Inflammatory niche:Mesenchymal stromal cell priming by soluble mediators

2020-04-30

Aleksandra Jauković, Tamara Kukolj, Hristina Obradović, Ivana Okić-Đorđević, Slavko Mojsilović,Diana Bugarski, Laboratory for Experimental Hematology and Stem Cells, Institute for Medical Research, University of Belgrade, Belgrade 11129, Serbia

Abstract Mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (MSCs) are adult stem cells of stromal origin that possess self-renewal capacity and the ability to differentiate into multiple mesodermal cell lineages.They play a critical role in tissue homeostasis and wound healing, as well as in regulating the inflammatory microenvironment through interactions with immune cells.Hence, MSCs have garnered great attention as promising candidates for tissue regeneration and cell therapy.Because the inflammatory niche plays a key role in triggering the reparative and immunomodulatory functions of MSCs, priming of MSCs with bioactive molecules has been proposed as a way to foster the therapeutic potential of these cells.In this paper, we review how soluble mediators of the inflammatory niche(cytokines and alarmins) influence the regenerative and immunomodulatory capacity of MSCs, highlighting the major advantages and concerns regarding the therapeutic potential of these inflammatory primed MSCs.The data summarized in this review may provide a significant starting point for future research on priming MSCs and establishing standardized methods for the application of preconditioned MSCs in cell therapy.

Key Words:Mesenchymal stem cells; Pro-inflammatory cytokines; Alarmins; Priming;Boosting the therapeutic potential

INTRODUCTION

Inflammation is a localized immunologic response of the tissue elicited by harmful stimuli, including pathogens, irritants, or physical injury.This complex and protective response plays a fundamental role in the regulation of tissue repair, serving to eliminate harmful stimuli and begin the healing process[1].In fact, inflammation is considered an important initial phase, followed by cell proliferation and extracellular matrix remodeling.These phases overlap over time and each of them represents a sequence of dynamic cellular and biochemical events, contributing to tissue regeneration through the collaboration of many cell types and their soluble products[2].Immune cells, together with blood vessels, various stromal cells,extracellular matrix components, and a plethora of secreted soluble mediators,comprise an inflammatory microenvironment capable of inducing different responses of cells within injured tissue[3].

Soluble mediators released from injured/necrotic cells or damaged microvasculature lead to enhanced endothelium permeability and infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages.Among these mediators are endogenous danger signals, known as alarmins, which are rapidly released by dying necrotic cells upon tissue damage and play an important role in promoting and enhancing the immune response[4-6].To date, the best-characterized alarmins are the interleukin (IL)-1 family of cytokines (IL-1α and IL-33), high-mobility group protein B1 (HMGB1), S100 proteins, and heat shock proteins (Hsps)[4,7].In addition, during the inflammatory process, the phagocytosis of necrotic cells by resident/recruited neutrophils and macrophages induces the release of various inflammatory factors, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interferon (IFN)-γ, IL-1β, IL-17, and chemokines[8].

Aside from numerous soluble mediators, tissue injury mediated by immunity or infection involves an even greater number of various immune cells, including B cells,CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and natural killer cells.While all immune cells play key roles in wound healing through the eradication of damaged tissue and invading pathogens,their excessive activation can actually aggravate the injury.Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of inflammatory niche elements might contribute to the development of novel therapeutic strategies for the treatment of inflammatoryassociated diseases, as well as conditions of failed tissue regeneration.

One of the cellular compartments participating in the inflammatory niche represents mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (MSCs).MSCs are stem cells of stromal origin that possess self-renewal capacity and the ability to differentiate into three mesodermal cell lineages, including osteocytes, chondrocytes, and adipocytes[9].Considering their critical role in tissue homeostasis and wound healing, MSCs have garnered great attention as promising candidates for tissue regeneration.Although first isolated from the bone marrow (BM)[10], MSCs may be obtained from various fetal and adult tissues,such as the umbilical cord (UC), peripheral blood, adipose tissue (AT), and skin and dental tissues[11,12].According to the minimum criteria proposed by the International Society for Cellular Therapy, MSCs originating from different tissues are evidenced by the property of plastic adherencein vitroand expression of various non-specific surface molecules, such as cluster of differentiation (CD)105, CD90, CD73, and CD29,in parallel with trilineage differentiation potential[13].However, the term MSC has recently been considered inappropriate, as it has become clear that MSCs from different tissues are not the same, especially with respect to their differentiation capacities[14,15], whereas their multipotent differentiation potential has not been confirmed inin vivoconditions.Therefore, Caplan[17]recently proposed this term to stand for medicinal signaling cells[16], indicating the correlation of the therapeutic benefits of MSCs with the secretion of various bioactive molecules.

