Double-balloon endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for patients who underwent liver operation: A retrospective study

2020-03-23RyoNishioHirokiKawashimaMasanaoNakamuraEizaburoOhnoTakuyaIshikawaTakeshiYamamuraKeikoMaedaTsunakiSawadaHiroyukiTanakaDaisukeSakaiRyojiMiyaharaMasatoshiIshigamiYoshikiHirookaMitsuhiroFujishiro

Ryo Nishio, Hiroki Kawashima, Masanao Nakamura, Eizaburo Ohno, Takuya Ishikawa, Takeshi Yamamura,Keiko Maeda, Tsunaki Sawada, Hiroyuki Tanaka, Daisuke Sakai, Ryoji Miyahara, Masatoshi Ishigami,Yoshiki Hirooka, Mitsuhiro Fujishiro

Abstract BACKGROUND Double-balloon endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (DB-ERC) is widely performed for biliary diseases after reconstruction in gastrointestinal surgery, but there are few reports on DB-ERC after hepatectomy or living donor liver transplantation (LDLT).AIM To examine the success rates and safety of DB-ERC after hepatectomy or LDLT.METHODS The study was performed retrospectively in 26 patients (45 procedures) who underwent hepatectomy or LDLT (liver operation: LO group) and 40 control patients (59 procedures) who underwent pancreatoduodenectomy (control group). The technical success (endoscope reaching the choledochojejunostomy site), diagnostic success (performance of cholangiography), therapeutic success(completed interventions) and overall success rates, insertion and procedure(completion of DB-ERC) time, and adverse events were compared between these groups.RESULTS There were no significant differences between LO and control groups in the technical [93.3% (42/45) vs 96.6% (57/59), P = 0.439], diagnostic [83.3% (35/42) vs 83.6% (46/55), P = 0.968], therapeutic [97.0% (32/33) vs 97.7% (43/44), P = 0.836],and overall [75.6% (34/45) vs 79.7% (47/59), P = 0.617] success rates. The median insertion time (22 vs 14 min, P < 0.001) and procedure time (43.5 vs 30 min, P =0.033) were significantly longer in the LO group. The incidence of adverse events showed no significant difference [11.1% (5/45) vs 6.8% (4/59), P = 0.670].CONCLUSION DB-ERC after liver operation is safe and useful but longer time is required, so should be performed with particular care.

Key words: Biliary tract diseases; Double-balloon enteroscopy; Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; Hepatectomy; Liver transplantation; Risk management

INTRODUCTION

It is difficult to perform endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for biliary diseases in cases with surgical gastrointestinal reconstruction, and if necessary percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage or reoperation was performed alternatively. In recent years, however, techniques for balloon-assisted ERCP,particularly short-type double-balloon endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (DBERC), have been widely reported[1-4], with utility shown by rates for the endoscope reaching the duodenal papilla or hepaticojejunostomy site of 89%-99.1% and procedural success rates of 93%-100%. But most of reports have discussed Roux-en Y,Billroth II, and pancreatoduodenectomy (including pylorus-preserving and subtotal stomach-preserving procedures) as postoperative reconstruction methods[5-8].

We have experienced many cases requiring DB-ERC after hepatectomy or living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) performed in our hospital[9,10]. Reports on DB-ERC for anastomosis site stenosis after LDLT suggest endoscope insertion and procedural success rates of 68%-85% and 78%-88.2%, respectively, which are slightly lower than for DB-ERC in other postoperative reconstruction cases[11-14]. This may be because endoscope insertion or therapeutic procedures are more difficult due to changes of hepatic volume and afferent loop length after LDLT. On the other hand, there are no reports on the results of DB-ERC in patients after hepatectomy with hepaticojejunostomy.

