Giorgio Vasari’s Fiery Putto: Artistic Armorial

2021-03-03LianaDeGirolamiCheney

Giorgio Vasari (1511-74) as an artist and art historian of Italian Mannerism viewed himself as huomo buono et docto in buon letter (a fine and learned man).1 In choosing to practice various arts such as writing treatises, collecting drawings, painting decorative cycles, designing buildings, and decorating facades, Vasari was viewed by humanists as a virtuoso. This Tuscan painter, architect, art collector, writer, and art historian is best known for his Vite de’ più eccellenti architetti, pittori e scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a’ tempi nostri (Lives of the Most Excellent Architects, Painters and Sculptors of Italy, from Cimabue to the present time), which was first published in 1550, followed by an enlarged edition illustrated with woodcuts of artists’ portraits in 1568.2 In 1960, Einar Rud(1892-1980), a Danish biographer and a scholar of Vasari, characterized him as the first art historian.3 By virtue of Rud’s text, Vasari is known as “the first art historian”—in particular, of Italian art—since Pliny the Elder wrote Book 35 on the History of Art in Ancient times in the Natural History, published posthumously in 79 CE.4 It is almost impossible to imagine the history of Italian art without Vasari, so fundamental is his Vite (Lives). This sixteenth-century Italian work is the first real and autonomous history of art because of its monumental encompassing of all of the following: (1) preambles for explanatory data on the function of the text; (2) integration of individual biographies (with anecdotal, gossipy, and amusing commentaries); (3) theory of art with articulations about artistic creativity and intentionality; and (4) inclusion of explanations of the function and types of artistic materials as well as their applications and techniques necessary for the productivity of art forms (that is, a formation of an instruction manual for artists and the manual’s application to material culture in the sixteenth century). In his coat of arms, Vasari visualized these creative activities and honored his Aretine artistic ancestry (Figure 1). This study consists of four parts: (1) a brief history of Vasari’s family; (2) a brief discussion of Vasari’s homes, Case Vasari; (3) a discussion on the location of his coat of arms (stemma) in the Case Vasari; and (4) and an interpretation of the meaning of Vasari’s coat of arms in his Aretine home.

Keywords: Giorgio Vasari, Case Vasari, coat of arms, Aretine heraldry, emblems, iconography, symbolism, studiolo (study), Renaissance visions and theories

1. Vasari’s Family

Giorgio Vasari was born on 30 July 1511 in Arezzo to Maddalena Tacci and Antonio di Giorgio Vasari. His birth and baptism are recorded in the Libro dei battesimi dell’Archivio della Fraternità: “c. 95: Battezati in Pieve[Church Santa Maria Annunziata della Pieve, Arezzo], Giorgio…di Antonio di Giorgio Vasaio…per mano di ser Piero di Pauolo, sagrestano” (Baptized in Pieve [Church of Santa Maria Annunziata of the Pieve, Arezzo] Giorgio … of Anthony of Giorgio, the potter … by the hands of Piero of Paulo, sacristan) (Figures 2 and 3).5

A few biographical notes about the family origin and Vasari’s initial education explain some of his cultural inclinations as well as the symbolism in his coat of arms. The earliest documentation about his family’s origins is confusing. Only a few records housed in the castle of the city of Cortona comment on the family’s name, their trade, and relocations. For example, Lazzaro di Niccolò de’ Taldi of Cortona was born in 1396 and died in 1468 at the age of 72.6 This was Vasari’s great-grandfather. Another record notes that in 1460, Lazzaro di Niccolò de’Taldi with his son Giorgio (Vasari’s grandfather, 1424-68 moved for economic reasons from Cortona to Arezzo in order to find a better market for their trade as sellaio e pittrore (saddler and painter), for Lazzaro, and as vasaio(pottery maker) for Giorgio. In the vita (biography) of Lazzaro Vasari (Vasari’s great-grandfather) (Figures 4a and 4b), Vasari stated that his grandfather died at the age of 68 in 1484. Vasari proudly boasted about the accomplishments of his ancestor as a designer and painter, assisting the renowned Aretine painter Piero della Francesca (1415-92), in the fresco paintings of the Legend of the True Cross in the main altar of the Basilica of San Francesco in Arezzo, commissioned by the Bacci family. His great-grandfather Lazzaro, and his father Antonio—and eventually Vasari himself—were buried in the family plot in the Church of Santa Maria Annunziata delle Pieve in Arezzo, the same church in which Vasari was baptized.)7

During the transfer from Cortona to Arezzo, at an unspecified date, Vasari’s ancestors, Lazzaro or Giorgio, changed the family surname from de’ Taldi to Vasari, in order to associate the family name with the present occupational trade of the family as potters or ceramicists, that is, vasaio. Later, for a more profitable income, Vasari’s grandfather, Giorgio, changed his occupation from potter to wool-maker (mercatura della pannina) and supplier of textiles (treccolo). He focused on the industrial aspect of the usage of wool material for making mattresses and other type of wool products, but retained his last name as “Vasaio” or Vasari.8 Finally, the Vasari family settled in Arezzo with a profitable labor trade. Giorgio Vasari—the artist—did not engage in his family trade. At an early age he opted to pursue the art of drawing and painting, following the artistic activities and interests of his long-distant relative Luca Signorelli (1441/45-1523)9 (Figures 5a and 5b). Although coming from an honorable family of manual laborers, Vasari trained himself to become an artist, aiming to elevate himself and those with the same vocation as professional artists and not just manual laborers.

