终止怀疑:丧尸、吸血鬼、外星人、机器人……以及女高音?

2019-03-23司马勤KenSmith编译李正欣

文:司马勤(Ken Smith) 编译:李正欣

我必须承认,阅读玛丽·金特尔(Mary Gentle)长达680页的“另类历史小说”《邪恶歌剧》(Black Opera)令我心驰神往。故事围绕着一位活在19世纪意大利那不勒斯的英国编剧,他接到费迪南大帝的委约,撰写一部超凡的新歌剧,目的是为了对抗一部由秘密组织制作的、为了引动维苏威火山爆发并乘机将魔鬼召唤到人间的“邪恶歌剧”。

新的“正义歌剧”背后显然有着更具戏剧性的故事:这位英国编剧的合作伙伴是一位意大利贵族兼业余作曲家,而这位贵族作曲家的现任妻子与编剧曾有过长达一年的恋情。她更是位女高音,也是这部“正义歌剧”的女主角。内容那么精彩,小说肯定可以大卖,对吧?事实上,一切听起来都富有歌剧性,直至我们发现这位女高音的真正身份是——丧尸(zombie)。

是的,一只丧尸。

当小说从“另类历史”跳进“奇幻恐怖”故事后,叙事性随即一落千丈。一位书评家甚至质疑,这部包括“火山、丧尸、鬼魂、三角恋、秘密组织、天主教廷、易装癖,就连拿破仑都来客串了一小段”的小说,怎么会如此异常地缺乏张力。

上:桑姆托·苏恰里故小说《吸血鬼合流》封面

左:玛丽·金特尔的小说《邪恶歌剧》封面

也许作者不应把拿破仑拉进来。但这部小说却令我想起一个问题:歌剧剧目里,究竟有多少作品的主题与丧尸——或鬼魂、食尸鬼、吸血鬼——混在一起?安妮·赖斯(Anne Rice)于1976年发表的《夜访吸血鬼》(Interview with a Vampire)让恐怖小说摇身一变为畅销文学。几年之后,她撰写的新小说,书名为《呼天唤地》(Cry to Heaven),可这部“歌剧”小说发生在18世纪,以阉伶歌手为主人公,一个吸血鬼的鬼影都找不到。

也不奇怪,你会在科幻小说的子流派“太空歌剧”①编者注:“太空歌剧”(Space Opera)一词,是在20世纪40年代被发明出来专门称呼科幻文学中某一类特定小说的。这类小说的背景通常是庞大的银河帝国或繁复的异星文化,情节混合了动作和冒险,是地道的宇宙英雄罗曼史。在“太空歌剧”电影里,太空只是冒险的场所,现有的科学常识并不是限制人们想象力的枷锁。里找到许多女高音吗?正如西部片被贬为“马戏”(horse opera),或者通常由清洁剂公司赞助的日间情景电视剧被称为“肥皂剧”(soap opera)一样,严肃的读者们不会把那些讲述关于战争、浪漫与漫游太空的煽情故事放在眼里。《飞侠哥顿》(Flash Gordon)?《星球大战》(Star Wars)?你可以想象那些高傲的、拥护“正统分类”的人嘲笑道:“它们不过是‘太空歌剧’罢了。”

要想在“太空歌剧”里找到真正说女高音的故事,你必须认真地找——差不多要把整个书架翻遍。安妮·麦卡弗里(Anne McCaffrey)与赖斯齐名:正如赖斯让大家更深入了解吸血鬼一样,麦卡弗里让喜欢巨龙的读者们雀跃不已。麦卡弗里的《水晶歌唱家》(Crystal Singer)三部曲的主角,是一位潦倒的歌剧女高音,她在水晶矿场找到一份冒险性很高的差事,利用自己的绝对音高来控制重机器。菲利普·迪克(Philip K.Dick)的一部后世界末日科幻小说《机器人会梦见电子羊吗?》(Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?)讲述了一位旧金山的赏金猎手,他营生的伎俩,就是抓捕假装是人类的机器人(android)。他走进歌剧院,深信舞台上的女高音是个机器人。为什么?他太熟悉克丽斯塔·路德维希(Christa Ludwig,德国女中音歌唱家)唱片里的那首咏叹调,但这个机器人唱起来感情不够投入。[这部1968年出版的小说,到了1982年拍摄为电影《银翼杀手》(Blade Runner)。导演把背景移至洛杉矶,歌剧女高音改为脱衣舞女郎,这些都是时代变迁的象征。]

