New insight into dental epithelial stem cells: Identification, regulation, and function in tooth homeostasis and repair

2020-12-22LuGanYingLiuDiXinCuiYuePanMianWan

Lu Gan, Ying Liu, Di-Xin Cui, Yue Pan,Mian Wan

Lu Gan, Ying Liu, Di-Xin Cui, Yue Pan,State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases & National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases & Department of Pediatric Dentistry, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan Province, China

Mian Wan,State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases & National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases & Department of Cariology and Endodontics, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan Province, China

Abstract

Key Words: Dental epithelial stem cells; Tissue engineering; Label-retaining cells; Lineage tracing; Single-cell sequencing

INTRODUCTION

Tooth enamel, the most highly mineralized tissue in the human body, consists of hydroxyapatite organized into enamel rods and inter-rods which are interwoven, therefore serving as a protective covering for the tooth crown. During enamel formation, inner enamel epithelial cells in the enamel organ differentiate into enamelforming ameloblasts, which secrete enamel matrix and create an extracellular environment for mineralization[1-4]. These cells commit apoptosis once the enamel formation is accomplished and the tooth erupts into the oral cavity[5]. The loss of ameloblasts and neighboring environment renders enamel an acellular and nonvital tissue that, when insulted by dental caries or trauma, is incapable of repair or renewal. To restore the missing enamel tissue, current treatment is limited to using acid-etching techniques and artificial materials such as resin, amalgam, and porcelain, which are not perfect due to frequent microleakage, limited life span, or inherent inability to fully restore its function[6-8].

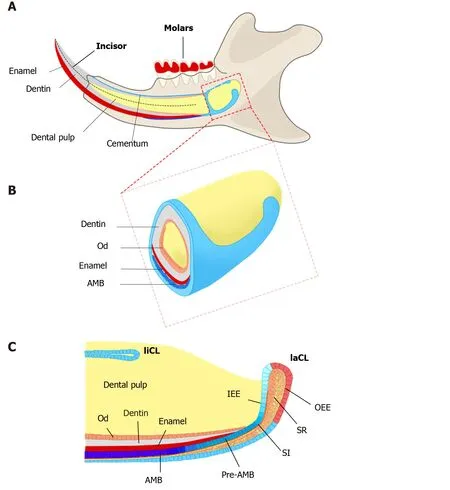

One potential remedy for this is to construct natural enamel. Enamel–dentin complex structure has been detected on polyglycolic acid fiber mesh using dissociated porcine third molar tooth germ cells, suggesting tissue engineering as an alternative strategy to regenerate enamel[9]. The classic tissue engineering relies on three elements, including stem cells, suitable scaffolds, and bioactive molecules to initiate a sequence of events inducing tissue formation[10,11]. However, unlike successful implementation of tissue engineering in other dental tissues, such as dentin and pulp regeneration, enamel tissue engineering is hindered since ameloblasts and dental epithelial stem cells (DESCs) are lost when the tooth erupts[5]. Consequently, the generation of potent and viable DESCs would be a major step toward promising enamel tissue engineering[12]. Interestingly, nature has provided us a good example, the rodent incisor, which grows continuously throughout the animal’s life[13]. Haradaet al[14]have identified DESCs at the proximal end of mouse incisors, in a structure named the labial cervical loop (laCL). These cells can self-renew and differentiate into enamel-secreting ameloblasts and the other supporting dental epithelial lineages[15-18]. Owing to the ready accessibility of mouse DESCs and the wide availability of related transgenic mouse lines, mouse incisors serve as an ideal system to explore the identity and heterogeneity of dental epithelial stem/progenitor cells. The continuous replenishment of enamel tissue is fueled by the DESCs, making mouse incisors an excellent model to uncover the regulatory mechanisms underlying enamel formation[19](Figure 1). Moreover, studying how the homeostasis and repair are maintained by DESCs in mouse incisors can help us answer the open question regarding the therapeutic development of enamel engineering.

In the present review, we update the current understanding about the identification of DESCs in mouse incisors and summarize the regulatory mechanisms of enamel formation driven by DESCs. The roles of DESCs during homeostasis and repair are also discussed, which could improve our knowledge regarding enamel tissue engineering.

Figure 1 Schematics of adult mouse incisor and cervical loops.

IDENTIFICATION OF DESCS

Classical model

In the classical model of tissue supported by stem cells, rare slow-cycling stem cells, which divide infrequently, contribute to the production of active-cycling transitamplifying (TA) cells, which then generate all the related lineages[20-23]. Therefore, the stem cells in the adult tissue are always identified by their characteristics, for instance, their quiescent feature and their potential of uni- or multilineage differentiation[21].