2. Vasari’s Homes (Case Vasari)

Vasari resided in three homes: two in Arezzo and a third one in Florence. In the city of Arezzo, his native home of residence where he was born was in Canto de’ Perini, now known now as Via Mazzini 60 (Figure 6). A modern plaque marks this historic house, and still visible on the fa?ade of the house above the doorway is an insignia of a vessel, alluding to the family name vasaio and marking the family’s residence. Unfortunately, inside the house nothing remains of the original construction and furnishings. In order to continue the family legacy, Vasari conflated his honor and pride of the Aretine heritage with his artistic accomplishments in creating unique residential homes in Arezzo, his native home, the Casa Vasari in Via XX Settembre (1542-54/59) (Figure 7) and in Florence, the Casa Vasari in Borgo Santa Croce 8 (1560-62) (Figure 8).10

In the decorations of his private homes, Vasari reveals at one level, with their physical construction, decoration, and imagery, his artistic ability and technical mastery; and at another level—the metaphysical—his intellectual curiosity, enthusiasm and fascination for the antique and a delight for virtuosity, making it possible to present an original view of art in his private dwelling, creating a gallery of art in his palace and a personal museum.11 Years later, his artistic ability extended to other architectural interests as well, notably with the Galleria degli Uffizi in 1560 for the Duke of Florence.12

Moving into the intellectual circles of Florence and Rome, traveling throughout Italy, and becoming acquainted with the various arts in other centers of Italy, Vasari thought that artists could improve on, change, or assimilate different styles and could instruct their patrons about art. These experiences caused artists to not only admire the works of fellow artists but also collect them. The exchange of drawings assisted artists in valuing their art and in transmitting their artistic conceits to other artists and patrons.13 Moreover, their friendship and personal contact with patrons promoted them and advanced the recognition of their work.

In addition, as a consequence of his classical schooling, humanistic circles, patronage, and traveling contacts, Vasari became aware of the literary and printed traditions associated with emblematic and mythographic sources and their assimilation and application to artistic imagery. He recounted in his autobiography (vita) that his knowledge of emblems, hieroglyphs, and mythography derived from his formal education in the classics with the humanists Giovanni Pollastra (1465-1540) and Pierio Valeriano (1477-1558) in 1530; his contact with Andrea Alciato (1492-1550) in 1540, when he was painting the Refectory of San Michele in Bosco in Bologna; and his extensive interactions with the literati in the Roman circle of Pope Paul III (Farnese 1458-1549) in 1546, when he was decorating the Sala dei Cento Giorni in the Palazzo della Cancelleria in Rome.14 That circle included the art collector, philologist, and monk Vincenzo Borghini (1515-80); the lyric poet, satirist, and translator of classic Annibale Caro (1507-66); the historian and biographer Paolo Giovio (1483-52); the philologist M. Claudio Tolomei (1492-1556); and humanist and poet Francesco Maria Molza (1489-1544).

When Vasari purchased the Aretine house, he was enthusiastic because it had a garden to cultivate. As he wrote in his vita: “I bought a house already begun in Arezzo, with a site for making beautiful gardens, in the Borgo di San Vito, in the best area of the town” (Figures 7a and 7b).15 Vasari architecturally designed his house and conceived the iconographical program for the decoration in its interior. The piano nobile—the traditional living area of the owner—connects with the garden of the house (Figure 9). Among the chambers on this floor there is one on which I will focus here: a square room with a window called the Chamber of Fame, which functioned as a piccolo studiolo (small study) (Figures 8, 9, and 10). The thematic decorative layout in the Chamber of Fame consists of three levels. In the ceiling resides the personification of Fame, seated on a globe, blowing her trumpet to honor Vasari’s accomplishments. The second level is designed with the visual Fine Arts(Architecture, Painting, and Sculpture) and literary Arts (Poetry), alluding to Vasari’s intellectual abilities. Lunettes in the third level are decorated with ovati (ovals) containing portraits of Vasari’s ancestors and mentors(Lazzaro Vasari, Luca Signorelli, Andrea del Sarto, and Michelangelo) and himself, surrounded by decorative grotesques,16 a reference to Vasari’s artistic interests and training.

The structure of the ceiling consists of a tetto a vela (sail roof), and lunettes were decorated and painted in the traditional fresco technique. The walls were traditionally undecorated in order to hang tapestries, paintings, reliefs, or against which to place large furniture items: bookcases, chairs, sofas. A desk was probably set below the window for drawing, reading, and writing in order to receive direct light and share perfumed scents from flowers and fruits in the adjacent area, the garden of the house (compare Figures 11 and 7b).

A chair or desk near a window is seen in many Italian Renaissance paintings of humanists, heroic, and renowned religious figures reading, thinking, and working in their study, such as Vicenza Foppa, The Young Cicero Reading of 1464, now at the Wallace Collection in London (Figure 12); Giovanni Battista Moroni’s Bartolommeo Bonghi of 1553, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Figure 13); Giorgio Vasari’s Julius Caesar in the Act of Writing the Commentaries of 1560s, in Palazzo Vecchio; and paintings about religious scholars such as Saint Jerome in his Study and Saint Augustine in his Study, for example, and Vittorio Carpaccio’s Saint Augustine’s Vision of 1502, in the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, in Venice (Figure 14).

3. Vasari’s Coat of Arms in Case Vasari

Years after painting the Chamber of Fame, probably around 1548 when he was decorating another room in the house (the Chamber of Fortune) as a camera picta—a totally painted room, ceilings and walls—he also painted a winged putto with his coat of arms (stemma) in the lunette above the window in his study in the Chamber of Fame (Figures 15a and 15b). And for certain, Vasari completed the design of his putto decoration around 1548 and maybe touched it up before 1554-59, when he spent his last long sojourn in the Aretine house, finishing the decoration in the unpainted ceiling of the Chamber of the Apollo and the Muses.

