Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio effectively predicts survival outcome of patients with obstructive colorectal cancer

2019-09-13XianQiangChenChaoRongXuePingHouBingQiangLinJunRongZhang

Xian-Qiang Chen, Chao-Rong Xue, Ping Hou, Bing-Qiang Lin, Jun-Rong Zhang

Abstract

Key words: Inflammation indexes; Emergency surgery; Self-expanding metal stent insertion as a bridge to surgery; Obstructive colorectal cancers

INTRODUCTION

Although several studies have been implemented in the screening for colorectal cancer, approximately 8%-29% of patients are diagnosed with obstructive colorectal cancer (OCC) as the first symptom[1,2]. Emergency surgery (ES) with or without stoma construction and self-expandable metal stent (SEMS) insertion as a bridge to surgery(BTS) are the current methods for OCC[3]. A BTS is preferred for symptomatic OCC due to effective decompression, better preoperative nutritional preparation, an improvement in the immunological reaction, and a lower incidence of stoma creation[4,5]. However, the enhancement of tumor dissemination and early recurrence reported by some studies hinder the usage of a self-expandable metal stent in OCC[6,7].Despite this, there is still no common consensus. Several predictive models on the prognostic outcome of OCC, including ASA, age, Duck's stage, and prognostic nutritional index, have been established[8,9], but few focus on the inflammation index[10].

The inflammatory response plays a dual role in the development of a tumor. On one hand, a chronic inflammatory response triggers the local accumulation of monocytes, platelets, and neutrophils, which secrete cytokines and inflammatory factors to induce tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. On the other hand, increasing monocytes and lymphatic cells would enhance the resistance against tumor invasion[11]. Increasing evidence shows that an elevated neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is closely related to a poor prognosis in ovarian cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, and elective colorectal cancer (CRC)[12-14]. The overexpression of circulating derived NLR, an effective biomarker for the diagnosis of early pancreatic cancer[15],was accompanied by increasing distal organ invasion in metastatic CRC[16]. An elevated preoperative lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR), as a superior existing biomarker, was positively correlated with the survival outcomes of patients with resectable CRC and presented better overall survival[17]. Other inflammatory indexes,such as the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR)[14]and systemic immune inflammation index (SII)[18], have also been studied in the exploration of optimal predictive models for tumor recurrence.

Different from the acute inflammatory response in patients undergoing ES, the alleviation of bowel obstruction after successful SEMS insertion in patients undergoing BTS would elicit a better immunological reaction and nutritional support,which might change the predictive factors for prognosis between the two groups.Preoperative inflammation indexes might favor patient selection and the establishment of a valid predictive model for the prognosis of OCC. In this study, we compared different inflammation indexes and other clinicopathological factors to evaluate the potential indications for ES and BTS for OCC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient population

All patients (n = 128) who underwent surgery for OCC at the Department of Emergency Surgery of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital from January 2008 to October 2015 were included in this study. Data from the patients' records were retrospectively collected and evaluated. The Institutional Review Board of Fujian Medical Union Hospital approved the study protocol. All patients provided informed consent for surgery. Patients were divided into an ES group and a BTS group based on the grade of bowel obstruction and families' choices. For incomplete obstruction,ES was preferred as the first choice. For complete obstruction, once patients who refused to accept SEMS insertion or failed in SEMS insertion, they would accept ES with intraoperative decompression.

Classification criteria

Patients who manifested with bowel obstruction were enrolled in this study. All diagnoses of OCC were confirmed by both emergency abdominal computed tomography (CT) and a pathological examination. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients who rejected surgery or were diagnosed with acute peritonitis or perforation; (2) Patients with severe infection, hematological diseases, or an immunological deficit; and (3) Patients who received preoperative adjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or immunotherapy.

Surgical protocols

For left-side OCC, we performed intraoperative lavage or manual decompression for better bowel preparation, and these protocols have been previously depicted. For right-side OCC, radical dissection with one-stage anastomosis was performed[19].

SEMS with BTS

Stent insertion was performed by an endoscopist who had experienced over 400 endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedures. Bridge to elective surgery was performed, once the stent was so successfully inserted that the intestinal obstruction completely relieved. Otherwise, ES was immediately performed.

Definition of variants

The neutrophil, lymphocyte, monocyte, and platelet counts from the peripheral blood tests and the inflammation indexes dependent on these factors were performed before surgery (e.g., NLR, dNLR, LMR, PLR, and SII) and stent insertion (e.g., NLR-pre,dNLR-pre, LMR-pre, PLR-pre, and SII-pre). The methods for the calculation of NLR,dNLR, LMR, and PLR have been described in previous studies[13]. The SII was calculated as (platelet count × neutrophil count)/lymphocyte count[18]. The cutoff point and the area under the curve (AUC) value of each inflammation index for the prediction of OS and DFS were determined with X-tile 3.6.1 software (Yale University,New Haven, CT, United States)[20]. According to the cutoff point, patients were divided into low-ratio and high-ratio groups for further analysis.

According to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual (7th edition)[21], we classified the tumor pathological stage. Comorbidities were defined as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and single and multiple organ dysfunction. The degree of obstructive symptoms was divided into five grades,termed as The ColoRectal Obstruction Scoring System (CROSS)[22]. According to the Clavien-Dindo classification system[23,24], we classified the perioperative complications into five grades.

Statistical analysis

Qualitative variables were compared by the χ2test or Fisher's exact test, and quantitative variables were compared via t-tests. Through Kaplan-Meier analysis, the 3-year OS and 3-year DFS were calculated. A Cox proportional hazards regression model was built to identify the independent risk factors for 3-year DFS and 3-year OS.Stratification analysis was used to compare the differences between subgroups. All Pvalues less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses and graphs were generated using SPSS 23.0 software.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