Many studies have demonstrated that MSCs contribute to tissue repair by accumulating at sites of tissue damage and inflammation, where together with resident MSCs, they exert reparative effects in two ways.One way is to replace damaged cells through differentiation, and another is related to the ability of MSCs to strongly influence the microenvironment by releasing bioactive factors and interacting with multiple cell types[18,19].Indeed, poorly immunogenic MSCs that weakly express major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and lack MHC class II play a critical role in regulating the inflammatory microenvironment through interactions with immune cells such as T cells, B cells, natural killer cells, and dendritic cells[20-22].As a result of these interactions, MSCs suppress lymphocyte proliferation and maturation of monocytes into dendritic cells, while stimulating the generation of regulatory T cells(Tregs) and M2 macrophages[23,24].

The major role in the crosstalk between MSCs and immune cells has been ascribed to soluble factors, which upon release by activated immune cells, significantly affect MSCs paracrine activity, conversely influencing immune cells.In particular, the immunosuppressive activity of MSCs has been related to the production of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), nitric oxide (NO), prostaglandin-E2 (PGE2), IL-10,transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, and TNFα-stimulated gene-6[25].

Inflammatory priming of MSCs

It is believed that the inflammatory niche plays a key role in triggering the reparative function of MSCs.Namely, studies have demonstrated that the immunosuppressive potential of MSCs is not inherently expressed but requires priming by inflammatory factors, including IFN-γ, TNF-α, or IL-1β[18,26].Moreover, it has been found that MSCs can polarize into MSC type 1 with a pro-inflammatory profile or MSC type 2 with an immunosuppressive phenotype, depending on the inflammatory condition[23,27].On the other hand, the inflammatory microenvironment influences the differentiation potential of resident and recruited MSCs, significantly impairing their regenerative capacity.In addition, several studies have shown that MSCs of different tissue origin may exert differential sensitivity to inflammatory conditions[28,29].These data point to the critical importance of interactions between MSCs and inflammatory factors for the outcome of wound healing.

Indeed, the regenerative potential of transplanted MSCs is affected by inflammatory conditions[30], indicating the strong influence of the recipient’s inflammatory status on the efficacy of MSC-based therapies.Interestingly, to reduce the heterogeneity of MSCs and generate more homogenous therapeutic products, MSC priming with cytokines has been proposed[31].The application of bioactive molecules in this context has been considered a supplemental molecular signal used to foster the therapeutic potential of MSCs and contribute to establishing a favorable microenvironment for tissue repair.

The complex cytokine network has been considered a critical part of the inflammatory microenvironment, where the pleiotropic properties of proinflammatory cytokines play a decisive role in the healing process and tissue regeneration.TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1, IL-17, and IL-6 are the most common inflammatory cytokines in this complex network[32].Moreover, another significant constituent of the inflammatory niche considers alarmins, such as IL-1α and IL-33, HMGB1, S100 proteins, and Hsps, which can promote the immune response, thereby supporting host defense and tissue repair[7].Here, we review how these soluble mediators of the inflammatory niche influence the regenerative and immunomodulatory potential of MSCs, highlighting the major advantages and concerns regarding the therapeutic potential of inflammatory primed MSCs.

MSCs priming with pro-inflammatory cytokines

IFN-γ priming:One of the most studied inflammatory priming mediators is IFN-γ,which is a key player in cellular immunity regulation, heightening immune responses in infection and cancer.However, very little is known about the effects of IFN-γ on the regenerative potential of MSCs.Namely, Croitoru-Lamouryet al[33]demonstrated that IFN-γ exerts significant antiproliferative effects on mouse and human BM-MSCs(Figure 1) through IDO induction and production of downstream tryptophan metabolites, such as kynurenine, which can potentiate the suppressive effects on cell proliferation in an autocrine manner.This was the first study that linked IFN-γinduced IDO with the control of MSC differentiation potential, as evidenced by the inhibition of both osteogenic and adipogenic marker expression in IFN-γ-primed BMMSCs upon induction of differentiation.

Figure 1 Influence of inflammatory priming on regenerative features of mesenchymal stromal/stem cells under in vitro conditions.

