Aspects of Transitivity in Select Social Transformation Discourse in Nigeria

2020-08-10MohammedAdemilokunAdesojiBabalola

Mohammed Ademilokun & Adesoji Babalola

Obafemi Awolowo University, Nigeria

Abstract This article examines transitivity in the mediatised discourse of social transformation in Nigeria. Data for the study comprises texts on aspects of social transformation campaigns in Nigeria in the context of democracy, anti-corruption crusades, insecurity, and domestic violence. The data was drawn from speeches, radio commentaries, jingles, printed texts, interviews, tweets, and online newspaper comments about government actors and nongovernment actors covering the period between March 2013 to March 2018. This fiveyear span was informed by a wide gamut of negative realities in the nation which led to increased mediatisation of social transformation messages. The analysis of data is hinged on the transitivity system espoused in Halliday’s systemic functional linguistics and critical discourse analysis by Fairclough (1989; revised 2015) and Machin and Mayr (2012). Data analysis revealed that the different participants in the discourse deployed material processes, relational processes, and mental processes to negotiate the social transformation challenge and agenda in Nigeria. The presentation of the agents in relation to the processes in the discourse reflected positive in-group representation and negative-other representation for legitimation and manipulation. The study concludes that transitivity is a veritable tool in the discourse that primarily serves in foregrounding social problems in Nigeria while also affording social participation.

Keywords: critical discourse analysis, Nigeria, social transformation discourse, systemic functional linguistics, transitivity

1. Introductionn

The role of language in shaping human affairs and conditions is indubitable. Fairclough (2001, p. 73) captures the centrality of language to the (re)engineering of society when he says “discourse contributes to the creation and recreation of the relations, subjects … and objects which populate the social world”. Since language is a purveyor of ideology, which is the collective system of beliefs and ideas shared by a group that underlies their actions and informs their dispositions to real issues in the real life (Simpson, 1993), it ultimately affects their attitudes and actions. This explains why Fairclough (2003) asserts that discourse is a vehicle for the construction of social reality by shaping points of view through dominant ideologies in society.

Major events in the world in the last two decades have shown that language is a catalyst for engendering social mobilisation to entrench good governance, better citizenship, and sustainable development in human societies. For example, through the use of language in physical and virtual spaces, people have mounted pressure on governments, among others, to ensure that certain conditions are created in their societies. The Arab uprising is a typical representation of the agency of language in virtual spaces, especially social media, to catalyse social reformation. Similarly, in Nigeria, language served as a tool for the conveyance of the resistance ideology of Nigerians against the 2012 hike of petroleum prices by their government, ultimately leading to the reversal of the government’s decision.

The subject of social transformation in Nigeria, in particular, has received attention in Nigeria for quite some time, as different governments and civilians have articulated the need for the nation to experience real transformation as a prelude to national development (Omilusi, 2017). One major reason is due to increasing negative uprisings such as the Boko haram insurgency, kidnapping, democratic improprieties, large-scale corruption, and many others. Another major reason for the growth in social transformation campaigns in Nigeria can be said to be the increasing understanding among the government and people of the nation that language serves as a tool for national and social reformation. However, most of the earlier efforts on social transformation in Nigeria have tended to fail due to lack of continuity in government policies, inadequate will of political leaders to enforce penalties against citizens who flout the policies, and wanton disorderliness among citizens (Omilusi, 2017). That notwithstanding, social transformation campaigns have continued to be reinforced in the country in the present times in view of the many social problems and the attitudinal deficit in many citizens of the country.

Therefore, given the reinvigoration of social transformation discourse in Nigeria, aided by the growing digital cultures in the nation (Ademilokun, in press), the discourse represents a veritable domain for investigating the agency of language for social emancipation in the Nigerian context. However, even though this discourse has witnessed increased popularity in Nigeria, there is a paucity of research on the subject, especially from the linguistic perspective. Apart from Ademilokun (in press), which explores the discursive resources of social transformation advocacy in Nigeria, few other studies on the subject have focused on the religious and literary dimensions of the discourse (Burgess, 2012; Raphael, 2014; Saale, 2014; Ajiwe, Okwuosa & Okoronkwo, 2015).

The present study therefore intends to deepen linguistic enquiry into social transformation discourse in Nigeria, especially through the lens of the system of transitivity. Transitivity as an aspect of Halliday’s Systemic Functional Linguistics indexes an important kind of meaning in human communication which Halliday tags ideational meaning. Such meaning, as widely acknowledged, is concerned with the way the content of a communication is framed at the clause level (see Halliday, 1985; Fowler, 1986), thus showing the realities that inform human expressions and the impacts of such expressions on realities. Fowler (1986, p. 136) asserts that transitivity patterns index the worldview framed by the authorial ideology in a text. Therefore, since the discourse of social transformation in Nigeria is grounded in certain group ideologies shared by Nigerians, and so inform their participation in the discourse, a linguistic examination of the transitivity system of that discourse would reveal the nature of meanings produced by it and the ideologies underlying such meanings. Such a study, we believe, will also elucidate the social problems in the nation and the solutions to such problems as a guide for policymakers.

After this introductory background, we present a brief literature review and then provide information on the methodology. The theoretical framework for the study follows. The data analysis and discussion are presented afterwards. Finally, the conclusion summarises the findings of the study.

2. Perspectives on Social Transformation Campaigns in Nigeria

Social transformation campaigns have been in the foreground in Nigeria since the country attained independence in 1960. The early incursion of social transformation into the body polity of the nation can be attributed to the early entrenchment of negative practices in the country, especially among the political class. Ogbeidi (2012) confirms the duplicity of the political class in the early entrenchment of corruption in Nigeria when he says “the political leadership of the country since independence is responsible for entrenching corruption in Nigeria”. In actual fact, it was the wastefulness and abuses of office by the political class at the turn of the nation’s independence and institution of civilian rule in the first republic that the military used to justify its incursion into the nation’s politics.

