Global whole family based-Helicobacter pylori eradication strategy to prevent its related diseases and gastric cancer

2020-03-23SongZeDing

Song-Ze Ding

Abstract Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infects approximately 50% of the world population.The multiple gastrointestinal and extra-gastrointestinal diseases caused by H.pylori infection pose a major healthcare threat to families and societies; it is also a heavy economic and healthcare burden for countries that having high infection rates. Eradication of H. pylori is recommended for all infected individuals.Traditionally, “test and treat” and "screen and treat" strategies are available for various infected populations. However, clinical practice has noticed that these strategies have some shortfalls and may need refinement, mostly due to the fact that they are not easily manageable, and are affected by patient compliance,selection of treatment population and cost-benefit estimations. Furthermore, it is difficult to control infections from the source, therefore, development of additional, compensative strategies are encouraged to solve the above problems and facilitate bacteria eradication. H. pylori infection is a family-based disease, but few studies have been performed in a whole family-based approach to curb its intra-familial transmission and the development of related diseases. In this work,a third, novel whole family-based H. pylori eradication strategy is introduced.This approach screens, identifies, treats and follows up on all H. pylori-infected individuals in entire families to control H. pylori infection among family members, and reduce its long-term complications. This strategy is high-risk population-oriented, and able to reduce H. pylori spread among family members.It also has good patient-family compliance and, importantly, is practical for both high and low H. pylori-infected communities. Future efforts in these areas will be critical to initiate and establish healthcare policies and management strategies to reduce H. pylori-induced disease burden for society.

Key words: Helicobacter pylori; Intra-familial infection; Gastrointestinal disease; Gastric cancer

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori(H. pylori) infection, the major cause of chronic gastritis, peptic ulcers and gastric cancer, infects approximately 50% of the world population, is also closely associated with many extra-gastrointestinal diseases. These include idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, iron deficiency anemia, vitamin B12 deficiency,autoimmunity diseases, heart and cerebrovascular diseases,etc[1,2]. The latest cancer statistics in 2018 noted that gastric cancer is the fifth most frequently diagnosed cancer and third leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide[3].H. pylorieradication has been set as a strategy for preventing gastric cancer by IARC/WHO in 2014[4]. Populationbased observation, systematic review and meta-analyses have demonstrated thatH.pylorieradication can lead to reduction in the incidence of gastric-related disease and cancer, depending on the severity and extent of damage at the time of eradication[5-8].

Although there are huge number of people infected, and international consensus reports have clearly indicated its urgency[1,2,9,10], due to the slowly progressing nature ofH. pyloriinfection that does not result in immediately losing labor or disturbing society’s stability, the prevention and eradication ofH. pyloriinfection in most countries has yet to receive attention to the extent of other common infectious diseases, including tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus,and hepatitis C virus infection. The financial and healthcare burden could be fairly heavy if all the costs ofH. pylori-related treatments and hospital expenses are added up. Approximately 30% of infected persons will develop various kinds of diseases,such as dyspepsia, gastritis, peptic ulcers, atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia,gastric malignancies and multiple extra-gastrointestinal diseases[10]. Therefore,developing novel healthcare policies or management strategies for prevention,treatment, education and improving public awareness of its hazardous effects will be critical for reducingH. pylori-related disease burden for the society.

WHOLE FAMILY H. PYLORI INFECTION, INTRA-FAMILIAL TRANSMISSION AND DISEASE PROGRESSION

The Kyoto global consensus report onH. pylorigastritis in 2015 indicated thatH. pylorigastritis is an infectious disease. All infected persons will have different degrees of gastritis, and eradication ofH. pyloriremoves the reservoir of infection, reduces the incidence of infection, and prevents severe complications[2]. Other guidelines including management ofH. pyloriinfection, the 2017 Maastricht V/Florence Consensus report, and guidelines from the United States, China, Japan, and Asiapacific, as well as several large clinical observations, have also proposed that eradication ofH. pyloribefore gastric mucosal atrophy and intestinal metaplasia can reduce the risk of gastric cancer. Furthermore, they recommended treatment of allH.pylori-infected patients[1,5-12]. We have further proposed a strategy in China to “screen,identify, treat and follow up on allH. pylori-infected individuals in the entire family”.This is to preventH. pylorispreading among family members in order to reduce infection and its long-term complications, as infected family members are always a risk source for transmission[13](Table 1).

