Competing endogenous RNAs in lung cancer

2021-04-22MeilianZhaoJianguoFengLilingTang

Meilian Zhao, Jianguo Feng, Liling Tang

1Key Laboratory of Biorheological Science and Technology, Ministry of Education, College of Bioengineering, Chongqing University, Chongqing 400044, China; 2Department of Anesthesiology, The Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University, Luzhou 646000, China

ABSTRACT Competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) containing microRNA response elements can competitively interact with microRNA via miRNA response elements, which can combine non-coding RNAs with protein-coding RNAs through complex ceRNA networks. CeRNAs include non-coding RNAs (long non-coding RNAs, circular RNAs, and transcribed pseudogenes) and protein-coding RNAs (mRNAs). Molecular interactions in ceRNA networks can coordinate many biological processes; however, they may also lead to ceRNA network imbalance and thus contribute to cancer occurrence when disturbed. Recent studies indicate that many dysregulated RNAs derived from lung cancer may function as ceRNAs to regulate multitudinous biological functions for lung cancer, including tumor cell proliferation, apoptosis, growth, invasion, migration, and metastasis. This study therefore reviewed the research progress in the field of non-coding and protein-coding RNAs as ceRNAs in lung cancer, and highlighted validated ceRNAs involved in biological lung cancer functions. Furthermore, the roles of ceRNAs as novel prognostic and diagnostic biomarkers were also discussed. Interpreting the involvement of ceRNAs networks in lung cancer will provide new insight into cancer pathogenesis and treatment strategies.

KEYWORDS CeRNA; lung cancer; biological functions; biomarker

Introduction

Lung cancer has the highest mortality rate of all cancers globally, accounting for about 10%-20% of total cancer deaths. Due to high metastasis, the 5 year survival is approximately 18%. Lung cancer is a molecularly heterogeneous cancer and understanding its biology is crucial for the development of effective therapies. The World Health Organization divides lung cancer into two main types based on its biological characteristics and clinical treatment practices: small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)1. The most common NSCLCs are lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and lung squamous carcinoma (LUSC). The proportion of NSCLC in all lung cancers is 80%-85%. NSCLC is the leading cause of cancer-related death, causing about 1.6 million deaths since 20122. Lung cancer is similar to most malignancies in that it has distinct molecular characteristics, and is composed of subpopulations of cells, or clones, resulting in intratumoral heterogeneity3. LUAD is the most heterogeneous and aggressive among lung cancer subtypes, and has a very high tumor mutation burden associated with increased postsurgical relapse possible in treated patients4. This indicates that there is a greater metastases propensity during early tumor development related to increased intratumoral heterogeneity. SCLC accounts for approximately 14% of all lung cancers, and has some of the most representative clinical characteristics and distinctive malignancies in the entire field of oncology. SCLC is an aggressive high grade malignant cancer associated with a high growth rate and widespread metastases during early tumor development, which contributes to the extremely poor prognoses of cancer patients3. Currently, the primary treatment methods for lung cancer include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and targeted therapy. Therapeutic approach options depend on several factors, including the cancer grade and stage5. In spite of the progress made in diagnosing and treating tumors in the past 25 years, patients have a low survival due to the failure and/or limitations of chemotherapy6,7. This problem forces people to constantly seek new diagnoses and therapy strategies. Therefore, in-depth institutional research and novel therapeutic target discovery are presently the major emphases of cancer research.

With the development of high-throughput sequencing and constant updating of algorithms, large amounts of non-encoded RNAs have been found to perform multitudinous biological functions in humans, and are involved in the generation and development of tumors4. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a family of regulatory, endogenously expressed, small non-coding RNA molecules that control mRNA expression, primarily by binding to the 3′-untranslated regions (3′-UTRs)8. MiRNAs play a vital role as tumor suppressors or oncogenes by silencing or activating target gene expression, which has differential expression patterns in cancer9. There are more than 500 miRNA genes that can recognize and specifically bind their targets through miRNA response elements (MREs) in the human genome. MREs are normally located in coding sequences, especially in the 3′-UTRs of various types of RNAs, such as circRNAs, mRNAs, lncRNAs, and transcribed pseudogenes10. In theory, any RNA transcriptome containing miRNA-binding sites has the ability to combine specifically with miRNAs, which can act as ceRNAs transcribers, including protein-coding mRNAs and non-coding RNAs (ncRNA). For example, long non-coding RNAs transcribe pseudogenes, and circular RNAs can compete with protein-coding mRNAs to bind shared miRNAs by acting as ceRNAs or natural microRNA sponges. Post-transcriptional regulators are important for gene expression11-13. The ceRNA studies have revealed a new mechanism for RNA-RNA interactions, communication, and co-regulation, in which miRNAs can affect gene expression by binding to mRNAs. Additionally, ceRNAs can competitively interact with miRNAs via MREs. For example, Kumar et al.14discovered a novel protein-coding gene, HMGA2, that exerts its effects largely independent of its protein coding function. HMGA2 functions as a ceRNA for the let-7 miRNA family to promote lung cancer progression. Therefore, it is critical and significant to recognize and elucidate the regulatory mechanisms of lung cancer ceRNA networks and their impacts on cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment, which in turn has an impact on human development and disease.

In this review, we focused on research progress involving non-coding and protein-coding RNAs as ceRNAs in lung cancer, and highlighted validated ceRNAs involved in lung cancer biological functions. Furthermore, the role of ceRNAs as novel prognosis and diagnosis biomarkers was also discussed.

The ceRNA crosstalk in lung cancer

The ceRNA hypothesis was formally proposed by Salmena et al.15in 2011. It describes a previously unknown large-scale regulatory mechanism regulating gene expression via transcriptomes. MiRNAs not only affect the transcription and stability of RNAs at the post-transcriptional level through binding to target genes, but RNAs in turn can also influence miRNAs15-17. This original novel pattern is named the “RNA→miRNA→RNA” interplay. The miRNAs act as negative or positive regulators of gene translation, that decrease/enhance the stability of target RNAs or limit/promote their expression efficiencies and levels. RNA transcripts contain the same MREs on their 3′-UTRs, which can act as ceRNAs to communicate and regulate their expression levels by competitively binding the same sequences of miRNAs18. The conditions needed for the formation of a ceRNA crosstalk mechanism remain unknown. Recent studies have shown that the effect of ceRNA activity depends on a series of factors, including the relative concentration of miRNAs/ceRNAs, changes of RNA 3′-UTRs, RNA editing, and RNA binding proteins (RBPs)13,19. First, the relative abundances of the ceRNAs and the target miRNAs are clearly important, because too much or too little ceRNA or target miRNA will reduce ceRNA-miRNA competition efficiency19. Second, the combination effectiveness of a ceRNA for microRNA molecules may be decided by its subcellular localization and interaction with RBPs12,20. If any of these factors are altered, ceRNA network imbalance can occur, and thus contribute to cancer occurrence and development. Recent studies have shown that an increasing number of ceRNAs were found through bioinformatics technology, which plays an important role in lung cancer studies. Interpreting the ceRNA network as it pertains to cancer can therefore provide new insights into cancer pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies.

