Role of liver biopsy in hepatocellular carcinoma

2019-11-19LucaDiTommasoMarcoSpadacciniMatteoDonadonNicolaPersoneniAbubakerElaminAlessioAghemoAnaLleo

Luca Di Tommaso, Marco Spadaccini, Matteo Donadon, Nicola Personeni, Abubaker Elamin, Alessio Aghemo,Ana Lleo

Abstract The role of liver biopsy in the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has been challenged over time by the ability of imaging techniques to characterize liver lesions in patients with known cirrhosis. In fact, in the diagnostic algorithm for this tumor, histology is currently relegated to controversial cases.Furthermore, the risk of complications, such as tumor seeding and bleeding, as well as inadequate sampling have further limited the use of liver biopsy for HCC management. However, there is growing evidence of prognostic and therapeutic information available from microscopic and molecular analysis of HCC and, as the information content of the tissue sample increases, the advantages of liver biopsy might modify the current risk/benefit ratio. We herein review the role and potentiality of liver biopsy in the diagnosis and management of HCC. As the potentiality of precision medicine comes to the management of HCC, it will be crucial to have rapid pathways to define prognosis, and even treatment, by identifying the patients who could most benefit from target-driven therapies. All of the above reasons suggest that the current role of liver biopsy in the management of HCC needs substantial reconsideration.

Key words: Hepatocellular carcinoma; Liver biopsy; Prognostic factors; Liver cancer;Recurrence; Liquid biopsy

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts for approximately 90% of primary liver cancers and, with a rapidly increasing incidence in the last two decades[1], constitutes a major global health problem[2]. Importantly, HCC mainly develops in the settings of chronic liver injury or cirrhosis[3,4]. Indeed, the high rate of HCC in certain risk groups makes surveillance a cost-effective route to reducing mortality[5]and international societies, including the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), recommend sixmonth interval ultrasounds (US), with or without alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels for cirrhotic patients[6,7].

However, a confident diagnosis of HCC of a liver nodule detected by ultrasonography, in the screening setting, represents a major clinical challenge, and,according to the diagnostic algorithm purposed by Forneret al[8], it is almost impossible with current techniques for nodules with a diameter of less than 1 cm[9].On the other hand, the diagnosis of HCC can be confidently established using imaging techniques if a nodule larger than 1 cm displays a specific imaging pattern[7,10]. The hallmark features of HCC on dynamic computed tomography (CT)scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are an early wash-in combined with late wash-out of contrast agents[10], that, nonetheless, only occur in a minority of patients with small tumors[11]. Moreover, the high specificity and positive predictive value of this pattern in larger lesions have been prospectively validated for the diagnosis of HCC only in cirrhotic livers[10,12-14].

Innovations in cross-sectional imaging, aside from the trend towards a less invasive medical practice, would result in a larger subgroup of patients who can avoid undergoing a liver biopsy for the diagnosis of HCC. On the other hand, the avoidance of biopsies might hamper both the understanding of biological features and the development of targeted therapies for HCC, and the risk of misdiagnosis must always be taken into account. The role of liver biopsy for hepatic nodules thus remains a challenging issue even in the contemporary era. In the present review, we aim to summarize the current clinical guidelines as well as the pros and cons of using liver biopsies in the clinical management of HCC.

DIAGNOSIS OF HCC

Non-invasive diagnosis of HCC, in the setting of liver cirrhosis, is based on a typical imaging diagnostic pattern[4,15]that relies on the peculiar vascular derangement occurring during hepatic carcinogenesis and it is strongly endorsed by EASL, AASLD,and the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver[6,7,16]. All societies concordantly state that the diagnosis of HCC in cirrhotic patients should be based on non-invasive criteria with a strong grade of recommendation and a high level of evidence. Because of their higher sensitivity and ability to analyze the whole liver, CT or MRI should be used first. However, non-invasive criteria can only be applied to cirrhotic patients for liver lesions above 1 cm of diameter, in light of the high pre-test probability, regardless of which imaging modality is utilized and it is not improved by assessing other MRI parameters[17,18]. Iavaroneet aldemonstrated that tumor grade might influence the accuracy of dynamic contrast techniques in the diagnosis of small HCC[19]. Furthermore, non-invasive criteria have not been validated in non - cirrhotic livers.