In his Aretine house, in the Chamber of Fame, Vasari depicted for the first time his coat of arms (stemma) in the fresco technique but, ingeniously, repeated a similar motif of his coat of arms in oils in the corner of the ceiling of the Chamber of Fortune in 1548 (Figure 15a and 15b). Moreover, in his second designed home in Florence, Vasari expanded and elaborated on his coat of arms motif that is visible above the fireplace of the main reception room, the Sala of the Arts. This coat of arms combines Vasari’s own stemma and his wife’s family coat of arms—Niccolosa (Cosina) Bacci (Figures 16a and 16b). The Bacci family was an ancient and prominent Aretine family. They were among the benefactors of the Basilica of San Francesco in Arezzo, where their coat of arms is displayed prominently in pillars of the main altar (Figures 17a and 17b). Vasari’s great-grandfather, Lazzaro, had collaborated with the teacher Piero della Francesca in the design of this church, perhaps even painting the Bacci’s stemma.

4. Vasari’s Aretine Coat of Arms, an Interpretation

In the studiolo of his Aretine chamber, the composition of Vasari’s coat of arms is of two parts: a winged putto and a cartouche (Figures 1, 11 and 18). The blond, nude putto is wearing a sash around his waistline, terminating in a knotted ribbon. Vasari depicted this putto as a natural and celestial being. The blue-colored wings allude to his angelic nature—goodness and beauty—while his nude figure, portrayed as a healthy bimbo, refers to his human nature. The putto kneels down to hold and steady a heavy and large gilded cartouche. This cartouche, decorated with a large flowing ribbon of red color, contains emblematic devices. The putto gazes down and below at the desk (scrittorio) where Vasari’s paraphernalia can be seen, or at Vasari himself seated at his desk drawing, reading, writing, or actively engaged in his intellectual pursuits.

Vasari’s cartouche is composed of four parts: (1) a simulated metal scroll rolls up at the end; (2) an oval(ovato) escutcheon (shield or plaque) containing the family heraldic icons appears in the center; (3) an oval medallion with a relief mask is placed on the side of the escutcheon; and (4) a flowing, large sash encircles the top of the stemma and extends into the space of the lunette.

In his book on Le Antiche Famiglie di Arezzo e del Contado, Giovanni Nocentini discussed the origins of Vasari’s family and also illustrated the family’s coat of arms. It consists of a stemma whose center shows three rampant and winged griffins supported by alternating stars and striped banners.17 It is unclear when this heraldic crest was designed; probably in the Quattrocento, when the family moved to Arezzo.

When comparing the Vasari family’s stemma with Vasari’s own stemma, the following is observed(compare Figures 19 and 20). Vasari’s stemma shows the field or pale of the escutcheon composed of two parts: at top in a blue-colored background are the heads of two griffins facing each other, one of red color and the other of gold color. These griffins are not winged. The bottom part of the design contains patterns with alternating stripes of gold and red colors. These colors are associated with the area of Cortona and Arezzo,18 heraldic colors from the regions of Vasari’s ancestry.

In classical and Christian iconography, the griffin is considered a mythical animal that symbolizes enlightenment, wisdom, and protection.19 The depiction of three griffons or griffins in the Vasari family’s stemma is unclear. Traditionally, only two griffins are depicted in coats of arms, alluding to the dual role of the creature: its protective nature and intellectual power. Perhaps the Vasari family’s stemma with the trio of griffins alludes to the three founding members of the family (Lazzaro, Giorgio, and Antonio) or, metaphorically, alludes to their professions as painter of saddles, potter, and wool-maker.

In his own coat of arms, Vasari reduced the number of griffins from three to two, adhering to the traditional mythical understanding of the creature as imparter of knowledge and cosmic guardian of secrets and treasures as represented in an ancient Roman imperial sculpture, e.g., Emperor Trajan (53-177 CE), marble statue, dated 110 CE, now in the New Danish Museum (Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek) in Copenhagen, Denmark. In front of Trajan’s body armor (cuirass) are incised two large winged griffins facing each other, demonstrating their fearless and heroic powers (Figure 21). But most pertinent to his coat of arms, Vasari’s imagery reveals his familiarity with his tutor Valeriano’s studies on hieroglyphs and mythography and the intellectual discourses he experienced in the Roman cultural circle during the reign of Pope Paul III (Farnese Pope 1534-49).20

In Hieroglyphica, Valeriano commented on the Bembine Table of Isis, Book 20, narrating the history of Egypt with “countless griffins and other fabulous animals which with their mystical philosophy were disseminated from Egypt all over Greece and Italy (Figure 22).21 Valeriano also noted that the table was made in gold and silver. But when the Egyptian table was copied in Rome during the first century CE, the table was made of bronze, with enamel and silver inlay. The saga surrounding the history of this Roman copy continued during the Italian Renaissance. After the Sack of Rome in 1527, the Venetian poet and literary theorist Cardinal Pietro Bembo (1470-1547), an avid collector of antiques, purchased the Egyptian table known as Table of Isis (Mensa Isiaca or Isiac Table) from an ironworker in Rome. During the Italian Renaissance, this Egyptian table became known as and named the Bembine Tablet after Bembo’s last name (Figure 22).22 Pietro Bembo was appointed as Latin Secretary to Pope Leo X (Medici Pope 1513-21) in Rome after writing a book on Prose della volgar lingua(Prose of the Vernacular Tongue) in 1512, using as an example and praising the Tuscan dialect as a vernacular language recalling Dante’s language, Francesco Petrarch’s poetry, and Giovanni Boccaccio’s prose. Years later, in 1538, Pope Paul III conferred upon Bembo the cardinalate, hence Cardinal Pietro Bembo.

