How COVID-19 Impacts the Global Climate Change

2020-03-10郭敏行MinxingGuo

郭敏行 Minxing Guo

Introduction

On March 11 2020, the COVID-19 has been defined as a global pandemic by the World Health Organization, which means the infectious disease has a significant impact on the person-to-person spread in several countries. The virus has caused a lot of adverse effects around the world, such as economic stagnation and social disorder (Singh, 2020). Nevertheless, vasts of scholars claimed that the event caused a significant drop in CO2 emission since the outbreak started. Schwartz (2020) and Haines & Scheelbeek (2020) believe that the outbreak of COVID-19 is also part of the global climate change crisis, based on the fact that the epidemic is closely related to the greed of capitalism, and humankinds excessive demand for natural resources. This paper attempts to analyze the potential influence of the COVID-19 on climate change, mostly short-term, based on the existing materials. Because a wide range of conferences are canceled, the scholars fail to communicate face-to-face in public platforms recently (Viglione, 2020). Therefore, the paper is mainly based on data from governmental and NGOs reports retrieved from online websites. Although the article mainly describes short-term effects, the author will also try to illustrate the possible long-term influence of this epidemic in the last section.

Transport

Since the outbreak of the New Coronavirus, many countries have adopted strict travel restrictions (Pearce, 2020). Non-citizens are banned from entry to more than half of all the countries around the world, including Canada, France, Russia, India, Argentina, and Australia. Most of the remaining states, including China, Germany, the United States, and Brazil, have enforced policies and actions to prohibit entries of passengers from certain nationalities or countries of departure. These strict travel restrictions have caused considerable damage to the global travel industry, including the related hotel, catering, and aviation industries (UNWTO, 2020).

The governments and people started to avoid or restrict unnecessary travels, leading to a wide range of flight cancellations. Such strict migration restrictions and declining willingness of peoples long-distance traveling lead to a dramatic fall in global demand for aviation. Europe is suffering from a fall of air traffic by 80 to 90 percent, whereas the data in the US is roughly 60 percent (Pearce, 2020). In 2017, commercial aviation, as a whole, emitted around 859 million tonnes of CO2, which contributes to approximately 2% of human-made carbon emissions (IATA, 2018). Along with the reduction of driving and taking other public transports such as buses and trains, there is a significant drop in global carbon emission by the start of 2020, although Chinazzi et al. (2020) indicated that the travel restrictions had limited effect on interrupting the virus spreading.

In terms of medium and long period goal, the IATA set a global offsetting mechanism, called CORSIA (Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation). CORSIA aims to help address any annual increase in total CO2 emissions from international civil aviation above 2020 levels (IATA, 2018). If the carbon emission level in 2020 is much lower than it was supposed to be as assumed, along with no further explanation of CORSIA is stated by IATA, the aviation industry should contribute a lot to offset their negative environmental effect in the next decade.

Heavy Industries

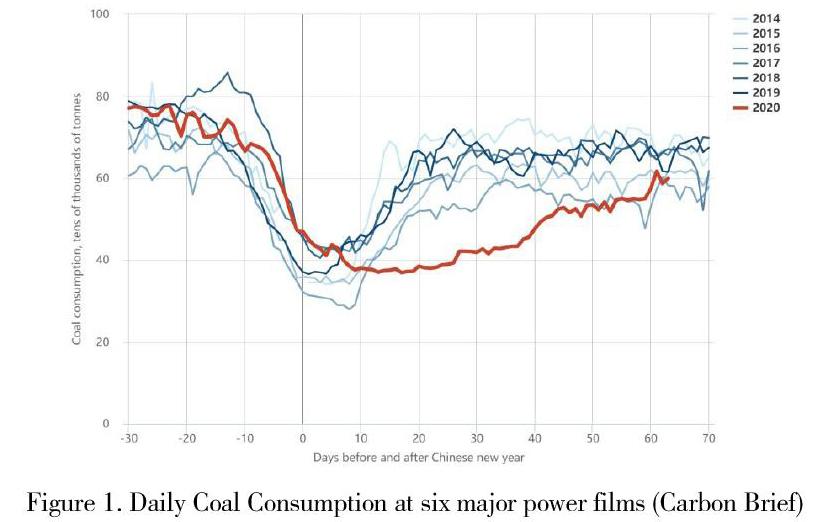

A quarter of the world population is quarantining at home, staying proper social distance from others (Schwartz, 2020). Aiming to control the virus outbreak, the Chinese government took mandatory actions to shut down the major production centers. China, as the biggest carbon emitter in the world (Tambo, Wang & Zhou, 2016), has witnessed a significant mitigation on environmental quality. Chinese New Year was supposed to be a ‘bad period for climate change because people tend to commute long-distance to their hometown for the reunion. And as the Spring Festival (Chinese New Year) is a legal holiday, many industries will radically start their new year plan, which consumes vasts of energies, unusually heavy industries. However, because of the COVID-19, compared to previous years, the carbon emission significantly declined during this period in 2020 (see Figure 1) (Myllyvirta, 2020).

