Winding Canal Flows Ancient Town Grows

2020-01-06

“The ancient piers, temples, pagodas, bridges, streets, shops, factories and kilns, as well as the bustling markets and peoples daily life along the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal are unveiled for us like the unfolding Along the River During the Qingming Festival,” said the scholars. The glistening Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal (hereinafter referred to as “the Grand Canal”), ceaselessly running through thousands of kilometers, has nurtured hundreds of millions of population and carried Chinese civilization as long as thousands of years. The Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal stands for the soul of Chinese nation and the lifeblood of national unity and prosperity. The culture of Tongzhou Section at its north end is the epitome of such soul and lifeblood.

Traveling in a picture, when the sky meets the earth.

On an ordinary day, traveling along the Lu River (the ancient name of the waterway between Tongzhou and Tianjin) of the Grand Canals Tongzhou Section and the Tonghui River, passing the Dongfu Bridge (Dongguan Bridge at the east end of Xinhua Street, Tongzhou) and the Beifu Bridge (at the north post outside the north gate of Tongzhou), one could enjoy a splendid view of grain transportation by water. Cargo ships gradually slow down, approaching the wharf, which I heard is an extraordinary one: an exclusive wharf for grain transport, which is specially used for the inspection of grain transported to imperial granaries in Beijing and Tongzhou, named Shiba (Stone Dam). There is another one nearby called Tuba (Earth Dam). During the annual grain transport period, important materials, such as grain, are firstly, transported to Daguanglou on the riverbank, which is also known as the Grain Inspection Tower. Officials of the Ministry of Revenue check the grain quality there. Later, around 30 thousand dan (around 1.8 million kilograms) are usually transported in one night to the capital by the Tonghui River, and 50 thousand dan (around 3 million kilograms) transported from the Tuba. In addition, in case of emergency, at the Shiba, there is also an open-air granary outside the temporary granary for grain storage. With such a large throughput, how many large-scale ships are needed to transport all those grain to the capital? Turning around, there are more than 150 ships of various sizes on the river: official ships, cargo ships, barges and passenger ships. Someone tells me that official ships are exclusive for Feng Yingliu, Head of the Department of Grain of the Ministry of Revenue, cargo ships are managed by the royal government, while barges and passenger ships are responsible for grain transportation. Moreover, numerous people with different professions also contribute to grain transportation: those who pole the boat, those who guide the boat, those who dredge, those who set up signs for warning the shallows or whirlpools, those who deliver grain or other goods cargoes by vehicles or animals, , those who carry the sedans for officials and rich businessmen, those who transport goods by cart or livestock, those who peddle food and supplies on the riverbank, those who make and repair tools by the riverside, residents and officials, yamen runners, intellectuals and more than 800 people from all walks of life. How prosperous the grain transportation is!

Academic and Food Cultures along the Thousand-Year-Old Canal

Getting off the boat and strolling along the two sides of the Grand Canal, it is a good choice to explore the historical sites and learn local customs and the culture of the canal area. As far as I know, people who live and work on the canal generation by generation as ship owners, dockworkers and boat trackers endow the life here with uniqueness. Tongzhou, the northern tip of the Grand Canal, is known as the famous grain transportation terminal, directly administrated by the Head of Imperial Granary in Ming and Qing Dynasties. With numerous merchants gathering here, Tongzhou becomes the transport hub and trade center of northern China, characterized by advanced economic development. Therefore, merchants and travelers of different ethnic groups and religions are willing to settle down along the river, jointly developing the canal culture.

There were five academies in total during the Ming and the Qing dynasties, namely Tonghui Academy, Yang Xingzhong Academy, Wendao Academy, Shuanghe Academy in Ming Dynasty and Lu River Academy in Qing Dynasty. These academies were closely related to the Grand Canal and were all located by the west side at its north end. Together with Tongzhou Confucius Temple and the Tongzhou Examination Hall, they became an indispensable part of the Grand Canal culture, especially the Lu River Academy, which played a considerably influential part in it. Due to the fame of Lu River High School, whenever one mentions Lu River Academy, many people would regard it as the predecessor of Lu River High School. In fact, they have nothing to do with each other. According to research, Tongzhou had another academy named after the Lu River, but they were two independent academies. The earliest one was established by the government: the grain department bought residential houses with 450 liang (22.5kg) of silver, , changed them to the academy, and recruited teachers. Later, because the grain department experienced loss, the Lu River Academy was secured, and the Academy had to close. Since then, the Lu River Academy had been suffering from financial problems. In the forty-sixth year of Emperor Qianlongs reign in Qing Dynasty (1781), the Lu River Academy was the largest one since its establishment, both in terms of the size of buildings and the number of students. Later, because there were too many students, the was Academy had to be expanded again. Then, the “Hongwen Society” was established and changed to Tongzhou Governmental Primary School in the twenty-ninth year of Emperor Guangxus reign during the Qing Dynasty (1903).

