MANAGING THE TREASURIES OF THE GODS–ADMINISTRATION OF THE KÙ.AN IN UR III UMMA*

2020-02-25XiaoliOuyang

Xiaoli Ouyang

History Department,Fudan University,Shanghai

ABSTRACTS The term KÙ.AN is attested in more than a dozen administrative records from Umma of the Ur III period (c.2112–2004 BC).An analysis of those records with respect to the context,the formula,and the people involved indicates that KÙ.AN may well refer to a treasury where treasures of a deity were kept in a temple.Such an analysis also sheds new light upon the function and organization of this kind of treasuries within the administrative framework of the Umma temples.

In a number of administrative records from the Umma province and dated to the second half of the Ur III dynasty (c.2112–2004 BC),the Sumerian term KÙ.AN appears in association with objects of silver,other metals (gold,bronze,and copper),and precious stones delivered to the local patron godara(mu-kuxdšára).1Sallaberger 1993,vol.I,237.In addition to the attestations listed by Sallaberger,2Ibid.KÙ.AN features in more Umma texts that the present author collected in the Database of Neo-Sumerian Texts (=BDTNS) and the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (=CDLI)3See,respectively:http://bdts.filol.csic.es,and:https://cdli.ucla.edu (both:04.04.2019).and summarized in the appendix.

The term KÙ.AN has two possible readings.It can on the one hand be analyzed as kù-dingir,thus meaning“silver/precious metal of gods.”On the other hand,KÙ.AN may render the compound azag/k,which in turn corresponds to the writing of an-zag attested in a number of accounts from the Inanna temple in Ur III Nippur.The phrase an-zag probably means“treasure,”based on the context.4Sallaberger 1993,vol.I,237 with previous literature,with Civil 1983,esp.236.Therefore,the two meanings of KÙ.AN turn out to be interrelated despite their different readings.On account of the uncertainty of its reading,this article retains the written form KÙ.AN throughout.5That being said,the reading of azak for KÙ.AN is very likely in light of the attestations such as KÙ.AN-ka ku4-ra/ ku4-dam/ ba-an-ku4,where -a at the end of KÙ.AN-ka serves as a locative marker.

At first glance,the majority of the texts featuring KÙ.AN assume the form of short or long lists of objects.But an analysis of them with respect to the context,the formula,and the people involved indicates that KÙ.AN may well refer to a treasury where treasures of a deity were kept in a temple.Furthermore,such an analysis sheds new light upon the function and organization of such treasuries within the administrative framework of the Umma temples.

1.KÙ.AN in Connection with Livestock

The term KÙ.AN occurs in connection with livestock offerings in five Umma records:SNAT 409 (AS 8 iv),Aegyptus 10,271 30 (IS 1 xi),AAICAB 1/3,Bod.S 168 (IS 2 xi),AAICAB 1/3,Bod.S 225 (no date),and Cohen 1993,181 RBC 2540(no date).6Translation by Cohen (1993,181).Although no date appears on the tablet,Cohen dates it to AS 5 viii and identifies the festival as the eitiaš-festival without an explanation.Sallaberger (1993,vol.II,152) adopts the same date,as do BDTNS and CDLI.The first two records present a long list of sheep and goats expended by Alulu7He is a well-known animal fattener who was active in Umma,where he supplied animals for cultic purposes:cf.Stępień 1996,108–112.as offerings for the festivals ofara,the patron god of Umma,in month iv and month xi respectively.8Sallaberger (1993,vol.I,236) identifies the festival in month iv as the most important one on the cultic calendar of Umma.SNAT 409 enumerates seventy-six sheep and goats,9Sallaberger (ibid.,236–244) discusses this text in detail.According to him (ibid.,237),it records not a one-time expenditure,but the total number of livestock expended for the festivals of ara throughout the entire calendar year.while Aegyptus 10,271 30 contains a list of fifty-two animals.Both texts feature a cluster of fifteen identical or similar offerings,which includes an offering of one sheep for the KÙ.AN.10Sallaberger 1993,vol.II,152.The differences are as follows:1 sheep for the a-tu5-a dšára ù sískur šà é-a,“the ritual bath of ara and the siskur-sacrifice in the temple”(SNAT 409 Obv.ii:14) vs.a-tu5-a dšára (Aegyptus 10,271 30:Rev.1);and 1 sheep for the ki AN.A.IR-da (SNAT 409:Obv.ii:17) vs.ki a gíd-da (Aegyptus 10,271 30:Obv.16).The discrepancy of the last pair is noted by Sallaberger(1993,vol.I,240),but without an explanation.In both texts,the sheep for the KÙ.AN appears together with the offerings for special locations,such as the ká gu-la,“the main gate (of a temple),”or those made during ritual actions such as the a gub-ba“the setting up of the water (containers),”11Cf.ibid.,238.and the SAL+HÚB-e a lá-a“the transportation of water in wooden bowls.”12Cf.ibid.The three terms a gub-ba,ká gu-la,and KÙ.AN also occur in sequence at the beginning of AAICAB 1/3,Bod.S 168,which lists two slaughtered sheep for the a gub-ba,and one each for the ká gu-la and the KÙ.AN.13Following this group are the three deceased kings of Ur–ulgi,Amar-Suen,and u-Suen,each of whom received a slaughtered sheep.

The remaining two shorter lists,Cohen 1993,181 RBC 2540 and AAICAB 1/3,Bod.S 225,correspond partly to the offerings in the two long lists discussed above.They record respectively one goat and one slaughtered sheep for the KÙ.AN.The first of the two,Cohen 1993,181 RBC 2540,summarized as níg-diri ezem-ma,“additional provisions for the festival,”records nine sheep and goats for various purposes.14The list includes the same kinds of offerings attested in the two long lists,except for one sheep and one goat described as gú-NE,and one sheep for the lustration water/rite? of the god Ninebgal.The second list,AAICAB 1/3,Bod.S 225,enumerates slaughtered sheep for the a gub-ba,the ká gu-la,and the ésir gir-ra gar.15The phrase ésir gir-ra gar possibly means“putting bitumen in a kiln.”Cf.the Old Akkadian text from Girsu,ITT 1,1451 Obv.1–2:50 ésir hád gur-sag-gál/ gir-ra gá-gá-dè;the Ur III Umma text NYPL 324 ( 48) Obv.1–2:1 (gur) 5 (bán) 7 sìla ésir É.A gur-lugal/ gir-ra ba-a-gar.The last occurrence makes it clear that gir-ra is in the locative case,so gir is presumably the same as Akkadian kīrum,a kiln (for lime and bitumen);see CAD K,s.v.“kīru,”415.The expression ésir (hád/É.A) girra gar appears to mean“to put (dry/wet) bitumen in a kiln.”Note courtesy of Gianni Marchesi.

