Understanding cellular and molecular mechanisms of pathogenesis of diabetic tendinopathy

2020-12-22PanPanLuMinHaoChenGuangChunDaiYingJuanLiLiuShiYunFengRui

Pan-Pan Lu, Min-Hao Chen, Guang-Chun Dai, Ying-Juan Li, Liu Shi, Yun-Feng Rui

Pan-Pan Lu, Min-Hao Chen, Guang-Chun Dai, Liu Shi, Yun-Feng Rui,Department of Orthopaedics, Zhongda Hospital, School of Medicine, Southeast University, Nanjing 210009, Jiangsu Province, China

Pan-Pan Lu, Min-Hao Chen, Guang-Chun Dai, Liu Shi, Yun-Feng Rui,Orthopaedic Trauma Institute (OTI), Southeast University, Nanjing 210009, Jiangsu Province, China

Pan-Pan Lu, Min-Hao Chen, Guang-Chun Dai, Liu Shi, Yun-Feng Rui,Trauma Center, Zhongda Hospital, School of Medicine, Southeast University, Nanjing 210009, Jiangsu Province, China

Pan-Pan Lu, Min-Hao Chen, Guang-Chun Dai, Ying-Juan Li, Yun-Feng Rui,School of Medicine, Southeast University, Nanjing 210009, Jiangsu Province, China

Ying-Juan Li,Department of Geriatrics, Zhongda Hospital, School of Medicine, Southeast University, Nanjing 210009, Jiangsu Province, China

Ying-Juan Li, Liu Shi, Yun-Feng Rui,China Orthopedic Regenerative Medicine Group, Hangzhou 310000, Zhejiang Province, China

Abstract

Key Words: Tendinopathy; Diabetes; Mechanism; Tenocyte; Tendon stem/progenitor cells

INTRODUCTION

Tendons are dense and highly organized fibrous connective and collagenous tissues that are dominated by type I collagen, connect muscle to bone, and function to efficiently deliver muscle forces during musculoskeletal movement. There is an increased incidence of tendon disorders, which are characterized by impaired tendon structure, functions, and healing capacity in people with diabetes mellitus (DM)[1-4]. An epidemiological investigation demonstrated a higher prevalence of tendinopathy in patients with DM than in age- and sex-matched nondiabetic populations[5]. Tendinopathy is an important cause of chronic pain, limited range of motion (ROM) of the joints, and even tendon rupture in patients with DM[6-9].

Although some studies have focused on the structure[10,11], composition[10,12], imaging characteristics[13,14], biomechanical properties[12,15-17], and histopathological features[13,16,18]of tendons of both clinical patients and animal models of DM, clinical treatments for diabetic tendinopathy are still unsatisfactory due to a lack of understanding of the pathological changes and pathogenic mechanisms of diabetic tendinopathy[3]. The majority of practical treatments are based on current limited clinical experience rather than pathogenic changes during the course of diabetic tendinopathy. These findings emphasize the significance of understanding the pathogenic alterations in diabetic tendinopathy to explore effective therapeutic strategies.

In this review, we aim to summarize the current cellular and molecular alterations, and analyze the potential pathogenic mechanism involved in the pathogenesis of diabetic tendinopathy. The changes in biomechanical properties and histopathological features are also presented. A better understanding of the cellular and molecular pathogenesis of diabetic tendinopathy might provide new insight for the exploration and development of effective therapeutics.

CHANGES IN BIOMECHANICAL PROPERTIES IN DIABETIC TENDINOPATHY

A few studies have focused on the biomechanical properties of tendons in both human and animal models of DM. Significantly impaired biomechanical properties of diabetic Achilles tendons, such as reduced elasticity (Young’s modulus), maximum load, stress tensile load, stiffness, and toughness, have been reported[16,17,19,20]. Stiffness was also decreased in both intact tendons and healing tendons after injury in diabetic rats[21]. Evranoset al[22]found significantly reduced stiffness of the medial and distal third, but not the proximal third of diabetic tendons. This finding indicated that there might also be variations in stiffness between different regions of the tendon. However, Petrovicet al[23]showed reduced elongation and increased stiffness and hysteresis of Achilles tendons during walking in people with diabetes. This may indicate reduced storage and release of elastic energy from the tendon and a decrease in the energy saving capacity of the diabetic tendon as important factors contributing to the increased metabolic cost of walking in individuals with diabetes. Couppéet al[24]reported that regardless of hyperglycemia severity, Achilles tendon material stiffness was greater in diabetic patients than in age-matched healthy controls, but no significant differences in biomechanical properties were observed between diabetic patients with good and poor glycemic control. However, except for the decrease in the elastic modulus, de Oliveiraet al[25,26]showed increases in specific strain, maximum strain, and energy/tendon areas in diabetic tendons compared with nondiabetic tendons. Bezerraet al[27]reported increases in the elastic modulus and maximum tension of diabetic tendons. In addition to the ultimate stress and modulus in diabetic tendons at the material level, the nanoscale modulus of tendon fibrils was also significantly higher and more variable than that of nondiabetic tendons[28]. The glycated Achilles tendon showed significant increases in maximum load, Young’s modulus of elasticity, energy to yield, and toughness[29]. Diabetic flexor digitorum longus (FDL) tendons had significantly decreased ROM and a reduced maximum load at failure but increased stiffness[30]. Ackermanet al[31]also showed reduced yield load and energy to maximum force in diabetic FDL tendons, while stiffness was not altered. Although diabetes did not alter the mechanical properties of uninjured FDL tendons, the maximum force, work to maximum force, and stiffness of diabetic tendons were significantly decreased during injured tendon healing[32]. Significantly reduced stiffness at the insertion site was shown in diabetic supraspinatus, Achilles, and patellar tendons, and the modulus at the insertion site of the diabetic Achilles tendon was also decreased, but no significant difference in stiffness or modulus of mid-substance was observed in any tendon[33]. The tendon-bone complex of the supraspinatus tendon in diabetic rats also showed decreased mean load-to-failure and stiffness, impairing tendon bone healing[34]. The diabetic patellar tendon had significantly decreased stiffness with a reduced Young’s modulus[15]. However, Thomaset al[35]showed that hyperglycemia did not alter mechanics (stiffness and modulus) at either insertion site or midsubstance of the supraspinatus tendon, while some studies showed no significant changes in biomechanical properties between diabetic and nondiabetic tendons[12,36].