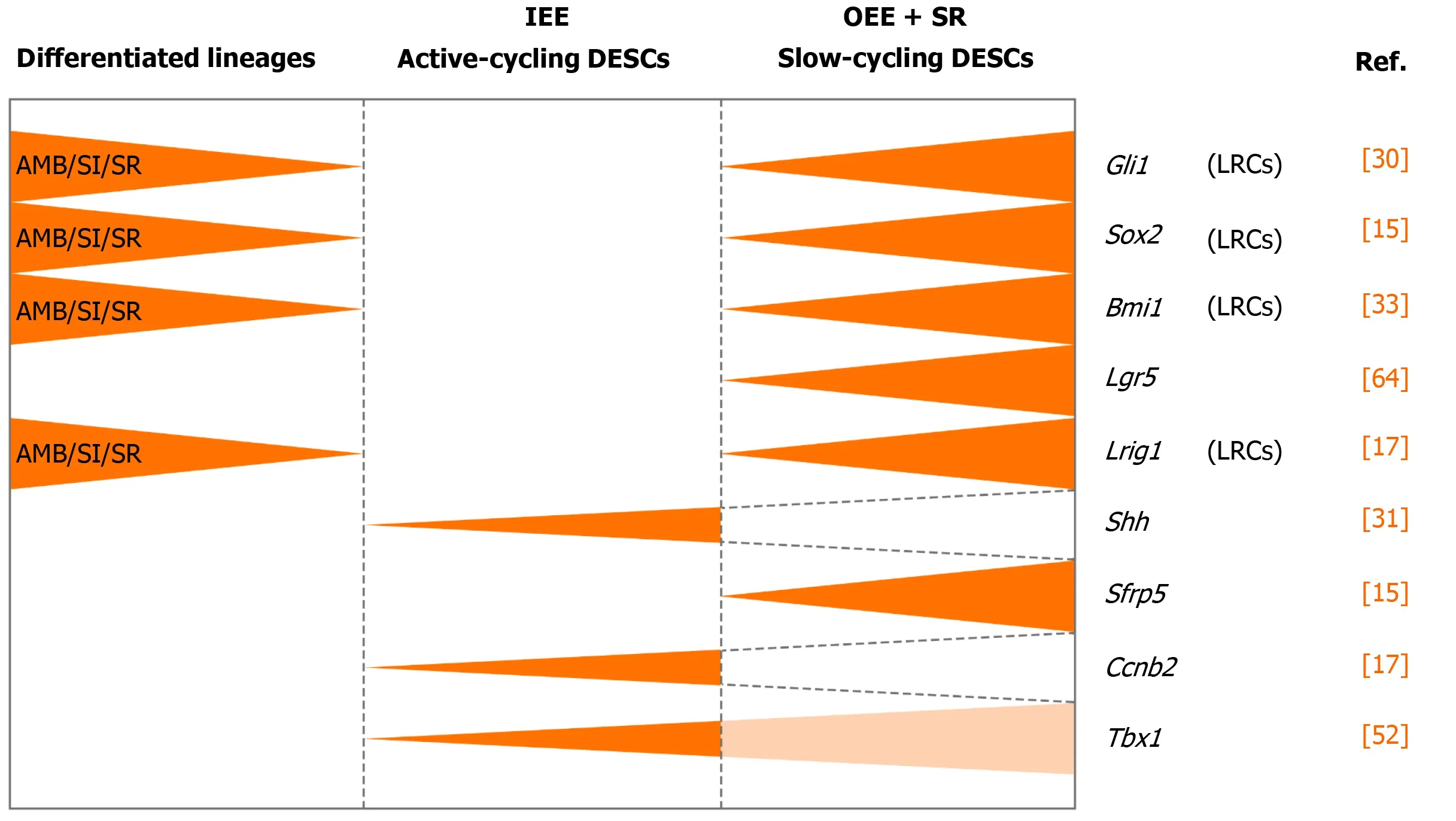

A credible approach to locate the stem cell niche in adult tissue is to take the benefit of their quiescent property by positioning the distribution of label-retaining cells (LRCs)[21]. LRCs are capable of retaining DNA synthesis labels, including tritiated thymidine (3H-thymidine) and 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine (BrdU), after a long-term chase[24,25]. Active-cycling cells, such as TA cells, remove the DNA label following cell divisions within a short time. On the contrary, the quiescent stem cells retain the label during a long chasing period owing to their infrequent division[21-23]. LRCs have been confirmed as stem cells in various tissues and organs, such as the epidermis, intestine, and mammary gland[26-28]. With one administration of 3H-thymidine, an early study showed proliferating cells in the adult rat enamel organ, which exited the cell cycle and migrated distally. After 32 d, the cells retaining the label were detected in the outer enamel epithelium (OEE) and underlying stellate reticulum (SR) of laCL, suggesting the existence of DESCs at the proximal end of the laCL[29,30]. To detect LRCsin vivo, the neonatal mice were pulsed with BrdU, to label the cycling cells in the dental epithelium at the time of tissue expansion and subsequently to identify the LRCs that rarely divide and retain the label till adulthood. The distribution of BrdU+LRCs in the OEE and underlying SR confirmed the presence of slow-cycling cells in laCL[14,31]. Later, this assumption was demonstrated withK5Tta; H2B-GFPmice, in which the expression of doxycycline-repressibleH2B-GFPis regulated by the keratin 5 promoter[32]. All dental epithelial lineages uniformly express green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the absence of doxycycline administration. Following 2 mo administration of doxycycline, H2B-GFP-retaining cells were observed in the same compartments, suggesting that putative DESCs were present in these compartments and might have contributed to the continuous growth of the incisor enamel[33,34].

To further assess the uni- or multilineage differentiation potential of putative stem cells, the cells and their progeny are permanently genetically marked and chased using lineage tracing, an essential strategy in the identification of stem cells in adult mammalian tissue[21,35]. Genetic lineage tracing in mice is preferably achieved with the Cre-loxP system. In this system, the Cre specifically activates the reporter in cells upon the control of the tissue- or cell-specific promoter, by excising theloxP-STOP-loxPsequence. With inducible recombination (Cre recombinase is fused to estrogen receptor), the Cre recombinase activity can be manipulated temporally and spatially with tamoxifen[36-38]. The application of inducible Cre for