The entitlement of the KÙ.AN to animal offerings and its connection with temple locations or ceremonies that took place in temples suggest that the KÙ.AN was a location or space in the precinct of a temple.This interpretation finds support in the record Orient 17,75 107 (S 7 ix),which mentions a door of the KÙ.AN and lists a number of copper items for it.Another text,BPOA 6,1363 (42/AS 6 vi),allocated two ox hides,one mina of dye or paint,16Sumerian še-gín,equivalent to Akkadian šimtu (Salonen 1965,202).and six workdays for the door of a KÙ.AN.These examples reveal that KÙ.AN not only means“treasure,”but also denotes more precisely a building where treasures were kept,that is,“a treasury.”The attestation of é KÙ.AN in UTI 3,1744(S 2) (quoted at end of §2.1),implies that KÙ.AN might have represented an abbreviation of that complete expression.17The same text also mentions a door for the treasury building (ig é KÙ.AN).

2.KÙ.AN in Connection with Metal Objects

2.1 As deliveries for ara

The term KÙ.AN is also attested in connection with metal objects,especially precious artifacts made of silver and gold.A group of three texts–UTI 5,3488(S 1),UTI 4,2566 (S 2 iv),and BIN 5,2 (S 4 iv)–features a long list of metal items that the Umma governor Ayakalla received from a certain Lugal-nir.The texts label the items in question as KÙ.AN ku4-ra,“brought into the treasury.”

Obv.

18 The term géšbaba means“wrestler”or“fist”(Sallaberger 1993,vol.I,178,n.838;257,n.1210).Inthe contextof thetextsstudiedinthepresentarticle,however,thistermappearsin thefollowing f ormula:weight +kù+géšbaba,wheretheaforementionedmeaningdoesnotfit.Heregéšbaba may qualifythe precedingword kùand referto a particular typeof silver.19ForÁB.À.GI,seeBalke 2015,10–13.He proposedto read it as gir9gi,inwhichgiserves as a phonetic complement.TheSumerian gir9refers toa big jar for storageand is borrowed intoAkkadian as kirrum.

20 Equivalent to Akkadian sikkūru.The Akkadian term means a door bolt made of wood,occasionally of silver and gold as well;see CAD S,s.v.“sikkūru,”256–259.Here it may refer to a decorative element of the goblet.21 Hallo (1963,137) suggests that it may be connected to alal,which means“pipe,water-carrier.”Examples collected by Limet (1960,199) show it was made of gold,bronze,and copper in addition to silver;cf.PSD 1 A/1,s.v.“a-lá,”103.Schrakamp (2010,135) provides an overview of the various meanings proposed for this term.According to him,a-lá can appear with or without sag-è,and carries the same meaning (i.e.,an area on the wooden shaft of a spear,lance,or an ax for fixing the blade).

The predecessor of governor Ayakalla,governor Ur-Lisi,also took precious items from Lugal-nir in the year of AS 8.23The items are labeled as deliveries for ara in seven months.The verbal form in UTI 6,3705 (AS 8)Rev.6 might be restored as [KÙ.AN-ka ba]-an-ku4,in light of the parallel in MVN 16,1554 ( 45)Obv.5.The photos (courtesy of the Istanbul Archaeological Museum) show that in the broken line,the signs before the last two have all been lost.Table 1 summarizes the four records altogether.