Most of the visual conceits integrated and displayed for his coat of arms related to Vasari’s observations about honorific plaques displayed in Florentine palaces—the Palazzo Davanzati23—courtyards of municipal and military buildings—Bargello24—and frontages of public buildings in his home town of Arezzo. In the Palazzo Pretorio (Palace of Justice) in Arezzo, for example, medieval and Renaissance heraldic coats of arms of illustrious historical figures, captains, charitable societies, and military institutions had been displayed in the fa?ade since the fourteenth century; this was a well-known edifice among Aretine citizens like Vasari (Figure 23). Vasari also, as an Aretine, wanted to display his stemma to honor himself in his home where he had created a private museum.25

Vasari’s design of a scroll motif rolling at the top and end of the cartouche imitates the design of a written parchment, which symbolically alludes to a written proclamation as well as to a written honorific document or a written discourse. In all of these instances, there are allusion to Vasari’s successful writing of the first edition of the biographies of the artists (Vite) in 1550 (Figure 24). The design of the scroll also refers to commendations for his many decorative cycles in Venice, Naples, Rome, and Florence.

In Vasari’s stemma, the placement of the relief head or an enigmatic face in an ovato format is most ingenious(compare Figure 1, 11, 18, and 20). The enigmatic face in the stemma is only depicted in the lunette of the Chamber of Fame in the Aretine house. The design of an oval shape with a portrait face is similar to the depiction of Vasari’s ancestors and teachers depicted in the ovati decorations inside the lunette walls of the Chamber of Fame in Vasari’s studiolo. Traditionally, in Italian Renaissance art, the conceit of an image of a head in relief and inside an oval format is a symbol of honor and recognition, as noted in ancient and Renaissance portraits of heroic and famous figures in coins, medals, or cameos. Examples include Giovanni Antonio de’ Rossi’s Cameo of Lorenzo de Medici of 1490, Museo. degli Argenti in Florence;26 and the bronze medal of Niccolò di Forzore Spinelli’s Lorenzo de’ Medici (1448-92), now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.27

The imaging of a figure holding a medal or carrying a medal as in Vasari’s putto holding the stemma derives from the Italian visual tradition found in Renaissance portrait paintings, where men hold a medal or a medallion of a distinguished or loved persona, for example, Botticelli’s Portrait of a Man with the Medal of Cosimo de’Medici The Elder of 1475, now at the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence;28 Agnolo Bronzino’s Portrait of Ludovico Capponi of 1550, now at the Frick Collection in New York City;29 and Sofonisba Anguissola’s Portrait of Giulio Clovio of 1556, now in the Collection of Eugenio Malgeri Zeri in Rome.30

In composing his coat of arms, Vasari was also appropriating the emblematic tradition of composing imprese or emblems using a cartouche motif containing a visual conceit as represented in Andrea Alciato’s emblem books, Emblemata, in particular, in the emblems entitled Insignia of the Duke of Milan, Chastity, Prudence, and Insignia of the Poets. In these mentioned examples, the emblematist, Alciato, composed a Latin inscription or motto alerting the reader about the message to be inferred in the emblem. The pictura shows a type of seascape or landscape in the background of the scene, which functions as a vignette or setting for the signification of the image in the foreground. Of note is the landscape in Insignia of the Poets, which shows the plain and watery area of the River Po, recalling Alciato’s homeland. In the foreground of these mentioned emblems, there is a cartouche in the pictura, which is nailed or tied up to a tree truck or hangs from a pole, suggesting strength and stability of action or thought. Inside this cartouche, the depicted anima in the pictura is a metaphor for an abstract human behavior—prudence, purity of heart, and guardian of virtues. In turn, the allegorical allusions are associated with specific aspects of a persona, revealing the virtues of an individual in terms of character, abilities, and achievements.

In the emblem Prudens Magis Qua (Wise head, close mouth), for example, the motto alludes to the signification that a prudent person should refrain from loquacity (Figure 26). Here the pictura (image) shows an owl placed in the center of the cartouche. The subscriptio or text in the emblem comments that the owl is a symbol of Prudence because of having wisdom or being prudent without demonstrating eloquence or imposing persuasiveness, that is, a “wise head and a close mouth.” The meaning of the emblem is associated with the mythological deity Minerva, Goddess of Wisdom, who preferred the owl for its eloquence and prudent behavior above the other birds, as noted in Ovid, Metamorphoses 2.562-565. Another of Alciato’s emblems, with the motto Insignia Po?tarum (Insignia of Poets), illustrates in the pictura in the center of a cartouche the image of a swan (Figure 27). The subscriptio comments that the swan is a symbol of music and poetry, associating this animal with Apollo, the God of Music and Poetry, also noted in Ovid’s Metamorphoses 2.367ff.31 In these emblematic examples, the motto (title), pictura, and subscriptio are all associated with a specific persona or patron who commissioned the design or emblem. Thus, the overall composition of Alciato’s emblems alludes to a moral reference or provides a teaching message to the viewer, employing the moral attributes of a persona or illustrating the good virtues of a patron. Vasari appropriated the allusions of moral values and significations in the conceit of his coat of arms.

