Differentiating Crohn’s disease from intestinal tuberculosis

2019-02-21SaurabhKediaPrasenjitDasKumbleSeetharamaMadhusudhanSiddharthaDattaguptaRajuSharmaPeushSahniGovindMakhariaVineetAhuja

Saurabh Kedia, Prasenjit Das, Kumble Seetharama Madhusudhan, Siddhartha Dattagupta, Raju Sharma,Peush Sahni, Govind Makharia, Vineet Ahuja

Abstract Differentiating Crohn’s disease (CD) and intestinal tuberculosis (ITB) has remained a dilemma for most of the clinicians in the developing world, which are endemic for ITB, and where the disease burden of inflammatory bowel disease is on the rise. Although, there are certain clinical (diarrhea/hematochezia/perianal disease common in CD; fever/night sweats common in ITB), endoscopic(longitudinal/aphthous ulcers common in CD; transverse ulcers/patulous ileocaecal valve common in ITB), histologic (caseating/confluent/large granuloma common in ITB; microgranuloma common in CD), microbiologic(positive stain/culture for acid fast-bacillus in ITB), radiologic (long segment involvement/comb sign/skip lesions common in CD; necrotic lymph node/contiguous ileocaecal involvement common in ITB), and serologic differences between CD and ITB, the only exclusive features are caseation necrosis on biopsy, positive smear for acid-fast bacillus (AFB) and/or AFB culture, and necrotic lymph node on cross-sectional imaging in ITB. However,these exclusive features are limited by poor sensitivity, and this has led to the development of multiple multi-parametric predictive models. These models are also limited by complex formulae, small sample size and lack of validation across other populations. Several new parameters have come up including the latest Bayesian meta-analysis, enumeration of peripheral blood T-regulatory cells, and updated computed tomography based predictive score. However, therapeutic anti-tubercular therapy (ATT) trial, and subsequent clinical and endoscopic response to ATT is still required in a significant proportion of patients to establish the diagnosis. Therapeutic ATT trial is associated with a delay in the diagnosis of CD, and there is a need for better modalities for improved differentiation and reduction in the need for ATT trial.

Key words: Crohn's disease; Intestinal tuberculosis; Endoscopy; Computed tomographic enterography; Granuloma

INTRODUCTION

South Asian and South East Asian countries are at the crossroads of epidemiologic transition[1,2]with the decline in the incidence of infectious diseases and an increase in chronic non-infectious diseases, and one such transition is exemplified by the chronic granulomatous disorders of the intestine: intestinal tuberculosis (ITB), an infectious disease and Crohn’s disease (CD), a sub-type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).Both have different etiologies, but similar presentations and are difficult to differentiate[3]. This problem is compounded by the rise of IBD in TB endemic areas[4,5]and the rise of ITB in developed countries because of the HIV pandemic[6]. IBD burden is on the rise in TB endemic regions and as per a recent report, the overall disease burden of IBD in India is the second highest in the World after USA[5], and hence there is a constant challenge for the gastroenterologists practicing in these regions to decipher the CD/ITB dilemma in an index patient.