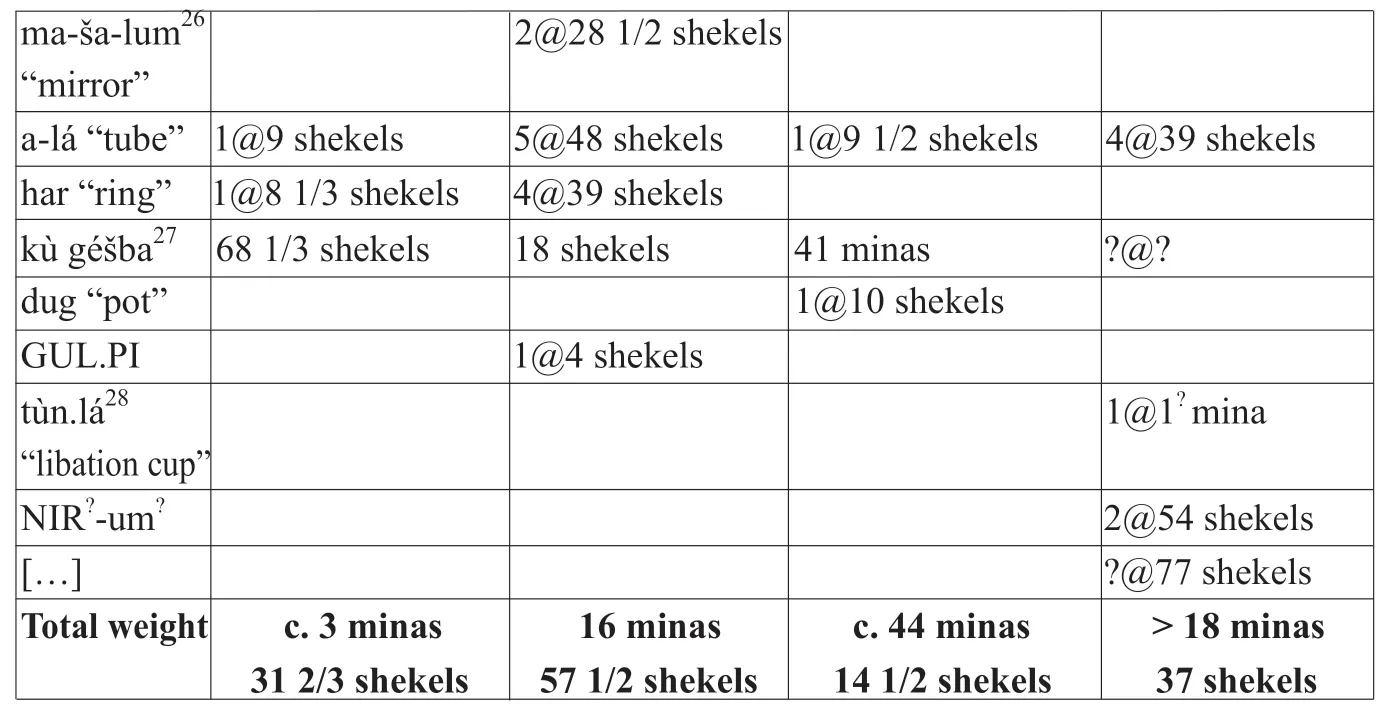

Table 1 :Governor’s withdrawals of silver objects described as KÙ.AN ku4-ra from Lugal-nir

26 Forasurveyofmirrors intheancientNear East,seeNemet-Nejat1993.Note:*Italsolistsitemsmadeofcopper,bronze,or stone.27 This term is only partially preserved in BIN 5,2 (S 4 iv) 17:kù U.┌BÙLUG┐[ba];and in UTI 6,3705 (AS 8) Obv.7:┌kù┐ U.[BÙLUG]ba.28 This kind of cup could be made of gold,silver,copper,or bronze (Paoletti 2012,150).

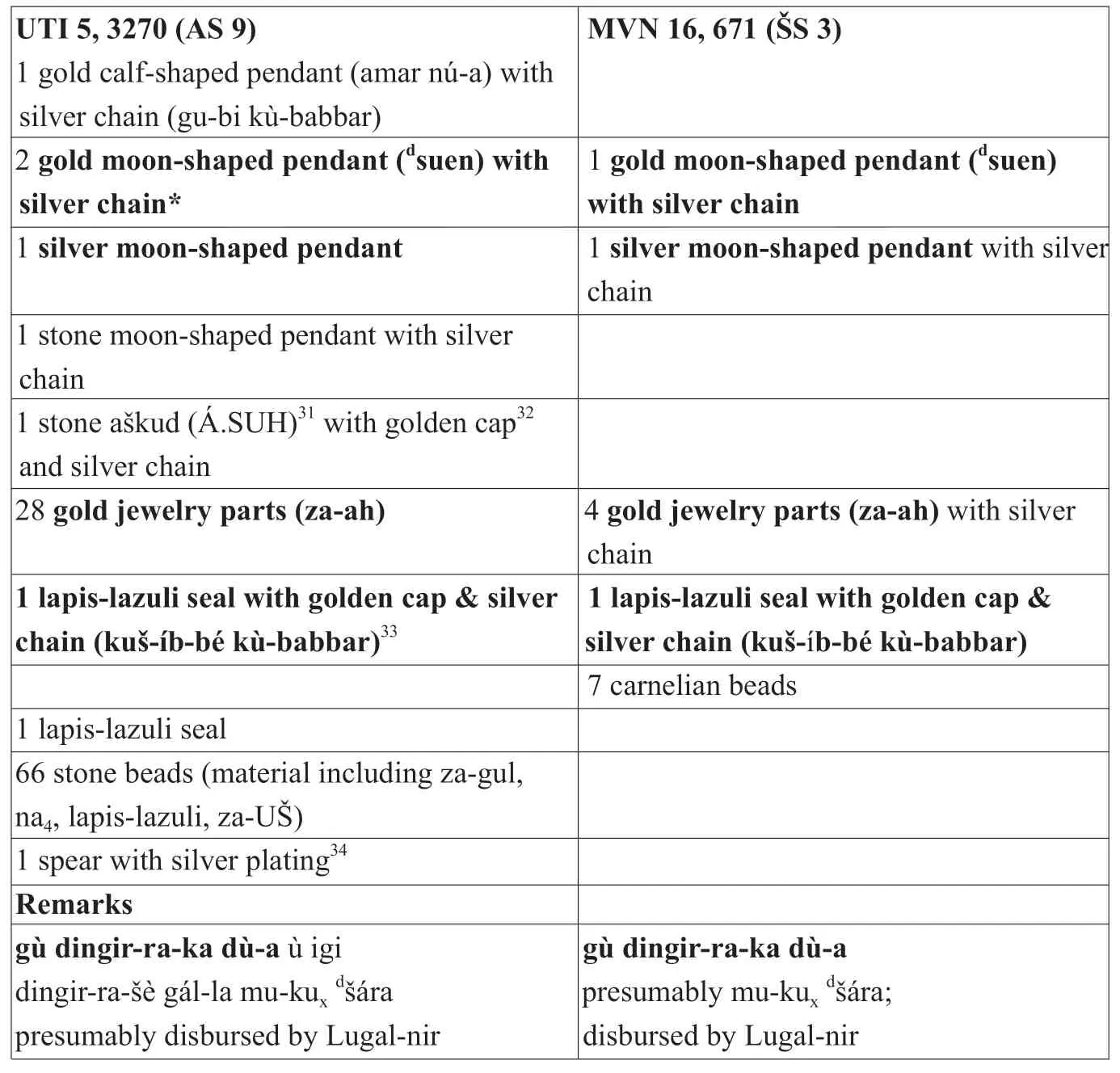

The lists summarized in Table 1 indicate that Lugal-nir was likely to be in charge of the treasury ofara.Therefore,in cases where the term KÙ.AN does not appear,one can assume that the disbursements made by Lugal-nir came from the same treasury as well.Not only did he disburse valuables from the treasury ofara to the governor,but also took responsibility for their daily use (Table 2 below).According to the text MVN 16,671 (S 3),Lugal-nir issued ornaments made of gold,silver,and precious stones for“decorating the neck of the god(i.e.,ara).”Similarly,the parallel record UTI 5,3270 (AS 9) lists precious items expended by Lugal-nir for“decoratingara’s neck”and for“being displayed before his eyes.”In yet another text MVN 16,1156 (S 2),the oil presserarazida sealed on his receipt of a silver basin (níg-luh) from Lugal-nir,which weighs four minas twenty-five shekels.29One may infer from his occupation that the oil presser withdrew this utensil to hold oil for sacred purposes and would likely return it to the treasury of ara thereafter.The precious items in these three records had all been intended as deliveries for the godara.In yet another case,as much as sixty minas of copper were said to come from Lugal-nir as well.30AAICAB 1/1,1911-483 (S 6 x) Obv.6–8:1 gú uruda/ 2 1/3 ma-na su-gan/ ki lugal-nir-ta.

