Bones of Culture

2019-12-30byMiaoQian

by Miao Qian

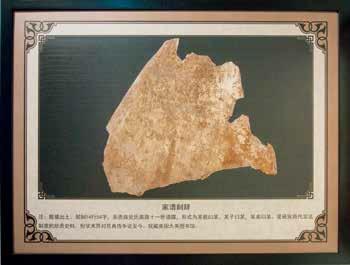

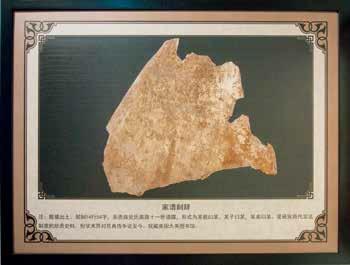

In 2016, the Cambridge University Library in the UK held a large- scale exhibition of ancient scripts to celebrate the 600th anniversary of its establishment. A key part of the exhibits was 17 pieces of Chinese oracle bone inscriptions. Amazingly, the institution allowed visitors not only to see one of the oracle bones up close, but to pick it up and touch it, which became an unprecedented draw.

Truth be told, the touchable oracle bone was the worlds first 3D printed replica made by British archaeologist Dominic Powlesland with a device at the School of Clinical Medicine of the University of Cambridge.

In recent years, Cambridge has made a great achievement in digitalizing more than 600 pieces of oracle bone inscriptions. Now, in the universitys digital library, web users around the world can examine the collections in perfect detail.

According to the statistics collected by Song Zhenhao and Sun Yabing from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), at present, a total of more than 21,000 oracle bones excavated from the Yin Ruins in Chinas Henan Province are collected in 14 foreign countries, including 7,999 in Japan, 7,407 in Canada, 3,141 in Britain, and 1,860 in the United States.

Due to cultural and technical factors, some museums, libraries and institutions collecting oracle bone inscriptions in foreign countries maintain advantages in display methods and technologies, whereas institutions in China hold advantages in analyzing oracle bone inscriptions.

Since 2015, Columbia University Libraries (CUL) in the United States has cooperated with the library of Zhejiang University in China to digitalize the 126 oracle bone pieces in its collection and display the detailed textures of these oracle bones in two-dimensional pictures by using reflective transformation imaging technology.

People can download 3D images of oracle bone inscriptions at the CUL online library and edit the digital images to highlight details from different angles.

In addition to 2D high-definition pictures, the Cambridge University online library also offers a 3D image of an oracle bone. Scientists seamlessly combined images from 1.3 million angles to create a 3D model. Web users can clearly see the characters on the front of the oracle bone, but also its burning and cracking marks.

Such images also offer a much closer look than seeing the real thing while avoiding risk of any damage to the original. Charles Aylmer, head of the Chinese Department at the Cambridge University Library, expressed hope that artificial intelligence technology will one day be able to help combine and restore oracle bone fragments.

It has been a long and complex process for oracle bone inscriptions from China to spread abroad.

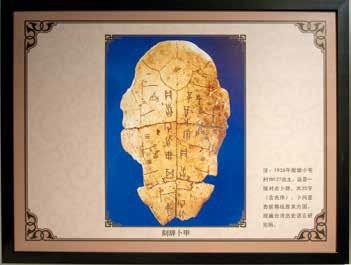

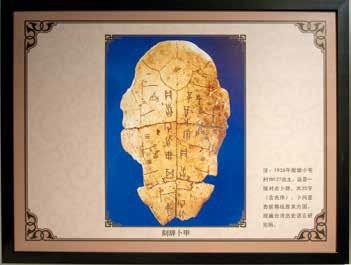

About 120 years ago, after oracle bone inscriptions were first discovered by Chinese people, many foreigners living in China at that time with a keen sense of Chinese culture realized the significance of the fragments. They collected many of them through various channels, many of which ended up in foreign museums.

Most of the foreigners who collected oracle bone inscriptions just after the discovery were educated missionaries, followed by a few diplomats.

The most famous missionaries to actively collect oracle bone inscriptions in China include Briton Samuel Couling and American Frank Chalfant. They began to collect oracle bone inscriptions in China in 1903 and most of their findings entered the British Library collection, which was part of the British Museum in 1911. These became known as the“Couling-Chalfant collection.” Other oracle bones from the CoulingChalfant collection can be also found in the National Museum of Scotland, the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh and the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.

Lionel Charles Hopkins, a British sinologist and diplomat who worked in Tianjin as Chief Ambassador at that time, also had great interest in oracle bones. He purchased more than 900 pieces from Chalfant and shipped them back to Britain for research. After Hopkins died in 1952, his collection was donated by his family to the Cambridge University Library, where it became known as the Hopkins collection.

Another notable collector of oracle bones was James Mellon Menzies, a Canadian missionary who received a bachelors degree in civil engineering from the University of Toronto. He arrived in Anyang, Henan Province in 1910 and lived there for nearly 20 years, during which time he collected tens of thousands of pieces of oracle bones. When war approached, some of his precious collections were left in China and some transported to Canada. In 1960, the Menzies family donated those oracle bones in Canada to the Royal Ontario Museum of Canada, which became the most important Chinese pieces in its collections. That group is now known as the Menzies collection.

To some extent, Western missionaries who ventured to China played an important role in promoting exchange of Eastern and Western cultures.

Over a century since the discovery of oracle bone inscriptions, these relics displayed at different institutions around the world have helped promote Sinology research in Western countries and attract researchers from different cultural backgrounds to study oracle bone inscriptions from contrasting perspectives.