However, the years after the military take-over in the bloody coup of 1966, which include the military eras of Yakuku Gowon (1966-1975) and Olusegun Obasanjo (1977-1976), were also characterised by corruption, with the exclusion of the era of Muritala Mohammed (1975-1976) (Ogbeidi, 2012). The same streak of corruption coursed through the second republic and the succeeding military regimes up to the current fourth republic (Ogbeidi, ibid.). However, since the governments themselves knew that corruption and indiscipline were prevalent in the nation, they had also at different times introduced different programmes to mobilise Nigerians for positive social transformation. Notable social transformation campaigns in Nigeria over the years have been Reconciliation, Reconstruction, and Rehabilitation, The War Against Indiscipline, Mass Mobilisation for Self Reliance, Social Justice and Economic Recovery, The National Orientation Agency (Nwankwo, Ocheni & Atakpa, 2012), and presently, Change Begins with Me.

While the above listed social transformation projects at various times were spearheaded by the government, civil society, the press, and trade unions have also contributed to social mobilisation for social transformation. Even though the efforts of various non-governmental bodies and groups were met with opposition due to the government prohibition of certain communications and its extensive control of the media, the current digital revolution has enhanced social transformation through civic engagement. Therefore, in the current fourth republic, social transformation discourse has grown astronomically in Nigeria, with citizens contributing to the discourse significantly. Opeibi (2016) remarks that this is no doubt a good development, as it has the capacity to shape not only government policies and actions but also the behavioral patterns of the citizens in general.

Research on social transformation discourse in Nigeria has also focused on the religious angle (Burgess, 2012; Rapheal, 2014; Saale, 2014), the literary angle (Ajiwe, Okwuosa & Chukwu-Okoronkwo, 2015), and the linguistic angle (Ademilokun, in press; Adedimeji, 2005; Fakuade, 2015). From the religious perspective, scholars have examined the place of prayer and the church in Nigeria’s national transformation drive, character building through religious values for national transformation, the role of charismatic Christian preaching, etc. From the literary perspective, the role of home video in engendering social transformation in Nigeria has also been studied (Ajiwe, Okwuosa & Okoronkwo, ibid.). However, the linguistic research on social transformation discourse in Nigeria, which is our concern, is rather scant. While Adedimeji (2005) and Fakuade (2015) generally carry out a sociolinguistic reflection on the place of language in social transformation, the only visible discursive work on social transformation campaigns in Nigeria is Ademilokun (in press), which analysed the discursive strategies employed by the participants in the discourse. Even though it is capable of revealing the issues around the social transformation concerns and goals of the nation, this lack of literature shows that transitivity in the discourse of social transformation in Nigeria has not received enough attention. The present study thus seeks to fill this lacuna by adopting a critical discourse-laced transitivity analysis of social transformation campaigns in Nigeria.

3. Data Sources

Data for the study comprise texts on the subject of social transformation from the government and citizens of Nigeria, mediatised in various forms. Specifically, such data addressed the themes of social transformation, such as corruption in Nigeria, democratic improprieties, gender inequality/violence, and insecurity, given the fact that they are all topical matters in the nation. The data sourced was produced by state and non-state actors. While state actors are considered as government functionaries from the President down to government parastatals (the National Orientation Agency, Ministry of Information, Nigeria Police, Independent National Electoral Commission, and the National Drug Law Enforcement Agency), non-state actors are the citizens and non-governmental organisations who seek to influence the actions of the government through their civic engagement.

The data was purposively drawn from speeches aired on television and the Internet, radio commentaries, jingles, printed texts, interviews, tweets, and comments on online newspapers and covered the period from March 2013 to March 2018. The five-year span was premised on the fact that Nigeria witnessed numerous challenges in the areas of insurgency, Fulani killings, financial misappropriation, gender-based violence, and democratic impropriety.

4. Theoretical Framework

Data analysis in this study is hinged on the transitivity system grounded in Systemic Functional Linguistics, and is further popularised by critical discourse analysis. Halliday (1985) asserts that systemic functional linguistics is anchored on the view that language is a social semiotic and projects ideational, interpersonal, and textual meanings. Halliday (1978, p. 132) states that transitivity “is the key to understand the ideational meanings of texts”. Lock (2004, p. 48) also remarks that “transitivity is the ideational dimension of the grammar of the clause and is concerned with types of processes and elements that are coded in clauses”. Transitivity is an important aspect of critical discourse analysis, which is originally grounded in Halliday’s systemic functional grammar but which critical discourse analysts also deploy in their research. In particular, Fairclough’s (2003) dialectical relational approach foregrounds the place of transitivity in critical discourse analysis. According to Machin and Mayr (2012, p. 104), whose approach to critical discourse analysis is heavily influenced by the dialectical relational approach, “Transitivity is simply the study of what people are depicted as doing and refers, broadly, to who does what to whom, and how”. Machin and Mayr (ibid.) further remark that transitivity is concerned with the agent that functions as the subject and the affected by the action of the subject which is the object.

Halliday (2004, p. 103) presents six process types in the transitivity system of English: material, mental, relational, behavioral, verbal, and existential processes. According to Halliday (2004, p. 170), the material process constructs the outer experience of a particular reality expressed in a sentence while the mental process constructs the inner experience. Machin and Mayr (2012, p. 106) further elaborate on the material process by stating that they “describe processes of doing” and that the “two key participants in material processes are the actor and the goal”. Bloor and Bloor (1995, p. 116), in describing the mental process, state that it is “not material action but phenomena best described as states of mind or psychological events” and “they tend to be realised through the use of verbs like think, know, feel, smell, hear, and see”.

Machin and Mayr (2012) remark that relational processes “encode meanings about states of being, where things are stated to exist in relation to other things” and they are expressed through verbs such as to be, become, mean, define, symbolize, represent, stand for, refer to, mark, exemplify, etc. Existential processes, according to Halliday (2004), simply indicate that something exists or has occurred. Eggins (1994) also states that such processes depict experience by saying that something is or was.

Halliday (1994) presents verbal processes as another aspect of transitivity which borders on saying. Such verbs cover all kinds of saying such as asking, arguing, telling, and stating, and non-verbal expressions such as showing and demonstrating. Behavioral processes, which represent the sixth type of process accounted for in the transitivity system, border on physiological and psychological behaviour such as dreaming, breathing, smiling, watching, etc.

In addition, transitivity accounts for the conditions in which the actions in the clause structure take place. This is captured by the concept of circumstance in the transitivity system. According to Halliday and Matthiessen (2004, p. 260), in terms of meaning, circumstance as a concept in transitivity is concerned with “circumstances associated with” or “attendant on the process” captured in a clause. Such circumstances relate to the location of an event, its time, the manner, or its cause. Therefore, the analysis of transitivity pays attention to actors, processes, and circumstances in a clause structure.