Of note, HCC in non-cirrhotic patients is likely to be larger at diagnosis[20], since patients are not enrolled in surveillance programs. Yet, the specificity of the imaging diagnostic hallmarks for HCC is lower in the non-cirrhotic liver, as alternative diagnoses are seen more commonly (e.g., hepatocellular adenoma and metastases).Non-invasive diagnostic criteria for HCC have only been validated in patients with cirrhosis who are followed up with, six-month interval, US. Further, only 50% of HCC occurs in cirrhotic patients where HBV infection is endemic[21-23]. Therefore, despite a moderate grade of evidence, EASL strongly recommends that the diagnosis of HCC in non-cirrhotic livers is confirmed using a liver biopsy[6].

Histological diagnosis via liver biopsy may, therefore, be necessary if HCC develops in a non-cirrhotic patient, and if imaging studies are inconclusive for being compatible with HCC. The AASLD does not recommend biopsy for lesions bigger than 1 cm if two different imaging studies yield concordant findings[7]. Liver biopsy is done under CT or US guidance with varying degrees of sensitivity (66%-93% based on tumor size, operator experience, and needle size) and 100% specificity and positive predictive value[24]. Furthermore, a liver biopsy may be needed in patients who are not candidates for curative resection, to establish a diagnosis for the purpose of systemic therapy or transplantation.

PATHOLOGICAL DIAGNOSIS OF HCC AND PROGNOSTIC MARKERS

Tissue-biopsy warrants a simple key-hole view of the lesion under examination. The pathological data obtained at the morphological, phenotypical and molecular level from these tiny fragments may be incomplete or only partially representative.However, it still represents the best option to get information from the lesion itself.Thus, every single diagnostic, prognostic and predictive information represented in the tissue is searched for and reported in the pathological report, to the point that grossing material is saved for this purpose.

Tissue-biopsy is mainly obtained for diagnostic purposes if a conclusive diagnosis of HCC cannot be rendered on imaging. In this setting the differential diagnosis takes into consideration two lesions staying close along the process of hepatocarcinogenesis such as High-Grade Dysplastic Nodule (HGDN) and early HCC[25]and should always be supported by the results of a panel of markers, namely glypican 3 (GPC3), heat shock protein 70 (HSP70), and glutamine synthetase (GS) used in combination[26,27].Indeed, this panel warrants 100% specificity and 72% of sensitivity, while the use of single markers alone can be misleading. GPC3 immunoreactivity can be observed in a few cirrhotic cells and lesions showing up to 10% of immunoreactive cells can also be HGDN[26]. HSP70 can be observed in apoptotic hepatocytes, isolated periseptal hepatocytes, and stellate cells. GS immunoreactivity merits an even greater attention since it is observed in a number of different lesions including: (1) Normal perivenular and periseptal hepatocytes; (2) Focal Nodular Hyperplasia, with a map-like distribution; (3) Exon 7/8 β-catenin mutated hepatocellular adenoma with a faint/focal, patchy immunoreactivity; (4) Exon 3 β-catenin mutated HA, with a strong/diffuse positivity, and (5) HCC[28]. Other diagnostic markers have been investigated but never endorsed in guidelines[29,30].

A progressively larger use of the tissue-biopsy is observed to enroll HCC patient in clinical trials. Even if this revitalization of HCC biopsy does not reflect a real change of attitude toward it, the current situation could be of help to renovate its role. A large amount of information can be searched for in the neoplastic tissue and surrounding parenchyma, and reported in the histopathological diagnosis. These include HCC histotype and grade, microscopic vascular invasion, morpho-molecular type, and the expression of phenotypic markers of prognostic impact such as CK 19 and VETC. In addition, if non-neoplastic liver tissue is available, the degree of fibrosis should be reported as well.