Based on these findings, the parameters of some biomechanical properties may be inconsistent among these studies due to different species used for models and tendon sources,in vivoandin vitromechanical measurements, various measurement methods and assessment protocols, the duration of DM and hyperglycemia severity, and other accompanying chronic complications associated with diabetes. In addition, biomechanical tests on complete tendon specimens may provide more valuable and accurate data on the biomechanical properties of the specimens than analysis of tendon segments, which might also lead to differences in measurement results. However, although there are few disagreements on the mechanical changes, the majority of studies revealed inferior biomechanical properties of diabetic tendons in human and animal models and during the healing of injured tendons. The main findings are summarized in Table 1. These impaired biomechanical properties may lead to limited ROM of the affected joints and increased susceptibility to tendon injury, reinjury, and even rupture in patients with DM.

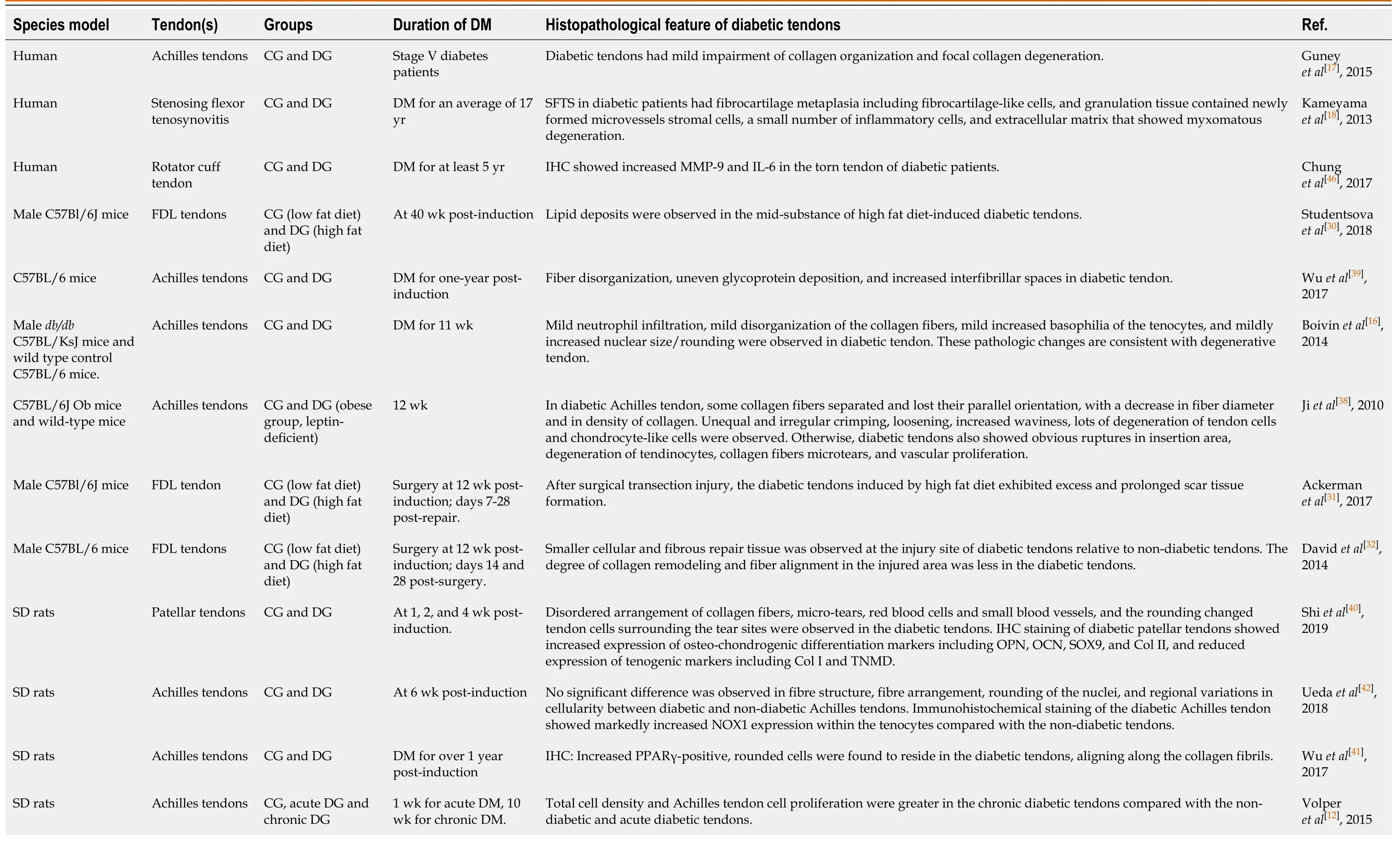

HISTOPATHOLOGICAL ALTERATIONS IN DIABETIC TENDINOPATHY

Compared with healthy tendons, diabetic tendons appear yellowish, fragile, and atrophied[15,34]. The thickness of the Achilles tendon in a diabetic rat model was significantly increased[37]. Histopathological changes were also observed in diabetic tendons. In diabetic Achilles tendons, some collagen fibers were separated and lost their parallel orientation, with a decrease in fiber diameter and collagen density, and unequal and irregular crimping, loosening, increased waviness, and degeneration of tendon cells and chondrocyte-like cells were observed; otherwise, diabetic tendons also exhibited obvious ruptures in the insertion area, degeneration of tenocytes, collagen fiber microtears, and vascular proliferation[38]. The density of fibrocytes and total cellularity, blood vessels, and mast cells were significantly increased in diabetic tendons compared with nondiabetic tendons; immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of diabetic tendons showed an increase in the density of collagen I (Col I), which was associated with disorganized fibers and the expression of vascular endothelial growthfactor (VEGF) and NF-κB, which might play roles in these vascular changes[37]. Compared with those of nondiabetic and acute diabetic tendons, total cell density and cell proliferation were increased in chronic diabetic tendons[12]. However, Thomaset al[35]showed that although cell density at the insertion site of hyperglycemic supraspinatus tendons was not altered, nor was cell shape at the insertion and midsubstance, hyperglycemic tendons had a higher cell density at the mid-substance than those of the normal hyperglycemic groups. The increase in cell density may indicate an increase in the metabolic activity of the tendon. There were also increased levels of interleukin (IL) 1-β and advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) localized to the insertion and mid-substance of hyperglycemic tendons, indicating increased AGEs and chronic inflammatory responses induced by hyperglycemia. In addition, mild neutrophil infiltration was also observed in diabetic tendons[16]. Prolonged exposure to inflammatory conditions may have a negative effect on the biomechanical properties of diabetic tendons. Significant fiber disorganization, as well as increased interfibrillar spaces, were observed in diabetic tendons[16,17,38,39]. Focal collagen degeneration[17], uneven glycoprotein deposition[39], lipid deposits[30], and increased nuclear size/rounding[16]were observed in diabetic tendons, which was consistent with degenerative tendons. Our previous work[40]demonstrated microtears, red blood cells,

