早期云计算如同从图书馆借书

2020-08-28戴夫·格什戈恩

戴夫·格什戈恩

The idea of cloud computing, which is really just multiple people using the same computer hardware at the same time, has been around since some of the first computer systems.

Before the internet, there was ARPANet1, an experimental government-funded prototype2 for a connected communications network of computers.

But before ARPANet, there was another technology called time-sharing3. It was a glimpse of our own connected future—well before the dawn4 of the personal computer, the smartphone, or even the web.

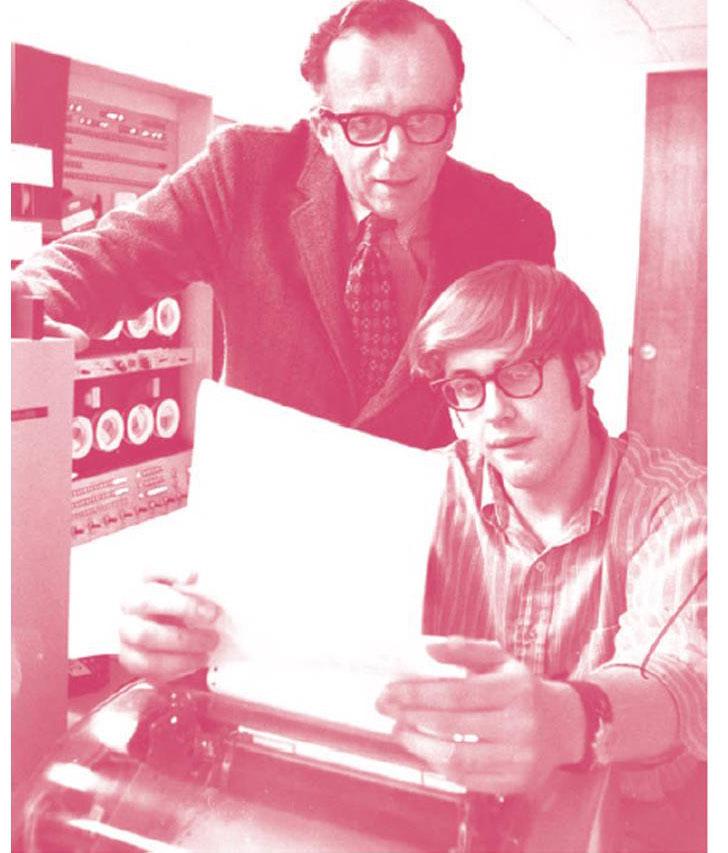

Time-sharing was a way of computing where a user would type into a typewriter-like terminal connected to a phone line. That phone line would connect to a larger computer somewhere else in the US. The code typed into the terminal would be transmitted to the larger computer, which would run the code and then send the output back through the phone lines to the user.

How time-sharing began

Through the mid-20th century, scientists worked at transforming the computer from a mechanical machine to an electronic one, shrinking the hardware from the size of a room to something that fit on a desk. But even these early, clunky5 electronic computers were still only capable of running one persons program a time, and generally were only found at universities and government research facilities. Everyone else at the research center would have to wait until the current programmer was done, and then reconfigure the computer for their use afterward. This hassle6 led to the development of a process called “time-sharing,” where computers could automatically handle a queue of codes to execute one after another.

One of the first projects to tackle7 time-sharing was MITs Project MAC8, according to 1965 MIT graduate and then Project MAC contributor Tom Van Vleck.

“Time-sharing a single computer among multiple users was proposed as a way to provide interactive computing to more than one person at a time, in order to support more people and to reduce the amount of time programmers had to wait for results,” he wrote in 2014.

This is essentially the same idea that big tech companies are using today, but the speed and scale has been exponentially9 increased. Instead of simple mathematical equations10 among a handful of researchers, billions of lines of code are being run from millions of different users on tens of thousands of servers. These servers are just high-powered11 computers, custom-built12 to work together, and still take up entire warehouses, but can accomplish many orders of magnitude13 more computing than their earlier room-sized ancestors.

The idea of time-sharing and linking computers together in the 1960s would be formative14 for decades to come. In 1968, J. C. R. Licklider15, a director at the US Department of Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), wrote a paper titled “Compu-ters as a Communications Device” that would sketch out the basis of the internet and the idea of connecting compu-ters to one another, which influenced the creation of ARPANet itself.

“It appears that the best and quickest way… to move forward the deve-lopment of interactive communities of geographically separated people—is to set up an experimental network of multiaccess computers,” he wrote.

Making money selling computer processing

In the 1960s, computers were marketed to mathematicians and scientists because of their enormous cost. But with time-sharing, which could be done from long distances over a phone line, the cost of the hardware was distributed across many customers, meaning access could be cheaper. The institutions that at first were only using computers for mathematics found that they could use computers for office automation tasks like payroll and mailings and forms and simple databases.

In the years after Lickliders paper, about 150 businesses formed in the US to provide time-sharing services, according to the Computer History Museum. Small, portable typewriters with simplistic computer chips would be rented on a monthly basis, and when plugged into a phone line, these terminals would connect to a large computer elsewhere in the country. Customers were charged for how much computing power they used.

The 1980s saw the introduction of smaller, more affordable microchips, leading to the era of the personal computer, led by the likes of Apple and IBM. Time-sharing started to feel unnecessary, as many had now machines at their offices or homes, and didnt need to call into a computer somewhere else to get their work done.