The following HCC histotypes are listed by the upcoming WHO classification:steatohepatitic, clear cells, macrotrabecolar massive, scirrhous, chromophobe,fibrolamellar, neutrophil-rich and lymphocyte-like[31]. The correct definition of the histotype enriches the pathological report with prognostic and/or predictive information. The recently reported macrotrabecolar massive histotype, which represents 5%-10% of all HCC, has a poorer outcome[32,33]; in contrast, the lymphocyterich HCC, a rare histotype showing better prognosis[31], is sustained by the presence of an active immune infiltrate[34]. It may be argued that several histological features can be represented in a single HCC, especially those of larger size. Available data shows that a median of four architectural patterns/cytological variants might coexist within the same HCC[32]. A tissue-biopsy documents only a part of this heterogeneity and, as mentioned above, this may underestimate tumor biology. Tumor size, and therefore tumor heterogeneity, also affects the reliability of HCC grading in the biopsy. The concordance between grading in pre-operative biopsy and the surgical specimen is good/excellent in HCC below 4 cm[19,35]but low in HCC above 7 cm[36]. It is well known that the worse a grade drives the prognosis[37], and therefore a clinically meaningful pathological report might indicate both the predominant as well as the worst grade (in line with what is done for prostatic biopsy). A recent meta-analysis confirmed that histological grading of HCC has an important prognostic role in both liver resection or transplantation; however, it also showed a large heterogeneity on the microscopic assessment of HCC pathology urging standardization[38].

Microscopic vascular invasion (MVI) is a major prognostic feature of HCC and is associated with advanced tumor stage, distant metastasis and adverse outcome[39-41].MVI occurs at the rates of 25%, 40%, 55% and 63% in HCC smaller 3, 3-5, 5-6.5, and bigger 6.5 cm, respectively[42]. Nonetheless, the detection of MVI in a biopsy is fundamentally a chance opportunity. Accordingly, surrogate markers of MVI are intensively investigated. A study on the combination of PIVKA-II with H4K20me2 showed very high specificity and PPV for prediction of MVI in HCC needle biopsies[43,44]. VETC is a peculiar vascular phenotype, originally described by Fanget al[45]. We recently confirmed its strong impact on the prognosis of resectable HCC[46].Moreover we observed the close correlation of VETC with several ominous prognostic features such as MVI. Of interest Fenget al[47]recently showed that VETC+ HCC are those more suitable to sorafenib, prefiguring VETC as a prognostic and predictive marker.

During the last two decades, an increasing understanding of the most abundant molecular alterations of HCC was developed but never translated into daily practice to improve prognostic assessment or therapeutic decision. A recent study firstly demonstrated a strong relationship between molecular and pathological features in HCC[31]and highlighted the existence of two distinct HCC phenotypes sustained by the mutually exclusive CTNNB1 and TP53 mutations. In the first group, HCC presents as well-differentiated tumors with cholestasis and microtrabecular and pseudoglandular patterns of growth; in the second, HCC is mostly poorly differentiated with frequent vascular invasion. Using the corresponding immunohistochemical markers (p53, β-catenin, and GS) we have recently confirmed the clinical-pathological correlations of these two subclasses in the daily clinical practice[46]; however, none of these categories proved to be of prognostic relevance[31,48].Interestingly, the subgroup of HCC correlated to β-catenin pathway activation was recently associated with an exhausted immune infiltrate[49]. This finding, possibly explaining the resistance to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors, prefigures a morphomolecular classification of HCC as having a predictive role[50,51].

The use of stemness-related biomarkers represents the field where the translation of molecular information on clinical practice is more advanced. Several stemness-related markers have been identified and intensively investigated (CK19, EpCAM, CD133,SALL4, NCAM, OV6, CD90, nestin, CD44) and almost all were associated with a more aggressive clinical behavior. In particular, HCCs with CK19 immunostaining in more than 5% of tumor cells show higher recurrence rates and higher rates of lymph node metastasis[52].

