Small bowel racemose hemangioma complicated with obstruction and chronic anemia: A case report and review of literature

2020-05-11JiXinFuYaNanZouZhiHaoHanHaoYuXinJianWang

Ji-Xin Fu, Ya-Nan Zou, Zhi-Hao Han, Hao Yu, Xin-Jian Wang

Abstract BACKGROUND Gastrointestinal hemangiomas are rare benign tumors. According to the size of the affected vessels, hemangiomas are histologically classified into cavernous,capillary, or mixed-type tumors, with the cavernous type being the most common and racemose hemangiomas being very rare in the clinic. Melena of uncertain origin and anemia are the main clinical manifestations, and other presentations are rare. Due to the rarity of gastrointestinal hemangiomas and lack of specific manifestations and diagnostic methods, preoperative diagnoses are often delayed or incorrect.CASE SUMMARY We report a 5-year-old girl who presented with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting for a duration of 10 h. The laboratory studies showed prominent anemia. Computed tomography and contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen revealed a small bowel obstruction caused by a giant abdominal mass. Segmental resection of the ileal lesions was performed through surgery,and the final pathology results revealed a diagnosis of racemose hemangioma complicated by a small bowel obstruction and simultaneous chronic anemia. CONCLUSION The current report will increase the understanding of the diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal hemangiomas and provide a review of the related literature.

Key words: Gastrointestinal hemangioma; Racemose hemangioma; Small bowel obstruction; Chronic anemia; Computed tomography; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Gastrointestinal hemangiomas are rare benign tumors, representing 0.05% of all gastrointestinal tumors[1]. These tumors usually present in young people with no sex predilection. Their main clinical manifestation is gastrointestinal bleeding of uncertain origin, which is defined as chronic or recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding of an unknown cause. Other forms of presentation include obstruction, intussusception,intramural hematoma, perforation, and platelet sequestration[2]. According to the size of the affected vessels, hemangiomas are histologically classified into cavernous,capillary, or mixed-type tumors, with the cavernous type being the most common and racemose hemangioma being very rare in the clinic[3]. In the gastrointestinal tract,these tumors are more frequently found in the jejunum. Computed tomography (CT)and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) are the main methods for diagnosing such lesions preoperatively, and capsule endoscopy is significantly helpful for diagnosing small bowel lesions[4]. Surgical resection is the ideal treatment.This study presents the unusual case of a 5-year-old girl who underwent segmental resection, and the final pathology results revealed a small bowel racemose hemangioma complicated by an obstruction and simultaneous chronic anemia. A review of the current literature was also provided to contextualize the findings of the present study.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 5-year-old female child was admitted to the Emergency Department of our hospital complaining of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting for a duration of 10 h.

History of present illness

The patient suddenly developed abdominal pain 10 h ago, which was total abdominal pain accompanied by nausea and vomiting. There was no pulsatile vomiting. The vomitus was the previously ingested food and yellow-green bile-like substance, and she vomited three times. There was no hematemesis, no fever, no chest tightness or suffocation, and no diarrhea. The abdominal symptoms gradually became aggravated.

History of past illness and personal and family history

The patient was born after a full-term pregnancy by spontaneous vaginal delivery and had a history of iron deficiency anemia for 1 year. Prior to this admission, the patient had been treated with supplemental iron as recommended by her pediatrician for her symptoms but had shown no improvement. Her parents were healthy, and there were no close relatives. Her mother had a healthy pregnancy.

Physical examination

On the physical examination, her heart rate was 99 beats per minute, and her blood pressure was 12/8 KPa. There were no lesions in the oropharynx, and her neck was supple. The lungs were clear, and her heart rate was regular, without a murmur. Her abdomen was soft, and an abdominal mass could be felt on the left lower abdomen,which was tender. The neurologic examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory examinations

The white cell count was 5.41 × 109/L, with 77.8% of neutrophils; hemoglobin was 78 g/L, with a hematocrit level of 27.7%, and the platelet count was 356 × 109/L. The serum ferritin level was less than 1.0 μg/L (normal range: 15-200). The electrocardiogram and chest X-ray were normal.

Imaging examinations

An initial imaging evaluation by ultrasound revealed an enormous tumor mass in the middle of the abdomen and pelvis with an inhomogeneous echo pattern that was 10.3 cm × 4.0 cm in size, and several strong echoes and grid-like structures could be seen in the mass with a low blood flow signal on color Doppler flow imaging.