5. Data Analysis and Discussion

In this section, we carry out a qualitative analysis of purposively selected clauses in the discourse of social transformation in Nigeria. The selected clauses were manually extracted from the discourse. Specifically, we focus on the processes used by the discourse producers to address issues revolving around the social transformation concerns of Nigeria. Essentially, we, in turn, examine material processes, relational processes, and mental processes while highlighting the presentation of participants (agents) in relation to these processes.

5.1 Material Processes

According to Machin and Mayr (2012, p. 106), material processes are processes that are suggestive of doing, as there are “concrete actions that have a material result or consequence”. The data for this study contains a great deal of material processes used by the discourse participants mainly to capture the bad acts in Nigeria, to capture the good things about Nigeria, to reflect the benefits of positive actions for Nigeria, and to show how to solve the problems of Nigeria. In what follows, we examine representations of material processes in the discourse, paying attention to how they perform the above highlighted functions.

5.1.1 Material processes for negative projection of Nigeria

Since the discourse of social transformation in Nigeria is essentially about changing the negative realities in the country, it features a great deal of information about the negative realities in the nation. Given the fact that many of the negative realities being reported consist of certain doings of different actors in the nation, they are largely encoded in material processes which are concerned with actions that have material result. A few of the issues in the social transformation advocacy in Nigeria such as corruption, domestic violence, and insecurity are foregrounded through the use of material processes by the discourse participants. Let us consider some texts where material processes project negative realities in Nigeria such as corruption, gender violence, and insecurity in the discourse:

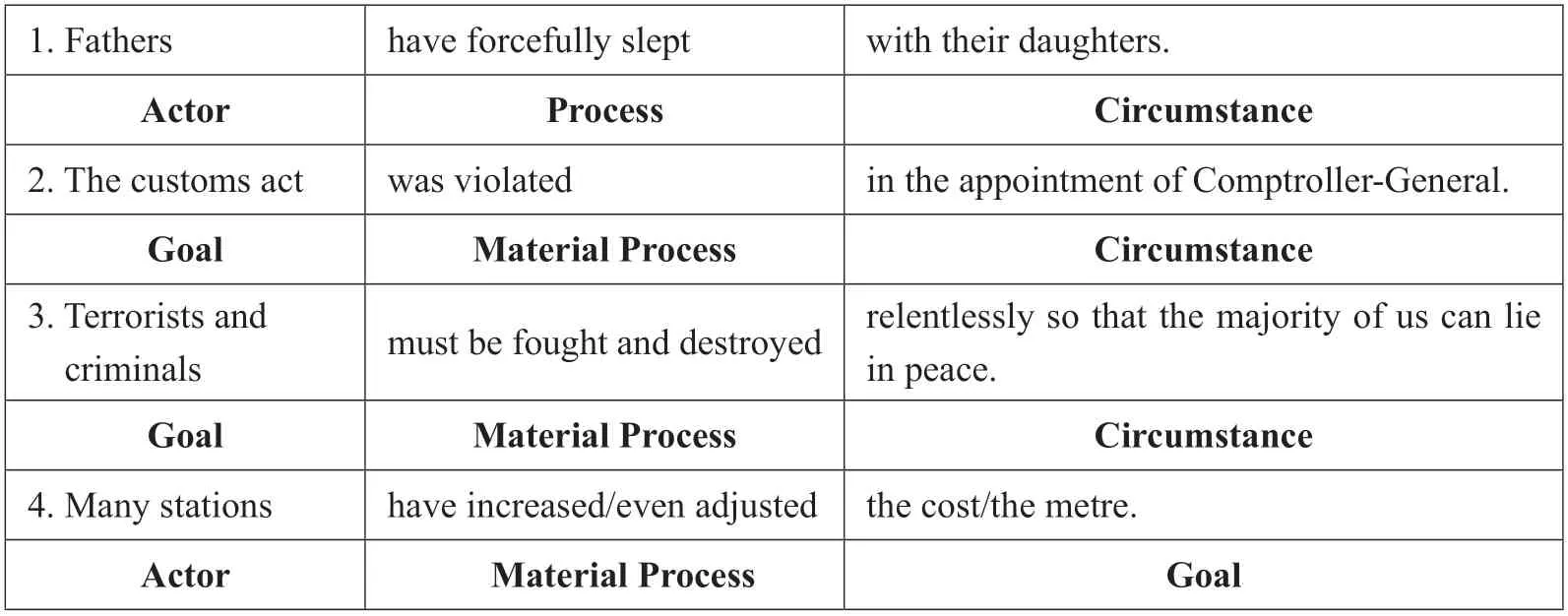

Table 1. Material processes and negative representation of Nigeria

In sentence 1 in the table above, the text producer attempts to capture the height of gender violence in Nigeria by foregrounding “Father” as someone who violates his own daughter. It is significant that in this portrayal of gender molestation, the text producer not only foregrounds the actor of the negative action but also uses an active verb in order to give force and sharpness to the unfortunate instance of gender violence in the nation. This is meant to capture the anger of women at the actions of men against them.

Sentence 2 also presents an example of the tactful use of transitivity resources to background the perpetrators of the corrupt action being reported in the sentence. Even though through the material process “was violated” and the circumstance “in the appointment of Comptroller General”, the text producer shows that he is unhappy with the level of corruption involved in the appointment procedure in the civil service, the actual perpetrators are left implicit. This is however not surprising because the text producer recognises the need to show decorum on a television interview by not mentioning names, or does not really know the exact names of such persons.

Sentence 3 also presents the use of transitivity for mapping actions that need to be taken to combat the security challenges facing Nigeria. However, even though the text producer highlights the actions to be taken against insecurity as fighting and destroying terrorists and criminals, there is nothing said about how the text producer, the President of Nigeria, hopes to achieve that. The foregrounding of the goal “terrorists and criminals” is significant, as it shows the anger of the text producer at the activities of the terrorists and criminals and the fact that he also desires to get rid of them. But then, the text producer seems to lack any coordinated method or approach of pursuing the destruction of the terrorists and criminals, as there is omission of that aspect in the text. However, a critical look at the omission of such information could also reveal the fact that the text producer might be wary of releasing such information since it is supposed to be part of the strategy to be used to combat the deadly groups. Once he mentions such a strategy in public, then he may not succeed in his bid to achieve the objective.