The aim of this retrospective observational study was to examine the results of DBERC in cases of hepatectomy with hepaticojejunostomy or LDLT [hereinafter referred to as liver operation (LO)]. As a control group, we selected patients who underwent pancreatoduodenectomy (including pylorus-preserving and subtotal stomachpreserving procedures) because they had choledochoduodenostomy, as for LO group,but no hepatectomy. The primary endpoint was the success rates of DB-ERC, and the secondary endpoints were the examination time and incidence of adverse events.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

The patients were 26 patients (45 procedures) in the LO group selected from 161 patients (222 procedures) who underwent DB-ERC from September 2011 to August 2018 at our hospital, and 40 patients (59 procedures) in the control group. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. DB-ERC was indicated if at least one of the following clinical symptoms or imaging findings was present: (1) Cholangitis;(2) Increase of hepatic enzymes; and (3) Abnormal findings for the biliary duct, such as bile duct stones, dilation of the bile duct and biliary stenosis in computed tomography or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. DB-ERC was not performed for the patients such as (1) a poor general status; (2) a poor status immediately after surgery; (3) clear perforation of the digestive tract; (4) serious cardiovascular or respiratory disease; or (5) no provision of informed consent.

Methods

DB-ERC: A short-type double-balloon endoscope was used in all examinations, with EI-530B endoscope (effective length: 1520 mm, working channel: 2.8 mm, FUJIFILM,Tokyo, Japan) or EI-580BT endoscope (effective length: 1550 mm, working channel:3.2 mm, FUJIFILM), and TS13101 over-tube (FUJIFILM). CO2insufflation was used in all procedures. The examination was performed by experienced endoscopists under conscious sedation with diazepam at 0.02 mg/kg and pentazocine at 7.5 to 15 mg.Sedation was added as needed based on the awake level during the procedure. For patients in whom sufficient sedation could not be ensured with diazepam and pentazocine, dexmedetomidine (loading at 6 μg/kg/h for 10 min, and then maintenance at 0.4 μg/kg/h) was used concomitantly[15]. After reaching the target site,the body position was changed to dorsal or abdominal to perform ERC.

For insertion to the bile duct, a 3.5 Fr catheter (PR-110Q-1, Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) or 3.9 Fr catheter (TRUEtomeTM, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA,United States) with a 0.025-inch guidewire (VisiGlide2TM, Terumo, Tokyo, Japan or RevoWave-SJTM, Piolax Medical Devices, Kanagawa, Japan) were mainly used. For expansion of the anastomotic region, a balloon catheter (ZARATM, Century Medical,Tokyo, Japan) or EPLBD (CRETMPRO GI Wireguided, Boston Scientific) were used.Extraction of stones was performed using a basket for stone extraction(FlowerBasketTM, Olympus Medical Systems) and a balloon catheter (Multi-3 VTMPlus,Olympus Medical Systems). If biliary stenosis, jaundice, cholangitis, or residual bile duct stones was suspected, a 7 Fr ERBD tube (ZimmonTM, Cook Medical, Tokyo, Japan or Medi-Globe Biliary Stent Set, Achenmühle, Germany), 5 Fr or 6 Fr ENBD tube[16](SilkyPassTM, Boston Scientific or EN-6S-260P32, Gadelius Medical, Kanagawa, Japan)and self-expandable metallic stent (Zilver635TM, Cook Medical or BilerushTM, Piolax Medical Devices) were placed. The study was performed after obtaining approval from the ethical committee of our hospital and performed according to the guidelines described in the Helsinki Declaration for biomedical research involving human patients [Clinical trial registration number: UMIN000025631 (UMIN); 2016-0032 (the institutional review board)].

Adverse events:Based on the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Guidelines[17], adverse events were defined as follows: Cholangitis, a fever of ≥ 38°C and increased biliary enzymes; pancreatitis, hospitalization prolonged for ≥ 2 d due to abdominal pain with hyperamylasemia; hemorrhage, overt bleeding or hematemesis/melena during procedures or a decrease of Hb 2 or higher; intestinal perforation; and other symptoms with hospitalization prolonged for ≥ 2 d.

Definitions of endpoints:The primary endpoint of this study was the success rate of reaching the hepaticojejunostomy site (i.e., technical success), successful cholangiography after cannulation to the bile duct (i.e., diagnostic success), completed interventions in the bile duct (i.e., therapeutic success), and completed diagnosis and interventions among all procedures (i.e., overall success). The secondary endpoint was the insertion and procedure time, and the incidence of adverse events. Insertion time was defined as the time required to reach the hepaticojejunostomy site, and procedure time as the time from reaching the hepaticojejunostomy site to removal of the endoscope.

