Autoimmune hepatitis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: A case series and review of the literature

2019-10-11RoongruedeeChaiteerakijAnapatSanpawatAnchaleeAvihingsanonSombatTreeprasertsuk

Roongruedee Chaiteerakij, Anapat Sanpawat, Anchalee Avihingsanon, Sombat Treeprasertsuk

Abstract

Key words: Autoimmune hepatitis; Human immunodeficiency virus; Liver biopsy;Immunosuppression; Autoimmunity; Antiretroviral therapy; Case report

INTRODUCTION

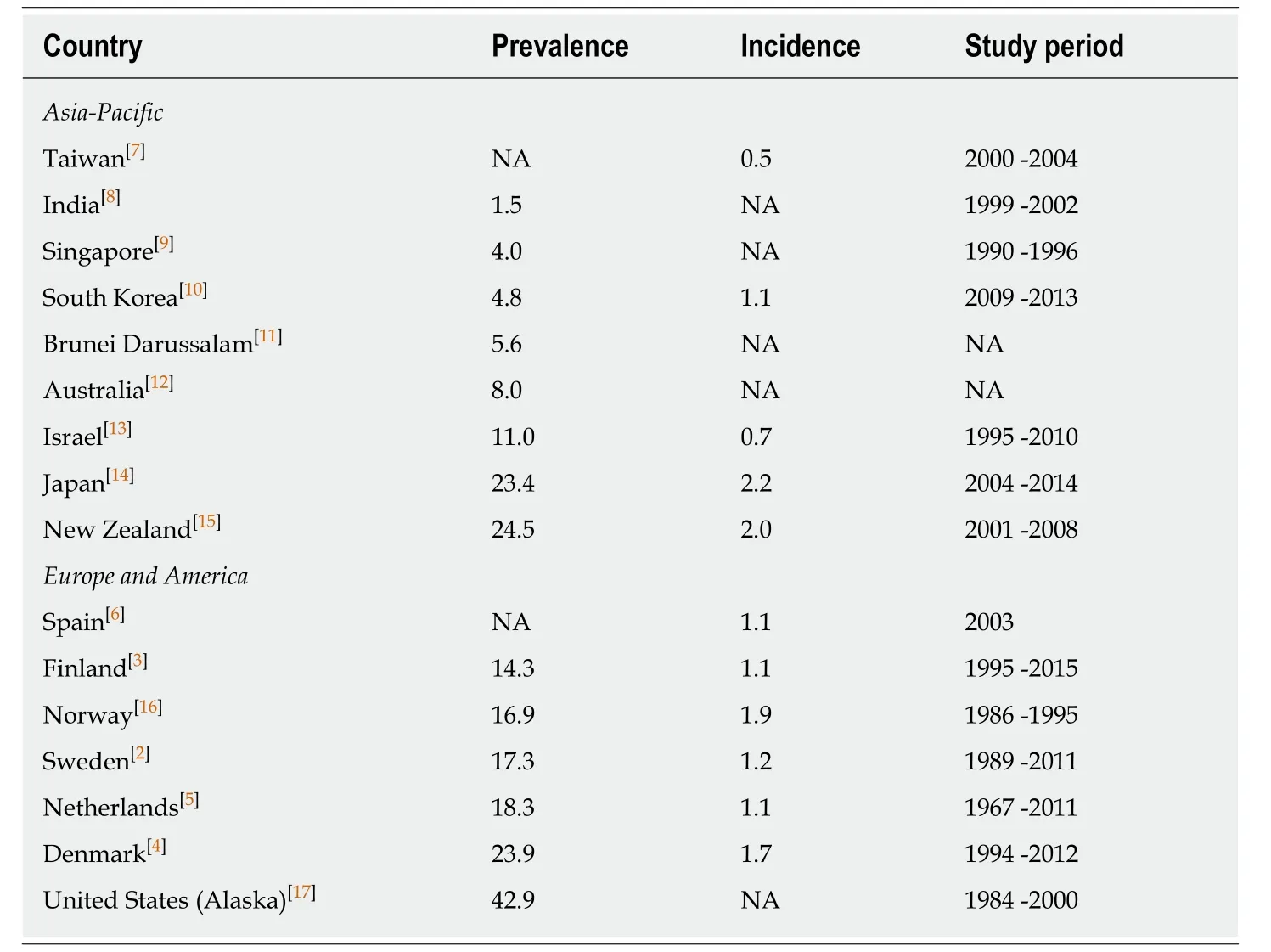

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is considered to be a relatively rare chronic liver disease.Its incidence, prevalence and clinical phenotype vary considerably by geographical area. The annual incidence of AIH ranges from 0.5-2.2 per 100000 individuals[1].During the past 2 decades, the incidence of AIH has remained stable in Sweden and Finland[2,3]but has increased in certain countries, such as Denmark, Netherlands and Spain[4-6]. The prevalence of AIH in the Asia-Pacific region is lower than that reported in Europe and America (Table 1)[2-17]. Within the Asia-Pacific region, India has the lowest prevalence per 100,000 individuals of 1.5, while Japan and New Zealand have the highest prevalence of 23.4 and 24.5, respectively[8,14,15]. Among Western countries,Finland has the lowest prevalence per 100000 individuals of 14.3, while Alaska has the highest prevalence of 42.9[3,17]. Variations in disease occurrence across different countries suggest that some environmental factors may play a role in AIH development.

AIH is a chronic liver disease with progressive liver parenchymal inflammation and damage caused by regulatory T-cell dysfunction-induced hyperreactive responses. The disease is characterized by hypergammaglobulinemia, the presence of circulating autoantibodies, and typical histologic features including interface hepatitis, lymphoplasmacytic cell infiltration, liver cell rosette formation,emperipolesis and response to immunosuppressive therapy[18]. It has been suggested that a genetic predisposition, molecular mimicry and environmental factors are associated with the development of AIH[19].

