Comprehensive review into the challenges of gastrointestinal tumors in the Gulf and Levant countries

2020-05-14

Fadi Farhat, Hammoud Hospital UMC, Saida PO Box 652, Lebanon

Abdulaziz Al Farsi, Bassim Al Bahrani, Medical Oncology Department, Royal Hospital, Muscat PO Box 1331, Oman

Ahmed Mohieldin, Medical Oncology Department, Kuwait Cancer Control Center, Kuwait PO Box 42262, Kuwait

Eman Sbaity, Division of General Surgery, American University of Beirut, Beirut 1107 2180,Lebanon

Hassan Jaffar, Oncology Department, Tawam Hospital, Al Ain PO Box 15258, United Arab Emirates

Joseph Kattan, Hemato-oncology Department, Hotel Dieu de France, Beirut, Lebanon

Kakil Rasul, Hemato-oncology Department, National Center for Cancer Care and Research,Doha, Qatar

Khairallah Saad, Pathology Department, Institute National de Pathologic, Beirut, Lebanon

Tarek Assi, Oncology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Saint-Joseph University, Beirut,Lebanon

Waleed El Morsi, Pfizer Oncology-Emerging Markets, Dubai Media City, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Rafid A Abood, Oncology Department, Basra College of Medicine, Basra, Iraq

Abstract

Although gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are rare, with an incidence of 1/100000 per year, they are the most common sarcomas in the peritoneal cavity.Despite considerable progress in the diagnosis and treatment of GIST, about half of all patients are estimated to experience recurrence. With only two drugs,sunitinib and regorafenib, approved by the Food and Drug Administration,selecting treatment options after imatinib failure and coordinating multidisciplinary care remain challenging. In addition, physicians across the Middle East face some additional and unique challenges such as lack of published local data from clinical trials, national disease registries and regional scientific research, limited access to treatment, lack of standardization of care,and limited access to mutational analysis. Although global guidelines set a framework for the management of GIST, there are no standard local guidelines to guide clinical practice in a resource-limited environment. Therefore, a group of 11 experienced medical oncologists from across the Gulf and Levant region, part of the Rare Tumors Gastrointestinal Group, met over a period of one year to conduct a narrative review of the management of GIST and to describe regional challenges and gaps in patient management as an essential step to proposing local clinical practice recommendations.

Key words: Gastrointestinal stromal tumors; Diagnosis; Disease management; Treatment;Challenges; Middle East

BACKGROUND

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are rare, with an incidence of 1/100000 per year[1]; nonetheless, they are the most common mesenchymal tumors of the GI tract[2].Epidemiological data concerning GIST in the Gulf and Levant countries is scarce, with several studies describing cases within the region, including Kuwait[3], Qatar[4], Saudi Arabia[5]and Lebanon[6]. GIST is the most common sarcoma in the peritoneal cavity,and metastatic spread can be found in extravisceral locations such as the omentum,mesentery, and retroperitoneum[7,8]. Clinical signs and symptoms depend on the tumor’s location and size, with GI bleeding the most common symptom, followed by abdominal discomfort, pain, abdominal distention, and weight loss[7]. Small,asymptomatic, indolent GISTs are discovered incidentally, whereas highly malignant GISTs are typically large and symptomatic at the time of diagnosis[7].

In the past, malignant GISTs were misdiagnosed mainly as leiomyosarcomas, and were considered one of the tumor types most refractory to conventional chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy[2]. However, the development of imatinib led to a paradigm shift in the management of metastatic GIST, and imatinib became the treatment of choice in the metastatic setting, later being used in earlier stages[2]. Given the success with surgery and targeted therapy, it is estimated that the prevalence of GIST is likely to be 10 times that of the reported incidence, with the number of GIST survivors approaching 135-155 per million per year[2].

RATIONALE AND APPROACH

Despite the progress in treatment strategies, about half of all GIST patients will experience disease recurrence[9]. With only two drugs - sunitinib and regorafenib –approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for GIST after imatinib failure,managing patients with primary and secondary resistance or those with refractory disease poses a huge challenge[9]. Moreover, appropriate GIST management requires a multidisciplinary approach, as the correct characterization of the tumor at diagnosis requires a specialized endoscopist, radiologist, and nuclear medicine physician, with treatment potentially involving a surgeon and a clinical oncologist[10].

Patients and physicians across the Middle East face additional unique challenges,including the lack of published epidemiological data resulting in limited knowledge about unique disease features and molecular patterns. Challenges related to drug availability, lack of standardization of care, and limited access to mutational analysis further impede appropriate GIST management across the region.

Although global guidelines set a framework for management, there are no local practice guidelines that meet the practical needs of regional physicians in a resourcelimited environment. A consensus on the diagnosis and management of GIST tumors for the Gulf and Levant countries is necessary to improve health education, diagnostic capabilities, patient identification and screening, treatment access, and disease monitoring. Such guidelines would reiterate the need for local clinical trials to generate data to help benchmark local disease biology and genetics relative to published global data.

Therefore, a group of 11 experienced medical oncologists practicing across the Gulf and Levant region created the Rare Tumors GI Group. Through a series of short meetings conducted over a period of 1 year (2016-2017), the Rare Tumors GI Group drafted a narrative review and placing this in the context of the local challenges could highlight the need to standardize care across the region. This paper aims to review current practices in the region and describe regional GIST management challenges; in preparation for proposing local clinical practice recommendations.

CLINICOPATHOLOGICAL FEATURES

Clinical features

GIST includes tumors with a wide biological spectrum at all sites of occurrence, with diverse patterns including nodular, cystic, and diverticular tumors[11]. GISTs are commonly seen in patients > 50 years of age[12]. GISTs are most commonly located in the stomach (60%-70%), followed by the duodenum (20%-25%), the anus and rectum(5%), and the esophagus and colon (< 5%)[7]. They are predominantly seen in women[1]. Signs and symptoms of GIST depend on the anatomic location and size of the tumor, with GI bleeding being the most common clinical manifestation. Pain due to tumor rupture, GI obstruction, or appendicitis can occur[11]. GIST commonly metastasizes to the abdominal cavity and the liver; uncommonly to the lymph nodes and lungs; and rarely to the bones, soft tissue, and skin[11].