左页:影片《第五元素》中全身蓝皮肤的外星人女高音演绎《拉美莫尔的露琪亚》中悲伤的咏叹调

让我们重返吸血鬼这个主题。创作出最令人满意且带有歌剧题材的魔幻小说家,应该是桑姆托·苏恰里故(Somtow Sucharitkul)。在他还未创办曼谷歌剧院之前,这位作曲家兼指挥家也涉足文坛,用S.P. Somtow这个笔名以各种散文体裁写作。他的小说《吸血鬼合流》(Vampire Junction)里有一名12岁的摇滚歌手,其实是活了两千年的吸血鬼。他的死对头是一位年迈的指挥家,一听到男孩唱歌,就认出这个几十年前曾经参加过试唱的嗓音。

虽然桑姆托创作《吸血鬼合流》的时间比赖斯的《夜访吸血鬼》要早得多,但他的小说直到1980年代中期才有机会面世。尽管这部小说最终被恐怖小说作者协会(Horror Writers Association)列为“40本最佳恐怖小说”之一,出版商一直以来都认为故事过分怪诞——也许过分暴力,会让毫无戒备之心的读者感到不安[写作风格将恐怖电影的视觉效果与音乐视频的节奏相匹配,这个文学流派被称为“喷血朋克”(splatterpunk)]。不过说真的,我认为无法广为流传的障碍是那些歌剧常识。

几年前,看罢他在曼谷制作的《莱茵的黄金》后,我跟桑姆托提出疑问:他是否真的认为钟情恐怖小说的读者们能看得懂《魔笛》与《蓝胡子公爵的城堡》中的暗喻吗?或者他们知晓吸血鬼匿藏的巢穴被熊熊烈火烧毁的情景,其实是向《众神的黄昏》致敬吗?他调皮地说:“不,仅有2%或3%看得懂的人会觉得这很酷。”

不过,在我们完全摒弃这些电影之前,我必须推荐一下法国导演吕克·贝松(Luc Besson)的《第五元素》(The Fifth Element)。尽管这部影片符合大多数人对“太空歌剧”的定义,但电影里有实实在在的歌唱家演唱歌剧。穿上礼服的布鲁斯·威利斯(Bruce Willis)聆听一个全身蓝皮肤的外星人女高音,以一连串超越人类可以掌握的发声技巧,将《拉美莫尔的露琪亚》(Lucia di Lammermoor)中悲伤的咏叹调演绎得尤为动人。这是整部电影中最令人难忘的一刻。