The diagnosis of AIH relies on criteria comprising clinical, serological, and histological features. Clinical presentation is heterogeneous, ranging from no symptoms to acute or chronic hepatitis to acute liver failure or cirrhosis. Initial laboratory tests show elevation of aminotransaminase enzymes. Although abnormal liver chemistry commonly occurs in HIV-affected individuals (approximately 27%),AIH is rarely suspected at presentation. The most common cause of liver enzyme elevation in patients with HIV infection is nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, followed by alcohol intake, and viral hepatitis B and C infection[20]. Despite the rarity of this disease, the number of reports of AIH in HIV-infected individuals has increased in recent years[21-39]. Here, we present 13 HIV-infected patients who developed AIH aftertreatment with antiretroviral therapy. The characteristics of previously reported HIVinfected patients with AIH are also summarized.

Table 1 Prevalence and incidence of autoimmune hepatitis among different countries in the world1

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

We identified a total of 13 patients with coexisting HIV infection and AIH. All were Asians. There were 5 (38%) males and 8 (62%) females, with a median age of 40 years at AIH diagnosis (range: 26-61 years). The patients were referred to our liver clinic for evaluation of abnormal liver functions.

History of present illness

Most patients (11/13, 84.6%) presented with chronic persistent elevation of aminotransferase enzyme levels for a median duration of 10 mo (range: 4-31 mo). One patient presented with acute hepatitis for 2 mo, and the other patient presented with jaundice for a month.

