Lifestyle factors and long-term survival of gastric cancer patients:A large bidirectional cohort study from China Zhao LL,

2020-05-11LuLuZhaoHuangHuangYangWangTongBoWangHongZhouFuHaiMaHuRenPengHuiNiuDongBingZhaoYingTaiChen

Lu-Lu Zhao, Huang Huang, Yang Wang, Tong-Bo Wang, Hong Zhou, Fu-Hai Ma, Hu Ren, Peng-Hui Niu,Dong-Bing Zhao, Ying-Tai Chen

Abstract BACKGROUND Lifestyle factors such as body mass index (BMI), alcohol drinking, and cigarette smoking, are likely to impact the prognosis of gastric cancer, but the evidence has been inconsistent. AIM To investigate the association of lifestyle factors and long-term prognosis of gastric cancer patients in the China National Cancer Center. METHODS Patients with gastric cancer were identified from the China National Cancer Center Gastric Cancer Database 1998-2018. Survival analysis was performed via Kaplan-Meier estimates and Cox proportional hazards models. RESULTS In this study, we reviewed 18441 cases of gastric cancer. Individuals who were overweight or obese were associated with a positive smoking and drinking history (P = 0.002 and P < 0.001, respectively). Current smokers were more likely to be current alcohol drinkers (61.3% vs 10.1% vs 43.2% for current, never, and former smokers, respectively, P < 0.001). Multivariable results indicated that BMI at diagnosis had no significant effect on prognosis. In gastrectomy patients,factors independently associated with poor survival included older age (HR =1.20, 95%CI: 1.05-1.38, P = 0.001), any weight loss (P < 0.001), smoking history of more than 30 years (HR = 1.14, 95%CI: 1.04-1.24, P = 0.004), and increasing pTNM stage (P < 0.001). CONCLUSION In conclusion, our results contribute to a better understanding of lifestyle factors on the overall burden of gastric cancer and long-term prognosis. In these patients,weight loss (both in the 0 to 10% and > 10% groups) but not BMI at diagnosis was related to survival outcomes. With regard to other factors, smoking history of more than 30 years conferred a worse prognosis only in patients who underwent gastrectomy. Extensive efforts are needed to elucidate mechanisms targeting the complex effects of lifestyle factors.

Key words: Gastric cancer; Lifestyle factors; Prognosis; Cohort study; Body mass index;Cigarette smoking

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality and the sixth most common cancer globally[1]. More than 70% of new cases occur in developing countries,and half of the world’s total cases occur in Eastern Asia, mainly in China[2]. As the patient population grows, factors contributing to improved or adverse survival are becoming a focus of increasing interest.

Obesity defined as high body mass index (BMI) results from the expansion of white adipose tissue, commonly referred to as fat. To date, evidence for the association between BMI and prognosis in gastric cancer patients has been inconsistent. Some studies[3-8]have reported that being overweight was associated with improved longterm survival for gastric cancer patients who underwent gastrectomy, whereas other results[9-16]showed that BMI was not a prognostic factor. Three studies[17-19]even demonstrated poor survival of gastric cancer patients with higher BMI. However,some previous studies have used coarse categories, such as BMI < 25.0 and ≥ 25[8,15,20,21].Furthermore, these results may not apply to the Chinese population due to the different BMI categorization criteria for Asians; therefore, the association between BMI and prognosis is unclear in China.

Similarly, the prognostic effects of alcohol drinking and smoking status at diagnosis of gastric cancer are also contradictory, although cigarette smoking is known to be associated with stomach cancer risk[22,23]. Alcohol drinking at diagnosis was reported to decrease survival in patients with gastric cancer in some studies[24,25], while several other studies[26,27]did not confirm this finding. Some studies[28-31]have shown a positive association between smoking and overall survival (OS) in gastric cancer, while other studies[24,26,32]have found that smoking status was not statistically related to prognosis.There is a deficiency in most published studies, especially prospective studies, which have not adjusted for potentially significant covariates such as gastrectomy.

Thus, we conducted a single-center, large-scale bidirectional cohort study in the China National Cancer Center to investigate the three major lifestyle factors mentioned above - BMI, alcohol drinking, and smoking - and attempted to clarify the association of these factors with the OS of patients with gastric cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Population