Statistical analysis

Aχ2was used for analyses of the technical, diagnostic, therapeutic and overall success rates, and the incidence of adverse events. A Mann-WhitneyUtest was used for analyses of the insertion and procedure times. All statistical analyses were performed using BellCurve for Excel ver. 2.21 (Social Survey Research Information Co, Ltd.,Tokyo, Japan).

RESULTS

Patients

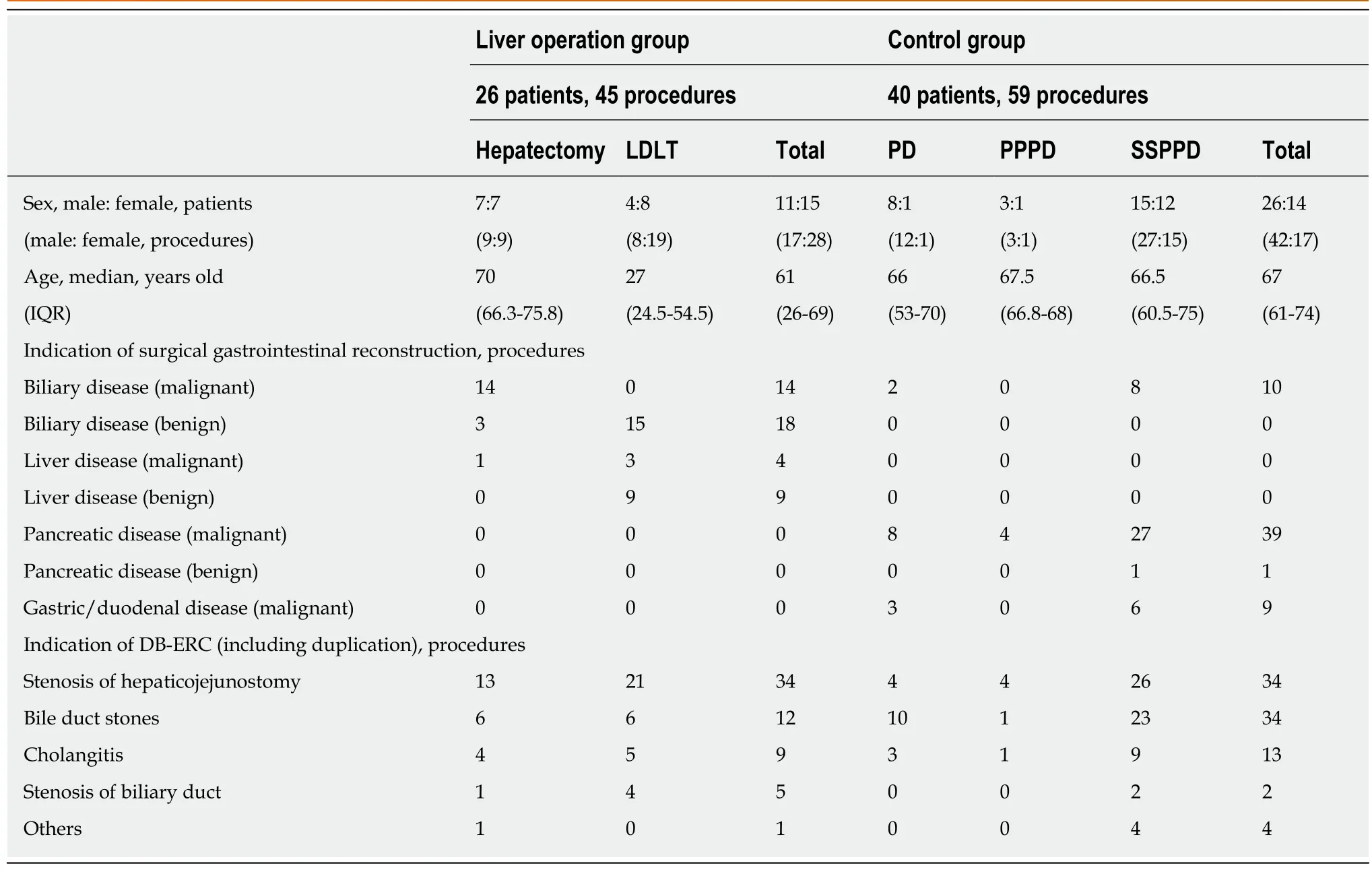

Backgrounds of the patients are shown in Table 1, respectively. The 26 LO patients (45 procedures) included 14 patients (18 procedures) who underwent hepatectomy,including right lobectomy (7 patients, 9 procedures), left lobectomy (3 patients, 4 procedures), right trisegmentectomy (1 patients, 2 procedures), and left trisegmentectomy (3 patients, 3 procedures); and 12 patients (27 procedures) who underwent LDLT, including left lobe graft (5 patients, 11 procedures) and right lobe graft (7 patients, 16 procedures). The 40 control patients (59 procedures) underwent pancreatoduodenectomy (9 patients, 13 procedures), pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy (4 patients, 4 procedures), and stomach-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy (27 patients, 42 procedures).

DB-ERC was underwent in 34 procedures for stenosis of hepaticojejunostomy, 12 for bile duct stones, 9 for cholangitis, 5 for stenosis of biliary duct, and 1 for others(foreign object in bile duct) in the LO group; and in 34 procedures for stenosis of hepaticojejunostomy, 34 for bile duct stones, 13 for cholangitis, 2 for stenosis of biliary duct, and 4 for others (3 for bile duct tumor, 1 for postoperative biliary fistula) in the control group, including duplication.

Success rates

