Nonasthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis in an ulcerative colitis patient- a putative adverse reaction to mesalazine:A case report and review of literature

2020-04-08AndreiTudorCernomazGabrielaBordeianuCristinaTerinteCristinaMariaGavrilescu

Andrei Tudor Cernomaz,Gabriela Bordeianu,Cristina Terinte,Cristina Maria Gavrilescu

Andrei Tudor Cernomaz,Cristina Maria Gavrilescu,Department of Internal Medicine,Grigore T.Popa University of Medicine and Pharmacy,Iasi 700115,Romania

Gabriela Bordeianu,Department of Biochemistry,Grigore T.Popa University of Medicine and Pharmacy,Iasi 700115,Romania

Cristina Terinte,Department of Pathology,Regional Oncology Institute,Iasi 700483,Romania

Abstract BACKGROUND Lung and airway involvement in inflammatory bowel disease are increasingly frequently reported either as an extraintestinal manifestation or as an adverse effect of therapy.CASE SUMMARY We report a case of a patient with ulcerative colitis controlled under mesalazine treatment who presented with chronic cough and hemoptysis.Chest computed tomography and bronchoscopy findings supported tracheal involvement in ulcerative colitis;pathology examination demonstrated an unusual eosinophilrich inflammatory pattern,and together with clinical data,a nonasthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis diagnosis was formulated.Full recovery was observed within days of mesalazine discontinuation.CONCLUSION Mesalazine-induced eosinophilic respiratory disorders have been previously reported,generally involving the lung parenchyma.To the best of our knowledge,this is the first report of mesalamine-induced eosinophilic involvement in the upper airway.

Key Words:Mesalamine;Ulcerative colitis;Hemoptysis;Bronchitis;Drug-related side effects;Case report

lNTRODUCTlON

Mesalazine is a 5-aminosalicylic acid derivative recommended for the long-term management of mild and moderate forms of inflammatory bowel disease.The adequate efficacy and safety profile of this drug explain its frequent use[1].

Mesalazine respiratory toxicity is uncommon and incompletely understood.Relevant available data consist mainly of case reports concerning mesalazine-induced eosinophilic pneumonia,nonspecific interstitial pneumonia(NSIP)and cryptogenic organizing pneumonia(COP)[2].

We report the case of an ulcerative colitis(UC)patient who developed chronic nonspecific respiratory symptoms with mesalazine treatment;available data support the idea of a previously unreported respiratory side effect.

CASE PRESENTATlON

Chief complaints

A 40-year-old woman was referred to our tertiary level pneumology unit for an irritating chronic cough sometimes accompanied by mild hemoptysis(up to 20 mL fresh blood/d).

History of present illness

These symptoms had been present for the last six months;no clear triggers or aggravating factors were identified.

History of past illness

She was a nonsmoker,had no previous pulmonary diseases and had no significant occupational exposure.The patient had a six-year history of moderate UC managed mainly by dietary advice and cycles of mesalazine.

Six months prior to admission in our hospital,she had been evaluated for digestive complaints:Cramping periumbilical pain,loose bowel movements and rectorhagia;colonoscopy was performed,and pathological data confirmed an UC flare up that prompted mesalazine treatment(Eudragit coated tablets 6 g daily,same formula that the patient previously used).The digestive complaints subsided,but respiratory symptoms(dry cough that aggravated during the night,sometimes with mild hemoptysis)seemed to develop two weeks following admission to the gastroenterology department.An infectious etiology was presumed by her general practitioner,although the chest radiographs and sputum cultures were negative;symptomatology persisted under two courses of broad spectrum antibiotics(amoxicillin/clavulanate 2 g daily,10 d,clarithromycin 500 mg daily,7 d).After approximately one month the patient was referred to a secondary pneumology unitatopic reaction(to an unidentified agent)and cough variant asthma were considered and patient received antihistamine(levocetirizine 5 mg daily,14 d)and inhaled beta 2 mimetic and corticoid treatment(beclometasone/formoterol 100/6 μg every 12 h,ongoing).As no significant clinical improvement was noted after three months,the patient was referred to our tertiary pneumology unit for further evaluation.

Physical examination

Physical examination was unremarkable.Lung function tests were within the normal range.

