发酵剂对发酵香肠食用品质的影响及其在不同直径香肠中的应用

2020-12-28荣良燕杨娟春赵拎玉钟桂霞杨鹏李儒仁

荣良燕 杨娟春 赵拎玉 钟桂霞 杨鹏 李儒仁

摘 要:以商业发酵剂(木糖葡萄球菌+戊糖片球菌)为对照组,不同发酵剂组合(木糖葡萄球菌+副干酪乳杆菌、木糖葡萄球菌+戊糖片球菌+副干酪乳杆菌)为实验组,通过对发酵香肠水分含量、pH值、水分活度、色泽、质地、风味和感官品质等指标进行测定,确定最佳发酵剂及适宜发酵的香肠直径。结果表明:相较于商业发酵剂,木糖葡萄球菌与副干酪乳杆菌组合发酵的香肠总体可接受性相对较高,且庚醛、1-辛烯-3-醇、乳酸乙酯、戊酸乙酯、癸酸乙酯、2-甲基丙酸乙酯等愉悦风味物质为该组独有,其特征主要表现为更加浓郁的清新味、甜香味、果香味和花香味;适宜的直径(21 mm)、水分含量((25.40±0.00)%)和硬度((2 812.46±767.93)g)以及相对较高的pH值(pH 5.57±0.02)是该组发酵香肠口感显著高于其他2 组的重要原因。因此,木糖葡萄球菌与副干酪乳杆菌组合发酵的小直径香肠食用品质最佳。

关键词:戊糖片球菌;木糖葡萄球菌;副干酪乳杆菌;质地;风味

Abstract: Fermented sausages were manufactured with two different mixed starter cultures: Staphylococcus xylosus + Lactobacillus paracasei, and Staphylococcus xylosus + Pediococcus pentosaceus + Lactobacillus paracasei. A commercial starter culture (Staphylococcus xylosus + Pediococcus pentosaceus) was used as the control. The moisture content, pH value, water activity, color, texture, flavor and sense quality of fermented sausages were determined. By doing so, we aimed to determine the optimal starter culture and diameter of fermented sausages. The results showed that the overall acceptability of the sausage fermented with Staphylococcus xylose + Lactobacillus paracasei was higher than that of the control group, and it was found to exclusively contain heptanal, 1-octene-3-alcohol, ethyl lactate, ethyl pentanoate and ethyl decanoate, which contributed to a pleasant flavor characterized by refreshing, sweet, fruity and floral aromas. The mouth-feeling of this sausage was significantly superior to that of the two other groups because of its appropriate diameter (21 mm), moisture content ((25.40 ± 0.00)%) and hardness (2 812.46 ± 767.93) g) as well as higher pH value (pH 5.57 ± 0.02). Therefore, the eating quality of small-diameter sausages fermented by combination of Staphylococcus xylose and Lactobacillus paracei was the best.

Keywords: Pediococcus pentosaceus; Staphylococcus xylosus; Lactobacillus paracasei; texture; flavor

DOI:10.7506/rlyj1001-8123-20200810-192

中圖分类号:TS251.5 文献标志码:A 文章编号:1001-8123(2020)10-0033-07

传统自然发酵香肠是一种由微生物转化利用碎肉中蛋白质、脂肪、碳水化合物等营养组分形成的营养价值较高、风味独特的中高档发酵肉制品[1-2]。自然发酵香肠在欧美地区拥有很高的市场占有率,2 000多年的消费历史和卓越的品质是保证其销量的重要原因[3]。近10 年来,消费升级驱动大量进口发酵香肠入驻中国市场,销量逐年攀升,但传统自然发酵香肠的加工严重依赖环境、气候等因素,且存在季节依赖性强、发酵周期较长等问题[4-5],导致自然发酵香肠的销量存在供不应求的局面。采用进口发酵剂和发酵工艺是解决该问题的主要策略,这在一定程度上弥补了自然发酵的缺陷[6],但相较于自然发酵的高档产品,接种发酵的切片即食类干腌发酵香肠在风味上仍存在较大差距[7]。