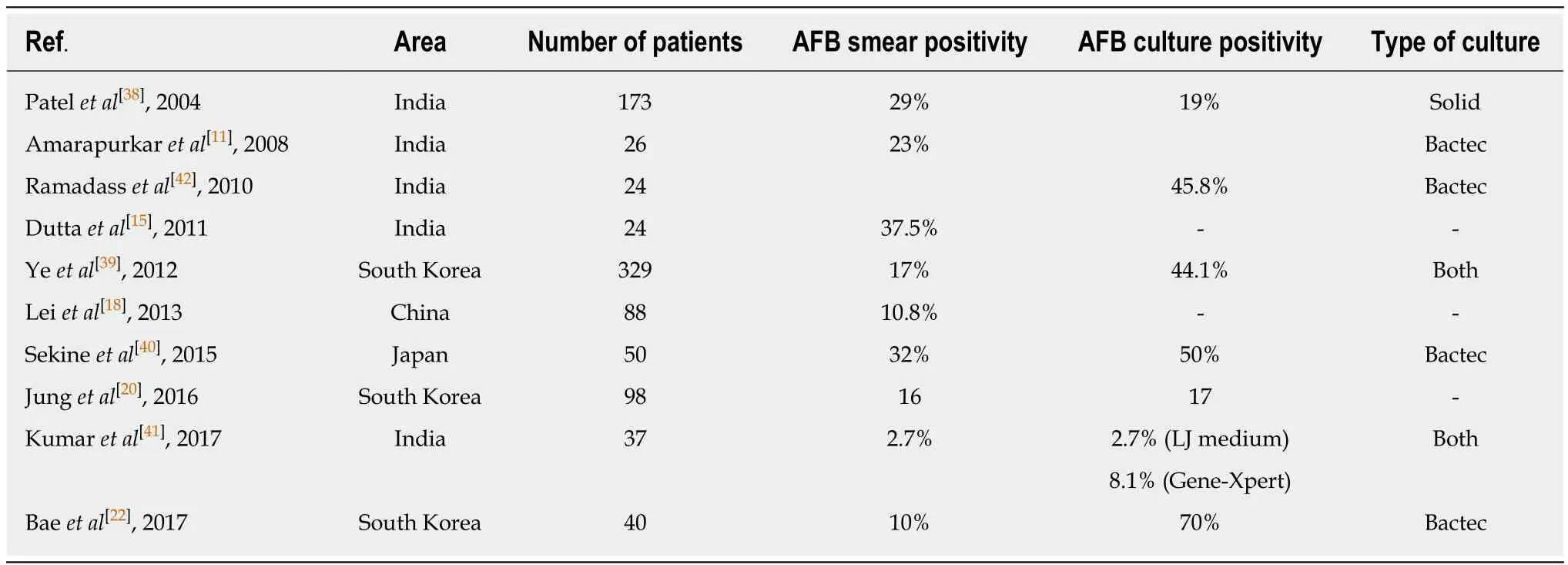

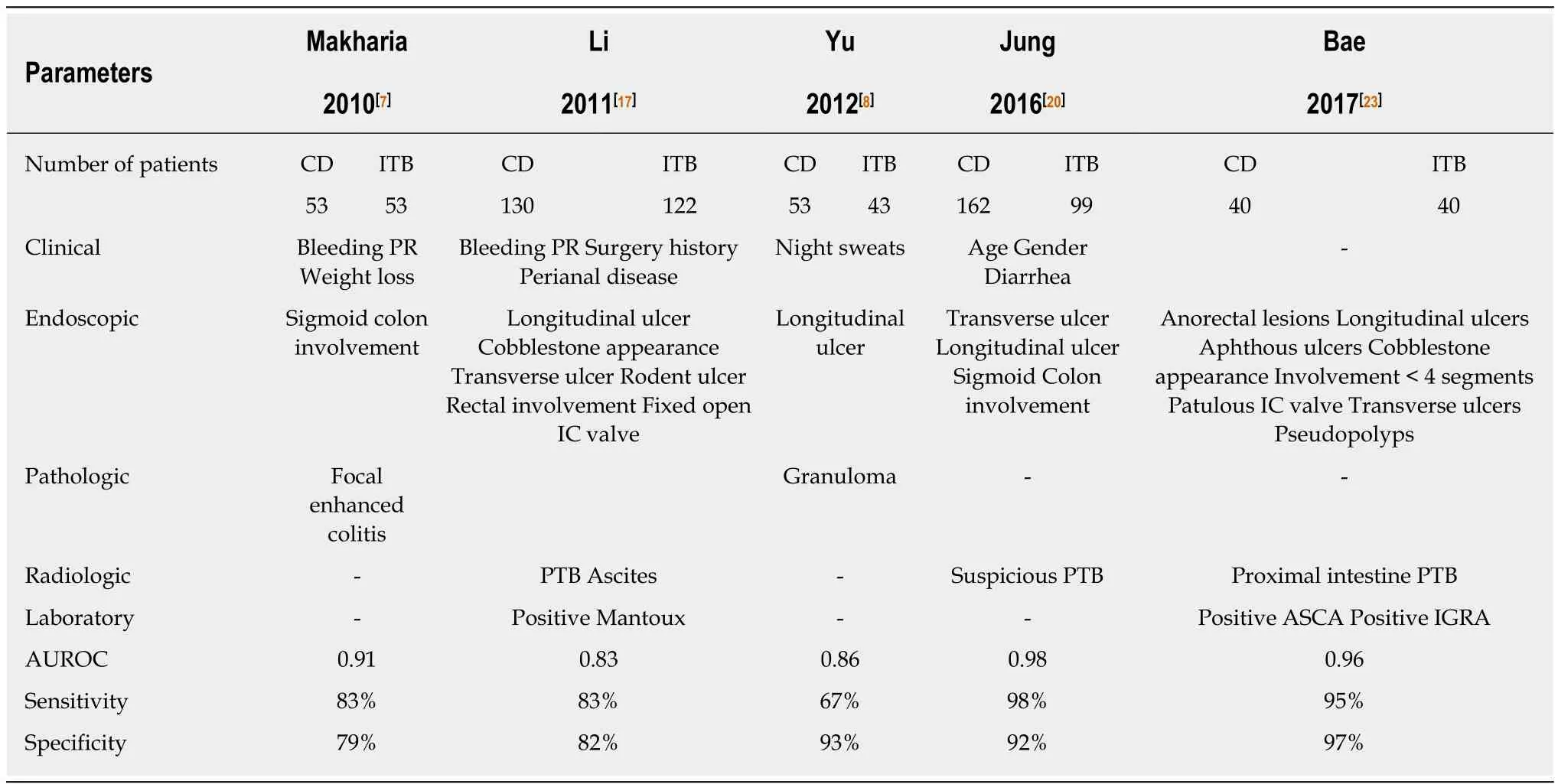

The problem chiefly arises because of poor sensitivity of tests used as a gold standard for diagnosis of ITB (Table 1). There have been multiple reports on the clinical, endoscopic, pathologic, microbiologic, serologic and radiologic features in differentiating CD and ITB, and several predictive models have been developed[7-12].This review summarizes the available evidence on differentiating CD and ITB,beginning with the individual features, followed by models incorporating a combination of features, and ending with perspective on future directions.

