Acute leukemic phase of anaplastic lymphoma kinase-anaplastic large cell lymphoma: A case report and review of the literature

2020-04-07HuaiFengZhangYanGuo

Huai-Feng Zhang, Yan Guo

Huai-Feng Zhang, Yan Guo, Department of Hematology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Shandong First Medical University, Jinan 250014, Shandong Province, China

Abstract BACKGROUND Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a rare and heterogeneous malignant tumor, which is classified as anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)positive ALCL and ALK- ALCL. Many patients are diagnosed with ALCL at the stage of bone marrow involvement. However, ALCL patients with clinical manifestations consistent with acute leukemia are relatively rare.CASE SUMMARY In this report, the patient did not receive appropriate diagnosis and treatment despite a two-year history of lymph node enlargement. Hereafter, she was admitted for B symptoms and was diagnosed as ALK-ALCL by lymph node biopsy. Then, the disease progressed to leukemia without any treatment after 2 mo. The proportion of lymphoma cells in bone marrow was as high as 96%, and the proportion of peripheral blood was 84%. She also had clinical manifestations similar to acute leukemia. After completion of chemotherapy, she developed granulocytopenia and fever and died from septicemia.CONCLUSION ALCL with leukemic presentation is a late manifestation of lymphoma with low chemotherapy tolerance and poor prognosis.

Key Words: Anaplastic large cell lymphoma; Anaplastic lymphoma kinase; Prognosis;Leukemic phase; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a relatively rare heterogeneous malignancy.According to the World Health Organization 2008 Classification for ALCL, the systematic ALCL is classified as anaplastic lymphoma kinase positive (ALK+) ALCL and anaplastic lymphoma kinase negative (ALK-) ALCL based on expression of ALK[1]. Previously, ALK- ALCL was considered as a provisional entity. In 2016, ALKALCL was first recognized as a definite entity characterized by high CD30 (Ki-1)expression, large cell proliferation and no ALK protein expression[2]. ALK- ALCL,which accounts for 2%-3% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and 12% of T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases, can occur in all age groups with a peak at 40 to 65 years old, and it is more common in males[1]. The ALK- ALCL has a worse prognosis than ALK+ ALCL though their morphology is considered to be similar.

ALK- ALCL may be presented as various clinical manifestations. Besides peripheral and/or abdominal lymphadenopathy, patients with ALK- ALCL often have aggressive clinical symptoms, including B symptoms, elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels and high International Prognostic Index score[3]. Unlike the ALK+ ALCL, ALK- ALCL involves less extranodal tissues[4]. Most patients are diagnosed with ALCL at the stage of bone marrow involvement. However, ALCL patients with clinical manifestations consistent with acute leukemia are relatively rare.Herein, we reported a case of untreated ALK-ALCL that rapidly progressed to acute leukemia and performed a literature review.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 49-year-old female presented with bilateral submental and inguinal lymphadenopathy without pain or other discomfort.

History of present illness

The patient was admitted two years ago presenting with bilateral submental and inguinal lymphadenopathy without pain or other discomfort. Thereafter, the size of the involved lymph nodes was progressively growing and presented as redness in appearance. Meanwhile, she had fatigue and fever.

History of past illness

None.

Personal and family history

No personal and family history available.

Physical examination

Swollen lymph nodes in the bilateral armpits, bilateral neck, supraclavicular, and groin area.

Laboratory examinations

The serum LDH level was 554.00 U/L. Peripheral blood routine results: White blood cell, 3.02 × 109/L; lymphocytes, 0.16 × 109/L; hemoglobin, 132 g/L; and platelet count,135 × 109/L.

