滨海适应性中的空间公平倡议

2020-12-17荷兰基斯洛克曼刘京一

著:(荷兰)基斯·洛克曼 译:刘京一

0 引言

空间(不)公平问题对于理解和响应气候变化适应性的挑战至关重要。正如爱德华·苏贾(Edward Soja)指出:“从空间角度思考公平问题不仅丰富了我们的理论认识,还可以揭示新的重要洞见,将我们的实践知识拓展为更有效的行动,从而实现更广泛的公平和民主。”[1]

运用空间和视觉概念解决问题是设计师们引以为豪的能力。我们在分析、画图、修改平面和细部设计上花费了大量时间和预算。不幸的是,在该领域中,围绕公平、设计伦理和系统性种族主义的讨论却相形见绌——无论是由于项目范畴限制、预算紧缺还是重视不足[2]。随着正在发生的新冠疫情、“黑人的命也是命”(Black Lives Matter)以及“土著团结运动”(Indigenous Solidarity)等挑战的出现,设计师不得不停下来反思如何就气候变化和气候公平的双重挑战提出相应的解决方法。

作为一篇评论而非对特定研究发现的讨论,本研究的目的是制定一个行动议程,为气候变化和海平面上升(sea level rise,简称SLR)对城市三角洲区域的影响提供一种思考视角。笔者首先介绍适应性的概念、与社区适应性价值观相结合的重要性,特别是本地和原住民社区。在此基础上,关注三角洲区域的滨海洪水管理,重点强调气候变化和空间公平交叉领域的3个新兴且相互联系的问题,包括:1)滨海栖息地的挤压;2)关键基础设施;3)撤退管理。最后,为设计师如何从空间公平的视角出发并面对这些挑战提供了建议。

1 适应性

适应性的实现需要政策、法规和实践方式的改变,以减轻气候变化的危害和负面影响[3]。然而,究竟是什么造成了危害或影响,以及如何管理它们,这取决于我们看待和理解这些影响的角度,以及这些影响产生的广泛的社会政治和环境背景[4]。这样一来,适应的合理、高效和成功与否,高度依赖在民众、团体、部门和决策者心目中,什么是值得保护和/或提升的[5]。这意味着社区价值观是成功实现气候变化适应的重要依据。因此,社区的价值观和认知必须被纳入适应性解决方案。这一方式可以综合不同的价值观和视角,拓宽决策空间,并促进适应性方案更好地落实[3]。

笔者从加拿大的视角出发,重点关注本土知识、价值观和视角如何应用于适应气候变化的规划和实践。人类活动导致的气候变化与殖民主义、资本主义背后的观念、价值和实践之间有着明显的关联[6]。因此,气候变化的影响可以被理解为殖民活动的延伸,这种影响将进一步加剧社会-空间不平等,特别是对涉及诸如管辖权、土地所有权和食物保障等问题的原住民自治主权而言[7-8]。随着承认原住民权利和所有权(Aboriginal Rights & Title)以及殖民活动对教育、民生、健康和生态系统服务造成的影响所带来的挑战,原住民社区在气候变化和海平面上升的影响下尤其脆弱[9]。

另一个挑战是如何吸收地方或区域尺度上适应气候变化的本土知识、视角和偏好,特别是社会和生态系统如何架构,如何理解它们,以及通过何种方法调查[10]。造成这种挑战的原因包括:原住民的知识常被殖民体系视为非正统的知识来源,原住民在适应性规划工作中花费的时间、提供的知识得不到报酬。

此外,水陆交界地区原住民的知识和社会-生态实践有很多值得学习的地方。关于场所、实践和联系的本土知识是代代相传和长期演化的结果,建立在对于人与其他事物关系的深入细致认识的基础上[11]。同样地,这些知识为适应气候的方法提供了重要的参考,包括海水养殖、资源利用、雨水收集以及饮食习惯改变等,这里仅列举了一小部分[12]。修斯提(Housty)等宣称:“原住民在资源管理中的自发决策是推动资源监管和生物多样性保护的绝无仅有的‘引擎’(engine)。基于此,可以认为包含原住民和自然系统的长期连接的策略在实现切实的保护效果方面有巨大潜力。”[13]为了摆脱对刚性工程手段和技术性修复的依赖,本土知识以及塑造了这种人与自然微妙关系的世界观的结合十分关键。