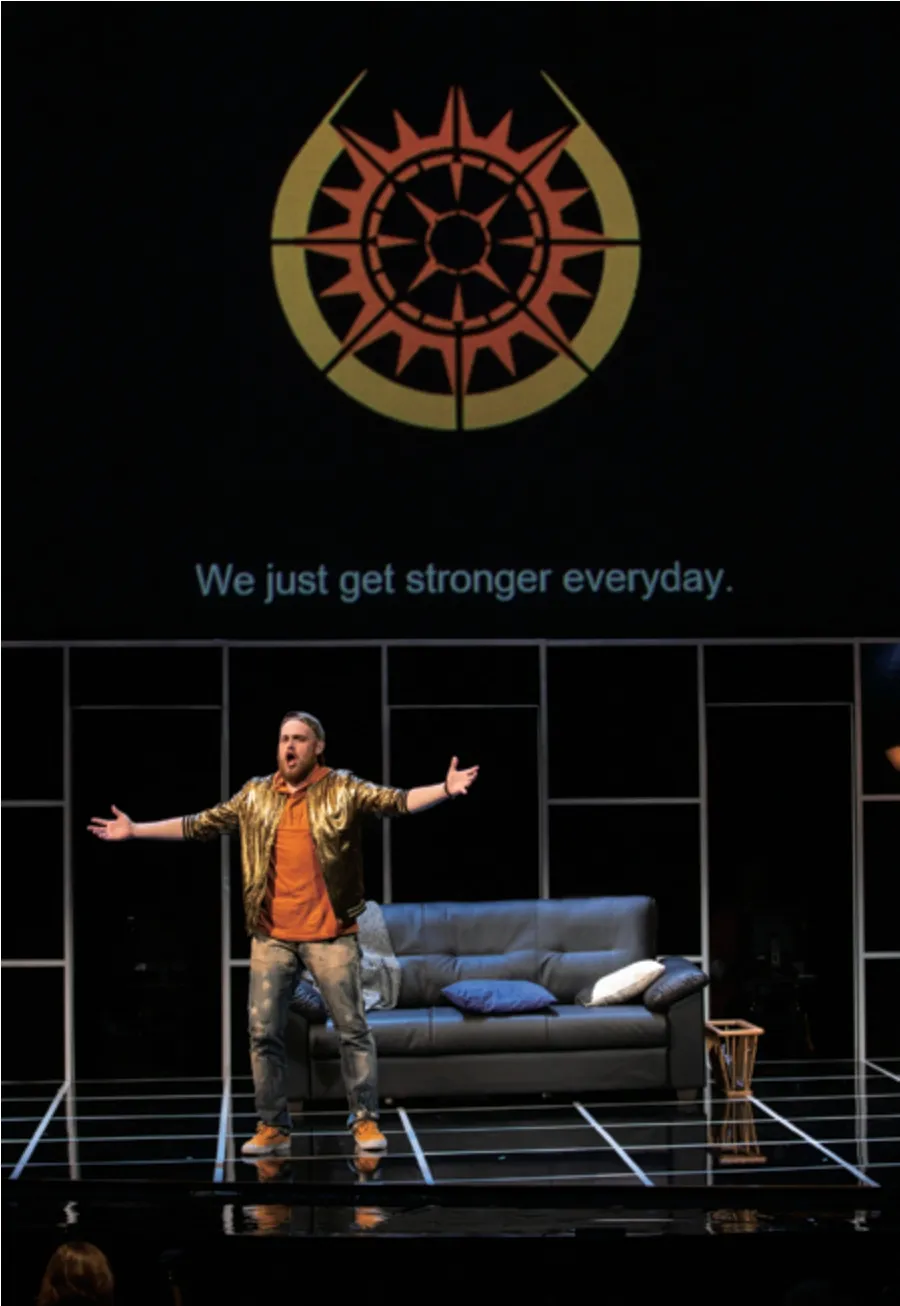

正当我在思量着,这个精彩片段在地球上某个角落还在回响时,我听到了关于《永久死亡》(PermaDeath)这部歌剧。该剧被誉为世界上第一部“电子游戏歌剧”(videogame opera),去年9月世界首演时,每位观众可以通过手机App参与其中。《永久死亡》由丹·维斯康提(Dan Visconti)作曲,编剧林晓英(Cerise Lim Jacobs)的创作灵感源自她儿子普莱特·爱普斯坦(Pirate Epstein)。当林女士问“海盗”,什么可以让他对歌剧提起兴趣,得到的答案是:“要像《第五元素》里的歌剧场景那么激动人心。”

