The Division of Labor Amid Economic Globalization

2019-04-09ByWangHaifeng

By Wang Haifeng

T he global division of labor is the natural result of industrial development in an open world economy. This outcome leads to industrial transfers-- or shifts and greater efficiency, though this process accompanied by painful economic restructuring. Economic reorganization allows multinational corporations to allocate resources on a global scale, maximize their profits and keep investment and operational risks at the lowest possible level.

The speed and extent of globalization has been hastened by a combination of factors including trade liberalization, investment facilitation,financial internationalization and even information technology.New corporate heavyweights have emerged and joined the ranks of older multinationals. These companies have been able to take advantage of their dominant position in value chains, supply chains and technological innovation. They play a crucial role in determining the pattern of the global division of labor of the future.

New Features of Globalization

Since the financial crisis, the joint efforts of scientific and technological innovation as well as industrial and structural reform have brought new features to economic globalization.New patterns in the global industrial division of labor and industrial transfer have emerged as a result.

Asia has become the most active region for international industrial transfers. Since the financial crisis,economic dynamism has shifted from developed economies to a joint effort between developed and developing economies.

The drawbacks of globalization –job losses, stagnant wages and other economic dislocations -- have jolted some segments of the advanced economies such as the United States,Europe and Japan, and this has affected the political landscape. In the US, the Trump administration has loudly proclaimed its policy of“America first” – even at the expense of Washington’s closest allies.This has provoked trade frictions and inflicted serious damage to the framework of global economic governance. The UK has similarly turned to populism as the answer to its economic and social ills. Today,it is still grappling with the complex reality of its Brexit vote – an electoral choice that has dealt a stinging blow to European integration.

Meanwhile, Japan continues to see friction in its trade and political relations with South Korea. By contrast, China, India and ASEAN,have become positive forces for globalization, and they continue to improve their business environment through internal reforms.

According to the World Bank’s Business Environment Report 2020 released in October 2019, Asian economies - Singapore, China’s Hong Kong, South Korea and China’s Taiwan -- ranked second, third,fifth and 15th, respectively, in terms of providing a conducive place for business development. New Zealand led the pack but Australia and Japan were 14th and 29th, respectively.China ranked 31st though it had the most significant improvement in its business environment.

A new round of division of labor for global industry and international industrial transfer is also concentrated in East Asia, Southeast Asia and South Asia. The World Investment Report 2019, released by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development in June,shows that despite a sharp contraction in global cross-border investmentover the past three years, developing Asian economies have continued to attract foreign investment at record levels, accounting for 39.5% of global foreign investment in 2018.

Table 1 Changes in the flow and stock of foreign capital utilized in developing economies in Asia (billions of dollars)

There also is considerable room for Asian economies to benefit from further industrial transfers.Currently, opposition to globalization from developed economies reflects dissatisfaction with the distribution of globalization’s benefits. In fact, these economies have been the leaders of globalization in the past, with the highest levels of openness. These economies also hope that dynamic developing economies in Asia will open their markets further.

According to World Trade Organization statistics, the US, Japan and Europe had commitments to attain average tariffs of 3.45%, 4.74%and 5.1%, respectively, in 2018. Their actual tariff levels were close to the targets at 3.45%, 4.36% and 5.23%.For Switzerland and Singapore, their committed tariff levels in 2018 were 8.21% and 9.54%, and their actual tariff levels were 6.61% and 0.02%.

In contrast, China, Vietnam,South Korea, Indonesia and India committed to meeting tariff levels of 10%, 11.9%, 16.48%, 37.13% and 50.8%, respectively. Their actual tarifflevels came in lower than their target at 7.5%, 9.51%, 13.73%, 8.06% and 17.14%, respectively. Nonetheless,compared with developed economies,Asia’s developing economies still lagged far behind in terms of the degree of openness. Their potential for utilizing foreign capital and undertaking international industrial transfers remains huge.

Although growth has been particularly noticeable in China, the average profit margin of the nation’s Fortune 500 companies in 2019 was only 5.3%, which was significantly lower than the 7.7% for US corporations and the global average of 6.6%. China’s 9.9% average return on equity was markedly lower than the 15% in the US and the global average of 12.1%.

China's Changing Global Position

Since joining the WTO nearly two decades ago, China has changed from a passive receiver of industrial trends to an important force in the international division of labor and industrial transfers. It has been constantly bringing new vitality to the global economy and has become a foundation for economic prosperity and stability in Asia.