small blood vessels, and changes in the rounding of tendon cells surrounding the tear sites in diabetic tendons, and IHC staining of diabetic patellar tendons showed increased expression of osteochondrogenic differentiation markers, including osteopontin (OPN), osteocalcin (OCN), Sox9, and Col II, and reduced expression of tenogenic markers, including Col I and tenomodulin (Tnmd). In addition, Wuet al[41]reported increased peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ)-positive, rounded cells residing in diabetic tendons, which were aligned along the collagen fibrils. Phenotypic variations in tendon cells may accelerate the degeneration of diabetic tendons, deteriorating the biomechanical properties of the tendons. Additionally, stenosing flexor tenosynovitis in diabetic patients was characterized by fibrocartilage metaplasia, including the presence of fibrocartilage-like cells, and granulation tissue contained newly formed microvessels, stromal cells, a small number of inflammatory cells, and the extracellular matrix (ECM) that exhibited myxomatous degeneration[18]. However, Ahmedet al[21]reported that diabetic tendons exhibited slightly smaller transverse areas than normal tendons, but showed no apparent alterations in the structural organization of collagen fibers. Uedaet al[42]showed that no significant difference was observed in fiber structure, fiber arrangement, rounding of the nuclei, or regional variations in cellularity between diabetic and nondiabetic Achilles tendons, but IHC staining of diabetic tendons demonstrated markedly increased NADPH oxidase (NOX) 1 expression within tenocytes compared with those of nondiabetic tendons, activating the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and resulting in tendon tissue damage.

Table 1 Biomechanical property changes of diabetic tendinopathy

FDL: Flexor digitorum longus; CG: Control group; DG: Diabetes group; DM: Diabetes mellitus; SD: Sprague-Dawley; ZDSD: Zucker diabetic SD; GK: Goto-Kakizaki.

The repair and regenerative capacity of diabetic tendons is compromised during the healing process after injury. Fibroblast proliferation[43,44], vascularity[21,44,45], and collagen levels[36,44]were reduced in injured diabetic tendons during healing. Egemenet al[43]showed that although similar collagen deposition and vessel proliferation were observed in both injured diabetic and nondiabetic tendons during healing, lymphocyte infiltration and osteochondroid metaplasia of some tenocytes were observed in the injured diabetic tendons. Diabetic tendons displayed a significant increase in inflammation and significantly decreased fibrosis compared with nondiabetic tendons, resulting in the delayed healing of tenotomized Achilles tendons[20]. Furthermore, after rupture, diabetic tendons had reduced reparative activities, as illustrated by a much smaller transverse area, poor structural organization with fewer longitudinally oriented collagen fibers along the functional loading axis, and decreased vascularity than injured nondiabetic tendons. Most fibers were yellowish and arranged irregularly, indicating ruptured Col I structures. IHC staining showed that reduced expression of Col I, Col III, and biglycan (Bgn) and weak VEGF, thymosin β (Tβ)-4, transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFβ1), and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) immunoreactivity were observed, and strong cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), hypoxiainducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and IL-1β expression at the injured site and increased matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-13 staining were observed around blood vessels and cells in the callus in healing diabetic tendons compared with injured nondiabetic tendons[21,45]. Additionally, MMP-9 and IL-6 Levels were also increased in the torn tendons of diabetic patients[46]. These findings indicate that increased inflammation, reduced ECM deposition, and accelerated degradation are involved in the development and progression of diabetic tendinopathy. After surgical transection associated injury, diabetic tendons induced by a high-fat diet exhibited excessive and prolonged scar tissue formation and fibrotic tendon healing, resulting in compromised biomechanical properties[31]. Smaller cellular and fibrous repair tissue were also observed at the injury site in diabetic tendons than in nondiabetic tendons, while the degree of collagen remodeling and fiber alignment in the injured area was reduced in the diabetic tendons, which was consistent with compromised biomechanical properties and was associated with decreased repair tissue size and cellularity[32].

In summary, diabetic tendons exhibit degenerative and injured features, which may be accelerated by diabetic conditions, inflammation, AGEs accumulation, and oxidative stress. The healing process of diabetic tendons after injury is also delayed and compromised, indicating the impaired repair and regenerative abilities of diabetic tendons. The main findings are summarized in Table 2. These histopathological changes in both intact and healing diabetic tendons after injury may account for the reduced biomechanical properties observed, which ultimately lead to increased risk of tendon injury and even rupture.