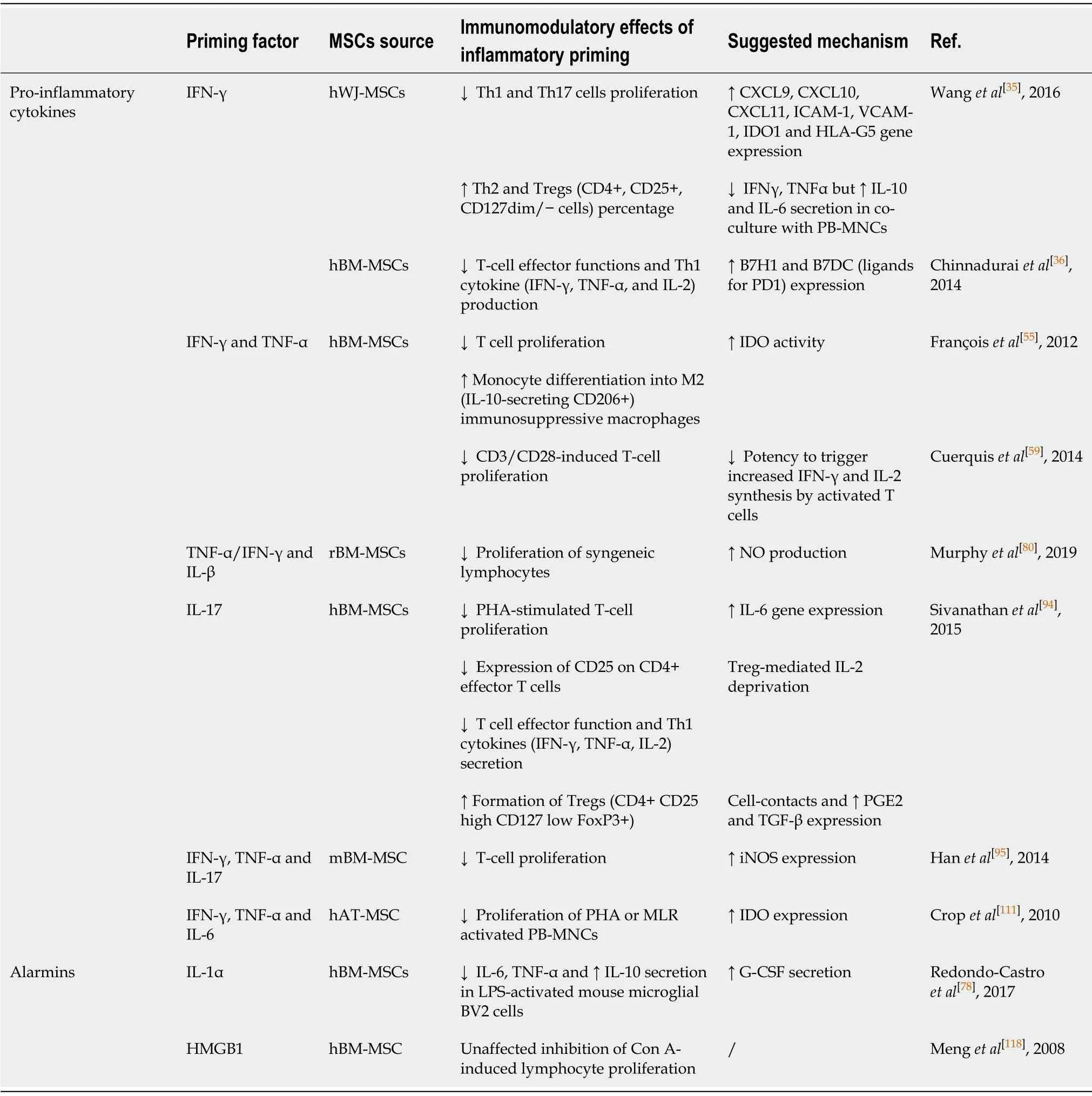

Numerous studies have demonstrated that the priming of MSCs with IFN-γ can enhance the immunosuppressive property of these cells by IDO stimulation[34].In addition, exposure to IFN-γ has been shown to induce UC Wharton’s jelly (WJ)-MSCs to express other immunosuppressive factors, such as human leukocyte antigen G5, as well as C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL)9, CXCL10, and CXCL11[35].Even more,IFN-γ-primed WJ-MSCs secrete more IL-6 and IL-10 upon co-culture with activated lymphocytes, increasing the percentage of Tregs, while decreasing the frequency of T helper (Th)17 cells (Table 1).

Another mechanism underlying the inhibitory effects of IFN-γ-primed BM-MSCs on T-cell effector functions is the upregulation of programmed death-ligand 1 (referred to as PD-L1)[36](Table 1).However, in the context of potential MSCs’ therapeutic use, the findings from several studies which have demonstrated that MSCs priming with IFN-γ led to upregulation of class I and class II human leukocyte antigen (referred to as HLA) molecules should be considered, as they indicated more immunogenic MSCs profile that is linked to a higher susceptibility to host immune cells recognition[37,38].Noteworthy, a recent study found that priming with IFN-γ did not increase HLA class II expression on senescent BM-MSCs but upregulated this molecule on early passage BM-MSCs, suggesting that IFN-γ priming effects can also be influenced by cell aging[39].