In sentence 4, the text producer raises the issue of corruption in the sales of petrol to the Nigerian citizenry. It can be seen that the text producer shows his anger and frustration at the corrupt process of selling fuel to Nigerians as he foregrounds the actors by making the nominal group “filling stations” occupy the initial position in the sentence. By fronting the actors, the text producer intentionally desires that readers would immediately and easily recognise the people that are responsible for the corrupt action that has been negatively affecting the generality of the people. The corruption being expressed in the sentence is indeed captured in two material processes, “have increased” and “even adjusted”, which are used to reflect the immoral actions of the fuel stations in cheating the unwary public who intend to purchase fuel. The foregrounded positioning of the actors and processes reflects Fairclough’s (2000) observation that text producers usually strive to maximise the negative representation of their adversaries. Since the filling stations have become enemies to the text producer and other Nigerians, they are given a vivid negative portrayal in the text.

5.1.2 Material processes for positive presentation of Nigeria

Even though Nigeria is generally plagued with many negative realities, there are many positive associations with Nigeria that Nigerians take pride in. Nigeria is for instance blessed with human and material resources, a positive disposition to life in spite of difficulty, and industry, among others. These features are referenced in the discourse of social transformation in Nigeria, especially through material processes, to romanticise the Nigerian past or the ideal Nigeria and to point attention to the fact that these things can be achieved in other aspects of the life of the nation or the lives of Nigerians. Let us consider the following instances of the use of material processes for romanticising Nigeria:

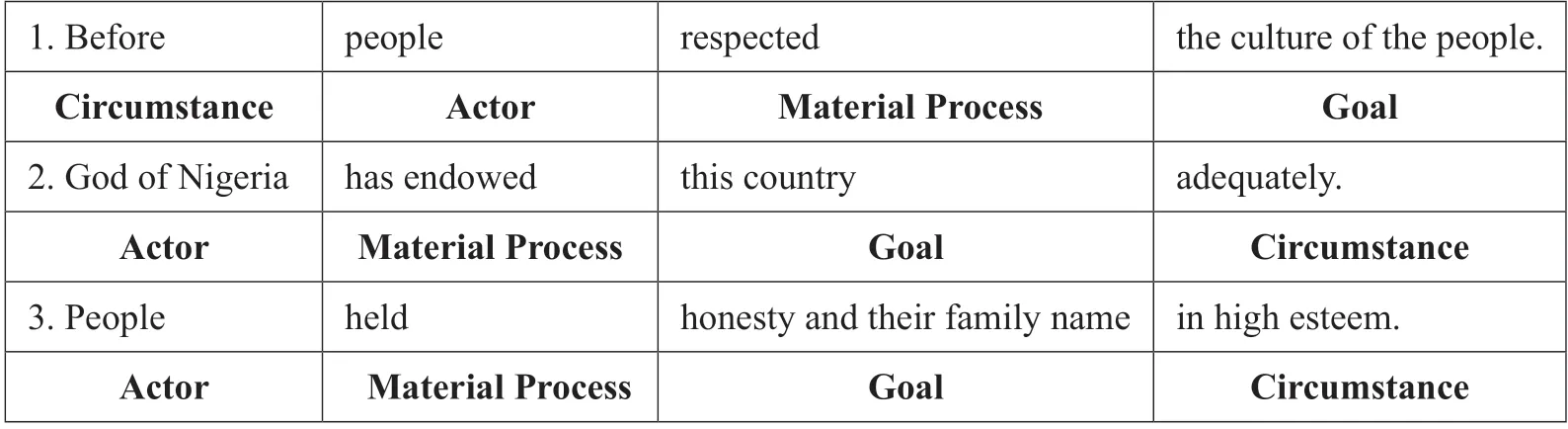

Table 2. Material processes and positive representation of Nigeria

The verbal lexeme “respected” in sentence 1 of table 2 conveys the material process used to valorise Nigeria and Nigerians, especially with respect to the past. The text producer highlights an important part of the cultures of Nigeria and Nigerians which borders on respect for people, cultural values, and practices. Such respect translated to proper conduct of people, i.e., Nigerians in different contexts. In this instance, the participants in the material process are foregrounded, as the collective noun “people” is fronted in the sentence in which it occurs. Machin and Mayr (2012) report that when certain actions portray in-group members positively, the actors are usually foregrounded, unlike when those actions portray them negatively, when they are often backgrounded.

In sentence 2, the verb “endowed” conveys the material process, presenting a good image of Nigeria as a country blessed with enormous resources. Given the religious propensity of Nigerians, one is not surprised that the actor in the sentence who performs the material process of “endowing” to the goal “Nigeria” is God. However, in spite of the primacy given to God through the positioning of the name, one realises that Nigeria still features in the subject position as the headword “God” is given the qualifier “of Nigeria”, thus marking God as supporting, or for, Nigeria. The impression is thus created that Nigeria is favoured by God and that that is why it is so richly blessed, giving the country a positive image and massaging the ego of Nigerians, especially religiously-minded ones. It is interesting that this sentence is generated by a very notable state actor, the former President of Nigeria Olusegun Obasanjo, showing that the belief in the indubitable role of God as the distributor of endowments to Nigeria has validity in Nigerian thinking and the Nigerian way of life.

The last sentence also extends the expression of the value and greatness of Nigeria, especially before contemporary times. In the sentence, the verb “held” is used to convey a material process expressing the sense that Nigerians have a strong conviction in upholding ideals of honesty in order not to soil their family name. The verb is used to praise Nigerians and to inform the world that acts of dishonesty in Nigeria are not typically Nigerian but actually influences from other cultures. It is also remarkable that since what is said about Nigeria and Nigerians in this instance is positive, the actors are foregrounded through the collective noun “people”.