The lncRNAs as ceRNAs

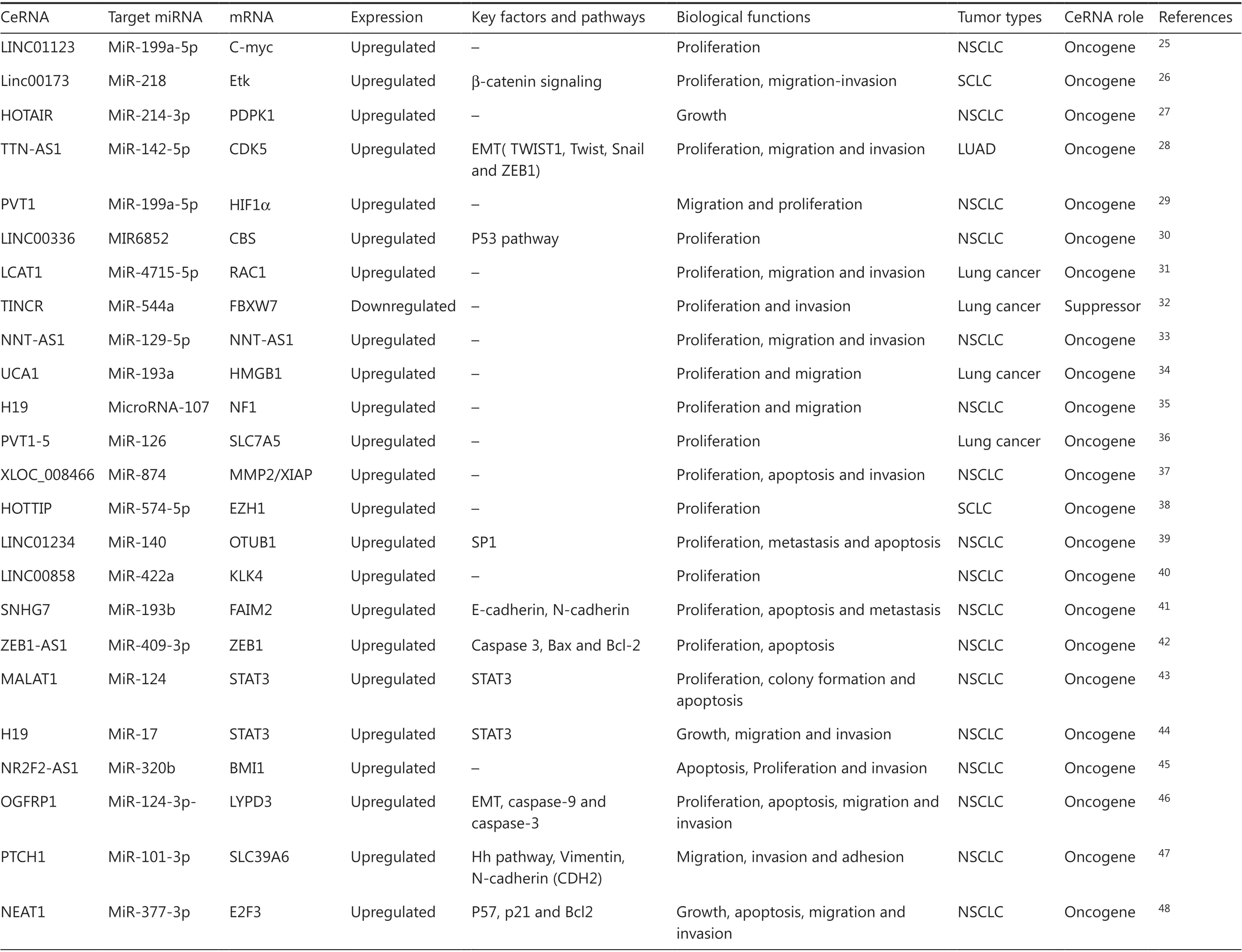

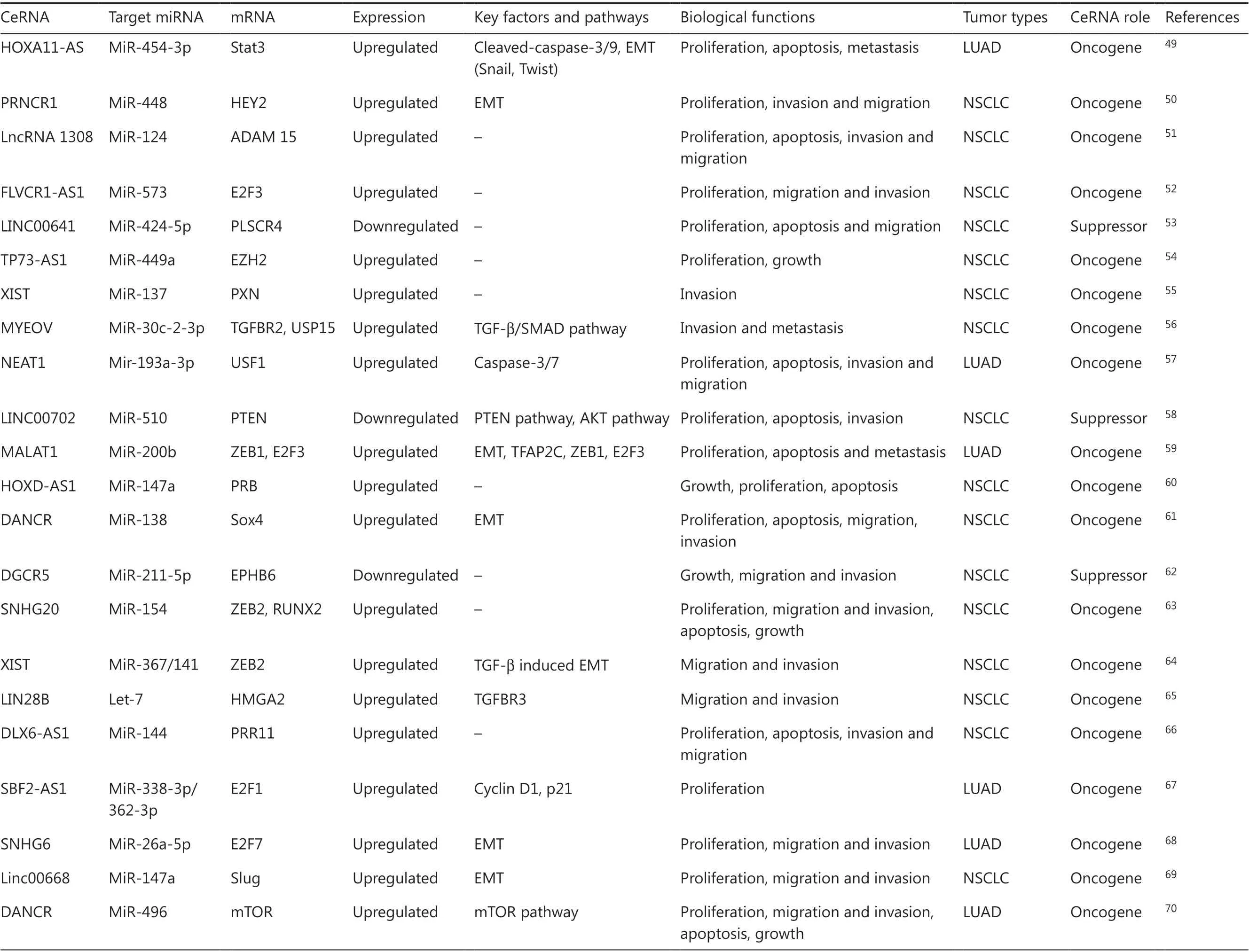

There are about 20,000 protein-coding genes, which only account for < 2% of the total genome sequence; nevertheless, at least 90% of genes are actively transcribed into ncRNA. This implies that lncRNAs can play significant regulatory roles in biological processes. The lncRNAs are a type of ncRNA molecule defined by a lack of protein-coding potential (often determined computationally) and are commonly defined as being longer than 200 nucleotides. Evidence suggests that lncRNAs are aberrantly expressed in various types of cancer cells and contribute to the initiation and development of several common hallmarks of cancer21-23. In general, lncRNAs can regulate gene expression levels at different stages and through different pathways, including chromatin modification, transcription, and post-transcription. For chromatin modification, lncRNAs induce chromatin formation in a specific genomic locus by interacting with chromatin remodeling complexes, resulting in decreased gene expression. Moreover, lncRNAs regulate promoters or interact with RNA-binding proteins and transcriptional factors to modulate gene transcription levels. Based on these features, lncRNAs are involved in many important biological phenomena, such as gene imprinting, transcriptional enhancement, chromosome looping, and antisense regulation24. The lncRNAs exert regulatory functions as ceRNAs by competitively binding to shared sequences of miRNAs and influencing the expression levels of their downstream target genes (mRNA). The lncRNAs can form lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA interactions, which are called ceRNA networks. Recent studies revealed that lncRNAs act as ceRNAs to participate in lung cancer development by competing with miRNAs and protein-coding mRNAs to modulate biological functions. The lncRNA-mediated competitive RNA crosstalk in lung cancer progression has been identified and is shown in Table 1.