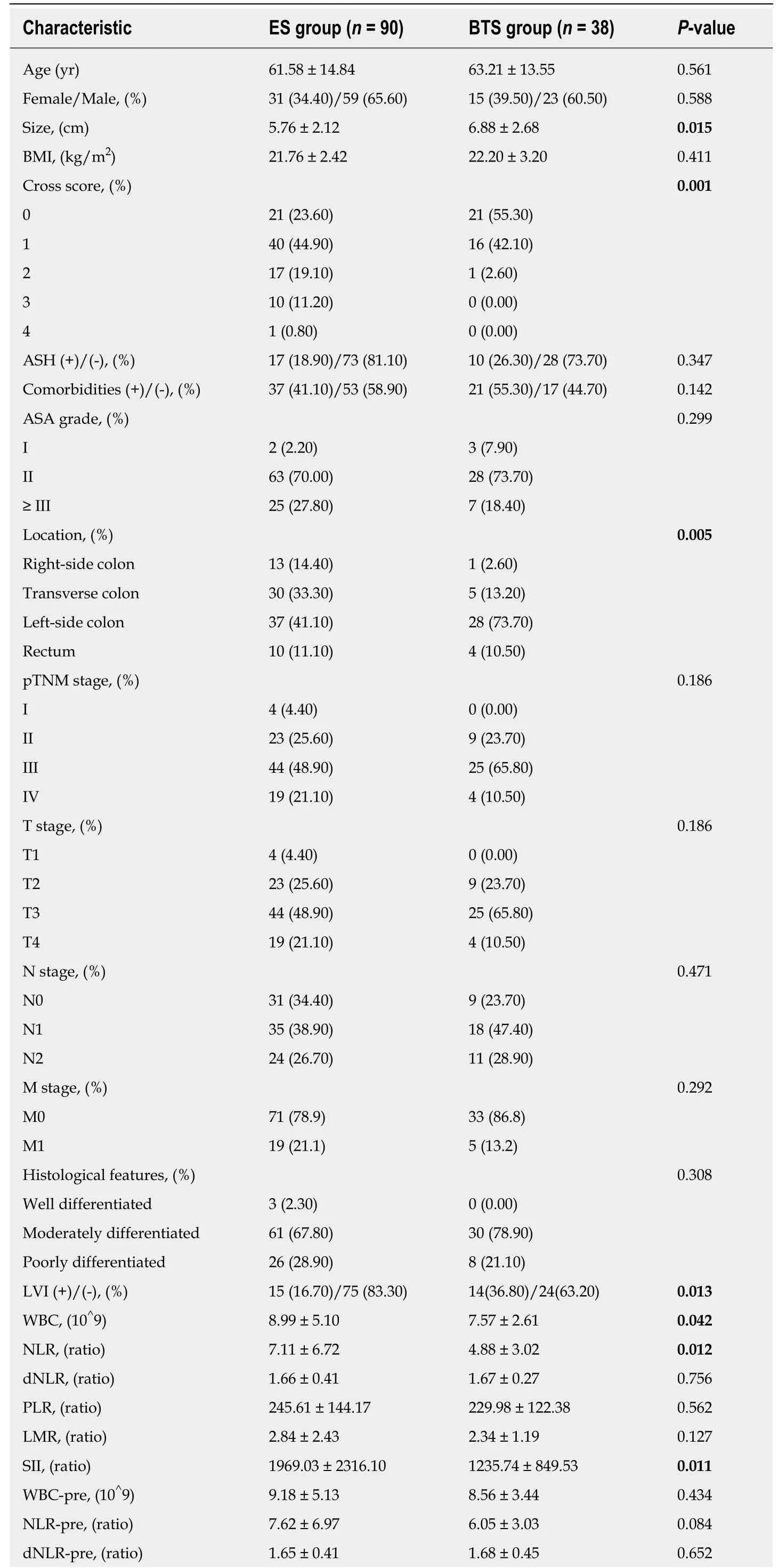

There were 128 patients enrolled in this study, who were divided into an ES group (n= 90) and a BTS group (n = 38), with similar age and sex ratios between the groups (P> 0.05). The average tumor size was 6.88 ± 2.68 cm in the BTS group, with a higher proportion of tumors located on the left side of the colon (73.70% vs 41.10%, P =0.005), and was much larger than the tumor size in the ES group (5.76 ± 2.12 cm, P =0.015). Moreover, the obstructive symptoms were more severe in the BTS group than in the ES group (Grade 0-I, 97.40% vs 68.50%, P = 0.001), as presented in Table 1. The remaining characteristic factors, including BMI, abdominal surgery history,comorbidities, ASA grade, pTNM stage, histological features, and the ratio of chemotherapy were similar between the ES and BTS groups (P > 0.05).

