沟蚀发生的地貌临界理论计算中数据获取方法及应用

2019-11-08刘晓冰王玉玺张兴义

李 浩,杨 薇,刘晓冰,王玉玺,张兴义

沟蚀发生的地貌临界理论计算中数据获取方法及应用

李 浩1,杨 薇2,刘晓冰1,王玉玺2,张兴义1※

(1. 中国科学院东北地理与农业生态研究所,哈尔滨 150081; 2. 黑龙江省水利科学研究院,哈尔滨 150080)

沟蚀发生是一种地貌临界现象,与沟头处局地坡度及上方汇水面积有关,而沟蚀发生地貌临界理论能够预测沟头可能发生的位置。该文从沟蚀发生地貌临界理论起源、数据获取方式、参数计算方法、影响因素及应用等方面综合评述了该理论的发展及近年来国内外的有关研究。数据获取方式主要包括野外实测、高清遥感影像及地形图测量。参数计算方法包括目视(下限值)法、正交回归(95%置信区间下限)、正交回归(下限值)及分位数回归等。相对剪切力指数值反映区域主要的沟蚀发生机制,临界常数值反映当前特定外界环境下的沟蚀发生临界条件。将相对剪切力指数固定后,临界常数的时间序列变化能够表征外界环境改变对沟蚀发生的影响。人类活动改变了沟头上方汇流环境,进而影响临界条件。沟蚀发生地貌临界理论可获取沟道侵蚀风险较大的区域,为沟道侵蚀防治措施布设提供参考。结合高分辨率地形图,增加表征人类活动影响汇流过程的参数能够丰富沟蚀发生地貌临界理论。该理论与已有沟道侵蚀发展模型结合,可将沟头发生位置和沟道发展过程统一,促进沟道侵蚀全过程的模拟。

地貌;侵蚀;沟;发生;坡度;汇水面积;临界条件

0 引 言

侵蚀沟的动态发展是土壤退化的重要表征。中国将沟蚀分为浅沟侵蚀、切沟侵蚀、冲沟侵蚀和干沟侵蚀等[1],而国外将其分为临时性切沟侵蚀和切沟侵蚀[2]。朱显谟在1956年将现代沟蚀分为浅沟侵蚀和切沟侵蚀,认为浅沟由主细沟演变而来,并能发展为切沟[1]。早期国内学者对浅沟形态的划分有所不同,但均认为能否阻碍横向耕作是浅沟与切沟的本质区别[3-5],与美国的临时切沟侵蚀概念一致。为此,Zhang等[6]在撰写《Encyclopedia of Soil Science》沟蚀(gully)条目时,将中国定义的浅沟侵蚀与美国定义的浅沟侵蚀归为同一类沟蚀类型(ephemeral gully)。坡耕地中沟蚀吞蚀耕地,降低农机具耕作效率,是坡耕地土壤侵蚀的主要方式之一[7]。侵蚀沟道是径流泥沙输送与污染物运移的重要通道,流域侵蚀产沙的重要来源,其发生发展影响现代地貌发育及演化过程[8]。

沟头是沟道侵蚀中发展最剧烈的区域,沟头溯源侵蚀是侵蚀沟发育的主要过程。已有研究表明,侵蚀沟头的生成存在临界条件,即当降雨径流侵蚀力超过土壤阻抗力才能形成,且受土地利用、地表植被、土壤及降雨等因素的综合制约,并发展形成了沟蚀发生地貌临界理论。该理论主要研究沟道生成的区域因素。尽管主细沟是浅沟的初期形态,然而由于主细沟由多条细沟汇集而成,且细沟的空间分布随机性较强[9],因此相对于细沟,该理论更适宜于研究浅沟和切沟的生成临界条件。

侵蚀沟形成的主要原因是径流的增大,而径流的增大多缘于气候或土地利用方式的改变。气候变化导致降雨量增加,径流增大;或者降雨量减少降低植被覆盖度,而后在降雨量短期增加时,径流增大。在土地利用方式方面,毁林开荒或过度放牧均可增大径流。上述过程均受外部环境作用而与沟道自身无关,这难以解释同一区域内沟蚀过程对外部因素响应的不一致性,比如,1条侵蚀沟趋向发育,而临近的侵蚀沟保持稳定。为了解释沟蚀过程对外部因素响应的不一致性,需要增加表征沟道自身因素的内部因素[10],即地貌临界条件。近年来,该理论在数据获取方式、参数分析方法、影响因素及应用领域等方面取得一些进展。本文基于前人的研究,介绍了沟蚀发生地貌临界理论的发展过程及国内外最新研究成果,以期有助于该临界模型的应用推广。