lineage tracing has provided maximum information about all the progeny of the stem cells in postnatal tissue. With CreER controlled byGli1promoter (GliCreER),Gli1+cells residing in the LRCs region (OEE and underlying SR) have been demonstrated to be capable of generating functional ameloblasts and supporting epithelial lineages, such as stratum intermedium (SI) cells[31]. The distribution ofBmi1+cells in laCL is consistent with that of LRCs andGli1+cells. Similarly,Bmi1+cells also give rise to enamel-producing ameloblasts and neighboring SI cells[33]. UnlikeGli1andBmi1,Sox2has a broader expression domain, which expands both distally and proximally in the laCL. Genetic lineage tracingin vivohas revealed thatSox2+cells could generate all the mouse incisor epithelial lineages[15]. Later,Lrig1has been proposed as a putative stem cell marker by gene coexpression module analysis. Moreover,Lrig1+cells have been shown to contribute to dental epithelial lineagesvia in vivolineage tracing[17]. These previous studies have constructed the classical model of enamel renewal, in which slow-cycling DESCs, residing in the OEE and underlying SR of the laCL, regularly move to the inner enamel epithelium (IEE) and generate active-cycling TA cells[16]. These activecycling cells migrate distally, exit the cell cycle, and differentiate into enamelproducing ameloblasts. However, identification of cell types, properties, and cellular relationships remains unknown in this classical model. Furthermore, the latest study has shown that the expression of the putative DESCs markers, includingBmi1,Gli1, andSox2, are broader than we expected, since they have been detected in the IEE as well, which unravels the limitation of the currently available genetic strategies (Figure 2).

Updated model

The previous studies mentioned above characterized stem cells based on the known properties, which would inevitably introduce researchers’ preconceptions, such as significant signaling pathways certified in the putative stem cell niche[39]. Therefore, unbiased technology is desired to identify cells and characterize cells with new clusters of markers. Single-cell sequencing, in particular, mRNA sequencing from single cells (scRNA-seq), contributes to the unbiased profiling of cells from tissues and organs[40-42]. Generally, single cells are isolated and assigned to a specific barcode; thus, gathered mRNA can be sequenced and reassigned to its cellular origin. According to the transcriptomes, cells are divided into groups with unsupervised clustering[43]. This scRNA-seq shows a series of advantages in uncovering heterogeneity within the population which was considered to be homogeneous, discovering novel and rare cell types, and raveling the relationships between cell types.

Figure 2 Identification of dental epithelial stem cells in mouse incisor.

