组蛋白泛素化修饰及其在DNA损伤应答中的作用

2019-01-30张卿义张樱子沈凯张舒羽曹建平

张卿义,张樱子,沈凯,张舒羽,曹建平

组蛋白泛素化修饰及其在DNA损伤应答中的作用

张卿义1,张樱子2,沈凯1,张舒羽2,曹建平2

1. 苏州大学医学部第一临床医学院,苏州 215123 2. 苏州大学医学部放射医学与防护学院,苏州 215123

泛素化修饰是真核生物细胞内重要的翻译后修饰类型,通过调节蛋白质活性、稳定性和亚细胞定位广泛参与细胞内各项信号传导与代谢过程,对维持正常生命活动具有重要意义。组蛋白作为染色质中主要的蛋白成分,与DNA复制转录、修复等行为密切相关,是研究翻译后修饰的热点。DNA损伤后,组蛋白泛素化修饰通过调节核小体结构、激活细胞周期检查点、影响修复因子的招募与装配等诸多途径参与损伤应答。同时,组蛋白泛素化修饰还能调节其他位点翻译后修饰,并通过这种串扰(crosstalk)作用调节DNA损伤应答。本文介绍了组蛋白泛素化修饰的主要位点和相关组分(包括E3连接酶、去泛素化酶与效应分子),以及这些修饰作用共同编译形成的信号网络在DNA损伤应答中的作用,最后总结了目前该领域研究所面临的一些问题,以期为科研人员进一步探索组蛋白密码在DNA损伤应答中的作用提供参考。

组蛋白;泛素化修饰;DNA损伤应答;串扰

DNA是真核生物遗传信息的载体,其遗传保守性是维持物种相对稳定的基础。然而,各种内源性或外源性因素造成的DNA损伤如不能及时修复,将导致细胞凋亡甚至癌变。因此,生物体在进化过程中形成了复杂的DNA损伤应答(DNA damage response, DDR)机制,以应对各种DNA损伤压力。组蛋白是真核生物染色质中主要的蛋白成分,包括H1、H2A、H2B、H3和H4五种类型。约146 bp的DNA通过左手螺旋的方式环绕由2分子H2A-H2B二聚体和1分子H3-H4四聚体组成的核心颗粒1.75圈,形成核小体辅助DNA折叠[1,2]。

组蛋白N端含有大量精氨酸、赖氨酸残基,是主要的翻译后修饰位点。组蛋白在各修饰酶、去修饰酶共同编译下形成组蛋白密码(histone code),构成了DDR中精密的信号网络[3]。近年来,组蛋白泛素化修饰在DDR中的作用愈发受到关注。组蛋白泛素化修饰可以通过调节核小体结构、激活细胞周期检查点、影响修复因子的招募与装配等途径参与DDR。此外,组蛋白修饰之间还存在交互作用,一位点修饰能促进或抑制其他位点的修饰[4,5]。组蛋白泛素化修饰同样可以通过这种串扰(crosstalk)作用调节其他类型翻译后修饰作用于DDR。本文介绍了组蛋白泛素化修饰的各主要位点和相关的E3连接酶、去泛素化酶与效应分子,以及这些修饰作用共同编译形成的信号网络在DDR中的作用。

1 泛素与泛素化修饰

泛素(ubiquitin, ub)是由76个氨基酸组成的多肽,广泛存在于真核生物体内。泛素分子高度保守,在动物、植物和酵母菌中其一级结构仅有1~3个氨基酸残基不同,三级结构基本相同[6]。泛素分子在激活酶(E1)、结合酶(E2)和连接酶(E3)的作用下连接于底物,形成单泛素化修饰。泛素分子还可依次连接于前一泛素分子的赖氨酸或甲硫氨酸残基形成泛素链,称多聚泛素化修饰。连接位点有第6、11、27、29、33、48、63位赖氨酸残基和第1位甲硫氨酸残基(K6/11/27/29/33/48/63-linked and M1-linked) 8种类型。

泛素化修饰是泛素–蛋白酶体途径(ubiquitin- proteasome pathway, UPP)的重要步骤,介导了细胞内短寿蛋白和错误折叠蛋白通过26S蛋白酶体降解。此外,泛素化修饰还能调节蛋白在细胞内的定位与活性,广泛参与DNA复制转录、损伤应答、炎症反应、免疫应答、细胞周期与凋亡、囊泡运输等诸多生理过程[7~11]。不同的效应往往与泛素链不同的拓扑结构有关,例如K11/48连接的泛素链主要参与蛋白质降解,K63连接的泛素链主要参与DNA损伤应答与信号转导,而M1连接的泛素链则主要参与免疫应答与炎症反应[12]。

