收藏史上独树一帜的传奇

2020-04-20陈阳

陈阳

文物篇

《兰亭序》从诞生到传家、从真迹到摹本、从书法到文化,已成为中国书法艺术的图腾,中国古代文化形态的标志。它产生、流传、消失、衍变和传播的历史,已超越了王羲之为代表的魏晋文人风骨和精神世界,成为中国特有的一种艺术文化,并播及海外。

在中国,无分南北西东,不论男女老幼,几乎没有人不知道书圣王羲之之名和《兰亭序》其帖的。

《兰亭序》完成后,一直在王氏一门作为传家之宝,到了唐代,进入皇室内府,又在冯承素、欧阳询、虞世南、褚遂良等书法大家的手中生发出多个摹本、临本。北宋法帖刻石捶拓技术兴起以后,唐人的临摹本又生发出许多上石本,文献记载宋人藏有《兰亭序》传本百种或百种以上的就有好几位,其中贾似道一人就藏有800种。从此兰亭的各种传本进入一团乱麻的阶段。元、明、清三代人也爱《兰亭》,把这一团麻搞得更乱。

唐人摹本、宋人传本、名家临本,加上历代有影响的拓本,《兰亭序》建构起一个庞大驳杂的书法艺术世界,也给我们留下了一大笔因《兰亭序》书法而生发出来的文物遗产。今天我们暂且不去理会这团乱麻,把目光转向书法和碑帖之外,去看看那些因《兰亭序》而诞生的绘画和琳琅满目的器物。

《萧翼赚兰亭图》和《兰亭修禊图》

作为千古名作,《兰亭序》至唐代彰显于世以来为历代文人所推崇,取材于《兰亭序》相关故事、《兰亭序》序文、作者王羲之的典故及会稽兰亭胜景,皆可入画。从最早传为唐阎立本的《萧翼赚兰亭图》至明清时期各种《兰亭修禊图》《兰亭图》,与兰亭文化相关的绘画也有千年历史。

《萧翼赚兰亭图》历来传为出自初唐有“丹青神化”之誉的阎立本之手。画面描绘唐太宗御史萧翼从王羲之第七代传人僧智永的弟子辩才的手中将“天下第一行书”《兰亭序》骗取到手,并献给唐太宗的故事。唐人何延之写的《兰亭记》记载了这件逸闻。现存宋人摹《萧翼赚兰亭图》计有3本,北京故宫藏、辽宁省博物馆和台北故宫博物院各藏一卷,其中辽博和台北故宫藏本较为完整,北京故宫藏本相对较简略。研究者认为辽博、台北故宫藏本大致全是宋人临本,北京故宫藏本则是南宋人作品。辽博本和台湾故宫本构图基本相同,人物大小、用笔、设色上略有不同。

現藏辽宁省博物馆的《萧翼赚兰亭图》最近一次露面,是在该馆于2019年末至2020年初《又见大唐》展上()。该画纵26.5厘米,横75.7厘米,绢本设色,画面共有5人,萧翼、辩才和三个仆人。通过考察画面中仆人们的形象,研究者认为表现了萧翼和辩才初次见面的情景。

画的作者究竟是不是阎立本?现在存世的若干卷《萧翼赚兰亭图》相互关系如何?直到今天,这些问题始终没有解决,但传奇的故事和精湛的技艺都决定了它会成为千古名画,在宋及以后被反复临摹仿制。史载元代钱选、赵子俊以及明代仇英等多位后世知名画家皆绘过《萧翼赚兰亭图》。

除了萧翼赚兰亭的传奇故事外,历代画家们还经常以兰亭修禊场面为创作的题材。这个主题的绘画数量比《萧翼赚兰亭图》更多,元人赵孟頫、王蒙,明代文徵明、祝允明、唐寅、钱贡、许光祚,清人沈时、樊沂,再到当代傅抱石等都有与兰亭序相关的作品。此外,还有一些艺术水平很高的佚名作品。在此,我们仅举两例。