Shariret al[18]performed scRNA-seq of sorted dental epithelial cells to resolve the cellular heterogeneity and lineage dynamics of the adult incisor epithelium in an unbiased manner. Single cells from mouse incisors were generated and sequenced. The high-dimensional, whole-transcriptome data were visualized using SPRING[18], which is suitable for analyzing differentiation trajectories as maintaining relationships of cells with the similar transcriptome. Mouse incisor epithelial cells are divided into three groups, including cycling cells (class 1), ameloblast lineages (class 2), and nonameloblast epithelial cells (class 3)[17]. With the expression of cell-cycle markers likeCdc20andCcnb2, class 1 cells have the majority of dividing and cycling cells, located in the IEE and adjacent SI region. Moreover, class 1 cells maintain active self-renewal as their transcriptomes have shown successive phases of the cell cycle, and several cells return to their original state at the end of the cell cycle. Signatures reflecting classes 2 and 3 populations have also been observed in class 1 cell populations, suggesting that progenitors are cycling with upregulated expression of differentiation genes. Combined with differentiation trajectories and kinetics experiments, class 1 houses progenitor cells considered as the root, which produces cells of classes 2 and 3[18]. Therefore, distinct from the classical views, an updated dynamic model of stem cells in mouse incisors reveals that the IEE (class 1) possesses active cycling stem cells that differentiate into both the functional ameloblasts and the surrounding nonameloblast epithelial lineages (classes 2 and 3).

Difference between the classical and updated models

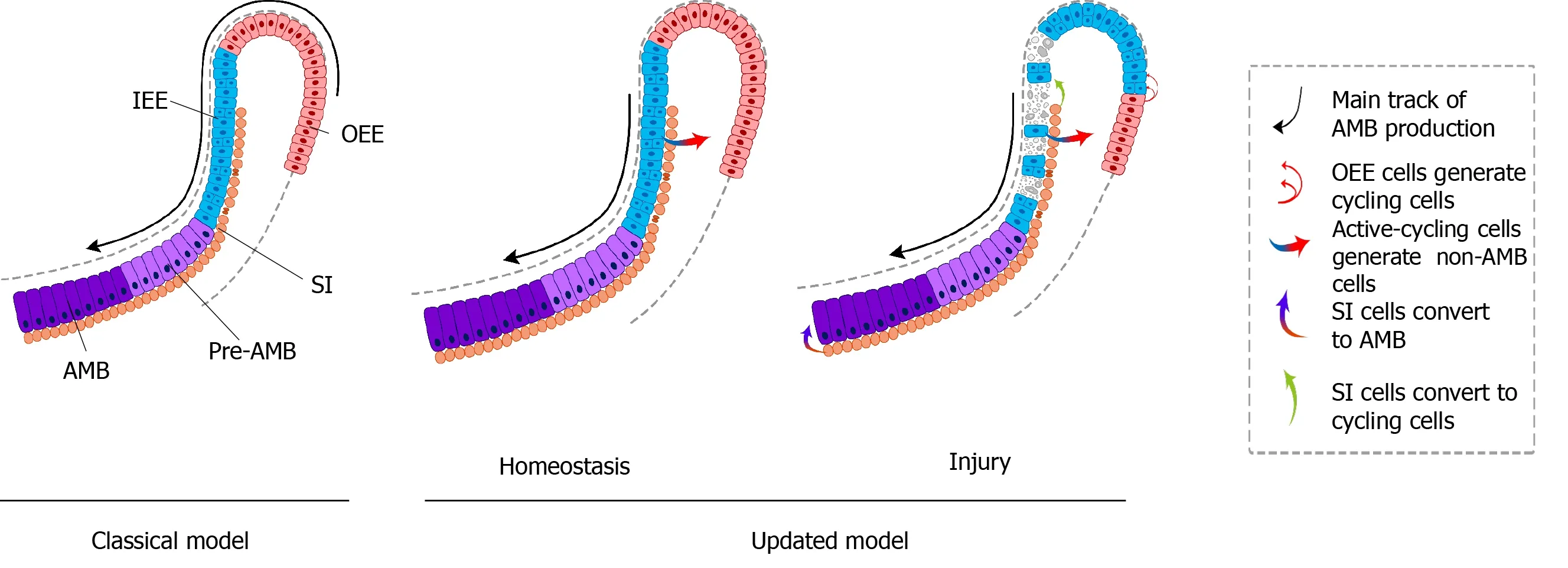

The classic model of DESCs in mouse incisors is similar to that of hematopoietic stem cells. The homeostasis of mouse incisor enamel is fueled by the quiescent stem cells in the OEE and underlying SR of the laCL[13-17,19]. These slow-cycling cells produce TA cells in the IEE that undergo limited divisions before terminal differentiation (Figure 3A). Even though scientists stick to this concept for a long time, the concept is still incapable of accounting for the great demand of ameloblasts in daily production of enamel. In this model, DESCs were identified with LRCs and lineage tracing of specific stem cell marker candidates, includingSox2,Bmi1,Gli1, andLrig1. On the contrary, the novel model is based on scRNA-seq, an unbiased method. The dental epithelial cells in laCL can be divided into three different groups. The daily production of enamel is supported by a group of actively cycling progenitor cells in the IEE, which are responsible for the production of ameloblasts and nonameloblast epithelial lineages, including the OEE and underlying SR, which are considered as DESCs in the classic model[18](Figure 3B). Previously established stem cell markers, includingSox2,Bmi1,Gli1, andLrig1, are not expressed specifically in any groups of the updated model.