At the same time, the Grand Canal, running for thousands of years, leaves us rich intangible cultural heritage: dough figurine, windmill, Chinese herb-made monkey and other folk crafts in the Tongzhou Section of the Grand Canal, as well as folk arts such as Dragon Lantern in Huo County and canal songs.

The Ancient Canal – The Hub of Grain Transportation

Why is Tongzhou so prosperous? Lets look back in history.

The Lu River Canal opened in the Jin Dynasty was used by the Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties, serving as an important part of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal. It was named as the Bai River in Yuan, Bai Cao in Ming, and North Canal in Qing. Since the Jin Dynasty, Tongzhou has been the north end of the Beiguo Canal. Since the Yuan Dynasty, Tongzhou has been the northern end of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal – its strategic position as a grain transport hub is self-evident. However, its history can date back to the Qin and Han Dynasties. As early as the First Emperor of Qin unified China, to suffice food supply to officers and soldiers who guard the Great Wall, the imperial government sent many officials to collect food from prosperous counties offshore, such as Huang Chui and Lang Ya, and transport grain to the now Haihe River, Tianjin by cart or ships. Furthermore, the collected grain was transferred to the outside of Tongzhou City by ship along the Bei River, also known as the Bai River, (now the North Canal), then to the northern section of the Great Wall by cart. Evidently, the Tongzhou nowadays was already a by-water food transport hub 2000 years ago.

Emperor Wanyan Liang of the Jin Dynasty planned to build a new capital Yan Jing in the third year of Tiande Era. Therefore, a large number of grain and goods needed to be collected and transferred from the Huai River and the Yellow River area, which then would be transported along the old waterway of Yongji Canal to Dingzigu (now Tianjin), then along the Lu River (now the North Canal) to the east of Lu County (now Tongzhou). Finally, the grain would be transported by cart to the construction sites of capital – all these explain the meaning of “hub of grain transport”, and Lu County was then promoted to Tongzhou. In the first year of Emperor Wanyan Liangs reign in Zhenyuan Era, the capital construction was finished, and the Jin Dynasty moved its capital from the present Acheng in Heilongjiang Province to Yanjing, which was renamed Zhongdu: this is the origin of the old saying that Tongzhou comes before the capital.

In order to quickly and sufficiently transport products from the Yangtze River and the Huai river areas to the capital, the imperial government of the Yuan Dynasty built the Jizhou River and Huitong River successively, straightened the bend of the Grand Canal in the Sui and Tang Dynasties, cut off the bend of the river surrounding Luoyang from the west, and restored the Bai River, finally developing the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal. At the same time, to improve the transfer between Tongzhou, the north end of the Grand Canal (including Zhangjiawan) and the capital city, the imperial government of Yuan Dynasty built the Ba River (from Mazhuang, the north of Yongshun Town, Tongzhou to Guangxi gate, the east gate of the capital city – namely outside Dongzhimen today) and the Tonghui River (now from Zhangjiawan city in Tongzhou to Jishuitan Lake in the capital city) successively. A large amount of food was transported to Zhangjiawan in Tongzhou by the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal, and then transported into the capital by the Tonghui River and the Ba River.

In the fourth year of Emperor Yongles reign in the Ming Dynasty (1406), in preparation of moving the capital to Beijing, Emperor Yongle of the Ming Dynasty dispatched his ministers to Sichuan, Jiangxi, Huguang (now Hunan and Hubei), Zhejiang and Shanxi to collect woods and build a palace in Beijing. The large number of precious woods from the Yangtze River and the Huai river areas were transported along the rivers to the Grand Canal, and then to Zhangjiawan. Because the waterway of the Grand Canal from the north of Tongzhou to Zhangjiawan was too shallow to navigate ships, ships and rafts from the south could not directly arrive in Tongzhou but only in Zhangjiawan for wood storage. Therefore, there was a timber factory built by the Ministry of Works here to store the wood for royal construction, thus called “Royal Timber Factory.” The Royal Timber Factory village in Zhangjiawen today has its namesake. Later in the seventh year of Emperor Jiajings reign (1528), the governors endeavored to shut out all the dissensions, insisted and presided over the reconstruction of Tonghui River, shifting the river estuary from to the north of Zhangjiawen to the north of Tongzhou. At the same time, they improved the section between the north of Tongzhou and Zhangjiawen, allowing ships to navigate straight to the Tongzhou City, thus shortening the distance of land transport between Beijing and Tongzhou. Then, the Ministry of Works set up another royal timber factory on the west bank of the north Grand Canal in Tongzhou city. When a village developed there, it was also named the Royal Timber Factory and is still in use today.