The circRNA as ceRNAs

Evidence presented in 1993 indicates that junctions of misspliced ets-1 exons lead to the formation of circular RNA ( circRNA) molecules, which is the first case of circular transcripts being processed from nuclear pre-mRNA in eukaryotes93. The circRNAs are defined as a large class of non-coding RNAs that are generated by canonical splicing machinery; an upstream splice site is covalently linked to a downstream splice site during backsplicing. The circRNAs are closed and have no open linear tails, making them insensitive to exonucleases. This suggests that circRNAs are very stable, which might reflect their important non-coding functions. In addition, circRNAs have been related to and participated in many human diseases, including diabetes mellitus, neurological disorders, chronic inflammatory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer94-97. In addition, they may accumulate during the onset of illness. CircRNAs are abundant and evolutionarily conserved. Additionally, some circRNAs exert important biological functions by acting as ceRNA, which contain many miRNA competing binding sites to regulate protein synthesis and function. Hence, circRNAs exert tumor suppressive or oncogenic functions by acting as miRNA sponges to combine multiple diverse miRNAs, rather than a particular miRNA. Higher circRNA expression levels may therefore cooperatively function to sponge numerous miRNAs and affect the progression of lung cancer (Table 2).

Pseudogenes as ceRNAs

Pseudogenes, defined as dysfunctional transcripts of protein-coding genes, represent a particular type of lncRNA once thought to be “genomic junk,” and were considered without any biological function114,115. However, recent improvements of the genome project have revealed that many pseudogenes have transcriptional activities. Furthermore, pseudogenes can exert a positive effect because they are stable. However, their dysregulation can contribute to the occurrence of diseases, and their disordered expressions contribute to the development and progression of multiple cancers116. Increasing evidence has shown that pseudogenes play key roles in tumor suppression or oncogenesis. Despite the abundance of pseudogenes identified in human cancers or other diseases, the pathophysiological roles of pseudogenes in lung cancer remain poorly understood.

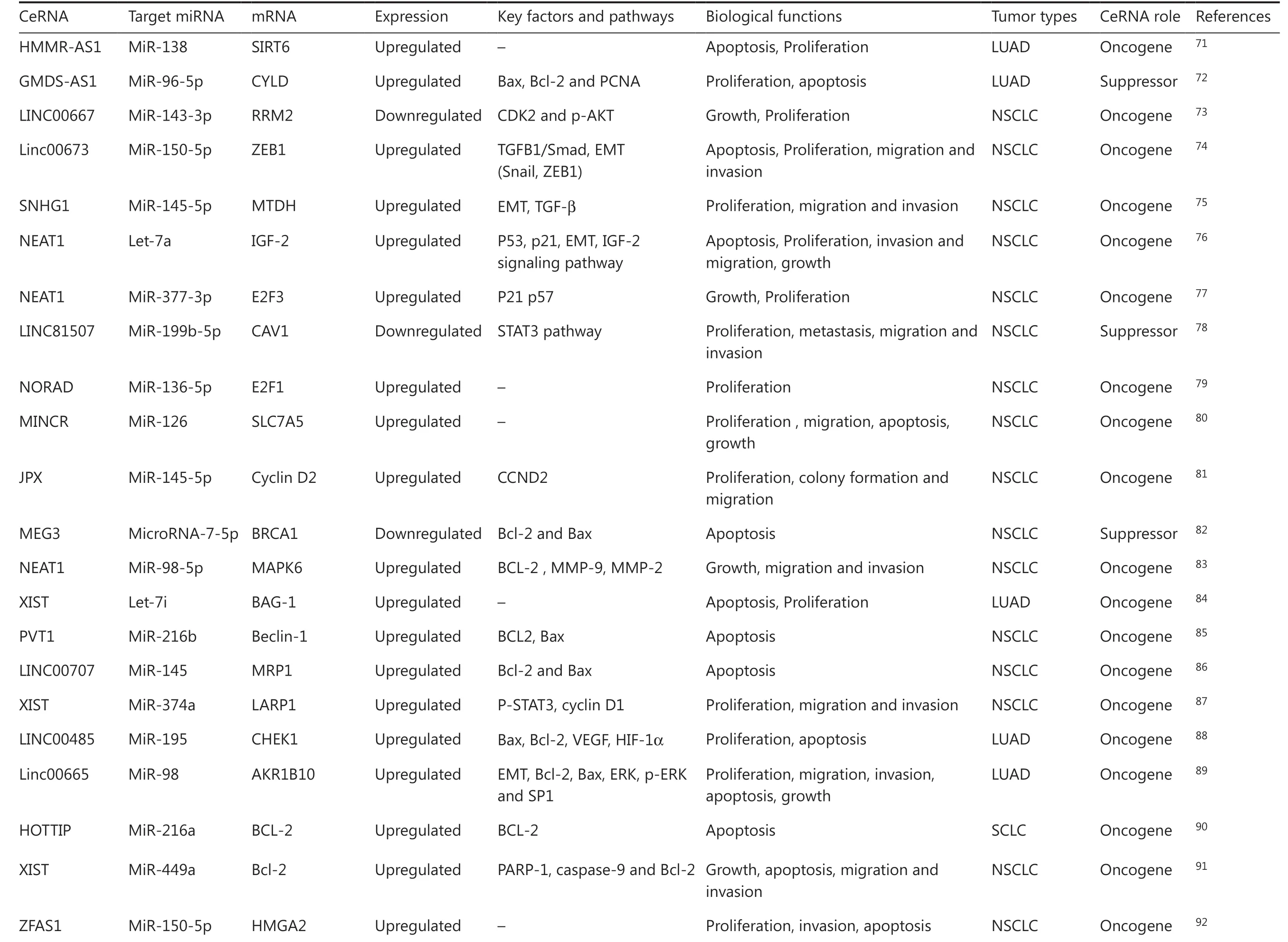

The mRNAs as ceRNAs

Researchers currently are very interested in the effects of non-coding RNAs. Nevertheless, coding transcripts (mRNA) are more abundant and show the highest conservation of miRNA binding sites. Previous studies have shown that the particular 3′-UTR of a mRNA could act as a ceRNA to regulate the activity of endogenous miRNAs, which then may affect the expression levels of downstream mRNAs117,118. Recent studies also showed that mRNAs serve as miRNA sponges, which exert the most influence during lung cancer progression (Table 3).

The ceRNAs function in lung tumor signaling pathways and biological processes

In recent years, the important roles of ceRNA interactions during cancer initiation and progression processes have been accepted. An increasing number of ceRNAs has been reported to be involved in the cellular signaling pathways of lung cancer,such as in β-catenin signaling, the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, the PTEN pathway, the IGF-2 signaling pathway, Wnt signaling, the STAT3/p-STAT3 pathway, and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling (Tables 1-3). Furthermore, ceRNAs competing with miRNAs are involved in the biological functions of lung cancer, such as in tumor cell proliferation, apoptosis, growth, cell cycle, invasion, migration, and metastasis (Tables 1-3). Some ceRNAs have also been found to be dysregulated in lung tumor tissues, playing tumor-oncogenic or tumor-suppressor roles. In this review, we therefore mainly discussed validated ceRNAs and their biological functions in lung cancer.