Figure 3 Classical and updated models of dental epithelial stem cells in mouse incisors.

REGULATORY NETWORK OF DESCS IN MOUSE INCISORS

Genetic regulation

The proliferation and differentiation of DESCs are regulated by genetic regulatory signals in a temporospatial manner[39]. Surrounding dental mesenchymal cells provide essential signals for maintenance and differentiation of DESCs[44]. To date, several signaling pathways have been found to be important for the steady state of the DESCs niche and subsequent differentiation in mouse incisors[16,19]. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling was first put forward.Fgf3,Fgf9, andFgf10are key mesenchymal signals for stimulating the proliferation of DESCs in the developing cervical loops[30,45-48]. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling participates in DESC maintenance and TA cell proliferation by regulating the activity of FGF signaling[47,48]. The expression ofFgf3andFgf10and the number of BrdU+LRCs are markedly reduced in the laCL of mice with mutation of theAlk5gene, which is responsible for encoding the TGF-β type I receptor[48]. The reduction ofFgf3/10expression by TGF-β type II receptor (Tgfbr2) deletion in mesenchyme-promoted differentiation of DESCs results in wavy mineralized structure formation[49].Sproutygenes, which encode the intracellular antagonists of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling, ensure lineage differentiation of DESCs through the FGF signaling pathway[50]. OnceSproutygenes are deleted, the inhibitory signal is removed, leading to increased sensitivity toFgf3/10expression in both liCL and laCL as well as the adjacent mesenchyme[51]. The inhibitory effect of Sprouty protein on FGF signaling functions is mediated by changing the expression ofTBX1andBCL11Bindirectly in theSpry4-/-mice[52,53]. The removal ofBCL11Baffects the differentiation and proliferation of DESCs, reduces the size of the laCL, and shortens the zone of ameloblast progenitors[53]. Conversely, an allele ofBCL11Bpromotes the proliferation of TA cells, thus ensuring a stable number of DESCs[54]. Caoet al[55]have demonstrated thatTBX1regulates DESCs by suppressing the transcriptional activity ofPitx2which is in connection with a cell cycling inhibitor p21. The downstream of FGF signaling has been explored by Goodwinet al[56]. Ras signaling is activated after FGFs bind to receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and then regulate the proliferative activity of DESCs through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathways. Further evidence about the role of MAPK and PI3K in amelogenesis has been proposed through a mouse incisor model of Ras dysregulation[57].

Another important signaling pathway is Hedgehog (Hh), which is essential for maintaining epithelial cell size, proliferation, and polarization[58].Runx2mutation results in downregulated expression ofShhin the dental epithelium[59]. It has been shown thatRunxgene and its binding protein core binding factor β gene (Cbfb) modulate the continuous proliferation and differentiation of DESCs by activating FGF signaling loops and maintaining the expression ofShhmRNA[60]. The BMP–Smad4 signaling cascade inhibits the activity of Shh–Gli1 signaling to maintainSox2+DESCs in the CL region of mouse molars. Conversely, loss ofSmad4prolongs maintenance of the CL and affects cell expansion and differentiation[61].Ptch1andPtch2are binding receptors of Hh ligands and have distinct functional roles.Ptch1transduces Hh signaling to maintainSox2+stem cells, whereasPtch2with Desert hedgehog negatively regulates P-cadherin expression, suggesting that Hh signaling contributes to the maintenance and differentiation of DESCs simultaneously[62]. Several studies have revealed that the Notch signaling pathway is required for survival of DESCs and the formation of ameloblasts[63]. Multiple genes of this pathway are expressed in the CL, includingDelta-like 1 (Dll1)andJagged 2 (Jag2)genes encoding the Notch ligands, as well aslunatic fringe (Lfng)encoding transferase that modifies Notch receptors[63-65]. The notch responsive geneHes1is expressed in the SR. When dissected CL is cocultured with the Notch signaling inhibitorN-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-l-alanyl]-Sphenylglycine t-butyl ester (DAPT), the size of the CL is reduced because of increased apoptosis and reduced proliferation of DESCs[63].Jag2andLfnggenes are regulated by FGF and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling. Deletion ofJag2results in abnormal ameloblast differentiation[65]. The number of SI cells was increased when CLderived dental epithelial cells were cultured with Jagged 1 protein and overexpressed theNotch1internal domain. Differentiation of SI cells was inhibited whenJagged1was neutralized with specific antibody, suggesting that Notch signaling regulates SI cells, which function as a reserve progenitor pool[66]. Elimination ofNotch1+cells disrupted the repair process of injured epithelium and obstructed the regeneration of damaged dental epithelium[18]. The essential role of Hippo signaling has been suggested in coordinating the proliferation and differentiation of DESCs[67]. The effectors of the evolutionarily conserved Hippo signaling pathway, Yes-associated protein (YAP) and transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ), are expressed in TA cells[67]. It has been reported thatYAP/TAZinduce the ITG43–FAK–CDC42 signaling axis in the TA zone and activate mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling by controllingRhebexpression, maintaining TA cell proliferation and survival, and inhibiting precocious differentiation[67].