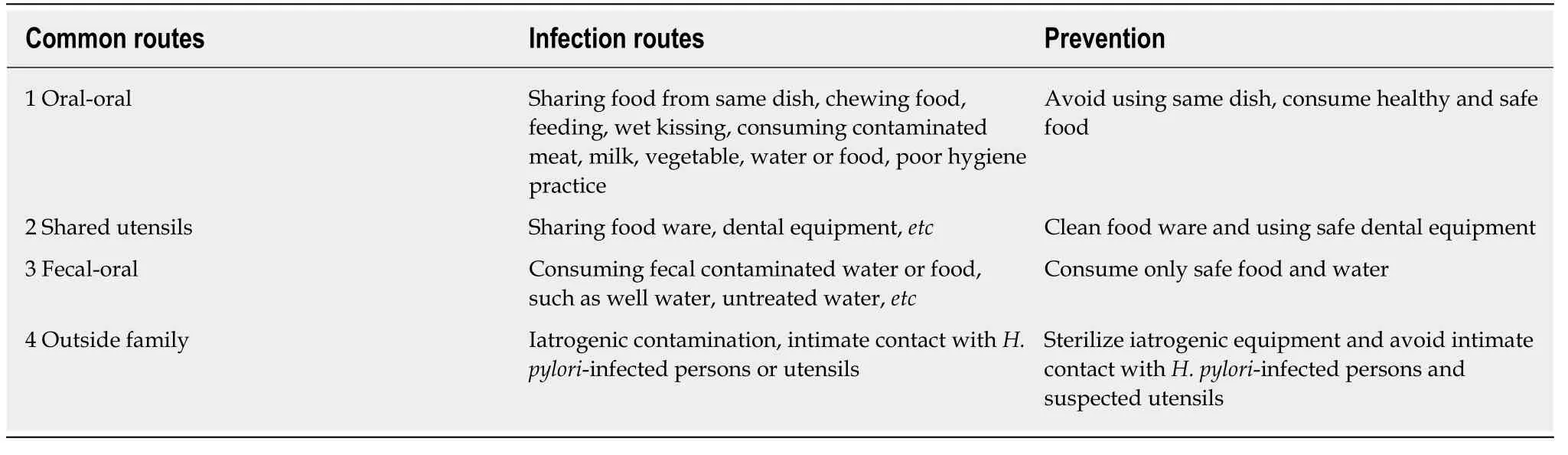

Increasing evidence has demonstrated thatH. pylorican be found in various environments, including water and food products for the family[14-19].H. pyloriis primarily transmitted by oral-oral and fecal-oral routes. Intra-familial spreading is a major form ofH. pyloriinfection[12,20]; the bacterium has been cultivated from vomitus,saliva and cathartic stool from infected persons, and was detected in dental plaques and cavities[1,21]. Furthermore, the bacterium can survive in milk, ready-to-eat foods,vegetables, juices, and meats for certain periods of time. It was also detected in various family food products such as water, vegetables, and different sources of meat as reviewed by Quaglia and Dambrosio[14].H. pyloriwas also detected and isolated from animal gastric mucosa such as sheep and cows[15,16]. Its presence in drinking water, freshwater, well water, estuarine, seawater and marine products were reported by using either molecular methods or bacteriological culture[14,17-19]. Despite further confirmation are required, this information clearly suggests that these are all potential sources of infection and are possible transmission routes for a family (Table 2).H.pyloriinfection is therefore speculated to be a foodborne or waterborne disease, with humans and animals as the likely reservoir[14].

Table 1 Traditional and suggested Helicobacter pylori infection management strategies1

Studies have shown that mostH. pyloriinfections occur in childhood, and are less common in adulthood; intra-familial transmission is the major path forH. pyloriinfection for children, mainly spread by parents, especially mothers[12,20,22]. The common routes of infection among family members include sharing food from the same dish, food ware, dental equipment, chewing food feeding, kissing, poor hygiene practiceetc. After infection early in life, the chronic gastritis slowly progress for years following Correa cascade, namely chronic gastritis, atrophy, intestinal metaplasia,intraepithelial neoplasia, and gastric cancer. This in turn results in the above disease presentations at adulthood[1,2]. In addition, various factors affect intra-familial transmission such as religion, location, ethnicity, living habits, social-economic status,and family size[2,9,10]. Infection tends to begin before the age of 12, and the Kyoto consensus report statements 16 and 17 therefore recommend that screening and treatingH. pyloriinfection be initiated after 12 years of age in variousH. pyloriinfected areas to prevent subsequent atrophy and intestinal metaplasia[2]. In recent years, Japan and South Korea have begun a nation-wideH. pylorieradication program to reduce the incidence of gastric cancer and related diseases, therefore saving on future medical expenses[23,24].