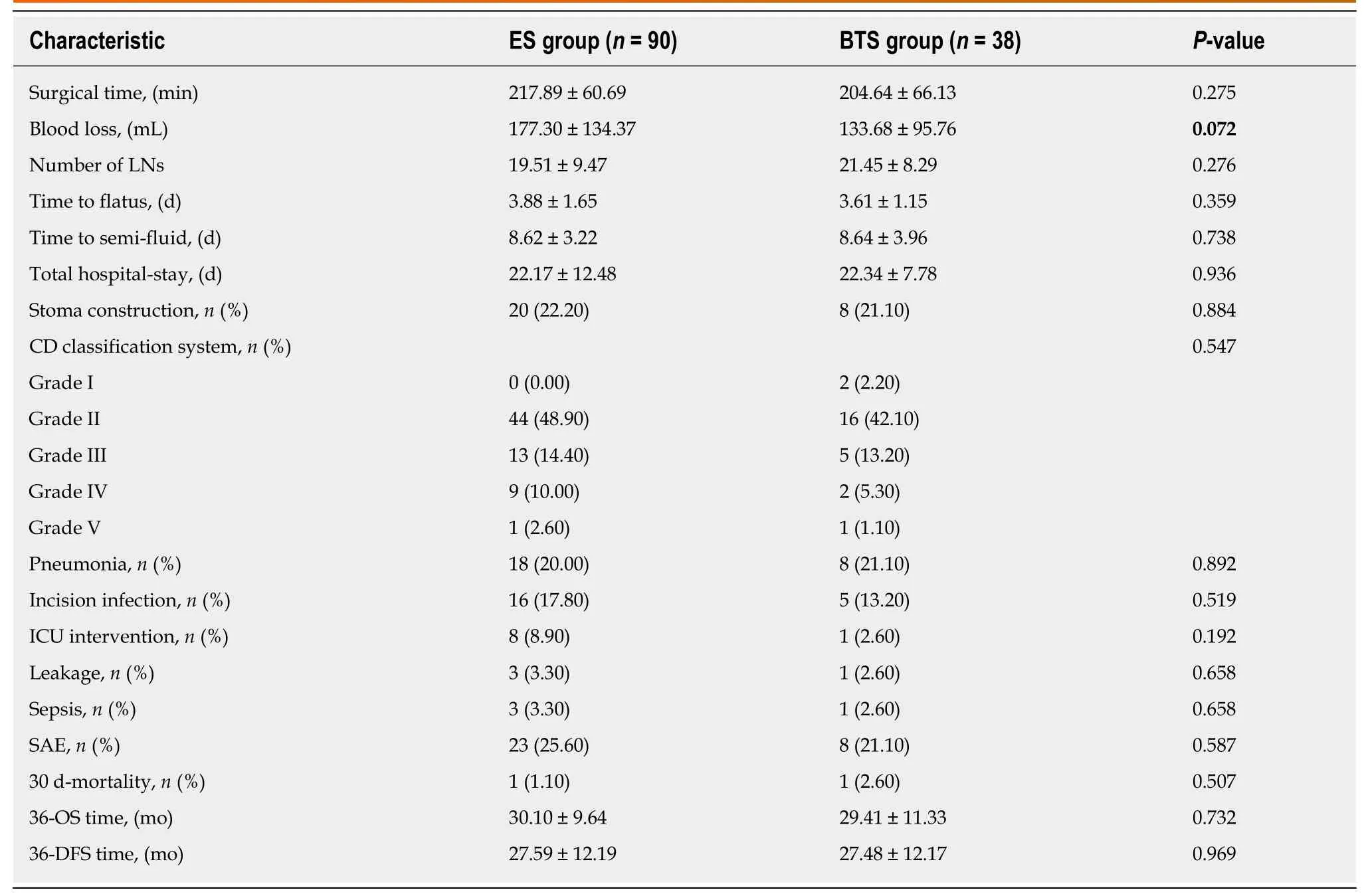

Outcome comparison between the ES and BTS groups

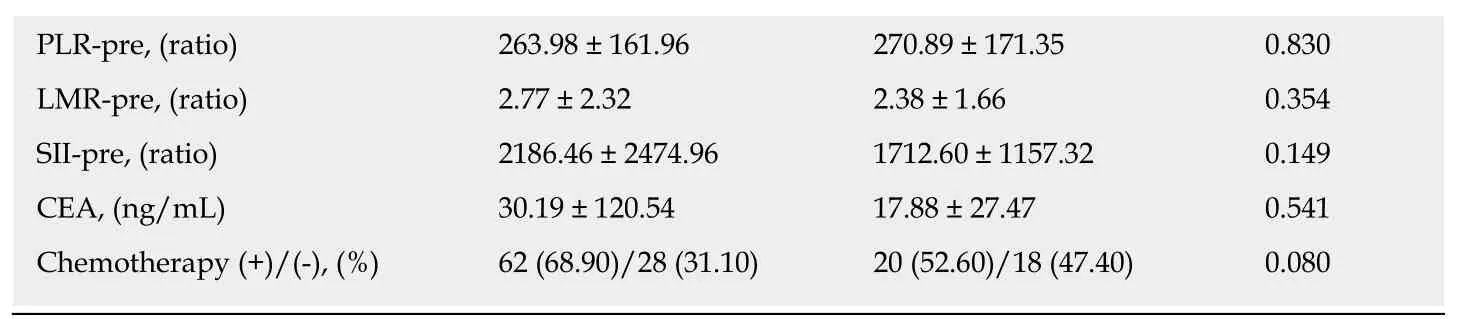

The blood loss in the BTS group was lower than that in the ES group (133.68 ± 95.76 mL vs 177.30 ± 134.37 mL, P = 0.072), with similar gastrointestinal recovery and postoperative complications (P > 0.05) (Table 2). Analogical survival outcomes including 3-year OS (30.10 ± 9.64 mo vs 29.41 ± 11.33 mo, P = 0.732) and 3-year DFS(27.59 ± 12.19 mo vs 27.48 12.17 mo, P = 0.969) were compared between the ES and BTS groups, and are plotted in Figure 1.