发酵肉制品加工一般依据菌种快速酸化、改善风味[8]等发酵特性,将筛选出的乳酸菌和凝固酶阴性球菌复配为商业发酵剂[9-12]。目前普遍选择清酒乳杆菌和木糖葡萄球菌(Staphylococcus xylosus)[13]、植物乳杆菌和木糖葡萄球菌[14-15]、戊糖片球菌(Pediococcus pentosaceus)和木糖葡萄球菌[16]等复配作为商业发酵剂,但其获得的产品风味始终不及自然发酵。此外,部分具有益生潜力的干酪乳杆菌[17-18]、鼠李糖乳杆菌[19]等也被用于改良发酵香肠的风味,但其改善效果有限。因此,有必要寻找更适宜的发酵剂,解决现有商业发酵剂产香能力不足的问题。

采用IBM SPSS Statistics 19软件进行数据统计分析;采用方差分析确定差异显著性,P<0.05表示差异显著。

2 结果与分析

2.1 不同发酵剂和香肠直径对发酵香肠感官品质的影响

发酵香肠的感官特征是影响消费者喜好程度的重要因素。由图1可知,A35和A21组发酵香肠总体可接受性较高,其风味特征为清新味、甜香味和果香味较浓郁,上述风味不足可能是导致B35、C35和B21、C21组发酵香肠总体可接受性相对较低的重要原因。各处理组之间总体可接受性具有上述差异的主要原因在于肠体中微生物和不同的发酵剂组合利用肉中脂肪和蛋白质的代谢性能不同,产生的代谢产物不同,导致感官特性产生差异[27]。

2.2 不同发酵剂和香肠直径对发酵香肠pH值、水分含量和aw的影响

发酵香肠的总体可接受度与其pH值紧密相关,相对较高的pH值(5.68~5.89)更容易获得较高的感官评分[28]。由表2可知,相较于其余组,总体可接受性较高的A35、A21组发酵香肠pH值相对较高(pH>5.5),这与发酵香肠中菌种的组合方式紧密相关,说明B、C组的戊糖片球菌酸化能力相对较强[29],且副干酪乳杆菌与其共同接种产生的代谢竞争有助于减少发酵体系中酸性代谢产物的积累,从而提高发酵香肠的pH值[30]。

发酵香肠的水分含量相对较低时,由于其具备更好的硬度和咀嚼度,更容易获得消费者的青睐[31]。各组发酵香肠的水分含量为16.60%~25.40%,属于典型的干腌发酵香肠[30]。相较于B、C组,总体可接受性较高的A组发酵香肠水分含量相对较高(19.07%、25.40%)。

各组发酵香肠的aw为0.73~0.76,在小直径发酵香肠中,不同发酵剂组间aw差异显著(P<0.05),相较于C21组,A21和B21组aw较高,而在大直径发酵香肠中,不同发酵剂组间aw无显著差异。这一结果与Mohtanali等[29]的研究结果相似,发酵环境中引入酸化能力较强的戊糖片球菌更容易降低环境pH值,进而引起蛋白质凝胶化程度上升及持水能力下降[32],最终导致发酵香肠加工过程中内部水分向外迁移较多[30],这可能是pH值较低处理组水分含量和aw较低的主要原因。

2.3 不同发酵剂和香肠直径对发酵香肠色泽的影响

发酵香肠的色泽特征是影响消费者喜好度的重要因素之一。由表3可知,相较于其余组,A35和B35组发酵香肠L*显著较高(P<0.05),这与A35和B35组香肠成熟结束后的水分含量相对较高有关。在小直径发酵香肠中,不同发酵剂组间L*差异显著(P<0.05),但感官评分差异不显著,这一结果与Chen Jianshe[33]的研究结果类似。此外,大、小直径香肠的a*分别为13.89~16.31、11.89~14.14,b*分别为5.20~7.94、5.36~6.58,且不同组间均存在显著差异(P<0.05),但感官评价人员很难感受这些细微差异,后期有待建立较为系统的方法将色泽测定结果与感官评价结果综合起来进行分析。