Imaging examinations

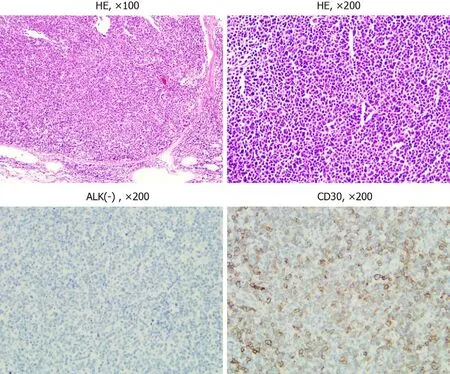

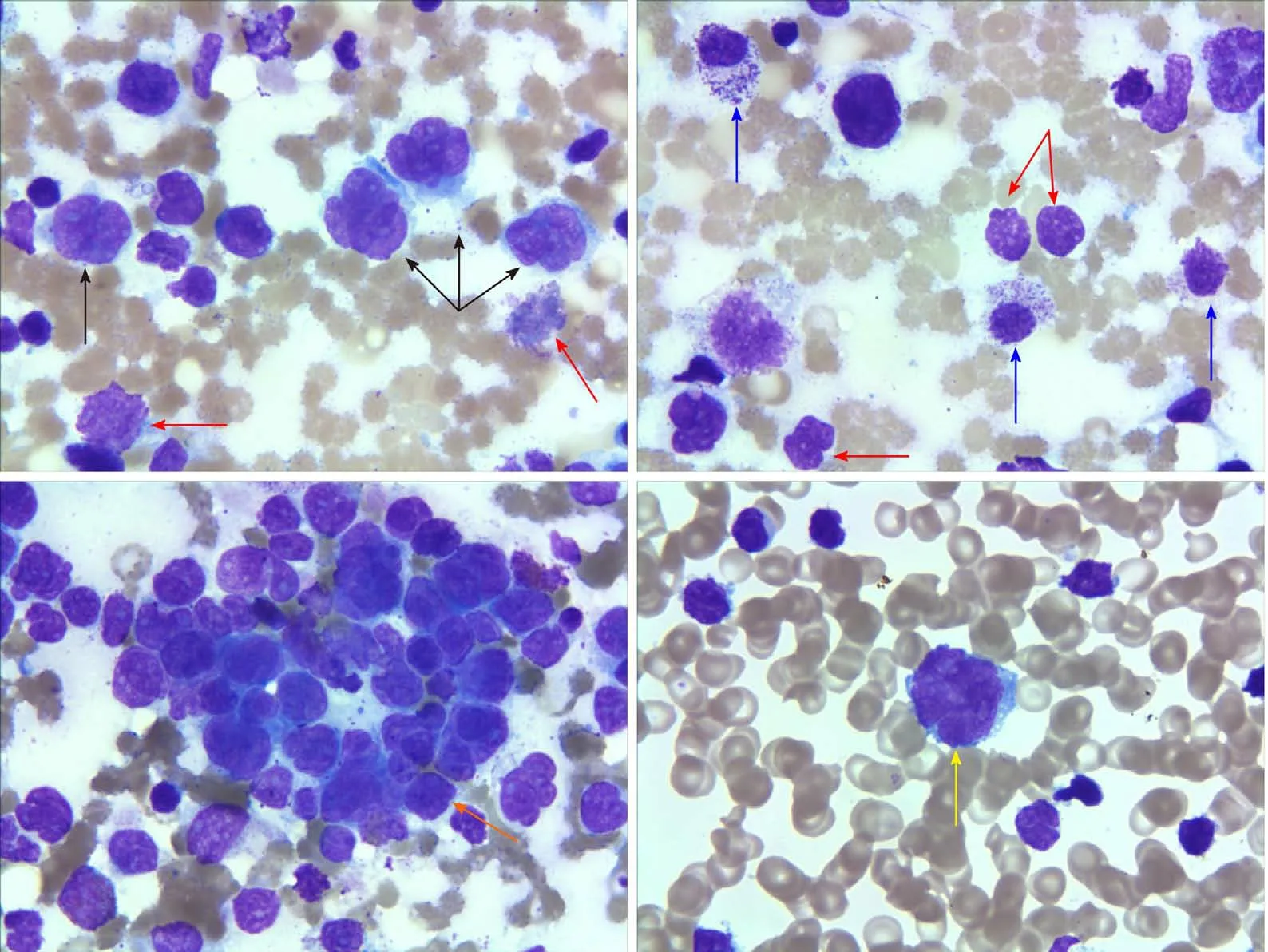

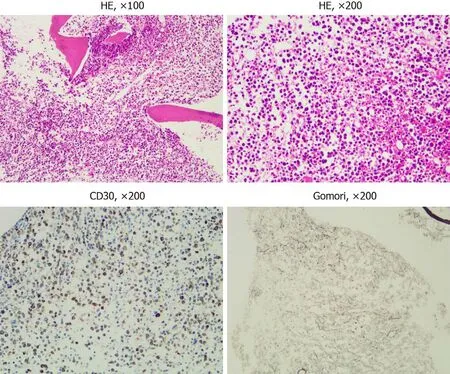

Chest and abdomen computed tomography scans showed splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy in hilum of the right lung, mediastinum and bilateral axilla,abdominal cavity, and retroperitoneum. Immunohistochemistry of left axillary lymph node biopsy showed anaplastic large cell lymphoma with CD30 (+), ALK (-), CD3(part +), CD5 (part +), CD7 (individual +), EBER (-), CD20 (-), CD10 (-), Bcl-2 (-), Bcl-6(-), Mum-1 (individual +), C-myc (-), and Ki-67 (70%) (Figure 1). She refused to receive bone marrow biopsy and chemotherapy and was discharged. After 2 mo, she was readmitted, with presentations of fatigue, poor appetite, and fever. Laboratory tests:White blood cell, 92.55 × 109/L; lymphocytes, 24.99 × 109/L; hemoglobin, 93.0 g/L;Platelet count, 33 × 109/L; lactate dehydrogenase, 4968.00 U/L; and Serum sodium 112.0 mmol/L. The results of a bone marrow smear (Figure 2) showed 96% medium to large lymphoma cells with convoluted nuclei and small nucleoli. In peripheral blood smears, lymphoma cells accounted for 84%. Bone marrow biopsy showed that there were many CD30 (+) tumor cells among the trabecular bones (Figure 3) and ALK (-),EBER (-), and lack of B lymphocyte immunolabeling. Reticular fiber staining was 2+ -3+.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Combined with all the above examinations, the patient was clearly diagnosed as ALK(-) ALCL, leukemic phase.

TREATMENT

The patient was given chemotherapy with DA-EPOCH regimen.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

At 4 d after chemotherapy, she developed granulocytopenia and fever. Blood culture showedKlebsiella pneumoniae. Although given antibiotics, unfortunately, septic shock and death occurred in the short term.

DISCUSSION

ALCL is an aggressive CD30+ T-lymphocyte proliferative disease. Steinet al[5]first identified ALCL. Morriset al[6]studied the gene pathogenesis of ALCL and found the recurrent t(2;5)(p23;q35) translocation, which led to the fusion ofALKgene and the nucleophosmin gene. The diagnosis of ALCL is mainly dependent on the morphology and immunohistochemistry results of a lymph node biopsy. In the World Health Organization 2008 Classification, while ALK+ ALCL