A tissue biopsy can be done to distinguish HCC from other primary and secondary malignancies of the liver. Some of these cases may present as poorly differentiated,solid growing carcinomas, in particular, those lesions that previously underwent different lines of treatment. In these cases, the final diagnosis of HCC can hardly be rendered on morphology alone and should be supported by the evaluation of specific markers indicative of hepatocellular differentiation. Those currently used are HepPar-1, Arginase-1, CD10, pCEA, GPC3 and BSEP. In a recent study, Laganaet al[53]investigated their efficiency and showed that BSEP, CD10, and pCEA showed 100%specificity as compared to 97% of GPC3 and HepPar-1 and 94% of Arginase. BSEP and Arginase showed the highest sensitivity (90%).

USE OF LIVER BIOPSY IN CLINICAL MANAGEMENT OF HCC: PROS AND CONS

The main reason for limiting liver biopsies in HCC is the risk of adverse events,possibly impacting on the diagnostic and/or therapeutic pathway. Liver biopsy tecniques and chracteristics of an optimal liver specimen have been descrived in detail[54,55]. The most common complication of liver biopsy is pain that, including mild discomfort, is reported by up to 84% of patients[56]. Severe complications correlated to liver biopsies, including perforation of gallbladder, bile peritonitis, haemobilia,pneumothorax or hemothorax, are extremely rare[57]. Severe bleeding is usually evident within 2-4 hours and occurs in 1 out of 2500-10000 biopsies; nevertheless, late hemorrhage, most likely due to clot dissolution, cannot be neglected[58]. Less severe bleeding, defined as that sufficient to cause pain or reduced blood pressure or tachycardia, but not requiring transfusion or intervention, occurs in approximately 1 out of 500 biopsies[59-65]. Considering that severe hemorrhages are mostly arteriolar, US guidance is not expected to reduce the risk of bleeding, although it reduces the overall amount of complications[66]. Even if the risk of mortality is very uncommon after percutaneous biopsy (1 on 10000), it is usually related to severe hemorrhage, mostly after biopsy of malignant lesions[21,22,24]. Importantly, patient's perspective should be largely considered and informed consent properly aquired.

Furthermore, inserting a needle into a neoplastic lesion could modify the oncologic prognosis of the patient entailing the release of neoplastic cells along the needle path,even if the responsible mechanisms and the real risk of seeding are unclear[67,68]. The most quoted study about seeding risk is a meta-analysis that showed a rate of 2.7% in 1340 biopsies[69]. Nevertheless, adding three more recent series to this meta-analysis we would obtain much lower rates of seeding, even less than 1%[70-72]. Moreover, in most of the reported cases of seeding, its clinical impact is mitigated by the observation that it was usually treated successfully by resective or ablative treatments and did not cause relevant morbidity or mortality[72,73].

As stated above, advances in imaging tools have led to a decrease in requiring biopsy for liver nodules[74,75]. However, the risk of misdiagnosis remains a discussed issue; although possibly influenced by the limited sensibility of the available imaging at the time, Freemanet al[76]retrospectively showed that 20% of 789 patients who underwent liver transplantation for HCC had benign nodules. Furthermore, noninvasive parameters are highly influenced by lesion size[9,11,13].

Finally, it has been recently reported that intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA)can be misdiagnosed as typical HCC in 4% of cases. iCCA is the second most common primary liver cancer worldwide[77]; given its rising incidence[78,79]and poor prognosis,close attention is needed to differentiate iCCA from HCC. Risk factors for iCCA are known to be similar to those for HCC[80,81]and cirrhosis seems to play a pivotal role.Prevalent imaging features of iCCA is a progressive contrast uptake at CT-scan and MRI[48,82-89]but iCCA have been found to be hypervascular in 4% of cases and the enhancement pattern may be similar to HCC at CT-scan and MRI[89-92]. To explain this unusual pattern of iCCA, Huanget al[93]demonstrated the presence of erythrocytes and microvessels, detected by immune-histochemical staining, in all the iCCA presenting with HCC-like contrast enhancement features.

Although histological characteristics may have possible use in both prognostic stratification and detection of the therapeutic target, currently they have no leading role in treatment decisions[7,10]In particular, having the the histological confirmation of HCC in those patients that are deemed to be resectable is not indicated. In these patient, the final histological diagnosis may be properly done on the surgical specimen. Notably, this especially applies when accurate multidisciplinary case discussion is preoperatively performed.