Table 2 Histopathological features of diabetic tendinopathy

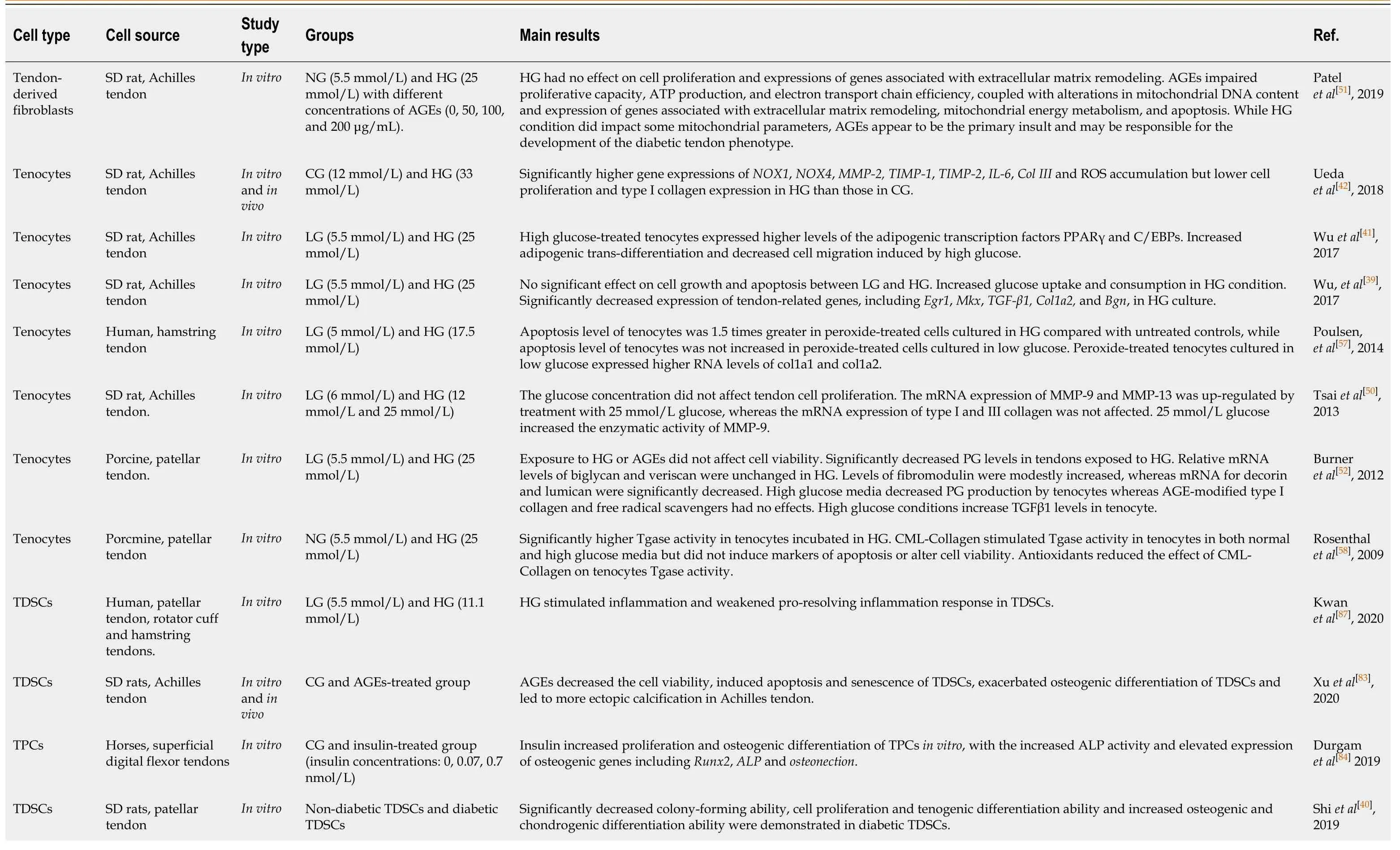

CYTOLOGICAL AND MOLECULAR ALTERATIONS IN TENOCYTES

Tenocytes are the primary cellular components of tendons and are important for maintaining tendon tissue function, mechanics, homeostasis, and capacity to remodel the ECM by generating collagen and repairing proteins and matrix proteoglycans (PGs)[47-49]. In recent years, some studies have focused on the alterations in tenocytes in diabetic tendinopathy. The main findings are summarized in Table 3. Someresearchers have shown that the proliferation of tenocytes is significantly decreased[42]and that cell migration, a crucial tenocyte function, is retarded under high glucose conditions[41]. Therefore, hyperglycemia might inhibit the ability of cells to repair damaged or degenerated tendons. In contrast, it was reported that tenocyte proliferation[50,51], viability[52], and apoptosis[39]were not affected by high glucose, and that tenocytes had increased glucose uptake and consumption in high glucose conditions in which insulin further elevated glucose consumption but did not affect either glucose uptake or expression of glucose transporter (Glut) 4, an insulin-sensitive glucose transporter[39]. This indicates that tenocytes do not rely on Glut 4 for glucose uptake. However, Wuet al[39]demonstrated that the expression of Glut 1 was approximately 15 thousand times higher than that of Glut 4, suggesting that tenocytes mainly relied on Glut 1, which is the transporter responsible for basal glucose uptake, rather than Glut 4. Therefore, due to the excessive cellular glucose overload and pronounced toxic side effects of glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation[53], tenocytes may suffer from adverse effects associated with hyperglycemia.

Table 3 Cellular and molecular alterations in tenocytes and tendon stem/progenitor cells

SD: Sprague-Dawley; NG: Normal glucose; LG: Low glucose; HG: High glucose; AGEs: Advanced glycation end-products; CG: Control glucose; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; PPARγ: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ; Egr1: Early growth response factor 1; Mkx: Mohawk; TGF-β1: Transforming growth factor beta 1; Bgn: Biglycan; PG: Proteoglycans; Tgase: Transglutaminase; CML: Carboxymethyl-lysine; TDSCs: Tendon derived stem cells; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; Runx2: Runt-related transcription factor 2; NOX: NADPH oxidase; TPCs: Tendon progenitor cells; MMP: Matrix metalloproteinase; IL-6: Interleukin-6; TIMP: Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases; Col III: Collagen III.

The expression of tendon-related genes and matrix metabolism in tenocytes are essential for maintaining homeostasis and the physiological functions of tendons. PGs are significant components and regulators of tendon structure and play key roles in tendon biomechanics and function[52,54,55]. However, Burneret al[52]reported that high glucose conditions but not N-carboxymethyl-lysine (CML)-collagen, a receptor for AGEs (RAGE)-activating AGE-modified collagen, reduced PG levels in both tendons and primary tenocytes with variations in mRNA expression of PG protein backbones, including unchanged levels of Bgn and versican, increased fibromodulin, and decreased decorin and lumican, and these effects were not reversed by inhibiting free radicals. In diabetic rat models, the transcription of tendon-related genes, such asCol1a1,Col3a1,scleraxis(Scx), andTnmd, were lower in acute and chronic diabetic tendons than in nondiabetic tendons[56]. In addition, the mRNA expression of Col I in tenocytes incubated in high glucose conditions was significantly lower than that under control glucose conditions, and the mRNA expression of Col III was significantly higher in high glucose conditions[42]. In contrast, Tsaiet al[50]reported that the mRNA expression of Col I and Col III was not altered in tenocytes treated with high glucose. Such inconsistent results may be due to the different glucose concentrations used. However, Wuet al[39]showed that the expression of tendon-related genes, includingmohawk(Mkx),early growth response factor 1(Egr1),TGFβ1,Col1a2, andBgn, was downregulated in high glucose conditions at day 14; considering that hyperinsulinemia occurs in the early phase of type 2 diabetes, the expression of Egr1, TGFβ1, and Bgn was also suppressed by insulin under high glucose conditions at day 7, and the expression of Scx and Col1a1 was suppressed by insulin at day 14. The downregulation of Mkx, Egr1, and Scx, which are crucial transcription factors associated with tendon development and repair, may alter homeostasis and impair the maintenance and remodeling of tendons by regulating the expression of downstream tendon-related genes and matrix molecule genes, which might be involved in the pathogenic mechanism of diabetic tendinopathy. Burneret al[52]detected increased TGFβ1 levels in tenocytes under high glucose conditions. TGFβ1 has important and varied effects on the metabolism of ECM components in tendons and tenocytes. TGFβ is necessary for tendon development and may participate in tendon healing, but high TGFβ levels may result in scar formation and tenocyte death[49]. These results indicate that both diabetes and insulin may result in rapid and large changes in the expression of tendon-related genes and transcription factors that are vital for ECM remodeling, maintenance, and maturation. Alterations in either PG levels or Col I and III affect the formation of collagen fibrils and the ECM, which globally impairs tendon structure, biomechanics, and tendon repair and may contribute to the pathogenesis and progression of diabetic tendinopathy.