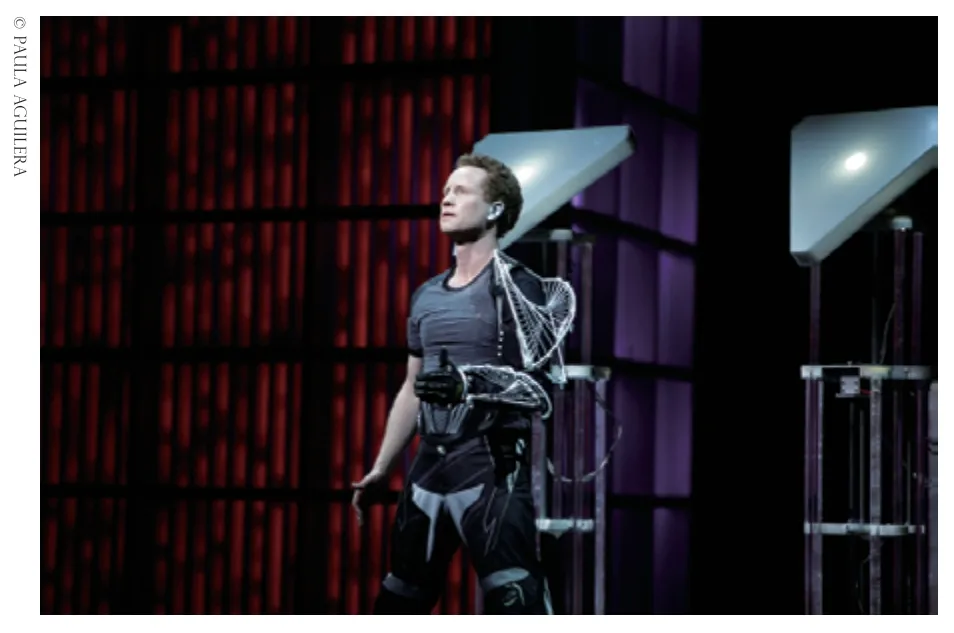

上:被誉为世界上第一部“电子游戏歌剧”的《永久死亡》剧照

***

不知为何,《剧院魅影》(The Phantom of the Opera)是唯一的特别案例。普遍来说,魔幻情节与恐怖元素在歌剧舞台上的影响力不大。吸血鬼、鬼魂,甚至科学怪人可能偶尔亮相,但都只是昙花一现。相对来说,科幻小说更具吸引力。

托德·马可福(Tod Machover)1987年创作的《瓦利斯》(Valis,根据另一本菲利普·迪克的小说改编)是我毕生首次接触到的、刻意被宣传为“科幻歌剧”(science-fiction opera)的音乐戏剧作品。马可福是麻省理工学院媒介实验室(MIT Media Lab)的音乐及媒介教授,其作品《死亡与权力》(Death and the Powers)是2012年普利策奖入围作品。《死亡与权力》以机器人为主题,因而也被贴上了“未来歌剧”(an opera for the future)的标签。

左页:歌剧《死亡与权力》剧照

但追溯起歌剧运用科幻小说作为素材的根源要深很多。正如我之前提到的,莱奥什·雅纳切克(Leoš Janáček)的《马克洛普罗斯档案》(The Makropulos Case)里的女主角,因为年轻时喝过长生不老药,是个活了整整三百年的歌剧大明星。这则故事应该介于科幻与魔幻之间。但雅纳切克更早期的歌剧《布鲁切克先生的旅行》(The Excursions of Mr. Brouček to the Moon and to the 15th Century)——正如题目所写的那样,基本上是关乎外太空与穿越时空旅行,这正是科幻小说中两个最典型的元素。

倘若你认为月球之旅是一个现代概念,那你就错了。让我郑重介绍海顿于1777年首演的歌剧《月亮上的世界》(Il mondo della luna),剧本来自18世纪威尼斯著名编剧卡洛·戈尔多尼(Carlo Goldoni)的手笔。我还得提醒你,在海顿之前,已有6位作曲家根据戈尔多尼的这个剧本谱写过音乐。

当然,直到20世纪中叶文学流派牢固确立之后,这一切才被称为“科幻小说”。有时候,这些元素只不过是附带品,或是情节转折的工具——比如说迈克尔·蒂皮特(Michael Tippett)的《新年》(New Year)或菲利普·格拉斯(Philip Glass)的《航行》(The Voyage),这两部歌剧都含有穿梭时空或翱翔星际的情节。有时候,科幻是故事的整体背景,比如说格拉斯的《第八号行星代表的产生》(Making of the Representative for Planet 8)与《第三、四、五区域间的联姻》(The Marriages Between Zones Three,Fourand Five)[这两部作品都是根据多丽丝·莱辛(Doris Lessing)的小说改编而成]。再想深一层,还有格拉斯的《沙滩上的爱因斯坦》(Einstein on the Beach),那是一个虚构故事,也有一名科学家。

有趣的是,尽管近年来电影被大量改编成歌剧,但“科幻歌剧”却仅停留在书本中。唯一的例外是霍华德·肖尔(Howard Shore)的《苍蝇》(The Fly)。作品首演一败涂地,我就不予置评了,但《苍蝇》为我的论点提供了最有力的证据。很多人都会谈及歌剧与大卫·柯南伯格(David Cronenberg)于1986年执导的同名电影的直接关系——这也有助于柯南伯格导演歌剧——但很少人留意到,歌剧剧本中的许多关键元素都是从1950年代的原著中提取出来的。