China has long been a popular destination for cross-border investment and industrial transfers.As the largest developing economy,China has stable institutional policies, a huge market, high levels of consumer demand, and reliable infrastructure. These advantages,coupled with continuous economic vitality unleashed by the reform and opening program, have made Chinaa hot destination for cross-border investment.

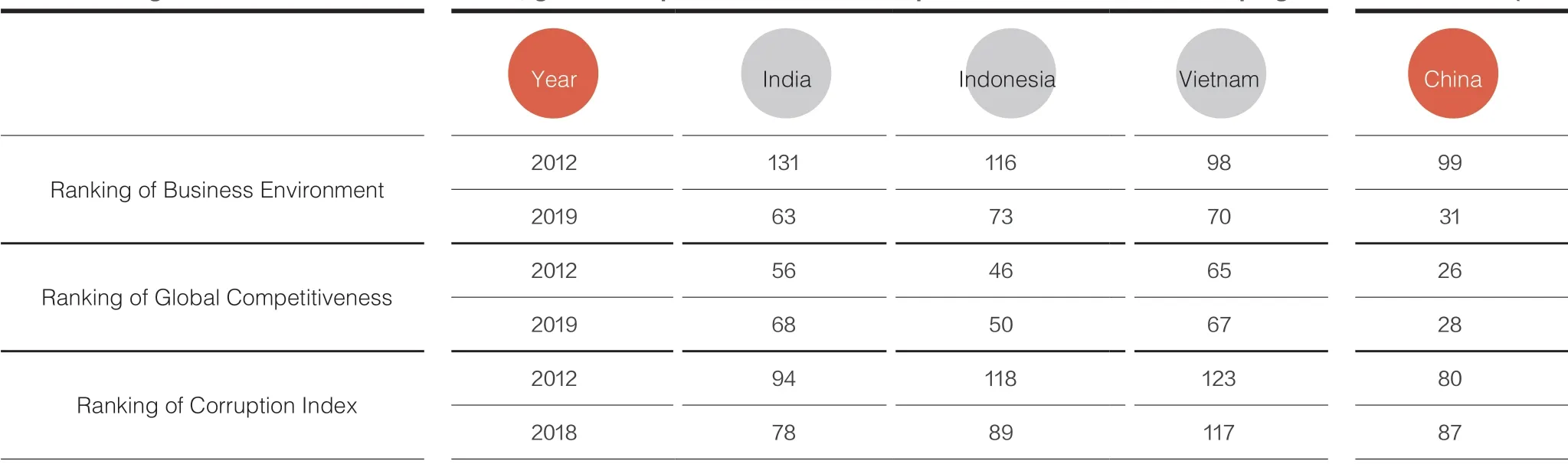

Table 2 Changes in the business environment, global competitiveness and corruption index in certain developing economies in Asia (ranking)

As a result of the US Federal Reserve’s monetary policy adjustments and the Trump administration’s tax cuts, global cross-border investment contracted sharply for the third year in a row in 2018. Investment fell from US$2.0 trillion in 2015 to US$1.3 trillion in 2018. The decline in 2018 from the previous year was 13%.

Despite the global contraction in investment, China’s actual foreign direct investment rose 3% to US$139 billion in 2018. Statistics from the Ministry of Commerce show that in the first three quarters of 2019,China actually absorbed US$100.87 billion in foreign investment, with a year-on-year growth of 2.9%. Hightech industries accounted for 30% of the total, climbing 35%. According to World Investment Report, China has been the largest recipient of foreign investment among developing countries for 27 consecutive years.

China continues to strengthen its capacity to participate in the global division of labor. Reform policies have been steadily improving the nation’s business environment, and competition – as well as cooperation– with foreign companies has helped Chinese enterprises grow rapidly.Moreover, their ability to innovate has been significantly strengthened.

In 2012, there were 79 Chinese enterprises in the Fortune 500,including six from Taiwan. China ranked second that year, but still had a significant gap with the United States with 132.