Histopathological description

Microscopic features of GIST tumors depend on the site. They may be cellular or hypocellular, with most being spindle-cell tumors (70%-80%) and a minority being epithelioid or mixed spindle, epithelioid (20%-30%); or, rarely, pleomorphic[7,11,12].GIST tumors may have prominent vascularity[7].

Immunohistochemistry

GIST tumors are immunohistochemically positive for KIT [cluster of differentiation(CD)117] (94.7%) and Discovered on GIST-1 (DOG1) (94.7%), and about 70%-80% coexpress CD34[7,12]. GISTs may be positive for smooth-muscle actin (30%-40%), and rarely for S100 protein (5%), desmin and keratin (1%-2%)[12,13].

Molecular pathology

The clinicopathologic heterogeneity of GIST is associated with its molecular diversity,with the majority being spontaneous activating mutations inKIT(approximately 78.5%), and sometimesPDGFRA(5%-10%)[14]. About 10%-15% of GISTs do not harborKIT/PDGFRAmutations and are known as wild type[13,15]. Given that the treatment of GIST depends on the mutations present, genotyping is integral to GIST management[16].

DIAGNOSIS

Tissue biopsy

For tumors suspected to be GIST, biopsy is necessary to confirm diagnosis for surgical planning and initiating tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy[7,12]. For tumors < 2 cm detected within the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum, excision is necessary to make a histological diagnosis, as endoscopic biopsy is difficult[1]. As the majority of GIST tumors < 2 cm are likely to be low risk, the standard approach includes endoscopic ultrasound assessment and follow-up, with further excision only for patients with growing or symptomatic tumors[1]. Endoscopic ultrasound is preferred over percutaneous biopsies due to potential intraperitoneal tumor spillage with the latter[7].

Tumors ≥ 2 cm in size are at a high risk of progression and biopsy excision is standard practice[1,13]. Multivisceral resection using multiple-core needle biopsies and endoscopic ultrasound guidance or an ultrasound-/computed tomography (CT)-guided percutaneous method is a common approach[1]. For patients presenting with metastatic disease, laparotomy for diagnostic purposes may not be necessary and a biopsy of the metastatic focus is sufficient[1].

Radiological findings

Plain abdominal imaging:Plain abdominal imaging is not specific for GIST diagnosis. Barium studies can suggest GIST by detecting a filling defect that is sharply demarcated and elevated compared with the surrounding mucosa[17].

Ultrasonography:Abdominal ultrasonography, although not optimal for GIST diagnosis, can evaluate liver involvement and the presence of tumor necrosis.Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is useful for characterizing and assessing localization of lesions, especially < 2 cm[18].

Computed tomography scanning of the abdomen and pelvis:CT is the method of choice for diagnosing and staging GISTs[19]. It provides comprehensive information regarding tumor size and multiplicity, presence of calcifications, irregular margins,ulcerations, heterogeneity, regional lymphadenopathy, evidence of extraluminal and mesenteric fat infiltration, location, and relationship to adjacent structures[20].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI):MRI provides similar information to CT but is more accurate in identifying rectal GISTs and liver metastasis, hemorrhage, and necrosis[18].

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning with 2-(F-18)-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose:PET scanning with 2-(F-18)-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose can be used as an adjunct to CT scanning for preoperative staging work-up, to distinguish viable lesions from necrotic tissue, benign from malignant tissue, and scar tissue from recurrent tumor. PET scanning facilitates monitoring of early clinical responses to neoadjuvant therapies and identification of early recurrence[21].

Mutational analysis

In addition to tumor location, morphology, and immunohistochemistry, mutational analyses ofKITandPDGFRAgenes are important for diagnosis[13]. About 80% of GIST tumors have an oncogenic mutation in the KIT tyrosine kinase domain, mostly encoded byKITexon 11, although some occur in exons 9, 13, and 17[13]. A subset of GIST tumors typically demonstrating an epithelioid morphology and expressing little or no KIT may also have an activating mutation in the KIT-homologous tyrosine kinase PDGFRA but this can only be determined through molecular analysis[13]. An estimated 5%-7.5% of GIST tumors, predominantly in the stomach, harbor the PDGFRA mutation, with two-thirds of these having the PDGFRA D842V mutation[22].

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) strongly recommends undertaking mutational analysis, especially if imatinib therapy is required for unresectable or metastatic disease or in patients with primary disease, particularly for high-risk tumors[13]. The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) recommends mutational analysis as standard practice in diagnostic work-up of all GISTs due to its prognostic value and ability to predict sensitivity to therapy[1].

Risk stratification

Risk classification systems have been developed and validated to predict the probability of postoperative relapse, including the National Institutes of Health (NIH)consensus classification (Fletcher’s criteria), Armed Forces Institute of Pathology criteria (Miettinen’s criteria), the “modified NIH” classification (Joensuu’s criteria),and the modified Fletcher risk classification[23-26].

Stratifying GISTs into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk categories is preferred to classification into benign or malignant, as a small number of GISTs with a histologically benign appearance may recur or metastasize[12]. Such categorization helps select patients for adjuvant imatinib therapy[26]. Unlike other classification systems, the “modified NIH” classification includes “tumor rupture”, a prognostic indicator for predicting the benefit of further treatment with adjuvant imatinib therapy[27].

Tumor size and mitotic index are important prognostic features in risk stratification[13]. Assuming that all GISTs have malignant potential, Miettinen and colleagues demonstrated that the anatomic location of the tumor affects the risk of recurrence and progression[13].

TREATMENT

Management of primary, localized GIST

Surgery:Complete surgical resection with negative margins, without causing tumor rupture and with economic resection of the underlying organ, is the mainstay curative treatment for localized GIST[1,28]. This is feasible due to the exophytic growth pattern of these tumors. Negative margins can be easily achieved with organ-sparing segmental or wedge resections of the organ[23,28,29]. Furthermore, as lymphatic spread of the tumor is rare and lymph node dissection is generally not necessary, complete surgical resection can be achieved without sacrificing organ function[23,27,29].