The success rates are shown in Figure 1 and Table 2. There were no significant differences between the LO and control groups for the technical success [93.3%(42/45; 95%CI: 81.7%-98.6%)vs96.6% (57/59; 95%CI: 88.4%-99.1%,P= 0.439)];diagnostic success [83.3% (35/42; 95%CI: 68.6%-93.0%)vs83.6% (46/55; 95%CI: 71.7%-91.1%,P= 0.968)]; therapeutic success [97.0% (32/33; 95%CI: 84.7%-99.5%)vs97.7%(43/44; 95%CI: 88.2%-99.6%,P= 0.836)]; and overall success [75.6% (34/45; 95%CI:61.4%-85.8%)vs79.7% (47/59; 95%CI: 67.8%-88.0%),P= 0.617].

Two procedures in the control group were not included in the denominator of the diagnostic success because only observation of hepaticojejunostomy was needed. Two procedures in the LO group and 2 in the control group were not included in the denominator of the therapeutic success because the objectives of the examination could be achieved only with confirmation of bile duct images in cholangiography.

Failure in cholangiography was 7 procedures in the LO group and 9 in the control group. As the cause, stenosis of hepaticojejunostomy which could not been passed in 4 procedures, the examinations were abandoned due to difficulty in holding the endoscope at anastomosis sites in 2 procedures, hepaticojejunostomy site could not been found in 1 procedure in the LO group; stenosis of hepaticojejunostomy which could not been passed in 4 procedures, hepaticojejunostomy sites could not been found in 5 procedure in the control group.

Failure in completed interventions was both 1 procedure in the LO group and the control group. As the cause, the difficulty in holding the endoscope at anastomosis site in the LO group; stenosis of hepaticojejunostomy which could not been dilated in the control group.

Examination time

Examination times are shown in Table 3. The median insertion time (22vs14 min,P<0.001) and procedure time (43.5vs30 min,P= 0.033) were significantly longer in the LO group.