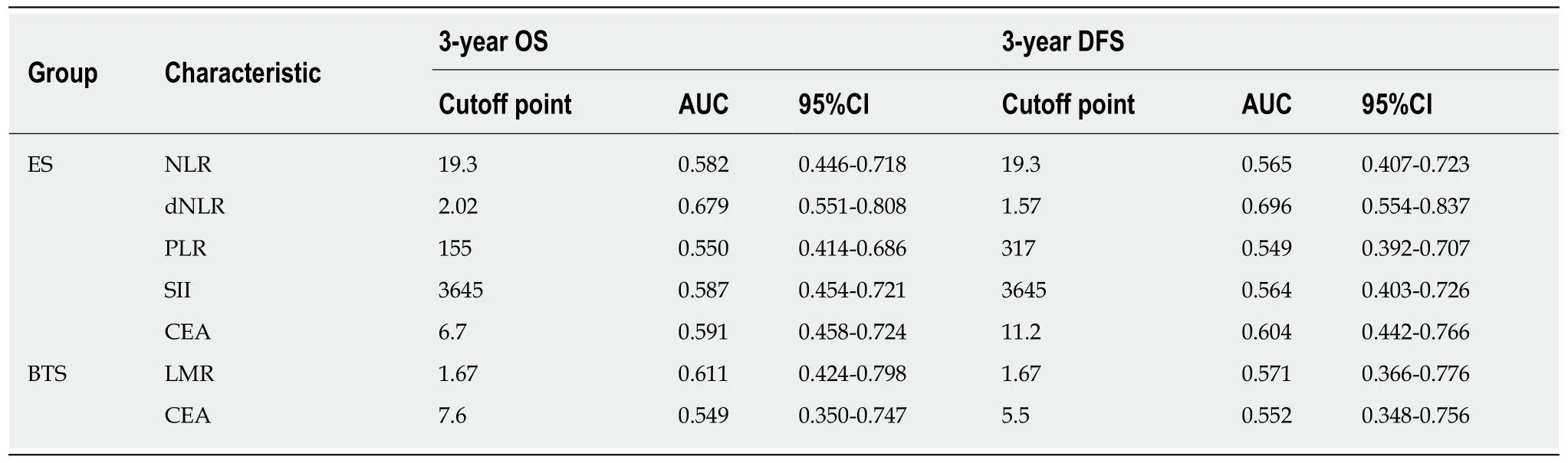

Predictive values and cutoff points of different inflammation indexes

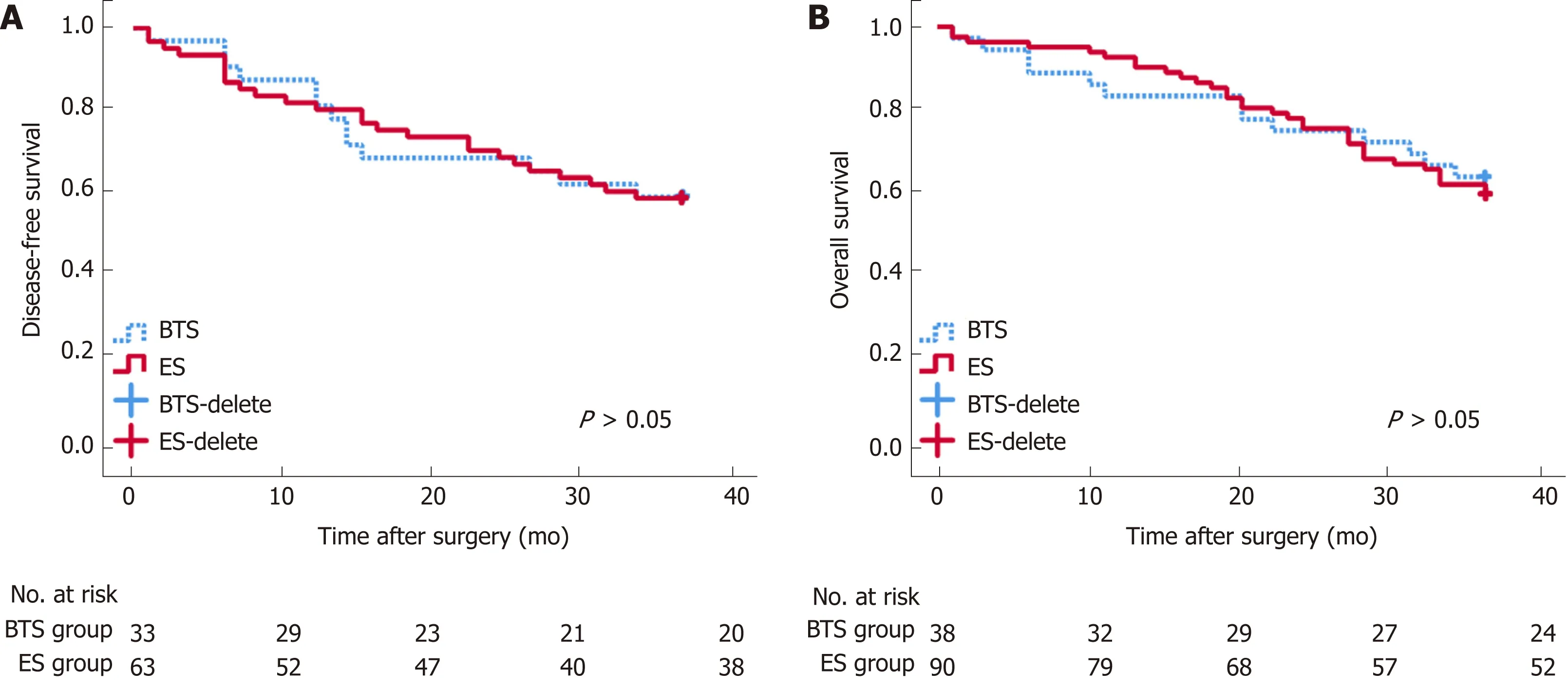

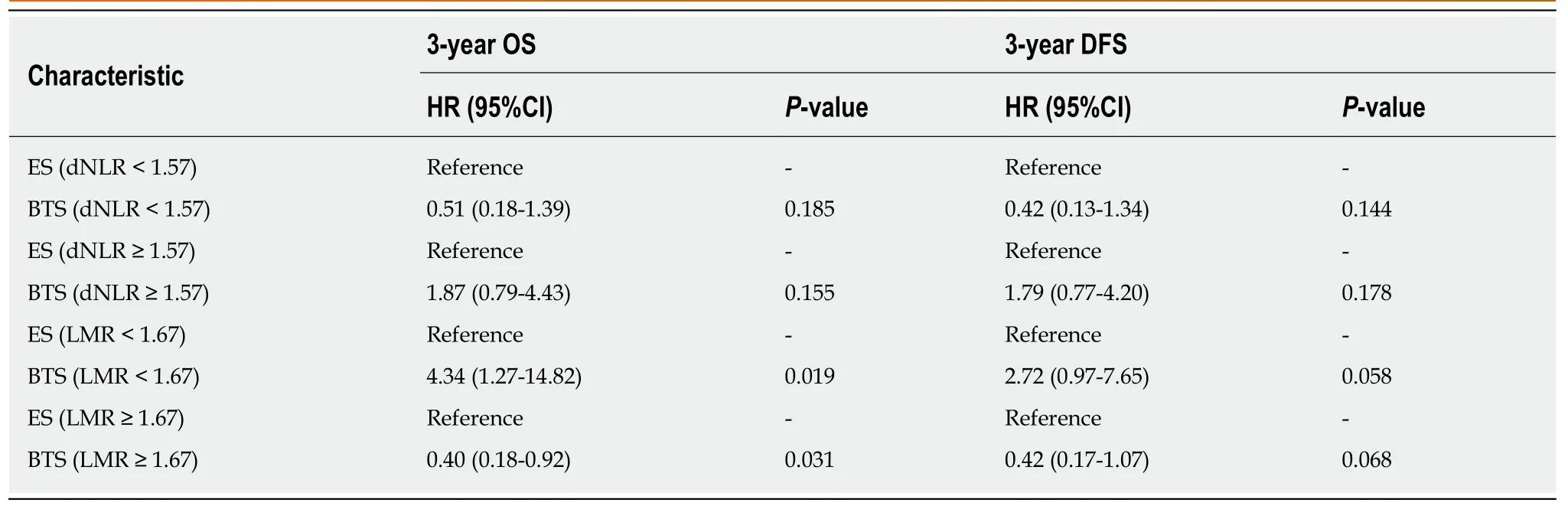

A decreasing tendency was observed for WBC (8.56 × 109± 3.44 × 109), NLR (4.88 ±3.02), and SII (1235.74 ± 849.53) in the BTS group after SEMS insertion, compared with the WBC (7.57 × 109± 2.61 × 109), NLR (6.05 ± 3.03), and SII (1712.60 ± 1157. 32) before SEMS insertion (P < 0.05), as presented in Table 1. Different inflammation indexes were analyzed between the ES and BTS groups. As a result, dNLR was preferred as a prognostic biomarker for the ES group since it had the highest AUC for 3-year OS(0.679, 95%CI: 0.551-0.808) and 3-year DFS (0.679, 95%CI: 0.551-0.808); the cutoff point value was 1.57. Conversely, based on the highest AUC for 3-year OS (0.611, 95%CI:0.424-0.798) and 3-year DFS (0.571, 95%CI: 0.366-0.776), the LMR was recommended as a prognostic biomarker for the BTS group, with 1.67 as its cutoff point. These data are depicted in Table 3 and plotted in Figure 2.