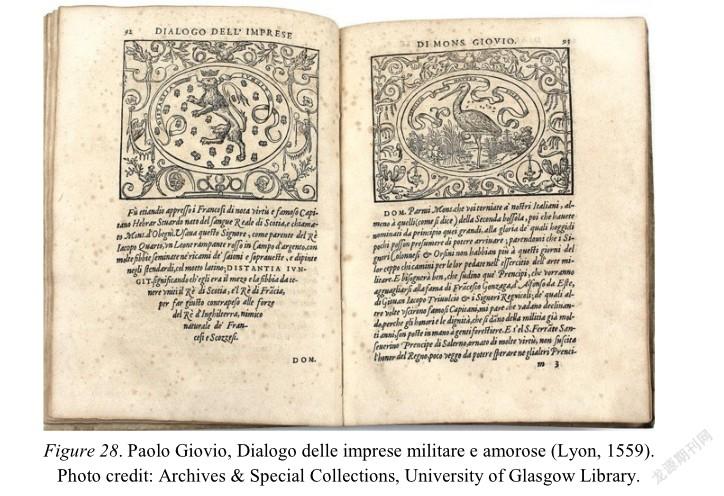

In Bologna, having interacted with Alciato and aware of his collection of emblems, Vasari appropriated some these emblematic conceits in formatting the cartouche design in his coat of arms to honor himself as a prudent (wise) individual, a moral person, and painter-poet persona. For the design of the floating sash or ribbon, Vasari also followed the motif found in Alciato’s emblems and in Paolo Giovio’s imprese. Giovio’s method consisted of embellishing the pictura with floating ribbons that sometimes contained Latin inscriptions; at other times he used an ornament as seen in the imprese on Clovis (39), Suave (34), and Semper (36) represented in the Dialogo delle imprese militare e amorose (Figure 28).32 Vasari artistically employed the sash around the cartouche to unite the winged putto and the cartouche, paralleling the flowing moment of the sash with the ribbon around the putto’s waist.

In his paintings as well as in his coat of arms, Vasari interplayed with conceits of the real and the artificial; the visible and the imaginary; and the revealed and the concealed. With the depiction of the putto and the enigmatic face, for example, Vasari showed two ways of perceiving: physical and metaphysical (Figure 1). There is a natural, physical aspect of seeing, as with the putto’s eyes, which are looking down in the room, focusing at a particular object. And there is a metaphysical aspect of internal seeing, noted in the enigmatic face (oval mask type on the side of the cartouche), whose eyes are looking out, not focusing onto a particular object but absorbing and assessing the perception of the whole area. Hence the eyes of the enigmatic face indicate the capturing of a mental imagery, that is, a meditative state of intellectual seeing or pondering on artistic and intellectual matters.

Vasari is commenting on the pre-eminence of the eye for acquiring human knowledge in artistic and intellectual matters, similar to the studies and treatises by Leonardo da Vinci (1542-19) on optics, seeing, and vision as portrayed in a pen-and-ink drawing of an eye at the Royal Collection Trust in London (RCIN 912436)(Figure 29) as well as aesthetic proportions and perceiving by Leon Battista Alberti (1404-72).33 Alberti visually rendered the concept of seeing in his Self-Portrait of 1435, a bronze medal made by Matteo de’ Pasti, now at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.34 The design of an all-seeing winged eye is Alberti’s personal emblem, using the Latin inscription, “Quid Tum” (What Then! or What Next?) (Figure 30). This phrase was employed by Cicero (106-43 BCE) during his orations in order to achieve attention from his audience, making a dramatic pause after his phrase.35 With enthusiasm, Alberti described the signification of his emblem of the winged eye, which has significant interrelations between physical and metaphysical ways of seeing, which Vasari appropriated in the conceit of his stemma. Alberti wrote:

La corona, nel primo, è simbolo di gloria e gioia. Non c’è niente di più potente, attento o degno dell’occhio. In breve,è la più importante delle parti del corpo, una sorta di re o dio. Gli antichi non consideravano forse Dio come una specie di occhio dato che controlla tutto e giudica ogni cosa singolarmente? Da un lato siamo contenti di rendere gloria a Dio per tutto, di gioire e avvicinarci a Lui con la mente e con la virtù e di considerarlo come un testimone onnipresente nei nostri pensieri e azioni. Dall’altro lato ci viene comandato di essere vigili e cauti per quanto possiamo, cercando ogni cosa che ci possa guidare alla gloria della virtù e di rallegrarci ogni volta che, col nostra lavoro e operosità, raggiungiamo qualcosa di nobile o divino.

(First of all, the cornea is a symbol of glory and joy. There is nothing more powerful, attentive (worthy) of the eye. In short, it is the most important of the parts of the body, a kind of king or god. Did not the ancients perhaps consider God as a kind [special] of eye given to control and judge everything individually? On the one hand, we are content to give glory to God for everything, to rejoice and approach Him with the mind and virtue to consider Him as an omnipresent witness of our thoughts and actions. On the other hand, it is commanded to us to be vigilant and cautious as much as we can, seeking everything that can guide us to the glory of virtue and to be joyful every time that with our work and industry we regain something noble or divine).36

In connecting Vasari’s type of visions found in his coat of arms, I am also adopting Markus Rath’s Albertian vision theory. Rath composed two drawings of Alberti’s flying eye relating to two types of perceiving: a directional vision versus a peripheral vision, which are also implied respectively in Vasari’s putto (directional vision) and enigmatic face (peripheral vision) (Figure 31).37 The directional visual implies the ability to focus in space and time on a determined moving visual object, as Vasari’s putto looks down metaphorically to Vasari’s desk or at Vasari drawing, reading, or writing at this desk. The peripheral vision ascribed to the enigmatic face alludes to the ability of the eyes to focus not only on a specific object but also outside the visual field, hence encompassing a great visual area and meaning, that is, pondering or understanding the significations of metaphysical seeing or intellectual seeing.

Continuing with the decoding of the meaning of the enigmatic face, another possible reference for this imagery is its visual association with the face of a sphinx, connecting it as well with the griffin’s symbolism in the cartouche. Both the sphinx and the griffin are traditional symbols of guardians of secret knowledge. With this in mind, Vasari remembered the original composition of Andrea Castagno’s Last Supper of 1445, in the refectory of Convent of Santa Apollonia,38 where sphinxes frame the seated area of the Florentine cenacolo, guarding and revealing the miraculous event of the creation of the Eucharist to the viewer (Figure 32). Thus, in Vasari’s stemma, the sphinx (enigmatic face) guards his mind and its significations as well as his house.