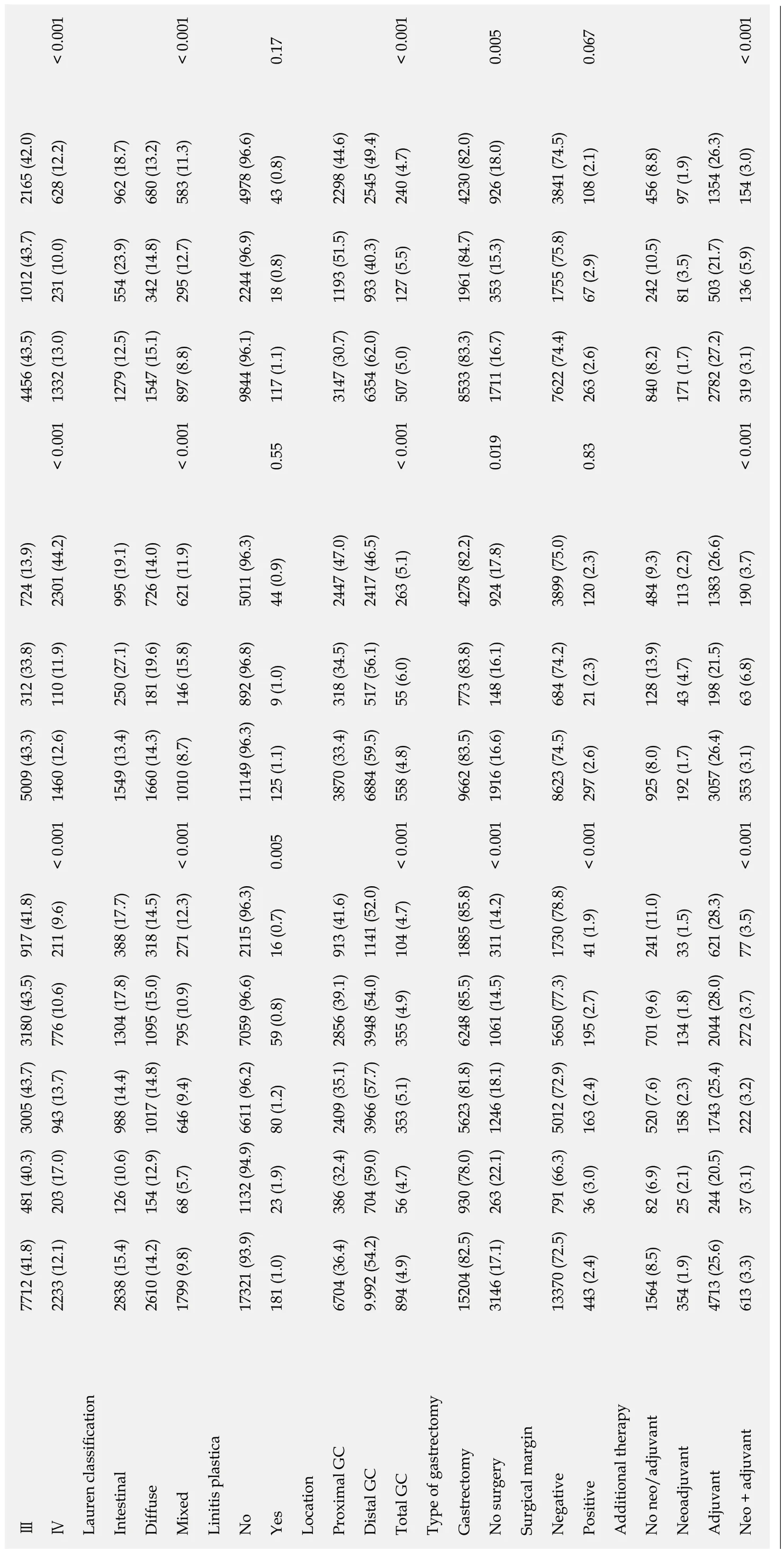

All patient records were abstracted from the China National Cancer Center Gastric Cancer Database. The China National Cancer Center Gastric Cancer Database is a clinical gastric cancer database based on a huge bidirectional cohort, which was sourced from the China National Cancer Center, a single but large-volume institution with patients from all over China from 1998 to 2018. After the diagnosis of gastric cancer was confirmed by pathology, 18441 patients were included in this study. The AJCC 8thedition was used for TNM staging. The median follow-up of gastric cancer patients was 62.7 ± 3.5 mo until December 2018. 1818 patients were lost during the follow-up period with a loss rate of 9.86%. The geographical locations of these gastric cancer patients are shown in Figure 1.

After the analyses of all included gastric cancer patients irrespective of surgery, we further analyzed three detailed subgroups: Consisting of gastrectomy patients, no surgery patients, and only gastric cancer patients with curative gastrectomy.Gastrectomy was defined as surgery with or without D2 lymphadenectomy, while curative gastrectomy was defined as patients who underwent surgery with D2 lymphadenectomy and had negative margins.

Statistical analysis

BMI at diagnosis was calculated as weight at diagnosis (kg) of gastric cancer divided by the square of height (m2). For the analysis of BMI according to the Asian criteria,patients were stratified according to the following BMI categories: Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), healthy weight (≥ 18.5 to < 23 kg/m2), overweight (≥ 23 to < 27.5.0 kg/m2) and obese (≥ 27.5 kg/m2).

Other lifestyle variables related to cigarette smoking included smoking status(never, current, and former smokers), time since quitting smoking (1-9 and ≥ 10 years), number of cigarettes per day (≤ 20, 21-39, and ≥ 40), and duration of smoking(1-29 and ≥ 30 years). For alcohol drinking, drinking status (never, current, and former drinkers) and amount of alcohol consumed per day (light drinkers, < 15.0 g; moderate drinkers, ≥ 15.0 g to < 53.5 g; and heavy drinkers, ≥ 53.5 g) was included. Subjects who quit smoking or drinking within one year before the present admission were regarded as current smokers or drinkers, respectively.

Categorical variables were compared using theχ2test, and continuous variables were analyzed by the Student’st-test. Survival curves were plotted for total patients,no-surgery, gastrectomy and only curative gastrectomy groups, respectively, using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Hazard ratios (HRs)and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to estimate the risk of death by employing the multivariate Cox proportional hazards models with adjustment for gender, age, pTNM stage, adjuvant therapies, and gastrectomy. The group with healthy weight (≥ 18.5 to < 23 kg/m2) was the reference group. A two-sidedPvalue less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All the statistical analyses were performed using SAS software v9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics

In this study, we included 18441 gastric cancer patients diagnosed between 1998 and 2018 (Table 1). Of these subjects, more than half were males (13533, 73.4%) with a median age of 58.5 years. Of the total subjects, 84.5% experienced weight loss at diagnosis when compared with their usual weight, 40.5% had a smoking history, and 33.2% had a drinking history. During the follow-up period, 4717 (25.6%) deaths were recorded in our database.

