Egg recognition in Cinereous Tits (Parus cinereus): eggshell spots matter

2020-01-11JianpingLiuCanchaoYangJiangpingYuHaitaoWangandWeiLiang

Jianping Liu, Canchao Yang, Jiangping Yu, Haitao Wangand Wei Liang*

Abstract

Keywords: Brood parasitism, Egg recognition, Egg rejection, Eggshell spots, Parus cinereus

Background

The mutual adaptations and counter-defense strategies between brood parasitic birds such as cuckoos (Cuculus spp.) and their hosts are comparable to an arms race for studying coevolution (Rothstein 1990; Davies 2000, 2015).Coevolutionary theory predicts that if brood parasitism is costly, hosts will evolve anti-parasite defense against brood parasitic birds, while brood parasitic birds will evolve parasitic strategies to crack their hosts’ defenses.To recognize and reject parasitic eggs is the most common and effective strategy among anti-brood parasite defense mechanisms (Davies 2000; Soler 2014), and the most common methods of hosts are therefore egg ejection and nest desertion (Šulc et al. 2019). In response to egg rejection by hosts, many parasitic birds evolve counter-adaptations to overcome the hosts’ defenses by laying mimicking (Brooke and Davies 1988; Avilés et al. 2006;Stoddard and Stevens 2010; Yang et al. 2010; Antonov et al. 2012; Abernathy et al. 2017; Meshcheryagina et al. 2018) or hidden eggs (Brooker and Brooker 1989;Brooker et al. 1990; Langmore et al. 2009; Gloag et al.2014). Currently, more than 60% of cuckoo species lay eggs that mimic one or many different host eggs (Johnsgard 1997; Payne 2005). Generally, parasitic eggs mimic the background color, spot size, spot color, spot distribution, and shapes of the host eggs (Avilés et al. 2006; Starling et al. 2006; Spottiswoode and Stevens 2010; Antonov et al. 2012; de la Colina et al. 2012; Honza et al. 2014;Stoddard et al. 2014; Abernathy et al. 2017; Attard et al.2017; Meshcheryagina et al. 2018). Egg mimicry makes it more challenging for hosts to detect the parasitic eggs(Cassey et al. 2008; Spottiswoode and Stevens 2010).And many hosts cannot recognize the parasitic egg, and are therefore forced to accept foreign eggs (Davies 2000;Langmore et al. 2003; Stokke et al. 2016).

Variable egg colors and spotting patterns are unique characteristics of birds (Hauber 2014). The spots are mainly composed of two pigments, protoporphyrin and biliverdin (Kennedy and Vevers 1976; Mikšík et al. 1996;Gorchein et al. 2009). There are many explanations for the role of the egg spots (Kilner 2006; Reynolds et al.2009; Maurer et al. 2011; Stokke et al. 2017).

The first explanation is that spots are used as a protective coloration. Newton (1896) believed that spots can help to conceal the eggs and reduce the risk of predation(Kilner 2006; Hanley et al. 2013; Duval et al. 2016).

The second explanation is related to signal function for sexual selection. Some studies have shown that the pigments from the spots can imply the quality of the female or chick as well as the willingness of the female to reproduce, which affects male parental investment (Sanz and García-Navas 2009; López-de-Hierro and De Neve 2010;Stoddard and Stevens 2011; Stoddard et al. 2012; Hargitai et al. 2016; Poláček et al. 2017).

The third explanation is associated with structural function as egg spots can improve eggshell strength(Gosler et al. 2005; García-Navas et al. 2010; Bulla et al.2012; Hargitai et al. 2013, 2016).

The fourth explanation is related to brood parasitism.Swynnerton (1918) proposed that the spots can be used in defense against cuckoo parasitism. This signature hypothesis predicts that cuckoo hosts should evolve less variation within their own clutches (to make it easier to pick out a parasitic egg), and more variation between the clutches of different females within a species (to make it harder for cuckoos evolve to a good match) (Swynnerton 1918). Much previous work agreed with this theoretical prediction (Davies and Brooke 1989a, b; Soler and Møller 1996; Stokke et al. 2002, 2007; Takasu 2003; Stoddard and Stevens 2010; Medina et al. 2016).

