Case series of three patients with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer in a single family: Three case reports and review of literature

2020-12-11MasahiroHirakawaKohichiTakadaMasanoriSatoChisaFujitaNaotakaHayasakaTakayukiNobuokaShintaroSugitaAkiIshikawaMiyakoMizukamiHiroyukiOhnumaKazuyukiMuraseKojiMiyanishiMasayoshiKobuneIchiroTakemasaTadashiHasegawaAkihiroSakuraiJun

Masahiro Hirakawa, Kohichi Takada, Masanori Sato, Chisa Fujita, Naotaka Hayasaka, Takayuki Nobuoka,Shintaro Sugita, Aki Ishikawa, Miyako Mizukami, Hiroyuki Ohnuma, Kazuyuki Murase, Koji Miyanishi,Masayoshi Kobune, Ichiro Takemasa, Tadashi Hasegawa, Akihiro Sakurai, Junji Kato

Abstract

Key Words: Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer; Signet ring cell carcinoma; CDH1; Ecadherin; Endoscopic findings; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most common neoplasm and the third most deadly cancer worldwide, with an estimated 783000 deaths per year[1]. Although most instances of GC are sporadic, approximately 1%-3% of cases arise as a result of inherited cancer syndromes[2]. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC) is an autosomal dominant cancer syndrome. The relationship between HDGC and germline mutation ofCDH1, encoding the tumor-suppressor protein E-cadherin, was first identified in New Zealand families[3]. To date, over 155 germlineCDH1mutations, of which the majority are pathogenic and a number of variants are unclassified, have been described[2]. However, the detection rate ofCDH1germline mutations in patients with HDGC is low and few cases have been reported in East Asian countries[4-10]. In the current report, we present the clinical courses of three cases with HDGC harboring a germline pathogenic variant ofCDH1, c.1679C>G, from a single family.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

Cases 1-3:Unremarkable.

History of present illness

Case 1:The proband is a 26-year-old female. She was referred to our hospital for screening esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) because her older brother died of GC 3 years ago at another hospital.

Case 2:A 51-year-old male (father of Case 1) visited our hospital for screening EGD because he had a strong family history of gastric cancer.

Case 3:As a result of taking the detailed family history, we noted that Cases 1 and 2 had several family members with GC. We suspected HDGC and performed genetic counselling for a 25-year-old younger brother of Case 1.

History of past illness

Cases 1-3:The patients had a free previous medical history.

Personal and family history

Cases 1-3 had several family members with GC. Pedigree of this family is shown in Figure 1.

Physical examination

Cases 1-3:Unremarkable.

Laboratory examinations

Cases 1-3:The serum levels of CEA and CA 19-9 were within normal limits.

Imaging examinations

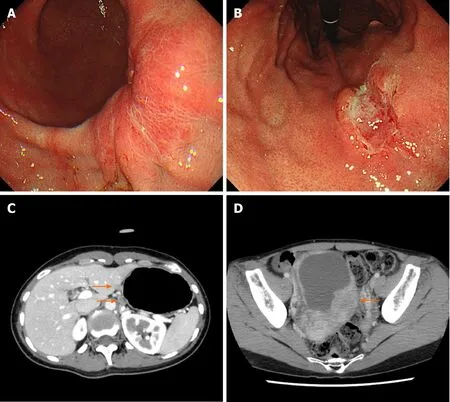

Case 1:EGD revealed advanced GC at the lower and middle body of the stomach on a background of non-atrophic gastric mucosa (Figure 2A and B). The biopsy specimens demonstrated diffuse type adenocarcinoma withoutHelicobacter pylorico-infection. Computed tomography (CT) revealed lymph node metastases along the lesser curvature of the stomach (Figure 2C).

Case 2:The patient had surveillance EGD that showed a Borrmann type 3 tumor at the fundus on a background of non-atrophic gastric mucosa (Figure 3A). A histopathological examination of the biopsy specimens revealed diffuse type adenocarcinoma withoutHelicobacter pylorico-infection. Furthermore, advanced colon cancer at the ascending colon was also detected by screening colonoscopy, although histopathological analysis indicated this was an intestinal adenocarcinoma (Figure 3B). No distant metastases were identified by CT (Figure 3C).