辽宁省博物馆藏有一卷传元代王蒙所绘制的《修禊图卷》。此卷绘画纸本水墨,纵28.8厘米,横135.5厘米,从款识看是元四家之一的王蒙所绘制,画后有唐寅书法《兰亭序》一通,书写时间为明正德十三年。虽然对这卷画真正的作者究竟是谁学者们有不同的意见,但哪怕作者不是王蒙,也一定是一个水平高超的画家。同时,这也不妨碍我们看图读画,遥想永和九年暮春的那场盛会。

明代祝允明书法造诣深厚,为明代吴中三大家之首。文徵明诗文书画无所不能,为吴门画派的领袖。他们也为兰亭合作了一把。这卷祝允明书《兰亭序》文徵明补图,一书一画,均属上乘之作,可谓珠联璧合。和上面那卷传为王蒙的《修禊图》相比,少了几分清逸,却多了一份暖融融的春日气息。

兰亭砚和鹅形砚

书画是古代文人的日课,兰亭的题材也深深地烙印在他们的案头。不同材料制作的各类文房器物上,随处可见兰亭的身影,时刻相伴左右。其中,最常见的是兰亭砚和鹅形砚。

以兰亭修禊情景或兰亭八景()作为砚台纹饰的砚称作“兰亭砚”。兰亭砚多为长方形或椭圆形,宽大厚重,六面分别雕刻王羲之等人兰亭禊饮盛况,北宋以后成为定型砚式,又因曲水流觞而称其为“曲水砚”。

目前存世宋代兰亭砚极稀少,多为明清时期制品。清代第一部官修砚谱——《西清砚谱》收录5方兰亭砚,其中最珍罕的当属宋米芾兰亭砚。端石制作,周壁上方及右侧刻有兰亭修禊图、米芾《兰亭序》全文和米芾的长方印。此外,还有表明它曾是南宋内府藏品的“宣和”及“绍”“兴”两字连珠印,砚背刻有乾隆御题诗。砚台略有残损,部分纹饰漫漶不清,但仍无法掩盖它上好的材质、精良的做工和在历代朝野间辗转的沧桑。

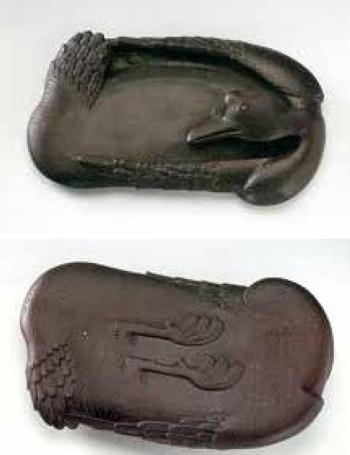

还有一种鹅形砚,也是源自兰亭风流的典范砚式。王羲之爱鹅,传说他曾手书一卷《黄庭经》和老道士换一笼鹅。羲之爱鹅被当作文人墨客文雅情趣的体现,后人将它和“陶渊明爱菊”“周茂叔爱莲”“林和靖爱鹤”并称“四爱”。古代制砚家状物模形,以鹅入砚,追慕书圣遗风。

鹅形砚一般以鹅肚为砚堂,鹅回首啄理羽毛,弯曲的鹅颈与鹅身之间形成砚池。在《西清砚谱》卷十七就有两方鹅形砚,我们且看其中之一。砚背伸出一双鹅掌,既是砚脚,又像白鹅拨动清波。盛水磨墨时,仿佛怀抱一汪清泉,意趣生动,观赏实用两不误。鹅形砚出现的具体时间尚待考证,但从当今博物馆藏有宋、元、明、清传世精品的情况来看,这种砚式历史悠久。

和鹅形砚相类似的,还有鹅纹砚。这类砚全器或方、或圆,或是随形,在砚面或砚背有一只或几只游鹅,或悠然自得,或追逐嬉戏,无不活泼可爱,妙趣横生。《西清砚谱》中多方砚上有“浴鹅图”。王羲之爱鹅的形象如此深入人心,兰亭鹅池的传说流传如此之广,以至于只需要在砚台上以鹅的形象稍作点缀,我们就知道这是向右军大人,向兰亭精神致敬。