Laboratory examinations

The patient had mild eosinophilia(780 elements/mmc,10.3%);no other significant hematological or biochemical anomalies were found.

Imaging examinations

Computed tomography of the chest demonstrated irregular circumferential thickening of the subglottic region and upper trachea,a diffusely enlarged thyroid and sparse tracheal nodules(Figure 1);the distal airways,lung parenchyma and mediastinal structures were normal.

Pathologic evaluation

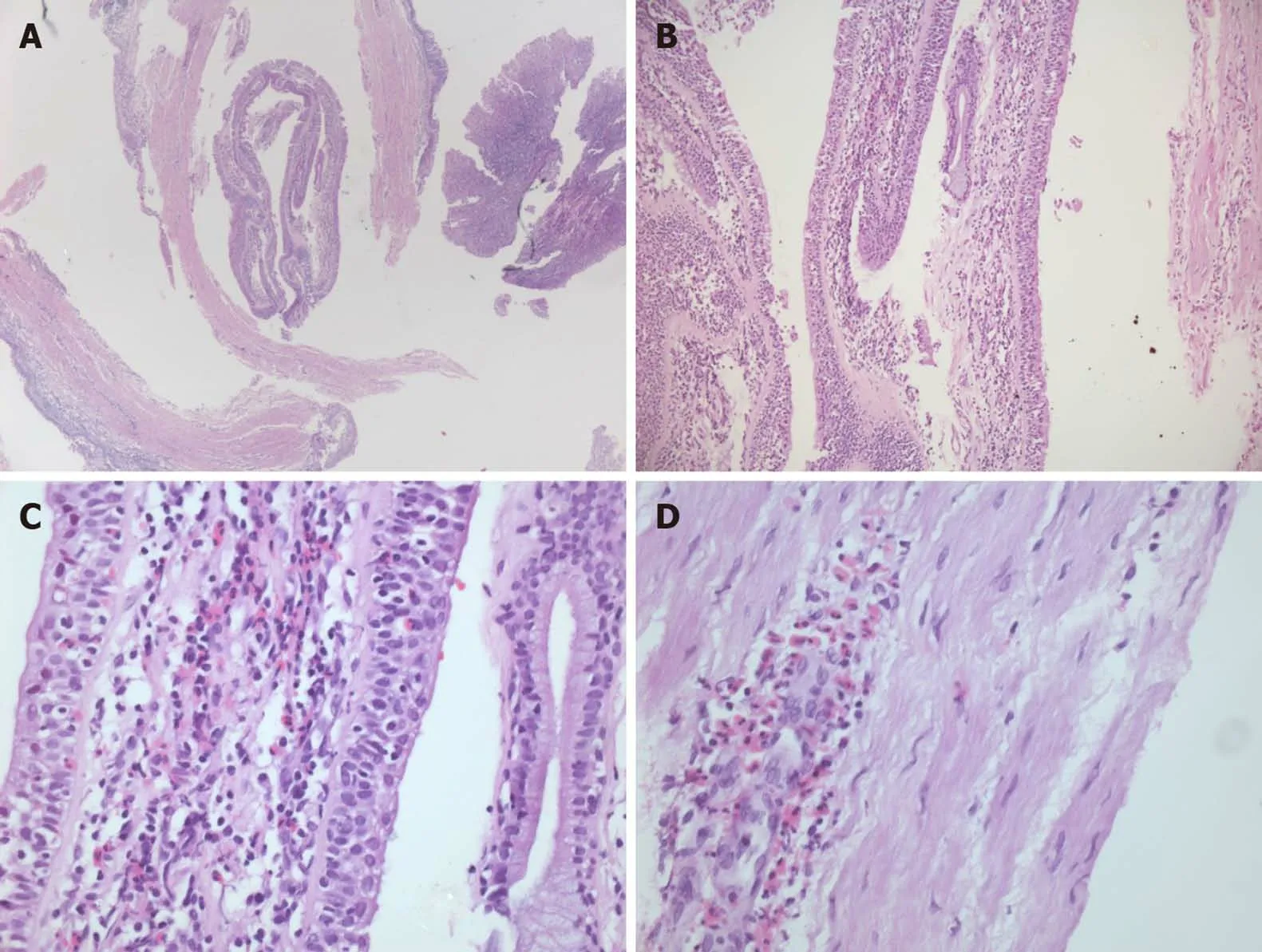

Flexible bronchoscopy showed viscous tracheal secretions and edematous,friable,nodular mucosa from the larynx to main bronchi;no clear hemorrhagic spots were identified;serial biopsies were performed(tracheal,carina and main bronchi).Bronchial fluid bacteriology tests were negative;cytology showed a neutrophilic/eosinophilic inflammatory profile.The biopsy specimens showed deep mucosal ulcerations with granulation tissue,abundant inflammatory infiltrate containing numerous eosinophils,epithelial healing with squamous metaplasia and regenerative atypia(Figure 2).

FlNAL DlAGNOSlS

Available clinical and pathology data were compatible with mesalazine-triggered nonasthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis(NAEB).

TREATMENT

We opted for mesalazine discontinuation and continued inhaled corticoids/longacting beta mimetics(beclometasone/formoterol 100/6 μg every 12 h).

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Cough and hemoptysis subsided after one week following mesalazine discontinuation.Inhaled beclometasone/formoterol was stopped after one month and patient was discharged to gastroenterology services for UC management with a mesalazine avoidance recommendation.Patient remained symptom free at the six-month follow up being managed only on dietary advice.

DlSCUSSlON

Respiratory manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease are well recognized;the incidence is considered to be low,although underdiagnosis may be a problem[3,4].

Both the airways and lung parenchyma may be involved;chronic bronchitis,bronchiectasis,and COP are typical associations[5-7],tracheal and large airway involvement is rarely mentioned.As available data are limited to case reports,less than 50 total to the best of our knowledge,it is difficult to compile a clear archetypal picture of upper airway involvement in UC;nevertheless,some common elements have emerged from the available literature[8].Tracheal lesions seem to affect mainly nonsmoking young females with UC during a stable phase of the disease(even after