Compared to those with a healthy BMI at diagnosis, overweight and obese patients had more weight loss (0% to 10%) than patients with healthy weight (81.6%vs81.9%vs75.9%,P< 0.001). Underweight patients were more likely to be diagnosed at a later stage than other groups (pTNM IV, 17.0%vs13.7%vs10.6%vs9.6%,P< 0.001).

Current drinkers tended to be at a later pTNM stage (stage IV, 44.2%vs12.6%vs11.9%,P< 0.001) with a proximal location in the stomach (47.0%vs33.4%vs34.5%)than never or former drinkers. In terms of cigarette smoking, former smokers were older (aged ≥ 66 years, 37.9%vs30.0vs23.0%,P< 0.001) than never or current smokers. Current smokers were also more likely to be current alcohol drinkers (61.3%vs 10.1% vs 43.2%, P < 0.001) as compared to never or former smokers.

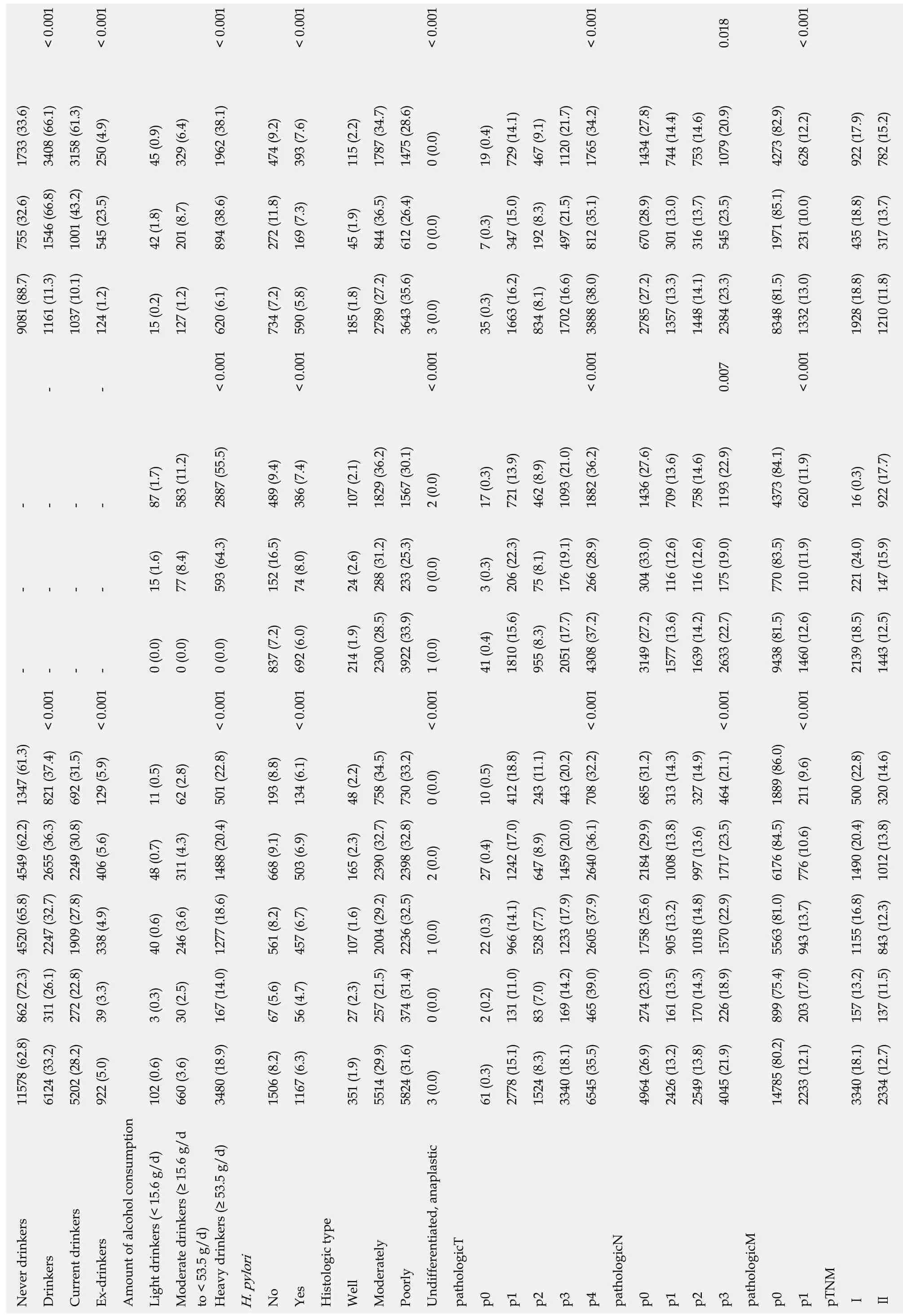

Table 1 Comparison of 18441 gastric cancer patients' characteristics

< 0.001< 0.001< 0.001< 0.001< 0.001< 0.001 0.018< 0.001 1733 (33.6)3408 (66.1)3158 (61.3)250 (4.9)45 (0.9)329 (6.4)1962 (38.1)474 (9.2)393 (7.6)115 (2.2)1787 (34.7)1475 (28.6)0 (0.0)19 (0.4)729 (14.1)467 (9.1)1120 (21.7)1765 (34.2)1434 (27.8)744 (14.4)753 (14.6)1079 (20.9)4273 (82.9)628 (12.2)922 (17.9)782 (15.2)755 (32.6)1546 (66.8)1001 (43.2)545 (23.5)42 (1.8)201 (8.7)894 (38.6)272 (11.8)169 (7.3)45 (1.9)844 (36.5)612 (26.4)0 (0.0)7 (0.3)347 (15.0)192 (8.3)497 (21.5)812 (35.1)670 (28.9)301 (13.0)316 (13.7)545 (23.5)1971 (85.1)231 (10.0)435 (18.8)317 (13.7)9081 (88.7)1161 (11.3)1037 (10.1)124 (1.2)15 (0.2)127 (1.2)734 (7.2)185 (1.8)2789 (27.2)3643 (35.6)35 (0.3)1663 (16.2)834 (8.1)1702 (16.6)2785 (27.2)1357 (13.3)1448 (14.1)2384 (23.3)8348 (81.5)1928 (18.8)1210 (11.8)--< 0.001 620 (6.1)< 0.001 590 (5.8)< 0.001 3 (0.0)< 0.001 3888 (38.0)0.007< 0.001 1332 (13.0)----87 (1.7)583 (11.2)2887 (55.5)489 (9.4)386 (7.4)107 (2.1)1829 (36.2)1567 (30.1)2 (0.0)17 (0.3)721 (13.9)462 (8.9)1093 (21.0)1882 (36.2)1436 (27.6)709 (13.6)758 (14.6)1193 (22.9)4373 (84.1)620 (11.9)16 (0.3)922 (17.7)----15 (1.6)77 (8.4)593 (64.3)152 (16.5)74 (8.0)24 (2.6)288 (31.2)233 (25.3)0 (0.0)3 (0.3)206 (22.3)75 (8.1)176 (19.1)266 (28.9)304 (33.0)116 (12.6)116 (12.6)175 (19.0)770 (83.5)110 (11.9)221 (24.0)147 (15.9)-< 0.001 --< 0.001 -0 (0.0)0 (0.0)< 0.001 0 (0.0)837 (7.2)< 0.001 692 (6.0)214 (1.9)2300 (28.5)3922 (33.9)< 0.001 1 (0.0)41 (0.4)1810 (15.6)955 (8.3)2051 (17.7)< 0.001 4308 (37.2)3149 (27.2)1577 (13.6)1639 (14.2)< 0.001 2633 (22.7)9438 (81.5)< 0.001 1460 (12.6)2139 (18.5)1443 (12.5)11578 (62.8) 862 (72.3) 4520 (65.8) 4549 (62.2) 1347 (61.3)311 (26.1) 2247 (32.7) 2655 (36.3) 821 (37.4)272 (22.8) 1909 (27.8) 2249 (30.8) 692 (31.5)129 (5.9)11 (0.5)62 (2.8)193 (8.8)134 (6.1)48 (2.2)0 (0.0)10 (0.5)243 (11.1)327 (14.9)211 (9.6)406 (5.6)48 (0.7)311 (4.3)668 (9.1)503 (6.9)165 (2.3)2 (0.0)27 (0.4)1242 (17.0) 412 (18.8)647 (8.9)1008 (13.8) 313 (14.3)776 (10.6)1012 (13.8) 320 (14.6)338 (4.9)40 (0.6)246 (3.6)561 (8.2)457 (6.7)107 (1.6)1 (0.0)22 (0.3)528 (7.7)39 (3.3)3 (0.3)30 (2.5)167 (14.0) 1277 (18.6) 1488 (20.4) 501 (22.8)67 (5.6)56 (4.7)27 (2.3)257 (21.5) 2004 (29.2) 2390 (32.7) 758 (34.5)374 (31.4) 2236 (32.5) 2398 (32.8) 730 (33.2)0 (0.0)2 (0.2)131 (11.0) 966 (14.1) 83 (7.0)169 (14.2) 1233 (17.9) 1459 (20.0) 443 (20.2)465 (39.0) 2605 (37.9) 2640 (36.1) 708 (32.2)274 (23.0) 1758 (25.6) 2184 (29.9) 685 (31.2)161 (13.5) 905 (13.2) 170 (14.3) 1018 (14.8) 997 (13.6)226 (18.9) 1570 (22.9) 1717 (23.5) 464 (21.1)203 (17.0) 943 (13.7) 157 (13.2) 1155 (16.8) 1490 (20.4) 500 (22.8)137 (11.5) 843 (12.3) 6124 (33.2)5202 (28.2)922 (5.0)102 (0.6)660 (3.6)3480 (18.9)1506 (8.2)1167 (6.3)351 (1.9)5514 (29.9)5824 (31.6)3 (0.0)61 (0.3)2778 (15.1)1524 (8.3)3340 (18.1)6545 (35.5)4964 (26.9)2426 (13.2)2549 (13.8)4045 (21.9)14785 (80.2) 899 (75.4) 5563 (81.0) 6176 (84.5) 1889 (86.0)2233 (12.1)3340 (18.1)2334 (12.7)Never drinkers Drinkers Current drinkers Ex-drinkers Amount of alcohol consumption Light drinkers (< 15.6 g/d)Moderate drinkers (≥ 15.6 g/d to < 53.5 g/d)Heavy drinkers (≥ 53.5 g/d)H. pylori No Yes Histologic type Well Moderately Poorly Undifferentiated, anaplastic pathologicT p0 p1 p2 p3 p4 pathologicN p0 p1 p2 p3 pathologicM p0 p1 pTNMⅠⅡ

H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; GC: Gastric cancer.

Figure 1 The geographical locations of gastric cancer patients in the China National Cancer Center Gastric Cancer Database, 1998–2018.

