Journal of Chromatography A, 2017,1509:114-122.

[74] Subedi B, Aguilar L, Robinson E M, et al. Selective pressurized liquid extraction as a sample-preparation technique for persistent organic pollutants and contaminants of emerging concern [J]. Trac-Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2015,68:119-132.

[75] Masuda M, Wang Q, Tokumura M, et al. Simultaneous determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their chlorinated derivatives in grilled foods [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2019,178:188-194.

[76] 莫李桂,马盛韬,李会茹,等.气相色谱/三重四极杆串联质谱法检测土壤中氯代多环芳烃和溴代多环芳烃 [J]. 分析化学, 2013,41(12): 1825-1830. Mo L G, Ma S T, Li H R, et al. Determination of chlorinated- and brominated- polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soil samples by gas chromatography coupled with triple quadrupole mass spectrometry [J]. Chinese Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 2013,41(12):1825-1830.

[77] 原文婷,高占啟,孙 成.土壤中6种氯代多环芳烃测定方法的建立及应用 [J]. 环境监控与预警, 2015,7(6):13-17,37. Yuan W T, Gao Z Q, Sun C. Method development and application for the determination of chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soil [J]. Environmental Monitoring and Forewarning, 2015,7(6):13- 17,37.

[78] Qiao M, Cao W, Liu B C, et al. Simultaneous detection of chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry [J]. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 2017,9(13):3465-3473.

[79] Falandysz J, Strandberg L, Bergqvist P A, et al. Polychlorinated naphthalenes in sediment and biota from the Gdansk Basin, Baltic Sea [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 1996,30(11):3266-3274.

[80] Yang L, Wang S, Peng X, et al. Gas chromatography-Orbitrap mass spectrometry screening of organic chemicals in fly ash samples from industrial sources and implications for understanding the formation mechanisms of unintentional persistent organic pollutants [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019,664:107-115.

[81] Fan Y, Zhang H, Wang D, et al. Simultaneous determination of chlorinated aromatic hydrocarbons in fly ashes discharged from industrial thermal processes [J]. Analytical Methods, 2017,9(35): 5198-5203.

[82] Manzano C, Hoh E, Simonich S L M. Improved separation of complex polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon mixtures using novel column combinations in GCxGC/ToF-MS [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2012,46(14):7677-7684.

[83] Ieda T, Ochiai N, Miyawaki T, et al. Environmental analysis of chlorinated and brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography coupled to high-resolution time-of-flight mass spectrometry [J]. Journal of Chromatography A, 2011,1218(21):3224-3232.

[84] Wang J, Fan Y, Lu X, et al. Solid-phase extraction combined with HPLC for the determination of chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in tap water samples [J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2018,37(9):1987-1993.

[85] Moukas A I, Thomaidis N S, Calokerinos A C. Novel determination of polychlorinated naphthalenes in water by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry with atmospheric pressure photoionization [J]. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 2016,408(1):191-201.

[86] Teng M, Jin J, Fu Q, et al. Selective separation of polychlorinated naphthalene (PCNs), hexabromocyclododecanes (HBCDs) and tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA) in soil matrices [J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2013,58(4/5):500-506.

[87] Chen Z, Xie H, Liu J, et al. Simultaneous quantification of phencynonate and its active metabolite N-demethyl phencynonate in human plasma using liquid chromatography and isotope-dilution mass spectrometry [J]. Drug Testing and Analysis, 2015,7(9):843-847.

[88] Gao Z Y, Jiang W S, Sun D, et al. Chlorination for efficient identification of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry [J]. Talanta, 2010,81(1/2):48-54.

致谢:感谢评审专家和责任编辑对本文的细致点评和宝贵建议,同时感谢华南师范大学环境学院陈长二教授在本文英文修改上提供的热心帮助和支持!

A review of chlorinated/brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the environment and human: Sources, analysis methods and pollution characteristics.

LIU Ming-yang1,4, LI Hui-ru2,3, SONG Ai-min1,4, HU Jian-fang1, SHENG Guo-ying1, PENG Ping-an1,4*

(1.State Key Laboratory of Organic Geochemistry and Guangdong Key Laboratory of Environmental Protection and Resources Utilization, Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510640, China;2.SCNU Environmental Research Institute, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Chemical Pollution and Environmental Safety & MOE Key Laboratory of Theoretical Chemistry of Environment, South China Normal University, Guangzhou 510006, China;3.School of Environment, South China Normal University, Guangzhou 510006, China;4.University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China)., 2021,41(4):1842~1855

Chlorinated/brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (Cl/Br-PAHs) were a class of emerging persistent toxic contaminants that demonstrating similar chemical structures and carcinogenicities with dioxins and PAHs. Their behaviors, fates, and potential risks in environments were of great concern. This study retrieved the Web of Science Database with the topics including "Cl-PAH*" OR"Br-PAH*" OR"H-PAH*" OR"chlorinated PAH*" OR"brominated PAH*" OR"halogenated PAHs" OR"chlorinated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon*"OR"brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon*"OR"halogenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon*", and reviewed the research progress of the sources, pollution characteristics and analysis methods of Cl/Br-PAHs focusing on the environmental matrix and human beings. The results showed that 225 papers in total within this topic were published by Jan. 2021. The existing findings showed that: Cl/Br-PAHs were mainly generated from thermal processes such as waste incineration, vehicle exhaust, metal smelting, electronic waste recycling, etc., as well as some photochemical processes; So far, Cl/Br-PAHs were found ubiquitous in various environments worldwide, and demonstrated persistence, long-distance transportability and bioavailability; It was documented that Cl/Br-PAHs had similar or stronger toxicity compared to their parent PAHs. However, their formation mechanisms and environmental behaviors were still unclear; An effective and precise analytical method was still unavailable, leading to very limited reports on Cl/Br-PAH compounds in environments and the overall research area on this topic was still in its infant stage. Based on the current research status and knowledge gaps of Cl/Br-PAHs, more attention should be paid to their high-throughput and precise analytical methods, emission fingerprints, environmental behaviors, and potential risks in the future.

chlorinated/brominated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons;aromatic receptor effect;gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer

X592

A

1009-6923(2021)04-1842-14

刘明洋(1996-),男,河南信阳人,中国科学院广州地化所硕士研究生,主要从事环境有机污染物方面的研究.

2020-08-16

广州市科技计划项目(201707020028);广东省自然科学基金资助项目(2018A030313904);广东省科技项目(2017B030314057)

* 责任作者, 研究员, pinganp@gig.ac.cn