As China is a manufacturing hub, the shortages of China-made products led to disruption in the worldwide supply chain, which affected almost all sections ranging from pharmaceuticals to automobiles (Gupta et al., 2019). The shortage in raw material of metal decreases the global production of cars. Ore production is a highly polluting industry, especially in developing countries like China (Xiao, Zong & Lu, 2015). The temporary mandatory shut down of factories also contributed to the reduction of NO2 and CO2. China, with its carbon emission reduction of 20% in this pandemic, provided a 6% diminishing of the global carbon emission solely (Myllyvirta, 2020). The tremendous decline in oil prices and the overall reduction in global industrial production caused major fall in the worldwide stock markets with markets falling more than 20% over a short period, and the risk of a global 2008-like recession is looming large (Bobdey & Ray, 2020; Gupta et al., 2020).

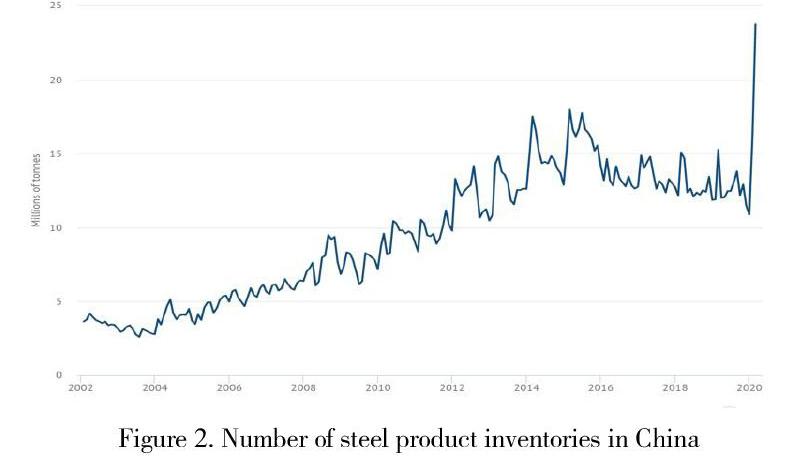

However, the reduction does not necessarily lead to a long-term change. Data form Carbon Brief show that metal companies in China kept unprecedentedly many storage of metal (see Figure 2), and are ready for a new rounds raw material supply.

Daily Lifestyles

Despite the change in aviation, there are many more alterations at the micro-level of peoples everyday lifestyles in this virus outbreak. A company called TomTom indicated unusually low traffic congestion in American urban areas since the end of March 8. Lower consumer spending points to weak US GDP growth in the first half of this year (The Economists, 2020). Globally, the GDP growth will slow down by 0.5%, from 2.9% to 2.4%, assumed by economists (Gupta et al., 2020).