Intriguingly, there is neither expression of the Wnt-responsive geneAxin2nor expression of Wnt pathway mediators or inhibitors in the region of putative stem cells. These signs indicate that DESCs are not modulated directly by Wnt/β-catenin signaling[68]. However, Wnt/β-catenin can inhibit expression ofFgf10, a key antiapoptotic signal, to maintain a proper rate of apoptosis in DESCs[69]. AndLgr5, a Wnt signaling target gene and stem cell marker, is expressed in the putative stem cell region, the SR region underlying the OEE. TheseLgr5+cells are identified as slowcycling stem cells and a subpopulation of Sox2+DESCs[70,71]. A recent study reports thatRunx1regulates theLgr5-expressing epithelial stem cells and differentiation of ameloblast progenitors in the developing incisors. TheRunx1–Lgr5axis is partially modulated by signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) phosphorylation in the CL of growing incisors.Runx1deficiency results in downregulated expression ofLgr5andSox2and underdevelopment of the CL[70].

Apart from signaling pathways, stem cell markers, likeBmi1andSox2, are functional in the maintenance and differentiation of DESCs. The deletion ofBmi1decreased the number of stem cells, disorganized gene expression, and impaired enamel production. Knockdown ofInk4a/Arfpartially rescued Bmi1-null phenotypes.Ink4a/Arfis one critical target gene ofBmi1, which encodes the cell cycle inhibitors.Bmi1also targetsHoxgenes, which maintain the undifferentiated state of stem cells and prevent inappropriate differentiation[33]. Conditional removal ofSox2during incisor renewal resulted in the morphological change of laCL and slowed down incisor growth[72]. Conditional overexpression of lymphoid enhancer-binding factor(Lef-1)in the dental epithelium increased cell proliferation, created a new stem cell compartment in the laCL, and rescued tooth arrest resulting from deletion ofSox2[72]. These results show thatLef-1regulates maintenance of DESCs and enamel formation, but the underlying mechanism remains unresolved.

Epigenetic regulation

In addition to transcription factors, epigenetics also regulates the gene expression in mammalian development without alterations in the DNA sequence[73-75]. Epigenetic mechanisms involve DNA methylation, modification of histone tails, and gene regulation by noncoding RNAs and miRNAs[76]. Although various studies have shown the epigenetic regulation in tooth development and regeneration, there are only a few reports about the epigenetic effects in DESCs in mouse incisors.

Several studies have demonstrated that miRNAs play a role in enamel formation and the renewal and differentiation of DESCs in mouse incisors. Conditional deletion of Dicer1, an essential factor for mature miRNA formation, led to the complete loss of miRNA genesis, resulting in ectopic formation of the CL[77]. This was the result of increased proliferation of incisor epithelial stem cells and impaired differentiation of ameloblasts. Furthermore, microarray analysis unraveled that the distinct expression pattern of miRNAs in different compartments of the dental epithelium, including the laCL, lingual CL, and ameloblasts, suggests the potential role of miRNAs in the selfrenewal and differentiation of DESCs[77]. miR-200c, one of the differentially expressed miRNAs, participates in differentiation by repressingnoggin, an antagonist of BMP signaling. Noggin induces expression of E-cadherin and Amelogenin to maintain cell adhesion and promote ameloblast differentiation, respectively[74]. BMP signaling is simultaneously the upstream regulator of miRNA-200c, and a positive-feedback loop has been shown between miR-200c and BMP signaling. Another upstream regulatory pathway has also been identified in which endogenousPitx2interacts with themiR-200c/141promoter to activate miR-200c[75]. Also, miR-200a-3p is activated byPitx2and targets the BMP antagonistBmperto further regulate BMP signaling[74]. Recently, miR-1 expressed at the CL of the dental epithelium was revealed by anin situhybridization assay and its expression was inversely correlated with its target connexin (Cx) 43. Deletion of miR-1 induced DESCs to expressCx43, which regulated cell proliferation during DESC differentiation, by formation of cell–cell gap junctions and hemichannels at the plasma membrane[78].