高士杯和笔墨风流

明清以來,兰亭似乎成了清雅脱俗的代名词,流布于文房之外的各种器物上。

一件明成化斗彩高士杯,高仅3.4厘米,口径5.9厘米,足径2.7厘米。小小的个儿,哪怕放在女士手中也显得太小。薄薄的杯壁上,绘制两组斗彩纹饰:“王羲之爱鹅”和“俞伯牙携琴访友”,他们是古人高山仰止的高士,所以后人称这类杯子为“高士杯”。画面中王羲之着红衣,临池俯视水中游鹅,身后一绿衣童子手捧书卷,四周环以垂柳、野花,彩云轻飘。俞伯牙服绿衣,头扎双髻,稳步前行,一红衣书童抱琴相随,四周松柏苍翠,野菊丛簇。两组画面上的青花是釉下施彩,红彩和水绿则是釉上彩。这种釉下青花和釉上多种彩色相结合而成的新工艺,代表当时瓷器制作的最高水平,明代人用他们最高的工艺技术表达对书圣的仰慕。除了瓷器,明代人还把兰亭修禊刻到剔红漆器上,刻到犀牛角雕上,画到扇面里……

到了清代,兰亭成为最常见的装饰题材之一,尤其是文房用具和各类摆设,其中,品质最上乘、保存最完整的当属清宫旧藏。

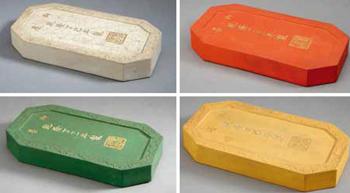

去故宫看看吧,清乾隆时期竹管兰亭赏狼毫笔,成组的清乾隆兰亭修禊御墨(),青田石兰亭序印章、乾隆款剔红曲水流觞图盒、青玉兰亭修禊图山子、白玉羲之爱鹅图勒子、乾隆款碧玉兰亭记双面插屏、青玉刻乾隆御笔兰亭玉如意……从实用的文房用器笔、墨、印章,到作为摆件的山子、插屏、玉如意,乾隆皇帝给自己配了全套兰亭定制用品。

一方墓志再续传奇

2006年,绍兴一位文物爱好者收藏的一方墓碑曾在文物圈和书法界引起小小的震动。这块墓碑长68.5厘米,宽56厘米,厚8.8厘米,隶书,共28行,345字。除部分字迹无法辨认外,绝大部分文字清晰可辨。乍一看,和同时期其他墓碑并无两样。内容显示,它的主人是王羲之夫人——郗璇。碑文记载了24个跟王羲之有密切关系的人,也为我们揭开了一段公案的谜底。

一代书圣王羲之生究竟哪年生?哪年死?关于王羲之的生卒年份,《辞海》出现过3个版本,分别为:“321~379”“303~361”“307~365”。虽然享年都是59岁,但生卒年不相同。没有文献记载,史家也无从定论。出土的墓碑记载,郗璇卒于升平二年即公元358年,时年王羲之56岁。王羲之比其夫人郗璇多活了3年,因此王羲之的卒年就是公元361年,卒年扣除享年,王羲之的生年即为公元303年,与《辞海》中3个版本中的一个相同。

随着王羲之夫人墓碑的出土,一段公案就此了结。可是,兰亭的传奇还在继续。从诞生到传家、从真迹到摹本、从书法到文化,《兰亭序》成为中国书法艺术的图腾,中国古代文化形态的标志。它产生、流传、消失、衍变和传播的历史,早已超越了王羲之为代表的魏晋文人风骨和精神世界,成为中国特有的一种艺术文化,并播及海外。修禊盛会、绝品墨迹、书圣风骨、兰亭胜迹,通过千年的物化和积淀,共同构筑了中国文化史上一个永不落幕的传奇。