The abdominal lesions were further evaluated by an abdominal CT scan and CECT.The former revealed an ill-circumscribed mass of mixed density in the left lower abdomen that extended to the pelvis. There were multiple high-density nodes in the mass (Figure 1A). The latter revealed that the mass exhibited heterogeneous enhancement following contrast administration. In the venous phase, there were thick and tortuous blood vessels in the mass, which were connected to each other by a honeycomb or racemose appearance (Figure 1B-1D).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Considering the large abdominal mass in a young woman with multiple calcifications,the most likely preoperative diagnosis was a teratoma complicated by a small bowel obstruction. However, the final diagnosis by histopathology was small bowel racemose hemangioma complicated by an obstruction and anemia (Figure 2).

TREATMENT

Laparoscopy was performed, and the result revealed a 10 cm × 4 cm lesion on the ileum; a vascular nature was suspected due to the bluish purple coloration,compressibility, and presence of varices on the surface (Figure 3). The mass invaded the intestinal canal and required a dilated proximal intestinal and segmental small bowel resection.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient was discharged without immediate complications on the 8th day, and the hemoglobin increased to 123 g/L at the second month after the operation.

DISCUSSION

Hemangiomas are defined as congenital benign vascular lesions that are venous malformations, not true tumors. Hemangiomas are classified into cavernous,capillary, or mixed tumors; the cavernous type is the most common, and racemose hemangioma is very rare[3]. According to the biological characteristics of hemangioma,Fishmanet al[5]divided them into two categories: Hemangioma and vascular malformations. According to the angiographic findings, vascular malformations can be divided into high-flow and low-flow types, and racemose hemangioma is a complex high-flow type of arteriovenous malformation, which accounts for approximately 1.5% of all hemangiomas and mostly occurs in the head, neck, and limbs[6,7]. Hemangiomas of the gastrointestinal tract are rare, accounting for only 0.05% of all intestinal neoplasms and 7%-10% of all benign tumors of the small bowel[8]. According to the literature, small bowel racemose hemangiomas with obstructions and chronic anemia were rarely reported, which makes our case even more unusual.

The PubMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed), WanFang Data(http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/index.html), and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI; http://kns.cnki.net/kns/brief/default_result.aspx) databases were investigated between 2009 and 2019 to analyze the clinicopathological features and outcomes of patients with gastrointestinal hemangiomas by searching for MeSH terms and keywords such as “hemangioma”, “capsule endoscopy”, “double balloon enteroscopy”, “anemia”, and “gastrointestinal bleeding”. The reference lists were screened to identify additional relevant studies, and a standardized form was used for data extraction. Finally, there were approximately 25 cases of gastrointestinal hemangiomas[9-31]. The patient information is summarized in Table 1 to analyze the clinicopathological features (Table 2). The mean age of the patients with gastrointestinal hemangioma was 42.9 years (range: 0-75 years). The sex distribution included 14 males and 11 females (Male:Female = 1.27:1), which is consistent with the results of Durer Cet al[14]. Gastrointestinal hemangiomas were mainly located in the jejunum and ileum, accounting for 36% and 24% of all gastrointestinal hemangiomas,respectively. The sizes of the gastrointestinal hemangiomas ranged widely from 0.3 cm to 32.5 cm, and the average size was approximately 7.44 cm. In our case, the patient was a 5-year-old girl, and the lesion was confirmed to be located in the ileum with a size of 9 cm x 6 cm.

Figure 1 Pre-operative abdominal computed tomography and contrast-enhanced computed tomography images. A: Abdominal computed tomography image showing an ill-circumscribed mass of mixed density in the left lower abdomen (long white arrow) with proximal small bowel dilatation (orange arrow) and multiple nodes with high density in the mass (short white arrow); B-D: Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography images revealing that the mass exhibited heterogeneous enhancement following contrast administration and there were thick and roundabout blood vessels in the mass (orange arrow). There were multiple dilated intestines and air-fluid level within the intestine (white arrow).