Table 1 Overview of long noncoding RNAs as competing endogenous RNAs in lung cancer

Table 1 Continued

Table 1 Continued

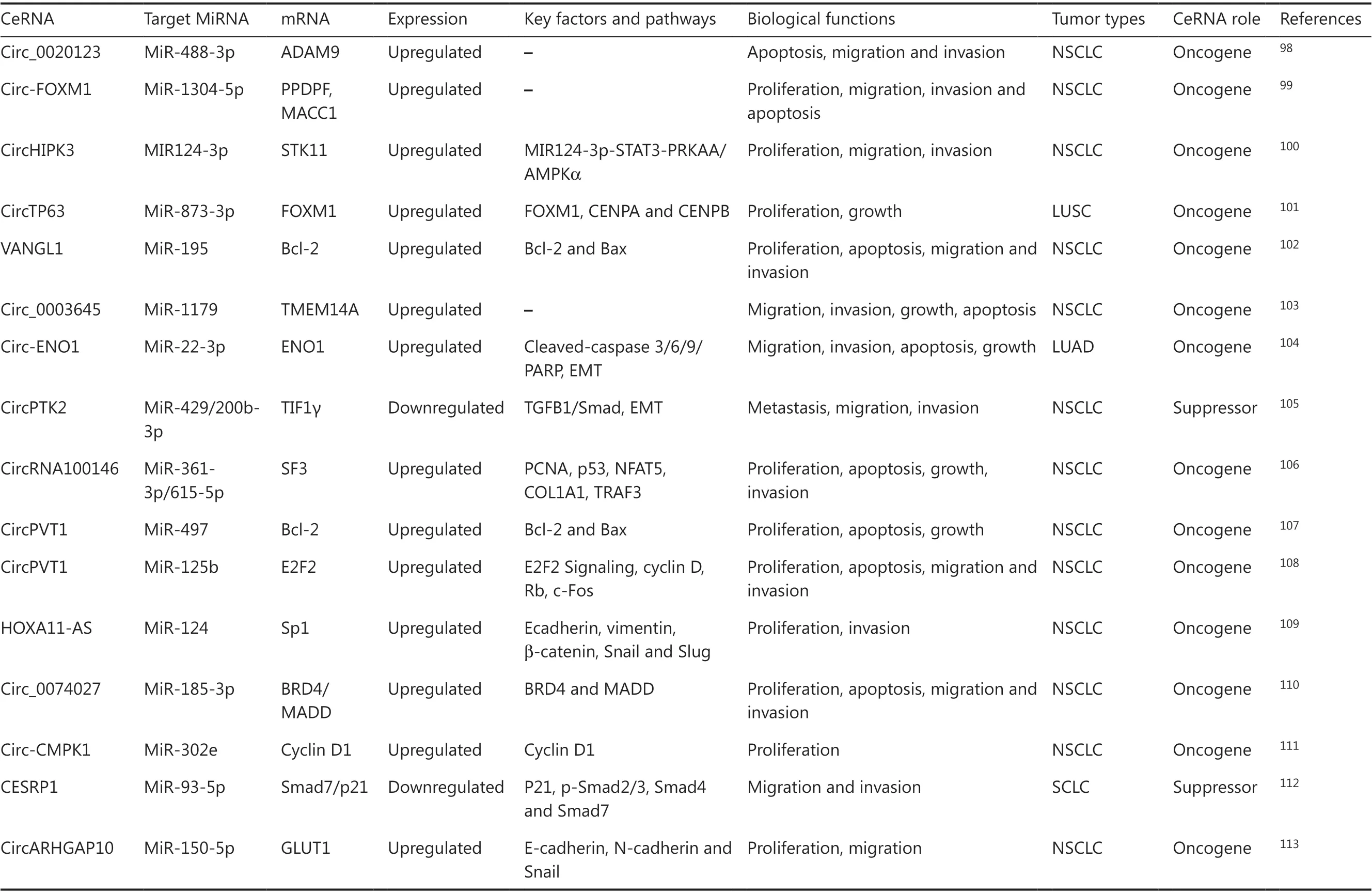

Table 2 Overview of circular (circ)RNAs as competing endogenous RNAs in lung cancer

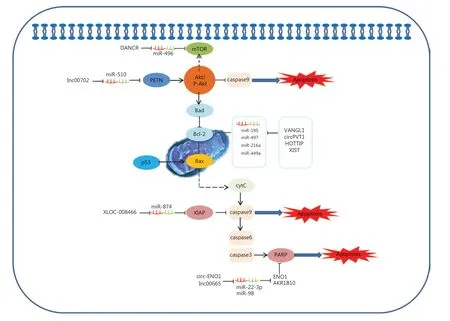

Table 3 Overview of mRNAs as competing endogenous RNAs in lung cancer

The ceRNAs and the signaling pathways involved in lung cancer cell proliferation

Cellular metabolism is the basis of all biological activities123. Compared with normal differentiated cells, most cancer cells rely primarily on aerobic glycolysis to generate a large amount of energy during cellular processes. Cell growth and proliferation must be regulated124,125. In addition, the capacity of unlimited multiplication is a typical characteristic of tumor cells. Cell proliferation requires the accumulation of an intracellular biomass, such as proteins and lipids. It is therefore essential for cellular replication and division to produce proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. Notably, cancer is characterized by abnormal proliferation resulting from aberrant expression of various cell cycle proteins; therefore, cell cycle regulators are considered to be vital factors in tumor proliferation126. Studies have reported that ceRNAs are involved in lung tumor proliferation.

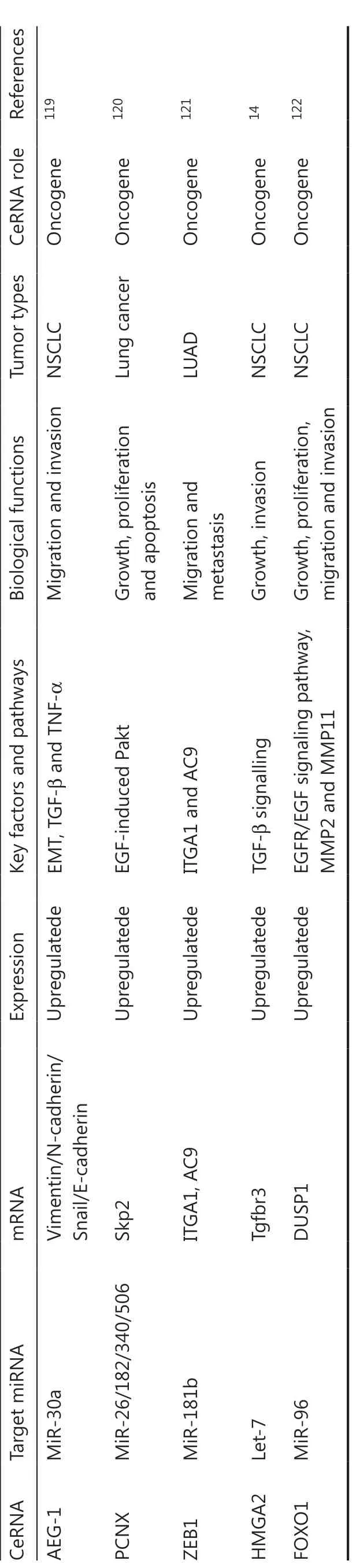

STAT3 functions as a significant protein in the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, and has been identified as having a significant role in tumorigenesis127,128. In addition, STAT3/p-STAT3 plays an important role in regulating multiple cell processes, such as cell proliferation129. Some lncRNAs function as ceRNAs to competitively bind shared sequences of miRNAs and regulate mRNA generation and function, which has been reported to participate in cell proliferation via inactivating the STAT3 signaling pathway in lung cancer (Figure 1)43,44,49,78,87. LINC81507 is decreased in NSCLC and acts as a ceRNA to sponge miR-199b-5p by regulating the CAV1/STAT3 signaling pathway. This suggests that LINC81507 serves as a tumor suppressor for cell proliferation in NSCLC78.