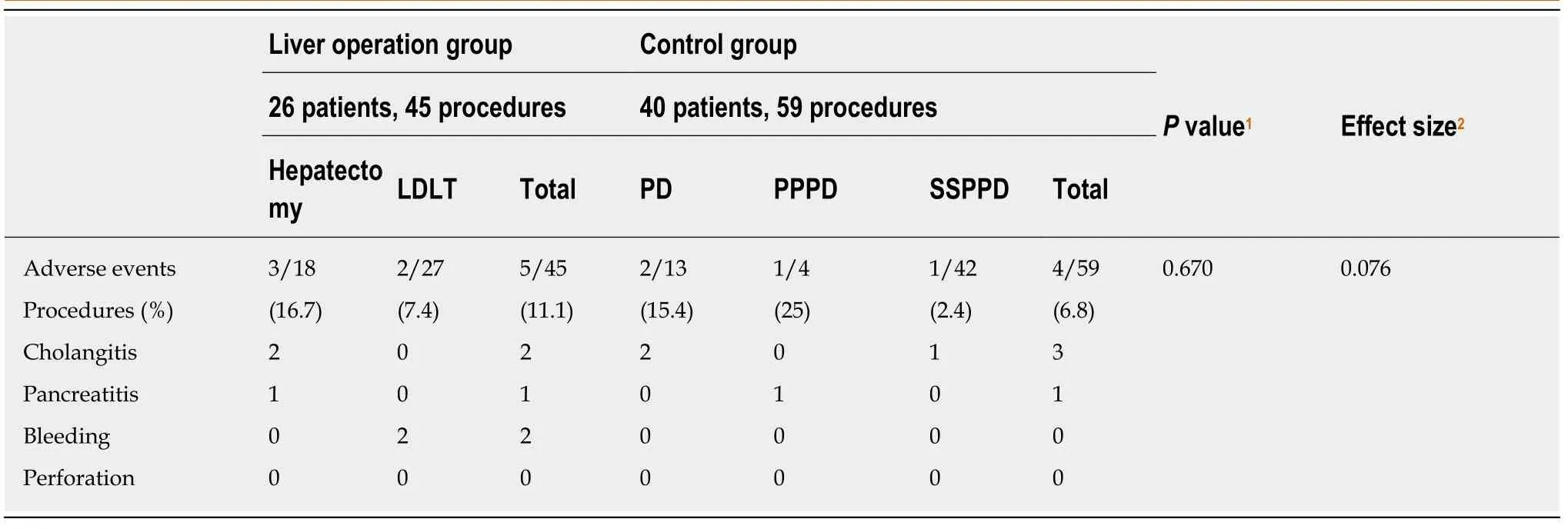

Adverse events

The incidence of adverse events is shown in Table 4. They did not differ significantly between the LO and control groups [11.1% (5/45; 95%CI: 4.8%-23.5%)vs6.8% (4/59;95%CI: 2.6%-16.1%),P= 0.670)]. Adverse events included cholangitis in 2, pancreatitis in 1, and bleeding in 2 in the LO group; and cholangitis in 3, and pancreatitis in 1 in the control group. Perforation was not occurred in both groups. All of these adverse events were improved with conservative treatment only.

DISCUSSION

Recently the utility of DB-ERC has been widely reported. Endoscopic treatment for postoperative biliary diseases such as stenosis of hepaticojejunostomy and bile duct stones is important because percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage and reoperation can be avoided. Some reports suggest technical, diagnosis, and therapeutic success rates of ≥ 90% regardless of the reconstruction method. Our success rates were slightly lower in the LO group, but equivalent to reports on DBERC for LDLT.