2.4 不同发酵剂和香肠直径对发酵香肠质构特性的影响

质构是发酵香肠成熟程度的重要指标,通过硬度、弹性、内聚性和咀嚼度4 个指标来评判香肠的质构品质特性。由表4可知,B、C组发酵香肠的硬度显著高于A组(P<0.05),其原因可能与B、C组接种戊糖片球菌的产酸能力有关,相对较低的pH值更易导致肉类蛋白的变性和持水力下降,使发酵成熟过程中香肠的内部形成密度和硬度更大的凝胶网络结构[34],从而使香肠的硬度增大。在弹性方面,各组发酵香肠间均无显著差异。在大直径香肠中,不同发酵剂组间内聚性差异显著(P<0.05)。B35组的咀嚼度均高于其他组,但感官评价人员并不能完全感受到细微的差异,因此在后续的产品品质分析中,有待建立更为合理的方法综合分析感官属性和产品属性。

2.5 不同发酵剂和香肠直径对发酵香肠挥发性风味物质的影响

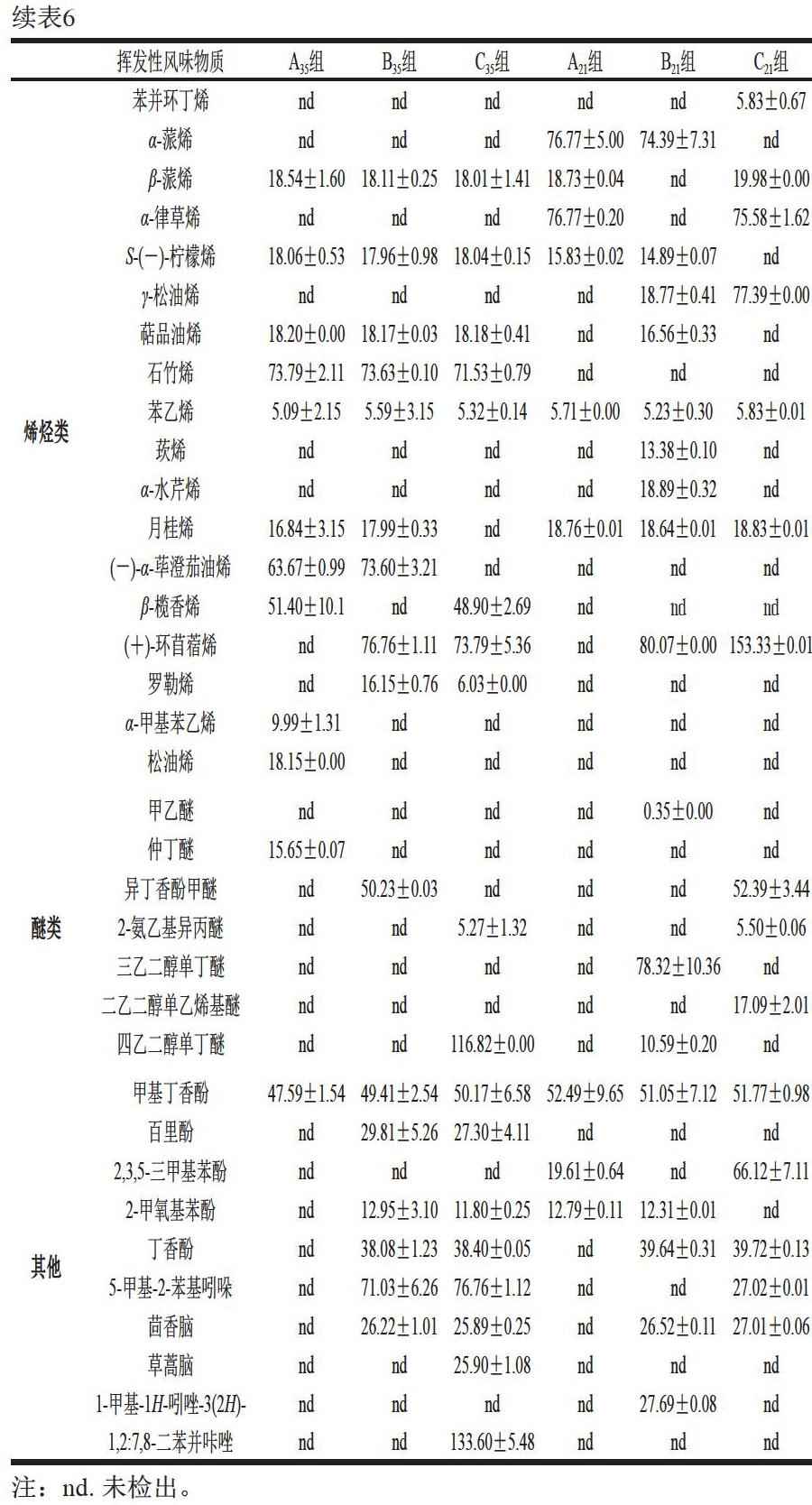

由表5可知,各组发酵香肠中醛类、醇类、酯类、烯烃类相对含量较高。相较于其余组,A35组发酵香肠含有较多醛类(15.66%),A21组发酵香肠中醇类、酯类相对含量较高,分别为15.75%和29.90%。