Clinically, gastrointestinal hemangiomas are symptomatic in 90% of cases, unlike other benign tumors of the gastrointestinal tract that tend to present as an incidental finding[32]. The most frequent sign is chronic gastrointestinal bleeding, which causes anemia of an unknown origin and rarely leads to massive bleeding. Occasionally,these tumors may cause intestinal obstructions, intussusception, intramural hematoma, perforation, and platelet sequestration[2]. Among the 25 patients analyzed in our literature, melena, which was observed in 11 (44%) patients, was the main clinical symptom, followed by anemia in 7 (28%), and dizziness in 5 (20%). However,shock and intestinal obstructions caused by gastrointestinal hemangioma were only observed in 1 (4%) patient. Based on the histological examinations, there have been 15 reported cases of cavernous hemangioma, 3 cases of capillary hemangioma[16,26,28], 2 cases of racemose hemangioma[29,31], 1 case of hemolymphangioma[18], and 1 case of hemangiolymphangioma[19]. Overall, acute intestinal obstruction and chronic anemia caused by a small intestinal racemose hemangioma as in our case are extremely rare.

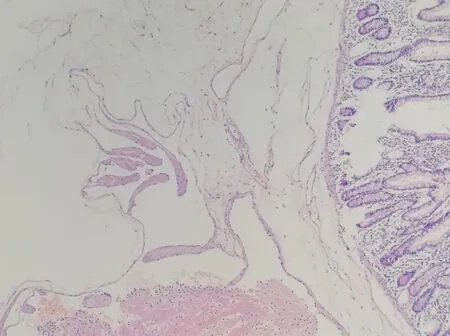

Figure 2 Postoperative histopathological image reveals a small bowel racemose hemangioma (HE, × 100).

Gastrointestinal hemangioma is difficult to diagnose preoperatively, especially for small intestinal hemangiomas. Since the most frequent clinical presentation in these patients is gastrointestinal bleeding, the patients frequently undergo gastroscopy and colonoscopy studies with normal results, as in the reported case. However, when the lesions are located in the stomach or colorectal region, gastroscopy and colonoscopy can still have great value in the diagnosis and treatment of this disease. In the literature, among the 25 patients, 10 hemangiomas were located in the stomach or colorectum, 9 of which were diagnosed by endoscopy before the operation. A simple abdominal X-ray may be useful if phleboliths (50% of cases), obstructions, or perforations are present[1,33]. In our literature review, phleboliths were recognized overlying the right sacrum by a preoperative abdominal X-ray in one case[11]. CT and CECT are fundamental tools in the preoperative diagnosis of gastrointestinal hemangiomas, especially in emergency situations, because of their speed, availability,and ability to diagnose extraintestinal lesions. Due to the large degree of vascularity,gastrointestinal hemangiomas are homogenously and significantly enhanced on CECT. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), unlike CT, can demonstrate blood flow in the lesion without the administration of contrast medium, and phleboliths are usually void of signal on T1- and T2-weighted images[1]. For colorectal hemangioma,preoperative MRI can define the size of the lesion, which has great significance for treatment. In our retrospective analysis of 25 patients, half of all positive results before surgery were acquired by CT and/or CECT, and 16% were from MRI. Small bowel video capsule endoscopy (VCE) is a noninvasive imaging test and can be recommended when the source of the bleeding remains unidentified after upper and lower endoscopy. On the other hand, double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) is an invasive and highly sensitive diagnostic tool that provides both therapeutic and diagnostic interventions[2]. There were 15 cases of small intestinal hemangioma in our literature, 9 of which were preoperatively diagnosed by small bowel VCE and 6 by DBE. Undoubtedly, small bowel VCE and DBE are very important for the diagnosis of small intestinal hemangiomas. However, small bowel VCE and DBE are not suitable for critical patients with gastrointestinal hemangiomas, such as those with massive hemorrhage, intestinal obstructions, or intussusception. In addition, 30% of the results were false positives, and 20% of the examinations were incomplete[11].

Based on the literature we reviewed and the CT images of our patient, we summarized the following features of gastrointestinal hemangiomas: (1) CT scan:Tumors tend to appear with mixed density, and there is a blurred boundary between the tumor and the surrounding intestinal tissue; additionally, multiple calcifications representing phleboliths can be recognized inside the tumor on approximately half of all CT studies; (2) CECT: The masses exhibit heterogeneous enhancement following contrast administration; in the venous phase, thick and tortuous blood vessels are present inside the tumor on CT images, and phleboliths can be found in some cases;and (3) For racemose hemangiomas, the characteristic CT manifestations include a dilated feeding artery, malformed vessels, and thick and tortuous draining veins[11,32,34].Phleboliths are secondary to thrombosis of the intralesional vessels and subsequent partial or total calcifications of the thrombus and are an important diagnostic criterion that can be observed in 26%-50% of adult patients, especially in young patients, and phleboliths are virtually pathognomonic of hemangiomas if they are grouped[33-35].Phleboliths and malformed vessels were evident in our case.