CLINICAL FEATURES

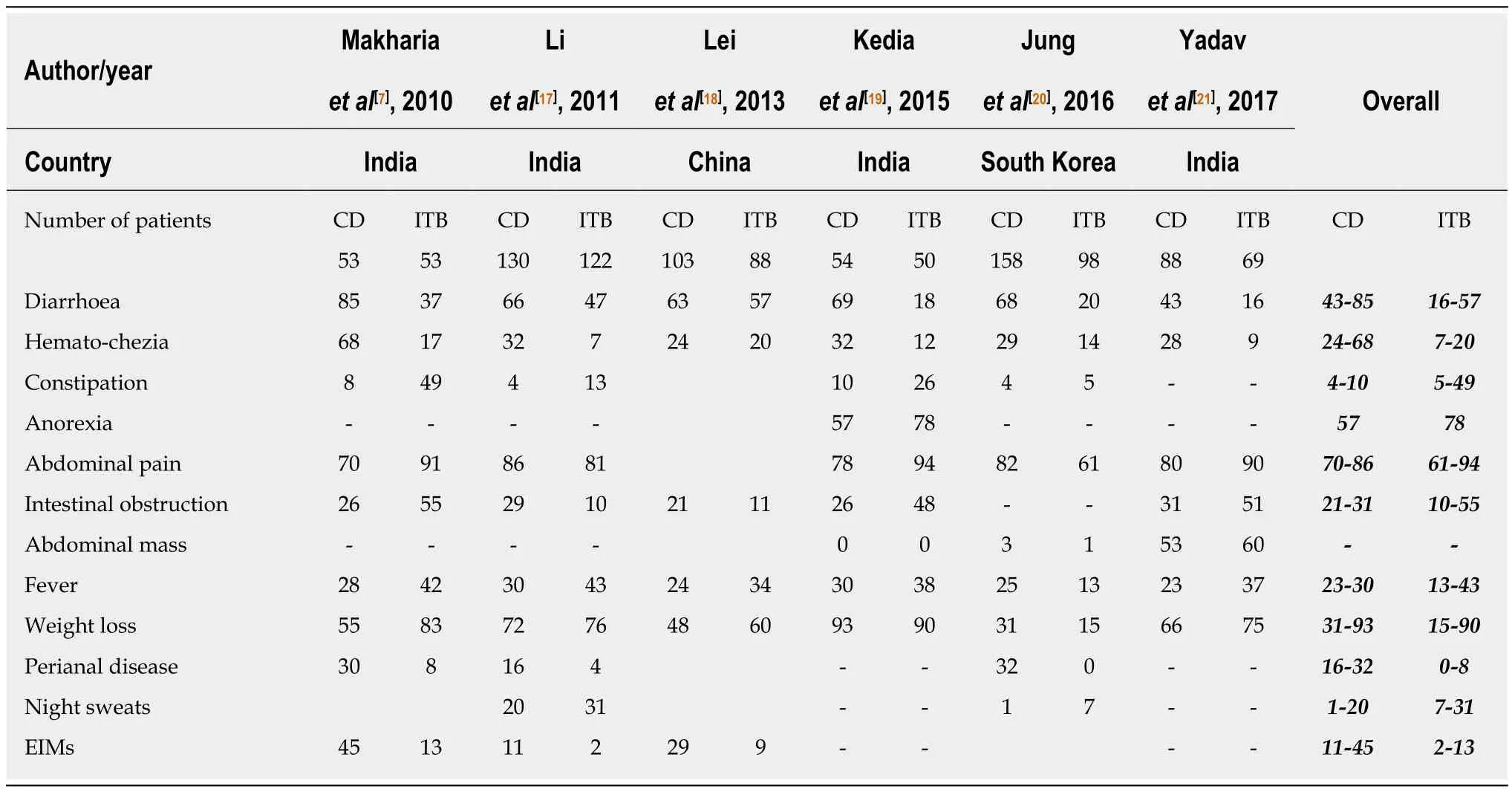

The clinical features of both disorders include abdominal pain, recurrent partial intestinal obstruction, fever, anorexia, weight loss, chronic diarrhea, hematochezia,perianal disease, and extra-intestinal manifestations (EIMs) including arthralgia,aphthous ulcers, dermatologic and ocular manifestations[13-16]. There is significant heterogeneity among the available studies regarding the differentiating clinical manifestations. However, most of the studies report diarrhea, hematochezia, perianal disease, and EIMs as being more common in CD than ITB (Table 2)[7,17-21]. Except for a few studies, the duration of the disease has been longer in patients with CD, and longer disease duration favors a diagnosis of CD over ITB. A recent meta-analysisincluded all studies from inception till September 2015 and compared all the clinical,endoscopic, pathologic, radiologic, and serologic features between the two groups[12].Among the clinical features, diarrhea, hematochezia, perianal disease, and EIMs favored the diagnosis of CD, while fever, night sweats, lung involvement and ascites favored the diagnosis of ITB. However, none of these features is exclusive for either disease and alone cannot diagnose CD or ITB. Unlike CD, tuberculosis can have varied manifestations involving extra-intestinal organs, and may even present as inflammatory pseudotumors[22].

Table 1 Rates of smear and culture positivity for Mycobacterium tuberculosis in patients with intestinal tuberculosis