Interestingly,in vivoexperiments have demonstrated that IFN-γ affects the therapeutic efficacy of MSCs in a dose-dependent manner.Namely, when low concentrations of IFN-γ were used for murine BM-MSCs priming, the therapeutic effects of MSCs on experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice were completely inhibited, as demonstrated by the increased secretion of pro-inflammatory chemokine CCL2 and higher expression of MHC molecules class I and II[38].BM-MSCs primed with higher concentrations of IFN-γ prior to use in murine models of colitis reportedly increase MSC therapeutic efficacy, as demonstrated by the significantly attenuated development and/or reduced symptoms of colitis[40].These effects werefound to be related to the increased migration of IFN-γ-primed MSCs along with their enhanced capacity to inhibit Th1 inflammatory responses, all of which contributed to decreased mucosal damage.In addition, Polchertet al[41]showed that IFN-γ-primed mouse BM-MSCs suppress graftvshost disease more efficiently than non-primed MSCs depending on the magnitude of IFN-γ exposure (Figure 2).By contrast, a recent study showed that infusion of thawed IFN-γ-primed human MSCs failed to improve retinal damage in a murine model of retinal disease[42].

Table 1 Influence of inflammatory priming on immunomodulatory features of mesenchymal stromal/stem cells under in vitro conditions

Figure 2 Improved in vivo therapeutic potential of inflammatory primed mesenchymal stromal/stem cells.

TNF-α priming:TNF-α is a pleiotropic cytokine involved in systemic inflammation,which also affects the metabolism, growth, and differentiation potential of various cell types.Regarding the regenerative potential of TNF-α-treated MSCs, it has been determined that this cytokine promotes the proliferation of human synovial MSCs and BM-MSCs[43,44], while not affecting their clonogenic potential.Moreover, the involvement of the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathway is implicated in TNF-α-stimulated invasion and proliferation of BM-MSCs[44](Figure 1).Furthermore,the preconditioning of MSCs with TNF-α differentially regulates their chondrogenic differentiation depending on the tissue source and donor age (Figure 1).Namely,while TNF-α does not affect the chondrogenic capacity of human synovial MSCs and BM-MSCs[43,45], Wheilinget al[46]revealed that it inhibited the chondrogenesis of human BM-MSCs isolated from elderly donors.In addition, several studies have indicated that TNF-α alters the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs in dose-, tissue source-, and species-specific manners (Figure 1).Regarding rodent MSCs, several studies have found that TNF-α inhibits the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs[47,48], while continuous delivery of TNF-α stimulates the osteogenic differentiation of rat BM-MSCs seeded onto three-dimensional biodegradable scaffolds[49].The enhanced osteogenic potential has also been evidenced for human BM-MSCs treated with TNF-α[50,51].However, it dually affects dental pulp stem cells, promoting their osteogenic differentiation through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, while suppressing the osteogenesis of these cells at high concentrations[52,53].

In the context of the stronger immunomodulatory capacity of TNF-α-primed MSCs,studies have demonstrated increased secretion of the immunosuppressive molecules PGE2 and IDO, chemokine IL-8, CXCL5, CXCL6, and certain growth factors such as hepatocyte growth factor, insulin-like growth factor 1, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)[54-57](Table 1).Moreover, it has been revealed that TNF-α priming of rat UC-MSCs suppresses the inflammatory milieu by increasing TGF-β and IL-10 expression[58].Because the immunosuppressive effects of TNF-α are less pronounced compared to IFN-γ priming in WJ-MSCs[28], several studies have investigated the combined effects of TNF-α and IFN-γ on the immunomodulatory potential of MSCs.Indeed, when human BM-MSCs were subjected to combined pretreatment with TNF-α plus IFN-γ, more effective inhibition of CD3/CD28-induced T-cell proliferation was observed compared to non-primed MSCs[59](Table 1).Also,combined TNF-α and IFN-γ preconditioning was shown to increase IDO activity in BM-MSCs, resulting in monocyte differentiation into M2 immunosuppressive macrophages, which further inhibited T-cell proliferationviaIL-10 secretion[55].