为了有意识地解决这些问题,设计师必须审视资本主义、殖民主义、气候变化和建成环境之间的内在联系。正如兰迪·赫斯特(Randy Hester)所言:“细分的思维十分危险且低效……每个人都需要了解如何构建公平地图、权利地图以及社会生态地图。”[2]认识到对于知识的共同创造和共同管理的需求,设计师应当致力于使有关滨海适应性的本土知识和文化实践从边缘化走向核心位置[14]。这一工作应当以促进“本土化”(indigenization)过程为中心。所谓本土化,即引入本土意图、本土互动和本土过程并使之主导空间、场所和意识转变的合作过程[15]。

对于风景园林这一从根本上关注文化与环境交叉领域研究的学科而言,围绕本土化、去殖民化和替代性设计和管理模式的讨论尤为重要。马修·科姆(Matthew Kiem)提出:“‘去殖民化设计’(decolonizing design)并非一种‘新的’或另外的设计形式,而是一个政治项目,它将设计本身连同其理论,既作为一个实体,也作为一个行动的媒介。”[16]这需要对学科中的主流概念框架、表达工具以及设计策略进行批判性的审视,以确保风景园林师不再持续助长殖民化实践。更重要的是,设计介入必须确保具有社会和生态价值的资源(包括洁净的水、绿色空间、便利设施等)以及使用和获得这些资源的机会在空间分布上的公平性[13]。

下一节将更仔细地审视城市三角洲区域所面临的适应性挑战,特别在与SLR和滨海洪灾有关的方面。城市三角洲区域是世界上最复杂和多产的社会-生态系统,同时也因城镇化、农业和过度捕捞而剧烈变化[17]。这导致了地方社区居民流离失所、滨海生物多样性大量减少、污染以及海岸动态性的改变[18]。SLR将进一步加剧这些问题,并影响食物保障和人民生计、生态系统健康以及关键基础设施。在这些问题中,最不应为全球变暖负责的群体却不成比例地承受其当前和未来的影响[5]。

2 滨海洪灾适应性

城市三角洲区域面临城市持续发展与生态系统健康、重建相协调的“棘手问题”。一方面,在城市建设和关键基础设施网络发展(包括道路、港口、电信网络和水管理系统)进程中,这些区域需要持续扩张[19]。另一方面,保护沿海资产免受洪灾侵扰导致了刚性滨海防洪工程的建设,例如水坝、防波堤、突堤等,它们对滨海生态系统和沉积过程造成了负面影响。因此,原住民社区和地方政府正面临原地适应(严防死守)和容纳洪水即撤退管理之间的抉择。笔者概括滨海适应性和空间公平的交叉领域所面临的3种相互联系的挑战,包括:1)滨海栖息地的挤压;2)关键基础设施;3)撤退管理。并提出设计师在解决这些问题时可扮演的角色。

2.1 滨海栖息地的挤压

由于目前多数城市三角洲区域的海岸线都位于刚性防洪设施以内,滨海生态系统无法随海平面上升而迁移。诸如突堤和防浪堤建设以及(为了航行的)清淤等其他因素显著改变了沉积模式,进一步影响了滨海生态系统的健康。最近的研究指出,预计到2100年,美国加利福尼亚州和俄勒冈州潮间湿地将全部消失[20]。这一即将发生的栖息地减少将对大量兼具经济和文化意义的滨海物种造成巨大影响。

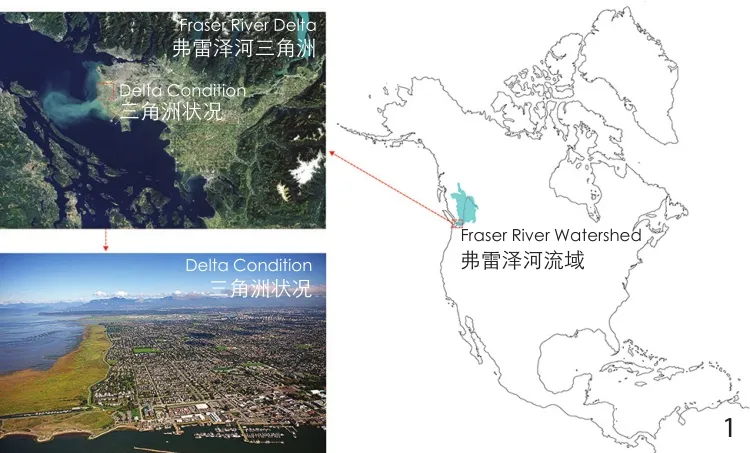

1 弗雷泽河三角洲位于弗雷泽河流域河口处The Fraser River Delta located at the mouth of the Fraser River Watershed