Figure 1 Competing endogenous RNAs (CeRNAs) and the signaling pathways involved in lung cancer cell proliferation. The AKT pathway and STAT3/p-STAT3 signaling pathways play an important role in the proliferation of lung cancer cells; PCNX, NEAT1, LINC00702, LINC00667, HOXA11-AS, MALAT1, H19, Linc81507, and XIST function as ceRNAs and are involved in these signaling pathways. In addition, the cell cycle is considered an important factor in tumor proliferation. SBF2-AS1, GMDS-AS1, cESRP1, OIP5-AS1, circ-CMPK1, JPX, circPVT1, NEAT1, LINC00667, circ-100146, and LCAT1 act as ceRNAs to regulate cell proliferation by targeting cell cycle regulators.

It is well-known that Akt kinase is commonly activated in human cancers130-132. Some ceRNAs impact cell proliferation by targeting the protein kinase B (AKT) signaling pathway and β-catenin signaling during lung cancer progression26,58,73,120. Skp2, as a unique E3 ligase of Akt, has been reported to trigger K63-linked Akt ubiquitination and to also be involved in Akt phosphorylation and activation in response to EGF stimulation133,134. The EGF-induced Akt phosphorylation affected PCNX, which functions as a ceRNA to target oncogenic Skp2120. Research results also indicate that Linc00702 may act as a ceRNA for miR-510, and may inhibit proliferation of NSCLC cells via activating PTEN, while PTEN’s downstream target, p-AKT is significantly altered58. IGFs (IGF1 and IGF2) are capable of promoting cellular proliferation by stimulating phosphorylation of MAPK and Akt. IRS1 is the substrate for the IGF receptor, and phosphorylation of IRS1 is mediated by IGF-2 to subsequently activate the Akt signaling pathway134,135. LncRNA NEAT1 acts as a let-7a sponge to facilitate proliferation via the IGF2/AKT/MAPK signaling pathway in NSCLC (Figure 1)76.

Cell cycle regulators are considered important factors in tumor proliferation. Some circRNAs regulate cell proliferation by targeting cell cycle regulators. P21 is a well-known inhibitor of cell cycle progression, which can arrest cells in G1/S and G2/M phases by inhibiting CDK4,6/cyclin-D and CDK2/cyclin-E (cell cycle-related proteins), respectively136-138. It is believed that p21 acts by suppression of E2F (E2F1, E2F2, and E2F3) activity to regulate cell growth. In brief, p21 interacts with these factors and disrupts their interactions to inhibit the cell cycle and cell proliferation progression. SBF2-AS1, a lncRNA upregulated in NSCLC, could increase E2F1 expression through competitively binding with miR-338-3p/miR-362-3p. During tumor proliferation, this results in decreased p21 gene expression and increased cyclinD167. E2F3 is a core oncogene involved in promoting NSCLC proliferation progression. However, NEAT1 as a ceRNA for hsa-miR-377-3p, could lead to the derepression and functional incapacitation of its endogenous target, E2F348. Furthermore, E2F3 overexpression reverses the inhibitory efficiency of miR-377-3p in downregulating protein levels of E2F3, CDK4, cyclinD1, and cyclinD2, and also reverses the favorable efficiency of miR-377-3p in the upregulation of p21 and p57 protein levels48. Although the functions of E2Fs are most commonly relevant to and involved in cell cycle regulatory mechanisms, studies have shown that non-classical roles for E2Fs beyond proliferation regulation are largely associated with cancer. The activation of all E2F activators (E2F1, E2F2, and E2F3) can lead to uncontrolled proliferation (Figure 1)136. For example, some lncRNAs, such as NEAT1, FLVCR1-AS1, and MALAT1, function as ceRNAs, which positively regulate E2F3 expression through respectively inhibiting miR-377-3p, miR-573, and miR-200b during NSCLC cell proliferation48,52,59. LncRNAs SBF2-AS1 and NORAD regulate E2F1 expression by binding specific miR-338-3p/362-3p or miR1365p, respectively, to promote NSCLC cell proliferation67,79. In addition, circRNA circPVT1 enhances proliferation through sponging miR-125b and activating E2F2 signaling in NSCLC108. Activation of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) and dysregulation of the cell-cycle mechanism can promote tumor cell-cycle progression, which in turn can stimulate uncontrolled tumor cell proliferation, a key characteristic of cancer139. A further investigation showed that OIP5-AS1 functioned as a ceRNA of miR-378a-3p. Its inactivation caused a decrease of proliferation-associated proteins, CDK4 and CDK6, and inhibited tumor cell proliferation in NSCLC cells140.

On a Sunday when I went to church alone, Betty handed me a small piece of paper and asked me to read it when I had time. On the slip of paper she had written, “Here are some phrases to think about over an egg enjoyed from an egg cup.”