1 沟蚀发生地貌临界理论来源

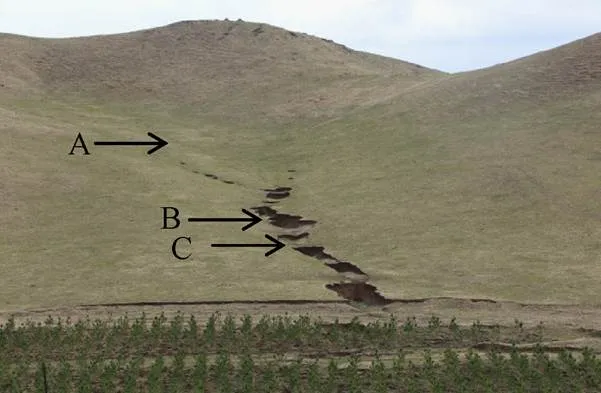

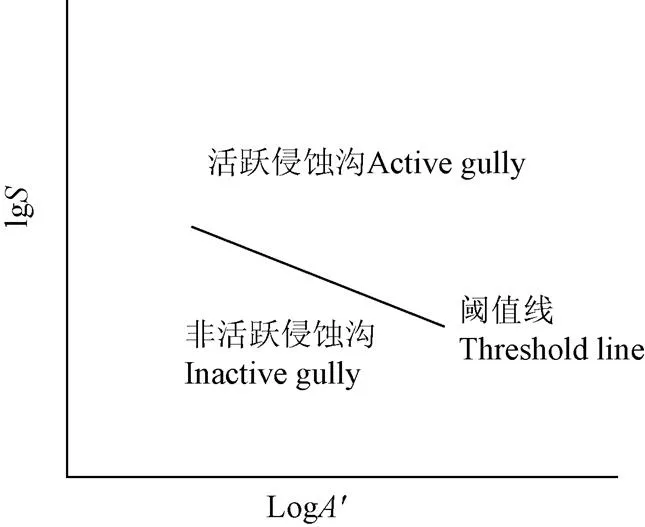

由于采用的基础数据是侵蚀沟头的上方汇水面积(简称)和局地坡度(简称),且结论多为在同一区域下,愈大的上方汇水面积,沟头生成所需要的坡度愈小,因此,被称为沟蚀发生地貌临界理论(图1)。

Horton[11]较早提出沟头生成临界坡长概念,认为当汇流长度超过临界坡长时,侵蚀沟头才能形成。Schumm等[12]发现切沟沟头多形成于局部坡度较大位置。Brice[13]将沟头处及点绘于双对数坐标系内以研究二者的关系。Patton等[14]搜集了美国怀俄明、卡罗拉多等多个州的数十条侵蚀沟及未侵蚀沟谷的地形特征,点绘了坡度最大处的及,并在侵蚀沟点群底部目视绘制直线,作为区分侵蚀沟与未侵蚀沟谷的临界线。该临界线显示侵蚀沟沟头处的与存在反向趋势(inverse relationship),即沟头局部坡度越大,沟头生成所需要的上方汇水面积越小。

注:A,汇流面积较小,未形成沟头;B,汇流面积增大,同时坡度超过阈值,形成坡度;C,汇流面积继续增大,但坡度小于阈值,未形成沟头。

依照Horton[11]沟头生成临界坡长概念,当上方汇流剪切力≥沟道生成临界值Г时,沟头开始生成。此时上方汇流剪切力为

式中为水密度,kg/m3;为径流水力半径,m;S为径流能坡,m/m。对于薄层水流,和S可由径流深及沟头局地坡度代替。

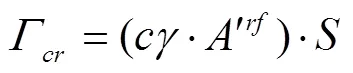

Begin和Schumm[15]根据水力半径()和流量()以及流量()与的经验关系,替代了径流剪切力公式中的,得到沟蚀发生地貌临界条件下Г为

式中Г为临界剪切力,N/m2;为指数;为常数。基于径流剪切力公式,该方程融合了和,建立了沟蚀发生临界剪切力与、关系。

=Г/及=简化[16]为

·=(3)

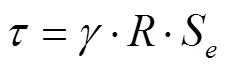

式中为相对剪切力指数,等于双对数坐标系内临界直线斜率的负值,与沟蚀发生机制有关。为临界常数,与当地降雨、植被、土地利用等外界因素有关。活跃与非活跃侵蚀沟位于阈值线的上方和下方(图2)。

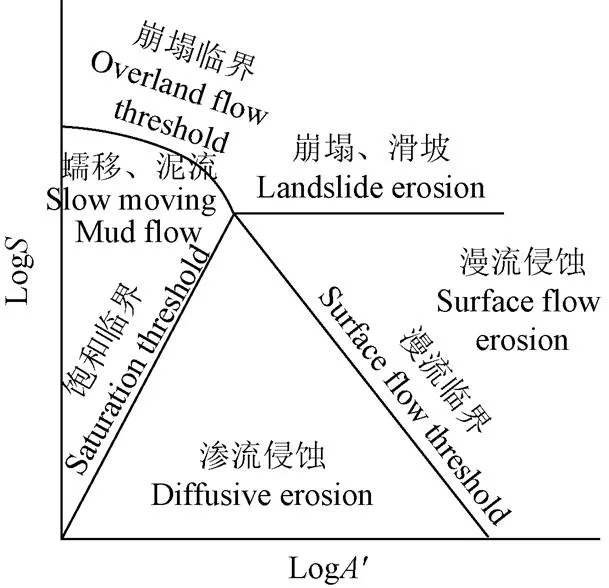

此外,Montgomery等[17-18]从理论上研究了缓坡超渗产流、蓄满产流、渗流及陡坡上薄层崩塌的沟蚀发生临界条件(图3)。这几种沟蚀发生机制作用下形成的侵蚀沟可基本囊括不同坡度、地表覆盖和扰动类型下的人为加速沟道侵蚀类型。

注:A'为上方汇水面积,hm2;S为局地坡度,m·m-1。

图3 不同沟蚀生成条件下的临界条件[17-18]

2 数据采集方法

由于沟蚀发生地貌临界理论研究的是一定区域内沟道发生的-统计规律,需要大量的(数十条或更多)侵蚀沟头上方与样本,因此野外实测、大比例尺地图和遥感影像提取是获取数据的主要方法。值是影响沟蚀发生临界条件分析准确度的主要因素,而野外实测能够准确判断沟头位置,可信度较高。因此,在侵蚀性降雨后对新生成沟头局地坡度及汇水面积开展测量是较为准确的[19]。然而,实测方法费时费力,导致基于该方法开展沟蚀发生临界条件的研究相对较少。大比例尺地形图与遥感影像结合的方法能够快速获取与的现势及历史情况,有助于研究特定区域沟蚀发生临界条件随降雨、土地利用及植被覆盖等侵蚀环境的变化[20-22]。但地形图获取的值可能较实测值偏低(表1)。此外,Vandaele等[19]与Poesen等[23]分别通过实地测量与地形图2种方法,获取了同一区域浅沟生成临界关系方程,发现2种方法获取的值相似,均为0.40左右,而值分别为0.08与0.025,差异较大。

