Deducing the Intonation of Chinese Characters in Suzhou-Zhongzhou Dialect by Its Singing Technique in Kunqu: A New Probe into Ancient Chinese Phonology

2020-08-10LingZhu

Ling Zhu

Soochow University, China

Abstract Kunqu is a comprehensive art which is considered to be an epitome of the achievements of Chinese Xiqu. It was unanimously selected by UNESCO from the first round of entrants for the category of “Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity”, with emphasis on its heritage value as embodied in language, literature, music, singing technique, dance, performance, set design, makeup, and more, and has been given the status of living fossil by artists both in China and abroad. Based on the relationship between the intonation of Chinese characters and singing techniques, especially the criterion in Kunqu that the “singing technique follows the intonation of a Chinese character”, we attempt to deduce the intonation of Chinese characters in the Suzhou-Zhongzhou dialect based on its singing technique. Specifically, we deduce the archaic intonations of Chinese characters by the exclusive singing techniques in Kunqu for the purpose of exploring a new approach to Chinese phonology of the Ming and Qing dynasties from an interdisciplinary perspective of artistic criterion and linguistics.

Keywords: Kunqu, singing technique, Chinese phonology, heritage value, interdisciplinary research

1. Introduction

In ancient Chinese phonology, researchers, by and large, turn to rhyming dictionaries and dialects to trace back the pronunciation and intonation of a character. However, besides rhyming dictionaries and dialects, is there any other resource that can help with the study? An interdisciplinary approach may help us break through the cognitive barriers and get unexpected discoveries, and the exploration of archaic Chinese phonology from the perspective of the art of Chinese Xiqu1is a case in point. Compared with the other two ancient theatrical forms in the world, the tragedy of ancient Greece and Kutiyattam of ancient India, Chinese Xiqu exceeds in variety. According to the latest statistics from the National Xiqu Genre Survey by the central government of China, up to August 31st, 2015, there were 348 Xiqu genres in China.2Despite this big amount, only a few of them, such as Yiyangqiang3, Kunqu, Qinqiang4, Pihuangqiang5, etc., are considered as “initial species” in the extant genres of Xiqu (Zhu, 2018, p. 10).

On May 18th, 2001, UNESCO announced the first batch of the representative list of the “Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity”. Of the 19 items selected worldwide, four were unanimously approved, including China’s Kunqu (Zhu, 2019, pp. 3-16). Kunqu, originated from Suzhou in the late Yuan Dynasty and the early Ming Dynasty, is a concentrated embodiment of the artistic achievements of Chinese Xiqu. “It provides sufficient nourishment for the development of later local Xiqu with delicate and graceful tunes, impressive and sparkling words, and a singing and dancing performance style” (Zhu, 2013, p. 71). The beginning of the 21st century witnessed a resurrection of Kunqu that has gradually become a way of “seeking a distinctive elite identity” (Ma, 2019, p. 2) by the youngsters and the new middle class in China. As a comprehensive art that has been mature for hundreds of years, the heritage value of Kunqu is reflected in many fields, such as language, literature, music, singing technique, dance, performance, acrobatics, props, makeup and so on. At the same time, Kunqu has much to offer in the form of auxiliary value in the research of these fields.

2. Suzhou-Zhongzhou Dialect: The Phonetic Basis of Kunqu

Each genre of Chinese Xiqu has its specific way of articulation which is, more often than not, influenced by the dialect where it was born in order for it to be more easily understood by local audiences. However, Kunqu, though born in the southern city of Suzhou in Jiangsu Province, where Wu is the dialect, turned out to be a popular Xiqu all over China during the Ming and Qing dynasties. There is no denying that Kunqu owes a lot to its articulation. As a matter of fact, the Kunshan Tune6, created by musicians represented by Gu Jian at the turn of Yuan and Ming dynasties, was only one of the four outstanding tunes in Southern China at that time. It was only after Master Wei Liangfu’s musical reform in articulation, singing techniques, and musical accompaniment that Kunqu was crowned by musicians as well as audience the “King of Chinese Xiqu”. One of the most important reasons for this is that the phonetic basis of Kunqu is not the dialect of its birthplace, but rather the Suzhou-Zhongzhou dialect, which is understood by people both in the north and the south of China.