The ceRNAs and signaling pathways involved in lung cancer cell apoptosis

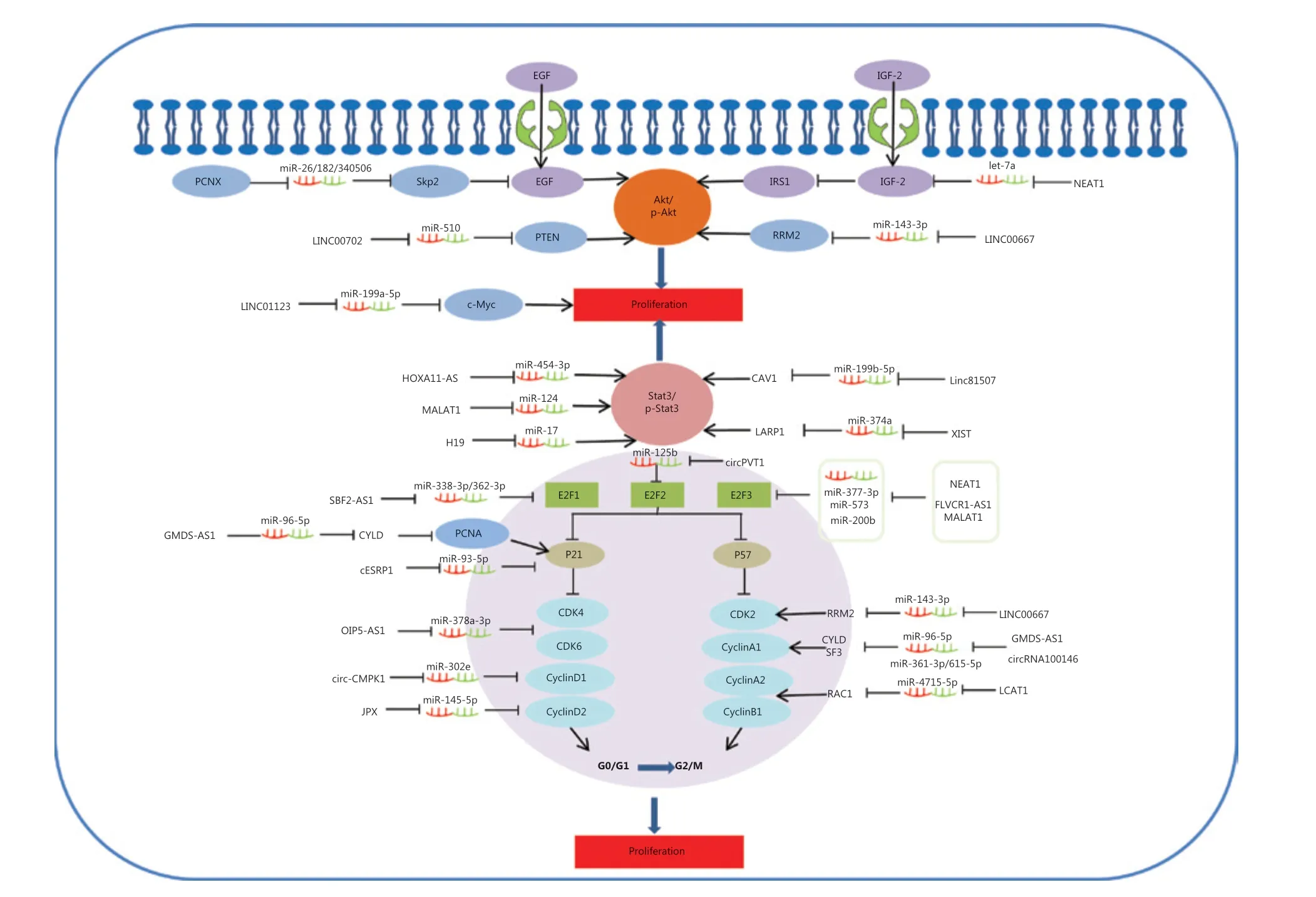

The ability of cancer cells to suppress apoptosis is critical for carcinogenesis141. Recent advances reveal that potential ceRNAs may regulate cell apoptosis, and can thus be used to predict the effects of progression and treatments in response to apoptosis in lung cancer. In mitochondria, the BCL-2 protein family determines the commitment of cells to an intrinsic apoptotic response. This protein family also plays a pivotal role in controlling programmed cell death by regulating intracellular proapoptotic and anti-apoptotic signals142,143. There are four characterized ceRNAs, VANGL1, circPVT1, HOTTIP, and XIST, which may function as ceRNAs to regulate the expression level of the apoptosis-related protein, Bcl-2 (Figure 2)90,91,102,107. Bad inhibits the pro-survival Bcl-2-like proteins, and thereby enables activation of the pro-apoptotic effector Bax, which then disrupts the outer mitochondrial membrane. The cytochrome C (cytC) released from the mitochondria promotes caspase9 activation, whereas E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase XIAP (the X-linked inhibitor of an apoptosis protein) blocks the expression of caspase9144,145. Caspase9 can activate procaspase3 and procaspase6, resulting in cell apoptosis. XLOC_008466 functions as an oncogene in NSCLC by directly binding to the miR-874-MMP2/XIAP axis, which indicates that XLOC_008466 may act as a ceRNA to affect cell apoptosis37. Both Circ-ENO1 and lnc00665 are upregulated in lung cancer, and act as ceRNAs to prohibit apoptosis. Silencing circ-ENO1 and lnc00665 caused PARP levels to decline, and elevated levels of cleaved-caspase3, cleaved-caspase6, and cleaved-caspase989,104. The tumor suppressor gene, p53, is the most frequently mutated gene in all human tumor cells. The p53 tumor-suppressor pathway regulates hundreds of genes that are involved in multiple biological processes, including cell cycle arrest, senescence, and apoptosis146,147. Activation of the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3-K)/protein kinase B (AKT) pathway is also associated with cell apoptosis. LINC00702 is an upstream regulator of the miR-510-PTEN axis, and acts via activating the Akt signaling pathway to regulate lung cancer apoptosis58.

The ceRNAs and signaling pathways involved in lung cancer cell invasion and migration

Figure 2 Competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) and the signaling pathways involved in lung cancer cell apoptosis. The BCL-2 protein family of mitochondrial proteins plays a pivotal role in regulating programmed cell death by controlling proapoptotic and anti-apoptotic intracellular signals; VANGL1, circPVT1, HOTTIP and XIST function as miRNA sponges to regulate the expression of apoptosis-related protein Bcl-2. The cytC released from mitochondria promotes caspase9 activation, whereas XIAP blocks the expression of caspase9. Caspase9 then activates procaspase3 and procaspase6, resulting in cell apoptosis. XLOC_008466 functions as an oncogene in non-small cell lung cancer by directly binding to the miR-874-MMP2/XIAP axis to affect cell apoptosis. Both Circ-ENO1 and lnc00665 are upregulated in lung cancer, and act as ceRNAs to prohibit apoptosis by inhibiting PARP.