In sum, when looking at Vasari’s coat of arms, one ponders on Vasari’s artistic ability, literary background, fascination with collecting art objects (especially drawings), and the historical consciousness that contributed to the formation of his interest in writing biographies about other Tuscan artists as well as his own. His quest to establish the role of the artist as an inventor and not as a laborer prompted him to also appropriate, for his coat of arms, the honorific validation of noblemen, merchants, and humanists employed in their composing and displaying devices, insignia, emblems, and coats of arms. His interest in establishing artistic affinities, ancestral lineage, and family hegemony encouraged Vasari to write biographies about artists, to collect drawings, and to make his residences visual museums. With his Aretine pride and tradition, Vasari provided moral and economic support for his family, obtaining dowries and proper marriages and living accommodations for his sisters. With civic pride, he paid tribute to his native city with architectural embellishment and renovation of altars and churches. And as a native son, he honored his city with his personal artistic and literary accomplishments. It is within this cultural and intellectual frame that Vasari designed his coat of arms.

References

Alciato, A. (1549). Los emblemas. Lyons: Macé Bonhomme for Guillaume Rouille.

Alciato, A. (1551). Emblemata. Lyons: Macé Bonhomme for Guillaume Rouille.

Baroni Vannucci, A. (2021). Giorgio Vasari e Giovanni Stradano per la Fraternita dei Laici di Arezzo. Atti del Convegno su Omaggio a Cosimo I e Arezzo. Florence: Giunti, forthcoming.

Bates, W. (1868). The Brazen table of Bembo & Hieroglyphs. Retrieved from http://penelope.uchicago.edu/oddnotes/bembo.html(accessed 15 October 2021), also referencing Notes & Queries (4th s. ii 40) (October 3, 1868), p. 328.

Bettarini, R., & Barocchi, P. (Eds.) (1966-1976). Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori, nella redazioni del 1550 e 1568. (6 Vols). Florence: S.P.E.S.

Brendel, H. (2021). Image acts: A systematic approach to visual agency. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Carman, C. H. (2014). Leon Battista Alberti and Nicholas Cusanus: Toward an epistemology of vision for Italian renaissance art and culture. Farnham: Ashgate.

Cecchi, A. (1998). Le case del Vasari ad Arezzo e Firenze. In R. P. Ciardi (Ed.), Case di artisti in Toscana (pp. 29-74). Cinisello Balsamo [Milan]: Pizzi.

Cheney, L. De G. (2006). The homes of Giorgio Vasari. London: Peter Lang Publishers.

Cheney, L. De G. (2007). Giorgio Vasari’s teachers: Sacred and profane art. London: Peter Lang Publishers.

Cheney, L. De G. (2011). Einar Rud’s Vasari’s life and lives: The first art historian. Washington, DC: New Academia.

Cheney, L. De G. (2014). Giorgio Vasari, artist, designer, and collector. In D. J. Cast (Ed.), Ashgate Research Companion of Giorgio Vasari (pp. 41-77). Farnham: Ashgate.

Chevalier, J., & Gheerbrant, A. (1994). Dictionary of symbols (J. Buchanan- Brown, Trans.). London: Blackwell.

Collobi-Ragghianti, L. (1973). Vasari Libro dei Disegni (2 Vols). Milan: Architettura.

Conforti, C. (Ed.) (2011). Vasari, gli Uffizi e il Duca. Florence: Giunti.

Egan, J. A. (2014). Leon Battista Alberti (Cryptically) expresses: “The Eye Is a Camera Obscura.” Newport: RI: Cosmopolite Press.

Fiorani, F., & Nova, A. (2021). Leonardo da Vinci and Optics. Venice: Marsilio.

Giehlow, K. (2015). The humanist interpretation of hieroglyphs in the allegorical studies of the renaissance (R. Raybould, Trans. and Ed.). Leiden: Brill.

Giovio, P. (L. Domenichi, G. Simeoni). (1559/1574). Dialogo delle’imprese militare e amorose. Lyons: Guillaume Rouille.

Grafton, A. (2002). Leon Battista Alberti: Master builder of the Italian renaissance. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kemp, M. (1977). Leonardo and the visual Pyramid. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 140, 128-194.

McHam, S. B. (2013). Pliny and the artistic culture of the Italian renaissance. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Metford, J. C. J. (1983). Dictionary of Christian lore and legend. London: Thames and Hudson.

Nocentini, G. (1995/2000). Le Antiche Famiglie d’Arezzo e del contado. Arezzo: Edizioni Helicon.

Pierguidi, S. (2001). Vasari, Borghini, and the Merits of drawing from life. Master Drawings, 49(2), 171-174.

Proietti, T. (2010). Concinnitas: Principi di estetica nell’opera di Leon Battista Alberti. Rome: Nuova Cultura, Hortusbooks.

Rath, M. (2009). Albertis Tastauge: Neue Betrachtung eines Emblems visueller Theori. Bild Wissen Technik, Kunsttexte.de, 1, 1-7.

Rubin, P. L. (1995). Giorgio Vasari: Art and history. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Satkowski, L. (1993). Giorgio Vasari: Architect and courtier. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Scher, S. (1994). The currency of fame: Portraits medals of the renaissance. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

Sear, D. (2000-2011). Roman coins and their values (4 Vols). London: Spink Books.

Vasari, G. (1912/1979). Lives of the most eminent painters, sculptors and architects (3 Vols) (G. Du C. de Vere, Trans.). New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

Vasari, G. (1970-1974). Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori et architettori (9 Vols). G. Milanesi (Ed.). Florence: G. C. Sansoni.

Volkman, L. (2018). Hieroglyph, emblem, and renaissance pictography (R. Raybould, Trans. and Ed.). Leiden: Brill.

Watkins, R. (1960). L. B. Alberti’s Emblem, The Winged Eye and His Name, Leo. Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz, 9(3-4), 256-258.