5.1.3 Material processes for mapping the path to a stronger Nigeria

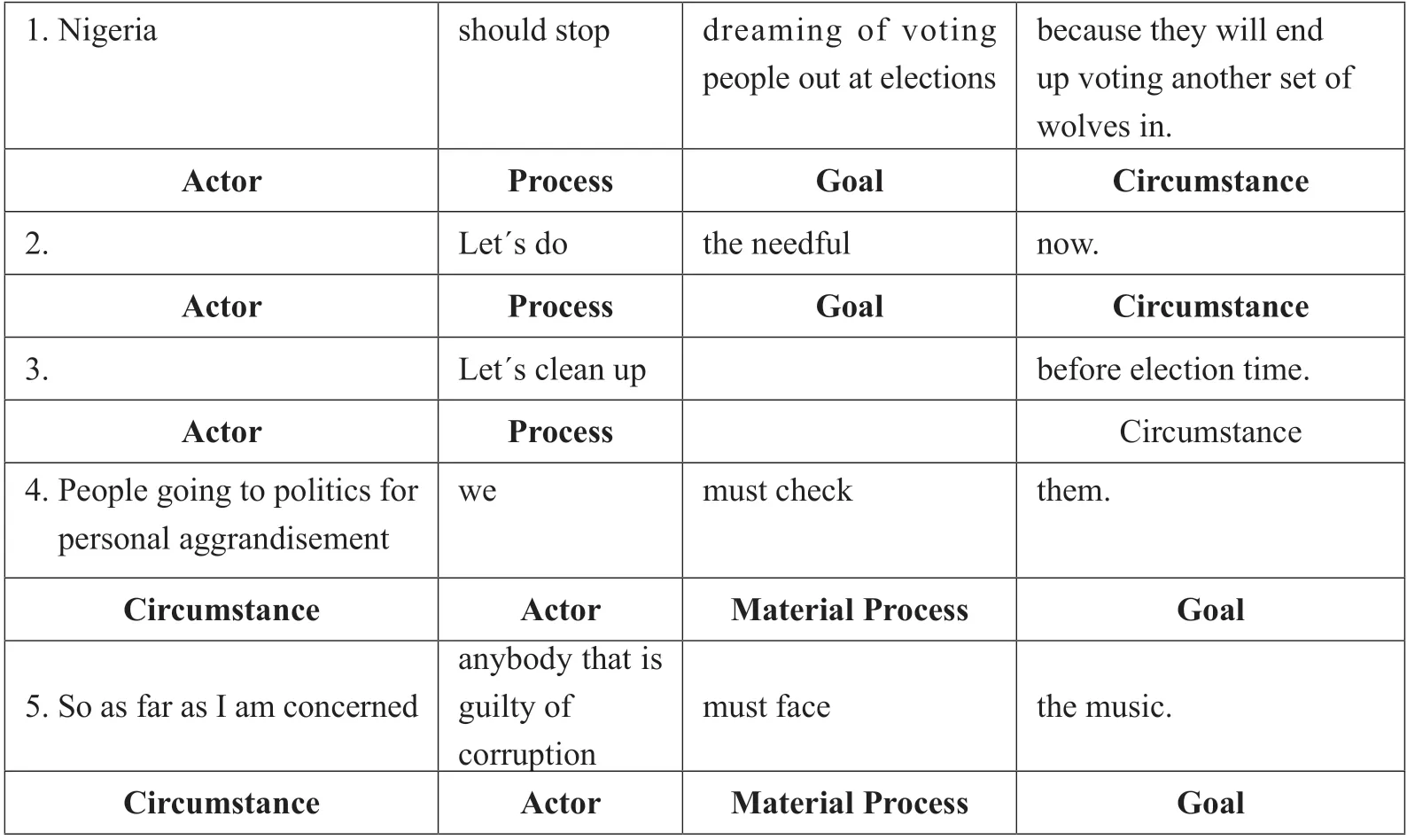

The data for this study shows that the participants in Nigeria’s discourse of social transformation also use material processes to capture the actions that can be taken or should be taken for the nation to extricate itself from its negative entanglements and progress. This is a way of road-mapping actions that are beneficial to Nigeria. Below, we present some texts that illustrate such use of material processes in the discourse:In table 3 above, there are many examples of the use of material process to register in the minds of the people how to solve some of the problems that Nigeria is experiencing. The verbs “stop”, “do”, “act”, and “clean-up” all represent material processes that show the way forward for Nigeria to change positively. For instance, in sentence 1 of the table, while Nigeria is the actor, “dreaming of voting people out at elections” is the goal. Therefore, it is considered important for Nigerians to stop viewing the current crop of political leaders as a solution to the problems of the country because these people (political leaders) are not likely to solve the problems. It is however remarkable that even though the material action of “stop dreaming” is normally humanly carried out, the text producer does not foreground Nigerians as the actor but rather foregrounds Nigeria. This strategy may be seen as an emphasis of the problems of Nigeria and the need for the nation to find a way out of its problems.

Table 3. Material processes and discursive mapping of the way forward for Nigeria

Sentences 2 and 3 “Let’s do the needful now” and “Let’s clean up before election time” are imperative sentences which are constructed in a way that the actors are not explicitly given, even though they both show certain actions that the text producers believe need to be taken in the political sense in order for Nigeria to witness positive transformation. This positive action of determination for emancipation is acknowledged by Naz, Alvi and Baseer (2012) when they remark that through transitivity, language can also be used to show power and conviction. In their analysis of transitivity in Bhutto’s political speech, “Democratization in Pakistan”, the authors remark that Bhutto’s strong commitment to re-establishing democracy in Pakistan was ably conveyed through transitivity.

In sentence 4, the verbal group “must check” is the conveyor of the material process in the sentence. The material process expressed in the sentence highlights the progress of the country. The verb “check” as used means that something must be prevented; in this case, the people going to politics for personal aggrandizement. The expression of the material process is grounded in the thinking that once the nation gets the right political leaders, the problems of the nation will be solvable. The structure of the sentence shows that the text producer is really worried about the people to be checked as they are placed as the theme of the sentence.

Sentence 5 contains a metaphorical verb “face” which is used to express the material process of what could be described as “reception”. The sense in the text is that for Nigeria to move forward, offenders should be duly punished as that would deter others from misbehaving. In actual fact, it has often been said that one major reason there are negative realities in Nigeria is that offenders get away with offences. Therefore, through the material process in the sentence, the text producer expresses the idea that Nigeria would change if due punishment is given. It is however significant in this instance that the participants in the action, i.e., the actors are foregrounded as they are placed in the subject position “anybody that is accused of corruption”. This is in line with van Dijk’s (2000) observation that out-group members that carry out negative actions are usually given prominence.