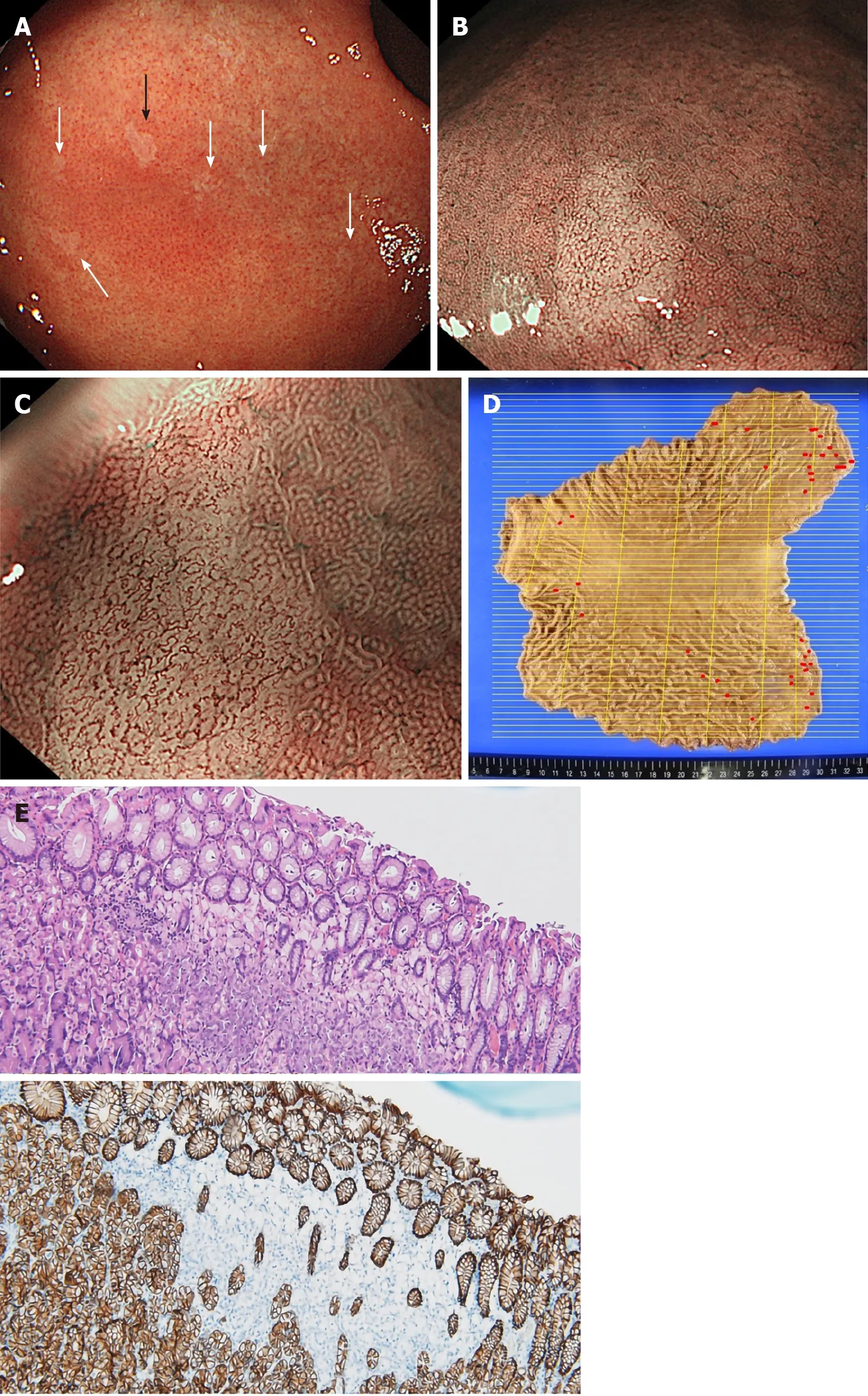

Case 3:He received surveillance EGD that detected multiple small pale lesions, mainly in the greater curvature of the stomach (Figure 4A). Narrow band imaging (NBI) without magnification showed clearly isolated whitish areas, and NBI with magnification detected “wavy” microvessels, indicating diffuse type GC, in these lesions (Figure 4B and C). We took 6 targeted biopsies from these lesions, which revealed signet ring cell carcinoma (SRCC) in all the specimens.

Further diagnostic work-up

The presence of germline CDH1 c.1679C>G (p.T560R) variant:As the three patients (Cases 1, 2 and 3) fulfilled the International Gastric Cancer Linkage Consortium (IGCLC) criteria for HDGC[2], we tested all of them for germlineCDH1mutation. This genetic testing revealed aCDH1c.1679C>G (p.T560R) variant in all three patients.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Case 1

The final diagnosis of Case 1 is HDGC.