The main treatment for hemangiomas is surgical resection of the affected segment[1,10,36]. Since hemangiomas never metastasize to the lymph nodes or distant organs, local resection is sufficient. However, in some cases of polypoid lesions accessible by endoscopy, especially those located in the stomach or colorectal region,it may be possible to perform polypectomy and cauterization. However, these are still controversial options because of the risk for uncontrollable bleeding and intestinal perforation. In the literature, surgical resection was still the main treatment for gastrointestinal hemangiomas and was applied in 80% of all cases. However, there was an endoscopic resection performed for a stomach hemangioma with a size of 4 cm × 2 cm, resulting in a good clinical course[18]. In terms of drug therapy, Kayaet al[12]reported a case of neonatal gastric hemangioma successfully cured by propranolol.However, in symptomatic hemangiomas, which may be associated with potentially life-threatening massive bleeding, perforations, intestinal obstructions, and intussusception, surgical resection is the preferred treatment option. Gastrointestinal hemangiomas usually have a satisfying prognosis, and there is no evidence in the literature on the recurrence of hemangiomas[10,13]. Our patient underwent partial small bowel resection, and two months after the operation, her hemoglobin increased to 123 g/L, with a hematocrit level of 40.6%.

Figure 3 Intraoperative image showing that there was a 10 cm × 4 cm lesion on the ileum with bluish purple coloration and compressible varices on its surface.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, hemangiomas of the small intestine are a rare but significant source of gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Since the main symptoms of hemangiomas are not specific, the clinical diagnosis is often delayed or incorrect, and the preoperative diagnosis was mistaken for a teratoma in our case. However, rare pathologies do occur and most importantly, they can present in an unspecific presentation. Therefore,we can say that although gastrointestinal hemangiomas are rare tumors, they should be considered in the differential diagnoses of patients, especially children, who present with gastrointestinal bleeding of an obscure origin or other abdominal symptoms.