已有大部分研究都是在沟头处测量局地坡度,进而获取上方汇水面积。对不连续、有多个侵蚀沟槽间断出现的情形,与的测量位置应为距离分水岭最近的沟头。也有研究认为,沟头处的与值与侵蚀沟头最初形成的与值有一定的偏差[19]。这是因为在溯源侵蚀沟头的作用下,最初形成的侵蚀沟头向上方移动,离开了原始位置。因此,应当在沟头最初形成的位置测量与值,而该位置很有可能为沟底最大坡度处。由此,预测沟头位置是沟道体系演化理论的关键[24],而且已有沟道侵蚀模型多需要人为指定沟头生成位置,进行沟长沟深演化过程的模拟[25-26]。

近年来,小型无人机应用快速发展,其结合动态测量数据后处理或实时差分动态定位技术,能够准确获取沟道及汇水区的数字地面模型,便于内业解译小型切沟及浅沟与值等信息。由于该技术具有成本低、快速、精度高的优势,目前已应用于沟蚀发生临界地貌条件的相关研究[27]。在三维激光扫描方面,由于该方法主要用于获取单条沟道/沟头的精确侵蚀形态及演化[28],因此其在沟蚀发生临界地貌条件方面的研究相对较少。

表1 已有文献中沟蚀发生地貌临界模型方法及具体参数

3 参数计算方法

目前已发展了多种计算与值的方法,可分为目视+下限值法、正交回归+95%置信区间下限法、正交回归+下限值法和分位数回归法。基本过程均为:1)将沟头局地坡度和上方汇水面积点绘于双对数坐标系中;2)根据一定的原则绘制临界线,该临界线的斜率负值即为相对剪切力指数值;3)根据一定的原则,由式(3)计算临界常数值。因此,不同方法之间的区别为和的计算方式不同。

3.1 目视+下限值法

Begin和Schumm[15]使用侵蚀沟点群底部的两点或多点目视绘制直线,得到值;将点群最低点(lower-most points)的和及值代入到式(3)的左侧,得到值。已有研究[19,35-37]较为完整得描述了该方法。然而,该方法依赖点群底部2个点作出临界线,人为主观性较强,很有可能作出多条临界线,且受极端点的影响较大。因此,实际应用中通常需要剔除异常极值点,以保证临界条件的合理性[32]。

3.2 正交回归+95%置信区间下限法

Gómez 等[20,31]采用正交回归分析获得点群的回归线,以表征侵蚀沟点群的平均地貌临界条件,然后将其95%置信区间的下限作为沟道生成临界线。尽管该方法考虑了侵蚀沟点群-的统计关系,但并不完全符合沟蚀发生的临界条件概念,因为临界线下方仍有部分侵蚀沟点,因此获取的值可能大于实际的沟蚀发生临界值,即可能偏高。

3.3 正交回归+下限值法

Vandekerckhove等[33]改进了3.2中的方法,首先应用正交最小二乘法获得平均地貌临界条件,将临界线平行向下移动到侵蚀点群的底部,从而计算临界常数。该方法既具有大量侵蚀沟道的统计学意义,又兼顾沟道生成的临界条件,考虑了所有沟道侵蚀发生情况下的-统计关系,应用较广[38]。

3.4 分位数回归法

Maugnard等[22]采用分位数回归分析的方法,研究了德国瓦隆尼西亚地区2006年之前、2006年及2009年3个时间段内农用地沟蚀发生的地貌临界条件。他们将分位数设置为0来获取临界线,即认为-点位于该临界线下方的统计学概率为0,并获取相应与值。该方法能有效反映临界区域附近点群的平均权重,优于全体点群统计量,且考虑了离群点信息。同时侵蚀沟样本数应达到50个,以弱化样本数目对临界线回归效果的影响。