ENDOSCOPIC FEATURES

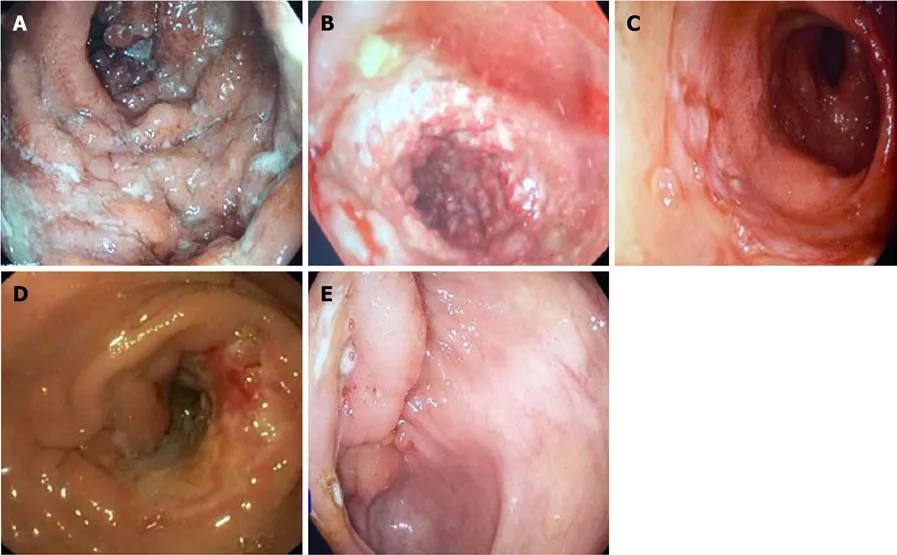

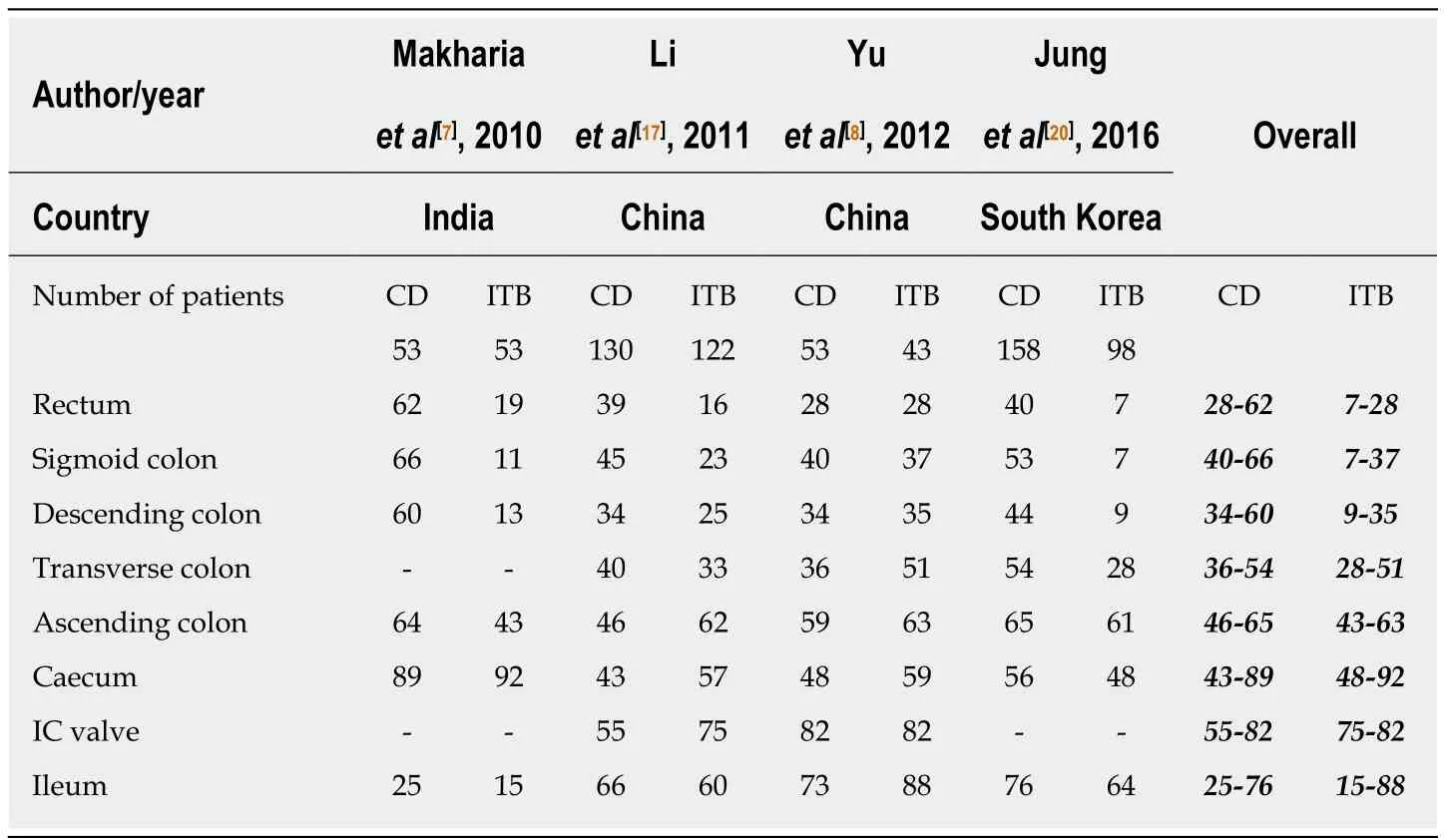

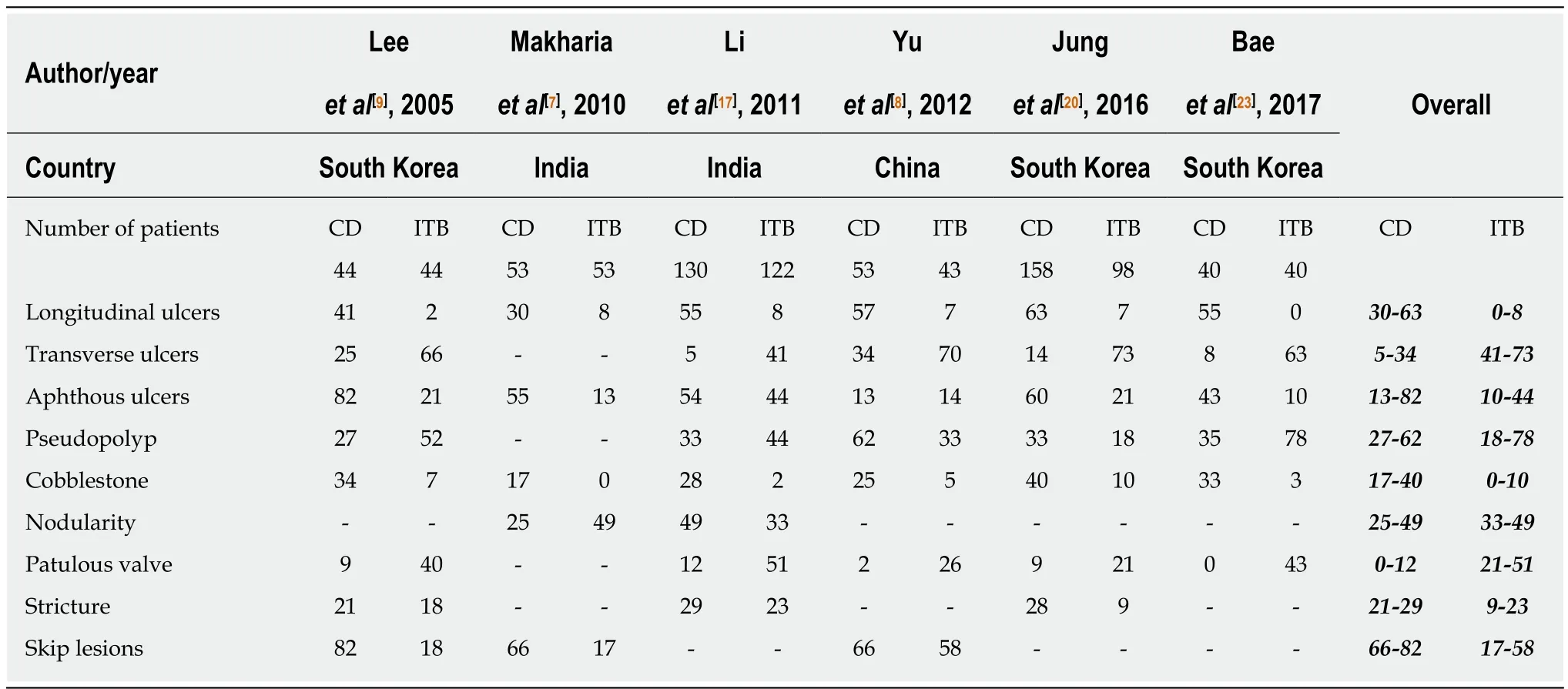

Among the endoscopic features, left colonic involvement and presence of longitudinal ulcers, aphthous ulcers, cobblestoning, and skip lesions are more common in CD(Figure 1), whereas presence of transverse ulcers and patulous ileocaecal valve are more common in ITB (Tables 3 and 4)[7-9,17,20,23]. Other features including pseudopolyps,strictures, and nodularity have not been reported in all the studies, and there is heterogeneity among the studies with respect to their frequencies between CD and ITB. A predictive model based upon endoscopic features was reported by Lee et al in 2006[9], where they included eight features: transverse ulcers, fewer than 4 segment involvement, patulous IC valve, and pseudopolyps (common in ITB), and longitudinal ulcers, aphthous ulcers, cobblestoning, and anorectal lesions (common in CD). A score of +1 and -1 was assigned for the presence of each feature common to CD and ITB respectively, and composite score > 0 was suggestive of CD, < 0 was suggestive of ITB, and this model could make a correct diagnosis in 87.5% patients with a positive predictive value (PPV) of 95% for CD, and 89% for ITB. As per the latest meta-analysis[12], the presence of recto-sigmoid involvement, longitudinal ulcers,aphthous ulcers, cobblestone appearance, luminal stricture, mucosal bridge, and skip lesions favored CD, whereas the presence of IC valve and cecal involvement,transverse ulcers and patulous IC valve favored ITB. Like the clinical features,endoscopic features are also not exclusive and alone cannot diagnose either disease.