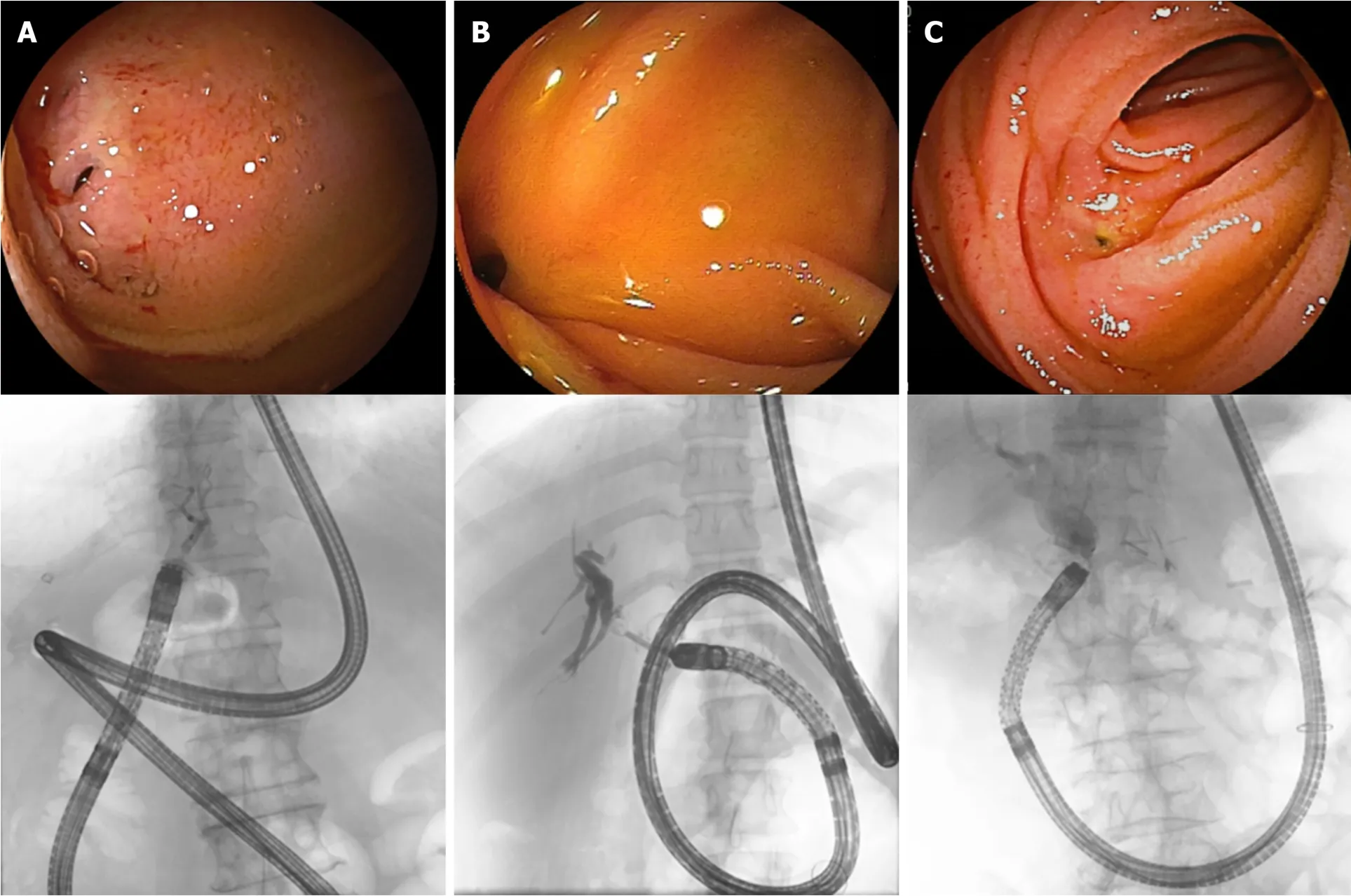

Table 1 Patients’ characteristics

Despite these successes, it is still challenging to perform DB-ERC with surgical gastrointestinal reconstruction due to difficulties with the procedure and development of adverse events. Itokawaet al[18]suggested that DB-ERC is difficult due to postoperative adhesion and bending of the bowel, and Yaneet al[19]showed that pancreatic indications, first ERCP attempt and without a transparent hood may be a cause of unsuccessful single-balloon enteroscope-assisted ERCP. When an endoscope is inserted in patients after hepatectomy or LDLT, there is a long distance to the anastomotic site, and also a high level of adhesion due to operative stress, a lower liver volume due to hepatectomy, changes in running of gastrointestinal tract due to successive hepatomegaly, and easy bending upon insertion of the endoscope. These factors increase the difficulty of DB-ERC for LO group compared to that after other postoperative cases. In DB-ERC, it is difficult to align the endoscope in a straight line and view the anastomotic site squarely in many cases, and this might affect the procedure time, as seen in the results of the current study (Figure 2, Table 2).Furthermore, the difficulty of DB-ERC may be different between patients who had right robe and left robe or underwent bisegmentectomy and trisegmentectomy, but there was no significant difference in this study due to the small number.