Regarding the beneficial effects of MSC preconditioning with TNF-α, anin vivostudy performed by Suet al[60]showed that the culture medium of TNFα-primed mouse BM-MSCs reduced experimental allergic conjunctivitis through multiple cyclooxygenase-2-dependent antiallergic mechanisms.In addition, the culture medium of TNF-primed human AT-MSCs has been shown to accelerate cutaneous wound closure, angiogenesis, and infiltration of immune cells in a rat excisional wound modelviaIL-6 and IL-8 secretion[61].Also, in a model of mouse myocardial infarction, improved cardiac function related to decreased inflammatory responses and reduced infarct size has been documented in animals receiving TNF-α-primed human BM-MSCs[62].By contrast, TNF priming reverses the immunosuppressive effects of mouse MSCs on T-cell proliferation, resulting in the failure of MSC treatment of murine collagen-induced arthritis[63].

IL-1β priming:IL-1β is the key mediator of inflammatory responses, which contributes to the host-defense response facilitating activation of innate immune cells[64].Regarding the effects of IL-1β priming on MSCs proliferation and differentiation,heterogeneous results have been reported (Figure 1).Namely, while IL-1β preconditioning increases equine AT-MSCs and human synovium-derived MSCs proliferation[65,66], exposure of UC-MSCs to IL-1β results in suppressed proliferation[67].Moreover, functional analyses of human BM-MSCs have revealed that treatment with IL-1β does not affect the proliferation of these cells, and promotes their migration and adhesion to extracellular matrix components[68].Also, a study by Guoet al[69]demonstrated that IL-1β promoted UC-MSCs transendothelial migration through the CXCR3-CXCL9 axis, indicating the beneficial effects on MSC homing to target sites.

Many studies have described the modulatory effects of IL-1β stimulation on the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs, with conflicting results depending on the MSC tissue origin as well as IL-1β concentration (Figure 1).Sonomotoet al[70]demonstrated the ability of IL-1β to induce the osteogenic differentiation of human BM-MSCsviathe Wnt pathway.Increased osteogenesis has also been found for equine AT-MSCs and human UC-MSCs treated with IL-1β[65,67].On the other hand, depending on the concentration, IL-1β exerts dual effects on the osteogenesis of periodontal ligament-MSCs, since low doses of IL-1β promote osteogenesis by activating the bone morphogenetic protein (referred to as BMP)/Smad signaling pathway, while higher doses of the cytokine impede osteogenesis[71].IL-1β treatment also inhibits the chondrogenesis of MSCs from the femoral intramedullary canal in a dose-dependent mannerviaNF-κB activation[46].In accordance with these findings, decreased chondrogenic differentiation has been reported for BM-MSCs and synovial fluid-MSCs treated with IL-1β[72-75].However, Hingertet al[76]showed that pretreatment of BMMSCs with IL-1β followed by BMP-3 stimulation in a three-dimensionalin vitrohydrogel model resulted in high proteoglycan accumulation and SRY-box transcription factor 9 expression, suggesting that IL-1β may be the causative factor.

Several studies have indicated changes in the secretory profile of MSCs primed with IL-1β, as well as the significance of IL-1β priming in combination with other factors.Regarding gingival-MSCs, IL-1β preconditioning induces the expression of TGF-β and matrix metalloproteinase agonists[77], while in human BM-MSCs, IL-1β increases granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (referred to as G-CSF)[78], IL-6, VEGF, CXCL1,and CCL2 chemokines[79].The immunosuppressive activities of rat BM-MSCs were shown to be significantly promoted after preconditioning with TNF-α or IFN-γ in combination with IL-β, as the decreased proliferation of syngeneic lymphocytesin vitrowas demonstrated[80](Table 1).These effects were confirmed byin vivoexperiments in a rat cornea transplant model, where after transplantation of syngeneic MSCs primed with TNF-α/IL-β enhanced graft survival (up to 70%) was observed compared to unprimed MSCs (up to 50%).In addition, the increased number of Tregs and reduced expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the draining lymph node of these animals were found, whereas there was an increased number of regulatory monocyte/macrophage cells and Tregs in the lungs and spleen[80].

Administration of IL-β-primed human UC-MSCs in mice with dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis also increases the number of Tregs and Th2 cells, while reducing Th1 and Th17 cells in the spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes[81].A recent study by Yuet al[82]emphasized the role of PGE2 and IDO induction in the observed immunosuppressive effects of umbilical cord blood-MSCs primed with IL-1β and IFNγ in the same disease model.Moreover, another recent study showed that the culture medium of IL-1β-primed AT-MSCs increased the phagocytic capacity of neutrophils,which may contribute to inflammation resolution, removal of tissue debris, and support of tissue repair in joint pathology[83].Overall, the results indicating the immunosuppressive phenotype of IL-1β-primed MSCs strongly suggest that this cytokine might promote the therapeutic efficacy of MSCs in disorders related to an exaggerated immune response (Figure 2).