Wellington Gahtan, M. (Ed.). (2016). Giorgio Vasari and the birth of the museum. London: Routledge.

Wind, E. (1971). Misteri pagani del Rinascimento. Milan: Adelphi.

Wittkower, R., & Wittkower, M. (1969). Born under saturn. New York: Norton.

1 I am borrowing Vasari’s description of Raphael’s role, which applies also to Vasari. Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori, ed. Gaetano Milanesi, 9 Vols. (Florence: G. C. Sansoni, 1970-74) 4:384-85; Rudolph Wittkower and Margot Wittkower, Born Under Saturn (New York: Norton, 1969), 16.

2 See the editions of Rosanna Bettarini and Paola Barocchi, eds., Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori, nella redazioni del 1550 e 1568, 6 vols. (Florence: S.P.E.S, 1966-76); and Gaetano Milanesi, Le vite. For an English translation of Vasari’s Vite, based on Vasari’s 1568 edition, see: Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, trans. Gaston Du C. de Vere, 3 vols. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1979), hereafter cited as De Vere-Vasari. De Vere’s translation first appeared in 1912; was subsequently reissued by Harry Abrams Publishers, New York, in 1979, with an Introduction by Lord Kenneth Clark; and was reissued by Modern Library Publishers, New York, in 2006, with an Introduction by Philip Jacks.

3 Einar Rud, Vasari’s Life and Lives: The First Art Historian, Introduction. In 1963, the Danish edition was translated into English and published by Thames & Hudson in London. See Liana De Girolami Cheney, Einar Rud’s Vasari’s Life and Lives: The First Art Historian (Washington, DC: New Academia, 2011); Liana De Girolami Cheney, The Paintings of the Casa Vasari(New York: Garland Publishing Company, 1985), revised and expanded as The Homes of Giorgio Vasari (London: Peter Lang Publishers, 2006 in English), and Trans. in Italian as Le Dimore di Giorgio Vasari (London: Peter Lang Publishers, 2011). See also Patricia Lee Rubin, Giorgio Vasari: Art and History (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1995), Introduction; and Liana De Girolami Cheney, Giorgio Vasari’s Teachers: Sacred and Profane Art (London: Peter Lang Publishers, 2007), Introduction.

4 Sarah Blake McHam, Pliny and the Artistic Culture of the Italian Renaissance (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013).

5 Alessandra Baroni Vannucci, “Giorgio Vasari e Giovanni Stradano per la Fraternita dei Laici di Arezzo,” in Atti del Convegno su Omaggio a Cosimo I e Arezzo (Florence: Giunti, 2021), forthcoming; Giovanni Nocentini, Le Antiche Famiglie d’Arezzo e del contado (Poppi: Edizione M.E.M., 1995, repr. Arezzo: Helicon, 2000), 71, citing the archival documents from the church(“Vacchetta dei battezzati in Pieve”) and the Fraternita dei Laici of Arezzo.

6 Nocentini, Le Antiche Famiglie d’Arezzo e del contado, 70. When comparing the dates with Vasari’s vita of his ancestor, Lazzaro Vasari, 1399-1452, there is a discrepancy in the years.

7 In De Vere-Vasari, the Vita of Lazzaro Vasari, 1:459-504, states that Vasari’s grandfather died at the age of 68 in 1484 and, along with his father Lazzaro, was buried in the family plot in the Church of Santa Maria Annunziata delle Pieve.

8 See Nocentini, Le Antiche Famiglie d’Arezzo e del contado, 71.

9 De Vere-Vasari, Vita of Luca Signorelli, 1:764-78.

10 Cheney, The Homes of Giorgio Vasari, 87-187; Alessandro Cecchi, “Le case del Vasari ad Arezzo e Firenze,” in Case di artisti in Toscana, ed. Roberto Paolo Ciardi (Cinisello Balsamo [Milan]: Pizzi, 1998), 29-74.

11 See Cheney, The Homes of Giorgio Vasari, Preface, xiv, and 186-90, noting that Vasari’s constructed his house as a palace and museum; Liana De Girolami Cheney, “Giorgio Vasari, Artist, Designer, and Collector,” in Ashgate Research Companion of Giorgio Vasari, ed. David J. Cast (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014), 41-77, esp. 41; and, recently, Maia Wellington Gahtan, ed., Giorgio Vasari and the Birth of the Museum (London: Routledge, 2016).

12 Leon Satkowski, Giorgio Vasari: Architect and Courtier (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993); Claudia Conforti, ed., Vasari, gli Uffizi e il Duca (Florence: Giunti, 2011).

13 See Licia Collobi-Ragghianti, Vasari Libro dei Disegni, 2 vols. (Milan: Architettura, 1973); and Stefano Pierguidi, “Vasari, Borghini, and the Merits of Drawing from Life,” Master Drawings 49, 2 (2011): 171-74.

14 De Vere-Vasari, Vita of Giorgio Vasari, 3:2241-44.

15 De Vere-Vasari, Vita of Giorgio Vasari, 3:2234.

16 The grotesques were heavily retouched and/or designed by Raimondo Zaballi (Zabagli d. 1842/45 in Arezzo) in 1827, when he painted the ceiling of the kitchen and retouched some of the ceilings and walls in the house. See Cheney, The Homes of Giorgio Vasari, 25.

17 Nocentini, Le Antiche Famiglie di Arezzo e del Contado, 270-76.

18 See https://www.herebdragons.com/chimera-bearded-dragon (accessed 15 August 2021), for the Cortona-Arezzo heraldry.

19 Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrant, Dictionary of Symbols, trans. John Buchanan-Brown (London: Blackwell, 1994), 458; J. C. J. Metford, Dictionary of Christian Lore and Legend (London: Thames and Hudson, 1983), 115.