Since the 1970s, ten imperial wood have been unearthed on both sides of the Grand Canal in the east of Tongzhou city or during the water governance, including Phoebe zhennan, lignum vitae, wenge, Erythrophleum fordii and acacia wood. They are pealed square timber, ranging from 7 to 12 meters in length and 45 to 70 centimeters in side length of the cross section. All of them are still tough and intact. According to a local villager, Dengy Yu and other elderly people from Haojiafu Village, Lucheng Town, in the 1960s, when fishing in the canal in the southeast of the village, they stood on an inclined imperial wood in the river to cast nets, now the wood is still there. Later in 1998, during the search of a sunken ship in the South Canal, they discovered an imperial wood near the north shore. Combing the above findings with the History of the Ming Dynasty which says that: “the flood flushed all the wood away from the Imperial Wood Factory”, one can accurately infer that there must be countless imperial wood at the bottom of the Grand Canal, to the east of Tongzhou City. Since the imperial wood is firm and heavy, while gaining weight in water, the flood did not take it far before it sunk into the bottom of the river and held by the silt.

In addition to the timber, a large number of other construction materials such as bricks and stones were also needed for the construction of the imperial buildings in Beijing. These materials were mostly manufactured and mined in the south, transported to Tongzhou for storage via the Grand Canal, and then transported to the construction sites of imperial buildings in Beijing by cart After the reconstruction of Tonghui River in the seventh year of the Emperor Jiaqings reign of the Qing Dynasty, the Brick Factory, set up by the Ministry of Works, as well as the Imperial Wood Factory were moved to the north of Tongzhou City. Golden bricks and bricks for construction were manufactured in two independent factories, but the former one was more widely known, which was located in now Xinjian Village, Yongshun Town. Today, not far from the southeast of Brick Factory Village, Liyuan Town, there is an old waterway of the Grand Canal dated back to the 13th year of Emperor Jiaqings reign of the Qing Dynasty (1808), where there is a wharf called the Middle Wharf, because there is a wharf upstream (outside the east entrance of Shangmatou Village, Zhangjiawan Town), and a big wharf downstream. Thus, all the timbers and bricks for the construction of imperial buildings in Beijing were transported to Tongzhou via the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal first, then to Beijing for use. The canal transportation culture in Tongzhou is rich in both material and immaterial aspects.

The ancient town of Zhangjiawan, with its profound historical and cultural heritage, is an important window of the canal culture. The relics of the ancient walls in Zhangjiawan are located at the wharf outside the south gate of Zhangjiawan, a waterway at the north end of the Grand Canal. All the tributary messengers from other states, merchants from the north and the south, and people from all walks of life transferred here. Nowadays, we can only feel the historical impression from the ruts on the Tongyun Bridge. During the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, the walls of Zhangjiawan, with a great military importance, were demolished by Japanese invaders to build forts, and only the ruins of the walls were left. The ruins, only 100 meters long, were preserved thanks to the building of the barn in Tongxian County in earlier years. Now, it is planned to build the Zhangjiawan Park for preserving the original style of the village, restoring the charm of ancient streets and villages, recreating the historical features of water lanes and tea stalls, displaying the characterized landscape of the water town, more importantly, reproducing the prosperity of the former canal transportation.

The Olympic Flame Carried on the Grand Canal

On the morning of July 8, 2008, the sixth day of the sixth lunar month, a large and elegant wooden boat was sitting on the black cushion on the bank of Tongzhou Grand Canal, painted in copper yellow with its bow and tail set with carven dragon and phoenix. Peaches and cakes were placed on the table in the bow, people offered incense to pray for the safe journey. In the sound of gongs and drums, “Anfu Ship” (safety and well-being) gradually slid into water. As the bow left the last supporting cushion, the boatman standing in the bow released a carp, which is a symbol of good luck. Then the “Anfu Ship” slowly sailed to the cruise docks nearby to meet the boats that carry grains.