3 沿海撒利希第一民族与加拿大公园局共同修复罗素岛蛤蜊花园的石堤。蛤蜊花园是一种太平洋西北地区原住民所使用的古老海水养殖技术,可以理解为一种防止滨海侵蚀、提供粮食保障和提升生物多样性的NBSCoast Salish First Nations working to restore a Russell Island clam garden rock wall in collaboration with Parks Canada.Clam gardens are an ancient mariculture technique used by Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest, which can be understood as a naturebased solutions to prevent coastal erosion, provide food security, and enhance biodiversity

笔者正在进行的一项研究关注了加拿大弗雷泽河三角洲,该地区为数百万太平洋迁徙路径上的候鸟提供了重要的停留点(图1、2)。此处的河口栖息地及其食物网维系了许多重要鱼类的生存,包括每年从整个弗雷泽河流域洄游至此的数以亿计的幼龄鲑鱼[21]。该三角洲同时为白鲟(世界上最大的淡水鱼)和太平洋鲱鱼(滨海食物网的重要组成部分)提供了关键的栖息地。另外,这些鱼类与原住民的粮食主权(food sovereignty)和生活方式息息相关。与此同时,通过认识社会和生态系统间的复杂依存关系发展可能的适应方法,是解决滨海栖息地挤压问题的必要之举。这首先需要认识和可视化滨海栖息地挤压对于生物多样性、社会-生态系统和民生在十年乃至百年里的累积影响和连锁效应。

替代性滨海洪水适应方法的设计与实施也是该研究的必要部分,这些方法需要从根本上整合多种生态系统服务,包括降低洪水风险、减弱海浪以及改善滨海栖息地[22]。这种多层次、综合的方法可以归为基于自然的解决方案(nature-based solutions,简称NBS),即发展传统工程手段和生态系统相结合的混合型基础设施,重建自然与文化的关联[23]。目前,虽然越来越多的文献关注了NBS的众多挑战和优势,但仍需要更多的设计研究(design-research),以探索如何在特定的场地上运用这些方法,以及如何在特定的时空尺度上实现它们与防洪功能和生物多样性的合理平衡[24]。NBS还为结合水陆交界地带的本土知识和共治实践提供了机会。由于气候一直处于变化中(只是目前变化速度较快),因而原住民早已发展出历经时间检验的精妙的适应性技术和策略,并包含持续的试验和创新[14](图 3)。

4 弗雷泽河三角洲的饮用水供给和污水管理关键基础设施面临的洪水风险Flood risks of critical infrastructures associated with drinking water supply and waste water management in the Fraser River Delta

2.2 关键基础设施

作为人类与自然系统的衔接,基础设施网络支撑了当代城镇化进程[25]。因此,基础设施系统的故障可能带来严重的连锁效应,既会影响生态系统,也会影响区域水文、能源、食品、废弃物管理和交通服务。特别是SLR和洪水将大大挑战和危及关键基础设施(图4)。例如,“桑迪”飓风带来的洪水,严重破坏了纽约地区的交通、供暖、电信和污水网络,并导致了电网的崩溃,造成约2 100万人口数日无法使用电力[26]。

大尺度基础设施建设与殖民活动之间也有内在的联系,这些活动涉及对土地的征用和生态系统的破坏,而它们对原住民的生存至关重要[27]。历史上有关基础设施发展的思想和实践往往被包装为纯技术和工程上的创新,然而它们却具有深刻的政治意义,用以推动或维持特定的社会-经济权力博弈[28]。以北美为例,内城高速公路常被用作种族社区隔离的工具[29]。丽齐·雅莉娜(Lizzie Yarina)指出:“多数规划师认识到20世纪中叶城市更新中的误区。现在他们需要对气候适应有同样的认识。”[30]因此,关键滨海基础设施(coastal infrastructures,简称CI)的设计与重塑应该以改善本地社区和生态系统为目标,并给予弱势群体话语权。

此外,CI项目往往具有成本高昂、使用寿命长和体制惰性大等典型特征,很难实现较大改变[25]。然而考虑到未来海平面上升、城市发展进程和新技术出现的不确定性,CI适应性设计很可能更需要容纳而非阻挡洪水。这需要将静态系统转变为接纳水文动态性的系统,并为可实现洪水事件后“重建得更好”(build back better)的共治和适应性进行规划——形成可承受变化的新场所[31]。上述所有目标都关系到对于一种新的CI适应性规划设计框架的构想,这一框架试图为人类和其他物种创造场所,而不只是扶持经济增长和房地产开发的解决方案(图5)。