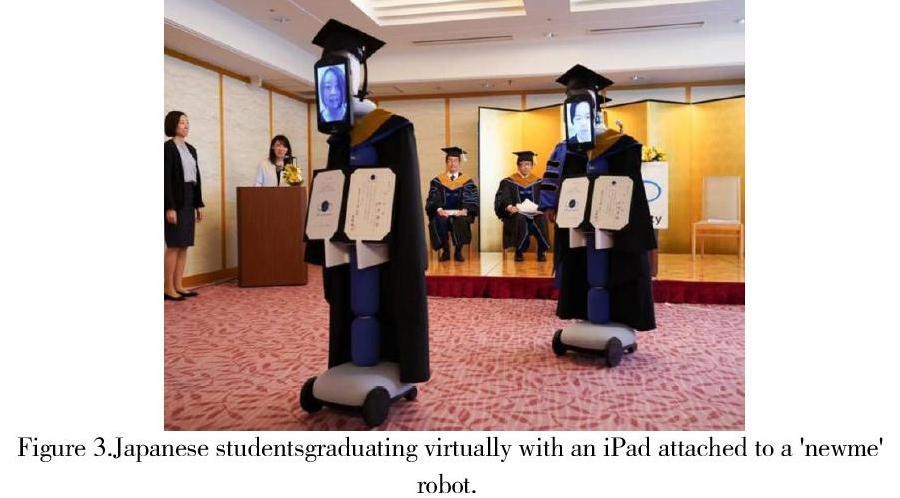

COVID-19 is often compared to SARS 2003 because of the similarities (Park, Thwaites & Openshaw, 2020). In China, a new concept called ‘non-contact economy is becoming more popular. Non-contact economy is introduced during the SARS in 2003, referring to the economy that is consuming without the necessity to contact other people, such as online shopping, non-contact express service, online working (especially software development), and artificial intelligence (AI). For example, although in recent years a few cities banned firework burning, this traditional activity still brings many pollutions by adding suspended particles into the atmosphere. In the United States, people also see a change in the style of big events. The biggest music festival Coachella, which was supposed to be held between April 10 and 12, is switched to live from traditional form (Warren, 2020). When it comes to education, DingTalk (Chinese company attached to Alibaba), Skype, and Zoom are broadly used for long-distance teaching and learning. In Japan, the Business Breakthrough (BBT) University held an unusual graduating ceremony with the help of intelligent interaction (see Figure 3).

I assume that the trend of the non-contact economy following COVID-19 will mitigate climate change, especially in East Asia, because the culture there encourages people to stay indoors. This cultural trait can be derived from the East Asians preference for lighter skin tones (Day et al., 2016). Additionally, East Asian people tend to behave better in indoor sport games (Culture & Society, 2009). That is to say, COVID-19 enables increasingly more people to drive less, buy less and enjoy more of staying home life thanks to the technology of network, intelligent interaction, blockchain, and artificial intelligence (Mallick, 2020).

Oil Industry

With the decreasing demand for commuting and non-essential travels, the International Energy Agency announced on February 15, 2020, that global oil demand growth fell to the lowest level since 2011. However, the oil price fell to the lowest since the Gulf war due to the Russia-Saudi Arabia Golf war. On March 6, due to Moscows refusal to support further production cuts in response to the impact of the new coronavirus epidemic, along with Russias dissatisfaction with the increase in US production that had squeezed Russias share since previous production restrictions, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and Russia did not agree to three-year production cut with a breakdown of negotiation. In response, OPEC decided to remove all restrictions on its own output (Sertin, 2020). The oil price collapse “will put downward pressure on the appetite for a cleaner energy transition,” International Energy Agency head Fatih Birol claims. Bloomberg columnist David Fickling calls the effects of the oil crash “nuanced”. However, he adds that overall theyre “positive for decarbonization” — and he doesnt think emissions will be set to bounce back again after this downturn the way they have in the past.

The oil shale industry is suffering from an unprecedented, severe crisis due to the oil price fall. The plunge in international oil prices has severely banged the US shale oil industry. On April 1, American shale oil company Whiting Petroleum applied for bankruptcy protection to the court and became the first bankrupted US shale oil company since the collapse of international oil prices. The extracting and processing of shale oil is criticized as contributing most human-made CH4, and CH4 is known as a ‘giant killer gas that has much more impact on global warming than CO2 per unit (see Figure 4).

Nevertheless, the collapse of oil prices may lead to hardness in clean energy development due to the lack of interests. Furthermore, governments and companies are less willing to support low-carbon technology and sustainable energy.

Conclusion

This paper mainly focuses on how the COVID-19 effects on a short-term basis. Due to the limited and highly changing dynamic of the epidemic, the author cannot achieve adequate materials for analysis. In the first three months of 2020, the planet is witnessing an excellent mitigation on worsening climate change. Less travel and falling demand for industrial products may be the primary cause. In terms of the macro-level, limitations of international and domestic travels, and mandatory pausing industry may be the reason. However, how the outbreak may affect long-term climate change is an unsettled issue, depending on how NGOs and governments further consider the actions to balance energy demands for economic recovery and sustainable development. Lars Peter Riishojgaard, the Geneva-based UN Meteorological Organizations infrastructure department, said any reduction in pollution and carbon dioxide emissions might be temporary (UN News, 2020). He said: ‘The pandemic will end at a particular moment, and the world will start to function again. At the same time, carbon dioxide emissions will rise again, maybe, maybe not reach the same level. Everyone can think of the epidemic as a scientific experiment: what will happen if we turn off everything suddenly? This may cause some people, and perhaps some governments, to reflect. Neverthe less, the long-term effect of COVID-19 to global warming may be underestimated by many scholars. By bringing a higher goal of offsetting aviation carbon emission, altering peoples living style to some extent, and changing the potential trajectory of governments and NGOs cooperating to fight climate change (Logan, 2020), the pandemic may activate movements of towards a more eco-friendly development. However, there is still a gap between the conclusion and adequate evidences. Related studies can be conducted to discover the overall relationship of pandemic and climate change based on previous outbreaks. Besides, whether the COVID-19 will impact the global population distribution and growth rate remains unclear. In the future, researches are required to be done in how governments and NGOs responding to the epidemic on a medium or long-period basis.