This royal cruise was originated from the “Anfu Ship” during the Emperor Qianlongs reign of the Qing Dynasty, and was created to carry the Olympic torch to Beijing in 2008 via the Tongzhou Section of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal, running through 11 kilometers. The torchbearers are on the “Anfu Ship” and other two cargo ships for grain transportation. The original magnificent “Anfu Ship” was exclusive for Emperor Qianlong to travel to the south of the Yangtze River six times via the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal. Various pavilions and towers were set up on the ship, and a large sail painted with a dragon was hang above the center, 29 meters in length and 6 meters in width. All patterns on the windows were carved according to those on the doors and windows in the Forbidden City. Emperor Qianlongs south tour was unprecedentedly grandiose and luxurious, With 3600 workers and more than a thousand boats to tow the grand ship. Such a luxurious and tremendous fleet of ships connected to each other navigated on the canal with the sails almost covering the sky. How spectacular they were!

At this point, the replica of the ancient ship and two other cargo ships for grain transportation completed their special task— carrying the Olympic flame on the Grand Canal…

Eight Scenes of Tongzhou in Ancient Times, “Green Heart” of the City at the Present

After understanding the grain transportation culture and the carrying of the Olympic torch on this ancient canal, lets cast our eyes on the Tongzhou City.

I still remember that in September 2019, there was a wonderful light show along the Grand Canal in Tongzhou. The widest water curtain was set up on the North Canal Bridge to present the “Eight Scenes of Tongzhou”, which first appeared in The History of Tongzhou in Emperor Jiaqings reign of the Ming Dynasty (1594). “Eight Scenes of Tongzhou” refer to the Dipamkar Pagoda thrusting into the clouds (Gu Ta Ling Yun), the Bali bridge meeting the moon (Chang Qiao Ying Yue), the royal ship berthing under the shade of willows (Liu Yin Long Zhou), the Tonghui River dividing into the south one and the east one (Bo Fen Su Zhao), plenty of trees standing on the high platform (Gao Tai Cong Shu), a single mountain erecting on the plain (Ping Ye Gu Feng), the Bai River and the Wenyu River converging into the North Canal (Er Shui Hui Liu), and numerous ships sailing on the Grand Canal (Wan Zhou Pian Ji).

Wandering around the Dipamkar Pagoda reminds me of a poem: “when the rain stops, the cattail-made sail is set up, the Dipamkar Pagoda in distance tells that here is Tongzhou”. The Dipamkar Pagoda is the symbol of Tongzhou, also the northernmost end of the three-thousand-kilometer Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal developed in the Ming Dynasty. Roaming on the west bank of the north end of the Grand Canal, I stood right in front of the Pagoda before I know. Due to COVID-19, I was not allowed to visit but appreciate in distance. According to research, the Dipamkar Pagoda, also the Burning Light Stupa, was built in the Northern Zhou Dynasty, rebuilt in 627 in the seventh year of Emperor Taizong of Tang Dynasty, and reconstructed in Liao Dynasty. It was repaired several times during Emperor Chengzongs reign of Yuan Dynasty and Emperor Xianzongs reign of Ming Dynasty; thus, it is also called an “ancient pagoda”.

There are hundreds of millet-sized sariras in light yellow and red enshrined in the pagoda, like jewels, they were picked up and kept in Youshengjiao Temple. The pagoda survived two earthquakes and multiple vandalism, so it had to be reconstructed based on its remaining vajrasana. The octagonal multi-eave pagoda in with thirteen storeies consists of the vajrasana, the body and the top. It is 56 meters tall, the tallest pagoda in Beijing. Those exquisite bricks, arches, statues, decorations are extremely splendid, and all the bricks are painted white, no wonder a poem says that it is “like an ice dragon rocketing to the cloud”. All rafters and eave tips are hanging bells, with 2248 in total. Thus, the pagoda has the largest amount of hanging bells in the world.