2.3 撤退管理

SLR对我们将来在何处生存以及如何生存有着深远影响。这不仅影响到诸如纽约、东京、孟买和大温哥华地区等主要的滨海大都市地区,同时也将影响较小的滨海社区和岛屿国家。后者在实现适应性方面的选择和资源往往极为有限,包括人口和关键基础设施重新的安置[32]。地理学家帕特里克·纳恩(Patrick Nunn)写道:“未来20~30年内,许多滨海定居点很可能……部分或全部需要重新安置。”[33]

关注“撤退管理”这一话题的空间规划、政策和公共讨论常面临困难和争议,该议题涉及社会和环境公平、身体和心理健康、法律问题、风险管理、拨款机制以及保险政策等方面[34]。目前,绝大多数文献和案例研究所关注的撤退管理都是“回应性”(reactive)的,其中涉及的重新安置可能是自愿的,也可能是非自愿的,一般源于对灾害的回应。我们需要更多关注主动性或策略性的撤退管理方式和方案。作为以“刚性”防御方式(严防死守)保护土地免受海平面上升威胁的一种替代方案,主动性撤退管理有目的地使海岸线和社区向内陆撤退。这一方式将进一步促进潮间栖息地的后撤,既可缓解滨海栖息地的挤压,又可以为洪水和侵蚀提供自然的保护(图5)。为了促进这一过程,决策时需要关注不同的空间和时间尺度,包含多个行政区域和政府层级。

尽管如此,撤退管理只是针对滨海洪水适应性的众多工具中的一种。人们仍有不少疑虑,主要围绕政府(有时是强制地)使市民和土地所有者离开其土地的合法性,以及重新安置对于低收入和边缘化社区影响的不确定性,可能损害民生、社会凝聚力和社会资本[35]。可以明确的是,社区参与对于文化敏感的(以及合理的)撤退管理方案的形成至关重要[36]。这些方案应该考虑撤退管理的各种方面,包括社会-生态权衡、场所归属感、防洪、筹款机制、法律框架以及潜在的撤退后土地利用。

5 沿河流廊道的长期策略性撤退方式的剖面渲染图Section rendering of an approach to long-term strategic retreat along a river corridor

设计师可以在新规划设计途径的开发和部署中扮演关键角色,以促进应对上述3种挑战的综合性滨海洪水适应方案的形成。制图和可视化常是各种利益相关群体创造和共享知识的开始。制图与可视化既是“过程”(分析地理空间数据、概括不同尺度的问题等)也是“结果”(创造有形的产出),通过揭示边缘化群体和非人类物种在景观中的存在,从而给予它们发声的机会[37]。例如,参与式价值地图可用作一种让参与者识别和绘制景观中有价值的场所的方法。这些价值可能涉及美学、经济、生物、生命支撑、精神、历史和文化品质等方面[38]。通过不同SLR情景的叠加,这些有价值的景观的脆弱性和影响范围便可以在空间和时间中呈现。于是,这一过程结合了本地传统知识和制图与建模等西方科学方法,形成一种面对SLR和滨海洪水的价值观导向方法(values-based approach)。价值地图为参与者共享有关重要的土地利用、实践和事件的生态知识提供了平台,而SLR模拟可以在细微之处显示海平面上升对未来的影响,起伏模型(relief-model)则便于地方社区观察和理解当地景观,并与景观产生连接。这些活动的过程与结果成为“社区的空间知识库,讨论和解读关键问题的资源”[39]。进而,对于滨海洪水适应性设计、实施和共同管理至关重要。

3 走向滨海公平

气候变化适应性不是一个可以仅通过工程手段和技术修复即可解决的技术问题,而是社会、文化和政治问题。如何表达和权衡适应性的价值观和优先级取决于我们如何动员各种社区力量的参与——特别是那些历史上缺少话语权的群体。亚历桑德拉·李(Alexandra Lee)指出:“关键问题在于重建到底对谁更好。”[40]这意味着设计师必须直面一些难题:“设计和决策包含了何种价值体系和世界观?谁的意愿被置于首位,而谁的意愿被认为缺乏合理性?与保障多数人相比,谁的人身、生计和家园被认为是次要的?”[41]在对这些问题的回答中,设计师目前仅扮演了微不足道的角色,只有很少的设计教学和实践真正参与到这些更大的社会和政治议题中[30]。

要做到这一点,我们必须彻底重新思考人类之间以及和非人类物种之间的关系,形成新的解决方案,超越狭隘的技术-经济思维驱动的水管理政策和发展模式。气候变化适应性应该这样理解,即土地、水、动物、植物与人类经历了长期的共同演进,滨海复兴在根本上依赖于增强这一系列联系的修复框架。因此,设计师需要聆听和学习社区中的当地知识和议题,同时尽力使土地所有者和利益相关者认识到设计提案的效益和利弊。

