Acceptance on colorectal cancer screening upper age limit in South Korea

2020-08-24XuanQuyLuuKyeongminLeeYunYeongLeeMinaSuhYeolKimKuiSonChoi

Xuan Quy Luu, Kyeongmin Lee, Yun Yeong Lee, Mina Suh, Yeol Kim, Kui Son Choi

Abstract

Key words: Colorectal cancer; Cancer early detection; Mass screening; Patient participation; Elderly; Patients dropouts

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common types of cancer worldwide, with the fourth highest incidence among both sexes and the third highest among men in 2018[1]. In general, CRC is more common in countries with a high Human Development Index score and in Western countries[1]. Meanwhile, screening for CRC is recognized as an effective intervention through which to reduce the numbers of new cancer cases and cancer deaths[2-5]. To reduce the burden of CRC, population-based screening programs with a variety of screening tests, such as colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, double-contrast barium enema, and fecal occult blood test (FOBT), have been adopted by many developed countries[6]: The United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends colorectal cancer screening for people aged 50 to 75 years, and for adults aged 76 to 85 years, decisions on CRC screening should reflect the patient’s overall health and their screening history[7]. According to recommendations from the European Colorectal Cancer Screening Guidelines Working Group, FOBT as a primary test in screening programs is effective in reducing mortality among people aged 45-80 years at a screening interval of 2 years; colonoscopy-based screening programs are beneficial for individuals aged 50-74 years[8]. A recently published systematic review showed that the majority of guidelines recommend an age range of 50 to 70 or 75 years as appropriate for CRC screening[9].

Although research on an appropriate age at which to stop CRC screening is limited, a few reasons for setting an upper age limit for CRC screening have been given: One is that older adults involve higher risks of complications due to treatment and screening, particularly colonoscopy, which can be invasive and requires bowel preparation[10-13]. Another is the potential for physiological harm. Parkeret al[14]indicated that a positive FOBT test results in a high level of anxiety in patients that returns to normal with negative results. In addition, with increasing age, life expectancy decreases, and this can differ with the presence of comorbidities[15]. Although there is no gold standard for deciding when to stop CRC screening, age is the most common criterion. However, some studies have shown that people are not likely to comply with age-based stoppage recommendations[16-18]. Indeed, about a half of the respondents in a study in England indicated that doctors should never use age as a criterion for deciding when to stop screening, even with a normal colonoscopy test result in previous years[16].

In South Korea, CRC is a major public health concern, as the second most commonly diagnosed cancer type in 2016, increasing in incidence with age up to 85 years[19]. The National Screening Guidelines for CRC in South Korea were developed by a multisociety expert committee in 2015. The committee systematically reviewed the selected screening guidelines and results of randomized controlled trials and considered the incidences of CRC for individual age groups and according to life expectancy. With a life expectancy of 79.9 for men and 85.7 years for women, The Korea National Cancer Center has recommended CRC screening for adults aged 45 to 80 years, as there is insufficient evidence of the benefits of CRC screening after the age of 80 years[20]. Notwithstanding, the Korea National Cancer Screening Program does currently provide biennial FOBT and either colonoscopy or double contrast barium enema as a follow-up test for CRC screening for adults aged over 50 years with no upper limited age[21].

In general, people are likely to only pay attention to the benefits of cancer screening and to neglect its risks. Most consider the benefits of cancer screening as being far greater than the risks and are unaware that any potential benefits and harms can vary with age. Although several CRC screening guidelines recommend setting an upper age, there is a lack of information on perceptions and acceptance of an upper age limit for CRC screening. Accordingly, using a national representative survey of cancer screening in South Korea, our study sought to investigate acceptance of an upper age limit for CRC screening and factors associated therewith among cancer-free individuals targeted for screening in South Korea.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study material

In this study, we used data on 4500 Koreans from the Korean National Cancer Screening Survey (KNCSS) 2017. The data resource profile of the KNCSS has been well described in the literature[21]. In brief, the KNCSS is a nationally represenative, crosssectional survey covering the five most common types of cancer, including stomach, liver, colorectal, breast, and cervical cancer. Subjects are selected by a multi-stage random sampling method that is stratified by sex, age, and residence area based on annual estimates from the National Statistical Office. The survey focuses on behavioral patterns related to cancer screening. Cancer-free men aged 40 years or over and cancer-free women aged 30 years or over are eligible for inclusion in the KNCSS. In this study, we included only men and women aged 50 years and older who were targeted for CRC screening in the Korea National Cancer Screening Program. A total of 1922 men and women were included in the final analysis. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Center, South Korea (approval number: NCC2019-0233).