Further, the first-line systemic treatment for HCC with multikinase inhibitors such as sorafenib, is widely prescribed without liver biopsy. Unfortunatelly, no validated targets are avilabe and liver biopsy remains merely diagnostic with no role in prognostic stratification. Importantly, this practice might have largely limited the identification of therapeutic targets, and eventually has contributed to poor stratification in patients. Nevertheless, molecular markers have been explored in the latest years aiming to identify prognostic markers and to improve patient selection for novel treatments in advanced/unresectable HCC[94-98]. In particular, genome profiling of both neoplastic tissue and surrounding liver tissue has been assessed,demonstrating that both the tumor and the non-tumor expression signature predicted tumor recurrence[95]. On the other hand, whereas biomarker-driven enrichments are pursued in most study protocols testing novel anticancer agents, similar approaches in the HCC field have been implemented only in the frame of few clinical trials. Two of them, namely the METIV-HCC[99]and the JET-HCC[100]trials of tivantinib versus placebo, attempted to demonstrate a survival benefit from an investigational MET inhibitor (tivantinib) in patients with elevated MET expression levels, as determined by immunohistochemical analysis. Disappointingly, due to several reasons previously discussed by Rimassaet al[99], both studies eventually failed their respective primary endpoints. Despite the clear frustration that followed these results, the quest for individualized approaches, that may render a conceptual frame for precision medicine in HCC, is still ongoing.

In contrast to other solid tumors such asBRAF-mutated melanomas or lung cancers harboringALKfusion rearrangements, no driver (or “trunk”) mutation leading to oncogenic addiction in HCC is thus far deemed actionable[101]. Conversely, recent investigations suggest that some genomic alterations could lead to the identification of additional molecular targets[102,103]. In a recent study by Schulzeet al, using whole exome sequencing, genetic alterations potentially targetable by already approved drugs were identified in 28% of HCC[104]. Taking advantage from a next-generation sequencing platform, similar data were reported also by Harding and colleagues[51],who found that 24% of patients in their series had at least one potentially actionable mutation that could be the target for currently available Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs. These data therefore highlight the potential usefulness of HCC genotyping with respect to patient care, despite a relatively lower abundance of targetable alterations, as compared to melanoma or lung cancer[105].Further studies investigated the genome-wide profiling of HCC lesions highlighting new possible target areas of chromatin remodeling[106-108]. Indeed, cancers are more complex than their own genome and a complete molecular assessment should theoretically involve transcriptional profiling and micro-environmental characteristics[109-111].