在更加强调公平的语境下,学者、实践者和设计师必须促进和推动新的设计模式,以达到空间公平与社会政治形态统一的目的[42]。这要求我们的方法和策略“不仅要满足人类主导的环境干预中的技术要求,还要维持其他的‘生命工程’目标……它们可能反映出不同的世界观和方法论”[43]。同时,也需要我们更好地认识嵌入于建成环境的设计过程与物质重建中的固有权力结构。

现在,以空间公平视角审视气候变化适应性已经迫在眉睫。

致谢:

本研究包含的讨论与行动源于对马斯魁、斯夸米什和泰斯雷尔—沃土思民族所坚守的传统领地的思考,对他们表示衷心的感谢。这一区域是了解沿海撒利希民族的最佳场所,他们的文化、历史与传统代代相传了上千年。

图片来源:

图1由基斯·洛克曼绘制,图2由格蕾丝·莫拉扎尼绘制,图3由马可·哈奇拍摄(https://twitter.com/marcohatch),图4由西莉亚·温特斯和杰西卡·黄绘制,图5由萨姆·麦克福尔绘制。

(编辑/刘玉霞)

A Call for Spatial Justice in Coastal Adaptation

Author: (NLD) Kees Lokman Translator: LIU Jingyi

0 Introduction

Issues of spatial (in)justice are fundamental to both understanding, and acting upon, climate change adaptation challenges.As argued by Edward Soja, “Thinking spatially about justice not only enriches our theoretical understanding, it can uncover significant new insights that extend our practical knowledge into more effective actions to achieve greater justice and democracy.”[1]

Designers pride themselves on being able to apply spatial and visual concepts to solve problems.We spend a large percentage of our time and budgets analyzing, drawing, and revising plans,and designing details.Unfortunately, conversations around justice, design ethics and systemic racism are less prominent in our field—whether this is due to limited project scopes, budget constraints,and lack of emphasis[2].With ongoing challenges brought to the fore by the COVID-19 pandemic,and the Black Lives Matter and Indigenous Solidarity movements, designers have to pause and reflect how to develop equitable solutions that address the twin challenge of climate change and climate justice.

Structured as a commentary rather than a discussion of specific research findings, this article aims to be agenda-setting and provide a perspective on the implications of climate change and sea level rise (SLR) on urban delta regions.I will start by introducing the concept of adaptation and the importance of integrating community adaptation values, particularly those of local and Indigenous communities.From there, I focus on coastal flood management in delta regions to highlight three emerging and interconnected issues at the intersection of climate change and spatial justice, including 1) coastal habitat squeeze;2) critical infrastructure, and; 3) managed retreat.I conclude by providing a few suggestions as to how designers can move forward to address some of the challenges through the lens of spatial justice.

1 Adaptation

Adaptation involves making adjustments to policy, regulations and practice in order to influence outcomes that alleviate harm and negative impacts of climate change[3].What constitutes harm or impact, however, and how these can be managed,highly depends upon the perspectives within these implications are framed and understood, as well as the broader socio-political and environmental context in which these impacts take place[4].As such, what is considered appropriate, effective and successful adaptation, is very much determined by what people, groups, sectors and decisionmakers deem worthy of protecting and/or enhancing[5].This means community values become an important marker for successful climate change adaptation.Hence, community values and perceptions must be built into adaptation solutions.Such an approach could mobilize different values and perspectives, broaden the decision space, and lead to greater uptake of adaptation solutions[3].

Writing from a Canadian perspective,particular emphasis should be placed on how Indigenous knowledge, values and perspectives can be taken up within climate change adaptation planning and praxis.There are clear connections between human-induced climate change and the ideologies, values and practices underpinning colonialism and capitalism[6].The impacts of climate change can therefore be conceptualized as an extension of colonization, which will further exacerbate socio-spatial inequities, specifically related to Indigenous sovereignty, e.g.jurisdiction,land rights, and food security[7-8].Due to ongoing challenges with respect to recognition of Aboriginal Rights & Title, and related impacts of colonialism on education, livelihood, health, and reliance on ecosystem services, Indigenous communities are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and sea level rise[9].

Another challenge is the inclusion of Indigenous knowledge, perspectives and priorities in climate change adaptation at the municipal or regional level, particularly concerning the way in which social and ecological system problems are framed, the way they are understood and the methodologies used for inquiry[10].This is due to several reasons, including Indigenous knowledge often not being recognized as legitimate source of knowledge by colonial institutions, and a lack of compensation for time and knowledge that Indigenous people bring to adaptation planning processes.