In fact, in response to cuckoo egg mimicry, hosts have evolved egg spotting patterns that can work as a unique“signature” for the female host (Davies 2000; Spottiswoode and Stevens 2010; Stoddard et al. 2014), which then makes it easier to detect foreign eggs (Swynnerton 1918; Stoddard and Stevens 2010; Davies 2011; Caves et al. 2015; Stokke et al. 2017). For example, the eggs of Tawny-flanked Prinia (Prinia subflava) have noticeable signatures, i.e., different egg color, egg spot size, egg shape, and distribution of egg spots, and they can accurately identify foreign eggs that are different from own eggs using these features (Spottiswoode and Stevens 2010). More recently, an experimental study showed that a frequent host of the parasitic Shiny Cowbird (Molothrus bonariensis), the Chalk-browed Mockingbirds(Mimus saturninus), rejected spotted eggs (32.4% of trials, n = 11 of 34 eggs) less than unspotted eggs (58.3%of trials, n = 21 of 36 eggs), irrespective of color (Hanley et al. 2019).

The Great Tit (Parus major) is a passerine bird in the tit family Paridae and is grouped together with numerous other subspecies. However, DNA studies have shown these other subspecies to be distinctive from the Great Tit, and have now been separated into two distinct species, the Cinereous Tit (Parus cinereus) of southern Asia,and the Japanese Tit (P. minor) of East Asia. The Great Tit remains the most widespread species in the genus Parus (Päckert et al. 2005). Recent studies have shown that coevolutionary interactions have existed between tits and cuckoos in China (Liang et al. 2016; Yang et al.2019). In China, the Cinereous Tit has evolved the ability to recognize eggs and the rejection of non-mimetic eggs by Cinereous Tits is from 54.1% up to 100% (Liang et al.2016). However, whether spots play a role in egg recognition has not been studied. The aims of our study were to further test the egg recognition ability of Cinereous Tits and to explore the role of eggshell spots in egg recognition in particular.

Methods

Study area

The study was carried out in Saihanba National Forest Park, Weichang, Hebei (42°02′-42°36′N,116°51′-117°39′E). It is the main natural secondary forest and plantation forest area in Hebei, with an altitude of 1500 m. It has a cold temperate continental monsoon climate (Liu et al. 2017). Zuojia Nature Reserve was in Jilin, northeastern China (44°1′-45°0′N, 126°0′-126°8′E).The mean altitude is 300 m, with a continental monsoon climate and four distinct seasons in the temperate zone.Vegetation is temperate needle broad-leaved mixed forest zone with secondary forest (Yu et al. 2017). We monitored Cinereous Tits nesting in nest boxes during the breeding seasons each year. The nest boxes were attached to trees about 3 m above the ground, facing in a random direction (Liang et al. 2016; Yu et al. 2017).

如何实现人体组织的修复或者再生一直以来都是医学领域的热门研究方向,口腔医学界也毫无例外。近年来,关于口腔组织的修复或再生无论在细胞实验、动物实验以及临床运用上都取得了令人惊喜的成果。1998年富血小板血浆(platelet-rich plasma,PRP)第一次从人的血液中被成功提取,由于PRP制备过程复杂,需要添加外来生物制剂,存在伦理学和免疫排斥,PRP的使用受到了限制[1]。

Egg experiment

Field experiments were carried out from April to August in 2018 and 2019. The pure white eggs (without spots) of White-rumped Munias (Lonchura striata) show the same color as the background of Cinereous Tit eggs (Fig. 1a).The eggs of White-rumped Munias (1.28 ± 0.12 g in egg mass, 16.20 ± 0.82 mm × 12.46 ± 0.68 mm in egg size,n = 15) are a bit smaller than the eggs of Cinereous Tits(1.42 ± 0.20 g in egg mass, 17.03 ± 0.72 mm × 13.00 ± 0.3 6 mm in egg size, n = 136). Except this, the only difference between White-rumped Munias and Cinereous Tit eggs was that munias eggs were without spots (Fig. 1a).We used professional marker (APM 25201, M&G) to speckle the eggs of White-rumped Munias to make them more similar to those of tits (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1 Brood parasitism experiments conducted in the nests of the Cinereous Tits (a seven Cinereous Tit eggs and one White-rumped Munia egg; b seven Cinereous Tit eggs and one White-rumped Munia speckled egg)

We checked the nest boxes regularly to determine the breeding status of the tits. One or two days after the clutch was completed, we experimentally parasitized nests by (1) adding one pure white eggs of White-rumped Munias (without spots) to the nests of Cinereous Tits; or(2) by adding one speckled White-rumped Munia eggs(with spots) to the nests of Cinereous Tits. The experimental nests were re-examined after 5 days. On the 6th day, if the experimental egg was still in the nest, and the host had not deserted, the experimental egg was considered accepted by the host. However, if the experimental egg had disappeared or was damaged (but not own eggs), it was considered rejected by the host. If the nests were preyed on or destroyed within the 6 days, they were excluded from the experiment (Liang et al. 2016). We did four experiments at these two sites, only experiment with white eggs in Zuojia was carried out in 2018 and the rest of experiments in 2019.