Multiple surveys have confirmed that the prevalence ofH. pyloriinfection in childhood steadily increases with age, but with variations that depend on geographic areas and countries[12,25,26]. A recent survey of 1,634 endoscopy-examined pediatric patients in Shanghai, China revealed that in children less than 3 years, 4-6 years, 7-10 years, and 11-18 years groups, the infection rates were 24.6%, 27.2%, 32.9%, and 34.8%, respectively[25]. Another study in healthy school children noted a slightly higher infection rate with an average annual rate increase of 3.28% in Saudi Arabia[27].Children whose parents are infected withH. pylorihave much higher infection rates than children whose parents are not infected[12], suggesting that intra-familial transmission plays an important role inH. pyloritransmission. However, child infection rates in North America, parts of Europe and Japan remain very low (1.8%-10%)[22,26,28].

Table 2 Common Helicobacter pylori intra-familial transmission routes1 and their prevention

Gastric atrophy is also noticed in children and even found in very young children,and earlier small-sized study had indicated that atrophy was present in 0-72% of the samples studied, as summarized by Dimitrov and Gottrand[29]in 2006. Recent studies revealed that its prevalence in various countries may correspond to the infection rate at adulthood. Studies in Chinese, Japanese, and Mexican children revealed that atrophy was present in 21.7% (among 524 cases), 10.7% (among 131 cases), and 9% (7 out of 82 cases) of children infected withH. pylori, respectively[25,30,31]; intestinal metaplasia was present in 6% ofH. pylori-infected Mexican children[30]. In another study in Tunisian children, an area with a high infection rate, gastric atrophy was detected in 9.3% (32 out of 345 cases) of the total study population, and in 14.5% (32 out of 221 cases) of chronic gastritis patients[32]. However, atrophy was not found in 96 cases of Brazilian children studied, and was rare in 66 cases of French children infected withH. pylori[33,34]. Although further investigation is necessary, these data point out the possibility that atrophy and intestinal metaplasia are probably more common and are presented in similar ways to adulthood infection. Thus, active intervention based on infection situations are warranted. However, its natural course and consequences, risk potential for cancer, and factors that contribute to atrophy remain to be studied.

Management ofH. pyloriinfection in children is recommended based on riskbenefit ratios. Depending on different locations and infection rates, the joint ESPGHAN/NASPGHAN guidelines for the management ofH. pyloriin children and adolescents (Update 2016) recommended against a ‘‘test and treat’’ strategy forH.pyloriinfection in children, but recommend testing and treatingH. pyloriin children with gastric or duodenal ulcer diseases[28]. Guidelines provide recommendations primarily based on and for the setting of North America and Europe, which have very low and decreasingH. pyloriinfection rates. It therefore may not apply to other parts of the world that have highH. pyloriinfection rates in children and adolescents, and to those areas with only limited resources for healthcare.

In countries whereH. pyloriinfection and gastric cancer are prevalent, such as in Asia, the Middle East, part of Europe, Africa, Latin American and in many developing countries, a “screen and treat” strategy to eradicateH. pyloriinfection for gastric cancer prevention is encouraged, as it is cost-effective[9,10,22-24]. Similar to this notion, the 2016 Japanese-revised guidelines for the management ofH. pyloriinfection recommend eradicatingH. pylorifor adolescence in order to control infection for the next generation (6.2.2. Recommendation: 1, Evidence level: B). It also suggests that“undergoing eradication therapy before becoming a parent can be a measure against transmission to the next generation by preventing intra-familial infection”[12]. In the Bangkok consensuses report of 2018, theH. pylorimanagement in ASEAN, Statement 4 recommended that “eradication ofH. pylorireduces the risk of gastric cancer, and family members of gastric cancer patients should be screened and treated”[9]. These guidelines provided the notion that family infection control is a critical step inH.pylori-induced disease prevention. Future investigations are warranted to obtain data and formulate policies for whole family-basedH. pylorieradication. Precautions should be excised to avoid over-testing uninfected or missing infected individuals.Urease breath tests and serological or stool antigen tests might be cost-effective and efficient applications.