Moreover, much can be learned from Indigenous knowledge and social-ecological practices on the land-water interface.Indigenous knowledge about places, practices, and relations has been passed on through generations,evolved over time, and is based on a deep and nuanced understanding of human-nonhuman relationships[11].As such, they provide important markers for an array of methods related to climate adaptation, including mariculture, resource utilization, rainwater harvesting, and changing eating habits/diets, to name just a few[12].Housty et al.state that: “Indigenous self-determination in resource management represents an otherwise unavailable engine for improved resource stewardship and biodiversity conservation.Recognizing this, strategies that embrace enduring connections between indigenous people and natural systems are now seen as having great potential to achieve tangible conservation outcomes.”[13]Integration of this knowledge, and the worldviews that have produced these nuanced human-nature relationships, will be critical in order to overcome our reliance on hard engineering solutions and technological fixes.

In order to meaningfully address these issues,designers must examine the inherent connections between capitalism, colonialism, climate change,and the built environment.As argued by Randy Hester: “Segmented thinking is dangerous and a hindrance to our efficacy…Everyone should know how to make justice maps, power maps,and to map social ecologies.”[2]Recognizing the need for and co-production of knowledge and co-management, designers should aim to move Indigenous knowledge and cultural practices from the periphery to the center of coastal adaptation[14].This should centre around facilitating processes of indigenization, which can be defined as a“collaborative process of naturalizing Indigenous intent, interactions, and processes and making them evident to transform spaces, places, and hearts[15].”

Especially for the discipline of landscape architecture, which fundamentally concerns investigations at the intersection of culture and the environment, discussions surrounding indigenization, decolonization and alternative models of design and stewardship should be essential.Matthew Kiem et al.suggest:“‘decolonizing design’ is not a ‘new’ or an additional form of design but a political project that takes design as such—including its theorization—as both an object and medium of action.”[16]This requires a critical examination of dominant conceptual frameworks, representational tools, and design strategies fostered within the discipline in order to ensure the landscape architects do not continue to perpetuate colonial practices.Furthermore,designed interventions must ensure socially and ecologically valued resources (include access to clean water, green space, amenities, etc.) as well as the opportunities to use and access them, are equitably distributed across space[13].

The following section take a closer look at some of the adaptation challenges in urban delta regions, particularly with respect to sea level rise(SLR) and coastal flooding.Urban delta regions are not only among the most complex and productive social-ecological systems in the world, but they are also severely altered due to urbanization,agriculture, and over fishing[17].This has resulted in the displacement of local communities, as well as widespread loss of coastal biodiversity, pollution,and alterations of coastal dynamics[18].SLR will further exacerbate these issues, and impact food security and livelihoods, ecosystem health, and critical infrastructures.In all of this, those least responsible for causing global warming will be disproportionately affected by its ongoing and future impacts[5].

2 Coastal Flood Adaptation

Urban delta regions face the “wicked problem” of reconciling urbanization and economic growth with ecosystem health and regeneration.On the one hand, these regions aim to sustain growth by ongoing urban developments and expanding critical coastal infrastructure networks; including roads, ports, telecommunication networks, and water management systems[19].On the other hand,protecting these coastal assets from flooding has resulted in the construction of hard coastal flood protection structures, e.g., dikes, seawalls,and jetties, which has negatively impacted coastal ecosystems and sediment dynamics.As a result,Indigenous communities and local municipalities are now asked to evaluate the trade-offs between adapting in place (hold-the line), accommodating water, or managed retreat.In what follows, I will outline three interconnected challenge areas at the intersection of coastal adaptation and spatial justice, including 1) coastal habitat squeeze;2) critical infrastructure, and; 3) managed retreat,as well as the potential role designers can play in addressing these challenges.

2.1 Coastal Habitat Squeeze

With the majority of existing coastline in urban deltas fixed behind hard flood infrastructures,coastal ecosystems cannot migrate with rising sea levels.Other factors, including the construction of jetties and breakwaters as well as dredging (for navigation) and have often significantly altered sedimentation patterns, which further compromise the health of coastal ecosystems.Recent studies suggest 100% of tidal wetlands in California and Oregon are predicted to be lost by 2100[20].Such on-coming habitat loss will have profound consequences for a variety of coastal species that are of economic and cultural importance.