References

[1]Bobdey, S., Ray, S., Going viral–Covid-19 impact assessment: A perspective beyond clinical practice. Journal of Marine Medical Society. 2020;22(1):9.

[2]Culture & Society. (2009). 3rd Asian indoor games end: Vietnam ranks second behind China. Vietnam News Briefs.

[3]Chinazzi, M., Davis, J. T., Ajelli, M., Gioannini, C., Litvinova, M., Merler, S., ... & Viboud, C. (2020). The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science.

[4]Culture & society: 3rd Asian indoor games end: Vietnam ranks second behind china. (2009, ). Vietnam News Briefs

[5]Day, A. K., Wilson, C. J., Hutchinson, A. D., & Roberts, R. M. (2016). Acculturation, skin tone preferences, and tanning behaviours among young adult Asian Australians. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 37(5), 421-432. doi:10.1007/s10935-016-0442-7

[6]Gupta, M., Abdelmaksoud, A., Jafferany, M., Lotti, T., Sadoughifar, R., & Goldust, M. (2020). COVID-19 and economy. Dermatologic Therapy, , e13329. doi:10.1111/dth.13329

[7]Haines, A., & Scheelbeek, P. (2020). The health case for urgent action on climate change. Bmj, 368, m1103. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1103

[8]Logan, L. (2020). democrats, advocates eye low-carbon steps in coronavirus response. Inside EPA Weekly Report, 41(12)

[9]International Air Transport Association. (2018). Fact Sheet--Climate Change & CORSIA. Retrieved from https://www.iata.org/contentassets/c4f9f0450212472b96dac114a06cc4fa/fact-sh eet-climate-change.pdf

[10]Myllyvirta, L. (2020). Analysis: Coronavirus temporarily reduced Chinas CO2 emissions by a quarter. Carbon Brief. Retrieved from https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-coronavirus-has-temporarily-reduced-china s-co2-emissions-by-a-quarter

[11]Park, M., Thwaites, R. S., & Openshaw, P. J. M. (2020). COVID‐19: Lessons from SARS and MERS. European Journal of Immunology, 50(3), 308-311. doi:10.1002/eji.202070035

[12]Pearce, B. (2020). COVID -19 Updated Impact Assessment. Retrieved from the IATA wesbite:https://www.iata.org/en/iata-repository/publications/economic-reports/thi rd-impact-assessment/

[13]Schwartz, S. A. (2020). Climate change, covid-19, preparedness, and consciousness. Explore (New York, N.Y.), doi:10.1016/j.explore.2020.02.022

[14]Sertin, C. (2020). COVID-19 and oil price war could slash two-thirds of 2020 oil and gas project sanctioning. OilandGasMiddleEast.Com

[15]Singh, Z. D. (2020). COVID-19 should make us re-imagine the world order. Economic & Political Weekly,

[16]Tambo, E., Duo-quan, W., & Zhou, X. (2016). Tackling air pollution and extreme climate changes in china: Implementing the Paris climate change agreement. Environment International, 95, 152-156. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2016.04.010

[17]The Economist. (2020). Clear thinking required; covid-19 and climate change. 434(9187), 70.

[18]The Economist (2020). Spluttering; covid-19 and the economy. 434(9185), 19.

[19]Translated by ContentEngine LLC. (2020). The world's parate for the covid-19 cleared the skies and reduced global warming. CE Noticias Financieras

[20]United Nations . (2020). COVID-19 effect casts cloud over weather alert accuracy: UN sky watchers. UN News. Retrieved from https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/04/1060772.

[21]UNWTO. (2020). Impact assessment of the COVID-19 outbreak on international tourism. Retrieved from: https://www.unwto.org/impact-assessment-of-the-covid-19-outbreak-on-internati onal-tourism

[22]Viglione, G. (2020). A year without conferences? how the coronavirus pandemic could change research. Nature, 579(7799), 327-328. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00786-y.

[23]Warren, L. (2020). COVID-19 and climate change will reshape festival fashion. Sourcing Journal (Online).

[24]Xiao, Q., Zong, Y. & Lu, S. (2015). Assessment of heavy metal pollution and human health risk in urban soils of steel industrial city (Anshan), Liaoning, Northeast China. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 120, 377-385. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.06.019

(the University of British Columbia V6T1Z4)