Measures

Acceptance of an upper age limit for CRC screening was assessed using an informative question that first explained CRC screening recommendations, focusing on an appropriate age for CRC screening, and then asked whether screening should be stopped at an age of 80 years as recommended by the National Cancer Center of Korea. If the participant responded “no,” they were then asked to share their preference for an alternative age at which to stop CRC screening.

Using a structured questionnaire, the participants were asked about their experiences with screening for CRC. The questions included “Have you ever undergone CRC screening?” and, if so, “When did you last undergo CRC screening?” and “What tests did you receive for CRC screening?” Screening status was defined as “screened” for those who had ever undergone FOBT in the past or who ever had a colonoscopy. Otherwise, participants were considered as “non-screened.” Screened individuals were further classified into the following three groups: screened by FOBT only, colonoscopy only, or both. Socio-demographic characteristics, health status, and health-related behaviors were also examined.

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics of the study population are presented as unweighted numbers and weighted proportions. Logistic regression was applied to identify associations between acceptance of an upper age limit and CRC screening history, as well as other factors. First, univariate logistic regression models were used to examine associations for acceptance of an upper age limit with individual factors. Variables with aPvalue less than 0.05 in the univariate model were included in a multivariable regression model. A final regression model was developed with stratification according to CRC screening history. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software (version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States).

RESULTS

Overall characteristic of study population

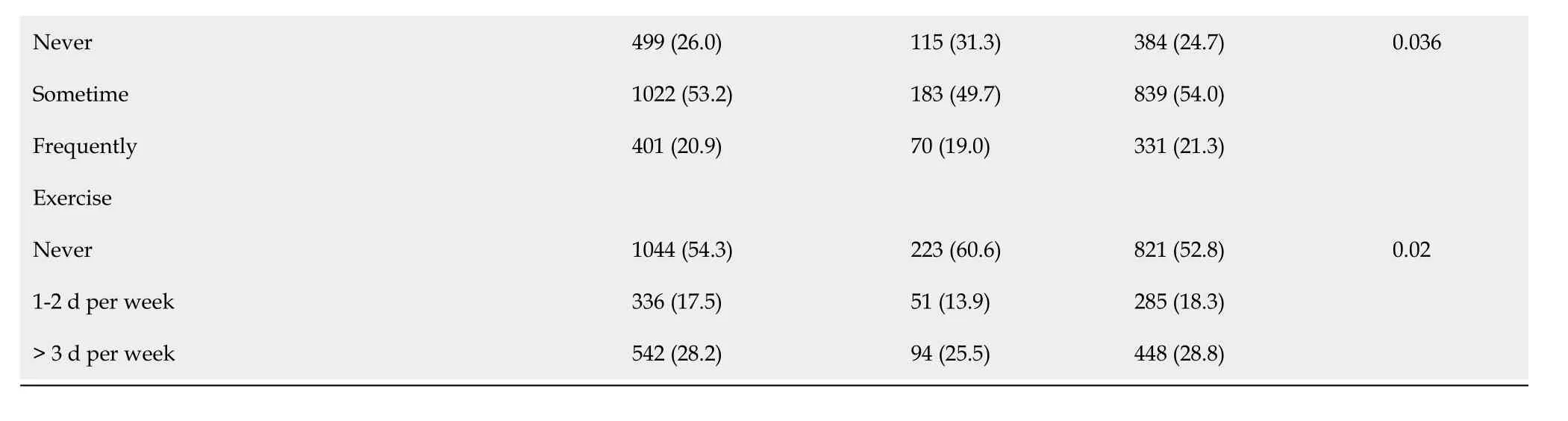

The baseline characteristics of the 1922 participants are presented in Table 1. Overall, 51.8% of the study population was female, and 53% was aged 50-59 years. The majority of the respondents had completed middle school or high school (73.9%), were married (94.7%), and had no family history of cancer (78.5%). About 26% of the participants reported having never been screened for CRC; the histories of CRC screening by FOBT only, colonoscopy only, and both were 35.8%, 15.6%, and 22.4%, respectively. Overall, 80.8% of the respondents agreed with stopping CRC screening at the age of 80 years. Individuals aged 50-59 years, men, metropolitan residents, people living with a spouse, smokers, heavy drinkers, and those who exercised regularly were more in favor of stopping CRC screening at an age of 80 years. Also, those who had never been examined for CRC or any other type of cancer and those without a family history of cancer reported higher acceptance rates for an upper age limit of 80 years. More specifically, those who had never been screened for CRC had the highest acceptance rate (91%), while those who had been examined for CRC through both FOBT and colonoscopy had the lowest acceptance rate (73%) (Figure 1). People who did disagree with an upper age limit at age 80 years reported a preferred alternative age of a mean of 89.8 years (median: 90.0).