LIQUID BIOPSY IN HCC

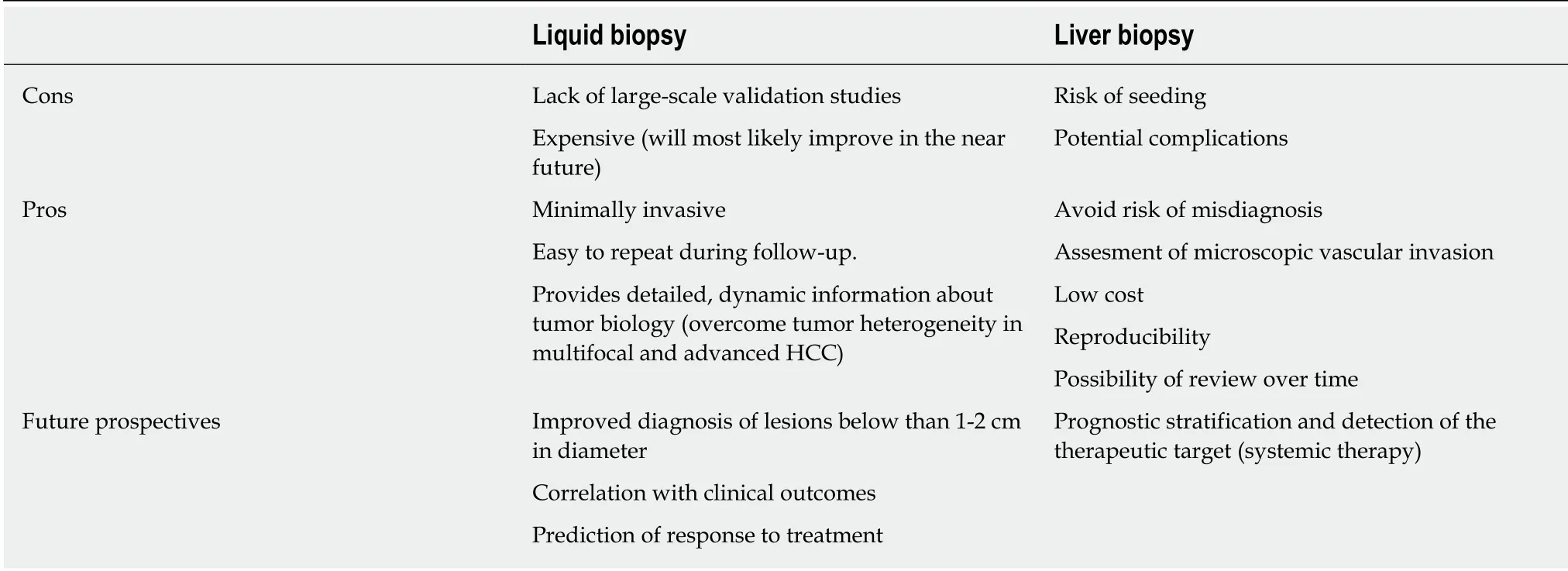

Identifying patients that could benefit from having a liver lesion biopsied, is a challenging effort. At the same time, we aim to obtain critical information in a less invasive way. A liquid biopsy, which entails the analysis of tumor components released into the bloodstream[112], is a minimally invasive procedure and decreases the financial costs and potential complications of tissue biopsies. Liquid biopsies are also easy to repeat during follow-up. Even if an effective liquid biopsy in HCC has not been developed yet, different liquid biopsy markers for HCC early detection and precision medicine have been proposed including circulating tumor cells (CTCs),circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) integrity, somatic mutations, circulating cell-free tumor DNA methylation, and circulating RNA. Most of the studies exploring CTCs in HCC have shown a direct correlation between higher CTC number and poor clinical outcomes[113]. Interestingly, D'Avola and colleagues recently described a method that sequentially combines image flow cytometry and high-density single-cell mRNA sequencing to identify CTCs in HCC patients[114]. Furthermore, a study by von Feldenet alshowed the possible role of circulating DNA methylation markers in the diagnosis, surveillance, and prognosis of HCC[115]. Advances in the field of liquid biopsy hold great promise in improving early detection of HCC, advancing patient prognosis, and ultimately increasing patient survival rates (Table 1). In addition,liquid biopsies could provide a valuable tool to overcome tumor heterogeneity, which is particularly pronounced in multifocal and advanced HCC, both at genomic and transcriptional levels[116].

CONCLUSION

Evaluating the pros and cons of extending or reducing liver nodules biopsy indications, the role of a multidisciplinary case by case evaluation has been highlighted. In our opinion, this approach is going to allow avoiding more biopsies than those which will be added. Thus, coming back to the nowadays, the off-label decision to biopsy a “typical” nodule could only be related to clinical features of higher risk of misdiagnoses such as the increase of atypical markers (i.e., Ca19.9) with normal AFP or the presence of iCCA risk factors (i.e., PSC). Importantly, the decision should be taken after discussion in a multidisciplinary tumor board including radiologists, surgeons, oncologists, pathologists and, hepatologists.

Table 1 Advantages and disadvantages of liquid biopsy

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Ultrasound-based techniques for the diagnosis of liver steatosis

- lnsulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 1 promotes cell proliferation via activation of AKT and is directly targeted by microRNA-494 in pancreatic cancer

- Nucleus tractus solitarius mediates hyperalgesia induced by chronic pancreatitis in rats

- Sustained virologic response to direct-acting antiviral agents predicts better outcomes in hepatitis C virus-infected patients: A retrospective study

- Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in children with symptomatic pancreaticobiliary maljunction: A retrospective multicenter study

- Apparent diffusion coefficient-based histogram analysis differentiates histological subtypes of periampullary adenocarcinoma