Furthermore, Wuet al[41]also demonstrated that increased rounded, PPARγ-positive cells were observed in diabetic tendons, and high glucose conditions increased the adipogenic transdifferentiation potential of tenocytes, with elevated levels of the adipogenic transcription factors PPARγ, C/EBPα, and C/EBPβ in tenocytesin vitro. This finding may indicate a fibroblast-to-adipocyte phenotypic transition that might generate lipid deposits in diabetic tendons. The adipogenic transdifferentiation of tenocytes under high glucose conditions could cause histological, organizational, and structural changes and further impair biomechanical properties and may also be involved in the pathologic mechanism of diabetic tendinopathy.

In addition, there was a significant increase in ROS accumulation and mRNA expression of NOX1, NOX4, and IL-6 in tenocytes treated with high glucosein vitro[42]. Similarly, anin vivostudy showed that NOX1 and IL-6 were also highly expressed in the tenocytes in diabetic rats[42]. These results indicate that high glucose conditions induce oxidative stress and stimulate subsequent inflammatory processes within diabetic tendons. Moreover, anin vitrostudy by Poulsenet al[57]demonstrated that the level of apoptosis was significantly increased in primary human tenocytes exposed to oxidative stress, and apoptosis was markedly elevated in oxidative stress-treated tenocytes cultured in high glucose but not in low glucose conditions, while compared with untreated controls, oxidative stress-treated tenocytes cultured in low glucose expressed higher levels of Col1a1 and Col1a2, the gene products of which form Col I. These results suggest that a level of oxidative stress that is normally anabolic in low glucose conditions may be pathological and promotes apoptosis of tenocytes in high glucose conditions. In addition, extracellular glucose has a profound effect on the cellular response of tenocytes to oxidative stress and is a critical determinant of tenocyte fate following oxidative stress exposure.

Although CML-Collagen did not induce apoptosis or alter the viability of tenocytes, CML-Collagen stimulated transglutaminase (Tgase) activity, catalyzing the formation of highly protease-resistant intra- and inter-molecular crosslinks and mediating modifications that altered the structure and function of the ECM and contributed to tissue fibrosis by interacting with substrates, including many key ECM proteins, such as collagen, fibronectin, OPN, and microfibrillar proteins, in primary porcine tenocytes in both normal and high glucose conditions[58]. In addition, high glucose, insulin, and ROS also significantly increased Tgase activity[58]. Tgase can generate highly proteaseresistant crosslinks that alter the structure and function of affected extracellular matrices, impairing the remodeling and repair abilities of tendons and reducing the capacity of tendons to respond to injury. Tgase may also contribute to the excessive thickness, stiffness, and calcification in diabetic tendons. Additionally, Col1a1 mRNA transcript counts were significantly reduced and Col3a1 mRNA transcript counts and total ROS/superoxide production were markedly increased in tenocytes treated with AGEs[51].

The balance of ECM generation and degradation is regulated by MMPs and their inhibition by tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMPs)[59,60]. Altered levels of various types of MMPs have been detected in chronic tendon disorders and tendon healing[61-64]. Tsaiet al[50]showed that the mRNA expression of MMP-9 and MMP-13, as well as the enzymatic activity of MMP-9, was upregulated in tenocytes treated with high glucose. In addition, Uedaet al[42]reported that high glucose increased the mRNA expression of MMP-2, as well as the expression of TIMP-1 and TIMP-2. Patelet al[56]showed decreased transcription of MMP-2 and TIMP-1 in acute and chronic diabetic rat tendons. However, the MMP-9 transcript counts were significantly reduced in tenocytes treated with AGEs, but the expression of MMP-2 was increased[51]. MMPs are a family of ECM-degrading enzymes that are inhibited by MMP inhibitors called TIMPs. An imbalance between MMPs and TIMPs could result in excessive degradation of tendon ECM. Therefore, increased ECM degradation due to enhanced MMP expression, together with decreased ECM generation by tenocytes in high glucose and diabetic conditions, may weaken the mechanical properties of tendons and accelerate the development and progression of diabetic tendinopathy, predisposing individuals to tendon injury and rupture.

CYTOLOGICAL AND MOLECULAR ALTERATIONS IN TENDON STEM/PROGENITOR CELLS

In addition to tenocytes, which are traditionally considered to be the only cellular component in normal tendon tissues, a small population of tendon stem/progenitor cells (TSPCs) has also been identified in tendons from mice[65], rats[66], rabbits[67], turkeys[68], pigs[69], fetal cattles[70], and human[65,71]. These TSPCs possess stem cell characteristics including clonogenicity, proliferation, self-renewal, and multidifferentiation potential, and play significant roles in tendon repair, regeneration, and the maintenance of tendon homeostasis[72-76]. However, the characteristics and fate of TSPCs are altered under some pathological conditions, which might be involved in the pathogenesis of tendinopathy[40,77-80]. Some studies have focused on the alterations in TSPCs in diabetic tendinopathy. The main findings are summarized in Table 3.