5.2 Relational processes

Relational processes are “processes that encode meanings about states of being, where things are stated to exist in relation to other things” (Machin & Mayr, 2012, p. 110). Relational processes are primarily realised through the verb “be” but can also be expressed through verbs such as “represent”, “become”, “exemplify”, “stand for”, “mean”, “symbolise”, etc. The discourse of Nigeria’s social transformation advocacy is replete with relational processes owing to the fact that the discourse is characterised by depiction of the state of Nigeria, which is in tandem with the concern of relational processes. Relational processes, for instance, are used by the participants in the discourse most remarkably to show how bad things are in Nigeria and to construct a negative image for Nigerian leaders. Below, we elucidate the various uses of relational processes in the discourse.

5.2.1 Relational processes for negative representations of Nigeria

A great deal of the negative realities in Nigeria are captured by participants in Nigeria’s social transformation discourse through relational processes. Below we present texts containing relational processes that reflect the negative state of affairs in Nigeria:

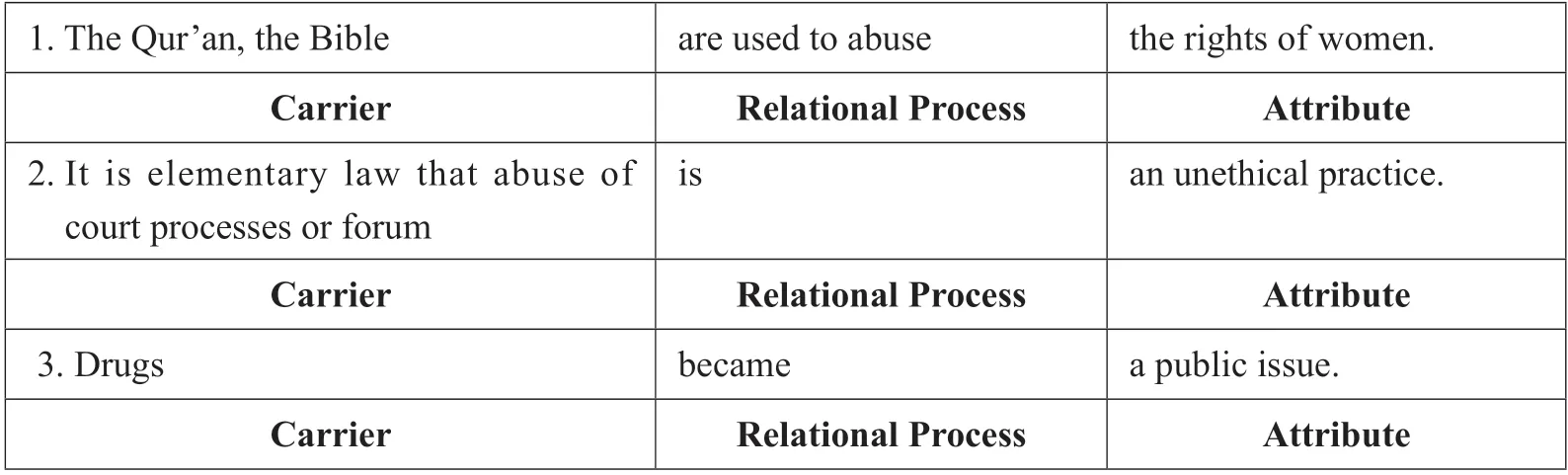

Table 4. Relational processes and negative depictions of Nigeria

Sentence 1 contains the use of relational process to capture another negative reality in Nigeria bordering on gender inequality and discrimination due to the patriarchal nature of the cultures in the country. However, this reality, which subjects women to some inhuman treatment, is supported by some religious proclamations in Nigerian society. So, the text producer presents this fact about Nigeria by associating the Qur’an and the Bible with the oppression of women. While the position of the text producer may be said to be a bit strong, there is at least the implication that the manipulation of the two scriptures is responsible for the oppression of women in Nigeria through the relational process.

The second sentence contains the verb “is” as the conveyer of the relational process in the sentence. The text producer deploys the relational process to associate a common negative reality in the country, actions bordering on the abuse of court processes, with “unethical practice”, which the people should stay away from in Nigeria. Through the relational process, the text producer sheds light on the negative state of affairs in Nigeria. The last text, however, showcases the use of a verb other than “be” as the conveyer of the relational process in the sentence. Through the use of the verb “became”, the text producer associates “drugs” with Nigeria, as the verb “became” shows that the phenomenon of drug use is a major part of the negative realities in the nation.