虽然在技术上算不上是改编作品,我猜我们也应该包括艾夫·范布林(Eef van Breen)的歌剧《u》(‘u’)。剧本的语言完全是克林贡语(Klingon),是《星际迷航》(Star Trek)经典电视剧与电影系列中所使用的人造语言。歌剧《u》备受观众追捧,但我不敢肯定,该作品在《星际迷航》影迷聚会上获得的空前成功,对于现实的歌剧世界有没有实质的影响。

但过了一会儿,你会察觉到一个重点。当真正的科幻小说登上歌剧舞台,比如说洛林·马泽尔(Lorin Maazel)的《1984》[改编自乔治·奥威尔(George Orwell)的作品],或保罗·鲁德(Poul Ruder)的《侍女的故事》(The Handmaid's Tale)[改编自玛格丽特·阿特伍德(Margaret Atwood)的作品]——是的,还有《苍蝇》——这些故事通常都是令人不安的、寓意灰暗的、反乌托邦的。那么,为什么歌剧进入科幻小说的次数很少,且营造出来的效果往往都很“太空歌剧”呢?

I have to admit, I was getting pretty engrossed inBlack Opera, Mary Gentle's 680-page epic of“alternative history.” An English librettist in 19thcentury Naples receives a commission from King Ferdinand for very a special opera, one that would cancel out the effects of a “black opera” about to be staged by a secret society to provoke an eruption from Mt. Vesuvius and summon the devil into the world.

上:第一部克林贡语歌剧《u》剧照

There's plenty of off-stage drama in the “white opera” as well, not least because the librettist's chief collaborator, an Italian aristocrat and dilettante composer, is now married to a soprano who once had a year-long affair with the librettist and, of course, is to star in their new production. What could go wrong?Actually, it all sounds suitably operatic until she turns out to be a zombie.

Yes, a zombie.

Once the novel shifts genres from alt-history to fantasy-horror the narrative never quite recovers.One book critic has even questioned how a novel that features “volcanoes, zombies, ghosts, love triangles,secret societies, the inquisition, cross-dressers, and a guest appearance by Napoleon Bonaparte could be so singularly devoid of tension.”

Maybe the writer should've left out Napoleon. But it did get me thinking, how often does opera really mix with zombies—or ghosts, ghouls and vampires,for that matter? Anne Rice, the writer who infamously injected the horror genre with new blood in her 1976 novelInterview with a Vampire, shifted gears a few years later withCry to Heaven, an “opera” novel that recreated the world of 18th-century castrati with nary a vampire in sight.

Nor, strangely enough, will you find many sopranos in the subgenre of science fiction known as “space opera.” Much as westerns were once derided as“horse operas,” and episodic afternoon television sponsored by detergent companies was labeled “soap opera,” these melodramatic tales of war, romance and interplanetary travel are rarely taken seriously by serious devotes.Flash Gordon?Star Wars? The genre snob is already sneering, “Those are just space operas…”

To get to real sopranos you have to go hardcore—and then almost entirely on the bookshelves. Anne McCaffrey, whose literary oeuvre did for dragons what Rice did for vampires, also wrote herCrystal Singertrilogy about a failed opera singer who finds herself recruited to another planet to mine crystals, using her perfect pitch to operate high-risk machinery. Philip K. Dick's post-apocalyptic taleDo Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?follows a San Francisco bounty hunter who makes a living by tracking down androids posing as humans. He finds himself at the opera house and figures out that a soprano is an android. How?He's heard a recording of the same music by Christa Ludwig, and the android doesn't sing with enough emotion. (By the time Dick's 1968 novel became the 1982 filmBlade Runner, the story shifted to Los Angeles and the opera singer became a stripper, which pretty much says it all.)

Getting back to vampires, though, perhaps the most satisfying example of opera in speculative fiction comes from Somtow Sucharitkul. Before he founded the Bangkok Opera, the composer-conductor also wrote in various prose genres under the name S.P.Somtow. His novelVampire Junctionintroduces a 12-year-old rock star who turns out to be a 2000-yearold vampire. His nemesis is an aging conductor who instantly recognizes the voice as the same boy soprano he auditioned decades earlier.

Though Somtow wroteVampire Junctionlong before Rice'sInterview, his novel wasn't published until the mid-1980s. It eventually made the Horror Writers Association's list of “40 Best Horror Novels,”but publishers had long thought it far too weird—and probably too violent—to foist on an unsuspecting public (the writing style matches the visuals of horror films with the pacing of music videos in a subgenre dubbed “splatterpunk”). Really, though, I think it was all the opera references.