Table 2 :Valuables disbursed by Lugal-nir for decorating divine statues

Table 3 :UTI 5,3407:Withdrawals of precious items marked as KÙ.AN-ka ku4-ra from akuge

Table 3 :UTI 5,3407:Withdrawals of precious items marked as KÙ.AN-ka ku4-ra from akuge

38 For a-gàr as a variant of a-gar5,see PSD 1 A/1,s.v.“a-gar5,”82.39 Translation follows Civil (1994,150).

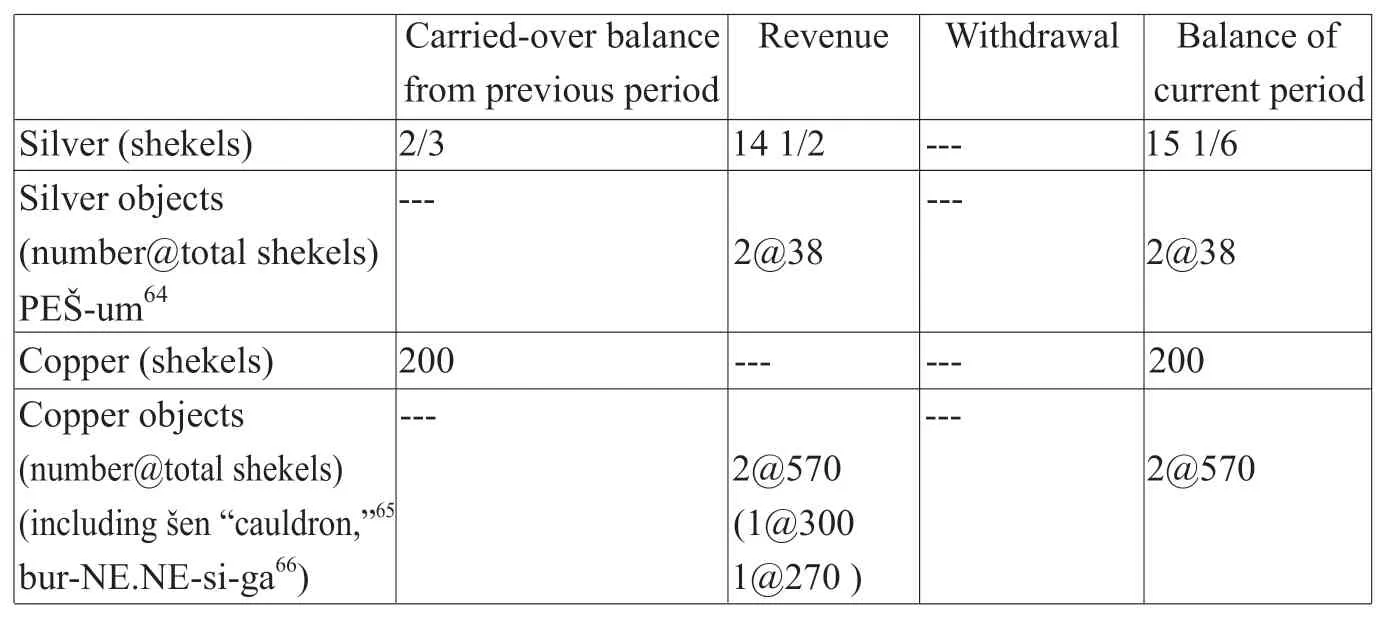

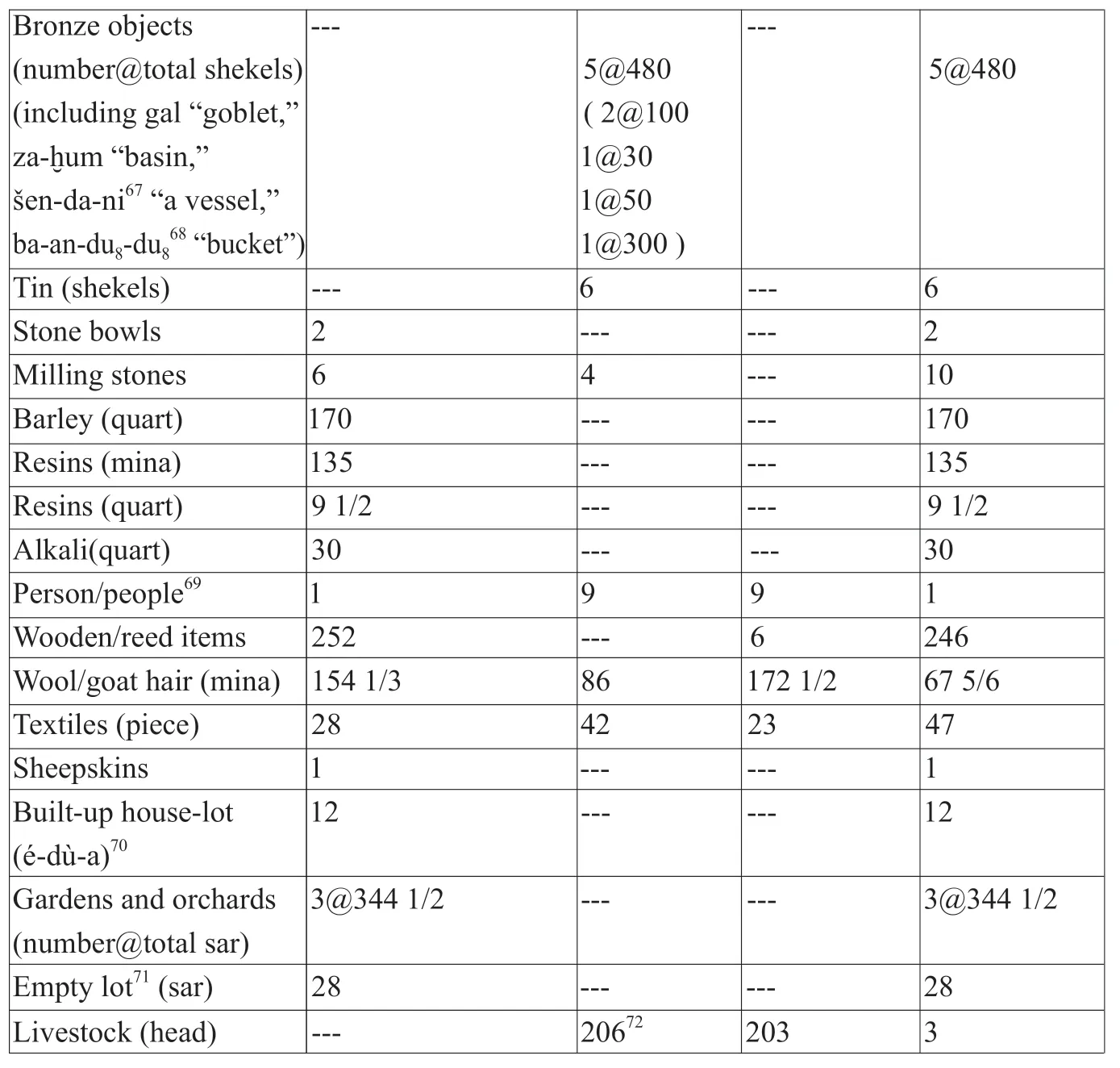

Table 4 :Summary of RA 86,97–103 1,balanced account on deliveries for ara of Apisal63

Table 4 :Summary of RA 86,97–103 1,balanced account on deliveries for ara of Apisal63

63 Table based on Lafont 1992,106–107.64 Name of a container,which could also be made of bronze (ibid.,99).65 Steinkeller (1981) studies the EN sign,which sometimes is confused with the ALAL sign.66 According to Lafont 1992,99,the writing of bur-izi (NE) stands for bur-zi,a kind of bowl.

Lugal-nir’s repeated expenditures of large quantities of valuables delivered forara suggest that he might have served as the custodian of the treasury of this god.Further evidence corroborates this hypothesis.On two other occasions,he received a wooden door for the treasury of an unnamed god (ig é KÙ.AN)35UTI 3,1744 (S 2),from Obv.5 on:1 gišig/ kuš gu4-bi 2-àm/ á-bi u4-5-kam/ ig é KÙ.AN/ ki a-akal-la šakkan6-ta/ kišib lugal-nir/ mu má den-ki ba-an-du8;seal lugal-nir/ dub-[sar]/ dumu ur-[dšára]/ GÁ-dub-ba-[ka].