History of past illness

The median duration of HIV infection before AIH diagnosis was 6 years (range: 1-24 years). Eleven patients received antiretroviral therapy once HIV infection was diagnosed. Only 2 patients were started on antiretroviral drugs 13 and 4 years after HIV diagnosis, respectively. Eight (62%) patients received only one antiretroviral regimen and had never been switched to other regimens until the time of AIH presentation: 6 and 2 patients received tenofovir/emtricitabine/efavirenz(TDF/FTC/EFV) and tenofovir/lamivudine/efavirenz (TDF/3TC/EFV), respectively.Another 5 (38%) patients were treated with multiple antiretroviral regimens prior to AIH diagnosis. The first patient who had HIV infection for 10 years received zidovudine/3TC/EFV for 2 years and was subsequently switched to TDF/3TC/EFV for 1 year and TDF/FTC/EFV since then. The second patient with HIV infection for 2 years was put on TDF/FTC/EFV for a brief period and switched to abacavir(ABC)/3TC/rilpivirine (RPV). The third patient with HIV infection for 1 year was initially on stavudine (d4T)/3TC/EFV but developed peripheral neuropathy at the second month; therefore, he was switched to TDF/3TC/EFV. The fourth patient who had HIV for 13 years was initially treated with TDF/3TC/EFV and switched to TDF/FTC/EFV. The last patient had HIV infection for 24 years; 13 years after diagnosis, she was started on d4T/3TC/nevirapine (NVP) for 4 years, followed by TDF/3TC/NVP for 3 years, and TDF/3TC/EFV since then. All patients had undetectable HIV viral loads at AIH presentation, with median CD4+ cell counts of 557 cells/x106L (range: 82-963 cells/× 106L).

Physical examination

Of the 13 patients, one (7.7%) had cirrhosis at the time of AIH presentation. She had signs of chronic liver diseases on examination and radiologic features of cirrhosis.

Laboratory examinations

Table 2 summarizes the baseline characteristics and laboratory data of the 13 patients at the time of AIH diagnosis. The median (range) levels of aspartate aminotransferase(AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) enzymes were 178 (63-393) and 177(49-353) U/mL, respectively (normal AST and ALT levels are < 35 and < 40 U/mL,respectively). Twelve patients had normal bilirubin levels, and one patient had elevated total bilirubin levels of 6.3 mg/dL. Notably, elevated globulin levels were observed in all patients (normal range: 2.0-3.3 g/dL).

Because viral hepatitis infection, including viral hepatitis A, B, C and E (HAV,HBV, HCV and HEV), is one of the common causes of abnormal liver chemistry,blood tests for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), antibody to HAV, HCV and HEV were performed. All 13 patients were tested for HBsAg and anti-HCV antibody. One patient was positive for HBsAg and another patient was positive for Anti-HCV antibody, however, both patients had undetectable HBV DNA and HCV RNA viral load at AIH presentation. There were 7 (54%) and 7 (54%) of patients who were tested for anti-HAV IgM and anti-HEV IgM antibody. All were negative for the tests.

Other blood tests to investigate the possible causes of abnormal liver chemistry included thyroid function test (n = 5), iron studies (n = 5), ceruloplasmin level (n = 1)and controlled attenuation parameter by FibroScan®(n = 7). The results were all negative.

Further diagnostic work-up

History of alcohol consumption as well as medication and herbal use was thoroughly reviewed to exclude alcoholic hepatitis and drug-induced liver injury as possible causes of abnormal liver chemistry. Further investigation revealed an elevation of immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels in 11 (85%) patients, with a median of 2,250 mg/dL(normal range: 7548-1768 mg/dL). Antinuclear antibody (ANA) was positive in 11(85%) patients; however, anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA) was positive in only 5(38%) patients.

Pathological examinations

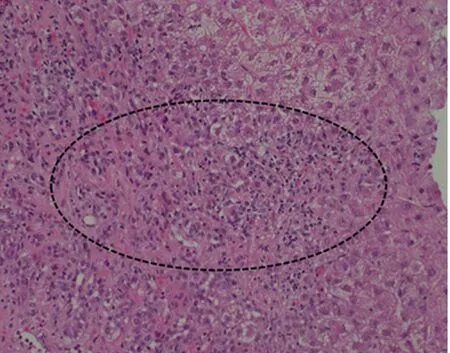

Liver biopsy was performed in all patients. They had histopathological findings compatible with AIH, i.e., lymphoplasmacytic cell infiltration and interface hepatitis(Figures 1 and 2). Three (23%) patients revealed cirrhosis on histopathological examination.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The final diagnosis of the presented cases was autoimmune hepatitis.