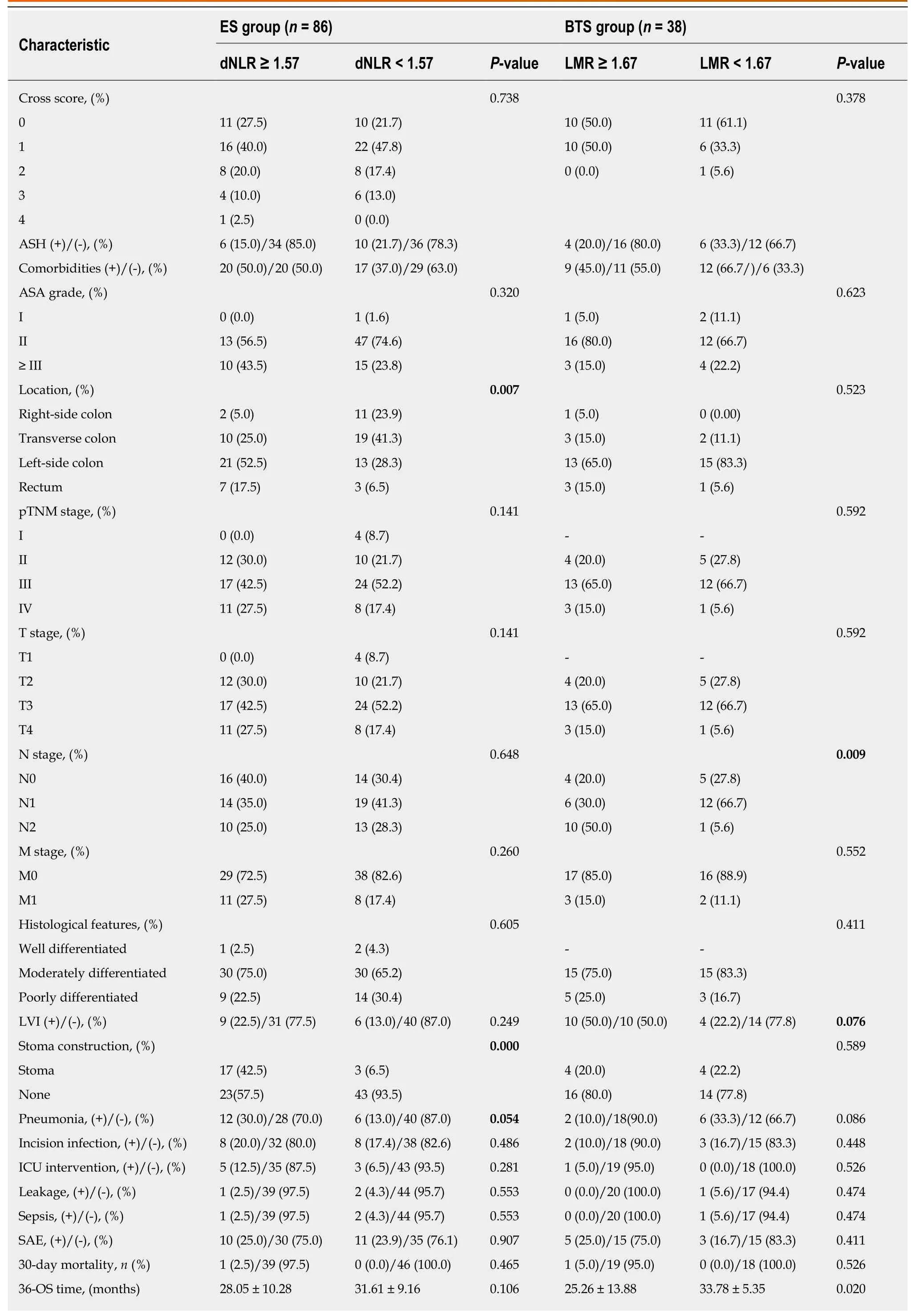

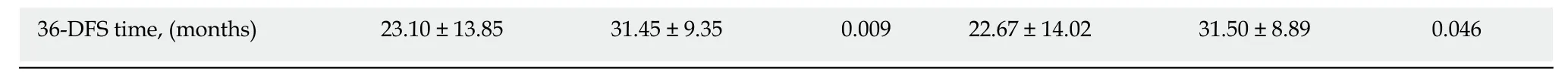

Clinical evaluation of different inflammation indexes

In Table 4, patients were divided into high-ratio and low-ratio grades based on the dNLR in the ES group and the LMR in the BTS group. A high-ratio grade of dNLR (≥1.57) was closely related to a higher proportion of tumors located on the left side of the colon and rectum (P = 0.007), and a higher incidence of stoma construction (P =0.001) and postoperative pneumonia (P = 0.054), with a lower 3-year DFS (dNLR ≥1.57: 23.10 ± 13.85 mo vs dNLR < 1.57: 31.45 ± 9.35 mo, P = 0.009) in the ES group.Separately, a high-ratio grade of the LMR (≥ 1.67) in the BTS group showed more advanced lymphovascular metastasis (P = 0.072) and lymph node invasion (P = 0.009),with a lower 3-year OS (LMR ≥ 1.67: 25.26 ± 13.88 mo vs LMR < 1.67: 33.78 ± 5.35 mo,P = 0.020) and 3-year DFS (LMR ≥ 1.67: 22.67 ± 14.02 mo vs LMR < 1.67: 31.50 ± 8.89 mo, P = 0.046). The dNLR was the only independent risk factor in the ES group both for 3-year OS (HR = 2.34, 95%CI: 1.08-5.07, P = 0.032) and 3-year DFS (HR = 3.02,95%CI: 1.23-7.42, P = 0.016). In contrast, the status of LVI (HR = 3.52, 95%CI: 1.03-12.02, P = 0.045) and the LMR (HR = 4.57, 95%CI: 0.98-21.38, P = 0.053) significantly affected the 3-year OS in the BTS group. Only the LMR was an independent risk factor for 3-year DFS (HR = 3.11, 95%CI: 1.13-8.54, P = 0.052) in the BTS group, as shown in Tables 5 and 6 and Figure 2.