Factors associated with acceptance on CRC screening upper limit age

In both univariate and multivariate regression models, a negative association between CRC screening history and acceptance of an upper age limit for CRC screening at 80 years was observed (Table 2). Those who had been screened for CRC through both FOBT and colonoscopy were less likely to accept the upper age limit [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 0.33, 95%CI: 0.22-0.50], compared with those who had never been screened. Similarly, participants who had ever been screened for any other type of cancer (aOR = 0.55, 95%CI: 0.34-0.87) and those with a family history of cancer (aOR = 0.66, 95%CI: 0.50-0.87) were less likely to accept stopping CRC screening at the age of 80 years. In contrast, people who resided in a metropolitan region (aOR = 1.86, 95%CI: 1.29-2.68) and exercised regularly (aOR = 1.42, 95%CI: 1.07-1.89) were more likely to accept the upper age limit.

Subgroup by CRC screening history

Table 3 shows the results of multivariate regression analysis with stratification according to CRC screening experience. Among never-screened individuals, women were less likely to agree with 80 years as a good age at which to stop CRC screening (aOR = 0.25, 95%CI: 0.08-0.82). However, participants living with their spouse (aOR = 3.71, 95%CI: 1.10-12.48) or who had smoked more than five packages in their lifetime (aOR = 7.1, 95%CI: 1.2-40) were more likely to accept the upper age limit. Among everscreened people, metropolitan residents (aOR = 1.80, 95%CI: 1.23-2.65) and individuals who exercised at least one time per week (one to two days per week aOR = 1.50, 95%CI: 1.02-2.20; more than three days per week (aOR = 1.49, 95%CI: 1.10-2.02) were more likely to accept the upper age limit for CRC screening. Respondents who had a family history of cancer were less likely to accept the CRC screening threshold (aOR = 0.61, 95%CI: 0.46-0.82).

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of the study participants

CRC: Colorectal cancer; FOBT: Fecal occult blood test; NCSP: National Cancer Screening Program.

DISCUSSION

In this study, about 80% (1554/1922) of the participants agreed with ceasing CRC at an age of 80 years. This rate is much higher than rates reported in previous studies[16-18]. Pilot results from Lewiset al[17]indicated that 76% of respondents planned to undergo screening for colon cancer as long as they lived and that 64% thought that everyone should get CRC screening as long as they live, although the study was primarily focused on life expectancy and included a small sample size. One study of older adults in England noted that most of the participants disagreed with an age-based stoppage policy, and people wanted to continue to be invited for cancer screening rather than comply with the current stoppage age[18]. Another study of patients’ attitudes toward individualized recommendations to stop CRC screening reported that 64% of respondents found encouraging the use of age to decide when to stop screening as moderately to strongly reasonable[16]. The high rate of acceptance in the current study of setting an upper age limit at 80 years could be considered reasonable and in keeping with these studies, as the life expectancy at birth of the Korean population is very close to 80 years (82.7 years, 2017)[22], which would indicate that the participants want to undergo CRC screening until the end of their life.

Our study highlighted a negative association between CRC screening history and the acceptance of CRC screening stoppage. People who had been examined for CRC screening less favored setting an age limit for CRC screening. This finding is consistent with a study in England in which participants who had undergone CRC screening expressed stronger intentions to seek screening after the proposed upper threshold age than participants who had never undergone CRC screening[18]. One of the possible explanations for this result may be related to the belief that screening will absolutely benefit one’s health. In general, those who have been screened tend to overestimate the benefits of screening and to underestimate the harms caused by screening. Accordingly, they may misunderstand stopping cancer screening as depriving them of its benefits. Also, people who are more health-conscious are more likely to undergo screening and to want to receive screening more frequently[23,24]. Interestingly, in the current study, people with a family history of cancer and those who had ever been screened for other types of cancer were less in favor of setting an upper age limit for CRC screening.

As a golden standard in colorectal screening, colonoscopy is being increasingly used worldwide. Along with that trend, complications associated with colonoscopy are garnering increasing interest among health experts. Complications with colonoscopy can occur both during the procedure, during bowel preparation (e.g., electrolyte imbalance and dehydration), and after the colonoscopy (e.g., infection)[25]. The continuous use of colonoscopy may also pose a greater risk of serious bleeding, perforation, and cardiovascular/pulmonary-related events in older (> 65 years) and much older (> 80 years) adults, especially those who with underlying diseases[26]. Moreover, in previous studies[27,28], a higher colonic polyp prevalence was noted in older patients, for which polypectomy procedures are usually indicated, posing an additional cause of bleeding, pain, and perforation. Indeed, a systematic review and meta-analysis by Dayet al[29]demonstrated that much older adults face a 70% higher risk of experiencing a colonoscopy complication overall and a 60% higher risk of perforation in comparison with younger patients. However, with careful assessment of a patient’s overall health condition and age, the risk of colonoscopy-related adverse events is relatively low for almost all age groups[26]. Thus, CRC screening at an older age should be carefully implemented such that its benefits overweighs its harms.