PATHOLOGIC FEATURES

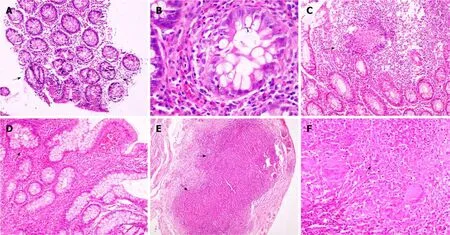

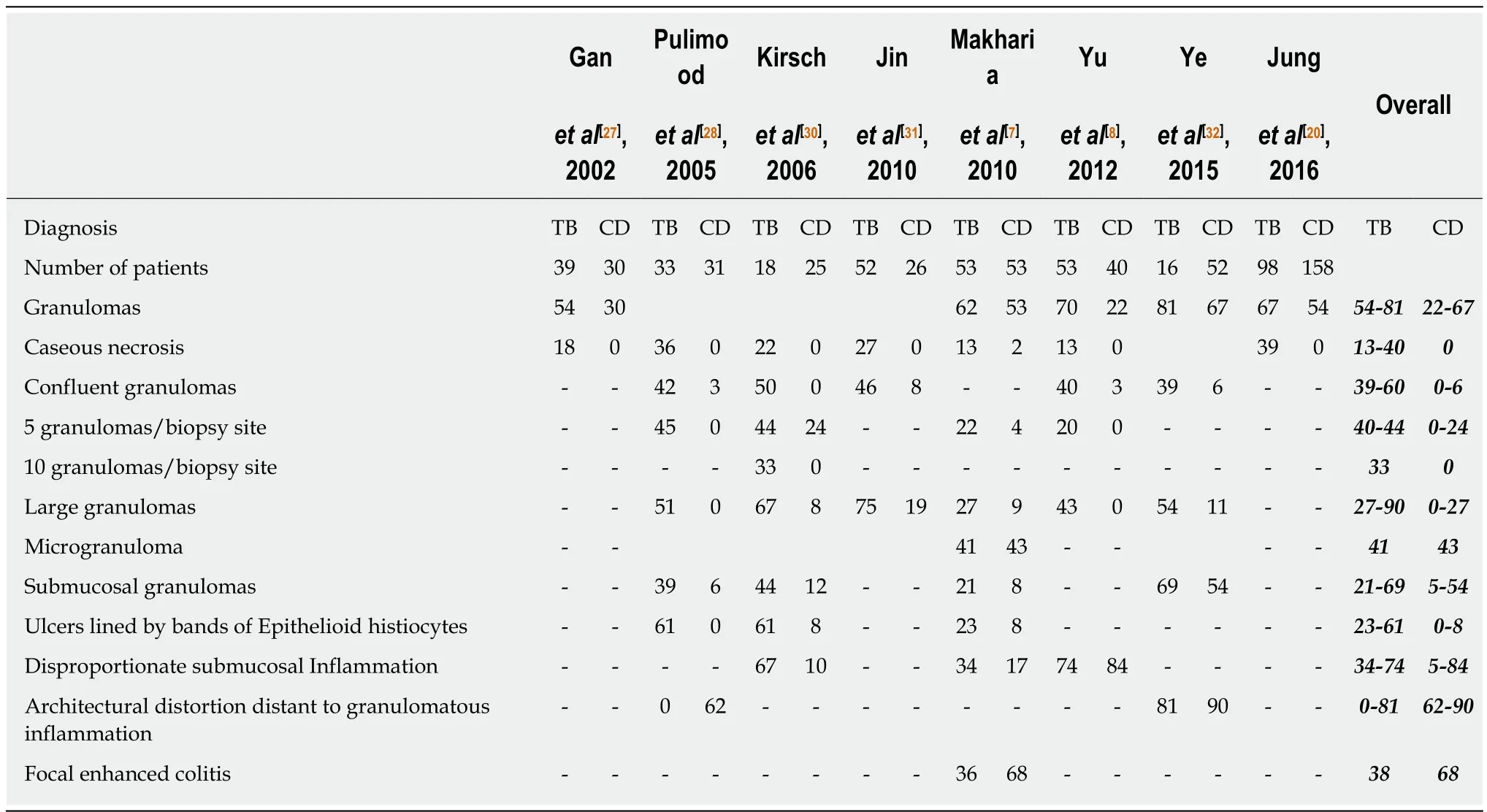

Both the disorders are characterized by chronic granulomatous inflammation in the GI tract, and pathological features can be classified into architectural and inflammatory. Architectural abnormalities such as crypt distortion (non-parallel crypts, variable diameter or cystically dilated crypts), crypt branching (> 2 branched crypts), crypt shortening, decreased crypt density and irregular mucosal surface,though more common in CD are also seen in ITB[24,25]. Inflammatory features include focal/patchy inflammation, basal plasmacytosis, increased intra-epithelial lymphocytes, transmucosal inflammation, focal cryptitis, aphthoid ulcers,disproportionate submucosal inflammation, nerve fiber hyperplasia, proximal location of ulceration and architectural distortion, metaplasia (pseudopyloric in ileum and paneth cell in the colon), and granulomas (Table 5). There may be widening of thesubmucosa (more in CD) with some degree of edema in the vicinity of ulcer beds with dilated lymphatics[26]. Surgical specimens may reveal the presence of transmural cracks and fissures, which are rare in ITB, and if present they usually do not extend beyond the submucosa, whereas in CD they are more common and may extend till serosa[24,26]. Granuloma, a collection of epithelioid histiocytes (macrophages) with vaguely defined outlines, is seen more commonly in ITB and is the most important feature for differentiating ITB from CD. Tubercular granulomas are usually large (>200 m), confluent, dense (> 5-10/hpf), located in submucosa, and are characterized by central caseation, which is diagnostic and exclusive for ITB[7,8,20,27-32]. Granulomas in CD are usually small (microgranuloma), discrete, ill-defined and sparse (Figure 2).Granulomas in the surrounding lymph nodes can be seen in both diseases[33-35], but lymph nodal granulomas in the absence of intestinal inflammation are seen only in ITB. Other features which are more common in ITB include submucosal granulomas,ulcers lined by a band of epithelioid histiocytes, and disproportionate submucosal inflammation whereas features more common in CD include architectural distortion distant to granulomatous inflammation, and focal enhanced colitis. In a recent metaanalysis of 10 studies including 692 patients (316 ITB, 376 CD) caseating necrosis,confluent granulomas, and ulcers lined by epithelioid histiocytes were the most accurate features in differentiating ITB from CD, with a pooled sensitivity, specificity,and area under curve (AUC) of 21%, 100%, 0.99; 38%, 99%, 0.94; and 41%, 95% and 0.90 respectively[36]. In the latest meta-analysis by Limsrivillai et al, features more common in ITB included confluent granuloma, large granuloma, multiple granulomas per section, submucosal granuloma, and granuloma with surrounding cuffing lymphocytes[12].

Table 2 Comparison of clinical features between Crohn’s disease and intestinal tuberculosis

One recent study from India reported that immune-histochemistry (IHC) for CD-73 in biopsies could differentiate granulomas of CD and TB with high diagnostic specificity[37]. However, this has not been replicated in other studies and a recent analysis from our center (unpublished). In another study, characterization of collagen fibers in intestinal biopsies using Masson’s Trichrome staining and second harmonic generation imaging (SHG) and two-photon excited fluorescence (TPEF) imaging showed that content of collagen fiber and fiber deposits was significantly higher in ITB than CD, and could differentiate the two disorders[38].

MICROBIOLOGIC TESTS

Figure 1 Endoscopic images. A: Longitudinal ulcer in a patient with Crohn’s disease; B: Coblestoning in a patient with Crohn’s disease; C: Deep ileal ulcer in apatient with Crohn’s disease; D: Transverse ulcer with a stricture in a patient with intestinal tuberculosis; E: Ulcerated bulky ileocaecal valve in a patient with intestinal tuberculosis.