“One door,(which required) two ox-hides and five days of labor;door for the treasury,from Ayakala,the general;seal of Lugal-nir;the year when the boat of Enki was caulked;sealed by Lugal-nir,the scribe,son of Ur-ara,the archivist.”and twenty sheep-or goat-skins to pack the valuables designated as deliveries forara (kù mu-kuxdšára kéš-e-dè).36MVN 16 0844 (S 6) Obv.:20 kuš máš sila4/ kù mu-kux dšára kéš-e-dè/ ki a-a-kal-la ašgab-ta/kišib lugal-nir Rev.:mu na-rú-a mah ba-dù;seal lugal-┌nir┐/ dub-sar/ dumu ur-dšára/ GÁ-dub-ba-[ka].“Twenty skins of kids and lambs,in order to tie metal objects delivered for ara,from Ayakalla,the leather worker;seal of Lugal-nir;year when the great stele was erected;sealed by Lugal-nir,the scribe,son of Ur-ara,the archivist.”Both texts identify Lugal-nir as a scribe and a son of the well-known archivist Ur-ara.37See Ouyang 2013,45–98 for the role of Ur-dara in collecting silver payments in Umma.

2.2 As deliveries for avatars of ara

In addition to the fancy items,akuge dealt with objects of practical use.According to the text UTI 3,1780 (AS 8),he once disbursed two neck and nose rings made of bronze,weighing two minas in total,to a herdsman named Ur-Dumuzida.44Note that the rings had come from a delivery for the god ara.According to MVN 20,41 (AS 1),the same herdsman withdrew a bronze ring weighing 5/6 mina for a donkey to use;this ring had been a delivery for ara of the Umma city.