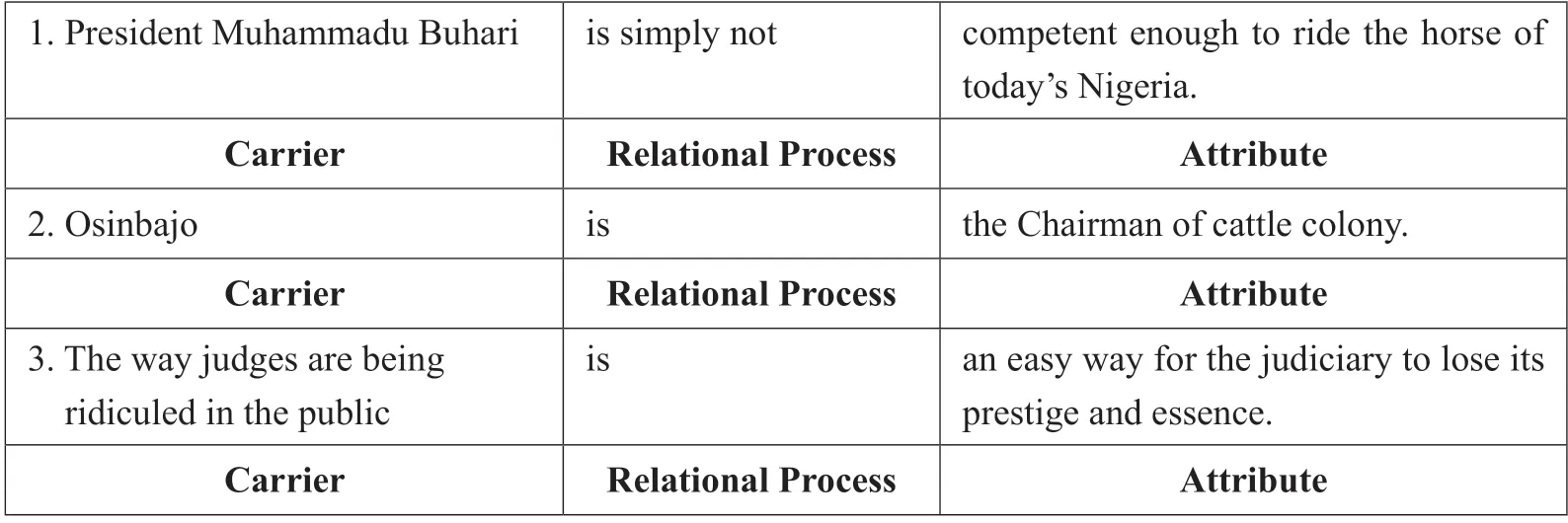

5.2.2 Relational processes for negative construction of Nigerian leaders

The discourse also shows that participants comment on the personalities of the political leaders of Nigeria, mainly showing their features which have impacted negatively on the national life of the country. This trend is no doubt in tandem with the popular belief among Nigerians that the problem of Nigeria mainly inheres in the kind of political leaders that the country has. Let us consider the following texts in which such construction manifests:

Table 5. Relational processes and negative presentation of Nigerian leaders

The texts above are typical examples of how non-state actors construct negative images for top political leaders in the country. In the first sentence for instance, through the use of the verb “is”, the text producer uses the relational process to equate President Buhari with incompetence as Nigeria’s President. In view of the many negative developments in Nigeria, people have been questioning the competence of the president. This is what the text producer captures through the relational process in the sentence. In the second sentence, there is also the use of the relational process for the negative construction of Nigerian political leaders - in this instance, the Vice-President of Nigeria, Professor Yemi Osinbajo. Here, Prof. Osinbajo is associated with the negative issue of cattle colonies which arose from the lingering clashes between farmers and herders in Nigeria over the destruction of farmlands by cattle as a result of the entrenchment of open grazing across the country. The support given by Prof. Osinbajo to the herders thus portrayed him as an insincere person who is pursuing an agenda that is not beneficial to the people just because he wants to maintain his positive standing in the sight of the President who is seen as tacitly protecting the interest of the herders. For the Vice President to be associated with the cattle colony matter gives the state actor a rather negative image in view of the fact that the matter is a sensitive one that most Nigerians are displeased with. The uses of relational processes for the negative depiction of Nigerian leaders aligns with Opara’s (2012) observation, in his analysis of transitivity in narrative discourse, that through transitivity, we can infer how a text producer wants us to view a particular character.

The last sentence is an example of the use of relational process to associate judges in Nigeria with inappropriate behaviour. The verbal expression “are being” serves as the conveyer of the relational process which links judges with ridicule in society. Such a negative construction of judges, who are supposed to be the administrators of justice in Nigerian society, depicts a gloomy picture of Nigeria. If the custodians of justice and law have become so dishonorable that they are subjected to ridicule at ease, then the entire nation must be enveloped with inappropriate behaviour.

5.3 Mental processes

According to Machin and Mayr (2012, p. 107), “mental processes are processes of sensing and can be divided into three classes: ‘cognition’ (verbs of thinking, knowing, or understanding), ‘affection’ (verbs of liking, disliking, or fearing), and ‘perception’ (verbs of seeing, hearing, or perceiving)”. The data for this study reveals that mental processes are used by the participants in Nigeria’s discourse of social transformation for the expression of their views on issues relating to Nigeria and to capture the senses of Nigerians. Below we examine such uses of mental processes in the discourse, using excerpts for illustration rather than tables in order to provide sufficient context for a clear appreciation of the mental processes.

5.3.1 Mental processes for the expression of views of discourse participants

There are significant instances of discourse participants using mental processes to express their views on the situation in Nigeria. Below we present examples of such deployment for mental processes:

We should ask ourselves, what are the fundamental causes of corruption? And I (senser) / think (process) the government should engage social scientists(phenomenon).

NSA Interview

Rubbish,I (senser) know (process)Ekiti will not be a victim of this (of cattle colony) in Jesus name(phenomenon).

NSA Comment

I need not mention the serious effort we have engaged in since the inception of this administration on the fight against corruption in our public life. With the progress we have so far made in that regard, we(senser) feel (process)the need to ensure that we put in place the necessary sustainable framework for action and measures that will help to entrench and consolidate the progress achieved so far(phenomenon).

SA Speech

Illicit drug use is a challenge in Nigeria andI (senser) believe(process)in our centres across the federation we have 36 state commands and in each of these commands, we have counseling departments for counseling and then we do treatment in conjunction with the general hospitals and psychiatric hospitals(phenomenon).

SA Jingle

The texts above demonstrate how the participants in the discourse use mental processes to express their views on various issues regarding Nigeria. In the first text, the verb “think” is used by the text producer to convey the mental process expressed in the sentence. The verb is strategically deployed to make the suggestion of the text producer appear well informed and acceptable to the government and the public. By using the verb “think”, the text producer represents his idea of the need to engage social scientists to explain the prevalence of corruption in Nigeria as carefully thought out. Such a representation is meant to enhance the value of the proposition and thus make people accept it. Therefore, even though the word is common, it serves the strategic function of adding significance to the idea of the text producer. This kind of mental process is what van Leeuwen (2008) refers to as a reaction. It can be seen as a reaction because the choice of the verb “think” by the text producer is motivated by the gravity of corruption in Nigeria.

The second text also features a mental process that can be categorised as a process of reaction using van Leeuwen’s (2008) approach. The verb “know” is used for the expression of the rejection of the proposal for cattle colonies by the President of Nigeria to favour his kinsmen, who are mainly involved in cattle rearing. The mental process shows that the rejection, which of course is a reaction, is strongly in tandem with the choice of the use of the word “rubbish” at the beginning of the sentence. The use of such mental process can also be seen as manipulative in the sense that such strong disapproval of the idea might influence the judgment of other participants in the discourse or members of the community, or even members of the Christian community, since there is a reference to Jesus Christ.