Potential complications of surgery, especially for large tumors, include intraoperative bleeding and tumor rupture, resulting in spillage of tumoral contents into the peritoneal cavity[24,28].

Role of laparoscopic surgery:Surgeons have increasingly adopted a minimally invasive surgical approach. Evidence suggests that, in select patients, endoscopic or laparoscopic removal of GISTs yields recurrence rates comparable to open resection,improves long-term survival and enables better short-term postoperative outcomes[24,29,30].

The technical feasibility of performing an oncologically safe and effective laparoscopic or endoscopic procedure, without risk of rupture or incomplete removal,should be predetermined based on preoperative tumor evaluation[24,29,30]. The stomach is the only organ where either laparoscopic or endoscopic procedures can be performed safely and reliably in well-selected patients[29].

Although complete surgical resection of localized GISTs is successful in approximately 95% of cases, relapse affects approximately 40% of patients,particularly within the first 5 years after surgery[25,30-32]. The liver and peritoneum are the most common sites of recurrence[32]. Estimating tumor prognosis and the risk of postoperative recurrence is essential to tailoring patient management[23,25,26].

Imatinib adjuvant therapy:Depending on the risk of recurrence following complete surgical resection, adjuvant therapy should be initiated[33]. Traditional chemotherapy and radiotherapy are ineffective against GISTs[34,35]. Molecular targeted therapies, such as TKIs imatinib, sunitinib, and regorafenib have gained approval by the FDA for treatment of GIST[27,36]. Imatinib is an oral, selective TKI that inhibits KIT and PDGFRA, preventing tumor proliferation. It is regarded as the primary adjuvant treatment for postoperative GIST patients with a high risk of recurrence and is generally well tolerated[28,31,35].

Several clinical trials have confirmed the clinical benefits and acceptable safety profile of imatinib adjuvant treatment in surgically resected GIST patients with substantial risk of relapse. A randomized placebo-controlled study evaluated the impact of 1-year adjuvant imatinib therapy (400 mg daily) in patients with primary,localized, KIT-positive GIST (> 3 cm) who had undergone gross surgical excision and had low, intermediate, or high risk of recurrence. A significant difference was observed in the 1-year recurrence-free survival (RFS) rates (imatinib 98%vsplacebo 83%) but not for overall survival (OS)[37].

The efficacy of 2-year imatinib adjuvant therapy (400 mg daily) was investigated in surgically resected, KIT-positive GIST patients showing high or intermediate risk of recurrence. The 3-year RFS rates were higher in the adjuvant imatinib group (84%)vsplacebo (66%), with no impact on survival outcomes[38].