2 H2A多位点泛素化修饰参与DDR

H2A泛素化修饰最早于1975年发现,首个修饰位点定位于K119 (第119位赖氨酸,同下),后又陆续在K13/15和K127/129等位点发现泛素化修饰[13,14]。H2A各位点泛素化修饰介导多种生物学效应,对修复进程进行调控,在DNA双链断裂(double-strand breaks, DSBs)和紫外线造成的DNA损伤(UV-induced DNA damage)应答中起重要作用。

2.1 沉默损伤周围基因

哺乳动物细胞核内约5%~15%的H2A处于单泛素化修饰状态,其中以H2AK119单泛素化修饰为主。H2AK119单泛素化修饰参与抑制RNA Pol Ⅱ延伸、多梳蛋白家族(polycomb group proteins, PcG)基因沉默、X染色体失活和抑制趋化因子基因表达等诸多生理过程[15~17]。多梳抑制复合体1 (polycomb repressive complex 1, PRC1)是PcG家族成员,其亚基环指蛋白2 (ring finger protein 2, RING2)是单泛素化修饰H2AK119的E3连接酶,通过第98位精氨酸残基嵌入H2A-H2B二聚体间缝隙定位催化反应。由于缺乏活性精氨酸/赖氨酸残基,RING2还需与PRC1另一亚基BMI-1结合形成异二聚体才能充分发挥其催化活性。异二聚体形成有助于稳定E2~ub结构,促进泛素分子传递,BMI-1缺失将严重影响RING2活性[18]。

H2AK119单泛素化修饰可与PcG家族另一成员PRC2催化的H3K27三甲基化修饰相互串扰,即PRC1的CBX亚基识别H3K27三甲基化修饰定位,单泛素化修饰H2AK119;PRC2的JARID2亚基识别H2AK119单泛素化修饰定位,三甲基化修饰H3K27[19]。这种交叉招募可极大地提高损伤位点附近H2AK119单泛素化修饰水平。

近年来,已有关于RING2/BMI-1催化的H2AK119单泛素化修饰参与DSBs修复的研究报道,如在损伤早期调节γH2AX生成、影响修复因子招募以及辅助DNA定位于核仁周围等,但具体机制尚未明确[20,21]。目前,H2AK119 单泛素化修饰在DSBs修复中较为明确的作用是实现损伤位点周围数千碱基对范围内基因沉默,抑制损伤区域的复制、转录行为,减少错误产物的生成,为DNA修复创造条件[22,23]。然而,Chandler等[24]在AsiSI限制酶诱导的DSBs周围并未发现PRC1聚集,对上述理论提出挑战。此外,还有证据表明除参与DSBs修复外,细胞核内储备的K119单泛素化修饰的H2A还可在分子伴侣CAF-1的辅助下定位于UV损伤周围,并通过共济失调毛细血管扩张症Rad3相关蛋白激酶(ATM and Rad3 related kinase, ATR)依赖的途径参与核苷酸切除修复(nucleotide excision repair, NER)后染色质重塑[25,26]。