There are several limitations that may affect the interpretation of our results. First,the cross-sectional study design limits the ability to infer causal relationships for the noted associations. Second, information bias could have occurred due to the selfreports of history of lifetime smoking, drinking, and physical activity and the intensity thereof. Finally, we could not document awareness of the benefits and harms of screening, which can be predictors of a person’s attitudes toward screening. Future studies that account for this information in the study design and analyses could be beneficial. Despite all of the above limitations, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to address views on the upper threshold of age for CRC screening and associated factors in South Korea. Our study results provide perspectives that should be considered, in addition to scientific evidence, when developing population-based cancer screening policies and programs. It will facilitate the implementation of scientific evidence-based screening programs.

Table 2 Logistic regression for factors associated with acceptance of an upper age limit for colorectal cancer screening at 80 years (n = 1992)

cOR: Crude odds ratio; aOR: Adjusted odds ratio; CRC: Colorectal cancer; FOBT: Fecal occult blood test; NCSP: National Cancer Screening Program.

In conclusion, the majority of the participants in this study agreed with the recommendation of the National Cancer Center of Korea to stop CRC screening at the age of 80 years. Nevertheless, CRC screening history was found to be negatively associated with the participants’ acceptance to stop CRC screening at 80 years. In order to reduce unnecessary burden that may arise from cancer screening, it is imperative to explore ways to provide balanced information on the benefits and risks of screening, including setting an upper age limit.

Table 3 Logistic regression for acceptance of an upper age limit for colorectal cancer screening at 80 years according to colorectal cancer screening history (n = 1992)

aOR: Adjusted odds ratio; CRC: Colorectal cancer; NCSP: National Cancer Screening Program.

Figure 1 Rates of acceptance of an upper age limit for colorectal cancer screening at 80 years according to colorectal cancer screening history. CRC: Colorectal cancer; FOBT: Fecal occult blood test.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common types of cancer worldwide. Screening for CRC is recognized as an effective intervention through which to reduce the numbers of new cancer cases and cancer deaths. In South Korea, although the Korea National Cancer Center recommends CRC screening for adults aged 45 to 80 years, the Korea National Cancer Screening Program currently provides CRC screening for individuals aged 50 years and older with no upper age limit.

Research motivation

In general, people are likely to only pay attention to the benefits of cancer screening and to neglect its risks. Most consider the benefits of cancer screening as being far greater than the risks and are unaware that any potential benefits and harms can vary with age. Although several CRC screening guidelines recommend setting an upper age, there is a lack of information on perceptions and acceptance of an upper age limit for CRC screening.

Research objectives

In this study, we aimed to investigate acceptance of an upper age limit for CRC screening and factors associated therewith among cancer-free individuals targeted for screening in South Korea.

Research methods

The present study analyzed data from the Korea National Cancer Screening Survey 2017, a nationally representative survey targeted for cancer screening. A total of 1922 participants were included in the final analysis. The baseline characteristics of the study population are presented as unweighted numbers and weighted proportions. Both univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were developed to examine factors related with acceptance of an upper age limit for CRC screening. Subgroup analysis was also applied.

Research results

About 80% of the respondents agreed that CRC screening should not be offered for individuals aged older than 80 years, especially respondents who had never been screened for CRC (91%). Overall, the factors significantly associated with acceptance of an upper limit age among the respondents were residential region, cancer screening history, family history of cancer, and physical activity. By subgroup analysis, we found gender, marital status, and lifetime smoking history among never-screened individuals and residential region, family history of cancer, and physical activity among never-screened individuals to be associated with acceptance of an upper age limit.

Research conclusions

The majority of the participants in this study agreed with the recommendation of the National Cancer Center of Korea to stop CRC screening at the age of 80 years. CRC screening history was a strong factor associated with acceptance. In order to reduce unnecessary burden of cancer screening programs, it is recommended to provide balanced information on the benefits and risks of screening.

Research perspectives

Our study results provide perspectives that should be considered, in addition to scientific evidence, when developing population-based cancer screening policies and programs. In the future, further research on attitudes and preferences toward cancer screening policies in the general population are required.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the International Cooperation & Education Program (NCCRI·NCCI 52210-52211, 2020) of National Cancer Center, South Korea for supporting the education and training of Xuan Quy Luu.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Histopathological landscape of rare oesophageal neoplasms

- Details determining the success in establishing a mouse orthotopic liver transplantation model

- Modified percutaneous transhepatic papillary balloon dilation for patients with refractory hepatolithiasis

- Serum ceruloplasmin can predict liver fibrosis in hepatitis B virusinfected patients

- Transarterial chemoembolization with hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy plus S-1 for hepatocellular carcinoma

- Intestinal NK/T cell lymphoma: A case report