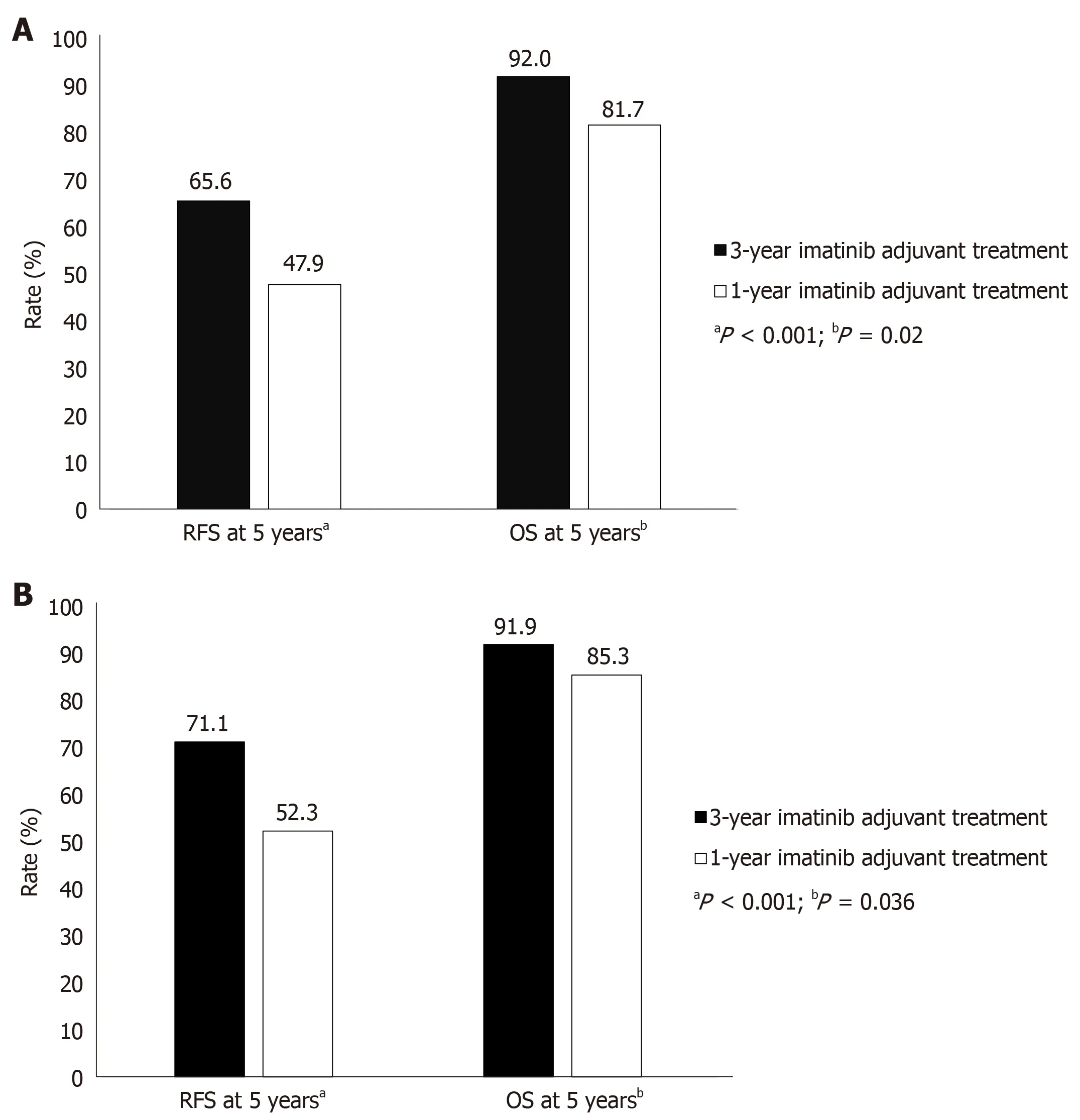

A further trial demonstrated the efficacy of 3-year imatinib adjuvant treatment in GIST patients who had undergone tumor resection and had high risk of recurrence.At a median follow-up of 54 mo, 5-year RFS and OS were significantly greater in imatinib patients treated for 3 yearsvs1 year (Figure 1A), with acceptable tolerability[39]. In a subset of patients with centrally confirmed GIST and without macroscopic metastases at study entry, with a median follow-up of 90 mo, 3-year treatment resulted in significantly higher RFS and OS than did 1-year treatment(Figure 1B)[40].

Therefore, adjuvant imatinib therapy in postoperative high-risk GIST patients improves RFS, with an acceptable tolerability profile. Length of imatinib treatment influences treatment response, with greater survival with 3 years of treatmentvs1 year. Therefore, 3-year adjuvant imatinib treatment is recommended to improve RFS and OS in high-risk GIST patients who have undergone complete surgical resection of the primary localized tumor[1,23,27].

Controversies surrounding the optimal treatment duration and its role in patients with intermediate risk continue[1,25,27,35]. As there are insufficient data available and a 10% risk of relapse, a standard recommendation cannot be made. A shared decision with the patients regarding adjuvant therapy is necessary for intermediate-risk patients[39].

Whilst the current standard of practice is 3-year adjuvant imatinib therapy in highrisk patients, further investigation of longer treatment duration and outcomes is ongoing. The PERSIST-5 trial, in high-risk GIST patients, demonstrated that 5-year adjuvant imatinib treatment achieves 5-year RFS and OS in 90% and 95% of patients,respectively, with an acceptable tolerability profile[41]. Further ongoing clinical trials aim to compare the efficacy and safety of 5- and 6-year adjuvant imatinib treatment with additional 3-year treatment in high-risk GIST patients, and the results will likely affect treatment recommendations[25].

The efficacy of imatinib varies withKIT/PDGFRAmutation type[25]. Clinical data suggest that adjuvant imatinib treatment improves RFS in GIST patients with deletions inKITexon 11, but not in patients with some mutations inKITexon 11 or 9[42,43]. Despite the absence of data in adjuvant studies, dose escalation up to 800 mg,instead of the standard 400 mg dose, could be beneficial in patients withKITexon 9 mutations[1,34]. Furthermore, adjuvant imatinib treatment is not recommended in patients with thePDGFRAD842V mutation or those with GIST WT, as treatment is ineffective[1,25,27]. Therefore, in addition to the assessment of postoperative recurrence risk, mutation analysis should part of the decision-making process prior to imatinib adjuvant therapy initiation, as recommended by the ESMO and EUROCAN[1,27,33].

If tumor rupture, an unfavorable prognostic factor, occurs before or during surgery,adjuvant imatinib therapy should be initiated due to the high risk of peritoneal relapse, which has significant impact on progression-free survival (PFS)[44]. Patients with gastric GIST withKITexon 11 mutation (codon 557 and 558) are at increased risk of tumor rupture[44]. The optimal duration of treatment in these cases remains undetermined[1].

Imatinib neoadjuvant therapy for localized GIST:Neoadjuvant imatinib should be considered in patients with initially unresectable or borderline resectable bulky tumors. A prospective phase 2 trial evaluated an 8-12 wk short course of 600 mg neoadjuvant imatinib in 63 GIST KIT+ or recurrent resectable tumors[45]. The estimated 5-year PFS and OS rates for localized disease were 55% and 77%, respectively, with only 7% achieving a partial remission (PR)[45]. A multinational phase 2 study involving patients with gastric GISTs ≥ 10 cm demonstrated that neoadjuvant imatinib therapy(400 mg once daily) for 6-9 mo allowed a substantial proportion of patients to undergo R0 surgery (90%)[46]. Furthermore, 2-year PFS and OS rates of 89% and 98%were achieved, respectively, over a median follow-up of 32 mo[46].

Based on the encouraging findings from clinical studies, neoadjuvant imatinib treatment is indicated if reducing the tumor bulk prior to surgery would permit lessmutilating organ-preserving surgery with R0 margins and reduce the risk of intraoperative tumor rupture and bleeding or if achievement of microscopically negative margins is not feasible. Administering imatinib for approximately 3-12 mo,depending on the strictness of radiological follow-up and the burden of tumor, is advised to limit surgical morbidity. Functional imaging is advised to assess response to treatment, and unresponsive patients should undergo surgery without delay[1].Furthermore, mutational analysis can identify patients with imatinib-resistant forms,such as PDGFRA D842V, or those who require higher doses of imatinib in order to prevent delays in surgery.