TREATMENT

After the diagnosis of AIH was made, 2 patients were referred back to the primary hospital for treatment initiation and long-term follow up, and 11 patients received treatment and were followed at our hospital. Ten of the 11 patients were started on prednisolone monotherapy for remission induction at daily doses of 40, 30 and 20 mg in 1, 5 and 3 patients, respectively. One patient who had Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis at presentation was put on a combination of low-dose prednisolone (15 mg/d) and azathioprine (25 mg/d).

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

?

Figure 1 Portal inflammation. A mononuclear cell inflammatory infiltrate in portal tracts (circle).

Liver chemistry was monitored every 2 wk during the first month after treatment initiation and every 1-4 mo afterwards depending on clinical outcome and the primary physician’s judgement. None of patients performed repeat liver biopsy. After 1 mo of therapy, all 11 patients showed improvement in liver chemistry. All 10 patients experienced liver enzyme normalization at a median time of 6 mo after immunosuppressive therapy initiation. The last patient who had received treatment for 4 mo had ALT improvement, but the ALT level remained slightly above the upper limit of normal at the time of writing this manuscript. After improvement of the liver chemistry, the dose of prednisolone was tapered, and azathioprine was added as lifelong maintenance therapy. One patient developed cytopenia from azathioprine, and was therefore placed on mycophenolate mofetil with a good response.

All 11 patients who received treatment at our hospital underwent regular follow-up visits. The median time to follow-up was 23 mo (range: 5-43 mo). During the followup period, one patient experienced a minor flare when the dose of steroid was tapered. At the time of AIH diagnosis, AST and ALT levels were 121 and 263 U/L,respectively, with IgG level of 2930 mg/dL. He was initially treated with prednisolone 30 mg/d for 2 wk, followed by 20 mg/d for 4 wk and 15 mg/d for 6 wk.Three months after treatment initiation, AST and ALT levels decreased to 50 and 93 U/L, respectively, with a declined level of IgG to 2130 mg/dL. Azathioprine 50 mg daily was therefore added with gradual reduction of prednisolone dosage to 10 mg, 5 and 2.5 mg/d during the next 7 mo period. At month 16 after therapy, AST and ALT levels increased to 71 and 100 U/L, respectively, with rising IgG of 2254 mg/dL.Prednisolone was therefore increased to 15 mg/d for 2 wk, followed by 10 mg/d for 10 wk, while the dose of azathioprine remained at 50 mg daily. Three months later,AST and ALT levels declined to normal limits (22 and 33 U/L) as well as IgG returned to normal level (1540 mg/dL). The patient was therefore prescribed a low dose prednisolone (5 mg daily) and azathioprine (50 mg daily) as a maintenance therapy to prevent relapse.

The immunosuppressive drugs had never been discontinued in all patients, thus,none of the patients had disease relapse, defined as ALT increases > 3 times the upper limit of normal. At the last follow-up visit, 10 patients were doing well with normalized ALT levels, and 1 patient remained in the induction phase. None experienced HIV viral rebound or infectious complications during treatment with immunosuppressive drugs. Table 3 displays the treatments and outcomes for each patient.

DISCUSSION

In this review, we present 13 cases with coexisting HIV infection and AIH. The diagnosis of AIH in HIV-infected patients is challenging and complex for a number of reasons. First, hepatitis in HIV-infected patients more commonly has other etiologies,particularly viral hepatitis B and C, adverse effects from antiretroviral or other drugs,opportunistic infection, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Second, the disease has a wide spectrum of clinical presentation, ranging from asymptomatic, hepatitis,cirrhosis to acute liver failure. Third, the natural history of AIH is dynamic.Transaminase enzyme levels are not always persistently elevated. Spontaneous remission or intermittent flares can occur, resulting in fluctuations of liver enzymes.Last, elevation of IgG and positivity of autoantibodies is a common phenomenon in HIV-infected individuals. HIV itself can cause elevation of IgG levels due to polyclonal stimulation of B cells[40-42]. The presence of autoantibodies has been reported in 45% of HIV-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy[41]. Given the difficulties in diagnosis, AIH in the setting of HIV infection is not a well-recognized condition and may be underdiagnosed, with only 38 cases reported in the literature (Table 4)[21-39].