Specific cluster differentiation markers

TSPCs derived from normal tendons are positive for Sca-1[65], Stro-1[65], cluster differentiation (CD) 44[40,65,66,68,70,71], CD90[40,65,66,68,69,71], CD105[68,69,71], and CD146[65,71]. In addition, TSPCs derived from diabetic rat tendons are also positive for CD44 and CD90. However, the expression of CD44 was markedly reduced in diabetic TSPCs compared with healthy TSPCs[40]. CD44, a cell surface glycoprotein, participates in cell growth, survival, differentiation, and motility processes[81]. Thus, the reduction in CD44 expression in diabetic TSPCs might be related to the altered cell growth, survival, multidifferentiation potential, and motility and result in a decrease in the self-regeneration and self-repair abilities of TSPCs in diabetic tendinopathy.

Cell clonogenicity and proliferation

The colony-forming ability of TSPCs from diabetic rat tendons was significantly decreased compared with that of TSPCs from healthy rat tendons[40]. Hyperglycemia is a typical clinical manifestation of DM.In vitro, high glucose could inhibit the proliferation of TSPCs from rat patellar tendons[82]. Furthermore, significantly decreased proliferation capacities of TSPCs isolated from DM rat tendons were demonstrated compared with those of TSPCs from non-DM rat tendons[40]. The accumulation of AGEs, which are oxidative derivatives resulting from diabetic hyperglycemia, is a significant feature of DM-related changes in tendinopathy[1,3]. Xuet al[83]showed that treatment with high doses of AGEs resulted in reduced proliferation of TSPCs, and pretreatment with pioglitazone significantly attenuated this effect. However, Durgamet al[84]reported that systemic hyperinsulinemia secondary to impaired insulin sensitivity could occur during early DM and that insulin could significantly increase TSPC proliferationin vitro.

Cell viability, apoptosis, and senescence

Cell apoptosis was induced when TSPCs were cultured in a high glucose environmentin vitro[82]. Additionally, Xuet al[83]reported that AGEs could decrease viability and induce apoptosis of TSPCs and significantly increase the expression of cleaved caspase-3 (C-Cas3) and cleaved caspase-9 (C-Cas9), which are key factors in apoptosis execution. These results indicate that apoptosis of TSPCs may occur in diabetic tendinopathy, and the TSPC pool may become exhausted during the progression of diabetic tendinopathy. TSPCs treated with AGEs exhibited increased expression of P53 and P21, and there was an increase in the percentage of SA-β-Gal-positive TSPCs, indicating that AGEs induced cell senescence in TSPCs[83]. However, the function of TSPCs is impaired or lost during senescence[80]. Thus, AGE-induced senescence of TSPCs may play an important role in diabetic tendinopathy. The proliferative capacity and viability of TSPCs play important roles in maintaining the physiological function of tendons. The increased apoptosis and senescence and decreased viability, together with the aforementioned reduced colony-formation and proliferative abilities, may reduce the TSPC pool and result in cellular deficits associated with tendon repair in diabetic tendinopathy.

Inflammation and the pro-resolving response

There is accumulating evidence that inflammatory cells are present, and chronic inflammation is a feature of tendinopathy[85,86], especially diabetic tendinopathy[3]. Kwanet al[87]showed that the mRNA expression of COX2 was increased in both healthy and tendinopathic TSPCs under high glucose conditions, while the upregulation of FPR1, ChemR23, and ALOX15 mRNA was significantly weakened in tendinopathic TSPCs upon IL-1β stimulation compared with that of healthy TSPCs, and the upregulation of ALOX15 mRNA was also weakened in IL-1β stimulated healthy TSPCs after preincubation in a high glucose environment. These results suggest that high glucose conditions may stimulate inflammation in tendinopathy and weaken the ability of pro-resolving response in TSPCs. However, a weakened proresolving response may lead to persistent chronic inflammation and prolonged exposure of tendon tissues to nonselective digestive enzymes associated with inflammation, resulting in excessive injury and degenerative changes in diabetic tendons.

Cell differentiation

Our previous study found that high glucose could suppress the expression of tendonrelated markers in TSPCsin vitro[82]. The inhibition of tendon-related marker expression in TSPCs suggests impaired or suppressed tenogenic differentiation abilities of TSPCs in diabetic tendons. Furthermore, our previous study[40]also demonstrated that the osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation abilities of diabetic TSPCs (dTSPCs) were significantly increased compared with those of healthy TSPCs (hTSPCs), while the tenogenic differentiation ability of dTSPCs was significantly decreased. In addition, the expression of osteochondrogenic markers such as bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), OPN, OCN, Col II, and Sox9 was also significantly increased, while the expression of the tenogenic markers Col I and Tnmd was decreased in dTSPCs. Xuet al[83]showed that AGEs exacerbated the osteogenic differentiation of TSPCs. Moreover, insulin could also increase osteogenic differentiation of TSPCsin vitro, with increased mineralized nodules, increased expression of osteogenic genesrunt-related transcription factor 2(Runx2),ALP, andosteonectin(OSN), and increased ALP bioactivity[84]. Taken together, these results suggest that the tenogenic differentiation ability of TSPCs is inhibited and that the osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation abilities of TSPCs are increased in diabetic tendons. In 2011, Ruiet al[77]first proposed the erroneous differentiation theory of TSPCs and expounded the potential roles in the pathogenesis of chronic tendinopathy. Under the pathological condition of DM, inhibited tenogenic differentiation and increased osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation, namely, the altered fate of TSPCs, are likely to affect tendon repair and facilitate the development and progression of diabetic tendinopathy. However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms of erroneous differentiation of TSPCs in diabetic tendinopathy are unclear and still need to be further illuminated.

MECHANISMS INVOLVED IN DIABETIC TENDINOPATHY

The occurrence of diabetic tendinopathy is a complicated process that is also affected by various factors, including a high glucose environment, inflammation, cytokines, hormones, enzymes, AGEs, oxidative stress, and mechanical stretch. Although epigenetic, cellular, and molecular alterations have been observed and detected in diabetic tendinopathy, the underlying mechanisms have yet to be uncovered. Based on recent progress in the cellular and molecular alterations and pathways involved in diabetic tendinopathy, the mechanisms are summarized and listed below.