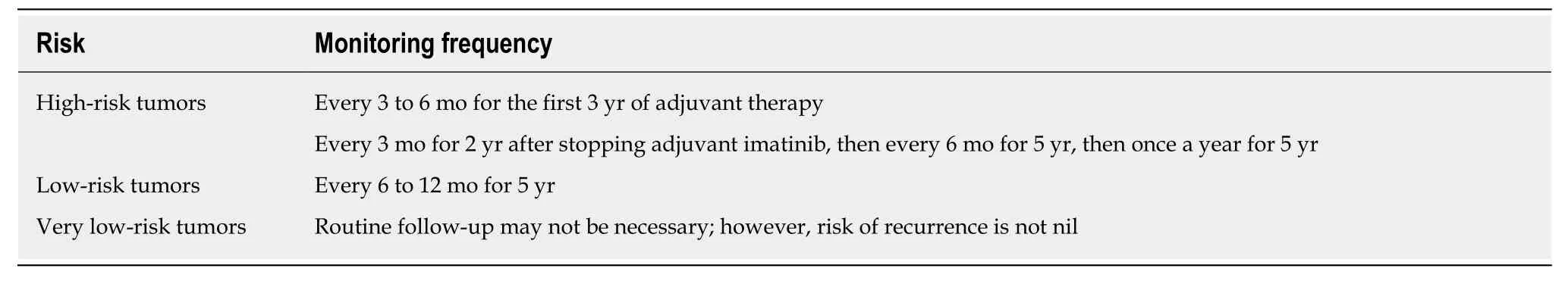

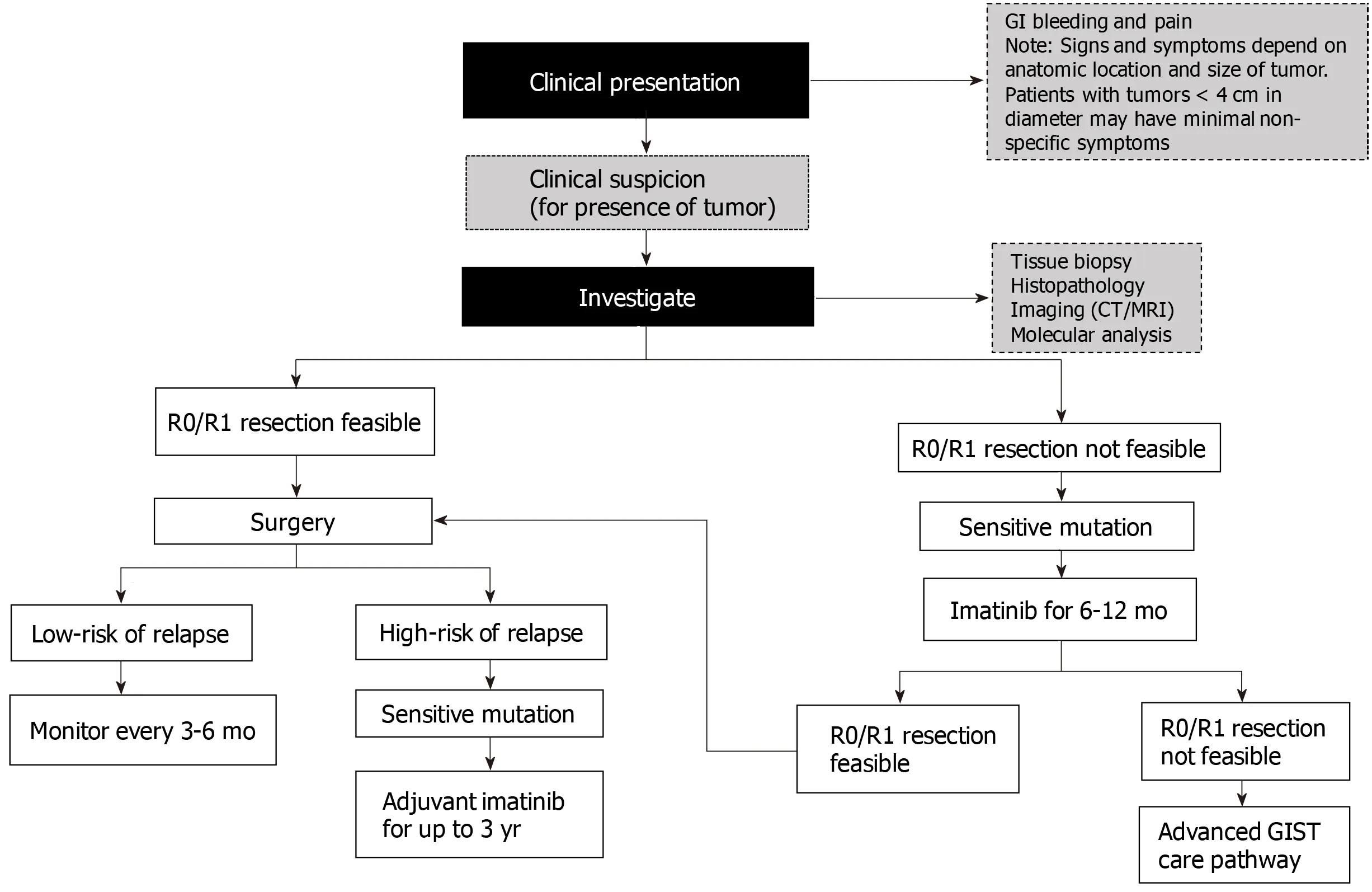

Postoperative follow-up:Postoperative follow-up is important for early detection and treatment of relapses[27]. Optimal follow-up timings remain undefined due to insufficient data on the frequency and intervals of routine postoperative follow-up visits[1,27]. Recurrences most commonly occur in the liver and/or the peritoneum;therefore, abdominal and pelvic contrast CT is adequate for detecting relapses. In young patients, MRI should be used to avoid the ionizing radiation risk associated with CT. The risk of relapse is particularly high during the first few years after surgery and following discontinuation of adjuvant imatinib therapy[27]. Therefore,based on a patient’s risk stratification (based on mitotic count, tumor size, and tumor site), CT or MRI can be used for monitoring, according to the schedules shown in Table 1[1]. Figure 2 shows an algorithm for managing localized primary GIST.

Figure 1 Five-year recurrence-free survival and overall survival. A: Five-year recurrence-free survival and overall survival at a median follow-up of 54 mo with 3-year vs 1-year imatinib adjuvant treatment in patients with resected gastrointestinal stromal tumors estimated to be at high risk of recurrence[39]. B: Five-year recurrence-free survival and overall survival at a median follow-up of 90 mo with 3-year vs 1-year imatinib adjuvant treatment in patients with resected gastrointestinal stromal tumors estimated to be at high risk of recurrence[40]. OS: Overall survival; RFS: Recurrence-free survival.

Management of non-localized GIST

Role of surgery:The role of complete surgical resection of localized GIST is well established; however, for patients with locally advanced, metastatic GIST, responding to imatinib therapy, the role of surgery is unclear[47]. A small Chinese trial of 41 GIST patients demonstrated higher 2-year PFS and OS rates in the surgery with imatinib group (88%; not reached)vsthe imatinib group (58%; 49 mo). Despite this uncertainty,surgery in patients with advanced GIST has the potential to be used as an adjunct to imatinib in responding patients with metastases or recurrent disease in an effort to improve disease-free survival and OS[48]. Ideally, surgery should be avoided in those with imatinib-resistant disease unless for emergency palliative intervention[48].