Many patients also require reexamination, even when procedures are successful.Tomodaet al[13]found a procedural success rate of 82.4% in balloon dilatation for stenosis of hepaticojejunostomy after LDLT, but 50% of these patients developed restenosis within 9.6 months. In a similar study, Kameiet al[20]found that 66.7% of cases developed restenosis.

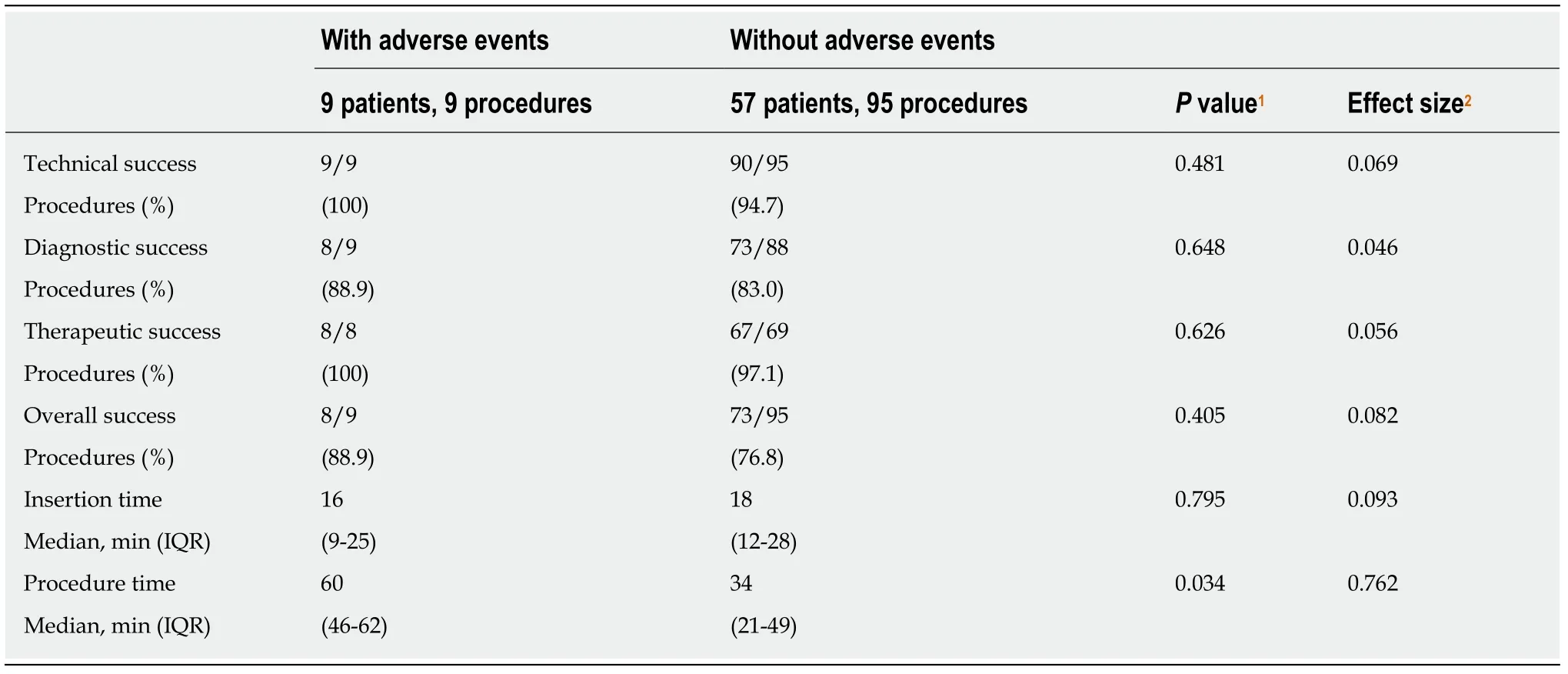

In our study, the incidence of adverse events was higher than that in past reports,and there were no significant differences in success rates and insertion time between patients with and without adverse events for the technical success [100% (9/9)vs94.7% (90/95),P= 0.481]; diagnostic success [88.9% (8/9)vs83.0% (73/88),P= 0.648];therapeutic success [100% (8/8)vs97.1% (67/69),P= 0.626]; overall success [88.9%(8/9)vs76.8% (73/95),P= 0.405]; and the median insertion time [16vs18 min,P=0.795], but procedure time was significantly longer in the patients with adverse events(60vs34 min,P= 0.034) (Table 5). No major differences in these factors compared to past reports. Therefore, anatomic factors in patients after hepatectomy or LDLT, as mentioned above, and longer procedure time might have caused more adverse events.Hyperamylasemia and pancreatitis after double-balloon endoscope have been reported, and inflated balloon or prolonged mechanical stress on the pancreas may be a cause of pancreatitis[21,22]. Similar processes might have happened in this study. As in regular ERCP, pancreatography is a risk factor for hyperamylasemia and pancreatitis,and pancreatography was performed in 3 of the 5 control procedures who developed hyperamylasemia or pancreatitis in this study. A long insertion time or pancreatography may cause more intense mechanical stimulation of the pancreas, even when the endoscope does not contact the duodenal papilla. However, only a few studies of adverse events after DB-ERC have been reported, and a further study is required to identify risk factors for adverse events in the future.

Figure 1 Flowchart of patients’ process. Technical success: Endoscope reached the hepaticojejunostomy site; Diagnostic success: Successful cholangiography after cannulation to the bile duct; Therapeutic success: Completed interventions in the bile duct; Overall success: Completed diagnosis and interventions among all cases.

In this study, we used two different endoscopes (procedures who underwent DBERC by EI-530B were 19 in the LO group and 17 in the control group, and by EI-580BT were 26 in the LO group and 42 in the control group), there were no significant difference in the success rates, procedure times and adverse events between two groups.