Case 2

The final diagnosis of Case 2 is HDGC and colon cancer.

Case 3

The final diagnosis of Case 3 is HDGC.

TREATMENT

Case 1

The patient underwent total gastrectomy with D2 Lymphadenectomy (pT4aN1M0, Stage IIIA).

Case 2

The patient underwent total gastrectomy with D2 Lymphadenectomy (pT4aN3aM0, Stage IIIB) and right hemicolectomy with D3 Lymphadenectomy (pT2N0M0, Stage I).

Figure 1 Pedigree of this family. Several individuals with gastric cancer were confirmed in this family. In addition to Cases 1, 2 and 3, the CDH1 c.1679C>G variant was detected in II-4 and III-15 by further genetic analysis. GC: Gastric cancer; BC: Breast cancer; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

Case 3

Total gastrectomy with D1 Lymphadenectomy was performed (pT1N0M0, Stage IA). A total of 36 SRCC foci were observed by histological examination of the entire gastric mucosa (Figure 4D). Immunohistochemistry revealed loss of E-cadherin expression in areas corresponding to SRCC foci, which was compatible with the findings in HGDC (Figure 4E)[3].

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Case 1

Ovarian metastasis was detected by CT during the adjuvant chemotherapy (Figure 2D). Although systemic chemotherapy was continued, the patient died two years after the diagnosis.

Case 2

The GC was treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Despite treatment, the disease progressed due to peritoneal carcinomatosis during the adjuvant chemotherapy (Figure 3D), and the patient died one year after the diagnosis.

Case 3

No evidence of GC recurrence has been observed in the 3 years after diagnosis.

Relatives of cases 1, 2 and 3

Based on the result of genetic analysis, we further performed genetic counselling and genetic testing for their relatives to the extent that this was possible, and detected this variant in two of them (Figure 1). As the two p.T560R variant carriers refused prophylactic gastrectomy, we are currently continuing endoscopic surveillance for them.

DISCUSSION

Figure 2 Representative images obtained from esophagogastroduodenoscopy and computed tomography in Case 1. A and B: Advanced gastric cancer was observed at the posterior wall of the lower gastric body (A) and at the lesser curvature of the middle body (B) in esophagogastroduodenoscopy; C: Metastatic lymph nodes were detected at the lesser curvature of the proximal stomach by abdominal computed tomography (CT) (orange arrows); D: Abdominal CT showed ovarian metastasis during adjuvant chemotherapy (orange arrow).

Here we present an HDGC family with a missenseCDH1substitution variant, c.1679C>G (p.T560R). The p.T560R variant had been reported three times in patients with HDGC[11-13]. Yelskayaet al[12]reported that the p.T560R mutation created a novel 5¢ splice donor site that led to truncation of E-cadherin. Furthermore, Pena-Cousoet al[13]performed functional analyses, which revealed that the p.T560R mutation causes an abnormal pattern of E-cadherin expression in the cytoplasm, disrupts cell-cell adhesion and promotes cellular invasion. Consistent with these reports, loss of Ecadherin expression at SRCC foci was observed in Case 3. Furthermore, we observed early recurrence and rapid progression of GC after radical resection in Cases 1 and 2. E-cadherin is a member of the cadherin family and mediates calcium-dependent cellcell adhesion[14]. Reduction of E-cadherin expression promotes invasion and metastasis in various cancer types through initiation of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition[15]. Indeed, HDGC patients with germlineCDH1mutations have shorter survival times compared to those without germlineCDH1mutations[16]. On the other hand, the loss of E-cadherin may not be sufficient for the development of invasive gastric adenocarcinoma, because signet ring-like cells are observed in gastric mucosa of Ecadherin-deficient mice, but this does not lead to development of carcinomas that invade the submucosa[17]. In addition to the loss of E-cadherin, other genes, such asSmad4andp53, may play important roles in tumorigenesis and metastasis in HDGC[18].