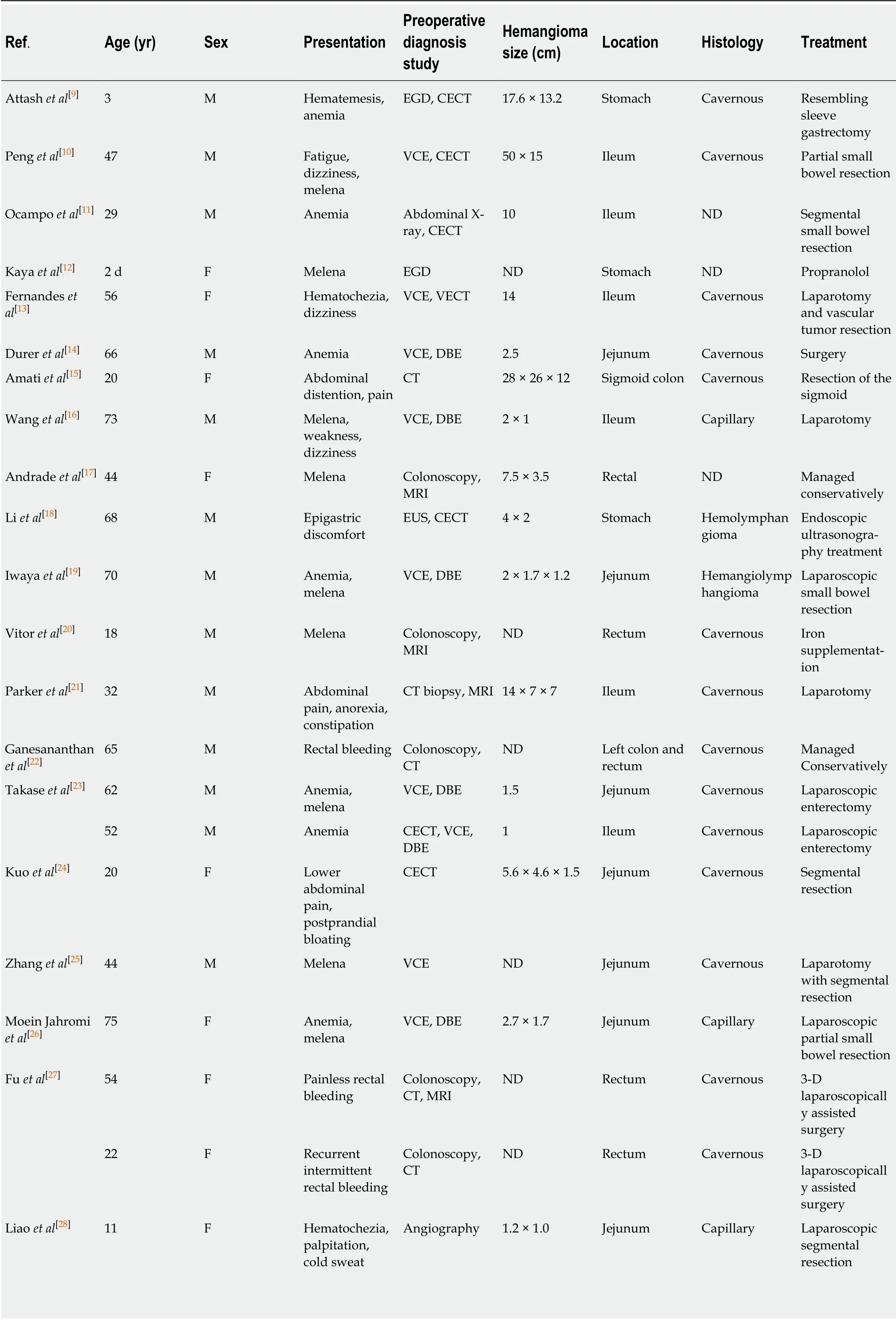

Table 1 Gastrointestinal hemangiomas reported in the literature between 2009 and 2019

ND: Not described; VCE: Video capsule endoscopy; DBE: Double-balloon enteroscopy; CT: Computed tomography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging;EUS: Endoscopic ultrasonography; CECT: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography; EGD: Esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

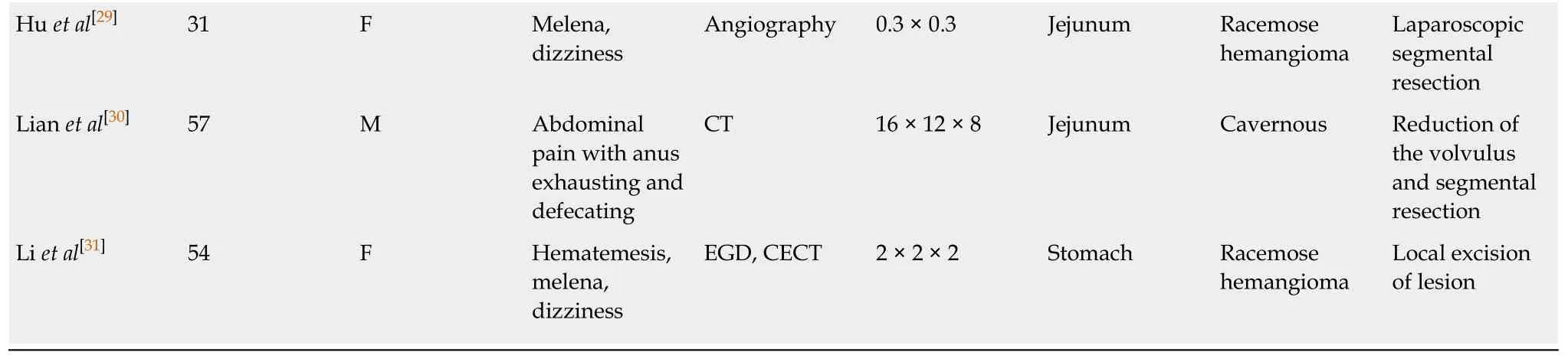

Table 2 Clinicopathological features of gastrointestinal hemangiomas

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- SARS-COV-2 infection (coronavirus disease 2019) for the gastrointestinal consultant

- Optimized timing of using infliximab in perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease

- Intestinal epithelial barrier and neuromuscular compartment in health and disease

- Gastrointestinal cancer stem cells as targets for innovative immunotherapy

- Is the measurement of drain amylase content useful for predicting pancreas-related complications after gastrectomy with systematic lymphadenectomy?

- Silymarin, boswellic acid and curcumin enriched dietetic formulation reduces the growth of inherited intestinal polyps in an animal model