My ongoing research has focused on the Fraser River Delta, Canada, which provides critical stopover habitat for millions of migratory birds along the Pacific Flyway (Fig.1, 2).The estuary habitat and its food web support important fishes, including for hundreds of millions of outmigrating juvenile salmon each year that come from throughout the vast Fraser River watershed[21].The delta also provides key habitat for white sturgeon,one of the largest freshwater fish in the world, and Pacific herring, which are a foundational part of the coastal food web.Moreover, these fish are critically tied to Indigenous food sovereignty and ways of life.As such, developing potential adaptation pathways to address coastal habitat squeeze must be done in ways that acknowledge these complex interdependencies between social and ecological systems.This begins by understanding and visualizing the cumulative impacts and cascading effects of coastal habitat squeeze on biodiversity,social-ecological systems, and livelihoods from a decade-to-century scale.

It also necessitates the design and implementation of alternative coastal flood adaptation approaches that fundamentally integrate ecosystem services, including flood risk reduction, wave attenuation, and coastal habitat enhancement[22].This layered and integrated approach, which has been referred to as nature-based solutions (NBS), involves the development of hybrid infrastructures that combine traditional engineering measures with ecological systems to envision new relationships between nature and culture[23].While there is a growing body of literature that focuses more broadly on the challenges and benefits of NBS, more designresearch is needed to examine the site-specific application of these solutions in relation to their trade-offs between flood protection services and biodiversity across defined spatial and temporal scales[24].There is also an opportunity to integrate Indigenous knowledge and co-management practices on the land-water interface with NBS.Since the climate has always changed, albeit currently at faster rates, Indigenous Peoples have developed nuanced adaptation techniques and strategies that have been tried and tested over the long-term, infused with continuous experimentation and innovation[14](Fig.3).

2.2 Critical Infrastructures

As the interface between human and natural systems, infrastructures networks underpin contemporary urbanization[25].As such, a failure in an infrastructure system can have significant cascading effects and impact ecosystems as well as regional water, energy, food, waste management,and transportation services.SLR and flooding, in particular, pose significant challenges and risks to critical infrastructures (Fig.4).For example, the consequences of floods related to Hurricane Sandy in the New York area were manifold and extensive flooding disrupted transportation, heating, telecoms and sewage networks, and led to a breakdown of the electric grid that left over 21 million people without electricity for several days[26].

There are also inherent connections between the implementation of large-scale infrastructures and practices of colonization, including the expropriation of land and destruction of ecosystems essential to the livelihood of Indigenous communities[27].While often concealed as merely technological and engineered interventions,historical ideas and practices of infrastructure developments are deeply politicized in order to shift or maintain particular socio-economic power dynamics[28].In North America, for example,inner city highways have often been used as a tool for “urban renewal” to segregate racialized communities[29].Lizzie Yarina argues that: “Most planners recognize the errors of mid-century urban renewal.Now they need to have a similar awakening about climate adaptation.”[30]The design and redesign of critical coastal infrastructures (CI)should therefore aim to enhance local communities and ecosystems, and give voices to the vulnerable.

Furthermore, CI investments are typically characterized by high capital costs, lengthy service lives, and substantial institutional inertia with few opportunities for major change[25].Given the uncertainties related to future SLR, urban development trajectories, as well as the emergence of new technologies, CI adaptations may very well need to be designed to accommodate flooding rather than striving to prevent it.This involves transformation of static systems into those that embrace the dynamics of water, and planning for co-management and adaptations that “build back better” after flood events—novel places that can withstand change[31].All of this concerns imagining new planning and design frameworks for CI adaptation that seek to create places for people and more-than-humans rather than solutions that simply support economic growth and real estate developments (Fig.5).

2.3 Managed Retreat

SLR will have far-reaching consequences on where we and how we will live in the future.This will not only affect major metropolitan areas located in coastal areas, including New York,Tokyo, Mumbai and Metro Vancouver, but also smaller coastal communities and Island Nations.The latter often have limited options and resources for adaptation, including relocation of populations and critical infrastructures[32].As geographer Patrick Nunn writes, “within the next 20-30 years, it is likely that many coastal settlements…will need to be relocated, partly or wholly.”[33]

Spatial planning, policies, and public discussions around this topic of managed retreat is often difficult and controversial, involving issues of social and environmental justice, physical and mental health, legal aspects, risk management,funding mechanisms, and insurance policies[34].To date, most literature and case studies focus on analyzing reactive managed retreat, which involves both voluntary and involuntary relocation, often in response to a disaster.More research is required on developing proactive or strategic managed retreat approaches and solutions.As an alternative to maintaining “hard” defences (hold-the-line) to protect land from increasing sea levels, proactive managed retreat purposefully allows coastlines and communities to recede further inland.This, in turn, can assist the landward migration of intertidal habitat, which both mitigates coastal habitat squeeze as well as provides natural protection from flooding and erosion (Fig.5).To facilitate this,decision-making should take place across different spatial and temporal scales, involving multiple jurisdictions and levels of government.