Although patients with advanced unresectable or metastatic GIST may achieve PR or stable disease while on imatinib, about half are highly likely to develop secondary resistance within 2 years[47]. Cytoreductive surgery may be considered in patients with metastatic GIST who respond to imatinib, especially if R0/R1 resection can be achieved. In patients with multifocal progression, surgery leads to poor outcomes[47].In patients with metastatic GIST treated with sunitinib, surgery may be feasible;however, resections are commonly incomplete, associated with complications and have unclear survival benefit[47]. Imatinib should be continued even if the surgical resection is complete.

First line:Imatinib, at the standard dose of 400 mg per day, has demonstrated efficacy in advanced, metastatic GIST with an average prolongation of median PFS time of 24 mo[49,50]. Higher doses have largely shown no clinical benefit. In two phase 3 trials,clinical benefit rates for imatinib 400 mg and 800 mg per day in patients withmetastatic GIST were approximately 90% and 88%, respectively[49,51]. However, this benefit can vary according to GIST mutation. Pooled analysis of 768 patients across four clinical trials revealed that patients with mutations inKITexon 11 and 9 and those with GIST WT, had objective response rates (complete or partial response) of 72%, 38%, and 28%, respectively[52,53]. A dose-dependent improvement in response was, however, seen in patients withKITexon 9 mutations[53]. GIST mutational status can also contribute to differences in overall OS and time to progression (TTP) events.Patients testing positive forKITexon 11 and 9 mutations and WT GIST genotypes had TTPs of 25, 17, and 12.8 mo, respectively. The corresponding OS improvement in these patients was 60, 38, and 49 mo, respectively[53]. Patients with GISTs harboring thePDGFRAD842V mutation appear to be resistant to imatinib[53]. Furthermore, GIST patients withSDHdeficiency orNF1mutation rarely respond to imatinib[54,55].Imatinib treatment interruption poses a threat to control of metastatic disease, as discontinuation has resulted in disease progression that may not be fully reversed by rechallenge[56,57].

Table 1 Monitoring frequency based on risk of recurrence[1]

Cytoreductive surgery, following a response to imatinib, has improved survival[58,59]. In fact, no evidence of disease was found after the procedure in 78% of patients who had achieved stable disease before surgery. The 12-mo OS and PFS rates in these patients were 95% and 80%, respectively.

These findings suggest testing patient genotype before starting treatment for metastatic GIST. In patients intolerant to or who progress on imatinib therapy,second-line therapy with sunitinib may be considered. Before progressing to secondline options, however, physicians should ensure patient compliance with imatinib therapy for at least 2 additional months with modification of the timing of tablet intake[60]. Furthermore, imatinib plasma levels can be checked; if low (< 1000 ng/mL)increasing the dose to 800 mg daily may be beneficial; if high, switching to second-line therapy is recommended[61]. Physicians should carefully consider potential drug interactions with imatinib: proton pump inhibitors are known to decrease imatinib plasma levels to subtherapeutic levels[53,62].

Second line:Sunitinib, an FDA-approved multitargeted TKI, is indicated in imatinibrefractory or imatinib-intolerant GIST patients[63,64]. This indication was approved following an international phase 3 trial of sunitinib vs. placebo in 312 GIST patients after imatinib failure. Patients receiving sunitinib had longer TTP (27 mo)vsplacebo(6 mo), despite low objective response rates (7%) and an absence of OS benefits over time. Sunitinib is recommended at a daily dose of 50 mg for 4 wk followed by a 2-wk rest interval; lower (37.5 mg), continuous daily dosing can also be used[63,65,66].

Response to sunitinib may also be driven by mutation type. Clinical benefit was observed to be higher in patients withKITexon 9 mutation and GIST WT (58% and 56%) than withKITexon 11 mutation (34%). After initial progression to imatinib, TTP was 19 mo in patients withKITexon 9 or PDGFRA mutationvs5 mo in patients withKITexon 11 mutation. In patients with secondaryKITexon 13 and 14 mutations, both OS and PFS were significantly longer than in those withKITexon 17 or 18 mutations.Common side effects relating to sunitinib include renal toxicity (proteinuria),hematological effects (myelosuppression, thrombotic microangiopathy), thyroid dysfunction (hypothyroidism), hypertension, and GI bleeding or perforation.

Third line:Regorafenib, at a daily dose of 160 mg taken for 21 d in 28-d cycles, has been approved for the treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic GIST after failure of or intolerance to imatinib and sunitinib therapy. A phase 2 trial of 34 GIST patients who experienced failure of imatinib and sunitinib demonstrated 26 patients with a clinical benefit with regorafenib (four had partial response), with a median PFS of 10 mo. In a confirmatory phase 3 trial of 129 GIST patients, PFS was higher for regorafenib (4.8) than placebo (0.9), without OS benefit[67]. In contrast to sunitinib,regorafenib may be beneficial for patients with metastatic and/or unresectable GIST harboringKITexon 11 mutations, and SDH-deficient GIST, but not GIST with secondaryKITexon 17 mutations[68]. The most common side effects associated with regorafenib include hypertension, hand-foot syndrome, and diarrhea.

Figure 2 Algorithm for the management of localized primary gastrointestinal stromal tumors. CT: Computed tomography; GI: Gastrointestinal; GIST:Gastrointestinal stromal tumors; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; R0: No residual tumor; R1: Microscopic residual tumor.

According to the NCCN guidelines, later lines of therapy after failure of the three FDA-approved drugs (imatinib, sunitinib, and regorafenib) include sorafenib and third generation TKIs such as pazopanib, nilotinib, ponatinib, or dasatinib. Sorafenib,at a dose of 400 mg twice daily, has also demonstrated efficacy in patients with metastatic GIST who have progressed on imatinib and sunitinib therapy[69]. In contrast, in the multicenter, phase 2 trial of sorafenib including 38 KIT-expressing GIST patients, the disease control rate was 68%, median PFS 5.2 mo, and median OS 11.6 mo[70].