Like any other infectious disease demonstration of Mycobacterium bacilli would be diagnostic of tuberculosis, but since intestinal TB is a paucibacillary disease,demonstrating the organism is difficult, and this accounts for poor sensitivity of these tests. Demonstrating the bacillus with acid-fast bacillus (AFB) staining would be easiest, but is associated with a very poor sensitivity of 2.7%-37.5% (Table 1)[15,18,20,23,39-42]. There are several methods of culturing the bacillus including the solid phase medium (LJ medium), which was used earlier, but took a very long time, and has been replaced by BACTEC (mycobacterium growth indicator tube). The method is based on the detection of carbon dioxide (CO2) released by actively proliferating Mycobacteria. The elevated CO2 concentration lowers the pH in the medium, which in turn produces a color change in a sensor in the vial, which is detected by a reflectometric unit in the instrument. The sensitivity of AFB culture varies from 19%-70% (Table 1)[20,23,39-43]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for AFB in endoscopic biopsies is not exclusive for ITB, and as a stand-alone test cannot be diagnostic for ITB[10,27,31,44-46].In a recent meta-analysis of 9 studies, the pooled sensitivity and specificity of PCRAFB was 44% and 95% respectively[47]. The role of Gene-Xpert MTB/RIF assay in intestinal biopsies has been less well studied, and in a study of 37 patients with ITB,the sensitivity and specificity of gene Xpert was 8.1% and 100% respectively[42].Therefore, among the microbiologic tests, AFB stain, AFB culture, and gene-Xpert MTB are diagnostic for ITB, however, these tests are associated with very poor diagnostic sensitivity, limiting their role in the differential diagnosis of CD vs ITB.

RADIOLOGY

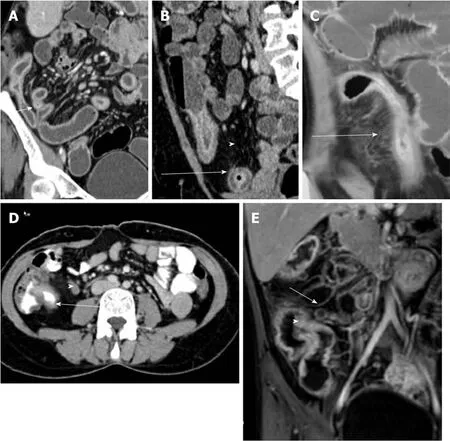

Computed tomographic (CT)/magnetic resonance (MR) enterography are the preferred imaging modalities for evaluating and differentiating between patients with CD and ITB[48,49]. As compared to endoscopy, cross-sectional imaging has the advantage of non-invasively imaging the entire intestinal tract and it complements other investigations in differentiation between CD and ITB[50]. It also overcomes the limitations of endoscopic examination: poor access to segments of the small intestine other than distal ileum or proximal jejunum, and inability to evaluate the intestine distal/proximal to the strictures. In recent study from India, CT findings that were more common in patients with CD as compared to ITB were involvement of the left colonic segment (22% vs 6%), long-segment involvement (69% vs 28%), presence of skip lesions (63% vs 42%), and presence of comb sign (44% vs 20%) (Figure 3). On the other hand, the involvement of ileocecal area (70% vs 43%), shorter length of involvement, and presence of lymph nodes larger than 1 cm (20% vs 2%) were more common in ITB[19]. In the same study, a predictive model based on three characteristics(ileocecal area involvement, larger lymph nodes, and long-segment involvement) had good specificity (90%) and positive predictive value (80%) in differentiating CD from ITB. Based upon these three features, a risk score was calculated: [long-segment involvement + (1 - ileocaecal region involvement) + (1 - lymph nodes ≥ 1 cm)], where presence of long-segment involvement = 1, ileocaecal region involvement = 1 and lymph nodes ≥ 1 cm = 1). The risk score ranged from 0-3, and the scores 0 and 1 had good specificity and PPV for ITB whereas the score 2 and 3 had good specificity and PPV for CD. In a study from China, asymmetric wall thickening, segmental intestinal involvement, comb sign, and mesenteric fibro-fatty proliferation were significantly more common in patients with CD than in those with ITB[51]. Segmental small intestinal involvement and comb sign were independent predictors of CD, and adding these features to colonoscopic findings significantly improved the accuracy of the diagnosis[52]. Further, a recent meta-analysis of 6 studies on CT[19,51-55], including 612 patients (417 CD, 192 ITB) reported that lymph nodes with necrosis had the highest diagnostic accuracy and was exclusive for ITB[56]. Among other features, comb sign and skip lesions had the best diagnostic accuracy in differentiating CD from ITB with a sensitivity, specificity, and AUC of 82%, 81%, 0.89; and 86%, 74%, 0.87 respectively.Left colonic involvement, asymmetric thickening, and fibrofatty proliferation had a poor sensitivity of approximately 40%, but good specificity approaching 90%. Mural stratification had a poor diagnostic accuracy, and this could relate to transmural involvement in both CD and ITB. Long segment and ileocaecal area involvement also had poor accuracy, as they were reported with variable definitions, and only in 2 or 3 studies. In the meta-analysis by Limsrivilai et al, comb sign and fibrofatty proliferation significantly favored the diagnosis of CD whereas short segment involvement favored the diagnosis of ITB[12].

Table 3 Comparison of different sites of involvement on colonoscopy between patients with Crohn’s disease and intestinal tuberculosis

Visceral fat is a component of mesenteric fat and mesenteric fatty proliferation is one of the hallmarks of CD, being recognized as early as 1932 when Burril B. Crohn described it in his first mention about Crohn’s disease[57]. Fat hypertrophy, fat wrapping, and creeping fat have been associated with active CD[58], and visceral fat has been correlated with disease outcomes in patients with CD[59]. Two studies have shown that visceral fat is higher in patients with CD[21,60]and a recent study from our center showed that visceral to subcutaneous fat ratio (VF/SC) was significantly higher in CD than ITB, and VF/SC ratio of 0.63 had a sensitivity, specificity, and AUC of 81%, 82% and 0.9 respectively to differentiate CD and ITB[21]. This was validated in a separate validation cohort, with similar diagnostic accuracy. We further combined the CT features and VF/SC ratio to develop an updated model and showed that necrotic lymph nodes, long segment involvement, and VF/SC ratio > 0.63 were most significantly different between CD and ITB, both in the development and validation cohort[61]. Like the previous meta-analysis, presence of necrotic lymph node was exclusive for ITB, and so was not included in the model. The risk score was defined as: VF/SC ratio > 0.63 + long segment involvement (≥ 3 cm); where VF/SC ratio >0.63 = 1 and presence of long segment involvement = 1. A risk score of 2 had anexcellent specificity of 100% and 97%, and a sensitivity of 52% and 50% for the diagnosis of CD in the development and validation cohorts respectively. Therefore,according to this study, presence of necrotic lymph node was exclusive for ITB,whereas long segment involvement and VF/SC ratio > 0.63 was almost exclusive for CD. However, this finding needs validation from other centers in a larger population.