was recognized as a definite entity, systemic ALK- ALCL remained as a provisional entity due to lack of definite criteria to distinguish it from other CD30+ peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs)[1].Previous studies have shown that the clinical manifestation, efficacy, and prognosis of ALK- ALCL were significantly different from those of ALK+ ALCL and peripheral Tcell lymphomas[7,8]. In the World Health Organization 2016 Classification, ALK- ALCL was recognized as a definite entity[2].

Figure 1 Hematoxylin and eosin staining and immunohistochemical staining results. The lymphoma cells showed pleomorphic large cell proliferation gathering in the lymph node sinus under hematoxylin and eosin staining at low magnification (× 100). At high magnification (× 200), the cells were gray blue, rich in cytoplasm, pleomorphic nuclei, and obvious nucleoli. HE: Hematoxylin and eosin; ALK: Anaplastic lymphoma kinase.

Figure 2 Bone marrow and peripheral blood smear results.In a bone marrow smear, the size of the lymphoma cells varied (black arrows). The cells aggregated and inlaid with each other (orange arrow). Damaged cells with varied size were observed (red arrows). The structures of some granulocytes were unclear(blue arrows). In peripheral blood smears, lymphoma cells accounted for 84% (yellow arrow) (Wright-Giemsa, × 1000).

ALK- ALCL is often accompanied by systemic disseminated lesions and presented as B symptoms. The lesions may occur within lymph nodes or in extranodal organs including bone, soft tissue, or skin. Most patients with ALK- ALCL are diagnosed at clinical stage III or IV due to atypical and uncommon acute leukemic presentations[3].ALK- ALCL is common in middle-aged and elderly males, while ALK+ ALCL is more common in young people less than 30 years old or children. Except for ALK, the morphology and immunohistochemistry of ALK- ALCL are similar to ALK+ ALCL.However, ALK- ALCL shows a different prognosis according to different gene rearrangements, which can be divided into DUSP22 (6p25.3), TP63 (3q28)rearrangement, or all-negative patients. The five-year overall survival rate in DUSP22 rearrangement patients can reach 90%, while is 17% in TP63 rearrangement patients[9].The average overall survival rate is 40%-60% in ALK- ALCL patients, which is much lower than that in ALK+ ALCL[9].