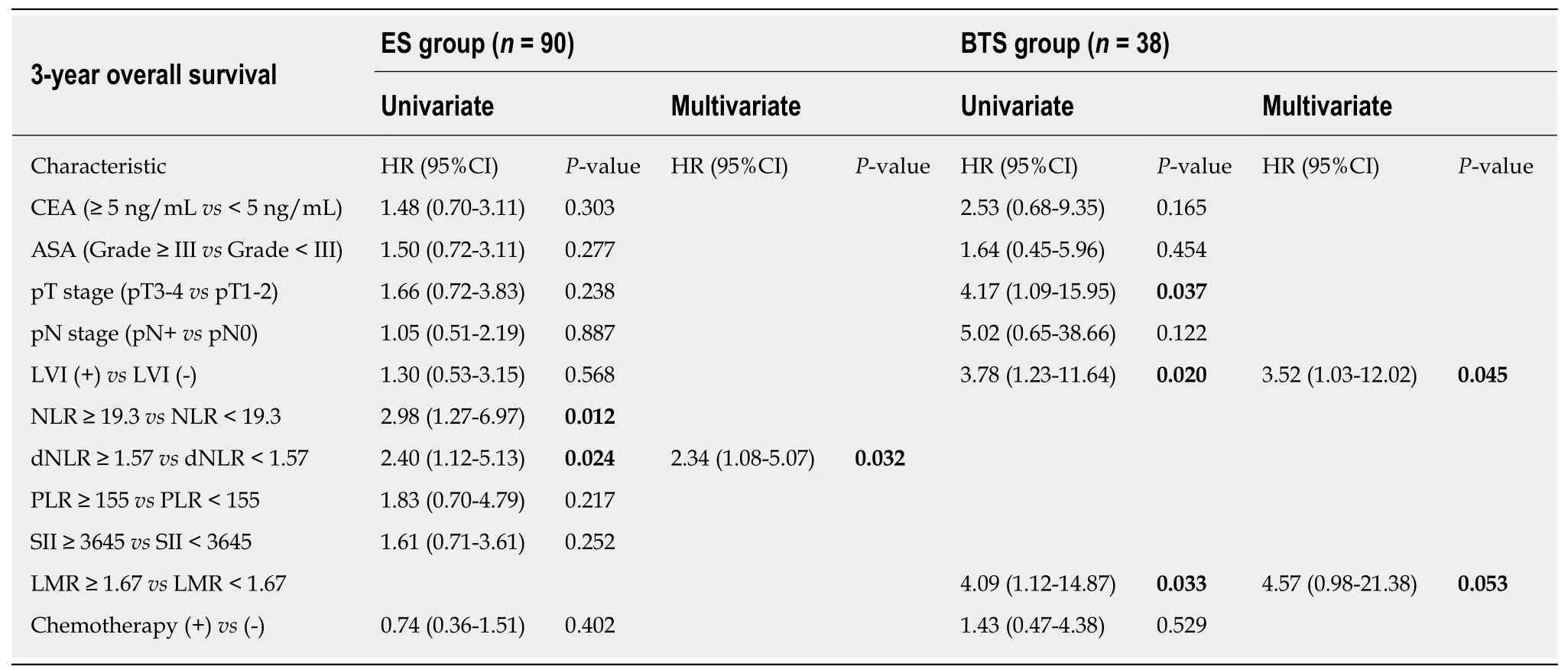

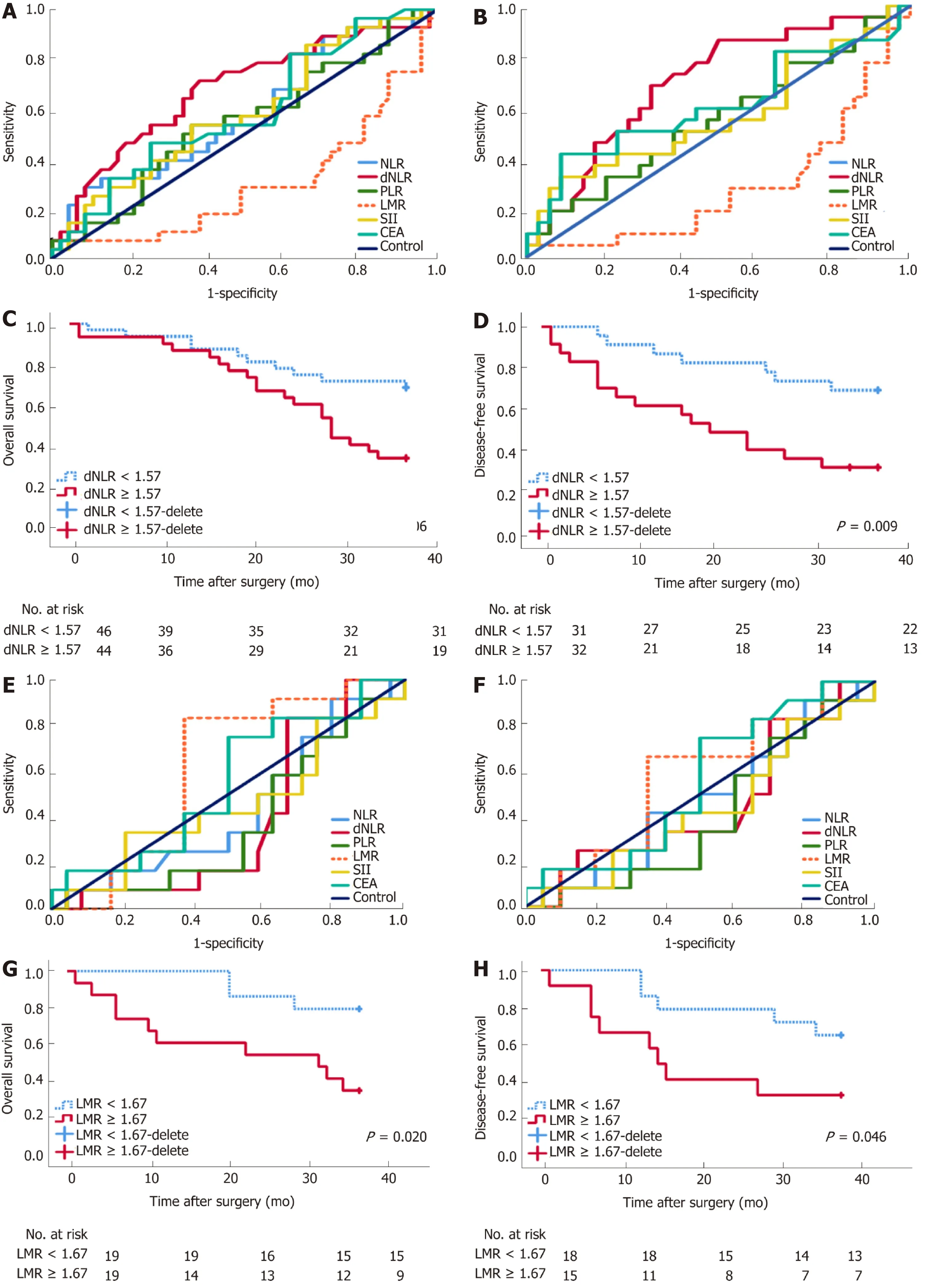

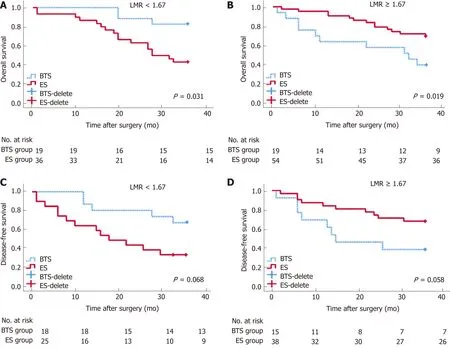

Selective choices based on inflammatory biomarkers

By stratification analysis of 3-year OS and 3-year DFS in different grades of dNLR and LMR, we revealed that only the LMR obviously differentiated the oncological and survival outcomes between the ES and BTS groups. A lower LMR (<1.67), as a protective factor, indicated a lower rate of death (HR = 0.40, 95%CI: 0.18-0.92, P =0.031) and tumor recurrence (HR = 0.42, 95%CI: 0.17-1.07, P = 0.068) in the BTS group.Conversely, a higher LMR (≥1.67), as a risk factor, showed a higher proportion ofdeath (HR = 4.32, 95%CI: 1.27-14.82, P = 0.019) and tumor recurrence (HR = 2.72,95%CI: 0.97-7.65, P = 0.058) in the BTS group; these data are presented in Table 7 and Figure 3.