The Zhongzhou dialect is a dialect employed in the Central city of Kaifeng of Henan Province (the then Zhongzhou area), capital of Northern Song Dynasty, and it was the Mandarin popular in China in the Ming Dynasty. Historians’ opinions used to vary when it came to whether there had been a Mandarin Chinese in the Ming Dynasty. Lu Guoyao points out in his essay “The problem of Mandarin and its basic dialect in the Ming Dynasty: on Matteo Ricci's Reading Notes about China” that the book mentioned in the title

…clearly describes the existence of Mandarin in the Ming Dynasty, which was a common language of the whole country, superior to other dialects. It was widely used, especially among officials and intellectuals. Even illiterate women and children could understand it well and it was the Mandarin Chinese that foreigners learnt at that time. (Lu, 1985, p. 85)

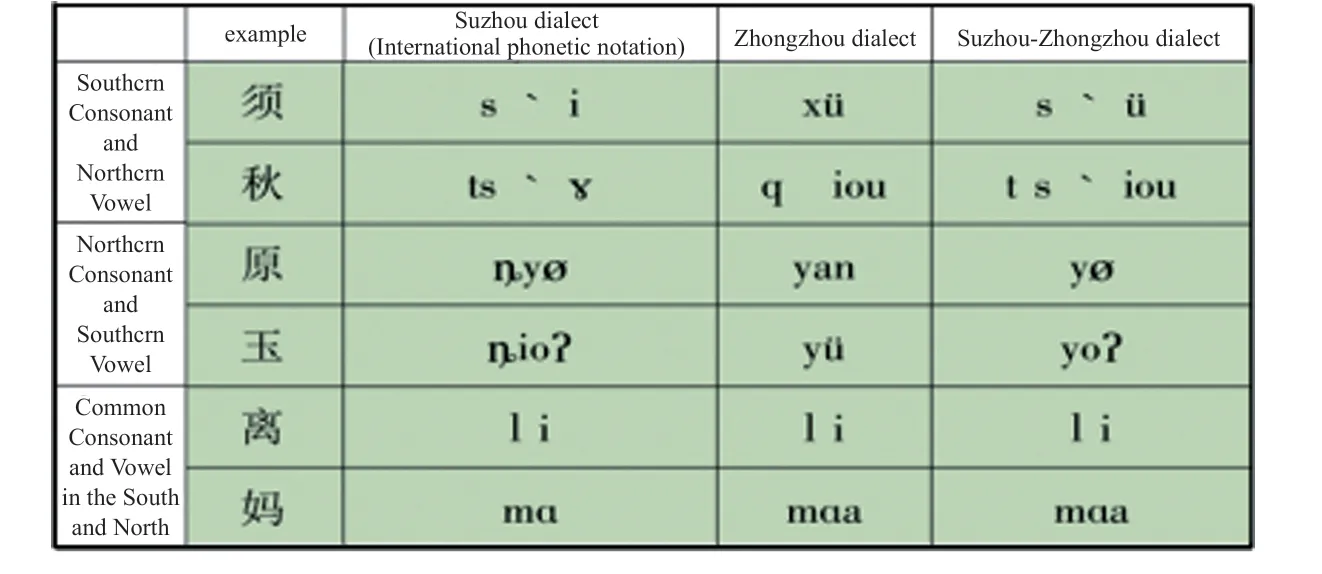

Here, the term Mandarin Chinese refers to Zhongzhou dialect. Later, the Southern Song Dynasty relocated the capital from Kaifeng to Hangzhou (called Lin’an then) of Zhejiang Province, a southern city. The dialect of Zhongzhou, originally used as the common official language, was gradually combined with the dialects of some southern regions to brew different southern official dialects, which were collectively referred to as the Southern Zhongzhou dialects, among which was included the Suzhou-Zhongzhou dialect. Suzhou-Zhongzhou is an ingenious combination of the consonants and vowels of the dialects from Suzhou and Zhongzhou, and is closely related to these dialects in terms of tone pitch, special articulation of fixed consonants, articulation of vowels, and so on (Gu, 1987, p. 72). Gu Lingsen categorizes such a combination mode into three main types, that is, Southern Consonant and Northern Vowel, Northern Consonant and Southern Vowel, and Common Consonant and Vowel in the South and North, with the following examples (Gu, 2008, p. 161):