For ALK+ ALCL patients, the bone, subcutaneous tissue, and spleen involvement are common. However, ALK- ALCL mainly involves the skin, liver, and gastrointestinal tract[7]. Villamoret al[10]first reported that patients with a small-cell variant of ALCL with T-cell phenotype and ALK-1 positive developed a rapid leukemic phase. A previous study[11]has shown that ALK+ ALCL patients may have presentations of leukemia at any stage of ALCL development. Leukemia phase in ALK+ ALCL is usually associated with small-cell variant and t(2;5) (p23;q35)translocation, which is more common in stage III or IV patients, indicting a poor prognosis[12-18]. Furthermore, ALK+ ALCL patients with presentations of leukemia always have complex secondary chromosome abnormalities including 1q21, 10q24, t(3;8)(q26.2; q24) and overexpression ofMCL1,HOX11/TCL3, orC-myc, which were also associated with a poor prognosis[19-21].

However, leukemia phase was uncommon in patients with ALK- ALCL[3]. In 2005,Dalalet al[22]reported a case of ALK- ALCL with leukemia presentations. This case had 12%-20% irregularly shaped blast-like cells in peripheral blood film and had no evidence of the t(2;5) translocation but a complex karyotypic abnormality with involvement of chromosomes 1, 2, 5, 7, 8, and 15[22]. Wonget al[23]also reported a ALKALCL case with complex karyotypes that had leukemia phase. Leukemia phase is relatively rare in ALK- ALCL, although bone marrow involvement is common.Therefore, there are few case reports concerning ALK- ALCL with leukemia phase.

Whether the difference in terms of prognosis between ALK- and ALK+ ALCL patients is related to the presence of the ALK fusion protein has been controversial. In addition to age < 40 years, β-2 microglobulin is a prognostic factor for overall survival of ALK+ ALCL and ALK- ALCL[24]. Liver involvement, albumin levels, and International Prognostic Index are prognostic factors for ALK- ALCL. Regardless of ALK expression, bone marrow infiltration appears to be associated with poor prognosis in ALCL[25]. In our report, the patient had enlarged lymph nodes for two years but did not receive systematic diagnosis and treatment. Unfortunately, bone marrow aspiration was not performed at the first admission. Thus, we cannot clarify the exact time of bone marrow involvement. The pathological results of the lymph nodes was EBER (-), and no other B cells were observed. There was currently no evidence that the leukemia was transformed from B-cell lymphoma. The patient was then diagnosed as ALK- ALCL by lymph node biopsy and rapidly progressed to lymphoma leukemia after 2 mo of noncompliance to treatments. The proportion of lymphoma cells in bone marrow reached 96%, which may mistakenly indicate an acute leukemia. After progressing to lymphoma leukemia, she died in the short term. It is a limitation that we did not perform a chromosome test for this patient during disease progression.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, ALCL with leukemic presentation is a late manifestation of lymphoma with low chemotherapy tolerance and poor prognosis. We thought that untreated interstitial large cell lymphoma would eventually progress to the leukemia phase. Risk factors associated with leukemia transformation and post-transformation treatment strategies deserve further investigation.

Figure 3 Hematoxylin and eosin staining, immunohistochemical staining, and Gomori staining results. Bone marrow biopsy showed bone marrow hyperplasia and morphology similar to lymph node biopsy. There was diffuse positive CD30 expression. Gomori staining showed reticular fiber hyperplasia.

杂志排行

World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Strategies and challenges in the treatment of chronic venous leg ulcers

- Peripheral nerve tumors of the hand: Clinical features, diagnosis,and treatment

- Treatment strategies for gastric cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Oncological impact of different distal ureter managements during radical nephroureterectomy for primary upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma

- Clinical characteristics and survival of patients with normal-sized ovarian carcinoma syndrome: Retrospective analysis of a single institution 10-year experiment

- Assessment of load-sharing thoracolumbar injury: A modified scoring system