One concern inH. pyloritransmission prevention is its re-infection or recrudesces after eradication, and studies have shown various results in different geographic areas that have slightly different outcomes, ranging from 0-10%[9,35-37]. In a medium prevalence area, a study found that 1-year and 3-year recurrence rates ofH. pyloriinfection in adults after eradication therapy were 1.75% and 4.61%, respectively; low income and poor hygiene condition are independent risk factors of recurrence[35]. A systemic review noted that global annual recurrence, reinfection and recrudescence rates ofH. pyloriwere 4.3% (95%CI: 4-5), 3.1% (95%CI: 2-5) and 2.2% (95%CI: 1-3),respectively[36]. This variation also depends on the country, as one Korean study indicated that the long-term (37.1 mo) average reinfection rate was 10.9%, and the annual reinfection rate was 3.51%[37]. However, few reports studied whether there was any difference when only the infected individualversusthe entire infected family was treated.

A small observational study by Sariet al[38]in 2008 in Turkey found that out of 70 patients with whole family (175 members)H. pyloritesting and eradication, the recurrence rate was 7.1% 9 mo after treatment. In another 70 patients, as a control,when only the infected patient was eradicated but the whole family (190 members)infection was not treated, the recurrence rate was 38.6% 9 mo after treatment. These results suggest that treatment of the whole infected family is of great value in controllingH. pylorire-infection and preventing recurrence. There are currently no similar large-scale observational studies on this, and results from such studies will provide important information in guiding comprehensive prevention ofH. pyloriinfection in a whole family-based approach. They will also serve as part of “precision and integratedH. pylorieradication medical practice”, as it has also been suggested that eradication of gastric cancer is now both possible and practical[39], and that gastric cancer is a preventable disease[40]throughH. pylorieradication.

WHY DO WE NEED THIS STRATEGY? THE MECHANISM: H.PYLORI VIRULENCE FACTORS AND GASTRIC CANCER

H. pyloriinfection in whole families is often caused by the same or variant strains spreading among family members, but there are also multiple-strain infections,indicating that outside sources are also involved[20,41,42]. Further studies are therefore required to clarify the importance of both routes. The whole family cluster infection model can also explain the facts that single or multiple members of the infected family have gastric mucosal pre-cancerous lesions and gastric cancer at different periods of time in their life, suggesting that co-infection, not hereditary factors, plays a more important role in disease progression.

How and why long-termH. pyloriinfection results in the development of precancerous conditions and cancer remains to be defined[43-48]. Upon infection,H. pyloritriggers numerous cellular inflammatory and oncogenic signaling pathways, with list expanding, which includes but is not limited to NF-κB, AP-1, TGF-β, Wnt, Stat3, and p53 pathwaysetc. It also causes either genetic or epigenetic changes in various cell types, such as low frequency mutation, abnormal microRNAs and long non-coding RNA expression, histone modification, and DNA methylation[43,47,48]. Bacterial and host factors are both involved in initiating chronic inflammatory processes, which impact host epithelial cells, immune cells, fibroblasts, stem cells and their interacting microenvironment. This results in disturbing critical cellular events including cell division, proliferation, apoptosis, migration and DNA repair, and ultimately causes cellular and oncogenic transformation[43,44,47,48]. Recent studies on interactions ofH.pyloriwith Lgr5, CCK2R-positive gastric stem cells, or their progenitor cells and their microenvironment have shed light on the possible role ofH. pylorion atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia and gastric cancer.H. pyloristrains carryingcagPAI with CagA- and VacA-positive are also important for these processes[43-48].