Table 1. Examples of combination mode of Suzhou-Zhongzhou dialect

As for the pronunciations of Chinese characters such as 须 (pronounced as xu in Chinese pinyin) and 秋 (pronounced as qiu in Chinese pinyin) in the first type, whose consonants derive from the Suzhou dialect and vowels derive from the Zhongzhou dialect, we categorize them into Southern Consonant and Northern Vowel for their ways of combining the consonants and vowels. Chinese characters such as 原 (pronounced as yuan in Chinese pinyin) and 玉 (pronounced as yu in Chinese pinyin), whose pronunciations are combinations of Zhongzhou consonants and Suzhou vowels, fall into the second type that is called Northern Consonant and Southern Vowel. There are some characters, such as 离 (pronounced as li in Chinese pinyin) and 妈 (pronounced as ma in Chinese pinyin), whose pronunciations are the same in both Suzhou and Zhongzhou dialects, so we put them in the category of Common Consonant and Vowel in the South and North. From the three types of combination above we can learn that the Suzhou-Zhongzhou dialect has a wide and familiar phonetic basis for both southerners and northerners, and as such it is not difficult to understand for both of them. In addition, it bears the characteristics of both the strong Northern dialect and the soft, graceful Suzhou dialect with distinctions in cadence and intonation, all of which help to highlight the musicality of the Chinese language; thus, it is suitable to be incarnated and conveyed through Chinese Xiqu. Because of this, the Suzhou-Zhongzhou dialect was adopted by Wei Liangfu, ameliorated several times from the early Ming Dynasty to the middle of the Qing Dynasty, and finally became the phonetic basis of Kunqu, a language of hardness and softness.

3. The Correspondence between Kunqu and Chinese Phonology

There is a strict singing criterion in Kunqu that requires an awfully high conformance between the singing technique and the articulation of its lyrics, which is commonly known as the “singing technique follows the intonation of a Chinese character”. In other words, the selection of a singing technique is subject to the intonation of a Chinese character. Here the singing technique refers to a distinctive way of articulating a Chinese character and manipulating its intonation with a Kunqu musical accompaniment, which depends on the consonant, vowel, intonation of the character, and the emotions it carries (Zhu, 2019, p. 314). As we have discussed above that the Suzhou-Zhongzhou dialect was adopted to be the phonetic basis of Kunqu, the aesthetic for Kunqu articulation in song is based on the articulation criteria for Suzhou-Zhongzhou in speech. As a matter of fact and as is known to all Kunqu musicians and amateurs, all of those identifying singing techniques of Kunqu reflect the articulation characteristics of the Suzhou-Zhongzhou dialect as well.

A prerequisite of singing correctly in Kunqu is to make clear the pronunciations and intonations of Chinese characters. In the composition of lyrics and music as well as in singing, senior musicians of previous dynasties never failed to set articulation correction as a starting point for training, because it is impossible for a singer to sing correctly if he or she articulates wrong. Therefore, in Kunqu there is another vivid way of expressing the notion of “singing a song”, that is “measuring a song”. “Measuring” in this context takes its original meaning of calculating the length of something with a tool like a ruler. That is, to be strict with singing in accordance with its requirements, the purpose of which is to take the articulation of characters and singing techniques into the criterion of singing performance. Kunqu’s singing techniques follow and serve the articulations of Chinese characters; at the same time, articulations of Chinese characters are highlighted by Kunqu singing techniques.

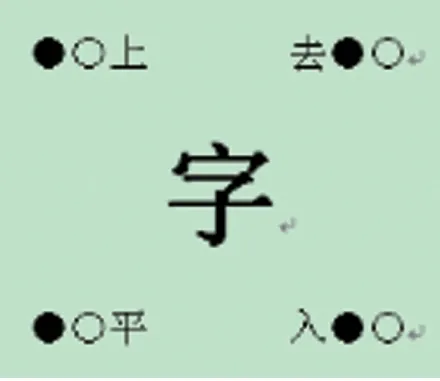

Figure 1. An annotation of intonations in Kunqu Gongchepu

Gongchepu (工尺谱) or the Gongche Score is a traditional Chinese musical notation that takes some Chinese characters such as 上 (pronounced as shang in Chinese pinyin), 尺 (pronounced as che in Chinese pinyin), 工 (pronounced as gong in Chinese pinyin), 凡 (pronounced as fan in Chinese pinyin), 六 (pronounced as liu in Chinese pinyin), 五 (pronounced as wu in Chinese pinyin), 乙 (pronounced as yi in Chinese pinyin) as scores instead of do, ri, me, fa, so, la, ti in the stave. Gong (工) and Che (尺), two of the characters used, were taken to form the name of this musical notation, and Gongchepu is a must in Kunqu learning. In a Gongchepu of Kunqu, the intonation of a Chinese character from the lyrics is annotated to one of the four corners of this character (See Figure 1). A level or rising tone is annotated to the left bottom of the character, a falling-rising tone the left top, a falling tone the right top,

and an abrupt and click entering tone the right bottom. “○” is a mark of Yin, indicating the pronunciation of this character should be light and voiceless, while “●” is a mark

of Yang, indicating a heavy and voiced pronunciation of the character. It is based on such an annotation of the intonation of a character that musicians choose different scores to compose Kunqu music. To be specific of choosing the score, to set the pitch of a level tone first, to reflect the pitch of the intonation of a given character by the fluctuations, say, rising or falling, of the melody, and then to choose a correspondent singing technique in Kunqu to convey such fluctuations. See Table 2 (Wu, 1993, p. 102):