Figure 2 lnterface hepatitis. Portal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate extending into the lobule (dashed line).

Due to the impaired immune status in HIV infection, autoimmune diseases in this context are counterintuitive. Nonetheless, accumulating evidence illustrates that autoimmune diseases can develop after HIV diagnosis. Two recent large epidemiologic studies described a list of autoimmune diseases that occurred in HIVinfected patients. A study of 5186 HIV-infected patients in France reported that 36 patients had coexisting autoimmune diseases, accounting for a prevalence of 0.69%.The most common autoimmune disease was immune thrombocytopenic purpura (n =15), followed by inflammatory myositis, sarcoidosis and Guillain-Barré syndrome (n =4 each). Autoimmune hepatitis was present in only 1 patient, accounting for the prevalence of AIH in HIV infection of 0.02%[35]. Another nationwide study of 20444 Taiwanese patients with HIV infection found that the most common autoimmune diseases were uveitis, psoriasis and inflammatory bowel diseases, with incidence rates per 100000 person-years of 104, 102 and 92, respectively[43]. Other autoimmune diseases frequently occurring in HIV-infected individuals include Sjögren syndrome,rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondyloarthritis, and autoimmune hemolytic anemia. The study did not find any HIV-infected patients with AIH.

The pathogenesis of AIH includes genetic predisposition, with a loss of tolerance against self-antigens, hyperreactivity of cytotoxic T cells and production of autoantibodies against liver antigens, leading to hepatocellular toxicity and damage[44]. Human leukocyte antigens have been identified as genetic risk factors of AIH. HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR4 are known to be susceptible genes in Caucasian and Japanese populations, respectively[18]. However, genetic polymorphisms as risk factors for AIH specifically for HIV populations haven’t yet been identified. Mechanisms by which AIH emerges in HIV infection remain poorly understood. In HIV infection,CD4 T-cells are affected and may lead to autoimmune diseases[45]. Another possible mechanism is B-cell dysfunction induced by chronic persistent HIV viremia[42].

In this report, 12 of 13 (92%) patients had CD4 counts over 300 cells/mm3, while only 1 patient had CD4 counts of 82 at the time of AIH diagnosis. This is in-line with the previous reports of 38 HIV cases with AIH showing a CD4 count over 250 cells/mm3in 89% of cases (Table 4). These findings suggest that AIH in the context of HIV infection more frequently occurs when the immune status has been restored.