In the last two texts, mental processes are used for the expression of the views of the text producers about the different issues in context. In the first text for instance, there is the use of the verb “feel” which marks the reaction of the speaker, the President, to what he considers a milestone in the campaign for social change in Nigeria. The use of the verb “feel” can be seen as manipulative in the sense that the speaker, being a politician, wants to appeal to the public as someone who is delivering. The use of “believe” in the second text, however, can be seen as a hedge used to lessen the commitment of the text producer to the truth of the information he provides in the text. Being an officer of the drug enforcement agency, the text producer should be able to state categorically the services and facilities available in their offices across the nation, but he rather dodges such a commitment by using the verb “believe”. Such use of mental process reveals the insincerity and inadequacy of the government and even government actors in Nigeria, which is even part of the matters that the civic engagement of Nigerians border on.

5.3.2 Mental processes for conveying the perceptions of Nigerians on social issues

Apart from serving to highlight the senses of the discourse participants regarding diverse issues in Nigeria, the discourse of social transformation in the country is also characterised by the use of mental processes. Below are examples of the use of mental processes in the discourse to frame the perspectives of Nigerians on matters of concern in their country:

We (senser)alwaysthink (process)it is the poor women (phenomenon). It’s not. In fact, the poor woman can stand up for it.

NSA Interview

The whole world(senser) knew (process)that Fulani terrorist herdsmen killers killed thousands and continue the killing(phenomenon).

NSA Newspaper Comment

It is amazing to see employers of labour to ask for forms of inducement from job-seekers before they are employed. This act has crept into the education sector and it isbelieved (process)to have contributed to the rot in the system(phenomenon).

SA Radio Commentary

Experts(senser) believe (process)that it is a collective responsibility for all Nigerians to work towards the path to build a morally regenerated society(phenomenon).

SA Radio Commentary

The verbs “think” and “knew” foregrounded in the first two texts are the carriers of mental process in each text. For instance, in the first text, “think” qualifies as an example of van Leeuwen’s (2008) mental process of reaction because the verb is used to react to the general assumption of Nigerians about women in abusive marriages. The use of the verb is meant to index the psychology of many Nigerians regarding women. The verb “knew” in the second is used for the purpose of marking assertion and conditioning the audience or hearers to accept the opinion of the text producer. The use of the verb is manipulative as it is deployed to make the readers accept the information conveyed in the sentence and thus reject the Fulani people of Nigeria. Evidence for the manipulative nature of the mental process is the hyperbolic content of the text where it is said that the Fulani people had killed thousands. Since the text is produced in the context of recent Fulani attacks over cattle grazing, one is certain that there are indeed no records showing that the Fulani have killed thousands as alleged.

The last two texts illustrate the use of the verb “believe” to capture the perspectives of Nigerians on corruption and moral debasement in Nigeria respectively. The use of the verb in both texts is quite similar as it is used to present the opinions of Nigeria in a less assertive way, because the verb “believe” serves to hedge the ideas in the sentences. For instance, in text one, the verb is used to hedge the proposition that the reality of inducement has contributed to the rot in Nigeria’s educational system. It is, however, remarkable that the hedge of the proposition in the sentence through the verb contradicts the assertiveness with which the text producer stated that inducement exists in the education system. Since the text producer is certain that such a negative phenomenon exists in this system, it is certain that the education system would be compromised. The carefulness of the text producer which manifests in the hedging of the text also reflects in the passivisation of the verb in the text. Rather than say “Nigerians believe”, the text producer says “it is believed”, which even further weakens the content of the expression. Therefore, the hedging of the proposition through the use of the verb “believe” can be said to be an attempt at political correctness on the part of the text producer, or an instance of inadequate thoughtfulness. Similarly, in the second text, the verb “believe” is used to hedge the proposition in the sentence containing the verb that every Nigerian has the responsibility to contribute to the construction of a morally sound Nigeria. However, in this instance, the verb is in the active form, thus making it stronger than the former.

The use of mental processes in the discourse—which of course is the least significant, as in many other studies on transitivity such as Adjei, Ewusa-Mensah and Okoh (2015)—shows that the discourse participants are more interested in actions than promises, as in the case in the 2009 speech on the state of the nation by Atah Mills studied by Adjei, Ewusa-Mensah and Okoh (ibid.). The few instances of mental processes in the discourse of social transformation are informed by the fact that, apart from Nigerians being eager to witness concrete actions taken with respect to the condition of Nigeria, they are also emotional about the level of degeneration in the nation, which makes them pensive and thus use mental processes.

6. Conclusion

This essay has focused on the analysis of the transitivity choices for conveying critical meanings bordering on ideology, power, and manipulation in the discourse of social transformation in Nigeria. Using the system of transitivity as given by Halliday in the systemic functional linguistics and appropriated for critical discourse analysis by Fairclough (2013) and Machin and Mayr (2012), the essay attempted to show the transitivity choices that characterise the discourse.

The study shows that prominent transitivity choices that are strategically deployed to convey crucial meanings in the discourse are material processes, relational processes, and mental processes. Material processes represent the most prominent transitivity choice in the discourse, showing the fact that the participants focus much on the actions that have undermined the development of their country and those that are needed for the nation to experience the real development that it seeks. Material processes are used to show the negative condition of Nigeria, to construct Nigeria positively, especially the Nigerian past which is reflected in the tense, and to map out the actions that need to be taken for Nigeria to grow into a strong country. Relational processes are also deployed for the negative representation of Nigeria and Nigerian leaders while mental processes are deployed to highlight the perceptions of participants in the discourse, and Nigerians generally, on different issues relating to social transformation in Nigeria. The study concludes that transitivity plays a central role in foregrounding social problems in the discourse of social transformation in Nigeria as well as a means for engendering social participation in the transformation agenda.

杂志排行

Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- Umwelt-Semiosis: A Semiotic Perspective on the Dynamicity of Intercultural Communication Process

- Towards Semiotics of Art in Record of Music

- Deducing the Intonation of Chinese Characters in Suzhou-Zhongzhou Dialect by Its Singing Technique in Kunqu: A New Probe into Ancient Chinese Phonology

- Teaching Indigenous Knowledge System to Revitalize and Maintain Vulnerable Aspects of Indigenous Nigerian Languages’ Vocabulary: The Igbo Language Example

- A Statistical Approach to Annotation in the English Translation of Chinese Classics: A Case Study of the Four English Versions of Fushengliuji1

- L3 French Conceptual Transfer in the Acquisition of L2 English Motion Events among Native Chinese Speakers