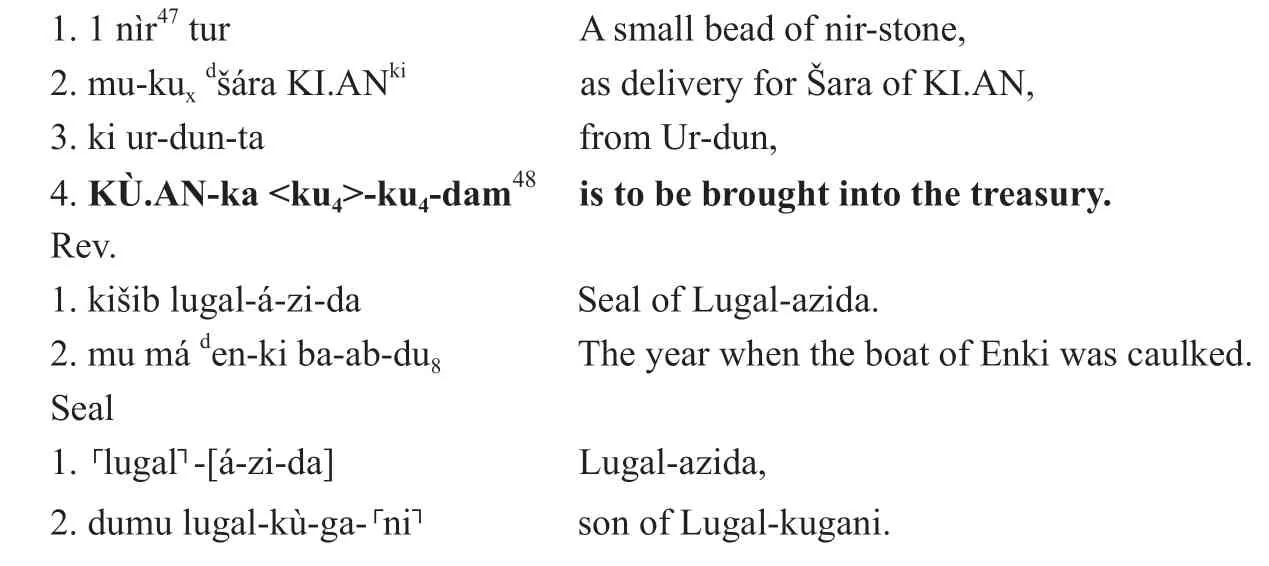

An expression involving KÙ.AN and the verb ku4,KÙ.AN-ka ku4-dam,appears for the first time in a record of Lugal-azida as follows:

Obv.

47 A study of the orthography of the stone name is available in Loding 1974,76–79;Veldhuis (2004,137) comments briefly on its orthography and white color.48 Following Thompsen (1984,265–268),Edzard (2006,132),and Jagersma (2010,655–662),the author analyzes the verbal phrase as/ku4+ed+am/,where/ku4/ stands for the hamu form of the verb,/-ed/ the morpheme denoting an imperfective participle or future action,and/-am/ the enclitic copula.However,as/-ed/ marks a mar participle,the mar base ku4-ku4 is expected instead of the hamu base ku4.The reading of ku4-dam is verified based on photos kindly provided by the Istanbul Archaeological Museum.As far as the author is aware of,this ku4-dam seems to appear elsewhere outside the Umma corpus only in the Puzriš-Dagan text MVN 5,106 ( 47 xi).The expected form,ku4-ku4-dam,appears in a handful of other records:ITT 3,5576 (AS 7),ITT 2,4123 (S 9 i),and KM 89265 (date uncertain)from Girsu;DIA 19.024.27 ( 44 xi) and MVN 15,180 ( 46) from Puzriš-Dagan;UET 3,57+UET 9,1177 (date lost) from Ur;and the text without provenience SAKF 108 ( 45).The sign KWU636 renders ku4 in UET 3,57+UET 9,1177 and ITT 2,4123,while KWU147 in the remaining texts.

According to this record,Lugal-azida,identified above as a priest,received a bead of precious stone,after which this bead should have gone to the treasury of the god.The occurrence here of theparticiple marker -dam,instead of theparticiple marker -a,may provide the key to distinguishing between the receipts and disbursements of a treasury custodian.The relatively low value of the single bead of the nir-stone further indicates that Lugal-azida received it from Ur-dun as a delivery forara of KI.AN.The large quantities dispensed by Lugalnir andakuge,as discussed above,represent items withdrawn respectively from the treasuries of the godara and that ofara of Apisal.In other words,the perfect or imperfect aspect of the verb ku4indicates the nature of the transactions conducted by the custodian of a temple treasury.

Additional records attest to Lugal-azida as a recipient of precious items meant to be deliveries forara of KI.AN.In the text MVN 9,171 (44),Lugal-azida took in deliveries from a number of individuals,each of whom contributed with one or two items as follows:

The overseer Galgalla–1 silver tube (a-lá) weighing 10 shekels,1 muš-uš emblem

Ur-Lugalbanda–1 copper cauldron (šen),1 bronze basin (za-um)

The doctor Dada–1 copper cauldron,1 bronze goblet (gal)

In the case of each contributor,the items that they supplied precede their names.In the records BPOA 6,911 (48) and BPOA 6,1177 (AS 2),Lugal-azida received from Dada,the namesake of the doctor above,two batches of valuables.50The earlier batch included a silver tube of ten shekels,a silver jar (ÁB.À.GI) of one mina,one mina of silver,and a copper item of ten minas;the later batch included a silver jar (ÁB.À.GI) of 2/3 mina,a silver boat model of ten shekels,and a copper goblet of 1/3 mina,all of which are marked as bar-ta gál-la (discussed below).

Ambiguities arise regarding the exact nature of deliveries to a deity.They do not represent a tax obligation imposed by the government,because the indicators of such an obligation (e.g.,lá-ìa [su-ga],“[repaid] arrears”)51E.g.,Ouyang 2013,38–40 with earlier literature.are never attested in the context of such deliveries.

Lafont suggests that a delivery labeled as mu-kuxof the god so-and-so,based on the instances where it appears together with the term a-ru-a,52Lafont 1992,101–102.may refer to some kind of ex-voto gift or donation.53The study of Gelb (1972) remains an essential reference to this phenomenon.Considering Lafont’s suggestion and the relatively low value of the bead recorded in the receipt discussed above,MVN 16,1468,the text might well have recorded such an ex-voto gift from Ur-dun for the godara of KI.AN.Sallaberger,however,points out that the phrase a-ru-a does not follow all the entries summarized as deliveries for a deity,54Sallaberger 1994,542–543.which thus undermines Lafont’s point.Sallaberger proposes instead that the deliveries of livestock designated for the emblems (written as x šu-nir,udu-bi y,with x and y standing for numbers) might have represented the payments made to a temple for taking an emblem out for service as a cultic object,which could emanate the power of a god.55Ibid.