Table 2. A schedule of proportions of Kunqu singing technique and the rise and fall in pitch

The singing technique of Kunqu has two functions. One is to reflect the intonation of a given Chinese character, which is taken as a basis in composing a notation. For instance, a character with a level tone is sung in only one note to reflect its characteristics of flat and straight without twists and turns, while a rising tone is sung in two notes with the first low and the second higher than the first one; that is an ascending pitch, which is consistent with the pitch contour of the intonation of the character. The other function is to standardize the singing techniques. For example, a character with a Yin falling-rising tone is applicable to Huoqiang7(嚯腔) and Hanqiang ( 腔), and Yang and Yin falling tones are applicable to Huoqiang (豁腔) for the purpose of being pleasant to the ear as well as reflecting the relationship between the intonation of the character and its notes. This is a distinctive feature of Kunqu that differs from other genres of Xiqu in singing. It is obvious that “singing technique follows the intonation of a Chinese character” is a musicalization of the articulation of Chinese characters. Specifically, it is a process of presenting the Suzhou-Zhongzhou dialect with Kunqu music and singing techniques.

For most non-native speakers learning the modern Chinese language today, the distinction between the tones of Chinese characters is often a challenge and a big headache. In fact, the situation in Kunqu singing is even more complex: level and rising tone (平), falling-rising tone (上), falling tone (去), and entering tone (入) each consist of Yin (light and voiceless tone) and Yang (heavy and voiced tone). There is no entering tone in modern Chinese, as in the Phonology of Central China of the Yuan Dynasty, the entering tone was modified to the former three ones. This modification is based on the state of northern pronunciations; however, in southern singing techniques the entering tones of Chinese characters still persevere today. The singing techniques of Kunqu have to be diversified, for they are required to reflect the characteristics of such rich intonations of Chinese characters. According to incomplete statistics, there are more than 30 Kunqu singing techniques, and each of them has its applicable intonation or intonations (Zhu, 2019, p. 314).

4. To Deduce the Intonation of Chinese Characters by Kunqu

According to the criterion of “singing technique follows the intonation of a Chinese character”, there is a certain correspondence between the intonation of a Chinese character and its singing technique in Kunqu. On the one hand, an intonation may adopt one or several singing techniques; meanwhile, a singing technique is applicable to one or several intonations. We interpret this as a one-to-many relationship. On the other hand, some singing techniques are applicable to only one intonation, which is a one-to-one relationship. The latter is what we are focusing on. Through research, we find that some singing techniques are exclusively applicable to a certain intonation, for example, Hanqiang ( 腔) is exclusively applicable to a falling-rising tone, Huoqiang (嚯腔) to a Yang falling-rising tone, Huoqiang (豁腔) to a falling tone, Huayueqiang (滑跃腔) to a Yang falling tone, etc. (Wu, 2002, pp. 557-562). From this discovery, we can infer that although a certain intonation of the character does not necessarily adopt the same singing technique in Kunqu, the adoption of an exclusive singing technique can be recognized as an identifying feature of a certain intonation. For instance, a Chinese character with a falling-rising tone can be sung in techniques such as Hanqiang ( 腔), Huoqiang (嚯腔), and so on. But because Hanqiang (腔) is an exclusive singing technique for a falling-rising tone in Kunqu, the intonation of the character sung in it must be a falling-rising tone rather than any other tones. In view of this, if we can judge and make sure which exclusive singing technique is adopted by a Chinese character, then we can infer its intonation in the Suzhou-Zhongzhou dialect of Ming and Qing dynasties, which is Kunqu’s phonetic basis. We define this process as “to deduce the intonation of a Chinese character in the Suzhou-Zhongzhou dialect by its singing technique in Kunqu”. Figure 2 shows the relationship between the intonation of Chinese characters and the singing techniques of Kunqu. To be specific, the intonation of a Chinese character decides the adoption of its singing technique in Kunqu; meanwhile, we can reverse this process to deduce the intonation of a Chinese character by a certain singing technique it adopts.