4 临界模型因子值及影响因素

4.1 相对剪切力指数b

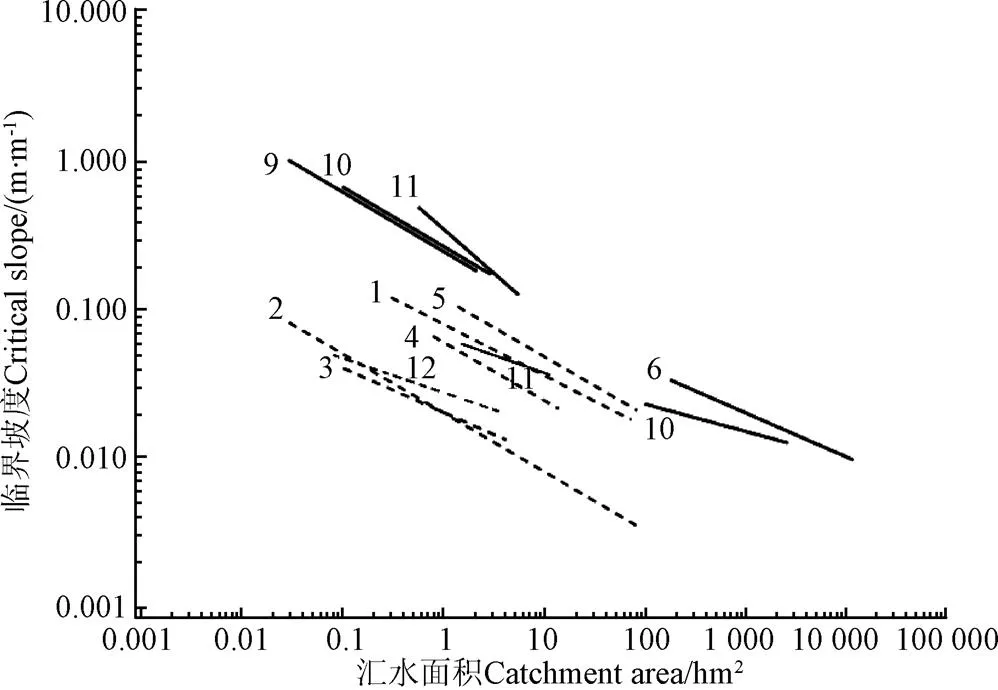

相对剪切力指数值代表研究区域的沟蚀发生机制,因此不同研究区域的值可能取值不同(表1)。Begin等[15]根据水力半径()和流量()以及流量()与流域面积的经验关系和径流剪切力公式,给出理论上取值范围为0.2~0.4。Montgomery等[17]推导了多种沟道侵蚀机制下(缓坡超渗产流、蓄满产流、渗流及陡坡薄层崩塌)临界关系方程形式,给出理论上取值范围为−0.857~0.5。Vandekerckhove等[33]认为当值大于0.2时,主要侵蚀过程为地表径流侵蚀,而值小于0.2时,主要侵蚀过程为地下径流及沟体崩落。值愈低,愈能反映下渗水流促进潜蚀及沟底下切后的沟头沟壁崩塌。Vandaele等[19]认为值应为0.40左右。Poesen等[7]汇总了诸多侵蚀环境及数据获取方法下的沟道生成临界条件文献,结果表明值范围较广(0.10~0.80)(图4)。

4.2 临界常数k

临界常数代表研究区域的外部侵蚀环境,与地质、土壤、气候和植被等因素相关。当研究区域人为活动影响外部侵蚀环境(如土地利用)时,值可能随之发生改变。Torri和Poesen[34]参考已有研究[17,29]将值固定为常数(0.38或0.50),通过值的变化来评估沟头前进与土地利用/植被覆盖度的关系。结果表明,随着植被覆盖度的增加(耕地、草地及林地),沟蚀发生临界常数值也随之增大。同时随着降雨量/降雨强度的降低,沟蚀发生临界常数值随之减小,如半干旱大陆性气候区(如中国黄土高原地区)的值大于温带海洋性气候区(如中欧),而热带气候区的值最低(非洲和巴西等)。Hayas等[39]应用10期遥感影像,研究了1956-2013年降雨、土地利用及植被覆盖对切沟沟头位置及生成临界条件的影响。结果显示,临界常数值受降雨因素影响较大,且日降雨量极值与临界条件的相关性最强,而植被覆盖在降雨量较少时对值的作用更为显著。然而由于临界常数值的影响因素较多,因此缺乏将其与单一影响因素进行定量关系的研究。

1.比利时中部 2.比利时中部 3.葡萄牙 4.法国 5.英国南部:实地调查 6.美国卡罗拉多州 7.美国内华达州 8.美国加利福尼亚州 9.美国俄勒冈州 10.澳大利亚 11.中国黑龙江(1) 12.中国黑龙江(2)

1.Central Belgium 2.Central Belgium 3.Portugal 4.France 5.UK (South Downs) 6.USA (Colorado) 7.USA (Sierra Nevada) 8.USA (California) 9.USA (Oregon) 10.Australia (New SouthWales) 11.China (Heilongjiang)(1) 12.China (Heilongjiang)(2)

注:1、5、7~10均为实地调查;11和12均为实地调查的坡度,地形图的面积;其他为地形图。

Note: 1, 5 and 7-10 from field survey; for 11 and 12, slope from field survey and area from topographic map; others from aerial photos and topographic map.

图4 发育中浅沟与切沟的临界坡度与上方汇水面积关系[7,40]

Fig.4 Relationship between critical slope and catchment area for development of gullies[7,40]

4.3 其他影响因素

上方汇水面积的大小影响沟头生成临界条件。Begin等[15]假设的是在形成洪峰流量时,上方汇水区内所有产流都汇集在沟头的理想情景。而该假设只有在沟头汇水面积较小,或降雨历时足够长时才能成立,即沟头处流量才能用上方汇水面积替代。在上方汇水面积较大或降雨历时较短的情形下,汇水区产流并不一定能全部到达侵蚀沟头,即形成洪峰流量时沟头上方汇水区域小于全部汇水区,导致值偏小[32]。Rossi等[41]从理论上推导了局部汇水区产流汇集到沟头对-关系因子值的影响,建议避免将该理论应用于大型侵蚀沟的生成机制研究。

农耕地中的道路降低了降雨入渗速率,增大了集中径流量与速度,改变了流域汇流时间,可能导致侵蚀沟生成所需临界坡度变小,因此-临界关系可用于道路对侵蚀沟生成影响的研究。Katz等[42]提取了美国科罗拉多州林地中道路排水导致的侵蚀沟沟头(简称区域1)的和值,并绘制了临界线。同时获取了在道路排水作用下有集中径流但未形成侵蚀沟(简称区域2),以及林地自然集中径流但未形成侵蚀沟(简称区域3)的点位和值,并点绘在区域1的临界线图中(参考图2)。结果显示,区域1与2的-点分别位于临界线的上方和下方,表明在道路集中径流的作用下,该区域侵蚀沟头的生成存在明确的临界关系。同时区域3的-点分布在临界线的上方与下方,说明该临界线不能明确林地自然径流下是否形成侵蚀沟,即自然径流下与道路集中径流下侵蚀沟生成的地貌临界条件是不同的。