IL-17 priming:IL-17 is another pro-inflammatory cytokine that plays a pivotal role in linking the immune and hematopoietic systems, while also contributing to the pathogenesis of numerous autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.However, the effects that this cytokine exerts on MSCs are still not fully understood.To date, it has been shown that IL-17 stimulates the proliferation of mouse and human BM-MSCs, as well as the migration of human BM-MSCs and trans-endothelial migration of peripheral blood MSCs[84-86](Figure 1).Regarding the differentiation potential,published results have shown that IL-17 priming enhances osteogenic[84,87-89], but inhibits chondrogenic[90]and adipogenic[88,91]differentiation in human BM-MSCs.Moreover, IL-17 can decrease the osteogenic differentiation of periodontal ligament-MSCs through extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases 1 and 2 (referred to as ERK1/2), and c-Jun N-terminal kinase mitogen-activated protein kinases[92].Research related to the effects of IL-17 on the differentiation potential of mouse BM-MSCs has led to conflicting results, as one study found that IL-17 did not affect the differentiation potential of MSCs towards osteoblasts[85], whereas another showed suppressed osteogenic differentiation of these cells mediated by IκB kinase and NF-κ B[93].

Regarding the immunomodulatory activity of MSCs, IL-17 priming enhances the immunosuppressive features of MSCs.While IL-17 has no impact on MSC markers and the low immunogenic phenotype of human BM-MSCs, IL-17-primed MSCs suppress T-cell proliferation and inhibit CD25 expression and expression of Th1 cytokines, including IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2[94].Moreover, a study showed that mouse MSCs pretreated with IFN-γ and TNF-α in combination with IL-17 significantly reduced T-cell proliferationviathe inducible nitric oxide synthase (referred to as iNOS) pathway[95](Table 1).The same study confirmed the immunosuppressive activity of BM-MSCs primed with IL-17in vivoin a mouse model of concanavalin Ainduced liver injury.However, another study showed that IL-17 significantly reduced the suppressive capacity of olfactory ecto-MSCs on CD4+ T cells, mainly through the downregulation of suppressive factors (PD-L1, iNOS, IL-10, and TGF-β)[96].The positive effect of IL-17 on the immunomodulatory features of MSCs has been confirmed inin vivostudies with different animal models.Namely, in a study in which mouse BM-MSCs were treated with IL-17 prior to their use in ischemia-reperfusion acute kidney injury, a significant decrease in IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ levels and higher spleen and kidney Treg levels were shown compared to mice that received nonprimed MSCs[97].In another work, IL-17-primed mouse BM-MSCs used in a skin transplantation model were found to increase the Treg subpopulation as well as IL-10 and TGF-β levels, significantly prolonging graft survival[98].

IL-6 priming:Pleiotropic effects on immune regulation, hematopoiesis, and tissue regeneration are exerted by another inflammatory cytokine, IL-6[99].Preconditioning MSCs with IL-6 has been shown to influence their behaviors in different manners depending on the tissue origin of the MSCs (Figure 1).Namely, a few studies have reported conflicting data showing that IL-6 has no effect on the proliferation of human AT-MSCs and mouse BM-MSCs[100,101], whereas in other studies, IL-6 increased the proliferation of human placenta-derived MSCs and BM-MSCs[102,103].Moreover, the stimulating effect of IL-6 on BM-MSCs growth andin vitrowound healing is mediated by ERK1/2 activation[103].It has also been reported that IL-6 differentially influences stem cell differentiation (Figure 1).Priming with IL-6 under osteogenic induction conditions has been shown to enhance mineralization and alkaline phosphatase expression in human BM-MSCs, AT-MSCs, and stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (called SHEDs)[104-107].However, studies using lower concentrations of IL-6 have shown no effect on osteogenic differentiation potency of human BMMSCs[103].Although IL-6 inhibits the chondrogenic differentiation of human BM-MSCs when added during differentiation induction[103], concomitant supplementation with IL-6 and soluble IL-6 receptor contributes to the enhanced chondrogenesis of this type of MSC[108].Treatment with IL-6 during or prior to adipogenic differentiation induction reduces the adipogenesis capacity of human BM-MSCs[103], while other studies have reported no or positive effects of IL-6 on the adipogenic ability of human BM-MSCs,AT-MSCs, and SHEDs[104,109,110].