The limitations of this study include the retrospective design in a limited number of patients at a single facility; and inclusion patients who underwent DB-ERC twice or more; and the difference of diseases between the two groups; and inclusion patients who underwent DB-ERC with different endoscopes. Further accumulation of patients is required for a future study. Within these limitations, we conclude that DB-ERC is safe and useful for patients who underwent hepatectomy or LDLT, but the success rates may be slightly lower, the insertion and procedures time significantly longer,and the incidence of adverse events slightly higher than those after pancreatoduodenectomy.

In conclusion, DB-ERC is safe and useful for patients who underwent hepatectomy or LDLT, but particular care with the endoscope and obtaining informed consent are essential before DB-ERC is performed.

Table 2 Technical, diagnostic, therapeutic and overall success rates

Table 3 Insertion and procedure time

Table 4 Adverse events

Table 5 Differences of success rates, insertion and procedure time with or without adverse events

Figure 2 Endoscopic and fluoroscopic images of double-balloon endoscopic retrograde cholangiography. A: After right hepatic lobectomy; B: After livingdonor liver transplantation (right lobe graft); C: After pancreatoduodenectomy. These are endoscopic (upper) and fluoroscopic (lower) images of double-balloon endoscopic retrograde cholangiography. Endoscopic image: In A and B, procedures were difficult because the hepaticojejunostomy site was located near the edge of the visual field and close to the endoscope. In C, the hepaticojejunostomy site was located at the center of the visual field, and the distance from the endoscope was appropriate. Fluoroscopic image: In A and B, the endoscope bowed to the side of the removed liver, but no such bowing is observed in C.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

upon insertion of the endoscope. So particular care with the endoscope and obtaining informed consent are essential before DB-ERC is performed.

Research perspectives

DB-ERC will be performed safely and easily for patients who underwent any gastrointestinal reconstruction.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Is aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation beneficial in acute pancreatitis? A meta-analysis of randomized control trials and cohort studies

- Technetium-99m-labeled macroaggregated albumin lung perfusion scan for diagnosis of hepatopulmonary syndrome: A prospective study comparing brain uptake and whole-body uptake

- Predictors of outcomes of endoscopic balloon dilatation in strictures after esophageal atresia repair: A retrospective study

- Serum N-glycan markers for diagnosing liver fibrosis induced by hepatitis B virus

- Prognostic factors and predictors of postoperative adjuvant transcatheter arterial chemoembolization benefit in patients with resected hepatocellular carcinoma

- Mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor ameliorates steatosis in HepG2 cells by regulating hepatic lipid metabolism