5 沟道生成临界理论在中国的应用

中国学者在调查与研究黄土高原浅沟和切沟的地貌临界条件方面做了不懈的努力,积累了宝贵的数据。罗来兴等[43]将黄河中游黄土丘陵区侵蚀沟划分为浅沟、切沟、冲沟、坳沟及河沟。陈永宗[3]对各种侵蚀沟平均汇水面积与坡度进行了统计,并点绘在半对数和对数图中,发现罗来兴划分的侵蚀沟类型满足了沟谷发育过程的连续性和阶段性要求,可将黄土丘陵区侵蚀沟发展的顺序概化为浅沟→切沟→冲沟→坳沟→河沟。其他有关黄土高原的地貌临界条件研究多集中于浅沟的临界坡度与临界坡长的上下限等的统计分析[5,44-46]。

随着3S技术的发展,近些年来中国学者应用沟蚀发生临界理论开展了定位研究[47]。约70%的研究集中于黄土高原区域,而在东北黑土区[47]、南方红壤区[48]、长江上游紫色丘陵区[49]和内蒙古风沙区[50]也有部分研究。在研究方法上,多使用野外实测或高分辨率遥感影像获取侵蚀沟头位置,进而使用地形图获取侵蚀沟头局地坡度及上方汇水面积。由于1:10 000地形图是目前能够获取到的覆盖面积最广、最为详细的地形图,因此被广泛应用。在阈值线和参数获取方式上,几乎所有研究均使用目视(下限值)法,对不同计算方式可能带来误差的考虑较少。

在具体研究方面,Cheng等[51-52]使用实时差分定位(real-time kinematic,RTK)实测汇水区地形图及沟头处坡度,研究了黄土高原、东北黑土区、内蒙古风沙区等沟蚀发生地貌临界条件。张永光等[40,47,53]等搜集了东北黑土区鹤山农场2个小流域内的浅沟和切沟和数据,通过下限点目视绘制临界线,并对比了二者的-关系式。结果表明,浅沟和切沟的值近似(0.141与0.148),可能是因为研究区沟蚀生成机制是近似的;同时值有一定差异(0.072与0.052),表明浅沟与切沟生成的地貌临界条件是不同的。李斌兵等[54]在黄土高原丘陵区借助RTK实测数据及GIS方法,建立了浅沟侵蚀和切沟侵蚀发生判定式,并提取了浅沟和切沟侵蚀分布区与野外调查结果相当吻合。

此外,已有研究表明,垄作影响东北黑土区坡面汇流侵蚀过程。相对于自然坡面,横坡垄作可能扩大或减少上游汇水面积,而顺坡垄作明显加剧了坡面汇流与侵蚀过程[55],从而影响沟蚀发生临界条件。因此,在东北黑土区应用时,需要在模型中添加考虑垄作的复合地形因子,以达到更好的预测效果。

6 结论与展望

沟蚀发生地貌临界理论将沟头生成视为一种临界现象,适宜浅沟或小型切沟的生成研究。沟头位置是在已有多场降雨作用下形成的,能够代表区域内当前沟蚀发生的平均地貌临界条件。基于时间序列的沟蚀发生地貌临界条件,可用于研究自然或人为因素(降雨、植被类型和土地利用等)对沟头生成过程的影响及变化。

沟蚀发生地貌临界理论有助于沟道侵蚀防治措施的布设。该理论能够给出沟蚀发生的临界条件,进而预测沟头位置的空间分布,即可能发生沟道侵蚀的区域。因此可针对沟道侵蚀风险性大的区域布设沟道防治措施。鉴于已有研究数据处理方式较为一致,可通过对比不同生态类型区内的沟道生成阈值,为沟道侵蚀防治总体规划的区域差异化布设提供参考。

人为扰动是现代沟道形成的主要原因。人类活动如修建梯田和农田道路,及改垄等改变了农田微地貌,影响坡面汇水过程,进而改变沟头上方汇水面积。而高分辨率地形图能够反映农田微地貌的改变。近年来高清遥感影像、基于照片的三维重建及激光雷达技术的发展,促进了高分辨率地形图的获取。因而结合上述新技术获取的高分辨率地形图,应用沟蚀发生地貌临界理论可量化人为活动对沟道形成的影响。

与已有沟道侵蚀发展模型结合亦是沟蚀发生地貌临界理论的另一发展方向。目前大部分的沟道侵蚀发展模型(如AnnAGNPS,REGEM)可以模拟沟道发展过程,但多需要人为确定沟头位置,而沟蚀发生地貌理论的主要作用是预测沟头可能发生的位置。因此二者的结合可将沟头发生位置和沟道发展过程整合,促进沟道侵蚀全过程的模拟。

[1] 朱显谟. 黄土区土壤侵蚀的分类[J]. 土壤学报,1956,4(2):99-115.

[2] Foster G. Understanding ephemeral gully erosion[M]// Board on Agriculture, National Research Council. Committee on Conservation Needs and Opportunities, Assessing the National Resources Inventory. Washington D C: National Academy Press, 1986:90-125.

[3] 陈永宗. 黄河中游黄土丘陵区的沟谷类型[J]. 地理科学,1984,4(4):35-41.

Chen Yongzong. The classification of gully in hilly loess region in the middle reaches of the Yellow River [J]. Scientia Geographica Sinica, 1984, 4(4): 35-41. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[4] 黄秉维. 陕甘黄土区域土壤侵蚀的因素和方式[J]. 地理学报,1953,20(2):63-75.

[5] 刘元保,朱显谟,周佩华,等. 黄土高原坡面沟蚀的类型及其发生发展规律[J]. 水土保持研究,1988(1):9-18.