colectomy)[9].The symptoms/signs are nonspecific and of variable intensity,including hoarseness,chronic cough,sputum production,and in severe cases,upper airway obstructive syndrome[10].Bronchoscopy demonstrated various patterns:Erythema,edema,attenuation or disappearance of the stripes of the tracheal cartilage,and whitish granular lesions,mucosal folds and nodules,which were sometimes described as papillomatous.

Figure 2 Hematoxylin-eosin stained tracheal mucosal biopsies demonstrating the presence of eosinophil-rich infiltrate.A:Magnification 25×;B:Magnification 100 ×;C:Magnification 200 ×;D:Magnification 400 ×.

Pathology shows nonspecific findings(some findings may coexist)[11]:Inflammatory infiltrate dominated by lymphocytes or neutrophils[12],some authors specifically noted the relative absence of eosinophils[13];squamous metaplasia;ulceration;and granulation tissue with fibrin rich exudate and re-epithelialization[14];granuloma formation is possible[15],thus prompting the differential diagnosis with sarcoidosis,tuberculosis,amyloidosis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis.Corticoids,either inhaled[16]or systemic,and other immunomodulator agents are considered effective,but scarring and severe tracheal stenosis may develop[14,17].

Our case shares some features with the reported cases of UC with tracheal involvement but differs from the pathological point of view because of the presence of the eosinophil-rich infiltrate.

This prompted us to formulate three hypotheses:A rare,previously undescribed inflammatory pattern of the upper airway in UC,mesalamine adverse effects,or other causes of eosinophilic tracheo-bronchitis.Clinical data seemed to support the mesalamine hypothesis - the symptoms appeared shortly after treatment initiation and promptly disappeared following drug cessation.

To assess causality,both the Naranjo algorithm and World Health Organization-Uppsala Monitoring Center(WHO-UMC)criteria were applied using available data.The Naranjo algorithm returned a score of 6,corresponding to a probable adverse drug reaction,especially considering the following:Symptoms onset after the suspected drug was given,improvement after drug discontinuation,no credible alternative causes,and confirmed by objective evidence.

Similarly,using the WHO-UMC causality assessment scale,we considered an adverse drug reaction as probable or likely,as the clinical and pathological findings seemed to have a reasonable relationship with drug intake,no other explanations were found,and the response to withdrawal was clear.