A few years ago, after his production ofDas Rheingoldin Bangkok, I asked Somtow whether he really thought the horror-reading public would understand his allusions toThe Magic FluteandBluebeard's Castle, or see that the final destruction of the vampires' lair was a fiery tribute toGötterdämmerung. “No,” he admitted mischievously. “But the two or three percent who do will think it's really cool.”

Before we dismiss the movies completely, though,let's give due credit to Luc Besson's filmThe Fifth Element, which despite fitting most people's definition of “space opera” does actually feature an opera singer. Seeing a black-tied Bruce Willis listening to a blue-skinned diva launch from a melancholy moment inLucia di Lammermoorinto a literally inhuman barrage of vocal technique was the film's most memorable moment.

Just as I was thinking that performance was probably still echoing somewhere in the world,I heard aboutPermaDeath. Billed as the world's first “videogame opera,” its premiere in Boston last September had audiences participating through a phone app. With music by Dan Visconti, the story was written by Cerise Lim Jacobs and inspired by her son,Pirate Epstein. When Jacobs had asked her son what would make him excited about opera, he answered immediately: “If it could be as thrilling as the opera scene inThe Fifth Element.”

***

歌剧《永久死亡》剧照

For some reason,The Phantom of the Operanotwithstanding, elements of fantasy and horror have not made a big impact on the opera stage. Vampires,ghosts and even Frankenstein's monster may have made brief appearances, but they quickly vanish without a trace. Science fiction, though has had a bit more traction.

Tod Machover's 1987 stage workValis(based on another Philip K. Dick story) was the first music-theatre piece I encountered specifically billed as “sciencefiction opera.” Machover, who by day is a professor of music and media at the MIT Media Lab, was later a finalist for the 2012 Pulitzer Prize withDeath and the Powers, which featured robots and was labeled “an opera for the future.”

But the roots of science fiction as operatic material go much deeper. Leoš Janáček'sMakropulos Case, as I've mentioned before, concerns a 300-year-old opera diva who drinks an elixir of immortality in her youth,which falls somewhere between science fiction and fantasy. But Janáček's earlier operaThe Excursions of Mr. Brouček to the Moon and to the 15th Century—true to its title—is essentially about outer space and time travel, two classic elements of science fiction.

Lest we think living on the moon is a strictly modern idea, let me introduce you to Haydn's 1777 operaIl mondo della luna, with a text by the 18thcentury Venetian playwright Carlo Goldoni. And keep in mind that six other composers had already set Goldoni's libretto to music before Haydn got around to it.

None of this was called “science fiction,” of course,till the mid-20thcentury once the literary genre had become firmly established. Sometimes those elements are simply incidental—or mere plot devices—such as the time travel and interplanetary notions of Michael Tippett'sNew Yearor Philip Glass's operaThe Voyage.Sometimes they provide essentially the entire setting,as with Glass'sMaking of the Representative for Planet 8andThe Marriages Between Zones Three, Four and Five(both based on books by Doris Lessing). Come to think of it, there was also Glass'sEinstein on the Beach, which at least was fiction and had a scientist.

Funnily enough, despite the plethora of films being turned into operas these days, “science-fiction opera” tends to keep to the books. There was, of course, Howard Shore'sThe Fly. Generally, the less said about that opera the better, but it does prove the point. Much was made about its connection to David Cronenberg's 1986 film—it helped that Cronenberg also directed the opera—but few people realized that many key elements in libretto were taken from the original 1950s story.

And though it's technically not an adaptation,I suppose we should include Eef van Breen's‘u',an opera composed entirely in Klingon (a fictional language from the TV and movie seriesStar Trek).‘U'has been a huge hit with audiences, though I'm not sure that performances atStar Trekconventions are an accurate barometer of the opera world.

But after a while, you start to notice something.When true science fiction makes it to the opera stage,such as Lorin Maazel's1984(after George Orwell) or Poul Ruder'sThe Handmaid's Tale(after Margaret Atwood)—or, yes, evenThe Fly—the stories are usually dark, disturbing, dystopian. Why is it, then, that the few times that opera has made its way into science fiction, the results are usually, well, space opera?

歌剧《永久死亡》剧照