[6] Zhang Fenli, Chihua H. Gully Erosion[M]//Encyclopedia of Soil Science. Boca Raton, USA: CRC Press, 2006.

[7] Poesen J, Nachtergaele J, Verstraeten G, et al. Gully erosion and environmental change: Importance and research needs[J]. Catena, 2003, 50(2): 91-133.

[8] 刘宇. 土壤侵蚀研究中的景观连通度:概念、作用及定量[J]. 地理研究,2016,35(1):195-202.

Liu Yu. Landscape connectivity in soil erosion research: Concepts, implication and quantification[J]. Geographical Research, 2016, 35(1): 195-202. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[9] 和继军,宫辉力,李小娟,等. 细沟形成对坡面产流产沙过程的影响[J]. 水科学进展,2014,25(1):90-97.

He Jijun, Gong Huili, Li Xiaojuan, et al. Effects of rill development on runoff and yielding processes[J]. Advances in Water Science, 2014, 25(1): 90-97. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[10] Schumm S A. Geomorphic thresholds: The concept and its applications[J]. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 1979, 4(4): 485-515.

[11] Horton R E. Erosional development of streams and their drainage basins: Hydrophysical approach to quantitative morphology[J]. Journal of the Japanese Forestry Society, 1945, 56(3): 275-370.

[12] Schumm S A, Hadley R F. Arroyos and the Semiarid Cycle of Erosion[J]. American Journal of Science, 1957, 255(3): 161-74.

[13] Brice J C. Erosion and deposition in the loess-mantled Great Plains, Medicine Creek drainage basin, Nebraska[M]. US: US Government Printing Office, 1966.

[14] Patton P C, Schumm S A. Gully erosion, Northwestern Colorado: A threshold phenomenon [J]. Geology, 1975, 3(2): 88-90.

[15] Begin Z B, Schumm S A. Instability of alluvial valley floors: A method for its assessment[J]. Transactions of the ASAE, 1979, 22(2): 0347-0350.

[16] Leopold L B, Wolman M G, Miller J P. Fluvial processes in geomorphology[J]. Geographical Journal, 1964, 131(1): 454-456.

[17] Montgomery D R, Dietrich W E. A physically based model for the topographic control on shallow landsliding[J]. Water Resources Research, 1994, 30(4): 1153-1171.

[18] Prosser I P, Abernethy B. Predicting the topographic limits to a gully network using a digital terrain model and process thresholds[J]. Water Resources Research, 1996, 32(7): 2289-2298.

[19] Vandaele K, Poesen J, Govers G, et al. Geomorphic threshold conditions for ephemeral gully incision[J]. Geomorphology, 1996, 16(2): 161-173.

[20] Gómez Gutiérrez Á, Schnabel S, Lavado Contador F. Gully erosion, land use and topographical thresholds during the last 60 years in a small rangeland catchment in SW Spain[J]. Land Degradation & Development, 2009, 20(5): 535-550

[21] López A H, Poesen J, Vanwalleghem T. Rainfall and vegetation effects on temporal variation of topographic thresholds for gully initiation in mediterranean cropland and olive groves[J]. Land Degradation & Development, 2017, 28(8): 2540-2552.

[22] Maugnard A, Van Dyck S, Bielders C L. Assessing the regional and temporal variability of the topographic threshold for ephemeral gully initiation using quantile regression in Wallonia (Belgium)[J]. Geomorphology, 2014, 206: 165-177.

[23] Poesen J, Govers G, Boardman J, et al. Gully erosion in the loam belt of Belgium: Typology and control measures[C]// Proceedings of the Soil Erosion on Agricultural Land. Coventry, UK: British Geomorphological Research Group, 1990.

[24] Montgomery D R, Dietrich W E. Where do channels begin? [J]. Nature, 1988, 336(6196): 232-234.

[25] Li H, Cruse R M, Bingner R L, et al. Evaluating ephemeral gully erosion impact onL. yield and economics using AnnAGNPS [J]. Soil & Tillage Research, 2016, 155: 157-165.

[26] Bingner R L, Theurer F D, Yuan Y. AnnAGNPS Technical Processes Documentation (Version 4.0)[M]. US: USDA-ARC National Sedimentation Laboratory & USDA-NRCS National Water and Climate Center, 2007.

[27] Gudino-Elizondo N, Biggs T, Castillo C, et al. Measuring ephemeral gully erosion rates and topographical thresholds in an urban watershed using unmanned aerial systems and structure from motion photogrammetric techniques[J]. Land Degradation & Development, 2018, 29(6): 1896-1905.

[28] Rengers F K, Tucker G E. The evolution of gully headcut morphology: A case study using terrestrial laser scanning and hydrological monitoring [J]. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, 2015, 40(10): 1304-1317.

[29] Knapen A, Poesen J. Soil erosion resistance effects on rill and gully initiation points and dimensions[J]. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, 2010, 35(2): 217-228

[30] 苏子龙,崔明,范昊明. 东北漫岗黑土区防护林带分布对浅沟侵蚀的影响[J]. 水土保持研究,2012,19(3):20-23.

Zhang Zilong, Cui Ming, Fan Haoming.Effect of protective forest belt on ephemeral gully erosion in Northeast China with black soils[J]. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 2012, 19(3): 20-23. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[31] Vandekerckhove L, Poesen J, Wijdenes D O, et al. Topographical thresholds for ephemeral gully initiation in intensively cultivated areas of the Mediterranean[J]. Catena, 1998, 33(3/4): 271-292.

[32] Vanwalleghem T, Poesen J, Nachtergaele J, et al. Characteristics, controlling factors and importance of deep gullies under cropland on loess-derived soils[J]. Geomorphology, 2005, 69(1/2/3/4): 76-91.