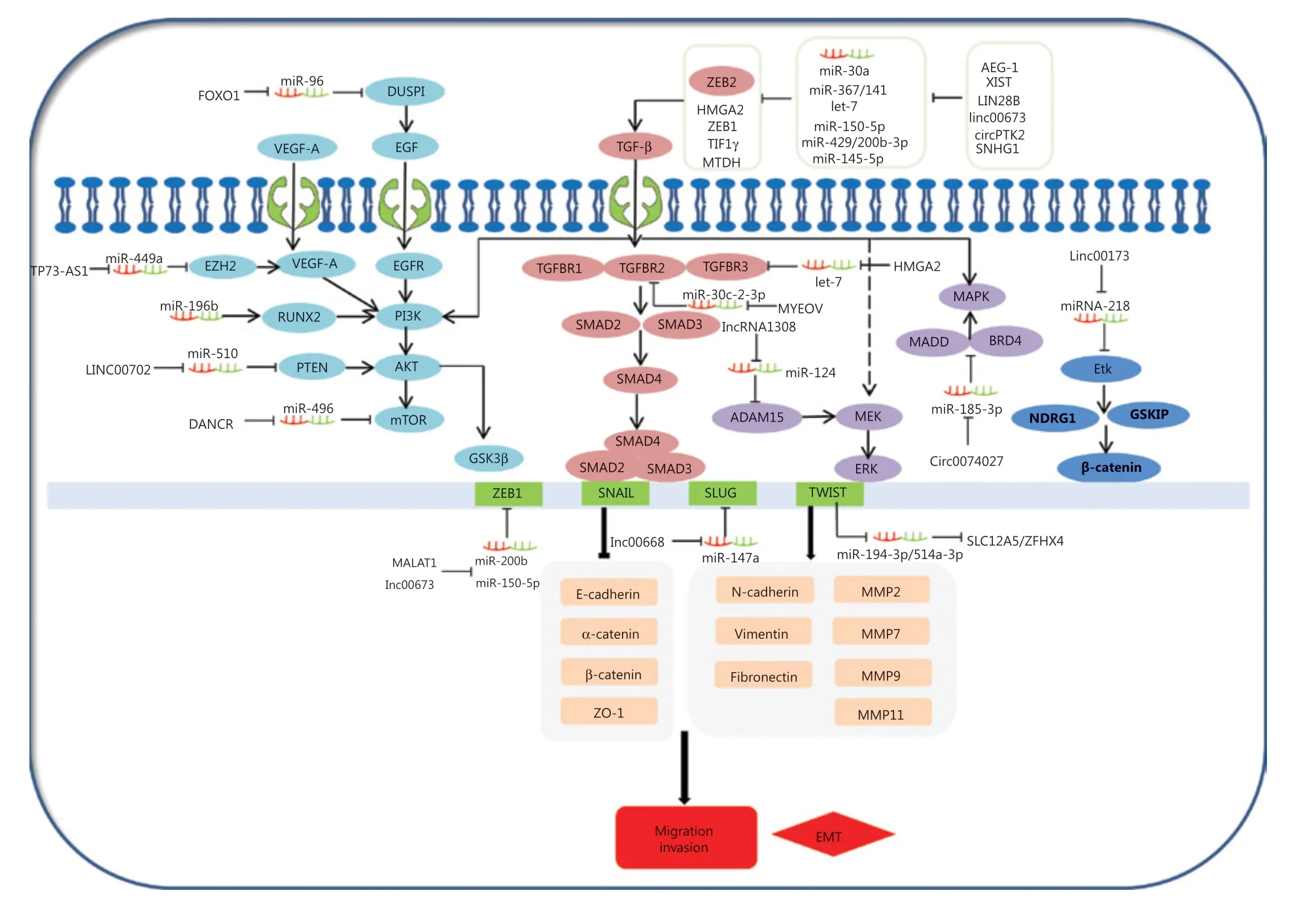

The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a common behavior of cells during cancer progression, and gives tumor cells migratory and invasive properties. The TGF-β pathway plays a central role in inducing the EMT in all types of tumors. TGF-βs can specifically bind to complexes of TGF-β receptor type 1 (TGFβR1), TGF-β receptor type 2 (TGFβR2), and TGF-β receptor type 3 (TGFβR3). This in turn leads to the phosphorylation of SMAD2 and SMAD3, which then form complexes with SMAD4. Moreover, the phosphorylated complexes of SMAD2, SMAD3, and SMAD4 lead to EMT activation related to molecules involved in several different mechanisms. Expressions of EMT-related transcription factors, SNAIL, SLUG, ZEB1, and TWIST, are activated by SMAD phosphorylated complexes. These collaborate to restrain EMT-related marker expressions of E-cadherin, α-catenin, β-catenin, and ZO-1, and in turn, stimulate the expressions of vimentin, N-cadherin, fibronectin, and MMPS. For example, TWIST1, as a ceRNA, can regulate SLC12A5/ZFHX4 levels by sponging miR-194-3p/miR-514a-3p to influence the EMT progression in lung cancer148. The linc00668-centered competing endogenous RNA mechanism then promotes invasion and migration of lung cancer by regulating slug expression levels69. Additionally, TGFBR2 and TGFBR3 expressions are regulated by the MYEOV and HMGA2 ceRNAs via a TGF-β signaling pathway, which plays a novel role in the invasion and metastasis of NSCLC14,56. Furthermore, AEG-1, XIST, LIN28B, linc00673, circPTK2, SNHG1, and cESRP1 function as sponges of miR-30a,, miR-367/141let-7, miR-150-5p, miR-429/miR-200b-3p, miR-145-5p, and miR-93-5p, and indirectly impact the TGF-β/Smad-induced EMT; subsequently, they regulate the molecular mechanism of the EMT-related transcription factors and markers (Figure 3)64,65,74,75,105,112,119. This suggests that ceRNAs activate EMT-associated regulators through the TGF-β/SMADs signaling pathway.

Figure 3 Competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) and the signaling pathways involved in lung cancer cell invasion and migration. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is important in the behavior of cells during cancer progression, which confers tumor cells with migratory and invasive properties. The TGF-β pathway plays a central role in inducing the EMT in all types of tumors. TGFβs specifically bind to complexes of TGF-βR1, TGF-βR2, and TGF-βR3, leading to the phosphorylation of SMAD2 and SMAD3, which then forms complexes with SMAD4. AEG-1, XIST, LIN28B, linc00673, circPTK2, SNHG1, and cESRP1 as ceRNAs affect the signaling/Smad-induced EMT. In addition to Smad-dependent pathways in TGF-β family signaling, the TGF-β also induces the non-Smad TGF-β signaling pathways, such as PI3K/Akt/GSK3β, MEK-ERK, and MAPK pathways. Smad-dependent pathways are involved in TGF-β family signaling. FOXO1, TP73-AS1, LINC00702, DANCR, and circ0074027 act as ceRNAs to participate in non-Smad TGF-β signaling pathways in the invasion and metastasis of lung cancer.

Diverse signaling pathways play predominant roles in the initiation and progression of the EMT to convert epithelial cells into mesenchymal cells, affecting gene levels and morphology. In addition to its signaling pathway through SMADs, TGF-β also induces PI3K/Akt/GSK3β, MEK-ERK, and MAPK signaling pathways (Figure 3), which also induce the EMT. PI3K-AKT is activated through TGF-β, which induces invasion and migration of lung cancer149,150. This shows that the PI3K-AKT-GSK3β pathway plays an essential role in the EMT process151. Overexpression of miR-196b inhibits the TGF-β induced EMT process, and also suppresses the PI3K-AKT-GSK3β pathway by inactivating Runx2 in lung cancer152. Additionally, epidermal growth factor (EGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) may induce the PI3K-AKT pathway, and subsequently increase the EMT-related regulator levels. For example, the TP73-AS1-miR-449a-EZH2 axis ceRNA network promotes tumor migration and metastasis via regulating VEGF-A/AKT signaling in lung cancer54,153. Finally, FOXO1, an important transcription factor, serves as a ceRNA to sponge miR-96. FOXO1 can also induce lung cancer migration and invasion progression by affecting the EGFR signaling pathway122.

TGF-β can also activate the MEK-ERK and MAPK pathways, leading to the EMT initiation and progression. For example, a novel lncRNA (lncRNA 1308) targets the miR-124/ADAM15, to regulate cell invasion through activation of the MEK-ERK pathway51,154. Circ_0074027 induces invasion of lung cancer via activating bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) and MAPK-activating death domain-containing protein expression levels110. Ultimately, loss of linc00173 expression downregulates Etk by functioning as a ceRNA to target miRNA-218, and induces the inactivation of GSKIP and NDRG1. This causes the nuclear translocation of β-catenin and promotes lung cancer migration and invasion26.

The ceRNAs as novel prognoses and diagnoses biomarkers

Tumor (or cancer) biomarkers are biological molecules in cancer patients that may be used to characterize known tumors. These biomarkers are produced by the tumor itself or by the body in response to the tumor, and can be used as an indicator of diagnosis, prognosis, and prediction. Most importantly, they can be used to provide information about the patient’s survival or response to therapy. The ultimate objective is to acquire available diagnostic and prognostic information from vast amounts of possible biomarkers by using the results from many studies. In summary, a diagnostic biomarker should provide information about clinical status, and potentially about specific treatment targets. A useful biomarker might also provide the location of the patient’s disorder and the severity of the illness. Similarly, an ideal prognosis biomarker may predict future clinical features, such as the speed of disease progression or the prediction of remission. There are some non-coding RNAs and coding-RNAs (validated as biomarkers) that function as ceRNAs and play an essential role in lung cancer progression. For example, linc81507 acts as a ceRNA for miR-199b-5p by reducing CAV1 expression levels. It indicates the tumor suppressive functions of linc81507 in NSCLC progression, and it can serve as a potential biomarker for diagnosis and prognosis in lung cancer78. In addition, NEAT1, a nuclear-enriched abundant transcript1, acts as a ceRNA for hsa-mir-98-5p by directly binding to and interfering with hsa-mir-98-5p-mediated regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase 6 (MAPK6). It has been suggested as a prognostic biomarker in lung cancer diagnosis83. Finally, a novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarker (LncRNA HOTTIP) used for clinical research of lung cancer has been proposed. LncRNA HOTTIP mediates the ceRNA network, which interferes with the expression of anti-apoptotic factor BCL-2, suggesting that HOTTIP may serve as a valuable biomarker in lung cancer patients90. However, diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers might have complex correlations with patient outcomes. Biomarkers that indicate a poor prognosis have motivated researchers to seek more effective and favorable therapeutic methods for treatment. The lncRNAs OIP5-AS1 and OGFRP1 that act as ceRNAs have also been found to be effective predictors of advanced clinical stage, lymph node metastasis, and poor prognoses for NSCLC patients, indicating their significant roles in cancer development and progression46,140. In summary, the development of diagnostic methods for NSCLC has been slow, and patient prognosis has historically still been regarded as poor. Hence, understanding the intricacies of biomarker interactions and the comprehensive mechanisms of biomarker molecules can increase treatment opportunities for cancer patients and provide more individualized care for patients with a poor prognosis.