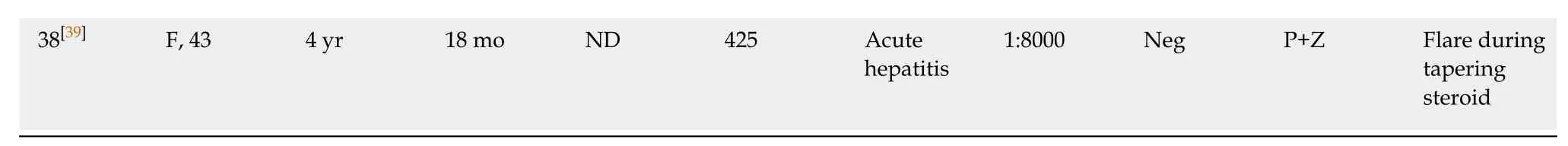

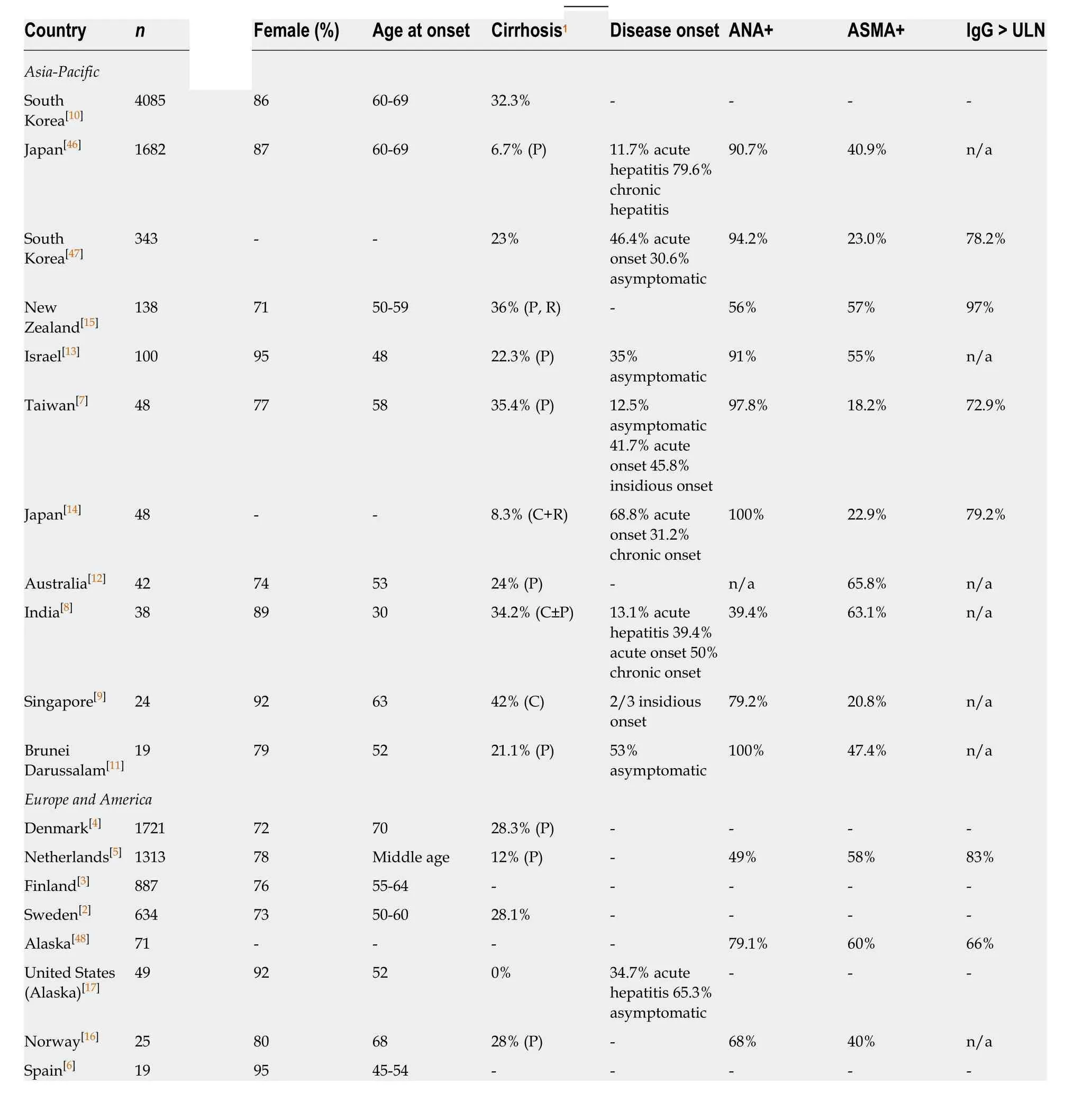

The demographic characteristics of AIH patients who have underlying HIV infection are slightly different from those of patients without HIV infection. In the non-HIV-infected population, AIH affects both sexes regardless of age and ethnicity.AIH more frequently occurs in females than in males. The proportion of affected females ranges from 70%-95% in both the Asia-Pacific region and Europe and America (Table 5)[2-17,46-48]. In patients with HIV infection and AIH, female predominance remains true but is less pronounced. The proportion of female patients was only 62% in the present study and was 71% in 38 previous reports (Table 4). In patients without HIV infection, AIH typically occurs in middle-aged populations,with an average peak onset from 50-70 years (Table 5)[2-17,46-48]. However, HIV-infected patients develop AIH at a younger age. The median age of our cohort was 40 years,with 46% and 85% developing AIH at an age less than 40 and 50 years, respectively.Similarly, for the 38 previously reported HIV-AIH patients, the median age was 43 years (range 21-70 years), among whom 38% and 75% younger than 40 and 50 years,respectively (Table 5).