Table 4 Comparison of colonoscopic findings between patients with Crohn’s disease and intestinal tuberculosis

Multiple series have shown that evidence of concomitant pulmonary TB in a patient with CD/ITB dilemma favours a diagnosis of ITB and chest-X ray has revealed evidence of active/healed pulmonary TB in 3%-25% patients with ITB. In a prospective study, we recruited consecutive treatment naïve patients with suspected ITB (no evidence of definite diagnosis at presentation) who underwent CECT chest at presentation. Interestingly, we found that of 55 such patients, 13 (24%) had evidence of active TB on CT chest, and all these patients showed clinical, endoscopic and radiologic response to ATT, and were finally confirmed to have ITB (unpublished).Therefore, addition of CT chest increased the sensitivity of ITB diagnosis from 25% to 51%. Therefore, we recommend both CT chest and CT enterography in the diagnostic evaluation of a patient with ulcero-constrictive intestinal disease, as evidence of active TB on CT chest will clearly tilt the diagnosis towards ITB.

SEROLOGIC AND IMMUNOLOGIC TESTS

Mantoux and interferon gamma release assays (IGRA) are markers for latent tuberculosis, and a positive test although would suggest a diagnosis of ITB, as a standalone test, these are not confirmatory for ITB[62]. Positive Mantoux has been reported in 50%-100% patients with ITB, however, neither a positive Mantoux confirms a diagnosis of ITB, nor a negative Mantoux refutes a diagnosis of ITB[63,64].There have been several meta-analyses on the role of IGRA, and they report a pooled sensitivity and specificity of approximately 80% in differentiating ITB from CD[65,66].Both IGRA and Mantoux are predictive of latent TB rather than active TB and hence a positive or a negative IGRA will neither rule in or rule out the diagnosis of ITB.

Positive serology for anti-saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody (ASCA) has no role in differentiating CD from ITB, as shown in two studies from India[67-69]and in recent meta-analyses, where ASCA was not found useful and in 1 of the meta-analysis, the diagnostic accuracy of ASCA was only 57%[66].

T-regulatory cells (CD4+CD25+FOXP3+) are regulators of inflammation and their peripheral blood frequency has been showed to be low in patients with CD and high in patients with pulmonary TB. In a preliminary study, it was shown that FOXP3 mRNA expression was significantly upregulated in the colonic mucosa of patients with ITB as compared to CD[70]. We further, showed that the frequency of FOXP3+ T-regulatory cells in peripheral blood was significantly higher in ITB as compared to CD, and based upon ROC curve analysis, a cut-off of 32.5% had an excellent diagnostic accuracy (AUC:0.91) with a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 90% in differentiating CD and ITB[71]. These findings were further validated in a cohort of 73 patients, and a similar cut-off had a sensitivity, specificity, and PPV of 81%, 83%, and 91% respectively (unpublished). Therefore, quantification of FOXP3 cells in peripheral blood may be an upcoming diagnostic marker, but requires further validation from other centers.

Figure 2 Colonic biopsy. A: Patchy distortion of crypt architecture (arrows) (× 40). B: Features of focal active cryptitis are noted (arrow) (× 200). C: Colonic biopsy in a case of Crohn’s disease shows pericrypt mucosal microgranuloma (arrow) (× 40). D: Ileal biopsy in a case of ileocaecal tuberculosis shows blunting of ileal villi with crypt branching (arrow) (× 100). E: Serosal confluent necrotizing epithelioid cell granulomas (arrows) were noted (× 40). F: Photomicrograph showing an epithelioid cell granuloma with central necrosis (arrow) and Langhan’s giant cells (× 200).

PREDICTIVE MODELS

Except for positive AFB smear, culture, gene-Xpert, and caseating granulomas on biopsy and necrotic lymph nodes on imaging, none of the other discussed features are diagnostic in a patient with CD/ITB dilemma. Moreover, most of these exclusive features are also present in less than 50% of patients, thereby limiting the diagnostic accuracy of a single feature/modality in differentiating CD and ITB. Therefore, there have been several reports on multi-parametric models, that have incorporated more than 1 feature across single or multiple diagnostic modalities, in differentiating CD and ITB (Table 6). In a study from India, hematochezia, weight loss, sigmoid colon involvement, and focal enhanced colitis were independent predictors for diagnosis of CD/ITB, and a score based on these variables had an AUC of 0.91 in differentiating CD and ITB[7]. In another study from China, a model based on clinical features included hematochezia, surgery history, perianal disease, concomitant pulmonary tuberculosis, ascites, and positive Mantoux, and an endoscopic model included rectal involvement, longitudinal ulcer, cobble-stoning, fixed open IC valve, ring ulcer, and rodent ulcer. Both these models had moderate sensitivity and specificity of approximately 80% in differentiating CD and ITB[17]. Another Chinese study included night sweats, longitudinal ulcers, and granulomas as variables for the predictive model and this model had good diagnostic accuracy with an AUC of 0.86[8]. In a Korean study of 261 patients, the variables selected for the predictive model were age,gender, diarrhea, transverse ulcer, longitudinal ulcer, sigmoid colon involvement, and suspicion of pulmonary TB. The AUC for differentiating CD and ITB was 0.98, and on validation in a separate cohort, the accuracy was similar with an AUC of 0.92[20].Another Korean study integrated the colonoscopic model (developed earlier by the same group) with laboratory (ASCA and IGRA) and radiologic parameters (proximal small intestinal involvement and pulmonary TB on chest-X ray) and found an accuracy of 96% in differentiating CD and ITB[23].

However, these predictive models are limited by a small sample size, lack of validity in other populations, and inclusion of features which may not be applicableto other populations (age/gender). Most of these models have not evaluated all the features (most are lacking in radiology), and have complex formulae which are difficult to apply in the clinics.

Table 5 Comparison of pathologic findings between Crohn’s disease and intestinal tuberculosis

The latest review by Limsrivilai et al[12]included meta-analysis of 55 features: age,gender, 14 clinical manifestations, 3 inflammatory markers, 18 colonoscopic findings,11 pathologic findings, 5 CT findings, and 2 serological findings (ASCA and ANCA).Among these features, the predictor variables with significant odds ratio and low heterogeneity were selected to build the model (included clinical, endoscopic and pathologic parameters). The model used the local prevalence of ITB vs CD for pre-test probability and estimates the probability of ITB and CD which is calibrated to local prevalence. This model considers the effect of each variable independent of whether the results are positive or negative, and can be applied at any center by using only the available parameters. However, the applicability of this model depends upon the local prevalence of CD and ITB, and in the absence of such data, this model cannot be applied. Secondly, the model depends on pathology, which requires a dedicated gastrointestinal pathologist, which would not be available at peripheral centers. The model does not include radiology, which has an important role in differentiating CD and ITB, and the model needs to be validated in other populations.