Chemotherapy is one of the basic clinical treatments strategies for NSCLC. Cisplatin (DDP) and carboplatin-based chemotherapy drugs are widely used for lung cancer treatment155. However, resistance to chemotherapy results in a poor prognosis, and also limits the use of DDP in clinical applications. Chemoresistance has been a major challenge for chemotherapy in human lung cancers. Cisplatin sensitivity is associated with DNA repair, apoptosis, and autophagy, and ceRNAs play essential parts in lung cancer drug resistance156. For example, BAG-1 (Bcl-2 associated athanogene-1) is closely related to sensitivity to radio(chemo)therapy. Previous studies have verified that lncRNA XIST acts as a ceRNA to positively regulate the cisplatin resistance of LUAD through the let-7i/BAG-1 axis84. Moreover, Beclin-1, a biomarker of autophagy, can inhibit apoptosis and could improve drug resistance. PVT1 might function as a ceRNA for sponging miR-216b and regulating Beclin-1, to enhance cisplatin sensitivity through autophagy and anti-apoptosis85. DNA repair function is a crucial factor that can affect the efficacy of cisplatin resistance. Nucleotide excision repair (NER) is thought to closely determine drug resistance. A study reported that hsa_circ_0001946 might affect the cisplatin sensitivity of lung cancer cisplatin through NER. Checkpoint kinase 1 (CHEK1) is implicated in regulating and identifying DNA damage. It was reported that LINC00485 induced cisplatin resistance through acting as a ceRNA of miR-195 in NSCLC88. A combination of etoposide (VP-16)/irinotecan plus cisplatin is a chemotherapy regimen for SCLC. Research results have shown that Linc00173 may function as a ceRNA to affect SCLC chemoresistance improvement via regulating Etk expression26. These results also indicate that ceRNAs may serve as novel biomarkers for therapeutic targets and prognostic markers of lung cancer patients.

Conclusions and perspectives

However, there are several challenges regarding possible ceRNA therapy. First, the ceRNA regulatory network in lung cancer is multilayered and complicated, and the miRNAs are mainly involved with multiple non-coding RNAs. Therefore, nonspecific manipulation of mutational genes could impact and alter normal gene expressions. Second, an effective and specific delivery vector for ceRNA therapeutic agents must be developed. Ultimately, better therapeutics are needed to develop ceRNA-driven precision medicine, to provide new possibilities and directions for ceRNA use to overcome treatment obstacles, and aid in efforts to isolate and specifically target drugs capable of having anti-tumor activity.

Abbreviations

CeRNA: competing endogenous RNA; NSCLC: non-small cell lung cancer; SCLC: small cell lung cancer; LUAD: lung adenocarcinoma; LUSC: lung squamous carcinoma; MREs: MiRNA response elements; RBPs: RNA binding proteins; ncRNA: non-coding RNA; lncRNA: long noncoding RNA; HOTAIR: HOX transcript antisense RNA; PDPK1: 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1; TTN-AS1: Titin-antisense RNA1; CDK5: cyclin dependent kinase 5; EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition; CBS: cystathionine-β-synthase; LCAT1: lung cancer associated transcript 1; RAC1: Rac family small GTPase 1; TINCR: terminal differentiation-induced lncRNA; UCA1: urothelial carcinoma associated 1; PVT1: plasmacytoma variant translocation 1; MMP2: matrix metalloproteinase 2; XIAP: X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis; HOTTIP: HOXA transcript at the distal tip; EZH1: enhancer of zeste homolog 1; KLK4: Kallikrein-related peptidase 4; FAIM2: Fas apoptosis inhibitory molecule 2; ZEB1: Zinc-finger E-box binding homeobox 1; ZEB1-AS1: ZEB1 antisense RNA 1; NEAT-1: nuclear enriched abundant transcript 1; E2F3: E2F transcription factor 3; PRNCR1: prostate cancer non-coding RNA 1; HEY2: hairy and enhancer of split-related with YRPW motif protein 2; ADAM 15: a disintegrin and a metalloproteinase 15; PLSCR4: phospholipid scramblase; TP73-AS1: lncRNA antisense RNA of the TP73 gene; XIST: X-inactive specific transcript; PXN: Paxillin; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; TGFBR2: TGF-β receptor type II; MYEOV: myeloma overexpressed gene; USP15: ubiquitin specific protease 15; MALAT1: metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1; TFAP2C: transcription factor AP-2 gamma; HOXD-AS1: HOXD Cluster Antisense RNA; DANCR: differentiation antagonizing noncoding RNA; DGCR5: DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 5; EPHB6: EPH receptor B6; SNHG20: small nucleolar RNA host gene 20; DLX6-AS1: distal-less homeobox 6 antisense 1; PRR11: proline rich 11; SNHG6: small nucleolar RNA host gene 6; mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin; RRM2: ribonucleotide reductase M2 subunit; SNHG1: small nucleolar RNA host gene 1; MTDH: metadherin; IGF-2: insulin-like growth factor-2; CAV1: caveolin1; NORAD: non-coding RNA activated by DNA damage; MINCR: MYC induced long noncoding RNA; MINCR: MYC induced long noncoding RNA; CCND2: cyclin D2; Bcl-2: B-cell lymphoma-2; Bax: BCL2-associated X; MAPK6: mitogen-activated protein kinase 6; MRP1: multidrug resistance protein 1; CHEK1: checkpoint kinase 1; ZFAS1: ZNFX1 antisense RNA1; EGF: epidermal growth factor; EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor; DUSP1: dual-specificity phosphatase 1; FOXO1: forkhead box O1; RTKs: ectopic expression of receptor tyrosine kinases; PPDPF: Pancreatic progenitor cell differentiation and proliferation factor; MACC1: metastasis-associated in colon cancer 1; STAT3: signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; STK11: serine/threonine kinase 11; ENO1: enolase 1; cytC: cytochrome C; XIAP: Xlinked inhibitor of apoptosis protein; BRD4: bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) ; MADD: MAPK-activating death domain-containing protein; cESRP1: circular RNA epithelial splicing regulatory protein-1; TGFβR1: TGF-β receptor type I; PTEN: phosphatase and tensin homolog; MMPs: matrix metalloproteases; ERK: extracellular regulated kinase; MEK: mitogen-activated protein kinase/Erk kinase; E-cadherin: epithelial cadherin; GSK3β: glycogen synthase kinase-3β.

Grant support

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31670952 and 81902796).

Conflict of interest statement

No potential conflicts of interest are disclosed.

杂志排行

Cancer Biology & Medicine的其它文章

- The role and its mechanism of intermittent fasting in tumors: friend or foe?

- Association of systemic inflammation and body mass index with survival in patients with resectable gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinomas

- Exosome-mediated cellular crosstalk within the tumor microenvironment upon irradiation

- Predictive value of MGMT promoter methylation on the survival of TMZ treated IDH-mutant glioblastoma

- Patient-derived non-small cell lung cancer xenograft mirrors complex tumor heterogeneity

- BYSL contributes to tumor growth by cooperating with the mTORC2 complex in gliomas