H. pyloricytotoxins CagA and VacA are major virulence factors and molecular basis for disease pathogenesis, despite thatH. pyloripossesses other virulence factors. These include outer membrane proteins, outer inflammatory proteins, and duodenal ulcerpromoting factors[9,43,47,48].H. pyloristrains that carrycagPAI with CagA and VacA positivity cause severe gastric inflammation, which are prone to either tissue damage or neoplastic transformation, are high-risk strains of gastric cancer, and the role of the CagA protein is critical in these processes[48-51]. A few important experiments have provided evidence:In vivoexperiments incagAtransgenic mice using artificially synthesized whole sequences of thecagAgene resulted in the development of gastric cancer and other gastrointestinal and hematological tumors in mice withoutH. pyloriinfection. This suggests that it has oncogenic characteristics[49], and that mutation incagAabolish the tumor-initiating effects in animal models[50]. CagA- and VacApositive strains are the major global forms ofH. pyloriinfection, corresponding to their high prevalence in pre-cancerous lesions and gastric cancer incidences[51].

Gastric cancer includes intestinal and diffuse types according to Lauren classification. Intestinal type of gastric cancer generally have distinct ductal structures, which are more common in older men and manifest with a Correa carcinogenesis pattern. Diffuse type of gastric cancer include diffuse growths, closely related to genetic inheritance, are more common in young women, and are prone to lymph nodes and distant metastasis, but both types of gastric cancer are closely related toH. pyloriinfection[52].H. pylori-negative gastric cancers are rare in Japan[53],and may also be the case in other parts of highly infected areas if strict populationbased observation are conducted. Although other factors, except in a small portion of genetically-related gastric cancers, such as lifestyle, diet, chemical factors, high salt,and changes in stomach flora or microecology, may also be involved in the occurrence and development of gastric cancer. Current comprehensive results from epidemiology, basic, clinical and population-based observations have demonstrated thatH. pyloriinfection remains the single most important pathogenic factor for gastric cancer initiation and development[1,9,43,47].

ERADICATION OF H. PYLORI INFECTION IN A WHOLE FAMILY-BASED APPROACH AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

The most efficient way to controlH. pyloriinfection would be a specific vaccine;however, the development of anH. pylorivaccine has suffered setbacks, and is still in the laboratory testing stage[54], so there is no hope for a clinical application in the next 5-6 years.

Traditionally, two strategies are available in the management ofH. pyloriinfection:(1) “test and treat” is recommended for young patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia, but not applicable to patients with alarm symptoms or older patients; and(2) "screen and treat" is for patients with a family history of gastric cancer, having alarm symptoms and localized in gastric cancer-prevalent areas[1,9,10]. In Western countries, the benefits for population-basedH. pyloritest and treatment strategies may be small due to low and decliningH. pyloriinfection rates, and very low rates of related diseases such as peptic ulcers, pre-cancerous lesions and gastric cancer. For other areas, such as Asia, the Middle East, part of Europe, Africa, Latin American and in many developing countries that have high infection rates and related diseases, it is beneficial, cost-effective, and worth population-based screening and intervention(Table 1)[1,2,9,10,12].

These two important strategies provide general guidelines for managingH. pyloriinfection, and will continue guiding the globalH. pylorieradication program.However, clinical applications have found that they have some shortfalls and may need refinement, mostly due to the fact that they are not easily manageable during practice, and are affected by patient compliance, selection of treatment population,cost-benefit estimation, and that infections are difficult to control from the source(Table 1)[1,9,10]. In addition, they focus on treating individual patients, and do not emphasize screening and eradicating an entire family of infected members. The advantage of this approach is that they solve the problem of visiting patients, but do not underscore subsequent reinfection and continued infection by other infected family members; nor do they address issues of non-visiting, untreated, but infected family members. This practice also does not integrate associated gastric mucosal lesions, and disease progression that was already present in the infected family members. In the long run, due to the dynamic and progressive nature of infection, it is difficult to controlH. pyloriinfections from the source, and subsequently increases healthcare burden at later stages of disease. Therefore, a whole family-based eradication strategy would provide help in resolving the above-mentioned problems as an additional approach. For example, “screen, identify, treat whole family infected members and follow up” would be suitable for both scenarios, as the attention and resource could be concentrated and shifted to the high-risk portion of the population for disease prevention and intervention, therefore relieving overall healthcare burden at later stages[13](Figure 1).