Data analysis and statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS 25.0 for Windows (IBM Inc., USA). Rejection rates of Whiterumped Munia eggs and speckled White-rumped Munia eggs were compared using Fisher’s exact test. All tests were two-tailed, with statistical significance at p < 0.05.The data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation(mean ± SD).

Results

Egg recognition

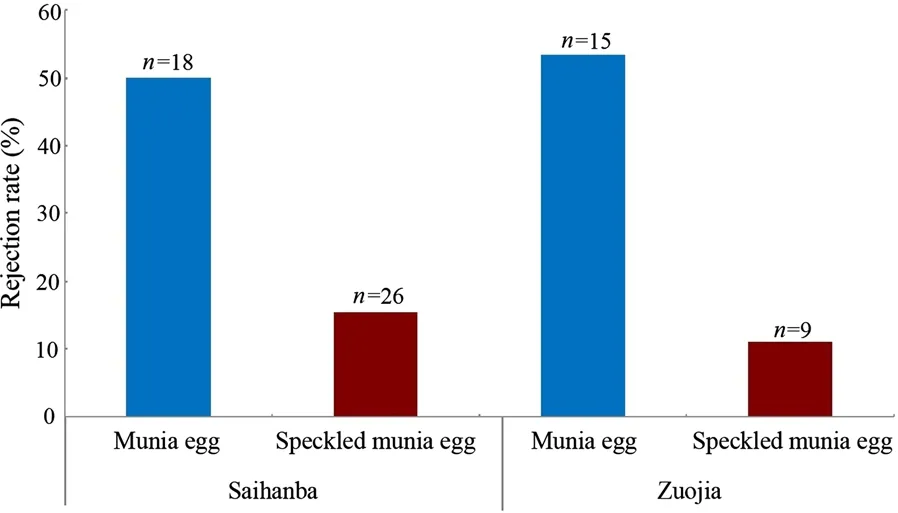

Fig. 2 Rejection frequency of foreign eggs in parasitism experiments by Cinereous Tits. Numbers on bars refer to sample size

In the Saihanba region in Hebei, the rejection rate of munia eggs and speckled munia eggs by Cinereous Tits was 50% (n = 18) and 15.4% (n = 26), respectively (Fig. 2).In the Zuojia Nature Reserve in Jilin, the rejection rate of munia eggs and speckled munia eggs by Cinereous Tits was 53.3% (n = 15) and 11.1% (n = 9) (Fig. 2). Cinereous tits from the two populations showed a high rejection of munia eggs and a low rejection of speckled munia eggs.And Cinereous Tits from the two populations showed no differences in their ability to recognize the two types of experimental eggs (Fisher’s exact test, all p > 0.05). Thus,these results were combined. Experimental parasitism results showed that the recognition rates of Whiterumped Munia eggs and speckled White-rumped Munia eggs by Cinereous Tits were 51.5% (n = 33) and 14.3%(n = 35), respectively. There was a significant difference in the recognition rate between the two egg types (Fisher’s exact test, χ2= 10.757, df= 1, p = 0.002).