Presentations of AIH vary greatly in both HIV- and non-HIV-infected patients. In non-HIV-infected patients with AIH, approximately 40% experience an acute onset,presenting with acute hepatitis or infrequently with jaundice. Approximately 30%-60% experience insidious onset or are asymptomatic (Table 5). Cirrhosis at AIH diagnosis is present in up to 40% of patients. HIV-infected patients who develop AIH have similar presentations to patients without HIV infection. Most patients (85%) in this case series had long-standing hepatitis, while only 15% experienced acute onset of the disease. Cirrhosis at the time of AIH diagnosis was present in 23% of our patients and 16% of the 38 previously reported cases.

Table 3 Treatment and outcome of autoimmune hepatitis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients

The diagnosis of AIH is established by criteria comprising clinical, laboratory and immunoserological parameters, liver histopathology, and exclusion of other causes of hepatitis. A diagnostic scoring system was first developed by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) in 1993 and subsequently revised in 1999.Both scoring systems are complex and not easy to use in real-world practice.Simplified diagnostic criteria were therefore proposed in 2008 and are now widely used (Table 6). With a cutoff of ≥ 6, the simplified scoring system has a sensitivity and specificity of 88% and 97% for the diagnosis of AIH. The specificity increases to 99%,with a decreased sensitivity to 81%, when a cutoff of ≥ 7 is used[49].

AIH is suspected in patients whose liver tests show transaminitis with elevated serum globulin levels. As shown in our HIV cohort, all patients have elevated globulin levels. Further investigation to support the diagnosis of AIH includes elevated serum IgG levels and the presence of circulating autoantibodies. Elevated IgG levels above the upper normal limit are observed in 70%-80% of non-HIV-infected cohorts (Table 6). Likewise, 11/13 (85%) of our HIV-infected patients with AIH had elevated IgG levels.

The presence of autoantibodies, including ANA, ASMA and anti-liver kidney microsome (LKM)-1, is a key laboratory feature of AIH. ANA is the most common autoantibody detected in AIH, with a prevalence of 80%-100% in most studies (Table 6). Among HIV-infected patients with AIH, the frequencies of ANA positivity were similar to those among non-HIV-infected patients, i.e., 11/13 (85%) and 27/38 (71%),in our cohort and in previously reported cases, respectively. It is important to note that ANA is not a specific autoantibody to AIH and can be found in other diseases,including nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and in healthy individuals[50-52]. Recent studies have reported that the prevalence of ANA positivity is 16% and 26% in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and in healthy individuals,respectively[50,52]. Anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA) is another common autoantibody detected in AIH. Although its prevalence is less than that of ANA, it is more specific to AIH[53]. The prevalence of ASMA positivity in AIH patients without HIV infection varies considerably, ranging from 18 to 66% (Table 5). The prevalence of ASMA positivity was relatively low in our HIV cohort, i.e., 5/13 (38%). This number was lower than that in the 38 previously reported patients with AIH and HIV, i.e.,24/35 (69%) (3 had missing data for ASMA). Although the presence of autoantibodiesis a diagnostic criterion, up to 17% of AIH patients are negative for ANA, ASMA and anti-LKM and are considered to have so-called “autoantibody-negative AIH”[54].

Table 4 Baseline characteristics at autoimmune hepatitis presentation of previously reported human immunodeficiency virus cases

ART: Antiretroviral therapy; B: Budesonide; M: Mycophenolate mofetil, P: Prednisolone; Z: Azathioprine; LT: Liver transplantation; NA: Not available.