The superiority of whole family-based strategy over population- or communitybased strategies is that the new strategy actively screens and treats infected individuals or families, which is a high-risk infection population, and family members that have high stakes are easily motivated and engaged. This makes it easier to monitor infected patients for pre-cancerous lesions and follow-ups[13]. Preliminary results in practice in a whole family-based setting suggest that patients and family members have high satisfactory rates and good compliance, which deserves further investigation and refinement[13]. One concern for this strategy is that it might overscreen family members that are not infected. However, as non-invasive serological tests, urease breath tests, and stool antigen tests are more affordable, accessible and efficient, this strategy provides a practical solution for whole familyH. pyloriinfection screening and eradication, especially for high-risk populations (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Flow chart of whole family-based Helicobacter pylori infection management strategy. In a typical gastroenterology clinic, visiting patients arequestioned for symptoms and signs, and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is tested. If the patient is H. pylori positive, the related family members arerecommended to test H. pylori either by serological, stool antigen or urease breath tests, or both; this could include parents, spouses, children, or other members living in the same household. The infected family members are recommended to treat the infection, ideally at the same time, and follow up. If patients are confirmed as H.pylori negative, just following up without treatment is required. 1Screen test for family members can be urease breath tests, or various antibody tests. H. pylori:Helicobacter pylori.

H. pyloridrug resistance is another concern for massive eradication, as the drug resistance conditions are related to local bacterial resistance patterns and previous antibiotic intake, so the guidelines are not generalizable for every country. Current guidelines recommend regimens including proton pump inhibitor-based triple and quadruple therapies[1,9,10]. They should be applied to the whole family eradication setting, and susceptibility tests either byH. pyloricultures or molecular biology assays are recommended for certain clarithromycin-, levofloxacin-, and metronidazoleresistant regions as well as first-time failed patients. Notably,H. pyloriresistance to amoxicillin, tetracycline and furazolidone is very low[1,9,10]. Safety and benefits for children during eradication have to be considered carefully during individual practice based on local infection status[28].

Serological markers for detecting gastric pre-cancerous lesions and gastric cancer are currently not available, so searching and validating such candidate markers are important and urgent future working directions. The available alternative assays such as pepsinogen (Pg) I, II and anti-H. pyloriantibody testing are instrumental for identifying patients at increased risk for gastric cancer. However, the PgI/PgII ratio should not be used as a biomarker of gastric neoplasia as recommended[1].Genotyping forH. pylorivirulence strains involve testing CagA- and VacA-positive strains as high-risk serological markers, combined with gastrin, pepsinogen testing and gastroscopy in a clinical setting are currently the most useful approaches for gastric lesion screening and diagnosis. These provide feasible ways to identify highrisk populations and detect early gastric pre-cancerous lesions and cancer.

CONCLUSION

H. pyloriinfection is an infectious disease and family-based disease. In addition to“test and treat” and "screen and treat" strategies, adoption of a third, novel whole family-basedH. pyloriinfection prevention and intervention strategy as an additional approach has been described here. This new strategy is designed to screen, identify,treat and follow up on all high-risk family members, and to prevent or reduce the risk of bacterial transmission, gastric mucosal lesion progression and gastric cancer incidence, while saving on medical costs for later stages. This “whole family- or household-basedH. pyloriprecision and integrative eradication strategy” will be practical not only for highly infected communities, but also for those with low infection rates. Therefore, after proper refinement and debate, this strategy will be an important way to help reduce the source of transmission, improve public awareness of infection, and ameliorateH. pyloriinfection-related disease and gastric cancer burden for society.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author is grateful to the staffs of the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, People’s Hospital of Zhengzhou University for their valuable assistance with this work.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Is aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation beneficial in acute pancreatitis? A meta-analysis of randomized control trials and cohort studies

- Technetium-99m-labeled macroaggregated albumin lung perfusion scan for diagnosis of hepatopulmonary syndrome: A prospective study comparing brain uptake and whole-body uptake

- Predictors of outcomes of endoscopic balloon dilatation in strictures after esophageal atresia repair: A retrospective study

- Serum N-glycan markers for diagnosing liver fibrosis induced by hepatitis B virus

- Double-balloon endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for patients who underwent liver operation: A retrospective study

- Prognostic factors and predictors of postoperative adjuvant transcatheter arterial chemoembolization benefit in patients with resected hepatocellular carcinoma