由表6可知,采用木糖葡萄球菌和副干酪乳杆菌组合发酵的A35和A21组发酵香肠含有更多的庚醛、1-辛烯-3-醇、乳酸乙酯、戊酸乙酯、癸酸乙酯、2-甲基丙酸乙酯等风味物质,清新味、甜香味、果香味和花香味更加浓郁[35-36],不但能够形成已报道的乙酸乙酯、己酸乙酯等重要风味物质[37-38],还可以形成乳酸乙酯、戊酸乙酯、癸酸乙酯。B35、C35和B21、C21组也产生了己酸乙酯、丁酸甲酯、辛酸乙酯等酯类物质。占比较高的醛类、醇类以及种类较多的乳酸乙酯、戊酸乙酯、癸酸乙酯等酯类物质是A35、B21组发酵香肠总体可接受性较高的重要原因。这可能是由于肠体中的微生物和木糖葡萄球菌与副干酪乳杆菌利用肉中的脂肪和蛋白质产生酸类和醇类物质,且经过酯化反应形成具有特殊香气的乳酸乙酯、戊酸乙酯、癸酸乙酯等酯类物质[7]。

3 结 论

相较于市售商业发酵剂,采用木糖葡萄球菌和副干酪乳杆菌组合发酵制作的发酵香肠总体可接受性相对较高,其色泽暗红(L* 32.08±0.08、a* 14.14±0.15)、组织紧密、pH 5.57±0.02、水分含量(25.40±0.00)%、硬度较小((2 812.46±767.93) g)、咀嚼感较好,具有明显的清新味、甜香味、果香味和花香味,且检测到独有的挥发性风味物质包括庚醛、1-辛烯-3-醇、乳酸乙酯、戊酸乙酯、癸酸乙酯、2-甲基丙酸乙酯等。另外,小直徑香肠的总体可接受性较高,是适宜发酵的香肠直径大小。由此可知,木糖葡萄球菌与副干酪乳杆菌组合发酵的小直径香肠食用品质最优,上述结果对于开发消费者喜好的新型发酵香肠具有一定的指导意义。

参考文献:

[1] CORRAL S, SALVADOR A, BELLOCH C, et al. Effect of fat and salt reduction on the sensory quality of slow fermented sausages inoculated with Debaryomyces hansenii yeast[J]. Food Control, 2014, 45(3): 1-7. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.04.013.

[2] SIDIRA M, GALANIS A, NIKOLAOU A, et al. Evaluation of Lactobacillus casei ATCC 393 protective effect against spoilage of probiotic dry-fermented sausages[J]. Food Control, 2014, 42(3): 315-320. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.02.024.

[3] 劉蒙佳, 周强, 许美纯, 等. 不同配料及发酵剂对发酵香肠品质特性的影响[J]. 中国调味品, 2018, 43(1): 17-25. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-9973.2018.01.004.

[4] PARAMITHIOTIS S, DROSINOS E H, SOFOS J N, et al. Fermentation: microbiology and biochemistry[M]. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. DOI:10.1002/9780813820897.ch9.

[5] BASSI D, PUGLISI E, COCCONCELLI P S. Comparing natural and selected starter cultures in meat and cheese fermentations[J]. Current Opinion in Food Science, 2015, 2: 118-122. DOI:10.1016/j.cofs.2015.03.002.

[6] FADDA S, L?PEZ C, VIGNOLO G. Role of lactic acid bacteria during meat conditioning and fermentation: peptides generated as sensorial and hygienic biomarkers[J]. Meat Science, 2010, 86(1): 66-79. DOI:10.1016/j.meatsci.2010.04.023.