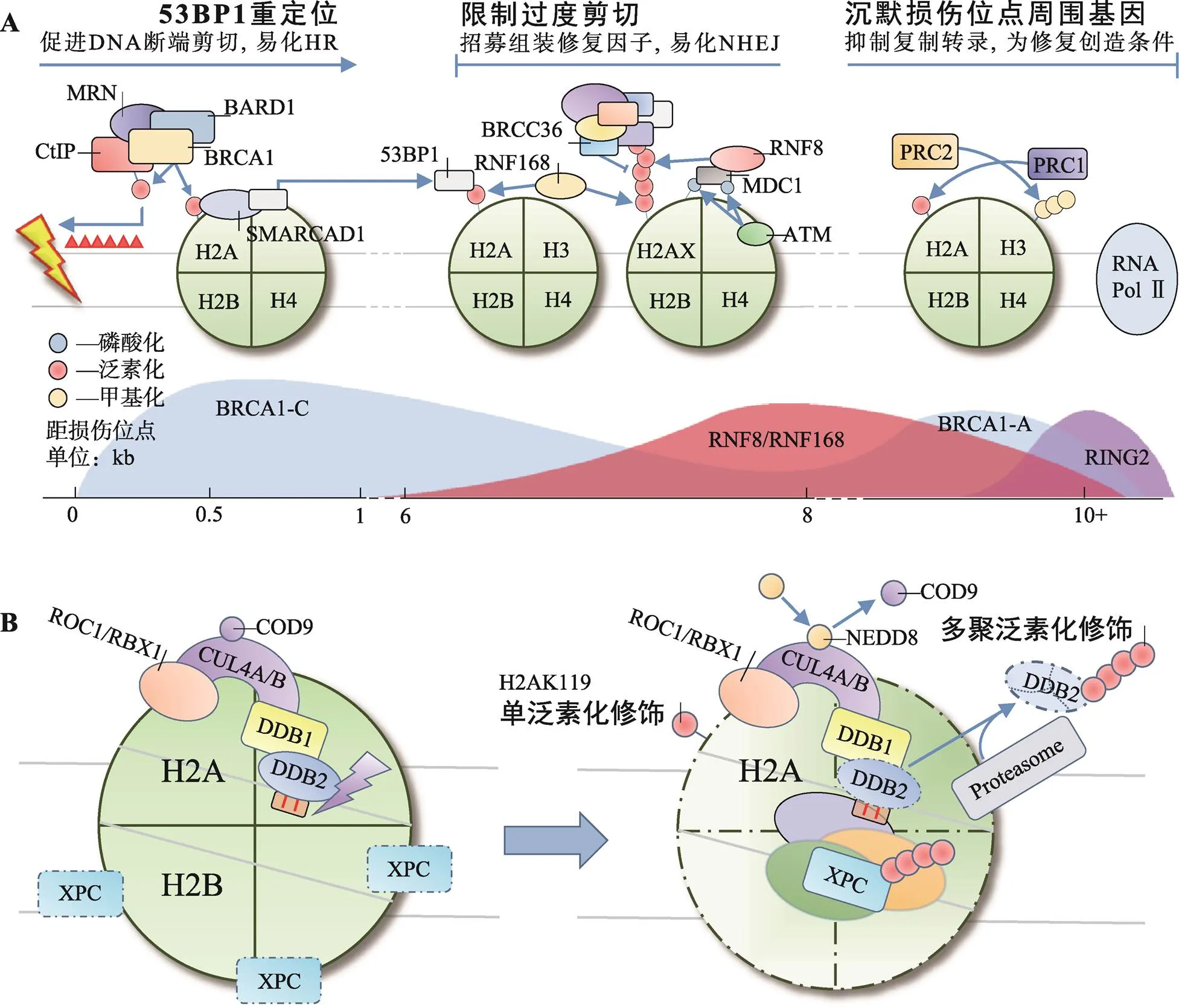

2.2 调节DNA断端剪切

同源重组修复(homologous recombination, HR)和非同源断端连接(non-homologous end joining, NHEJ)是细胞修复DSBs的两种重要方式。BRCA1和53BP1分别是HR和NHEJ中重要的效应分子,二者相互竞争,又彼此协同。BRCA1通过易化DNA断端剪切,促进HR;相反,53BP1则在DNA断端两侧限制DNA剪切长度,防止过度剪切造成的DNA单链复性和染色体重排,易化NHEJ。BRCA1和53BP1在不同位点被招募并级联不同的后续效应,共同决定两种修复方式间的平衡[27](图1A)。

环指蛋白8 (ring finger protein 8, RNF8)和环指蛋白168 (ring finger protein 168, RNF168)催化的H2A/H2AXK13/15泛素化修饰,是BRCA1和53BP1招募过程中的重要信号。RNF8和RNF168的聚集,依赖于ATM和DNA损伤检测点介质1 (mediator of DNA damage checkpoint 1, MDC1)的作用。ATM检测到DSBs后,磷酸化修饰H2AX和MDC1。磷酸化MDC1的BRCT结构域识别γH2AX定位于损伤位点,作为脚手架招募RNF8[28,29]。早期认为由RNF8直接多聚泛素化修饰H2A/H2AXK13/15招募修复因子[30],或首先由RNF8单泛素化修饰H2A/H2AXK13/ 15招募RNF168,再由RNF168延伸K63连接的泛素链招募修复因子[31]。然而实验中发现RNF8在体内对核小体中H2A/H2AX缺乏亲和力,却具有延伸K63连接的泛素链的能力。近年来的研究对这一过程逐渐有了清晰的认识:RNF8被招募至损伤位点后首先多聚泛素化修饰H1(K63连接的泛素链)招募RNF168,由后者单泛素化修饰H2A/H2AXK13/15,最后再由RNF8延伸K63连接的泛素链,招募修复因子[32,33]。

BRCA1是H2A/H2AXK13/15多聚泛素化修饰招募的修复因子之一,实际上BRCA1与RAP80、Abraxas、MERIT40、BRCC36、BRCC45和BARD1形成BRCA-A复合体共同被招募[34]。该复合体以Abraxas为核心组装,RAP80负责识别泛素链定位[35]。BRCA1-A复合体能限制DNA断端剪切,防止HR过度激活[34]。去泛素化酶BRCC36清除K63连接的泛素链,被认为在该过程中发挥主要作用[36]。53BP1是另一个被招募的修复因子,与BRCA1不同,53BP1通过识别H2AK15单泛素化修饰定位[37,38]。53BP1可在损伤位点与剪切酶竞争,调整DNA断端剪切长度。同时,53BP1还可作为脚手架,促进修复因子组装[39]。BRCA1-A复合体和53BP1的协同作用有效避免了DNA断端过度剪切,使细胞倾向于通过NHEJ途径修复DSBs。