Even less is known about the immunomodulatory potential of IL-6-preconditioned MSCs.In this context, few studies have analyzed IL-6 effects in combination with other pro-inflammatory cytokines.Namely, altered immunological status has been reported for AT-MSCs primed with a combination of IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-6 (Table 1), as shown by the upregulated expression of HLA class I and class II, as well as CD40[111],indicating a potentially more immunogenic phenotype.In addition, although the same priming conditions have no effect on AT-MSCs differentiation capacity, they enhance their immunosuppressive activity mainly through increased IDO expression.Another study demonstrated that human AT-MSCs and BM-MSCs primed with another combination of pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-23, exerted increased differentiation potential towards osteogenic and adipogenic lineages, while their morphology, immunophenotype (except upregulated CD45), and costimulatory molecule expression were similar to non-primed cells.Also, primed MSCs showed increased TGF-β and decreased IL-4 production, while their suppressive effect on Tcell proliferation was comparable to controls[112]Although these findings suggest that priming with IL-6 might promote the therapeutic efficacy of MSCs in the treatment of various inflammatory and autoimmune disorders, no study investigating thein vivotherapeutic potential of MSCs preconditioned with IL-6 (alone or combined with other cytokines) has been performed to date.

MSCs priming with alarmins

Alarmins are constitutively expressed inside cells and exert various functions under physiological conditions.Upon tissue damage induced by pathogens or physical/chemical injuries, dying necrotic cells passively and rapidly release alarmins outside of cells to promote the immune response and support tissue repair[4,5,6].In addition to these activities, alarmins are involved in many other processes, such as cellular homeostasis, wound healing, and tumor development[6,7].The bestcharacterized alarmins, such as IL-1α, IL-33, HMGB1, S100 proteins, and Hsps, will be discussed here in the context of their effects on MSC biology and potential role in tissue repair.

IL-1α and IL-33 are both dual-function cytokines that are localized in the nucleus under homeostatic conditions, where they function as transcription factors.Data on their extracellular effects on MSCs are very elusive.It has been demonstrated that IL-1α stimulates the expression of trophic factor G-CSFviaIL-1 receptor type 1 signaling in human BM-MSCs.In addition, the conditioned medium of IL-1α-primed BM-MSCs was shown to inhibit the secretion of inflammatory and apoptotic markers in lipopolysaccharide-activated mouse microglial BV2 cells and increase secretion of the anti-inflammatory IL-10 cytokine[78], suggesting that MSCs priming with IL-1α favors their immunosuppressive activities (Table 1).Another recent study showed that IL-1α decreased the proliferative and adipogenic differentiation capacity of AT-MSCs,whereby adipogenesis was inhibited predominantly during the early phase of differentiationviaNF-κB and ERK1/2 pathways with subsequent stimulation of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-8, IL-6, CCL2, and IL-1β, during adipogenic differentiation of AT-MSCs[113](Figure 1).Since the effects of IL-1α are conspicuous at the beginning of the differentiation process, it is important to further examine IL-1α priming in the context of MSC differentiation.It was recently demonstrated that without changing MSC marker expression[114,115], IL-33 treatment has the potential to modify the regenerative[114]and immunomodulatory characteristics of MSCs[115].Our recent study demonstrated that IL-33 treatment reduced periodontal ligament-MSCs and dental pulp MSCs osteogenesis but supported their proliferation, clonogenicity,and stemness (Figure 1).Both MSC types primed with IL-33 maintained their differentiation capacity, while increased alkaline phosphatase activity was also observed, indicating that IL-33 may contribute to the preservation of the dental stem cell pool[114].Research conducted by Terrazaet al[115]demonstrated that IL-33 with IFNγ stimulated the high expression of IL-6, TGF-β, and iNOS in mouse BM-MSCs.Despite the scarce data on IL-1α and IL-33 priming of MSCs, overall data indicate that preconditioning with these molecules should be additionally explored as an MSC priming strategy.

Another nuclear alarmin is HMGB1, a non-histone DNA-binding protein involved in the maintenance of the chromatin structure and gene expression regulation[116].The knowledge on the effects of released HMGB1 on MSCs functions is still contradictory,as its stimulatory[117]as well as inhibitory[118,119]actions on MSCs proliferation have been reported.The promoted migratory capacity of MSCs primed with HMGB1 has also been demonstrated[117-119], indicating its beneficial effects for MSC functional adjustment in therapeutic use.In the presence of HMGB1, the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs is also induced[118,120,121](Figure 1).Moreover, HMGB1 stimulates the secretion of various cytokines by MSCs including macrophage CSF,eotaxin-3, epidermal growth factor receptor, VEGF, angiopoietin-2, CCL-5, urokinase plasminogen activator receptor, and macrophage migration inhibitory factor, which may be associated with the induced osteogenic differentiation under HMGB1 influence[121].Furthermore, in rat BM-MSCs, along with promoted MSC migration,HMGB1 stimulates VEGF-induced differentiation to endothelial cells but decreases their proliferation and platelet-derived growth factor-induced differentiation to smooth muscle cells[119].These findings indicate that HMGB1 priming could be a significant factor in tissue engineering for MSC-guided differentiation.Regarding immunomodulatory functions, it has been reported that HMGB1 priming has no effect on BM-MSCs ability to inhibit the proliferation of concanavalin A-stimulated lymphocytesin vitro[118](Table 1), but additional research is needed to confirm these functions.