20 Karl Giehlow, The Humanist Interpretation of Hieroglyphs in the Allegorical Studies of the Renaissance, trans. and ed. Roby Raybould (Leiden: Brill, 2015), chap. 5, on Hieroglyph Studies in the Italian Cinquecento, 150-207; and chap. 6, on The Hieroglyphica of Pierio Valeriano Bolzano, 208-35.

21 Ludwig Volkman, Hieroglyph, Emblem, and Renaissance Pictography, trans. and ed. Robin Raybould (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 71.

22 Volkman, Hieroglyph, Emblem, and Renaissance Pictography, 251. After Bembo’s death, the Table became part of the Gonzaga Collection in Mantua. Today it is located in the Museo Egizio in Turin. See William Bates, “The Brazen Table of Bembo & Hieroglyphs,” online at http://penelope.uchicago.edu/oddnotes/bembo.html (accessed 15 October 2021), also referencing Notes & Queries (4th s. ii 40) (October 3, 1868): 328.

23 For the image, see: https://florence-on-line.com/palazzos/museum-of-palazzo-davanzati.html (accessed 15 October 2021). 24 For the image, see: https://www.theflorentine.net/2019/03/05/bargello-museum-florence/

(accessed 15 October 2021).

25 Cheney, The Homes of Giorgio Vasari, Preface, xiv, noting that Vasari constructed his house as a palace and museum.

26 See David Sear, Roman Coins and Their Values, 4 vols. (London: Spink Books, 2000-11), for a discussion on Caesar Augustus(63 BCE-14 CE), also known as Octavian, who was the first and among the most important of the Roman emperors to employ the symbol of the griffin. For the image, see: https://www.akg-images.co.uk/archive/-2UMEBMYL2YJW9.html (accessed 15 August 2021).

27 See Stephen Scher, The Currency of Fame: Portrait Medals of the Renaissance (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994); for the image, see: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/200634 (accessed 15 August 2021).

28 For the image, see:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portrait_of_a_Man_with_a_Medal_of_Cosimo_the_Elder#/media/File:Sandro_Botticelli_-_Portrait_ of_a_Man_with_a_Medal_of_Cosimo_the_Elder.jpg (accessed 15 August 2021).

29 For the image, see: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Angelo_Bronzino_055.jpg (accessed 15 August 2021).

30 For the image, see:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sofonisba_Anguissola-_Retrato_de_Giulio-Clovio-óleo-sobre-lienzo-1556-Roma-colec ción-particular.jpg (accessed 15 August 2021).

31 See Andrea Alciato, Los emblemas (Lyons: Macé Bonhomme for Guillaume Rouille, 1549); and Andrea Alciato, Emblemata(Lyons: Macé Bonhomme for Guillaume Rouille, 1551).

32 See Paolo Giovio (L. Domenichi, G. Simeoni), Dialogo delle’imprese militare e amorose (Lyons: Guillaume Rouille, 1559/1574). For the images, see: https://www.italianemblems.arts.gla.ac.uk/contents.php?bookid=sm_0520 (accessed 15 August 2021).

33 The scholarly research on these two artists is extensive. For Leonardo da Vinci, I will just mention Martin Kemp, “Leonardo and the Visual Pyramid,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 140 (1977): 128-94; and Francesca Fiorani and Alessandro Nova, Leonardo da Vinci and Optics (Venice: Marsilio, 2021). For Leon Battista Alberti, see Anthony Grafton, Leon Battista Alberti: Master Builder of the Italian Renaissance (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002) and references mentioned in subsequent notes.

34 For the image, see: https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.43845.html (accessed 15 August 2021).

35 Motto from Cicero’s Tusculanae disputationes, II.11.26. See Edgar Wind, Misteri pagani del Rinascimento (Milan: Adelphi, 1971), 283, for an ancient reference to l’occhio alato (winged eye) in Virgil (Aeneid, IV.543; Eclogues, X.38).

36 For a complex discussion on the symbolism of Alberti’s Self-Portrait and the image of the eye, see Renée Watkins, “L. B. Alberti’s Emblem, The Winged Eye and His Name, Leo,” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 9, 3-4(November 1960): 256-58 (my translation of the passage); Tiziana Proietti, Concinnitas: Principi di estetica nell’opera di Leon Battista Alberti (Rome: Nuova Cultura, Hortusbooks, 2010), 104; and James Alan Egan, Leon Battista Alberti (Cryptically) Expresses: “The Eye Is a Camera Obscura” (Newport: RI: Cosmopolite Press, 2014).

37 Markus Rath, “Albertis Tastauge: Neue Betrachtung eines Emblems visueller Theorie,” Bild Wissen Technik, Kunsttexte.de 1(2009): 1-7, esp. figs. 4a and 4b, see: https://edoc.hu-berlin.de/bitstream/handle/18452/7570/rath.pdf (accessed 15 August 2021); also cited in Horst Brendel, Image Acts: A Systematic Approach to Visual Agency (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2021), 287, fig. 199. See also Charles H. Carman, Leon Battista Alberti and Nicholas Cusanus: Toward an Epistemology of Vision for Italian Renaissance Art and Culture (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014), 3-9.

38 De Vere-Vasari, Vita of Andrea Castagno, 1:543.

杂志排行

Journal of Literature and Art Studies的其它文章

- Brief Discussion on the Disappearance of the Aura of Art Works in Current Era

- The Relationship Between Online Participation and Academic Achievements for Students Majoring in Business English

- On Combining Ideological and Political Education with English-Chinese Translation Teaching

- A Skopos Theory-based Study of Translation Principles of Traditional Chinese Medicine Decoctions

- A Comparative Study of Conceptual Structures of Metaphor and Metonymy from a Cognitive Perspective

- Mandarin Mingled by Cantonese:A Phenomenon of Language Variation