Pazopanib achieved favorable 4-mo PFS rates in a phase 2 trial compared with placebo (45%vs18%, respectively;P= 0.03)[71]. Ponatinib has been shown to suppress allKITsecondary mutations with the exception of V654A[72]. The clinical benefit rate achieved with ponatinib therapy was 55% in heavily pretreated (including regorafenib) patients with GIST harboring primaryKITexon 11 mutation[73]. Dasatinib has proven to be active againstKITWT tumors, particularly PDGFRA D842V, which is normally resistant to imatinib[74]. Further details on these emerging therapies are provided in Table 2.

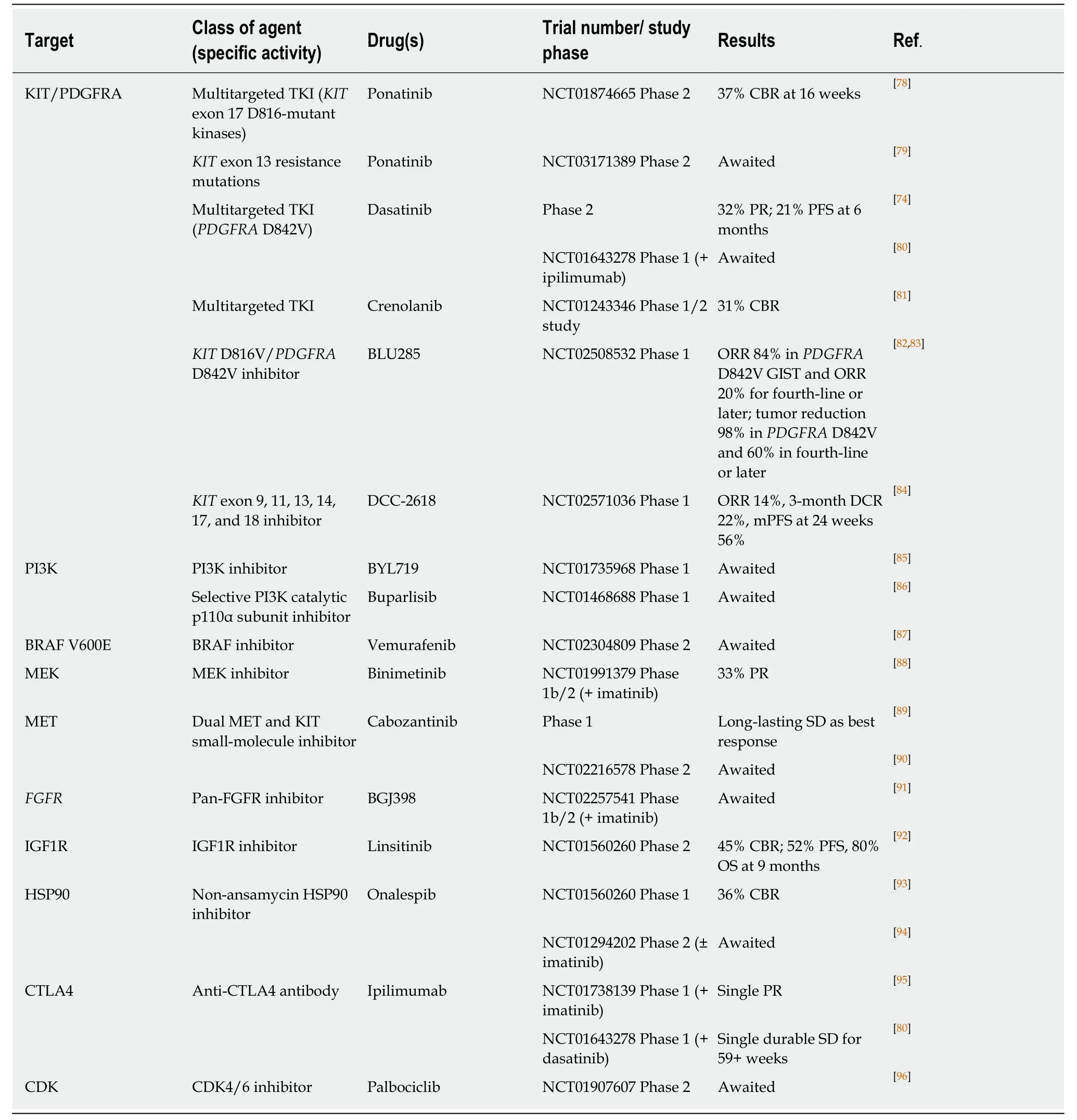

Emerging treatment options

Clinical trials for GIST are based on recent advances and understanding of molecular differences. Several new pathways have been targeted, alone or in combination, in clinical trials to overcome primary and/or secondary acquired resistance to existing GIST treatment. Table 2 outlines potential key therapeutic targets for GIST.

LOCAL CHALLENGES AND GAPS IN PATIENT MANAGEMENT

Diagnosis

Correct characterization of GIST at the time of initial diagnosis is crucial to the proper management of these tumors. Clinical decision making is based on histopathology,immunohistochemistry, and molecular diagnosis of the cancer subtype. Therefore, a multidisciplinary team at a comprehensive cancer care center is necessary for formulating patient care plans based on the best-available published evidence. Before a diagnostic and therapeutic strategy is initiated, suspected GIST patients require a discussion with a multidisciplinary tumor board, including sarcoma experts in medical oncology, surgical oncology, radiation oncology, radiology, and pathology.The development of local and national multidisciplinary meetings in the MiddleEastern region is mandatory but faces several obstacles, mainly the private medical system.

Table 2 Promising therapeutic agents in development for the treatment of advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor

Pretreatment biopsy of large tumors is mandatory in order to prevent unnecessary measures. Specialized endoscopists, diagnostic/intervention radiologists, and sarcoma surgeons are integral to the process of tumor sampling and staging. A tumor tissue sample helps ascertain subtype for a GIST diagnosis. Lack of experience and proper tools at a non-cancer facility contribute to poor tumor sampling and poor fixation and preservation of tumor structure. Therefore, training programs and awareness campaigns for medical doctors and surgeons on the proper management of GIST patients are essential to decrease the removal of uncharacterized tumors that might benefit from medical therapy only, such as lymphomas.