Table 1 Comparison of clinicopathological characteristics between emergency surgery and bridge to surgery groups

SEMS: Self-expanding metal stents; BTS: Bridge to surgery; ASH: Abdominal surgery history; WBC: White blood cells; dNLR: Derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR: Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; SII: Systemic immune inflammation index; LMR: Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio; Cross: Colorectal obstruction scoring system; LVI: Lymphovascular invasion. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

OCC is always accompanied by a severe local and systemic inflammatory response;some reasons, including the overgrowth of intestinal bacteria, their translocation through the distended colonic wall, and, moreover, septic shock, have been recognized. In this study, we found that the cutoff point for the NLR of 19.30 was much higher than that in elective CRC[14,24], supporting the existing severe systemic inflammation. Although ES and BTS via SEMS insertion have been widely performed,there is still not an objective indication for either. Weighing the balance between oncological outcomes and better preoperative nutritional support with the alleviation of systemic inflammation, BTS via SEMS insertion is only recommended for symptomatic and high surgical risk groups, especially left-side OCC, by the ESGE and World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES)[1,3]. In this study, analogous with a previous study[25], the BTS group had a higher proportion of LVI (36.80%), though similar 3-year OS and 3-year DFS were observed between the ES and BTS groups. A decreasing tendency in the WBC, NLR, and SII levels was observed after SEMS insertion, which might explain the reason why different inflammation indexes were concluded from the ES (dNLR) and BTS (LMR) groups in our study.

Since 1970, a decreasing peripheral lymphocyte count has been recorded in advanced colon cancer[26], and the inflammation index has been investigated in several kinds of cancer, as it is cost-effective and convenient. The dysbiosis and outgrowth of intestinal microbial species, as a result of acute bowel obstruction and distention,triggers systemic inflammation, leading to the accumulation of neutrophils and monocytes that secrete cytokines and chemokines with the induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen intermediates (RNI), which might aggravate colonic injury and DNA damage[11]. OCC almost coexists with immunosuppression, which causes a deficiency in adaptive immunologic cells such as T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes, which play important roles in immune surveillance and pathogen depletion[27]. The mechanical stress of SEMS and chronic ablation to the colonic wall enhances local platelet adhesion and the mediation of tumor invasion into lymphovascular vessels[28], which was supported in the current study by a higher proportion of LVI in the BTS group. In this study, we compared different inflammation indexes, including the NLR, dNLR, PLR, LMR and SII, with the CEA level in terms of the predictive value for the prognosis between the ES and BTS groups. Finally, the dNLR was defined as the most efficient index in the ES group; a high dNLR (≥ 1.57) was closely related to low survival benefits, a high incidence of stoma construction, and postoperative pneumonia. Dissimilarly, the LMR was defined as the most efficient index in the BTS group; a high LMR (≥ 1.67) was closely related to low survival benefits and a high incidence of LVI and lymph node invasion.

The reason why different predictive models for the ES and BTS groups were observed in OCC is still unknown. This might be owing to the hypothesis that, as a result of bacterial outgrowth and translocation, OCC always has a severe systemic inflammatory response and immunological deficit, and for patients with a high surgical risk, a BTS via SEMS insertion is preferred. In this study, we found that the BTS group had more severe obstructive symptoms and a bigger tumor size than the ES group. Sufficient alleviation of bowel distention and preoperative nutritional support would improve systemic inflammation and enhance the immunological reaction in the BTS group. However, the mechanical stress of the metal stent might aggravate the local inflammatory response[29-31]and enhance tumor invasion. In our study, with the dramatic decrease of the systemic inflammatory response in the BTS group, the dNLR could not determine the benefit group for ES or BTS. Only the LMR could serve as an objective biomarker for the indication for OCC. A low LMR (< 1.67)was correlated with a low incidence of death and tumor recurrence in the BTS group.Conversely, a high LMR (≥ 1.67) showed a high proportion of death and tumor recurrence in the BTS group, and was preferred for ES.

Figure 1 Long-term survival analysis between emergency surgery and bridge to surgery groups. Disease-free survival (DFS, A) and overall survival (OS, B)after surgery seemed similar between the bridge to surgery (BTS) and emergency surgery (ES) groups.

There were some limitations existing in this study. First, this was a retrospective study in a single center; thus, we will initiate a prospective, multicenter study to confirm our findings. Second, the sample size was not so large that more patients are needed in future research. Furthermore, this study just analyzed the ratio of immune cell populations in the peripheral blood, instead of systematic immune responses including the production of cytokines or expression of PD-1 or CTLA-4. More efforts should be made on the investigation of immune responses occurring in the systemic circulation or tumor.

In conclusion, this study suggests a similar survival and oncological benefits for BTS and ES in patients with OCC. Even though different inflammation indexes for prediction of the prognosis were observed between the ES and BTS groups, they could serve as effective biomarkers. The dNLR was closely related to the prognosis in the ES group, while the LMR was closely related to the prognosis in the BTS group.Specifically, as the potential benefit group, patients with a low LMR might be preferred for BTS via SEMS insertion.

Table 2 Comparison of short-term and long-term outcomes between emergency surgery and bridge to surgery groups

Table 3 Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis of long-term survival of emergency surgery and bridge to surgery groups

Table 4 Comparison of clinicopathological features between high-ratio and low-ratio grades in both emergency surgery and bridge to surgery groups

SEMS: Self-expanding metal stents; BTS: Bridge to surgery; Cross: Colorectal obstruction scoring system; ASH: Abdominal surgery history; dNLR: Derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR: Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; SII: Systemic immune inflammation index; LMR: Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio; LVI:Lymphovascular invasion; OS: Overall survival; DFS: Disease-free survival; ICU: Intense care unit; SAE: Severe adverse effects. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