[7] FERROCINO I, BELLIO A, GIORDANO M, et al. Shotgun metagenomics and volatilome profile of the microbiota of fermented sausages[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2018, 84(3): e02120-17. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02120-17.

[8] BIS-SOUZA C V, BARBA F J, LORENZO J M, et al. New strategies for the development of innovative fermented meat products: a review regarding the incorporation of probiotics and dietary fibers[J]. Food Reviews International, 2019, 35(5): 467-484. DOI:10.1080/87559129.2019.1584816.

[9] FONSECA S, OUOBA L I I, FRANCO I, et al. Use of molecular methods to characterize the bacterial community and to monitor different native starter cultures throughout the ripening of Galician Chorizo[J]. Food Microbiology, 2013, 34(1): 215-226. DOI:10.1016/j.fm.2012.12.006.

[10] LEROY F, VUYST L D. Lactic acid bacteria as functional starter cultures for the food fermentation industry[J]. Trends in Food Science and Technology, 2004, 15(2): 67-78. DOI:10.1016/j.tifs.2003.09.004.

[11] RAVYST F, VUYST L D, LEROY F. Bacterial diversity and functionalities in food fermentations[J]. Engineering in Life Sciences, 2012, 12(4): 356-367. DOI:10.1002/elsc.201100119.

[12] SAMELIS J, STAVROPOULOS S, KAKOURI A, et al. Quantification and characterization of microbial population associated with naturally fermented Greek dry salami[J]. Food Microbiology, 1994, 11(6): 447-460. DOI:10.1006/fmic.1994.1050.

[13] PASINI F, SOGILA F, PETRACCI M, et al. Effect of fermentation with different lactic acid bacteria starter cultures on biogenic amine content and ripening patterns in dry fermented sausages[J]. Nutrients, 2018, 10(10): 1497. DOI:10.3390/nu10101497.

[14] ESSID I, HASSOUNA M. Effect of inoculation of selected Staphylococcus xylosus and Lactobacillus plantarum strains on biochemical, microbiological and textural characteristics of a Tunisian dry fermented sausage[J]. Food Control, 2013, 32(2): 707-714. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.02.003.

[15] PAVLI F G, ARGYRI A A, CHORIANOPOULOS N G, et al. Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum L125 strain with probiotic potential on physicochemical, microbiological and sensorial characteristics of dry-fermented sausages[J]. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 2019, 118: 108810. DOI:10.1016/j.lwt.2019.108810.

[16] WANG Xinhui, REN Hongyang, WANG Wei, et al. Effects of inoculation of commercial starter cultures on the quality and histamine accumulation in fermented sausages[J]. Journal of Food Science, 2015, 80(2): 377-384. DOI:10.1111/1750-3841.12765.

[17] BIS-SOUZA C V, PENNA A L B, BARRETTO A C D S. Applicability of potentially probiotic Lactobacillus casei in low-fat Italian type salami with added fructooligosaccharides: in vitro screening and technological evaluation[J]. Meat Science, 2020, 168: 108186. DOI:10.1016/j.meatsci.2020.108186.

[18] COELHO S R, LIMA L A, MARTINS M L, et al. Application of Lactobacillus paracasei LPC02 and lactulose as a potential symbiotic system in the manufacture of dry-fermented sausage[J]. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 2019. DOI:10.1016/j.lwt.2018.12.045.

[19] BIS-SOUZA C V, PATEIRO M, RUB?N D, et al. Impact of fructooligosaccharides and probiotic strains on the quality parameters of low-fat Spanish Salchichón[J]. Meat Science, 2019, 159: 107936. DOI:10.1016/j.meatsci.2019.107936.

[20] NILSEN A, R?DBOTTEN M, PRUSA K, et al. Sensory analyses-general considerations[M]. 2nd ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014: 189-194. DOI:10.1002/9781118522653.ch22.

[21] ?KRLEP M, ?ANDEK-POTOKAR M, BATOREK-LUKA? N, et al. Aromatic profile, physicochemical and sensory traits of dry-fermented sausages produced without nitrites using pork from Kr?kopolje pig reared in organic and conventional husbandry[J]. Animals, 2019, 9(2): 55. DOI:10.3390/ani9020055.