Figure 2. The relationship between the intonations of Chinese characters and the singing techniques of Kunqu

This deduction is probably confronted with a suspicion; that is, how can we ensure that every Kunqu singer practices an exclusive singing technique identically in reality instead of misleading us by his or her arbitrary use of another singing technique such that we deduce an incorrect intonation of a Chinese character? According to the author’s personal experience of Kunqu learning of 15 years as well as a broad consensus among Kunqu musicians, as a mature art that has been polished for more than six hundred years, there is a considerably strict criterion for the practice of singing techniques for the lyrics in Kunqu. Some of the singing techniques are marked with symbols in Gongchepu, for example, a Dieqiang (叠腔) is marked with a symbol of “·” and a Huoqiang (豁腔) is marked with a symbol of “ᴗ”. In view of the particularity of the oral and intangible heritage of Kunqu, it is difficult for all singing techniques to be recorded and expressed clearly in words or symbols. In practice, the inheritance of Kunqu mainly relies on the oral imparting and physical instruction of teachers, and the acquisition and exercise of learners. It is impossible for one to acquire the singing techniques of Kunqu by just reading books without a teacher’s face-to-face instruction. According to statistics, there are a total of 411 Kunqu selected scenes handed down (with performance or teaching records in the past 60 years) (Zhou, 2011, table of contents), all of which are passed down this way in the sense of an inherited pedigree. The adoption and practice of a singing technique have become a common understanding and conventional rules among the musicians and the singers of Kunqu, and have even been used as criteria to judge whether one’s singing is standard. There has been no significant variation in sung tones since the creation of the plays, therefore it is reasonable in theory and feasible in operation to deduce the intonation of a Chinese character in the Suzhou-Zhongzhou dialect by its singing technique.

Let’s try deducing, according to Kunqu’s Gongchepu, the phonology of Chinese characters by some singing techniques mentioned above.

4.1 Level, rising, falling-rising and falling tones

The Peony Pavilion is an acknowledged masterpiece in Kunqu. In the famous scene of “Visiting the Garden”, there is a lyric composed in the Qupai8of Zuifugui9that reads “艳晶晶花簪八宝填”. In the singing of the Chinese character 宝 (pronounced as bao) in this lyric, the singer rises in tune, makes a big dive by an ascending appoggiatura, and then enters the original note in a very short time. Based on the professional knowledge of Kunqu, this is a unique way of practicing Hanqiang ( 腔). According to the singing criterion, Hanqiang ( 腔) is an exclusive singing technique for Chinese characters of falling-rising tones. From this we can deduce that 宝was a character of falling-rising tone in Suzhou-Zhongzhou dialect during the Ming and Qing dynasties. Figure 3 is a partial content of Gongchepu for this lyric.

Figure 3. The Gongchepu of 宝10

In the scene “Sweeping the Flowers” of The Handan Dream, there is a lyric of “东老贫穷” under the Qupai of Shanghuashi. At the lower second note in the singing of 老 (pronounced as lao), the larynx of a singer temporarily stops the airflow, creating a feeling of regurgitation, which is an identifying feature of the practice of Huoqiang (嚯腔). As is known to all Kunqu practitioners, Huoqiang (嚯腔) is an exclusive singing technique for a character of a Yang falling-rising tone, so we are certain that 老 was a character of a Yang falling-rising tone in the Suzhou-Zhongzhou dialect. See Figure 4.

Figure 4. The Gongchepu of 老

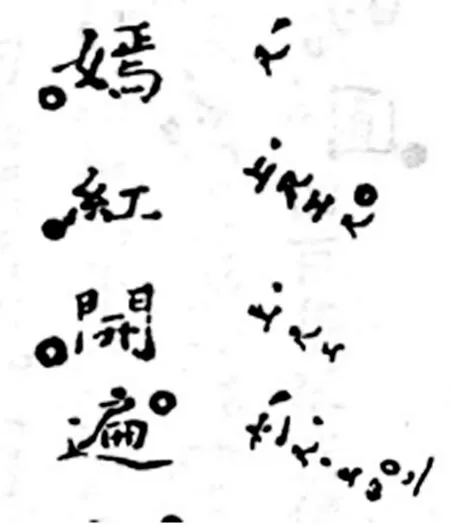

Again in the scene of “Visiting the Garden” of The Peony Pavilion, there are lyrics of “梦回莺转” and “姹紫嫣红” under the Qupai of Raochiyou and Zaoluopao respectively. The first note is followed by a degree and two degrees of ascending appoggiatura in the singing of both 梦 (pronounced as meng) and 遍 (pronounced as bian), which is a typical performance of Huoqiang (豁腔). There is a popular saying in Kunqu circles that whenever one sings a character with a falling tone, one is supposed to adopt the singing technique of Huoqiang (豁腔). Based on this rule, and practice in reality, we learn that 梦 and 遍 in the original lyrics were characters of falling tones in the Suzhou-Zhongzhou dialect. See Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure 5. The Gongchepu of 梦