Unlike IL-1α, IL-33 and HMGB1 alarmins, S100 proteins, and Hsps are located in the cytoplasm during homeostasis[4].The effect of extracellular S100A6 has been investigated on MSCs derived from WJ of the UC, and the results have shown the ability of this molecule to increase cellular adhesion and reduce their proliferation capacity by interacting with integrin β1[122](Figure 1).Regardless, pretreatment of human AT-MSCs with S100A8/A9 and their subsequent application to wounds induced in C57BL/6 mice significantly improve wound healing due to transcriptome expression profile changes related to the enhanced protective MSCs phenotype[123].Regarding the Hsp protein family, it has been demonstrated that Hsp90 increases viability and protects rat BM-MSCs against apoptosis, simultaneously increasing the paracrine effect of MSCs[124].Another study showed that Hsp90α promotes rat MSCs migration, possibly mediated by the increased secretion of MMPs, SDF-1/CXCR4, and vascular cell adhesion protein 1[125](Figure 1).Interestingly, the dual effects of Hsp70 have been demonstrated depending on the age of the MSCs.Namely, in a study by Andreevaet al[126], Hsp70 increased the growth of aged but not young mouse AT-MSCs(Figure 1), suggesting the potential beneficial effects of Hsp70 priming.Moreover, the important role of Hsp70 in the osteogenesis of human MSCs is demonstrated by increased alkaline phosphatase activity and MSC mineralization[127,128].

CONCLUSION

As MSCs are crucial cellular components for tissue repair, it is essential to understand how the inflammatory microenvironment modulates the functionality of these cells.The beneficial effects of MSCs have been demonstrated, but due to the large heterogeneity detected within MSC populations, the success of their application in clinical trials has been limited.Moreover, it is believed that the inflammatory niche is indispensable for triggering MSC activity in an appropriate manner.Therefore,preconditioning methods have been applied to enhance and/or adjust MSCs functionality, including their regenerative and immunomodulatory status.To date,studies of the MSCs response to soluble factors featuring the inflammatory niche have been mostly focused on the effects provoked during their presence, pointing to the necessity of further exploring the durability of these changes.In this work, we collected data on the therapeutic potential of MSCs treated with pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-17 and IL-6) and alarmins (IL-1α, IL-33, HMGB1,S100 proteins, and Hsps) that are predominantly released at the site of the damaged tissue.

The reviewed data strongly indicate that all aforementioned factors possess the ability to modify the regenerative and immunomodulatory activities of MSCs, and the effects of these factors depend on the MSC tissue and species origin, as well as on donor age and cellular aging (senescence) status.In addition, different effects have been reported depending on the priming factor concentration and their selected combinations, as well as on the disease model, indicating that all of these aspects together should be carefully considered in relation to specific application requirements.Importantly, the effects of primed MSCs have been demonstrated in various animal wound and disease models, suggesting the validity of priming approaches for MSC therapy.Indeed, priming MSCs with certain inflammatory factors, such as TNF-α, IL-β, IFN-γ or S100A8/A9, contribute to the suppression of graftvshost disease and colitis, as well as to improved corneal and skin graft survival,mediated by their dominant immunosuppressive activity (Figure 2).Together, the data summarized in this paper provide a significant starting point for future research on priming MSCs and set future directions for establishing standardized methods for the application of preconditioned MSCs in cell therapy.

杂志排行

World Journal of Stem Cells的其它文章

- Human mesenchymal stem cells derived from umbilical cord and bone marrow exert immunomodulatory effects in different mechanisms

- Mass acquisition of human periodontal ligament stem cells

- Perspectives on mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells and their derivates as potential therapies for lung damage caused by COVID-19

- Stem cell treatments for oropharyngeal dysphagia:Rationale,benefits, and challenges

- Mechanisms of action of neuropeptide Y on stem cells and its potential applications in orthopaedic disorders

- Senescent mesenchymal stem/stromal cells and restoring their cellular functions