[33] Vandekerckhove L, Poesen, J, Oostwoud Wijdenes D, et al. Thresholds for gully initiation and sedimentation in Mediterranean Europe[J]. Earth Surface Processes & Landforms, 2000, 25(11): 1201-1220.

[34] Torri D, Poesen J. A review of topographic threshold conditions for gully head development in different environments[J]. Earth-Science Reviews, 2014, 130: 73-85.

[35] Poesen J W A, Hooke J M. Erosion, flooding and channel management in Mediterranean environments of southern Europe[J]. Progress in Physical Geography, 2016, 21(2): 157-199.

[36] 胡刚,伍永秋.发生沟蚀(切沟)的地貌临界研究综述[J]. 山地学报,2005,23(5):565-570.

Hu Gang, Wu Yongqiu. Progress in the study of geomorphic threshold theory in channel (gully) erosion[J]. Journal of Mountain Science, 2005, 23(5): 565-570. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[37] 刘晓冰,张兴义. 沟道侵蚀的多样性和发生过程及研究展望[J]. 土壤与作物,2018(2):90-102.

Liu Xiaobing, Zhang Xingyi. Gully erosion: diversity, processes and prospects[J]. Soils and Crops, 2018(2): 90-102. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[38] Morgan R P C, Mngomezulu D. Threshold conditions for initiation of valley-side gullies in the Middle Veld of Swaziland[J]. Catena, 2003, 50(2): 401-414.

[39] Hayas A, Vanwalleghem T, Laguna A, et al. Reconstructing long-term gully dynamics in Mediterranean agricultural areas[J]. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 2017, 21(1): 235-249.

[40] 张永光,伍永秋,刘洪鹄,等. 东北漫岗黑土区地形因子对浅沟侵蚀的影响分析[J]. 水土保持学报,2007,21(1): 35-38.

Zhang Yongguang, Wu Yongqiu, Liu Honghu, et al.Effect of topography on ephemeral gully erosion in Northeast China with black soils[J]. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 2007, 21(1): 35-38. (in Chinese with English abstract

[41] Hayas A, Vanwalleghem T, Laguna A, et al. Reconstructing long-term gully dynamics in Mediterranean agricultural areas[J]. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 2017, 21(1): 235-249.

[41] Rossi M, Torri D, Santi E. Bias in topographic thresholds for gully heads[J]. Natural Hazards, 2015, 79(S1): 51-69.

[42] Katz H A, Daniels J M, Ryan S. Slope-area thresholds of road-induced gully erosion and consequent hillslope-channel interactions[J]. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, 2014, 39(3): 285-295.

[43] 罗来兴. 划分晋西、陕北、陇东黄土区域沟间地与沟谷的地貌类型[J]. 地理学报,1956,23(3):201-222.

Luo Laixing. A tentative classification of landforms in the Loess Plateau[J]. Acta Geographica Sinica, 1956, 22(3): 201-222. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[44] 张科利,唐克丽,王斌科. 黄土高原坡面浅沟侵蚀特征值的研究[J]. 水土保持学报,1991,5(2):8-13.

Zhang Keli, Tang Keli, Wang Binke. A study on characteristic value of shallow gully erosion on slope farmland in the Loess Plateau[J]. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 1991, 5(2): 8-13. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[45] 姜永清,王占礼. 瓦背状浅沟分布特征分析[J]. 水土保持研究,1999,6(2):181-184.

Jiang Yongqing, Wang Zhanli, Hu Guangrong, et al. Distribution features of shallow gully[J]. Research of Soil and Water Conservation, 1999, 6(2): 181-184. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[46] 秦伟,朱清科,赵磊磊,等. 基于RS和GIS的黄土丘陵沟壑区浅沟侵蚀地形特征研究[J]. 农业工程学报,2010,26(6):58-64.

Qin Wei, Zhu Qingke, Zhao Leilei, et al. Topographic characteristics of ephemeral gully erosion in loess hilly and gully region based on RS and GIS[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering (Transactions of the CSAE), 2010, 26(6): 58-64. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[47] 胡刚,伍永秋,刘宝元,等. 东北漫川漫岗黑土区浅沟和切沟发生的地貌临界模型探讨[J]. 地理科学,2006,26(4): 449-454.

Hu Gang, Wu Yongqiu, Liu Baoyuan, et al. Geomorphic threshold model for ephemeral gully incision in rolling hills with black soil in Northeast China[J]. Scientia Geographica Sinica, 2006, 26(4): 449-454. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[48] 杨文利,朱平宗,赵建民,等. 南方红壤丘陵区马尾松人工林地浅沟形态特征[J]. 西北农林科技大学学报:自然科学版,2019,47(8):100-108.

Yang Wenli, Zhu Zongping, Zhao Jianmin, et al. Morphological characteristics of ephemeral gullies ofplantations in the Red Soil Hilly Region of southern China[J]. Journal of Northwest A & F University: Natural Science Edition, 2019, 47(8): 100-108. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[49] 何福红. 基于“3S”技术的沟蚀研究方法构建与应用[D].北京:中国农业科学院,2006.

[50] 程宏,王升堂,伍永秋,等. 坑状浅沟侵蚀研究[J]. 水土保持学报,2006,20(2):39-41.

Cheng Hong, Wang Shengtang, Wu Yongqiu, et al. Study on hole-ephemeral gullies erosion [J]. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 2006, 20(2): 39-41, 58. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[51] Cheng H, Wu Y, Zou X, et al. Study of ephemeral gully erosion in a small upland catchment on the Inner-Mongolian Plateau[J]. Soil and Tillage Research, 2006, 90(1/2): 184-193

[52] Cheng H, Zou X, Wu Y, et al. Morphology parameters of ephemeral gully in characteristics hillslopes on the Loess Plateau of China[J]. Soil and Tillage Research, 2007, 94(1): 4-14

[53] Zhang Y, Wu Y, Liu B, et al. Characteristics and factors controlling the development of ephemeral gullies in cultivated catchments of black soil region, Northeast China[J]. Soil and Tillage Research, 2007, 96(1/2): 28-41.