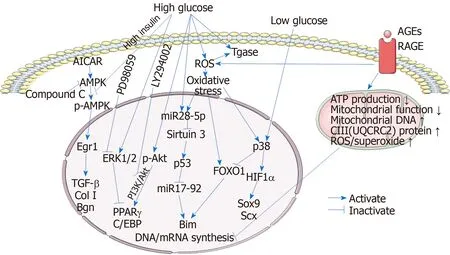

Glucose consumption in cells exposed to high glucose conditions tends to be increased and thus inactivates AMPK signal[88,89]. Wuet al[39]demonstrated that glucose uptake and consumption by tenocytes were markedly increased under high glucose conditions, and insulin further increased the glucose consumption of tenocytes under high glucose conditions, although the expression of glucose transporters was unaffected. Additionally, the expression of p-AMPKα, which is a transcriptional regulator, was dramatically downregulated in high glucose conditions, and insulin also further reduced p-AMPKα expression in the high glucose condition to some extent, indicating that increased glucose consumption in tenocytes in high glucose conditions resulted in inactivation of AMPK signaling. In addition, the mRNA expression of Egr1, a crucial transcription factor associated with tendon development and repair, was also significantly decreased in tenocytes under high glucose conditions. Furthermore, inhibiting AMPK signaling in tenocytes with the AMPK inhibitor compound C under low glucose conditions, markedly suppressed the protein expression of p-AMPKα and the mRNA expression of Egr1. Knockdown of Egr1 with siRNA significantly suppressed the expression of downstream target genes, including Col1a1, Col1a2, TGFβ1, and Bgn, and the expression of the transcription factors Scx and Mkx, suggesting that knockdown of Egr1 downregulated tendon-related gene expression. However, activation of AMPK with AICAR, an AMPK activator, under high glucose conditions could increase Egr1 expression and alleviate these changes. These results indicate that the expression of tendon-related genes in tenocytes under high glucose conditions was downregulated by inactivation of the AMPK/Egr1 signaling pathway. Previous studies have shown that knockout of Egr1 in mice attenuates tendon mechanical strength, increases interfibrillar spaces, and suppresses the tendon-related gene expression[90,91]. Thus, high glucose alters tendon homeostasis through downregulation of the AMPK/Egr1 signaling pathway and the expression of downstream tendon-related genes in tenocytes, which may be involved in the pathological mechanism of diabetic tendinopathy. In addition, Wuet al[41]also showed that high glucose elevated the mRNA expression of the adipogenic transcription factors PPARγ, C/EBPα, and C/EBPβ in tenocytes and augmented the adipogenic transdifferentiation potential of tenocytes. The protein expression of p-Akt was significantly increased, while the protein expression of p-ERK1/2 was slightly increased in tenocytes under high glucose conditions. Inhibition of PI3K/Akt signaling with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 significantly suppressed the expression of the downstream adipogenic genes PPARγ, C/EBPα, and C/EBPβ. Inhibition of ERK1/2 signaling with the inhibitor PD98059 markedly upregulated the mRNA expression of PPARγ but downregulated the mRNA expression of C/EBPα. These results indicated that activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway may play an essential role in maintaining adipogenic factor expression and promoting fibroblast-to-adipocyte phenotypic changes, whereas the activation of ERK signaling downregulates PPARγ expression, highlighting the possible pathological mechanisms of diabetic tendinopathy. Intriguingly, mechanical stretch significantly induced the phosphorylation of ERK while simultaneously repressing that of Akt in tenocytes, indicating the activation of ERK and the concomitant inactivation of Akt. In addition, the mRNA expression of PPARγ andC/EBPβ, as well as the adipogenic differentiation, was markedly reduced after tenocytes were treated with mechanical stretch[41]. These findings not only suggest the activation of ERK1/2 and PI3K/Akt signaling in tenocytes cultured in high glucose conditions but also provide new therapeutic strategies for diabetic tendinopathy. Uedaet al[42]measured ROS accumulation in tenocytes under high glucose conditions and found upregulation of NOX1 and NOX4 expression. Oxidative stress was triggered by ROS in high glucose conditions[92]. Poulsenet al[57]demonstrated that oxidative stress enhanced the tenocyte phenotype and characteristics in low glucose conditions, whereas, in high glucose conditions, tenocyte apoptosis was induced. Oxidative stress upregulated the expression of both FOXO1 and HIF1α in tenocytes. Under high glucose conditions, the level of miR28-5p was also upregulated, especially in oxidative stress-treated tenocytes. miR28-5p directly inhibited the expression of the p53 deacetylase sirtuin 3, resulting in an increase in acetylated p53. p53 inhibited the expression of miR17-92, which is a cluster of miRNAs including the Bim repressor miR17-5p, repressing the degradation of the proapoptotic protein Bim. Moreover, FOXO1 promoted the transcription ofBim, the gene product of which was a proapoptotic protein. Inhibition of Bim degradation and upregulation of Bim transcription synergistically resulted in an increase in Bim, facilitating tenocyte apoptosis. However, under low glucose conditions, the miR28-5p-sirt3-p53 pathway was not stimulated. Instead, p38 MAPK was activated and acted on both FOXO1 and HIF1α, resulting in the inhibition of FOXO1 transcriptional activity and activation of HIF1α. HIF1α enhanced the expression of the tendon-related genesSox9andScx, two genes whose products are essential for tenocyte differentiation. These factors may account for the pathogenic mechanisms of diabetic tendinopathy. Rosenthalet al[58]showed that high glucose and insulin levels increased Tgase activity, and CMLcollagen, an AGE-modified protein associated with hyperglycemia, also stimulated Tgase activity in tenocytes, which could be attenuated by antioxidants. The substrates of Tgase include many key ECM proteins, such as collagen, fibronectin, OPN, and microfibrillar proteins. Tgase produces highly protease-resistant crosslinks that alter the structure and function of affected extracellular matrices. Increased production of Tgase crosslinks may impair the ability of the tendon to remodel and repair, rendering the tendon less able to respond to injury. Tgase activity may also contribute to the excessive thickness, stiffness, and calcification observed in diabetic tendinopathy. In addition, ROS could also increase Tgase activity. Patelet al[51]demonstrated that after AGEs interact with RAGE on the tenocyte membrane, a harmful effect was initiated inside the cells. AGEs could impair the function of tenocytes by reducing ATP production, basal respiration, electron transport efficiency, and coupling efficiency, decreasing transcript counts of mitochondrial complexes, increasing mitochondrial DNA levels and complex III (UQCRC2) protein levels, and further affecting nucleus DNA synthesis with reducedCol1a1mRNA expression and increasedMMP2mRNA expression. In addition, mitochondrial and total ROS/superoxide production were also markedly increased in tenocytes that were treated with AGEs. Although high glucose conditions also affected some parameters representing mitochondrial functions, AGEs appeared to be the primary insult. Thus, AGEs, together with high glucose, ultimately altered mitochondrial energy metabolism, reduced the proliferative capacity, restricted the biosynthesis of tendon ECM, and stimulated the degradation of ECM, contributing to the development and degenerative process of diabetic tendinopathy. The potential mechanisms associated with tenocytes during the progression of diabetic tendinopathy are summarized in Figure 1.