Parallel evidence from the royal archives in Puzriš-Dagan,nonetheless,supports the hypothesis that the people involved donated the valuables toara as ex-voto gifts56Paoletti 2012,227–263.(i.e.Lafont’s point).In the shoe and treasure archives from Puzriš-Dagan,twenty-three tablets record disbursements of the king’s gifts to various deities in Ur (e.g.,Nanna,Anunītum),Uruk (e.g.Inanna,Gula),and Nippur (e.g.Enlil,Ninlil,Ninurta).The texts note such gift-giving as a-ru-a lugal without the Sumerian term mu-kuxfor“delivery.”In addition,dozens of entries recording such donations can be further recognized in other records of expenditure.The donations feature vessels,utensils,jewelry,and other objects made of precious metals with decorations of precious stones.The donations took place on the occasion of the Akītu festivals in Ur,the Tummal festival in Nippur,the monthly festivals,and the lustration rites (a-tu5-a),or on other unspecified occasions.

2.3 As deliveries for other deities

3.KÙ.AN in Connection with Artisans

In the record SNAT 359 (AS 5 viii),a blacksmith calledalulu received a copper cauldron (šen) of nine minas fifty shekels described as KÙ.AN-ta è-a,“coming out of the treasury.”alulu appears again in the text PPAC 4,218 (no date),perhaps a memorandum tag,which summarizes his copper transactions as KÙ.AN-ta è-a.Thisalulu functioned as a specialist involved in the weighing of bronze and copper objects in Umma.60D’agostino and Gorello 2013,251–265,esp.257–258.The expression KÙ.AN-ta è-a spells out disbursements from the treasury in question.

4.Administration of the KÙ.AN

The discussions above show that the valuable items in the treasury of a god came from the deliveries to the same deity.Evidence elsewhere points out,however,that objects of precious metals and stones accounted for a mere part of a deity’s deliveries,which featured consumables and real estate as well.The text RA 86,97–103 1 (AS 7) presents a balanced account on deliveries to and withdrawals from the temple ofara of Apisal during one year61This account also includes several pieces of textiles as deliveries for the deified king Maništušu(Obv.iii:24–26) from the previous Old Akkadian dynasty.Perhaps this temple of ara had a chapel dedicated to Maništušu according to Lafont 1992,101.and thus offers a glimpse into the broad spectrum of goods delivered for a god.akuge,the išib-priest identified above,appears as the person in charge of this account.

The deliveries in this account included objects made of silver,copper,and bronze,small amounts of silver and tin,stone bowls,milling stones,resins,alkali,people,animal byproducts (skins,wool,hair),items of reeds and wood,and real estate (gardens,orchards,house-lots).62The house-lots and orchards were the two forms of real estate that could be privately owned and freely alienated at Ur III times.In contrast,arable land could not be transacted during this period(Steinkeller 1989,127–128).

67 Perhaps a spouted vessel for holding oil (Limet 1960,227).68 Equivalent to Akkadian banduddm.69 Including male children (dumu-níta),female children (dumu-mí),and women workers (géme).70 A discussion about this term in sale documents appears in Steinkeller (1989,122–123).The examples collected there feature the metrological unit of surface,sar,but this unit is not mentioned in the balanced account here (Obv.i:14).71 Written as KI.UD,probably read as kislah.It means“empty,unoccupied ground (of house lots and orchards”(Steinkeller 1989,123–125).When it appears in conjunction with houses or orchards,it refers to empty ground next to the house or uncultivated land accordingly.72 Including sheep for emblems (šu-nir),wooden lances (gišgíd-da),and dumu kar-ra (Lafont 1992,100–101).The dumu kar-ra may refer to young children dedicated to a temple as oblates by their parents as in this text,or illegitimate children born out of marriage in other sources (ibid.,101,n.12).Sallaberger (1994,543) disagrees and proposes instead the meaning of“children taken away from the temple (by the people aforementioned).”The author is not convinced by Sallaberger’s proposal and leans toward the opinion of Lafont.A search in BDTNS and CDLI shows that this term is attested only in Umma and often associated with one sheep and one piece of textile.

The frequent association of the KÙ.AN with valuables of precious metals and stones delivered for the Umma gods contrasts with the greater varieties of deliveries for the same gods documented elsewhere (such as the balanced account above).The contrast suggests an intended effort to separate the valuable items from other kinds of deliveries and to deposit them in the treasury of a temple called KÙ.AN.Umma’s patron godara,as well as his local avatars in Apisal and KI.AN,boasted the best-attested temple treasuries in Umma.The lesser deity Nin-duluma had a treasury as well.The deliveries forara surpassed those for other deities in both quantity and value.

Each temple treasury had one custodian,who could be a scribe,as in the case of Lugal-nir,or a priest,as in the cases ofakuge (išib) and Lugal-azida(gudu4).Perhaps for security reasons,the custodian of a treasury showed a special concern for its door.Both Lugal-nir andakuge withdrew a door or door decorations from their fellow administrators.They received deliveries of precious items by individuals,and then dispensed a large quantity of them to the incumbent governor of the province and the head administrator of the Apisal district respectively.The governor Ayakalla (in office AS 8-S 7 ii),for example,withdrew silver items weighing tens of minas from the treasury ofara in the years ofS 1,2 (month iv),and 4 (month iv).His withdrawals featured utensils,vessels,and jewelry items,and he rolled his seal on the tablets recording these withdrawals.The texts remain silent concerning the use of his withdrawals.Considering,however,that month iv was the most important month on Umma’s ritual calendar,the governor might have withdrawn these items to perform rituals in worship of the godara.The texts do not disclose whether or not the governor returned his withdrawals to the god’s treasury.One may speculate that the governor might not have returned his withdrawals after using them,as the contents and quantity of his withdrawals varied from year to year.

The precious objects brought into and out of the KÙ.AN in Umma remind us of the valuable items“stored in the sacristies/cupboards ([giš]gú-ne-sag-gá) of various temples and shrines at Iri-Sagrig/Āl-arrākī and its nearby towns.”73Owen 2013,29.The items were likewise made of metal,stone,and wood,and listed in the inventory records in the charge of gudu4-priests.Most of them may have been acquired as“votive offerings or as gifts from the king,governors,and other notables.”74Ibid.,31.They either served in the rituals involving food and drinks,or decorated ceremonial spaces and divine statues.75Ibid.