Discussion

From the eye of human being, the pure white eggs of White-rumped Munia appeared similar to Cinereous Tit eggs in the background color. But our results indicated that Cinereous Tits have high recognition ability for White-rumped Munia eggs. It could be due to the fact that from the Cinereous Tit’s point of view there is still a difference in the background color between the eggs of the White-rumped Munia and the Cinereous Tit’s own eggs.For example, tits could perceive UV color that humans cannot see (Cuthill et al. 2000) and therefore they could potentially reject experimental eggs based on these UV signals (Šulc et al. 2016). It could also be that the eggs of White-rumped Munia lack spots compared with those of Cinereous Tits themselves. However, when we speckled the eggs of White-rumped Munias, the rejection rate of speckled munia eggs by Cinereous Tits was significantly lower than that of the non-speckled ones, which suggests that eggshell spots play an important role in egg recognition for Cinereous Tits. Swynnerton (1918) proposed that eggshell spots act as signatures, and are used as a brood parasitism defense strategy, mainly against cuckoo egg mimicry.Our results show that eggshell spots may play a key role in identifying and rejecting parasitic eggs for Cinereous Tits. Numerous studies have been undertaken on the role of egg spots in identifying foreign eggs, and several perspectives from these studies are summarized as follows:(1) egg spots do not contribute to egg recognition, and egg size is the main clue to identifying eggs (Mason and Rothstein 1986; Marchetti 2000; Langmore et al. 2003); (2)spot patterns and egg colors are more important than egg size for egg recognition (Rothstein 1978; Lawes and Kirkman 1996; Igic et al. 2015; Antonov et al. 2006); (3) both egg colors and spot patterns affect egg rejection behavior by the host, but the egg colors are more important than the spot patterns (Lahti and Lahti 2002; Spottiswoode and Stevens 2010; Luro et al. 2018); (4) egg spot patterns are more important than egg colors for egg recognition (Underwood and Sealy 2006; López-De-Hierro and Moreno-Rueda 2009; de la Colina et al. 2012; Šulc et al. 2016); and (5) spots on the blunt pole of the egg provide a cue for egg recognition (Lahti and Lahti 2002; Polačiková et al. 2007, 2010;Polačiková and Grim 2010). There were so many different signals influencing the host’s response. As bird eggs themselves contain many characteristics, e.g., the background color, spot size, spot color, spot distribution, shapes and sizes of the host eggs, hosts may use the most available cues in making rejection decision, or may integrate several different egg characteristics in making such decision(Rothstein 1982; Spottiswoode and Stevens 2010). For example, some birds breed in the darkness of the tree cavities or deep burrows where visual cues are limited, tactile sensations become sensitive and thus egg size may play an important role in egg recognition (Mason and Rothstein 1986). However, in general, our experiment clearly shows that egg spots may play a role in the egg recognition process of Cinereous Tit. Although our study found that egg spots of Cinereous Tits may be essential for identifying and rejecting foreign eggs, it was unclear how the egg spots were deciphered by the tits and this required further investigation.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that egg spots of Cinereous Tits are important clues for egg recognition. However, the specific characteristics of the spot patterns, such as spot distribution, spot size, spot brilliance, chroma, hue, and UV may also be potential clues for egg identification. We suggest that future studies should focus on which of these features determine egg recognition and egg rejection behavior in Cinereous Tits and other tit species.

Acknowledgements

Authors’ contributions

WL designed the study. JL, JY and HW carried out field experiments. CY performed statistical analyses. JL wrote the draft manuscript, and WL revised and improved the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(Nos. 31772453 and 31970427 to WL, No. 31672303 to CY and No. 31770419 to HW).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The experiments reported here comply with the current laws of China.Fieldwork was carried out under the permission from Saihanba National Forest Park, Hebei, and Zuojia Nature Reserve, Jilin, China. Experimental procedures were in agreement with the Animal Research Ethics Committee of Hainan Provincial Education Centre for Ecology and Environment, Hainan Normal University (Permit No. HNECEE-2011-001).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author details

1Ministry of Education Key Laboratory for Ecology of Tropical Islands, College of Life Sciences, Hainan Normal University, Haikou 571158, China.2Jilin Engineering Laboratory for Avian Ecology and Conservation Genetics, School of Life Sciences, Northeast Normal University, Changchun 130024, China.

3Ministry of Education Key Laboratory of Vegetation Ecology, School of Life Sciences, Northeast Normal University, Changchun 130024, China.4Jilin Provincial Key Laboratory of Animal Resource Conservation and Utilization,School of Life Sciences, Northeast Normal University, Changchun 130024,China.

Received: 25 July 2019 Accepted: 17 September 2019

猜你喜欢

杂志排行

Avian Research的其它文章

- Avian influenza virus surveillance in migratory birds in Egypt revealed a novel reassortant H6N2 subtype

- Optimal analysis conditions for sperm motility parameters with a CASA system in a passerine bird, Passer montanus

- The role of temperature as a driver of metabolic flexibility in the Red-billed Leiothrix (Leiothrix lutea)

- Differential cell stress responses to food availability by the nestlings of Asian Short-toed Lark (Calandrella cheleensis)

- Optimal diet strategy of a large‑bodied psittacine: food resource abundance and nutritional content enable facultative dietary specialization by the Military Macaw

- Exotic parrots breeding in urban tree cavities: nesting requirements, geographic distribution, and potential impacts on cavity nesting birds in southeast Florida