[54] 李斌兵,郑粉莉,张鹏. 黄土高原丘陵沟壑区小流域浅沟和切沟侵蚀区的界定[J]. 水土保持通报,2008,28(5):16-20.

Li Binbing, Zheng Fenli, Zhang Peng. Geomorphic threshold determination for ephemeral gully and gully erosion areas in the loess hilly gully region[J]. Bulletin of Soil and Water Conservation, 2008, 28(5): 16-20. (in Chinese with English abstract)

[55] 宋玥,张忠学. 不同耕作措施对黑土坡耕地土壤侵蚀的影响[J]. 水土保持研究,2011,18(2):14-16.

Song Yue, Zhang Zhongxue. The effect of different tillage measures on soil erosion in slope farmland in black soil region[J]. Research of Soil and Water Conservation, 2011, 18(2): 14-16. (in Chinese with English abstract)

Data obtained method and application for topographic threshold theory calculation of gully initiation

Li Hao1, Yang Wei2, Liu Xiaobing1, Wang Yuxi2, Zhang Xingyi1※

(1.150081,; 2.150080,)

Gully initiation topographic threshold theory describes gully initiation condition, and is represented by the size of catchment that controls discharge, and local slope at the channel head that controls the velocity of runoff. The main cause of gully formation is excessive (sub) surface runoff, a condition that might be brought about by either climate change or alternations in land use. In this study, this theory was reviewed from the following aspects: theory development, data sources, threshold value calculating methods, influencing factors and applications. The gully initiation threshold concept was originally developed to explain the onset of instability in 1 gully while its neighbours remained stable. The relative area (or shear stress) exponent was generally interpreted in relation to the gully erosion process in the catchment. Values higher than 0.2 were associated with erosion by surface runoff and those lower than 0.2 indicated subsurface processes or mass movement. The threshold coefficient reflected the resistance of the site to gully head development, affected by rainfall, land use, etc. The threshold values variation also depended on the methodology, including field reconnaissance survey and high-resolution remote sensing images as well as digital elevation model. The latter were more convenient for data acquisition, although field reconnaissance survey data would be more accurate. With fast development of unmanned aerial vehicles, high spatial resolution orthophotos derived from structure-from-motion photography could be used to identify the location of gully heads and corresponding catchment size and local slope values. In the early research, the topographic threshold straight line was eye-fitted through the “lower-most” points in a log–log scatter plot. The negative slope of that line was equal to relative area exponent value. Then the threshold value could be obtained as the intercept. Since this threshold line was manually drawn, it did not have statistical meaning. This method might also be problematic as multiple thresholds could exist, and the threshold line was very sensitive to extreme values. Based on orthogonal regression, the mean threshold line was fitted through the data-points. Then the minimum threshold line was defined either by the lower limit of the 95% prediction confidence interval around the mean threshold line, or parallel line below the lower limit of the scatter of the data. Quantile regression was recommended because it was statistically-based and robust to outliers. Since the domination mechanisms of gully initiation would not change within decades in a certain region, the relative area exponent could be fixed as a constant value. According to this hypothesis, the threshold coefficient of muti-periods could be used to investigate human effect on gully initiation. In China, about 70% of the research was carried out in the Loess Plateau region. The 1:10 000 topographic map was widely used to obtain local slope and catchment size, since this was the most extensive and detailed topographic map currently available. Most studies extracted the threshold conditions by using the eye-fitted line through the “lower-most” points, and few consideration was carried out for the potential errors between different calculation methods. Road construction altered the surface hydrology, and the road surface condition reduced the critical slope for a given drainage area required for gullying. Agricultural reclamation was the main reason for gully development in the Northeastern China, where ridge tillage was widely applied. Contour ridge changed runoff pathways and rearranged drainage networks, and longitudinal ridge accelerated flow concentration. Consideration of ridge-direction effect was important for gully initiation topographic threshold theory applications in this region. Using high-resolution topographic maps and adding the parameters that characterized the human activities effect on concentrated surface runoff could enrich the gully initiation topographic threshold theory. Current gully erosion model could simulate gully development while gully head needed to be mannually located. Hence gully initiation topographic threshold theory could be promoted by combining with such models, since this theory could predict where gully initiated.

geomorphology; erosion; gully; initiation; slope; catchment area; threshold condition

李 浩,杨 薇,刘晓冰,王玉玺,张兴义. 沟蚀发生的地貌临界理论计算中数据获取方法及应用[J]. 农业工程学报,2019,35(18):127-133.doi:10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2019.18.016 http://www.tcsae.org

Li Hao, Yang Wei, Liu Xiaobing, Wang Yuxi, Zhang Xingyi. Data obtained method and application for topographic threshold theory calculation of gully initiation[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering (Transactions of the CSAE), 2019, 35(18): 127-133. (in Chinese with English abstract) doi:10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2019.18.016 http://www.tcsae.org

2019-04-06

2019-08-10

国家重点研发项目(2017YFC0504200);国家自然科学青年基金(41601289)联合资助

李 浩,助理研究员,博士,主要从事地理信息系统与沟道侵蚀研究。Email:lihao@iga.ac.cn.

张兴义,研究员,博士,博士生导师,主要从事黑土生态研究。Email:zhangxy@iga.ac.cn

10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2019.18.016

S157.1

A

1002-6819(2019)-18-0127-07