In a nutshell,the study of KÙ.AN attested in the administrative records pinpoints its meaning as“treasury”and provides a glimpse into how the major temple households in Ur III Umma managed their treasures.Evidence indicates that buildings were set up as treasuries in the temples,in order to take special care of their valuables (which may have been donated as personal gifts for the gods) and keep track of them apart from other kinds of donations such as livestock and real estate.The precious items served primarily in the worship of gods,and,to a lesser extent,in the activities of production.

Appendix

Notes:* BDTNS follows Cohen (1993,181) in the date of the text,while CDLI provides no date for this text.Cf.note 4 in article.** Month provided in CDLI,but not in BDTNS.*** Parallel in the same text:Obv.7 mu giš┌ig┐gká é šen-al-lu5-ka-šè.

Bibliography

Balke,T.E.2015.

Civil,M.1983.

“The Sign LAK 384.”Orientalia Nova Series52:233–240.

—— 1994.

The Farmer’s Instructions.Barcelona:Editorial AUSA.

Cohen,M.E.1993.

The Cultic Calendars of the Ancient Near East.Bethesda,MD:CDL.

D’Agostino,F.and Gorello,F.2013.

“The Control of Copper and Bronze Objects.”In:S.J.Garfinkle and M.Molina(eds.),From the 21st Century B.C.to the 21st Century A.D.:Proceedings of the International Conference on Sumerian Studies Held in Madrid 22–24 July 2010.Winona Lake,IN:Eisenbrauns,251–265.

Dahl,J.L.2007.

The Ruling Family of Ur III Umma:A Prosopographical Analysis of an Elite Family in Southern Iraq 4000 Years Ago.Leiden:Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten.

Desset,F.2018.“Nine Linear Elamite Texts Inscribed on Silver ‘Gunagi’ Vessels (X,Y,Z,F’,H’,I’,J’,K’ and L’):New Data on Linear Elamite Writing and the History of the Sukkalmah Dynasty.”Iran56:105–143.

Edzard,D.O.2006.

Sumerian Grammar.Atlanta:Society of Biblical Literature.

Gelb,I.J.1972.

“The arua Institution.”Revue d’Assyriologie et d’Archéologie Orientale66:1–32.

Hallo,W.W.1963.

“Review of Limet 1960.”Bibliotheca Orientalis20:136–141.

Jagersma,B.2010.

A Descriptive Grammar of Sumerian.PhD-dissertation:Leiden University.

Lafont,B.1992.

“Quelques nouvelles tablettes dans les collections américaines.”Revue d’Assyriologie et d’Archéologie Orientale86:97–111.

Limet,H.1960.

Le travail du métal au pays de Sumer au temps de la IIIe dynastie d’Ur.Paris:Société d’Édition Les Belles Lettres.

Loding,D.M.1974.

A Craft Archive from Ur.PhD-dissertation:University of Pennsylvania.

Nemet-Nejat,K.R.1993.

“A Mirror Belonging to the Lady-of-Uruk.”In:M.E.Cohen,D.C.Snell and D.B.Weisberg (eds.),The Tablet and the Scroll:Near Eastern Studies in Honor of W.W.Hallo.Bethesda,MD:CDL,163–169.

Ouyang,Xiaoli.2013.

Monetary Role of Silver and Its Administration in Mesopotamia during the Ur III Period (c.2112–2004 BCE):A Case Study of the Umma Province.Madrid:Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas.

Owen,D.I.2013.

“‘Treasures of the Sacristy’.”Revue d’Assyriologie et d’Archéologie Orientale107:29–42.

Paoletti,P.2012.

Der König und sein Kreis:Das staatliche Schatzarchiv der III.Dynastie von Ur.Madrid:Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas.

—— 2013.

“The Manufacture of a Statue of Nanaja:Mesopotamian Jewellery-Making Techniques at the End of the Third Millennium B.C.”In:S.J.Garfinkle and M.Molina (eds.),From the 21st Century B.C.to the 21st Century A.D.:Proceedings of the International Conference on Sumerian Studies Held in Madrid 22–24 July 2010.Winona Lake,ID:Eisenbrauns,333–345.

Renger,J.1969.

“Untersuchungen zum Priestertum der altbabylonischen Zeit:2.Teil.”Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie59:104–230.

Sallaberger,W.1993.

Der kultische Kalender der Ur III-Zeit.Berlin:Walter de Gruyter.

—— 1994.

“Review of Catalogue of Cuneiform Tablets in Birmingham City Museum 2:Neo-Sumerian Texts from Umma and Other Sites,by P.Watson,with Some Copies by W.B.Horowitz.”Orientalische Literaturzeitung89:538–545.

—— 1995.

“Review of Sigrist 1992.”Bibliotheca Orientalis52:440–446.

Salonen,A.1965.

Die Hausgeräte der alten Mesopotamier:Nach sumerisch-akkadischen Quellen.Helsinki:Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia.

Schrakamp,I.2010.

Krieger und Waffen im frühen Mesopotamien:Organisation und Bewaffnung des Militär in frühdynastischer und sargonischer Zeit.PhD-dissertation:Fremdsprachliche Philologien,Philipps-Universität Marburg.

Sigrist,M.1992.

Drehem.Bethesda,MD:CDL.

Steinkeller,P.1981.

“Studies in Third Millennium Paleography.2:SignsEN and ALAL.”Oriens Antiquus20:243–249.

—— 1989.

Sale Documents of the Ur-III-Period.Stuttgart:Franz Steiner Verlag.

—— 2002.

“Stars and Stripes in Ancient Mesopotamia:A Note on Two Decorative Elements of Babylonian Doors.”Iranica Antiqua37:359–371.

Stępień,M.1996.

Animal Husbandry in the Ancient Near East:A Prosopographic Study of Third-Millennium Umma.Bethesda,MD:CDL.

Thompsen,M.-L.1984.

The Sumerian Language:An Introduction to its History and Grammatical Structure.Copenhagen:Akademisk Forlag.

Veldhuis,N.2004.

Religion,Literature,and Scholarship:The Sumerian Composition“Nanše and the Birds.”Leiden &Boston:Brill &Styx.