Regulators from adjacent cells and extracellular matrix

Interactions among different cell populations and between cells and the extracellular matrix are indispensable for the homeostasis of the stem cell niche in the dental epithelium[79]. For instance, integrin β3 is required for the formation and maintenance of the CL and proliferation of DESCs. The knockdown of the CD61 gene results in a reduction of the CL size with downregulated expression ofLgr5andNotch1[80]. Ecadherin, a protein for cell–cell adhesion, regulates proliferation in TA cells and controls differentiation of DESCs[81]. Prominin-1(Prom1/CD133), an essential protein for ciliary kinetics, regulates DESCs to respond appropriately to extracellular signals. Conditional removal ofProm1impairs ciliary dynamics and the positive effects of SHH treatment, leading to the destruction of stem cell activation and homeostasis in mouse incisor tooth epithelium[82].

Finally, DESCs are regulated by other factors, such as follistatin, activin, heparinbinding molecule midkine, and heparin-binding growth-associated molecule[45,83]. Exogenous retinoic acid (RA) has negative effects on DESCsviainhibition ofFgf10. It has been demonstrated that supplementation of FGF10 in incisor cultures blocks RA’s negative effects to antagonize apoptosis and increase proliferation of DESCs in the laCL[84].

FUNCTION OF DESCS

Role of DESCs during homeostasis

The renewal and differentiation of DESCs are critical drivers of continuously growing mouse incisors[16]. The heterogeneity in DESCs has been discovered, hinting that different stem cell populations play a distinct function in mouse incisors[19]. Numerous studies have found that renewal of mouse incisors requires a balance of proliferation and differentiation of DESCs, which is controlled tightly by a complex regulated network, to maintain proper lineage ratios (Figure 3).

The renewal process of incisor enamel has been studied by constantly developing investigation methods. Continuous renewal of mouse incisors was initially observed by cutting the erupted enamel[85,86]. Sequential 3H-thymidine tracing showed the growth rate of rat incisors to be approximately 365 μm/d[13]. It was confirmed that proper incisor growth requires proliferative dividing cells in an early experiment in animals treated with mitotic arrest agents[87]. The discovery of stem cell marker candidates and genetic lineage tracing helped researchers to propose a classical model of renewal of mouse incisors. It is thought that quiescent stem cells residing in the OEE generate actively proliferating TA cells, which migrate distally and differentiate into ameloblasts that are responsible for enamel formation[16,19]. How the slowly cycling DESCs meet the daily requirement of ameloblasts has been an open question for a long time. To address this, Shariret al[18]established a novel model of mouse incisor DESCs, in which actively cycling dental epithelial progenitor cells generate both the functional ameloblasts and the surrounding nonameloblast epithelial cell populations, which are subsequently responsible for the homeostasis of mouse incisor enamel (See session ‘Updated model’ for details)[18,19]. Even though this study identified the DESCs responsible for the homeostasis, the mechanism responsible for the committed differentiation is still absent. More studies are needed to determine the underlying mechanisms by which incisor epithelial self-renewal and cell lineage distribution remain stable under physiological conditions.

Role of DESCs during injury repair

DESCs also support damaged incisor epithelium regeneration after injury (Figure 3). The number ofSox2andLgr5transcripts decreased significantly and the spherical shape of the laCL was lost after transient deletion ofSox2. SomeSox2transcripts could be detected and the laCL shape was restored after 5 d. During recovery, the percentage of EdU+cells was significantly increased in the central and proximal sections of the SR. These findings demonstrated that theSox2+DESC population could be regenerated quickly from the SR[87].

A recent study has demonstrated the migration and plasticity of DESCs during recovery. In the IEE of mouse incisors, the proliferative cells eliminated by 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) treatment were supplemented by the burgeoning proliferating cell population after 3 d. After 10 d, abnormal ameloblast organization and disorganized enamel matrix resulting from 5-FU treatment both recovered to normal. The function and dynamic changes of DESCs were further analyzed by scRNA-seq during injury repair. After cytotoxic injury, the number of cycling cells was increased with expanded expression domains ofCcnb1andBirc5, but the numbers of pre-ameloblasts and ameloblasts were significantly decreased with the distal shift. Expression ofSfrp5andCldn10was upregulated and expanded towards the proliferating regions, suggesting an increased nonameloblast population. Further study has demonstrated thatNotch1+SI cells are induced to differentiate into ameloblasts and critical for tissue recovery. These findings have shown that dental epithelium regeneration after injury is driven by recruiting more progenitors or nonmitotic pre-ameloblasts to divide, shortening the cell cycle, and delaying onset of ameloblast differentiation. Therefore, DESCs play an essential role in an appropriate and rapid response to tissue damage[18].