With respect to gastric endoscopic findings, multiple small pale lesions were observed with white light imaging in Case 3 and all biopsy specimens from the pale lesions revealed SRCC. Pale lesions in HDGC patients possibly reflect microscopic foci of early SRCC, although their presence is not diagnostic for this disease[2,7,10,19]. On the other hand, Hüneburg and colleagues[20]reported that combining targeted biopsies from abnormal findings (including pale lesions) with random biopsies did not improve detection of SRCC foci inCDH1mutation-positive HDGC patients. Currently, the IGCLC guidelines for endoscopic surveillance of HDGC recommend that all endoscopically visible lesions (including pale areas) are biopsied, and after sampling of all visible lesions, five random biopsies should be taken from each of the following anatomical zones: prepyloric, antrum, transitional zone, body, fundus and cardia[18]. Nevertheless, the rate at which SRCC foci are detected inCDH1mutation carriers following endoscopy is 45%-60%, which is relatively low[19,21-23]. Further studies are needed to improve the accuracy of endoscopic diagnosis of HDGC. Additionally, we recognized the SRCC foci as clearly isolated whitish areas by NBI and observed wavy microvessels inside the lesions by magnifying NBI. NBI has not previously been validated as a method for diagnosis of patients with HDGC[19,23]. Interestingly, the NBI findings that we observed in Case 3 are similar to those previously reported in studies of early SRCC patients[24-27]. Although the detection of small intramucosal SRCC foci is not easy because most of them are covered by a normal foveolar epithelium, the endoscopic findings that we observed in Case 3 are informative for the detection of early SRCC foci inCDH1mutation-positive HDGC patients.

Figure 3 Representative images obtained from esophagogastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy and computed tomography in Case 2. A: Advanced gastric cancer was observed at the fundus in esophagogastroduodenoscopy; B: Colonoscopy showed advanced colon cancer at the ascending colon; C: Metastatic lymph nodes at the lesser curvature of the proximal stomach without distant metastasis were identified by abdominal computed tomography (CT) (orange arrow); D: Peritoneal dissemination were observed by abdominal CT during the adjuvant chemotherapy (orange arrow).

Lastly, it is well known that germlineCDH1mutations increase the lifetime risk of developing lobular breast cancer. Although we performed breast cancer screening for Case 1, no breast cancer was detected. In contrast, coexistence of colon cancer was revealed in Case 2. Currently, it is unclear whetherCDH1germline mutations also increase the risk of colorectal cancer. There are several case reports of colorectal SRCCs in germlineCDH1mutation carriers[28-31]. However, as the histopathology of colon cancer in Case 2 indicated intestinal adenocarcinoma, the relationship betweenCDH1mutation and development of colon cancer in Case 2 is not certain. Interestingly, Salahshoret al[32]reported that the colorectal cancer subtype associated with HDGC can be intestinal adenocarcinoma. Further studies are needed to clarify whether germlineCDH1mutations cause colorectal carcinogenesis.

CONCLUSION

We report an HDGC family with a missenseCDH1variant, c.1679C>G (p.T560R), where active genetics evaluation and intensive endoscopic surveillance in Case 3 resulted in early diagnosis and treatment of HDGC. HDGC has rarely been reported in East Asian countries. However, the rarity of HDGC in East Asian Countries may be related to insufficient surveillance or overlooked cases and may not reflect the actual prevalence. We therefore recommend that individuals suspected of having HDGC (e.g., fulfilling the IGCLC criteria for HDGC, existence of multiple SRCC foci) should be offered genetic counselling and mutation analysis in cooperation with cancer genetics professionals. The present report will contribute to an increased awareness of HDGC and will improve the performance of endoscopic diagnosis for early SRCC foci in HDGC patients harboring aCDH1mutation.

Figure 4 Representative images obtained from esophagogastroduodenoscopy and pathological findings in Case 3. A: Multiple small pale lesions were observed mainly at the greater curvature of the gastric body in esophagogastroduodenoscopy (white and black arrows); B: Clearly isolated whitish areas were detected by non-magnifying narrow band imaging (NBI). The image is the lesion indicated by the black arrow in (A); C: Magnifying NBI detected wavy microvessels inside the lesions; D: A gastrectomy mapping study revealed 36 signet ring cell carcinoma (SRCC) foci in the entire gastric mucosa. Red lines indicate SRCC foci; E: Hematoxylin and eosin staining (upper panel) and immunohistochemistry for E-cadherin (lower panel) of the lesion. Loss of immunoreactivity at SRCC foci was confirmed.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in lean subjects: Prognosis, outcomes and management

- Modern surgical strategies for perianal Crohn's disease

- Simultaneous colorectal and parenchymal-sparing liver resection for advanced colorectal carcinoma with synchronous liver metastases: Between conventional and mini-invasive approaches

- Estimation of visceral fat is useful for the diagnosis of significant fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- Nomograms and risk score models for predicting survival in rectal cancer patients with neoadjuvant therapy

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and gastrointestinal morbidity in a large cohort of young adults