Liver biopsy is essential to confirm the diagnosis and assess the severity of AIH.Interface hepatitis (plasma cell and lymphocyte infiltration at the interface of hepatic parenchyma and portal tract), emperipolesis and hepatic rosette formation are classic histopathological features, although not pathognomonic of AIH. Figures 1-4 display the histopathology of AIH in our HIV-infected patients. Although interface hepatitis is a common histological finding of AIH and is present in up to 87% of cases, it can be found in patients with viral hepatitis A/B/C/E infection and drug-induced hepatitis[55,56]. Emperipolesis and rosette formation are more specific features than interface hepatitis for the diagnosis of AIH and can be detected in 78% and 49% of AIH patients, respectively[55].

There are no treatment guidelines specifically for HIV-infected patients. Based on evidence from previous and the currently reported cases, HIV-infected patients with AIH can be treated in a similar fashion to non-HIV-infected patients.Immunosuppressive drugs are the mainstay of treatment. To prevent further hepatocellular damage and cirrhosis development, complete biochemical remission(normalization of serum aminotransferase and IgG levels) and histological remission must be achieved. Prednisolone monotherapy or combination therapy with azathioprine is the first-line treatment for the induction of disease remission, followed by maintenance therapy with azathioprine as a steroid-sparing medication.Prednisolone at the dose of 0.5-1 mg/kg/d, with the maximum dose of 60 mg/d, can be initially used as a single agent, followed by the addition of azathioprine 1-2 mg/kg/d when the liver chemistry shows improvement, with a decrease in prednisolone slowly until discontinued. A combination of prednisolone, at a maximum dose of 30 mg/d, and azathioprine at 1-2 mg/kg/d can also be used as induction therapy. Approximately 80%-90% of patients shortly experience improvement in symptoms and liver tests, usually within 2 wk, after treatment initiation. As suggested by a recent multicenter study in the Netherlands[57], life-long azathioprine is usually required for maintaining sustained remission and preventing disease relapse. In this study, the outcomes of 131 patients for whom immunosuppressive therapy was tapered after disease remission for at least 2 years were determined. It was found that after immunosuppressive drug was discontinued,47% of patients experienced disease relapse (i.e., elevation in ALT levels three times above the upper limit of normal), and 42% had a loss of remission (i.e., elevation in ALT levels that required retreatment). Retreatment was needed in approximately 60%, 70% and 80% of cases at 1, 2 and 3 years after drug withdrawal, respectively[57].

Treatment with immunosuppressive drugs improves the survival of AIH patients and decreases the 2-year mortality from 34% to 14%[58]. With proper treatment, AIH patients who do not have cirrhosis display comparable survival to the general population, while patients with cirrhosis have a higher mortality than the general population[59]. Frequent relapse or lack of disease remission increases liver-related mortality and liver transplantation[59].

CONCLUSION

In summary, this review highlights the fact that AIH should be included in the differential diagnosis of hepatitis in patients with HIV infection. To avoid delay in the diagnosis of AIH, elevation in IgG and presence of autoantibodies should be tested once common causes of hepatitis, particularly viral hepatitis, drug-induced liver injury and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, are ruled out. Liver biopsy should be further performed to confirm the diagnosis. Immunosuppressive therapy is safe and provides good outcomes in HIV-infected patients. After treatment, most patients experience rapid improvements in liver chemistry, followed by disease remission. However,long-term maintenance with low-dose immunosuppressive drugs is generally required to prevent disease relapse.

Table 5 Demographics of non-human immunodeficiency virus infected patients with autoimmune hepatitis

Figure 3 Shows lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate in hepatic lobule, i.e., lobular inflammation, and emperipolesis (circle).

Figure 4 Hepatocellular rosette formation (circle).

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- How does Helicobacter pylori cause gastric cancer through connexins: An opinion review

- Colorectal cancer: Parametric evaluation of morphological,functional and molecular tomographic imaging

- Sarcopenia and cognitive impairment in liver cirrhosis: A viewpoint on the clinical impact of minimal hepatic encephalopathy

- Significance of tumor-infiltrating immunocytes for predicting prognosis of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma

- Long non-coding RNA highly up-regulated in liver cancer promotes exosome secretion

- Circular RNA PIP5K1A promotes colon cancer development through inhibiting miR-1273a