But it wasnt long before the idea of “cloud computing” sprang up16. In 1997, entrepreneur Sean OSullivan filed a trademark on the phrase “cloud computing,” according to MIT Technology Review. (The trademark is now dead.) OSullivans company was hammering out a contract with PC manufacturer Compaq17, where OSullivan would provide the software for Compaqs server hardware. The two would in turn sell that technology to burgeoning18 internet service providers like AOL, who could offer new computing services to their customers.

The first mention of the technology was scribbled19 in a daily planner in 1997, inside the offices of Compaq Computer, where a small group of technology executives was plotting the future of the Internet business and calling it “cloud computing.” Their vision was detailed and prescient20. Not only would all business software move to the Web, but what they termed “cloud computing-enabled applications” like consumer file storage would become common. Compaq predicted that enterprise software, which needed to be directly installed on users computers, would be usurped21 by cloud services distributed over the internet, what we now call “Software as a Service” or SaaS.

Thats the world we live in today. But it all started with time-sharing, and the simple idea that you could book time on someone elses computer.

自第一批計算机系统问世以来,云计算的概念就产生了。云计算,实际上就是多个人同时使用一套计算机硬件。

先于互联网出现的,还有由政府资助的计算机互联通信网络实验原型——阿帕网。

而在阿帕网之前,还有一种叫作分时的技术。这种技术让我们初步感知了网络互联的未来,后来很久才出现了个人电脑、智能手机甚或网络。

分时是一种用户使用连接电话线的打字机式终端进行输入的计算方式。电话线会连接到美国其他地方的一台大型计算机上。大型计算机在收到输入终端的代码之后,会运行代码,并通过电话线将输出内容返回给用户。

分时技术的起源

在整个20世纪中叶,科学家们都致力于将计算机从机械化转变为电子化,将硬件从房间大小缩减到桌面大小。但即便是这些笨重的早期电子计算机,一次也只能运行一个人的程序,并且通常只有大学和政府研究机构才有。研究中心的其他所有人都必须等正在使用的程序员完事了,再重新配置计算机供自己接下来使用。这种窘境促进了 “分时”处理的发展,让计算机能够自动轮流处理一列代码。

据1965年毕业于麻省理工学院的汤姆·范弗利克介绍,麻省理工学院的“数学与计算”项目是最早研究分时技术的项目之一,他当时曾参与此项目。

他于2014年写道:“提出由多名用户分时使用同一台计算机的方法,为多人同时提供交互式计算,由此支持更多人共用,并缩短程序员等候结果的时间。”

如今,大型科技公司仍在使用基本相同的概念,只是速度和规模已呈指数级增长——不再是少数几个研究人员运行简单的数学方程式,而是数万个服务器同时为数百万名用户运行数十亿行代码。这些服务器是特殊定制、可协同工作的大功率计算机,虽然体积依然大到占满整个库房,但完成运算指令的数量级比房间大小的早期计算机大得多。

1960年代的分时概念和计算机互联概念对接下来的几十年产生了深远影响。1968年,美国国防部高级研究计划局的一位负责人J. C. R.利克莱德曾经写过一篇题为“计算机作为通信设备”的论文,描绘了互联网的基本原理和计算机互联的概念,促使了阿帕网的诞生。

他写道:“看来,促使地理上分隔的人们建立互动社区的最好最快的方法是,设立一个多路存取计算机实验网络。”

计算机进入大众消费市场

1960年代,由于成本巨大,计算机只被推销给数学家和科学家。但有了分时技术之后,通过电话线远程接入,硬件成本可以由众多客户分摊,这意味着使用计算机变得更便宜了。最初只将计算机用于计算的机构发现,他们可以使用计算机完成制作工资单、发邮件、制表和建立简单数据库等自动化办公任务了。

据计算机历史博物馆记载,在利克莱德发表论文后的数年内,约有150家提供分时服务的企业于美国成立。带有简单计算机芯片的小型便携式打字机按月出租。插上电话线,这些终端就可以连接上美国其他地方的一台大型计算机。客户使用多少计算能力,就支付多少费用。

1980年代,体积更小、更便宜的微型芯片出现了,由此进入了由苹果和IBM等巨头引领的个人电脑时代。许多人在办公室或家里配备了计算机,无须再调用其他地方的计算机来完成工作,因此分时技术开始变得可有可无。

但在不久之后,“云计算”的概念就开始生根发芽。据《麻省理工学院技术评论》记载,企业家肖恩·欧苏利文于1997年用“云计算”一词注册了商标。(目前该商标已过期。)欧苏利文的公司与个人电脑制造商康柏公司签订了合同,欧苏利文为康柏的服务器硬件提供软件。两家公司继而将这项技术销售给美国在线等新兴互联网服务提供商,这些提供商向其客户提供新型计算服务。

这项技术第一次被提及是在1997年,是在康柏公司办公室的一张日程表上潦草写下的,几位技术高管规划着这项因特网业务的未来,并称其为“云计算”。他们的愿景既详实又高远。他们不仅计划将所有的商业软件转移到网上,还计划普及客户文件存储等所谓的“云计算应用程序”。康柏预测,需要直接安装在用户计算机上的企业软件将被分布在互联网上的各种云服务(现称为“软件即服务”,简称SaaS)所取代。

我们如今就身处在这样的世界。但这一切都始于分时技术,源于你可以预约使用他人计算机的这一简单概念。

(译者为“《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛获奖者)