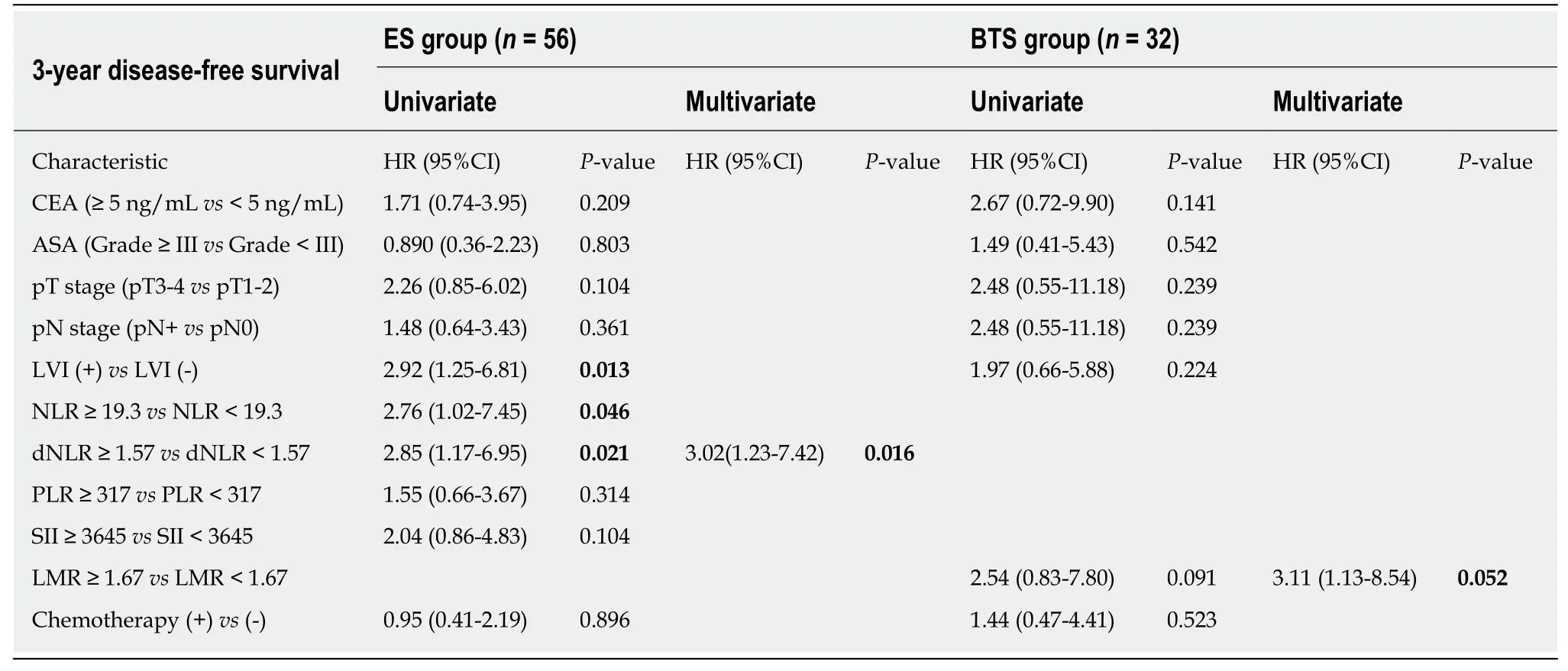

Table 5 Univariate and multivariate analyses of risk factors for survival outcomes in both emergency surgery and bridge to surgery groups

Table 6 Univariate and multivariate analyses of risk factors for oncological outcomes in both emergency surgery and bridge to surgery groups

Table 7 Stratification analysis of oncological and survival outcomes between high-ratio and low-ratio grades in both emergency surgery and bridge to surgery groups

Figure 2 Receiver operating characteristic curve and long-term survival analysis of emergency surgery and bridge to surgery group. Derived neutrophil-tolymphocyte ratio (dNLR) is preferred as a prognostic biomarker for the emergency surgery (ES) group with the highest area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) for 3-year overall survival (OS) (0.679, 95%CI: 0.551-0.808) (A) and 3-year disease-free survival (DFS) (0.679, 95%CI: 0.551-0.808) (B), with a cutoff point value of 1.57. High-ratio grade of dNLR (≥ 1.57) was closely related to lower 3-year DFS (≥ 1.57 vs <1.57, 23.10 ± 13.85 mo vs 31.45 ± 9.35 mo, P = 0.009) in the ES group (D), but not with 3-year OS (C). Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR) was preferred as a prognostic biomarker for bridge to surgery (BTS) group with the highest AUC for 3-year OS (0.611, 95%CI: 0.424-0.798) (E) and 3-year DFS (0.571, 95%CI: 0.366-0.776) (F), with a cutoff point value of 1.67. High-ratio grade of LMR (≥ 1.67) was closely related to lower 3-year OS (≥ 1.67 vs <1.67, 23.10 ± 13.85 mo vs 33.78 ± 5.35 mo, P = 0.020) (G) and 3-year DFS (≥ 1.67 vs < 1.67, 22.67± 14.02 mo vs 31.50 ± 8.89 mo, P = 0.046) in the BTS group (H).

Figure 3 Analysis of 3-year overall survival and 3-year disease-free survival, by different lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratios between emergency surgery and bridge to surgery groups.P < 0.05 (log-rank test). Low lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR) (LMR < 1.67) indicated higher rates of 3-year OS (A) (HR = 0.40,95%CI: 0.18-0.92, P = 0.031) and 3-year disease-free survival (DFS) (C) (HR = 0.42, 95%CI: 0.17-1.07, P = 0.068) in the bridge to surgery (BTS) group. Conversely,high LMR (LMR ≥ 1.67) showed lower proportions of 3-year OS (B) (HR = 4.32, 95%CI: 1.27-14.82, P = 0.019) and 3-year DFS (D) (HR = 2.72, 95%CI: 0.97-7.65, P =0.058) in the BTS group.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

operating characteristic curve analysis showed dNLR as the optimal biomarker for the prediction of DFS in ES, by contrast, LMR was recommended for BTS with regard to OS and DFS. dNLR was related to stoma construction, postoperative pneumonia, and DFS in the ES group. LMR was closely related to lymph nodes invasion, OS, and DFS in the BTS group. LMR could differentiate OS between the ES and BTS groups. A low LMR (< 1.67) was correlated with a low incidence of death and tumor recurrence in the BTS group.

Research conclusions

As a supplement for the latest ESGE guidelines, the indications for the use of SEMSs in OCC might elaborate to patients with low preoperative LMR, who would benefit from BTS via SEMS insertion.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Role of NLRP3 inflammasome in inflammatory bowel diseases

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease, obesity and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: The burning questions

- Intestinal permeability in the pathogenesis of liver damage: From non-alcoholic fatty liver disease to liver transplantation

- Crosstalk network among multiple inflammatory mediators in liver fibrosis

- Neoadjuvant radiotherapy for rectal cancer management

- Helicobacter pylori virulence genes