Survival outcomes in univariate analysis

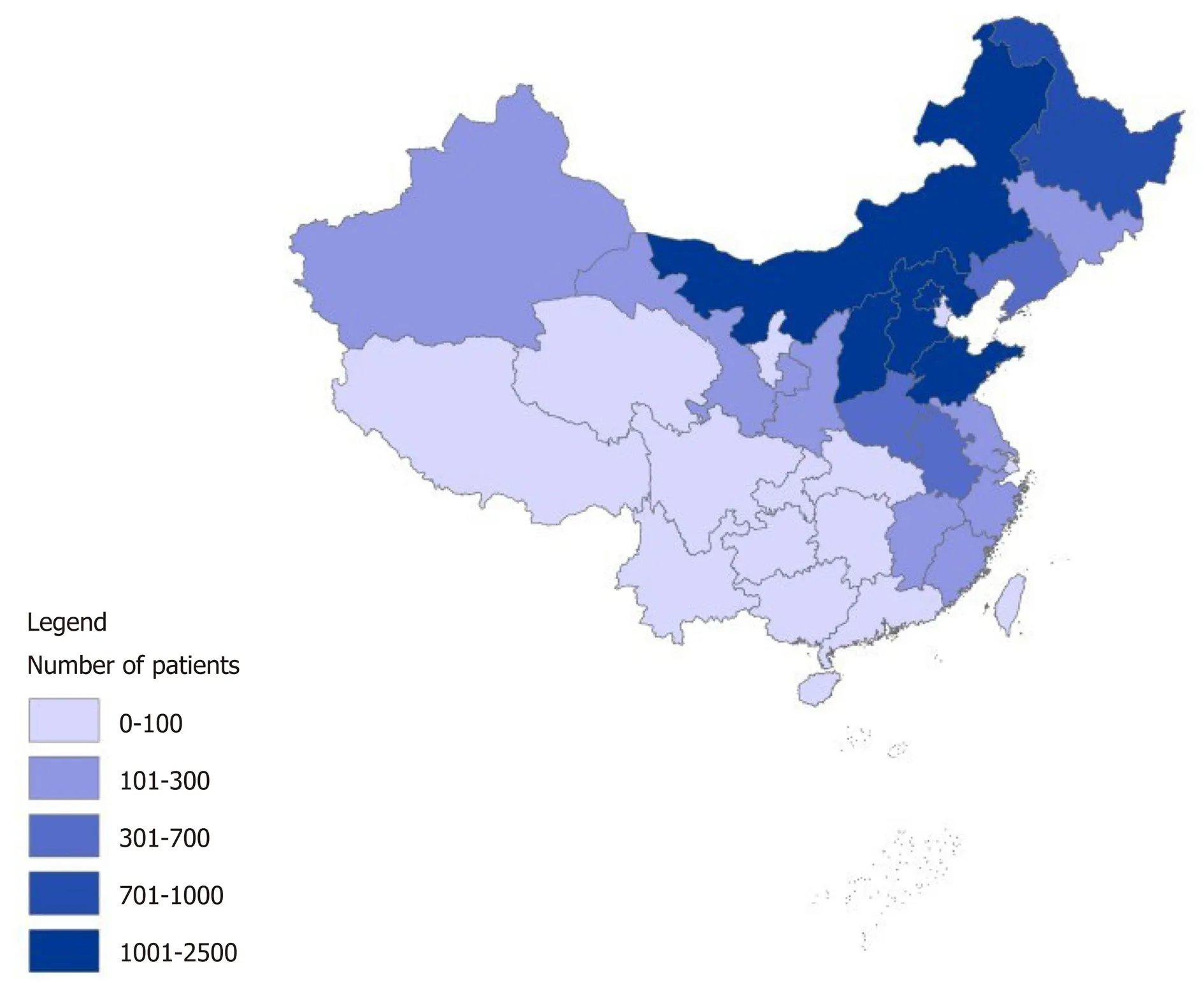

Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier curves for OS of different BMIs at diagnosis in total gastric cancer patients, no surgery, gastrectomy, and only curative gastrectomy patients. The median OS of total patients for each BMI category was as follows:underweight, 12.5 years; healthy weight, 13.0 years; overweight, 13.6 years; and obese,13.6 years (P< 0.001). For no surgery patients, the results were as follows:Underweight, 5.7 years; healthy weight, 5.0 years; overweight, 5.9 years; and obese,6.1 years (P= 0.26). For the gastrectomy group, survival status was as follows:Underweight, 14.0 years; healthy weight, 14.0 years; overweight, 14.2 years; and obese, 14.4 years (P< 0.001). For the only curative gastrectomy group, survival status was as follows: Underweight, 14.1 years; healthy weight, 14.3 years; overweight, 14.3 years; and obese, 14.5 years (P= 0.002). The 3- and 5-year OS for different gastrectomy groups are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