[22] 中華人民共和国国家卫生和计划生育委员会. 食品安全国家标准 食品中水分的测定: GB 5009.3—2016[S]. 北京: 中国标准出版社, 2016: 1-2.

[23] P?REZ-ALVAREZ J A, SAYAS-BARBER? M E, FERN?NDEZ-L?PEZ J, et al. Physicochemical characteristics of Spanish-type dry-cured sausage[J]. Food Research International, 1999, 32(9): 599-607. DOI:10.1016/S0963-9969(99)00104-0.

[24] 中華人民共和国国家卫生和计划生育委员会. 食品安全国家标准 食品中水分活度的测定: GB 5009.238—2016[S]. 北京: 中国标准出版社, 2016: 4-5.

[25] OLIVARES A, NAVARRO J L, SALVADOR A, et al. Sensory acceptability of slow fermented sausages based on fat content and ripening time[J]. Meat Science, 2010, 86(2): 251-257. DOI:10.1016/j.meatsci.2010.04.005.

[26] CORRAL S, SALVADOR A, FLORES M. Salt reduction in slow fermented sausages affects the generation of aroma active compounds[J]. Meat Science, 2013, 93(3): 776-785. DOI:10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.11.040.

[27] ERCOLINI D. Molecular techniques in the microbial ecology of fermented foods[M]. New York: Springer, 2008. DOI:10.1007/978-0-387-74520-6.

[28] 李儒仁, 钟桂霞, 赵拎玉, 等. 市售西班牙自然发酵香肠的食用品质特征分析[J]. 肉类研究, 2020, 34(6): 64-71. DOI:10.7506/rlyj1001-8123-20200220-045.

[29] MONTANARI C, GATTO V, TORRIANI S, et al. Effects of the diameter on physico-chemical, microbiological and volatile profile in dry fermented sausages produced with two different starter cultures[J]. Food Bioscience, 2017, 22: 9-18. DOI:10.1016/j.fbio.2017.12.013.

[30] TOLDR? F, HUI Y H. Dry-fermented sausages and ripened meats: an overview[M]. 2nd ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014: 1-6. DOI:10.1002/9781118522653.ch1.

[31] STAJI? S, STANI?I? N, LEVI? S, et al. Physico-chemical characteristics and sensory quality of dry fermented sausages with flaxseed oil preparations[J]. Polish Journal of Food and Nutrition Sciences, 2018, 68(4): 367-375. DOI:10.2478/pjfns-2018-0006.

[32] XIAO Yaqing, LIU Yingnan, CHEN Conggui, et al. Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum and Staphylococcus xylosus on flavour development and bacterial communities in Chinese dry fermented sausages[J]. Food Research International, 2020, 135: 109247. DOI:10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109247.

[33] CHEN Jianshe. It is important differentiate sensory property from the material property[J]. Trends in Food Science and Technology, 2020, 96: 268-270. DOI:10.1016/j.tifs.2019.12.014.

[34] XU Yanshun, XIA Wenshui, YANG Fang, et al. Effect of fermentation temperature on the microbial and physicochemical properties of silver carp sausages inoculated with Pediococcus pentosaceus[J]. Food Chemistry, 2010, 118(3): 512-518. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.05.008.

[35] MARCO A, NAVARRO J L, FLORES M. Quantification of selected odor-active constituents in dry fermented sausages prepared with different curing salts[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2007, 55: 3058-3065. DOI:10.1021/jf0631880.

[36] STAHNKE L H. Dried sausages fermented with Staphylococcus xylosus at different temperatures and with different ingredient levels. Part II. Volatile components[J]. Meat Science, 1995, 41(2): 193-209. DOI:10.1016/0309-1740(94)00069-J.

[37] BIS-SOUZA C V, PATERIO M, RUB?N D, et al. Volatile profile of fermented sausages with commercial probiotic strains and fructooligosaccharides[J]. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 2019, 56: 5465-5473. DOI:10.1007/s13197-019-04018-8.

[38] ANDRACE M J, C?RDOBA J J, CASADO E M, et al. Effect of selected strains of Debaryomyces hansenii on the volatile compound production of dry fermented sausage “salchichón”[J]. Meat Science, 2010, 85(2): 256-264. DOI:10.1016/j.meatsci.2010.01.009.