A drug rechallenge would have provided valuable data but was deemed unethical as long as the patient was symptom free and alternative medication was available for the pharmacological management of UC in case of a flare up.

Mesalazine is currently considered a first-choice drug for mild and moderate UC[1];its use is rarely associated with respiratory adverse reactions,with the notable exception of rhinitis/pharyngitis,which is considered common.Mesalazine allergic reactions and eosinophil-related disorders,such as eosinophilic pneumonia,have been described but are considered extremely rare[18,19].Furthermore,according to the available sparse data,available mesalamine respiratory adverse events typically involve the lung parenchyma and distal airways[2];COP[20],NSIP,and eosinophilic alveolitis[19,21]have been reported,with potential serious consequences[22],while the large airways seem to be spared.Drug discontinuation,corticoids and other immune modulators have been reported as generally effective approaches in such cases[18,23,24].

Mesalazine respiratory toxicity is not completely understood,and various mechanisms have been postulated,including both immune(dose independent)and direct(dose dependent)mechanisms[25-27].There are data suggesting that various formulations of mesalazine have different safety profiles[28];while the excipients used may play a role,an alternative explanation may rest on pharmacodynamic differences between formulations[29].We did not consider excipients or pharmacodynamic differences to be relevant for our patient,as she previously used the same mesalazine formulation from the same producer;furthermore,the six-month treatment duration makes a manufacturing issue extremely improbable.

It is also worth mentioning that mesalazine adverse reactions may develop after variable exposure periods ranging from a few days to more than five years[30,31].

An attempt to systematize the clinical manifestations was made:The presence of chronic cough for more than 8 wk,normal lung function tests,lack of response to bronchodilators,eosinophil-rich bronchial aspirate and eosinophilic infiltration of the tracheal and bronchial mucosa were compatible with a positive diagnosis of either NAEB or atopic cough[32-34].The lack of response to corticoids and antihistaminic agents tips the balance towards a NAEB diagnosis - mesalazine discontinuation and the use of low-dose inhaled corticoids were in accordance with relevant clinical practice guidelines[35].

NAEB is usually linked to exogenic exposure,and multiple culprits have been reported:Isocyanates,acrylates,welding fumes,resin hardeners,formaldehyde,latex,and flour[36,37].The pathogenesis of NAEB,while not completely understood,shares mechanisms with asthma[33],one notable difference is the increased prostaglandin D2 concentration in the sputum of NAEB patients[38].Prostaglandin D2 is involved in UC healing processes,and its synthesis in the colonic mucosa is upregulated during longterm remission[39].The biological effects of PD2 are mediated by its receptors:D-type prostanoid,which has an anti-inflammatory role;and CRTH2,which has a proinflammatory role and is known to be involved in eosinophilic activation(and actually used as a therapeutic target in asthma)[40].

Considering this,we might infer that in our case,NAEB was the consequence of extraintestinal UC involvement,with tracheal inflammation being modulated by mesalazine towards an eosinophilic pattern.Such a hypothesis might explain both the tracheal localization and evolution on drug discontinuation,but the limited available data do not allow for further substantiation.

CONCLUSlON

To the best of our knowledge,this is the first report of nonasthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis as a probable type B adverse reaction to mesalazine in a UC patient.

Both respiratory involvement in inflammatory bowel disease and mesalazine adverse effects,while infrequent,may significantly alter quality of life and lead to serious and potentially lethal complications;UC patients with chronic respiratory symptoms should be thoroughly investigated,and the data should be carefully considered.

Physicians confronted with such a case are recommended to perform invasive approaches as pathology data may prove useful in guiding management even in the absence of a clear-cut diagnosis.

杂志排行

World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Special features of SARS-CoV-2 in daily practice

- Gastrointestinal insights during the COVID-19 epidemic

- From infections to autoimmunity:Diagnostic challenges in common variable immunodeficiency

- One disease,many faces-typical and atypical presentations of SARS-CoV-2 infection-related COVID-19 disease

- Application of artificial neural networks in detection and diagnosis of gastrointestinal and liver tumors

- Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma:Update on diagnosis and therapy