Our previous study[82]showed that high glucose could suppress proliferation, induce apoptosis, and inhibit the tenogenic differentiation ability of TSPCs, with decreased mRNA expression of the tendon-related genesScxandCol1a1and protein expression of Tnmd and Col I. In addition to the decreased proliferative and clonogenicity abilities of diabetic TSPCs, it was also demonstrated that the osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation abilities of diabetic TSPCs were significantly stimulated, with increased expression of osteochondrogenic markers, including BMP2, ALP, OPN, OCN, Col II, and SOX9, while the tenogenic differentiation ability was remarkably suppressed, with decreased expression of the tenogenic markers Col I and Tnmd in dTSPCs[40]. The depleted population and erroneous differentiation of TSPCs might account for the pathological alterations in diabetic tendons and severely affect the tendon generation and repair potential, which may be involved in the pathogenesis of diabetic tendinopathy. However, the underlying molecular mechanism of the erroneous differentiation of TSPCs in diabetic tendons has not yet been elucidated, and further research is needed. Insulin is a conventional medicine that is used in the clinical management of DM, and systemic hyperinsulinemia secondary to impaired insulin sensitivity can occur during early DM. Durgamet al[84]demonstrated that insulin increased the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of TSPCsin vitroand increased ALP activity and the mRNA expression of osteogenic genes, includingRunx2, ALP,andOSN. In addition, the mRNA expression of IGF-I receptor was upregulated during insulin-induced osteogenic differentiation of TSPCs, and inhibition of the IGF-I receptor could reduce the insulin-induced osteogenic differentiation of TSPCs, with decreased osteogenic gene expression. These results suggest that insulin might interact with the IGF-I receptor to promote the osteogenic differentiation of TSPCs. However, the specific mechanisms involved in the insulinmediated proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of TSPCs were not further investigated. The accumulation of AGEs, which are oxidative derivatives resulting from diabetic hyperglycemia, is a feature of DM-related changes in tendinopathy. Xuet al[83]showed that AGEs decreased cell viability and induced apoptosis of TSPCs and increased the expression of C-Cas3 and C-Cas9, suggesting an increase in TSPC apoptosis induced by AGEs. In addition, AGEs increased the ratio of LC3B/LC3A and decreased P62 expression, indicating that AGEs could induce autophagy. Pharmacological activation of autophagy with rapamycin (an autophagy agonist) could decrease C-Cas3 and C-Cas9, and inhibition of autophagy with 3-MA (an autophagy antagonist) had the opposite effect, indicating that autophagy played a protective role against AGE-induced apoptosis. Pioglitazone could decrease AGEinduced apoptosis in TSPCs by activating the AMPK/mTOR pathway to stimulate autophagy. In addition, AGEs also induced TSPC senescence, with elevated expression of P53 and P21, which was defined as limited regenerative potential, decreased selfrenewal capacity, and impaired tenogenic differentiation capacity of TSPCs, enhanced osteogenic differentiation of TSPCs, and ectopic ossification, and pioglitazone could reverse these effects. These results not only reveal the pathological mechanisms of diabetic tendinopathy but also provide a new potential treatment strategy. Kwanet al[87]showed that high glucose conditions stimulated an inflammatory response and increased COX2 in both healthy and tendinopathic TSPCs; high glucose also weakened the pro-resolving responses, with decreased expression of FPR1, ChemR23, and ALOX15 in tendinopathic TSPCs and ALOX15 in healthy TSPCs, which may cause persistent chronic inflammation in tendinopathic tendons and increase the risk of diabetic tendinopathy. The potential mechanisms associated with TSPCs during the progression of diabetic tendinopathy are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 1 Mechanisms involved in the tenocytes during the process of diabetic tendinopathy.

CONCLUSION

In summary, previous studies in both patients with DM and diabetic animal models have shown the compromised biomechanical properties and histopathological alterations in diabetic tendons. Suppressed expression of collagen and PGs and transdifferentiation of tenocytes in high glucose or diabetic environments could affect the formation of collagen fibrils and the ECM and alter tendon homeostasis, which may globally impair tendon structure, biomechanics, and tendon repair. In particular, the reduced proliferation, increased apoptosis, and erroneous differentiation of TSPCs indicate intrinsic cellular deficits and an altered degenerative capacity in diabetic tendons, which eventually results in deficient of tendon repair, maintenance, and remodeling. In summary, these factors, as well as the altered expression of MMPs, may synergistically contribute to the occurrence and accelerate the progression of diabetic tendinopathy. Although limited studies have been performed and the partial results regarding the alterations in tenocytes and TSPCs and the mechanisms involved are controversial, high glucose conditions, AGEs, altered inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, and hyperinsulinemia may be associated with the cellular and molecular changes in diabetic tendons. Further studies are needed to explore the underlying mechanisms of diabetic tendinopathy, particularly the cellular and molecular mechanisms associated with erroneous differentiation of TSPCs in diabetic tendons, which would have profound implications for the exploration and development of new and effective therapeutics for diabetic tendinopathy.

Figure 2 Mechanisms involved in the tendon stem/progenitor cells during the process of diabetic tendinopathy.

杂志排行

World Journal of Stem Cells的其它文章

- Acquired aplastic anemia: Is bystander insult to autologous hematopoiesis driven by immune surveillance against malignant cells?

- Glutathione metabolism is essential for self-renewal and chemoresistance of pancreatic cancer stem cells

- Effect of conditioned medium from neural stem cells on glioma progression and its protein expression profile analysis

- Immunophenotypic characteristics of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells that affect the efficacy of their use in the prevention of acute graft vs host disease

- AlCl3 exposure regulates neuronal development by modulating DNA modification

- Isolation and characterization of mesenchymal stem cells in orthopaedics and the emergence of compact bone mesenchymal stem cells as a promising surgical adjunct