Figure 6. The Gongchepu of 遍

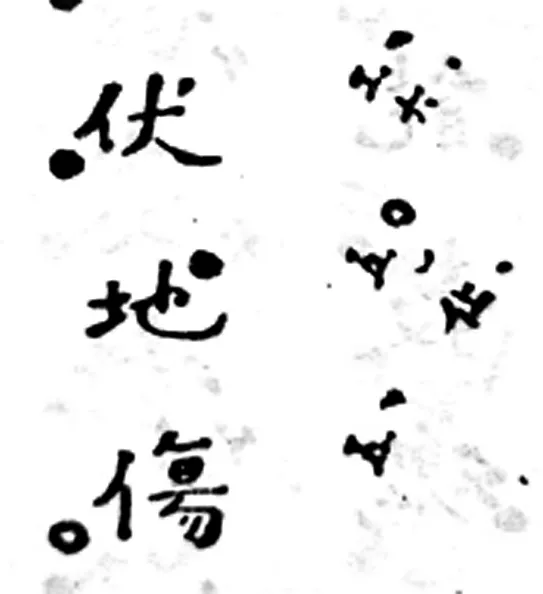

In the scene “Startled by the Rebellions” of The Palace of Eternal Youth, there is a character 淡 (pronounced as dan) in the lyrics of “天淡云闲” under the Qupai of Fendieer, and in the scene “Tears to the Statue” of the same play, there is a character 地 (pronounced as di) in the lyric of “旧宫娥伏地伤” under the Qupai of Ersha. Both the singing of 淡 and 地 is composed of three notes, where the first two slide and ascend high and the third one falls and is sung as usual. This style of singing sounds smooth but with ups and downs and full of charm, is obviously a distinctive feature of Huayueqiang (滑跃腔). According the criterion of Kunqu, Huayueqiang (滑跃腔) is an exclusive singing technique for a character of a Yang falling tone, so that we discover both 淡 and 地 were characters of falling tones in the Suzhou-Zhongzhou dialect. See Figure 7 and Figure 8.

Figure 7. The Gongchepu of 淡

Figure 8. The Gongchepu of 地

4.2 Entering tones

There used to be no agreement among academics on whether there were Chinese characters pronounced with entering tones in the common language of the Ming and Qing dynasties (Lu, 1985, p. 49). In fact, convincing evidence of and answer to this problem in Chinese phonology reveals itself in Kunqu through the deduction we propose in this article. Qupai of Kunqu include the North Qupai and the South Qupai, which are different in musical structure and phonological characteristics. The differences in musical structure are mainly manifested in three aspects. First, there are different scales in the north and south Qupai. A pentatonic scale is used in the South Qupai, while a heptachord is used in the North Qupai. Second, the number of boardstrikings and inserted characters is different. There are boardstrikings of comparatively fixed number and less inserted characters in the South Qupai, while in the North Qupai the number of boardstrikings and inserted characters is much more flexible. Third, the musical styles are quite different with the south, where they are gentle and lingering, and the north, where they are strong and energetic. The difference in the phonological characteristics is mainly reflected in the existence of characters of entering tones, for there are no entering tones in the North Qupai.

It is not easy for modern Chinese speakers, especially for those from the north, to pick out characters of entering tones in archaic Chinese language because there are such characters neither in the modern Chinese language nor in the archaic northern phonetics represented by the Zhongzhou dialect. Even some lyricists and librettists in the Ming and Qing dynasties did not make an intentional distinction between the entering tones from others in composing lyrics. In order to help Kunqu break through the regional restrictions and spread throughout the country, the lyricists and librettists at that time employed the Zhongzhou vowels with the nature of common language when composing the lyrics. That is, according to Zhou Deqing’s Phonology of Central China, the entering tones were transformed to other tones. Nevertheless, the situation is different in Kunqu. In singing a South Qupai, singers still follow the norms of the Hongwu Phonology, which was compiled by Yue Shaofeng and Song Lian. With the purpose of reflecting the differences between sentimental colorings of the South and North Qupai, especially highlighting the lingering melodies and the ups and downs of the South Qupai, the entering tones that had been transformed to other tones were restored to their original tones in the singing of Kunqu (Yu, 2009, p. 64). This is what Shen Chongsui said in his Handbook for Singing a Song: “Though the lyrics are composed to the norm of Zhou Deqing’s Phonology of Central China where one cannot find an entering tone, in the singing of a South Qupai of Kunqu, the intonations of characters should follow The Hongwu Phonology where entering tones are restored and preserved” (Shen, 1959, p. 235).