A total of 129 Chinese companies,including 20 private companies and 10 Taiwanese companies, made the ranks of the Fortune 500 in 2019,surpassing the 121 companies in the US for the first time. The share of high-tech products in China’s overall exports increased from 29.3% in 2012 to 30.1% in 2018. China’s nonfinancial outbound direct investment increased from $77.2 billion in 2012 to US$120.5 billion in 2018. Nonfinancial outbound investment grew by 3.8% year on year in the first three quarters of 2019. The private sector has also become a mainstay of China’s foreign trade. Companies such as Huawei, Xiaomi, Tencent and Alibaba have become among the most dynamic and innovative private companies in the Fortune 500.

High Quality Development

China has seen a re-balancing of its international balance of payments.The payments surplus – as a proportion of China’s GDP – dropped from 2.5% in 2012 to 0.4% in 2018.The proportion rose slightly to 1.3%in the first half of 2019, but that was still within a reasonable range.Germany, for example, was 7.3%while Japan was 3.5%.

Consumption has also become the core driver of China's economic growth. Investment boosted China’s economic growth by 3.4 percentage points in 2012, while consumption contributed 4.3 percentage points with a contribution rate of 54.9%. The gap in 2018 widened, with investment accounting for 2.1 percentage points of economic growth and 5.0 percentage points – or 76.2% of economic growth from consumption.During the first three quarters of 2019, consumption continued to be the core driving force for China’s economic growth with a contribution rate of 60.5%.

A more flexible exchange rate also played a role in China’s economic development.

The service sector has been leading China’s economic growth. In 2012,secondary industry boosted China's economic growth by 3.9 percentage points, while the service sector accounted for 3.5 percentage points– or 45% of growth. In 2018, the contribution of the service sector rose to 59.7% and reached 60.6% over the first three quarters of 2019.

A more flexible exchange rate also played a role in China’s economic development. The renminbi exchange rate, now more market-based, not only confounded critics who accused China of manipulating its exchange rate, but also punished speculators who bet against it. China’s economic fundamentals has already made the renminbi the most robust currency on the global foreign exchange market since 2012. In turn, its longterm stability and increased market flexibility further strengthened the international community’s confidence in China’s economy.

India, Indonesia and Vietnam

Economic reforms of developing Asian economies such as India,Vietnam and Indonesia over the past 30 years have gradually turned their late-mover advantages into actual competitive advantages. This has allowed them to participate in economic cooperation and industrial division of labor in Asia as well.This has not only promoted the development of their domestic manufacturing, but also led to the rapid growth of the local economy.Nevertheless, they may also face a series of challenges.

The ability of India, Vietnam and Indonesia to attract investment has improved significantly in recent years, but compared to China,these economies still lag far behind.Since 2015, against a background of three consecutive years of sharp contraction in global foreign capital utilization, Indonesia and Vietnam have maintained rapid growth in foreign capital utilization, while India encountered a slight contraction. Yet,in both flow and stock, there still is a large gap between these economies and China (see table 1). In 2018,China's stock of utilized foreign capital was about $1.63 trillion,which was 1.88 times that of India,1.41 times Indonesia and 2.54 times Vietnam. Vietnam has grown rapidly in foreign capital utilization in the last two years, but it is still far short of the other economies in this group.

Foreign investment in Vietnam,Indonesia and India mainly comes from Asian countries, while China’s investment stock in these countries is relatively small. In recent years,Vietnam’s foreign investment has primarily come from Japan followed by South Korea, Singapore and China.Half of its foreign capital utilization was concentrated in processing and manufacturing industries.Chinese investment accounts for only 4% of Vietnam’s total foreign investment stock. Foreign investment in Indonesia mainly came from Singapore, Japan, China, China’s Hong Kong and Korea, among which China’s investment stock represents less than 5% of the total. Foreign investments in India are largely from countries such as Mauritius,Singapore, the United Kingdom,Japan and the United States. China accounts for less than 1% of India’s total foreign investment stock.

While the market environment in India, Vietnam and Indonesia has improved significantly in recent years, these countries still rank low in international competitiveness due to serious corruption problems and other social issues. According to the survey of the World Bank and the World Economic Forum on the business environment of developing economies in Asia, India,Vietnam and Indonesia improved their business environment ranking from 131, 98 and 116 in 2012 to 63, 70 and 73 respectively in 2019.But their global competitiveness rankings, which were 56, 65 and 46, respectively, in 2012, fell to 68,67 and 50 in 2019. Widespread corruption also greatly affected their ability to take advantage of industrial transfers (see table 2).