Still, managed retreat should be seen as one of many tools in the context of coastal flood adaptation.Concerns remain around the legitimacy of governments to (sometimes forcibly) remove citizens and landowners from their properties,as well as uncertainties around post-relocation impacts of low-income and marginalized communities, including possible damage to livelihoods, social cohesion, and social capital[35].It is clear that community engagement is crucial for the development of culturally-sensitive (and appropriate) managed retreat solutions[36].These solutions should consider a whole range of aspects of managed retreat, including socio-ecological trade-offs, place attachment, flood safety,financing mechanisms, legal frameworks, and potential postretreat land uses.

Designers can play a key role in developing and deploying novel planning and design approaches to facilitate the development of integrated coastal flood adaptation solutions across all three challenge areas discussed above.Mapping and visualizing often is an essential starting point for knowledge creation and sharing across a range of stakeholder groups.As both a process (analyzing geospatial data, framing the problem across multiple scales, etc.) and product(creation of tangible outcomes), it can give a voice to marginalized groups and non-humans by literally drawing out their presence in the landscape[37].Participatory values mapping, for instance, can be used as a method to allow participants to identify and map the locations of valued places across the landscape.These values may be associated with aesthetic, economic, biological, life-sustaining,spiritual, historic, and cultural qualities, among others[38].By overlaying different SLR scenarios,vulnerabilities and impacts on these valued landscapes can be mapped across space and time.As such, it provides a method to combine local and traditional knowledge with western scientific methods of mapping and modeling to inform a values-based approach to SLR and coastal flooding.Where the creation of value maps provides a forum for participants to share ecological knowledge about important land uses, practices, and events,SLR simulations enable visualizing a fine-grain understanding of potential future implications of SLR, and the relief-model enabled the local community to see, comprehend and connect to the landscape.The processes and product created as part of these activities become “a repository of spatial knowledge of the community, and a source of discussion and interpretation around key issues.”[39]This, in turn, is essential for the design,implementation, and co-management of just coastal flood adaptation approaches.

3 Towards Coastal Justice

Climate change adaptation is not simply a technical question that can be solved with engineered measures and technological fixes.It is social, cultural, and political.How adaptation values and priorities are formulated and decided upon fundamentally depends upon ways in which we engage all communities—particularly those voices historically silences.Alexandra Lee argues that:“the key issue becomes a matter of considering for whom rebuilding can be considered better.”[40]This means designers have to engage difficult questions,including: Which value systems and world views are incorporated in design decision-making? Whose future visions are prioritized, and whose are denied legitimacy? Whose bodies, livelihoods, and homes are regarded as collateral necessary to protect the majority?[41]While designers only play a small part in answering these questions, to date, only a few design schools and design practices fundamentally engage these larger social and political issues[30].

In order to do so, we need to drastically rethink our relationships to one another and morethan human species, and develop solutions that move far beyond the narrow techno-economic considerations that have driven water management policies and developments in the past.Climate change adaptation should be driven by an understanding that land, water, animals, plants,and people have co-evolved over long periods,and revitalization of our coasts will fundamentally depend upon a restorative framework that strengthens and enhances these myriad connections.Consequently, designers need to listen and be educated by communities about local knowledge and issues as much as aiming to inform rights holders and stakeholders about the benefits and trade-offs of proposed design interventions.

Framed within a larger justice-based discourse, academics, activists, and designers must facilitate and foster the development of alternative design models that purposefully engage spatial justice and sociopolitical imaginations[42].This requires approaches and strategies that “do not only commit to meet technical requirements in human-led intervention upon the environment, but whose objective is to sustain other ‘life projects’…that might respond to different world-visions and epistemologies.”[43]This also demands increased awareness of the inherent power structures embedded in both design processes and the physical re-ordering of the built environment.

Now is the time examine climate change adaptation through the lens of spatial justice.

Acknowledgments:

I respectfully acknowledge that the discussions and activities that went into the research outlined were conceived on the unceded traditional territories of the xʷməθkwəy'əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish),and Səl'ílwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations.This region has been a place of learning for the Coast Salish Peoples, who for millennia have passed on their culture, history, and traditions from one generation to the next.

Sources of Figures:

Fig.1 drawing by Kees Lokman, Fig.2 drawing by Grace Morazzani, Fig.3© Marco Hatch (https://twitter.com/marcohatch), Fig.4 drawing by Celia Winters and Jessica Hoang, Fig.5 drawing by Sam McFaul.