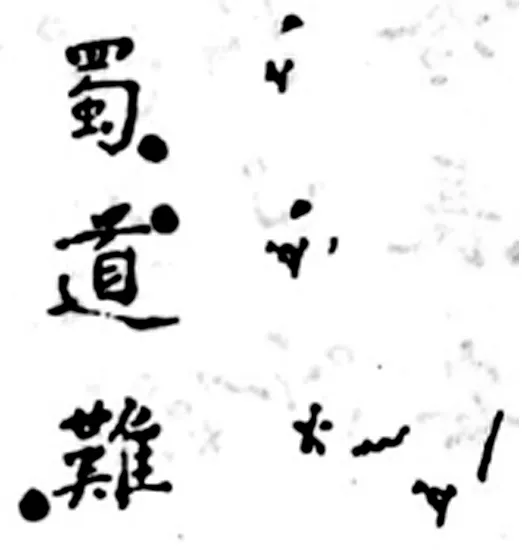

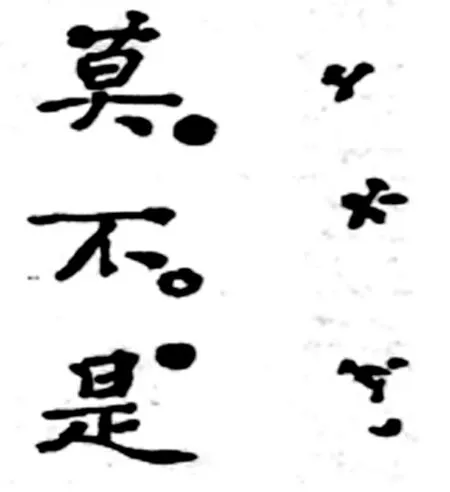

The sound of an entering tone is quite brief in that as long as it is voiced, it comes to an abrupt end. In accordance with the Kunqu criterion of having the “singing technique follows the intonation of a Chinese character”, an entering tone adopts a Duanqiang (断腔) in South Qupai, just as the popular saying goes that whenever one sings a character with an entering tone, one is supposed to adopt the singing technique of Duanqiang (断腔). Based on this, a Duanqiang (断腔) is often recognized as an identifying symbol of an entering tone. In The Girl Washing Silk, which “is celebrated as the play that established Kunqu as the dominant dramatic style, the elite, elegant style which endured for three centuries and is still favored today among the most dedicated aficionados of the classical theater” (Birch, 1995, p. 63), there is a 拾 (pronounced as shi) in the lyric of “拾翠寻芳” under the Qupai of Putianle. There is also a 蜀 (pronounced as shu) from the lyric of “怎样支吾蜀道难” under the Qupai of Nanweisheng in The Palace of Eternal Youth and a 莫 (pronounced as mo) from the lyric of “莫不是步摇得宝髻玲珑” under the Qupai of Yudenger in The Romance of the Western Chamber11. In the singing of these three characters in Kunqu, 拾, 蜀, and 莫, the articulation is so short that it comes to an abrupt halt, but the halt is different from a general rest in music for it is soft and does not impair the beauty of the sound, which indicates an obvious adoption of Duanqiang (断腔). Though the intonation of 拾 is a Yang rising tone, 蜀 is a falling-rising tone, and 莫 is a falling tone in the modern Chinese language, all three are sung with the typical singing technique of Duanqiang (断腔) in the South Qupai of Kunqu. Therefore, we can deduce that these three characters are articulated with entering tones in the Suzhou-Zhongzhou dialect of the Ming and Qing dynasties. By analogy, characters of level, rising, falling-rising, and falling tones in the modern Chinese language that adopt a Duanqiang (断腔) in the singing of a South Qupai of Kunqu were probably characters of entering tones in the Suzhou-Zhongzhou dialect in the Ming and Qing periods. See Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11.