Another challenge is the lack of experts in pathological analysis of different types of sarcomas including GIST. First, without a wide immunostaining panel and molecular analyses, it is difficult to differentiate GIST from other pathologies. Proper pathological assessment with wide molecular profiling should be implemented through medical societies and regional groups. There is a lack of histopathologists with proper expertise in sarcoma in the Middle Eastern region, which highlights the need to implement targeted formations for specialists, with special focus on sarcomas and on different diagnostic methods (molecular analysis in GIST). Recent data have demonstrated the importance of next-generation DNA sequencing in identifying all possible mutations within a tumor sample and determining the correct treatment.However, next-generation sequencing is expensive, has a long runtime, and requires technical and interpretational expertise.

The final diagnostic challenge is the limited access to radiological assessments such as PET scans due to their high cost and limited availability, presenting a significant hurdle to proper diagnosis and subsequent management.

Current management

Surgery is critical to GIST management and remains the only potentially curative treatment for resectable GIST; however, oncologic surgery is still in its nascent stage and onco-surgeons are often inappropriately trained. The lack of harmony between the onco-/general surgeon and the medical oncologist is another challenge in defining the steps before and after diagnosis and staging. For those with locally advanced GISTs, preoperative imatinib mesylate for 6–9 mo to shrink the tumor, followed by complete cytoreductive surgery, is the optimal plan; early surgery by a general surgeon carries an increased risk of surgery-related morbidity and worse oncological outcomes. Most patients are managed by surgeons and gastroenterologists with limited expertise in oncology.

There is a lack of radiological availability in some regions (CT scans, MRIs, or PET scans), which may limit the initiation of neoadjuvant therapy or the optimal follow-up of GIST during therapy. In addition, health authorities across the Gulf region do not have access to any guidelines that regulate management of cancer patients at general hospitals or in the private sector. This has the potential to lead to poor management of patients outside a specialized cancer center by a non-specialized team.Comprehensive cancer care centers can guarantee the availability of specialized manpower and access to latest technology.

Access to treatment

Medication access and local formulary approvals are a big challenge and need to be optimized to enable optimal treatment of GIST patients. The medical systems in the region do not allow all patients full access to recently developed TKIs or even clinical trials. For example, the Arabian Gulf, which has a population of 20 million, has a healthcare system that is publicly funded. The treatment of GIST with TKIs represents a new era of molecular targeted therapy. Expensive drugs such as TKIs are reimbursed by the national health insurance system for its citizens; however, noncitizen residents have to find alternative methods to pay for treatment, which varies based on the Gulf country they reside in. For instance, in the United Arab Emirates,third-party insurance can cover treatment-related expenses within an annual budget;in Kuwait, surgery for cancer patients is allowed in the private sector but anti-cancer treatment is not allowed to be prescribed outside the Ministry of Health Cancer Center. Charities, such as the Patients Helping Fund Society in Kuwait takes the lead to reimburse treatment for non-citizen residents after a long process of financial assessment. Across the Gulf region, imatinib is reimbursed up to a dose of 400-800 mg orally per day for metastatic disease and for up to 3 years for adjuvant treatment of high-risk GISTs. Sunitinib can be prescribed and is reimbursed after imatinib failure,and regorafenib has recently become available for routine use, except in Iraq where it is not a formulary drug. In Lebanon, where the drug is reimbursed by all insurers including the Ministry of Public Health, the challenge is the sub-standard generics that might be included in the therapeutic arsenal. In some other countries, due to economic restrictions or war situations, such drugs might not be reimbursed.

The importance of setting guidelines in this region is to offer physicians an insight into proper management and drug usage with the available amenities. Another important drawback in the management of GIST patients is the limited access to international clinical trials in which patients might benefit from the latest treatment novelties without added costs.

Patient challenges

On the patient level, a better understanding of the risks associated with poor treatment compliance is needed. Early discontinuation of imatinib has severe consequences with an increase in relapse rates (up to 49% of early discontinuation rates in the PERSIST trial). Frequent physician visits and closer follow-up are recommended to ensure optimal compliance of TKI intake.

The Middle Eastern society is traditionally conservative with strong religious and cultural beliefs[75]. Cancer diagnosis is still considered, in some regions, as a death certificate and family bonds have an impact on limiting patients’ access to information about their health status[76]. Up to 40% of patients are unaware of their diagnosis,which could also impact their compliance with treatment[77]. In general, patients are apt to discontinue oral medications because of a lack of information concerning their initial diagnosis and prognosis. These limitations can be overcome by empowering the physician-patient relationship.

CONCLUSION

Overall, the lack of sufficient clinical trials, national disease registries, and regional scientific research into GIST epidemiology, tumor characteristics, prognostic features,tolerance to treatment, and quality of life of patients highlights the long road ahead in establishing standards of care that are consistent across treatment centers irrespective of geographical reach[6].

Counseling of patients and their family members concerning the value of preoperative treatment remains a challenge faced by some oncologists due to the risk of primary resistance to the treatment and the possibility of disease progression.

Multiple challenges remain for recurrent/metastatic disease management,including limited affordability of care, lack of proper testing of resistance to imatinib mesylate, and limited availability of subsequent lines of therapy after imatinib mesylate failure.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Medical writing support in the development of this manuscript was provided by Leris D’Costa of OPEN Health Dubai.

杂志排行

World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Novel zinc alloys for biodegradable surgical staples

- Peutz-Jeghers syndrome with mesenteric fibromatosis: A case report and review of literature

- Complex liver retransplantation to treat graft loss due to long-term biliary tract complication after liver transplantation: A case report

- Successful treatment of adult-onset still disease caused by pulmonary infection-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: A case report

- Isolated vaginal metastasis from stage I colon cancer: A case report

- Radiation recall dermatitis with dabrafenib and trametinib: A case report