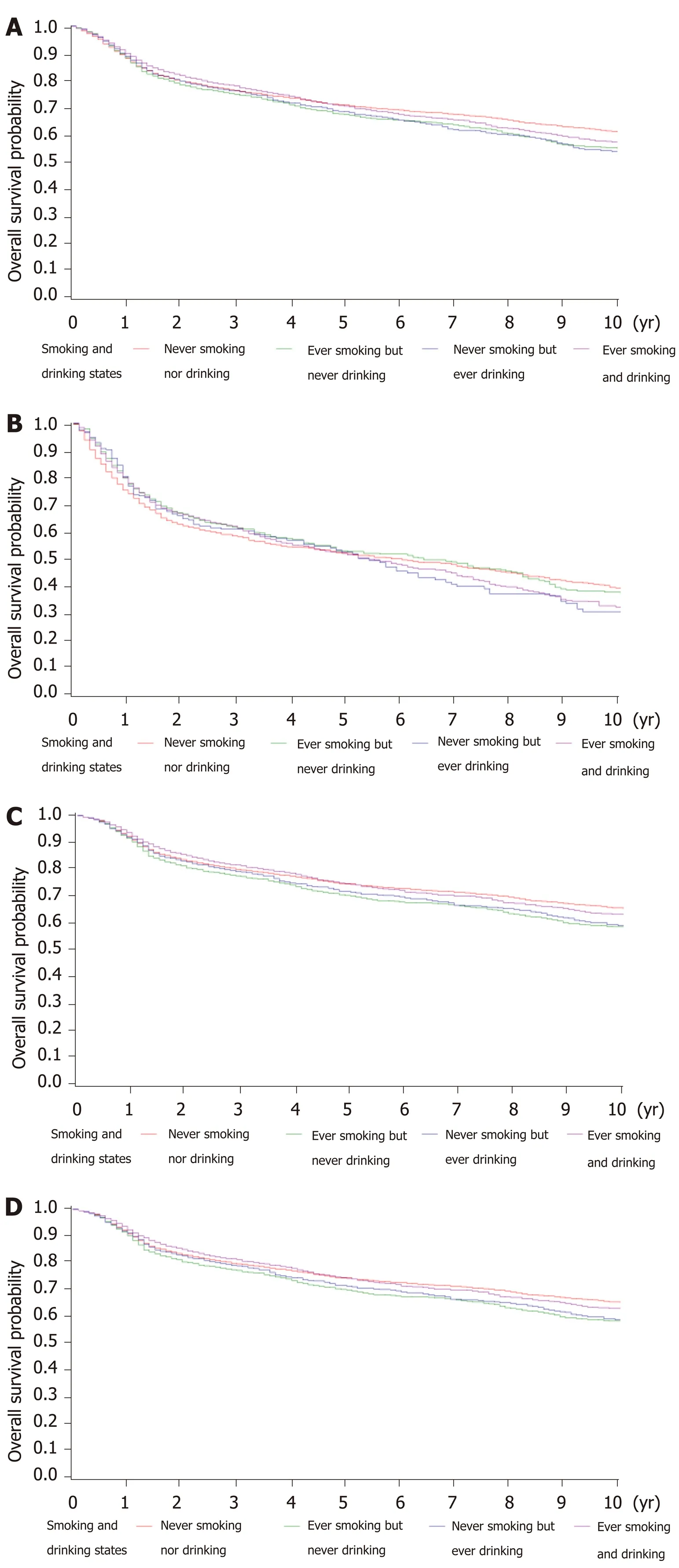

Kaplan-Meier survival comparisons (Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 2) showed no association between smoking status and the OS of gastric cancer patients, even stratified in the only curative gastrectomy group. With regard to alcohol drinking, there was a significant difference between drinking status among no surgery patients (P= 0.009), but not in the other groups (Supplementary Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 3). Survival of those with both smoking and alcohol drinking status was also analyzed (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 4), and significant differences were observed in the total and gastrectomy groups.

Univariate analysis (Supplementary Table 5) showed that overweight and obese patients had better survival than those with normal weight (HR = 0.92, 95%CI: 0.88-0.96,P< 0.001 and HR = 0.89, 95%CI: 0.83-0.96,P= 0.001, respectively), while the discrepancy in survival rate was attenuated in the gastrectomy group (HR = 0.95,95%CI: 0.90-1.00,P= 0.04 and HR = 0.91, 95%CI: 0.84-0.99,P= 0.03, respectively).However, for curative gastrectomy patients, only the overweight group showed an improved survival (HR = 0.94, 95%CI: 0.89-1.00,P= 0.049). Weight loss of > 10% of the usual weight was a significant risk factor for mortality in the four groups (P<0.001). As shown in Table 2, smoking history of more than 30 years was a prognostic factor of poor survival for total patients and gastrectomy patients (P< 0.001).However, drinking status, even heavy drinking, was not a negative prognostic indicator.

Figure 2 Kaplan-Meier survival curves for overall survival of patients with a different body mass index at diagnosis. A: Total gastric cancer patients; B: No surgery patients; C: Gastrectomy patients; D: Only curative gastrectomy patients. BMI: Body mass index.

Survival outcomes in multivariable analysis

The J-shaped relationship between BMI at diagnosis and survival in patients after multivariate-adjusted analysis of different gastrectomy groups is shown in Figure 4.The HR for total gastric cancer patients was the lowest (HR = 0.90; 95%CI: 0.86-0.94) at a BMI of 25.96, followed by a BMI of 28.20 for no surgery patients, 25.47 for gastrectomy patients, and 25.50 for only curative gastrectomy patients. However, the multivariable results (Table 2) indicated that BMI at diagnosis did not affect prognosis.