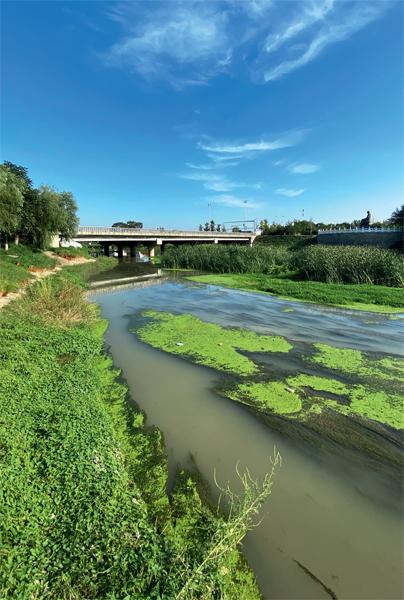

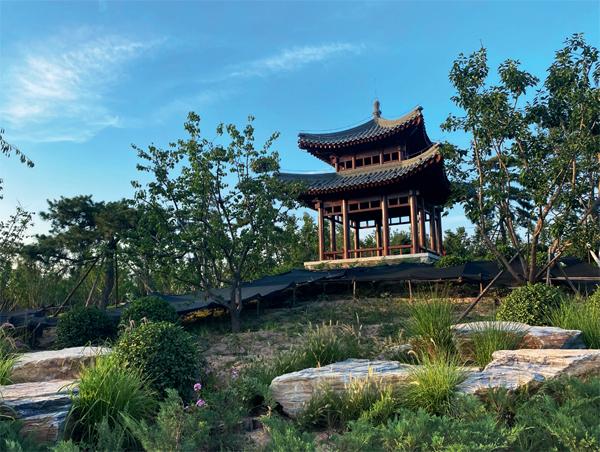

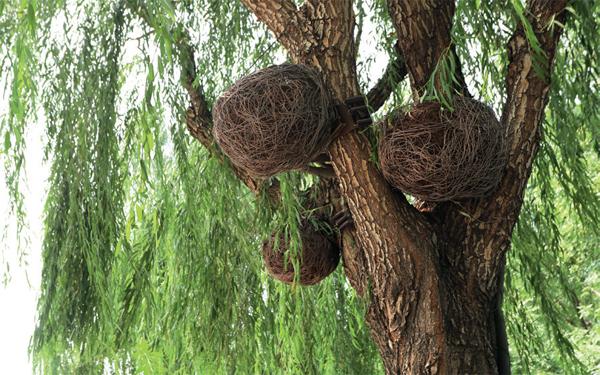

Walking southward along the Grand Canal to its south bank, here is the “Green Heart of the City”, which 2.8 times larger than the Summer Palace, adjacent to the East Sixth Ring Road in the west and the Jingtang Highway in the south. According to the elements of the canal culture belt in the Map of Supervision for the Transportation on the Lu River developed in the Qing Dynasty, there is one road, two willow dikes, three scenic spots and eight key areas for reproducing the canal culture, making the experience of walking in the “green heart” of the city like traveling in a picture.

Entering the Green Heart of the City through the south gate, it is east to find the star-shaped road, planted with beautiful flowers, such as daisies, roses and irises on both sides. On the north side of the main road, there is an ancient style corridor. After searching for much information, I knew that it is actually a single-eave overhanging gable roof structure, built in a traditional way with four beams and eight columns, mixing the style of corridor, hall, pavilion, and pagoda. It is built with red pillars and grey roof, integrating elements of classical Chinese courtyards such as Wan Zi Fu (tens of thousands of well-beings) and Flower Walls. Here is the best place to enjoy the magnificent scenes of the Green Heart of the City. Looking to the east, a square decorated with stones is surrounded by lush trees. The pine creates a paint, the stone brings a view, which is poetic and picturesque. Back to the main road and walking about 500 meters, there is a short wood-structured corridor, built by blue bricks and gray tiles. From the grand wooden structures to the Jiangsu and Zhejiang styled painting, all show the local scenic spots, historical sites and local customs of Tongzhou.

Lets go and take a look at the Green Heart Park of the city. Here is its characteristics: enjoying the cherry blossom in the north and the lake in the south. That is to say, the north side, according to the plan, is the mountainous area with numerous cherry trees. When the spring comes, there will be one more good spot to enjoy the cherry blossom in Beijing, with no need to spend time and money booking tickets to Japan. Standing in the corridor of the cherry blossom hill on the north side, one can also enjoy the lake view on the south side, overlook the clear lake, and visit the side of the lake, plank roads, waterfronts, and wetlands. Walking on the hexagonal road around the park, there are 8-meter wide riding path and 3-meter wide walking path, which are 5.5 kilometers long in total with rest areas along the path and ginkgo trees on both sides. You can walk or sit and enjoy the beautiful scenery. Moving forward to the observation tower at the center of the park which is 20-meter tall will give you a panoramic view of Beijings sub-central administrative district and the Grand Canal.

The Green Heart of the City allows travellers to “enjoy the peach trees and the plum trees in spring, the plane trees in summer, the ginkgo trees in fall, and the pine trees in winter”. It will come soon at the end of September!

Ending

Every scientific achievement on the Grand Canal was not achieved independently; for every form of heritage can be found elsewhere; each cultural phenomenon is universal along the canal. The 2500-year-old canal is not only a witness of various cultures, but also a living culture itself. The Beijing Section of the Grand Canal, which spans six districts, has witnessed the great changes of the city and left ancient cultural marks in Beijing. Numerous “cultures” and “phenomena” integrate here to form a sense of identity and values. After all, we are all descendants of the Grand Canal!