Figure 9. The Gongchepu of 拾

Figure 10. The Gongchepu of 蜀

Figure 11. The Gongchepu of 莫

5. Conclusion

From the examples discussed above, we have demonstrated the process of deducing some intonations of Chinese characters in the Suzhou-Zhongzhou dialect by the singing techniques in Kunqu, including deducing a certain intonation from an exclusive singing technique, such as a falling-rising tone from a Hanqiang (腔), a Yang falling-rising tone from a Huoqiang (嚯腔), a falling tone from a Huoqiang (豁腔), and a Yang falling tone from a Huayueqiang (滑跃腔), besides those characters sung with Duanqiang (断腔) in South Qupai of Kunqu, which were probably ones of entering tones. Based on the Kunqu criterion of a “singing technique follows the intonation of a Chinese character”, the deduction is a process of exploring a linguistic phenomenon through a mature artistic criterion of Kunqu, which may be a new probe into the studies of ancient Chinese phonology of the Ming and Qing dynasties. This approach requires not only the keen insight of linguists, but also the skillful singing techniques of Kunqu musicians and singers, which is an interdisciplinary entry point. Meanwhile, it dawns on us that in the long period of Chinese phonological changes, some of the ancient memories that disappeared in the long river of history or in our unawareness are found preserved in the living fossil of Kunqu in their unique form and have been passed down to the present day, inspiring us to further explore the treasure of the art of Kunqu and find more heritage value.

Notes

1 Xiqu is a stylized classic performing art of China that embraces singing, speech, music, dancing, acrobatics, etc.

2 Data from: The Press Conference on the Results of National Xiqu Genre Survey. Website: http://www.scio.gov.cn/xwfbh/gbwxwfbh/xwfbh/whb/Document/1614324/1614324.htm

3 Yiyangqiang is a Chinese Xiqu originating from Jiangxi Province.

4 Qinqiang is a Chinese Xiqu originating from Shaanxi Province.

5 Pihuangqiang is a cluster of Chinese Xiqu that takes Xipi and Erhuang as its main tunes, including Huiju (Anhui Xiqu), Hanju (Wuhan Xiqu), Yueju (Guangdong Xiqu), Xiangju (Hunan Xiqu), Ganju (Jiangxi Xiqu), Guiju (Guangxi Xiqu), etc.

6 Kunshan Tune, born in Kunshan of Suzhou, is the music of Kunqu.

7 Huoqiang (嚯腔), Hanqiang ( 腔), Huoqiang (豁腔), Duanqiang (断腔), Huayueqiang (滑跃腔), and Dieqiang (叠腔) mentioned in this article are of identifying singing techniques of Kunqu. As the names of Huoqiang (嚯腔) and Huoqiang (豁腔) have the same Chinese pinyin as huoqiang, all of the singing techniques are presented with both Chinese pinyin and the characters to make a distinction.

8 Qupai is the name of a tune to which the lyrics are composed.

9 Zuifugui is the name of Qupai. As all the names of Qupai have little relationship with the content of lyrics today; we can only interpret them as markers.

10 All the figures of Gongchepu in this article are from partial contents of Zhou Qin’s Musical Notations of Inch Heart Study, published by Soochow University Press in 1993.

11 There are two editions of The Romance of the Western Chamber, the Northern and the Southern Edition. In this article we refer to the Southern Edition.

Acknowledgements

This research was sponsored by the Major Project of the National Social Science Fund The History of Chinese Xiqu in the 70th Anniversary of the Founding of New China (Jiangsu Province Volume) (Grant Number: 19ZD05), the Social Science Youth Fund of Jiangsu Province Translation Studies of Kunqu under the Strategy of Chinese Culture Going Out (Grant Number: 16YSC004). Sincere gratitude is extended to the anonymous reviewers for the constructive and insightful comments and suggestions, to Professor Ding Zhimin of Shanghai University, Researcher Gu Lingsen of China Kunqu Museum, and Editor Du Kun of China Social Science Daily for their generous providing of research data and enlightenment.

猜你喜欢

杂志排行

Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- A Statistical Approach to Annotation in the English Translation of Chinese Classics: A Case Study of the Four English Versions of Fushengliuji1

- Teaching Indigenous Knowledge System to Revitalize and Maintain Vulnerable Aspects of Indigenous Nigerian Languages’ Vocabulary: The Igbo Language Example

- Aspects of Transitivity in Select Social Transformation Discourse in Nigeria

- Towards Semiotics of Art in Record of Music

- Umwelt-Semiosis: A Semiotic Perspective on the Dynamicity of Intercultural Communication Process

- L3 French Conceptual Transfer in the Acquisition of L2 English Motion Events among Native Chinese Speakers