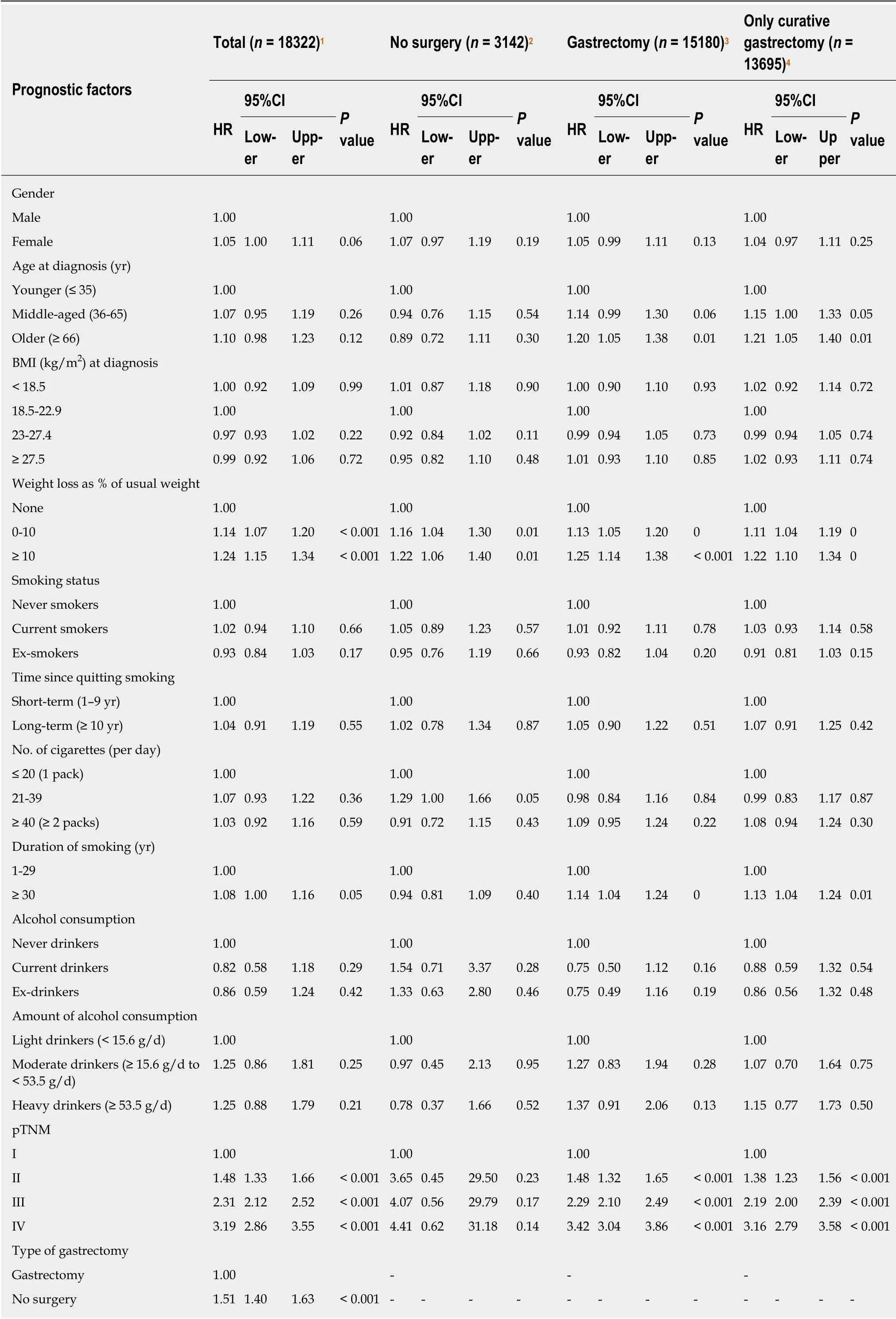

Table 2 Multivariate survival analysis

For total gastric cancer patients, any weight loss (P< 0.001), advanced pTNM stage(P< 0.001), and gastrectomy status (HR = 1.51, 95%CI: 1.40-1.63,P< 0.001) were independently associated with mortality. In the surgery group, factors independently associated with poor survival included older age (≥ 66 years) (HR = 1.20, 95%CI: 1.05-1.38,P= 0.001), any weight loss (0 to 10%, HR = 1.13, 95%CI: 1.05-1.20,P< 0.001 and >10%, HR = 1.25, 95%CI: 1.14-1.38,P< 0.001), smoking history more than 30 years (HR= 1.14, 95%CI: 1.04-1.24,P= 0.004), and advanced pTNM stage (P< 0.001). An additional mortality-related factor for the only curative gastrectomy group was middle age (36-65 years) (HR = 1.15, 95%CI: 1.00-1.33,P= 0.047).

DISCUSSION

This retrospective study investigated how lifestyle factors in gastric cancer patients were associated with prognosis, including BMI at diagnosis, smoking, and drinking status. A primary finding of this study was that BMI at diagnosis was not independently associated with long-term survival after adjusting for risk factors,although weight loss of both 0 to 10% and > 10% of their usual weight were adverse prognostic factors in gastric cancer patients.

We included 18441 patients in this study, a larger cohort than most previous studies, and followed them for more than ten years. Four subgroups, total patients, no surgery, gastrectomy, and only curative gastrectomy, were analyzed to eliminate the effect of gastrectomy which may affect the survival outcomes. After controlling confounding variables, it was found that percentage weight loss of the usual weight was associated with an increased risk of mortality in gastric cancer patients compared to those without weight loss. It is possible that human adipose tissue may have the function of preserving nutrients and increase the chance of survival when the human body suffers stress, such as anti-cancer treatment[6,33,34]. Weight loss may be due to gastric cancer-induced dysphagia, odynophagia, anorexia or cancer cachexia, thus it has a negative effect on survival[35].