Artworks Inspired byPreface to the Orchid Pavilion Collection

By Chen Yang

Wang Xizhi (303-361) is the saint of Chinese calligraphy. No other person in the history of China has this godly honor. His is considered a masterpiece in the style of semi-cursive script, aka script. The original was kept in the Wang clan for hundreds of years until the Tang Dynasty (618-907). After it came into the hands of the royal house of the Tang Dynasty, numerous copies were made by prominent calligraphers such as Feng Chengsu, Ouyang Xun, Yu Shinan and Zhu Suiliang. These handwritten copies gave rise to some carved replicas on stone tablets. History records that some collectors in the Song Dynasty (960-1279) had more than 100 different rubbings from stone tablets. Jia Sidao (1213-1275) who once served as prime minister of the Southern Song (1127-1279) had more than 800 different replicas in his collection of calligraphy. In the following dynasties, scholars and calligraphers were equally obsessed with the calligraphic masterwork.

Wang Xizhis preface inspired not only calligraphers of later generations, but also artists who painted Orchid Pavilion and related stories and figures for about 1,000 years. Yan Liben (c.600-673), a master painter of the early Tang Dynasty, created a painting illustrating how a guy named Xiao Yi outsmarted a disciple of a seventh-generation grandson of the Wang clan, put his hands on the manuscript, and presented it to the emperor. This anecdote is recorded in a book penned by a scholar of the Tang Dynasty. There are three different copies of the original painting by Yan Liben, now respectively in the possession of the Palace Museum of Beijing, Liaoning Provincial Museum and the Palace Museum of Taipei.

Wangs preface also inspired numerous artists to restore the scene of the spring-day outdoor party. The same story was painted again and again in the following dynasties and up to the 20th century. Artists who dedicated their time and talent to this subject include some greatest names in the history of Chinese art.

Wang Meng (1308-1385), one of the Big-Four artists of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), created an ink painting on a paper scroll which measures 28.8 centimeters tall and 135.5 centimeters wide. From the seals on the painting, the artwork can be ascribed to Wang Meng. Attached to the painting is a replica of the preface written in 1518 by Tang Yin (1470-1524) of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Some scholars argue the painting was not created by Wang Meng, but they all agree that it is a masterpiece. Another great artwork that portrays the gathering is a work jointly created by Zhu Yunming (1461-1527) and Wen Zhengming (1470-1559) of the Ming Dynasty. Zhu was an eminent calligrapher and Wen a versatile artist, both being among the best of their time. Zhu copied the preface and Wen created a painting to go with the calligraphy.

The Orchid Pavilion Ink-stone is a well-known stationery tool treasured by scholars of the past. The ink-stone named after Orchid Pavilion usually presents either a scene portrayed in the preface or eight scenes of the memorable place where the gathering took place. Such an ink stone first appeared in the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127). Most of them are lost in history. Some similar ink stones were made in the Ming and the Qing (1644-1911) dynasties. Another stereotypical ink-stone of the past is a goose-shaped design based on Wang Xizhis love of the bird. Such goose-shaped ink stones were made in the major dynasties from the Song on. These precious ink stones can be seen in various museum collections across China.

In the Ming the famous spring-time gathering first portrayed in the preface appeared in many artworks such as horn carvings, paper fans, porcelains as well as lacquer ware. In the Qing, the spring-time gathering was seen in most stationery pieces, as testified by the precious antiques in the collection of the Palace Museum in Beijing. Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799) loved the image and had a whole set of stationery and decorative pieces custom-made with this subject for his royal study.

In 2006, a tombstone in the possession of an antique collector in Shaoxing, Zhejiang caused a stir among calligraphers and antique experts and scholars. The stone bears a text of 345 words in 28 lines in the clerical script. Most of the words are legible. The text relates who was buried in the tomb and solved a problem that had puzzled historians for more than 1,000 years. Concerning the birth and death years of Wang Xizhi, (The Sea of Words), an authoritative dictionary, had offered three scenarios: 321-379, 303-361, 307-365 in different editions. The three different timelines suggested that Wang Xizhi died at the age of 59, but historians had no way to find out exactly when he was born or died. The tombstone clarifies: Wangs wife Xi Xuan died in 358 when Wang Xizhi was 56. If the theory that Wang Xizhi died at 59 is correct, then it was 361 when he passed away and therefore he was born in 303.