THERAPEUTIC ATT TRIAL

With limited diagnostic accuracies of various modalities and the mentioned limitations of predictive models, often, differentiating CD and ITB is not possible and one needs to start therapy. Treating with steroids in such a situation would be disastrous if the patient has underlying ITB, and therefore, this dilemma is circumvented with a therapeutic anti-tubercular therapy (ATT) trial. Recent Asia-Pacific consensus statements for CD have also mentioned, that in a patient with CD/ITB dilemma, the diagnosis of CD should only be considered in a patient who doesn't respond to ATT, and subsequently responds to CD-specific therapy[72]. In a recent report from S. Korea, 48% of patients with ITB required a therapeutic ATT trial for final diagnosis, and 18% of patients with CD received ATT initially, although the temporal trend in misdiagnosing CD as ITB showed a declining trend, whereas,reverse trend was observed in misdiagnosing ITB as CD[73].

Figure 3 Coronal computed tomography images in patients with Crohn’s disease. A: Long segment ileal thickening; B: Mural stratification (arrow) and increased visceral fat (arrowhead); C: Comb sign; D: Axial computed tomography image in a patient with intestinal tuberculosis demonstrating short segment ileocaecal thickening (arrow)with necrotic lymph node (arrowhead); and E: Coronal magnetic resonance image in a patient with intestinal tuberculosis showing ileocaecal thickening (arrowhead) and necrotic lymph node (arrow).

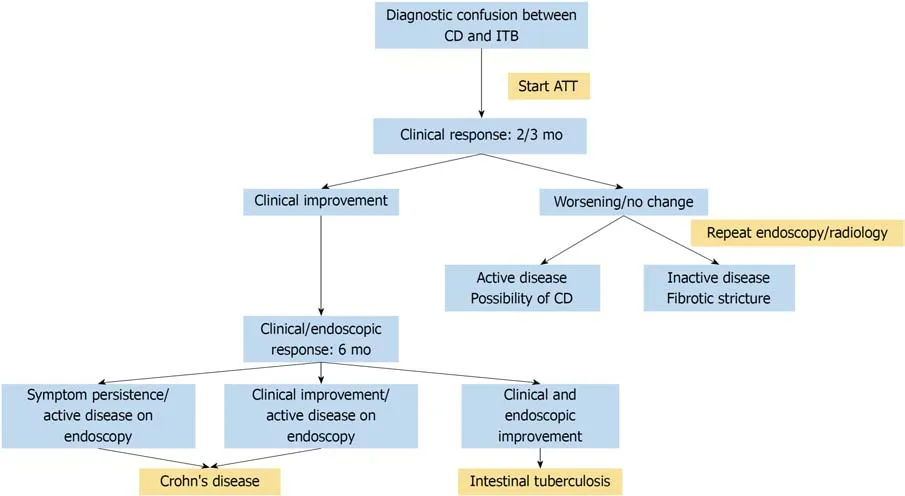

The biggest dilemma after therapeutic ATT trial is the duration of ATT before a patient should be labeled as a non-responder, and the time point when the diagnosis of CD should be considered. In a recent study from our center, of 358 consecutive patients with CD, 135 (38%) had received at least 3 mo of ATT before being finally diagnosed as CD[74]. Their response to ATT was compared with 157 patients with ITB,and by 3 to 6 months, more than 90% of patients with ITB, and up to 38% of patients with CD responded to ATT. However, up to 1-year post-ATT, the patients with ITB sustained their response, whereas, the response to ATT in patients with CD was illsustained and up to 80% patients worsened on follow-up. Moreover, repeat colonoscopy at 6 months of treatment showed mucosal healing in 100% patients with ITB, whereas < 5% of patients with CD had an endoscopic response. Therefore, based upon our results, we propose an algorithm for follow-up of patients on therapeutic ATT trial (Figure 4). The clinical response should be assessed at 2-3 mo of ATT. In patients who are responding, ATT should be continued till 6 months, and at 6 months,a repeat endoscopy should be done to document mucosal healing. Diagnosis of ITB is confirmed in the presence of clinical and endoscopic response. In the presence of no response/worsening on ATT at 2-3 mo, a repeat endoscopic/radiological evaluation should be done, and in the presence of active disease, the diagnosis of CD should be considered.

Multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) would also behave like CD when considering clinical/endoscopic/radiologic non-response to ATT. However, ITB is a paucibacillary disease, and studies from S. Korea and India have shown low prevalence (< 5%) of MDR-TB among patients with ITB[40,75]. A study from Taiwan though reported a prevalence of 13%, a significant proportion of patients in this study had concomitant pulmonary TB, which would have accounted for a higher prevalence of MDR-TB[76]. Therefore, the possibility of MDR-TB remains low in such a situation,however, in the presence of diagnostic features of ITB, and non-response to ATT, the possibility of MDR-TB should be considered.

CONCLUSION

There have been several attempts at solving the seemingly never-ending dilemma ofCD/ITB differentiation, and till date, we have achieved partial success in these attempts because there have been very few parameters which are exclusive for either disease, and these are limited by poor sensitivity. Last few years have seen some new parameters on this aspect, including the latest Bayesian meta-analysis, a new CT based score incorporating CT features and visceral fat, and peripheral blood enumeration of T-regulatory cells. However, none of these parameters have been exclusive and we still need to resort to a therapeutic ATT trial in a significant proportion of patients. Several predictive models have been developed, but are limited by small sample size, complex formulae and lack of validation. Therapeutic ATT trial is also associated with a risk of ATT induced hepatotoxicity, and in a recent report, ATT was the principal reason for the delay in CD diagnosis and this delay was associated with increased risk of long-term complications. Therefore, there is a constant need for a model or a parameter for better differentiation and reduction in the need for an ATT trial. Possible avenues into this complexity of CD/ITB dilemma would be: incorporating the newly developed parameters into a simple model and validating them in other populations across other centers, better approaches to increase the sensitivity of pathologic and microbiologic parameters, and further insights into improved serologic and immunological tests.

Table 6 Features included and the diagnostic accuracy of different multi-parametric predictive models for differentiating Crohn’s disease and intestinal tuberculosis

Figure 4 Algorithm for following a patient on therapeutic anti-tubercular therapy trial. ATT: Anti-tubercular therapy; CD: Crohn’s disease; ITB: Intestinal tuberculosis.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Human immunodeficiency virus and hepatotropic viruses comorbidities as the inducers of liver injury progression

- Esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction: Where are we now in diagnosis and management?

- lnterplay between post-translational cyclooxygenase-2 modifications and the metabolic and proteomic profile in a colorectal cancer cohort

- Adenoma and advanced neoplasia detection rates increase from 45 years of age

- Feasibility of gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection with continuous low-dose aspirin for patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy

- Treatment for gastric ‘indefinite for neoplasm/dysplasia’ lesions based on predictive factors