Weight management strategies for gastric cancer patients have attracted a lot of attention; however, the relationship between obesity and cancer prognosis is complex.Many previous retrospective studies have also evaluated the association between BMI and the prognosis of gastric cancer in the general population; however, most of these studies only analyzed patients with gastrectomy. A recent study[6]from Korea, which included a cohort of 7765 patients in a single institution, noted that patients who were overweight or mild-to-moderately obese (BMI 23 to < 30 kg/m2) preoperatively had better OS than those with healthy weights. This result was similar to that in another study carried out in Japan, which included 7925 patients[8]. The reasons for the above outcomes may be due to the following: Primarily, it is more likely that obese patients who have suffered gastric cancer have less aggressive tumors[36,37], which is consistent with the features in our study,i.e. the occurrence of pTNM IV tumors was more common in underweight patients. Furthermore, patients who were overweight or obese could achieve an ideal BMI after gastrectomy, thus acquiring better long-term prognosis[37]. Also, a prospective study[38]involving 1033 patients showed that among patients of 60 and older that lower BMI was associated with all-cause death,displaying a J-shaped pattern (HR= 2.28 for BMI < 18.5; HR = 1.61 for 25vs23.0 to <25.0 kg/m2). Conversely, higher BMI was also reported to promote the peritoneal dissemination of gastric cancer and had a worse survival rate[17]. In summary, the clinical analysis mainly concluded that obesity was associated with improved survival of patients with gastric cancer. McQuadeet al[39]indicated that high BMI cancer patients had improved response and survival following treatment with targeted therapy and checkpoint blockade immunotherapy, although a mechanistic link was not elucidated[39,40].

Research targeting the tumor microenvironment also investigated the impact of obesity on immune responses during cancer progression and therapy[41-43]. Trevellinet al[44]reported that esophageal peritumoral adipose tissue and its secretion of tumorpromoting factors are directly correlated with increased tumor growth. One study cultured periprostatic and subcutaneous adipose tissue with prostate cancer cells and concluded that periprostatic adipose tissue in obese individuals provided a favorable environment for prostate cancer progression[45]. Adipocytes undergoing lipolysis were recognized as a source of lipids for cancer cells[46]. Furthermore, a recent study published in Nature Medicine demonstrated that obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) resulted in immune aging, tumor progression and PD-1-mediated T cell dysfunction across multiple species and tumor models[43]. However, in our clinical study, BMI at diagnosis was not independently associated with long-term survival in multivariable analyses, even in the stratified gastrectomy group. Further investigations are needed to clarify the paradoxical effects of obesity between clinical and basic research in future studies.

Figure 3 Kaplan-Meier survival curves for overall survival of patients with a history of both smoking and drinking. A: Total gastric cancer patients; B: No surgery patients; C: Gastrectomy patients; D: Only curative gastrectomy patients.

Figure 4 Body mass index at diagnosis and overall survival in multivariate-adjusted analysis. A: Total gastric cancer patients; B: No surgery patients; C:Gastrectomy patients; D: Only curative gastrectomy patients. BMI: Body mass index.

Evidence on the prognostic effect of drinking has been inconsistent. A metaanalysis of 6856 cases from 7 countries showed that drinkers had a lower survival rate, although there was significant heterogeneity among the seven studies included[47]. Our study revealed no significant association between drinking status and long-term prognosis, even in the subgroup of heavy drinkers (≥ 53.5 g/d). These differences may be partly attributed to the genetic distinction of populations with different race and from different regions.

It was found that cigarette smoking was related to gastric cancer risk[22,23,48], and may also have effects on prognosis. It has been demonstrated in most studies that smoking has a null or inverse influence on OS[25-27,49]. Minamiet al[24]reported a clear association between starting smoking at an earlier age and prognosis. A possible explanation for this is that smoking increases serum estrogen metabolites, which have been postulated to induce a more aggressive tumor at a younger age. Moreover, it has been reported in two published studies[24,31]that the risk of death caused by cancer increases if the patients undergoing curative gastrectomy have a smoking history. This was comparable with our research. In our multivariable analysis, we found that smoking history of more than 30 years conferred a worse prognosis in both the gastrectomy and curative gastrectomy groups. This may indicate that long-term cigarette smoking has a significant effect on the risk of mortality in patients who underwent gastrectomy. Although the cause of this association is unclear, it is possible that smoking has an adverse effect on the pulmonary, circulatory, and immunologic systems, and on wound healing[32,50]. The cumulative chronic toxic effects of long-term smoking may delay the recovery of gastrectomy patients with reduced body condition and cause poor survival outcomes.

Several limitations need to be considered in this study. Firstly, we do not have data on changes in lifestyle factors during treatment, or in the post-treatment phase. These measures collected systematically would allow for a better understanding of whether change following diagnosis is associated with cancer prognosis. Secondly, BMI has been used as the most common measure of indicating obesity due to its simplicity of measurement and availability. However, waist circumference and actual body composition, particularly fat and muscle percentages, may be more reflective of the degree of obesity. Thirdly, the study was conducted in a single institution; therefore,the results might not be used as a reference for the whole Chinese population.However, the results may provide a reference value as the number of gastric cancer patients was large, and the patients were from Northern and Eastern areas in China.The strength of this study is that the groups analyzed included total patients, no surgery, gastrectomy and curative gastrectomy groups.

In conclusion, our results contribute to a better understanding of lifestyle factors on the overall burden of gastric cancer with regard to long-term prognosis. Among the total patients, weight loss (both the 0 to 10% and > 10% groups) but not BMI at diagnosis was related to survival outcomes. Other factors, such as smoking history of more than 30 years conferred a worse prognosis only in patients who underwent gastrectomy. Extensive efforts are needed to elucidate mechanisms targeting the complex effects of lifestyle factors.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- SARS-COV-2 infection (coronavirus disease 2019) for the gastrointestinal consultant

- Optimized timing of using infliximab in perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease

- Intestinal epithelial barrier and neuromuscular compartment in health and disease

- Gastrointestinal cancer stem cells as targets for innovative immunotherapy

- Is the measurement of drain amylase content useful for predicting pancreas-related complications after gastrectomy with systematic lymphadenectomy?

- Silymarin, boswellic acid and curcumin enriched dietetic formulation reduces the growth of inherited intestinal polyps in an animal model