Potential of DESCs in tooth regeneration and tissue engineering

Whole tooth regeneration based on epithelial and mesenchymal interaction through simulating tooth development is a promising strategy for replacing lost teeth. The odontogenic potential could be retained in epithelial and mesenchymal cells isolated from the tooth germ of early development. Tooth-like structures can be producedin vitrobased on individual dental epithelial cells and mesenchymal cells from mouse embryos[88]. Bioengineered tooth germs, which are reconstructed by epithelial and mesenchymal cells, have generated functional teeth when they were placed into the alveolar socket of adult mice[89]. In addition to the mouse regenerative model, a recent study, using an allogeneic cell reassociation approach, achieved whole-tooth regeneration in minipig jawbonein situ[90].

To resolve the problem of a source of DESCs for tooth engineering, DESCs from mouse incisors have been demonstrated as an excellent tool. Besides, several studies have attempted to induce available stem cells to form dental epithelial cells. It has been reported that human tooth germ stem cells can differentiate into epithelial cell types, but not functional ameloblasts[91]. Mouse induced pluripotent stem cells (miPSCs) can differentiate into dental epithelial-like cells in serum-free culture conditions, with the addition of neurotrophin-4. These cells derived from miPSCs can express dental epithelial surface marker CD49f and ameloblast-specific markers[92]. As possible alternative sources for the human dental epithelium, human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) may be options due to their potency of multilineage differentiation[93,94]. Based on the vital role of interactions between dental epithelial and ectodermal mesenchymal cells in dental development, both hESCs and hiPSCs are induced to differentiate into epithelial-like stem cells by the HERS/ERM cell line[95]. Newlyex-vivo-formed differentiated hESCs express special epithelial stem cell markers including E-cadherin, ABCG2, Bmi-1, p63, and p75[94]. Even though rare ameloblasts, enamel, or dentin-enamel tissue were detected in this study, some progress has been made on how to obtain DESCs.

Ameloblast cell lines are indispensable for enamel formation and regeneration, because they secrete amelogenin, which is an essential constituent of enamel[96,97]. The generation of ameloblasts is still an obstacle. Although several mouse ameloblast-like cell lines, such as ALC and LS8, have been established, they do not generate enamel[98,99]. Human gingival epithelial cells have been a source of ameloblast-like cells induced by BMPs and TGF-β. It has been reported that there are 20 ameloblast-specific genes as cell surface markers, which will contribute to the isolation of human ameloblast-like cells[100].

CONCLUSION

To replace enamel defects due to caries or trauma, dentists use several artificial materials, which do not completely resemble the mechanical, physical, and esthetic features of the lost enamel[101]. Enamel regeneration has been considered as an alternative clinical strategy. Our understanding of identification, regulation, and role of DESCs has been strengthened by studying continuously growing mouse incisor models. By scRNA-seq, the heterogeneity of DESCs in the laCL has been identified and a novel mouse incisor model distinct from early evidence has been established. The updated understanding of the regulation and role of DESCs in tissue homeostasis and repair contributes to the therapeutic development of enamel engineering. Despite all this progress with DESCs in recent years, enamel regeneration still faces various challenges, which have been outlined in two recent conferences[97,102]. The difficulties include the acellular structure, high mineralization, essential epigenetic regulation during mineralization, unique migration of ameloblasts during crystal formation, and ultimate organization with prismatic and interprismatic structures of natural enamel. Several issues remain to be addressed before clinical application, such as the combination of regenerated enamel with natural teeth and the control of shape, size, color, and time. Although there are limitations in enamel tissue engineering, the exciting progress with DESCs provides researchers with novel insight into stem cellbased tooth engineering, and consequently, to pave the way for future treatments.

杂志排行

World Journal of Stem Cells的其它文章

- Acquired aplastic anemia: Is bystander insult to autologous hematopoiesis driven by immune surveillance against malignant cells?

- Glutathione metabolism is essential for self-renewal and chemoresistance of pancreatic cancer stem cells

- Effect of conditioned medium from neural stem cells on glioma progression and its protein expression profile analysis

- Immunophenotypic characteristics of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells that affect the efficacy of their use in the prevention of acute graft vs host disease

- AlCl3 exposure regulates neuronal development by modulating DNA modification

- Isolation and characterization of mesenchymal stem cells in orthopaedics and the emergence of compact bone mesenchymal stem cells as a promising surgical adjunct