K127/129单泛素化修饰是新近发现的第3个参与DSBs修复的H2A泛素化修饰类型,由BRCA1-C复合体催化。BRCA1-C复合体包含BRCA1/BARD1二聚体、DNA内切酶CtIP和MRN复合体3种成分,BRCA1是主要的E3活性单位[40]。与RING2/BMI-1二聚体相似,BRCA1需与BARD1结合才能充分发挥其催化活性[41]。BRCA1/BARD1在异染色质蛋白HP1的辅助下定位至损伤中心区域催化H2AK127/ 129单泛素化修饰,后者可被SMARCAD1的CUE结构域识别[42]。SMARCAD1依赖其ATP酶活性将53BP1重新定位于损伤外围,易化CtIP在MRN复合体辅助下剪切DNA断端,促进以高保真的HR修复DSBs[41,43~45]。值得一提的是,BRCA1还可形成BRCA1-B/D复合体,分别通过调节细胞周期和促进链侵入的方式参与DDR[34]。

图1 H2A各位点泛素化修饰在HR/NHEJ与NER中的作用

A:H2A多位点泛素化修饰共同参与DSBs修复;B:H2AK119单泛素化修饰参与NER。

2.3 辅助起始NER

除RING2/BMI-1外,H2AK119单泛素化修饰还可由DDB1-CUL4DDB2复合体催化,辅助起始NER[46]。NER是应对UV造成的DNA损伤的主要方式,除修复环丁烷嘧啶二聚体(cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers, CPDs)和6-4光产物[(6-4) photoproducts, 6-4 PPs]外,NER还可广泛地识别多种损伤,与其特殊的识别机制有关。XPC是全基因组NER中主要的识别因子,可识别DNA发生修饰(损伤)且Waston-Crick碱基配对破坏时形成的不稳定结构,而非损伤本身[47]。CPDs本身不足以引起DNA螺旋结构的不稳定,因此还需DDB1-CUL4DDB2复合体的辅助才能激活NER。该复合体由E3连接酶CUL4和紫外线损伤DNA结合蛋白(UV-damaged DNA-binding protein, UV-DDB)组成,其中UV-DDB包括DDB1与DDB2两种类型,DDB1位于CUL4的N端,是连接CUL4与DDB2的桥梁。DDB2通过WD40结构域识别CPDs后招募DDB1-CUL4至损伤位点[48]。正常情况下,CUL4的活性受COP9信号体抑制,激活则依赖NEDD8类泛素化修饰[49]。

正常细胞在UV损伤后H2AK119单泛素化修饰水平迅速下降,DDB1-CUL4DD2复合体在H2AK119单泛素化修饰水平的恢复中起重要作用。H2AK119单泛素化修饰能有效促进H2A/H2A-H2B从核小体解离,加剧DNA螺旋结构的不稳定性,促进XPC识别[50]。同时,DDB2、XPC均是DDB1- CUL4DDB2泛素化修饰的底物,DDB2泛素化修饰后可被分子伴侣VCP/p97识别,介导DDB2通过UPP降解,解除位阻效应,促进后续NER进程[51,52]。XPC泛素化修饰可增强其与DNA的亲和力,促进其与损伤DNA结合[52,53](图1B)。

目前认为,DDB1-CUL4DDB2单泛素化修饰H2AK119是发生在NER早期的事件,辅助XPC对损伤DNA的识别,激活NER。RING2/BMI-1单泛素化修饰H2AK119则更多的以剪切后事件的形式发生于NER后期,通过CAF-1和ATR依赖的途径参与染色质重塑[25,26]。

3 H2B单泛素化修饰串扰其他修饰

RNF20-RNF40催化的H2BK120单泛素化修饰是参与哺乳动物DDR的主要类型[54]。在正常细胞中,H2BK120单泛素化修饰还参与了基因转录的起始、延伸和转录后mRNA的剪切,并能选择性地促进或抑制基因的表达[55~57]。转录相关的H2BK120单泛素化修饰高背景为研究H2B泛素化修饰在DDR中的作用提高了难度,直至2011年Moyal等[58]才证实DNA损伤可提高局部H2BK120单泛素化修饰水平,确认了H2BK120单泛素化修饰同样参与DDR。

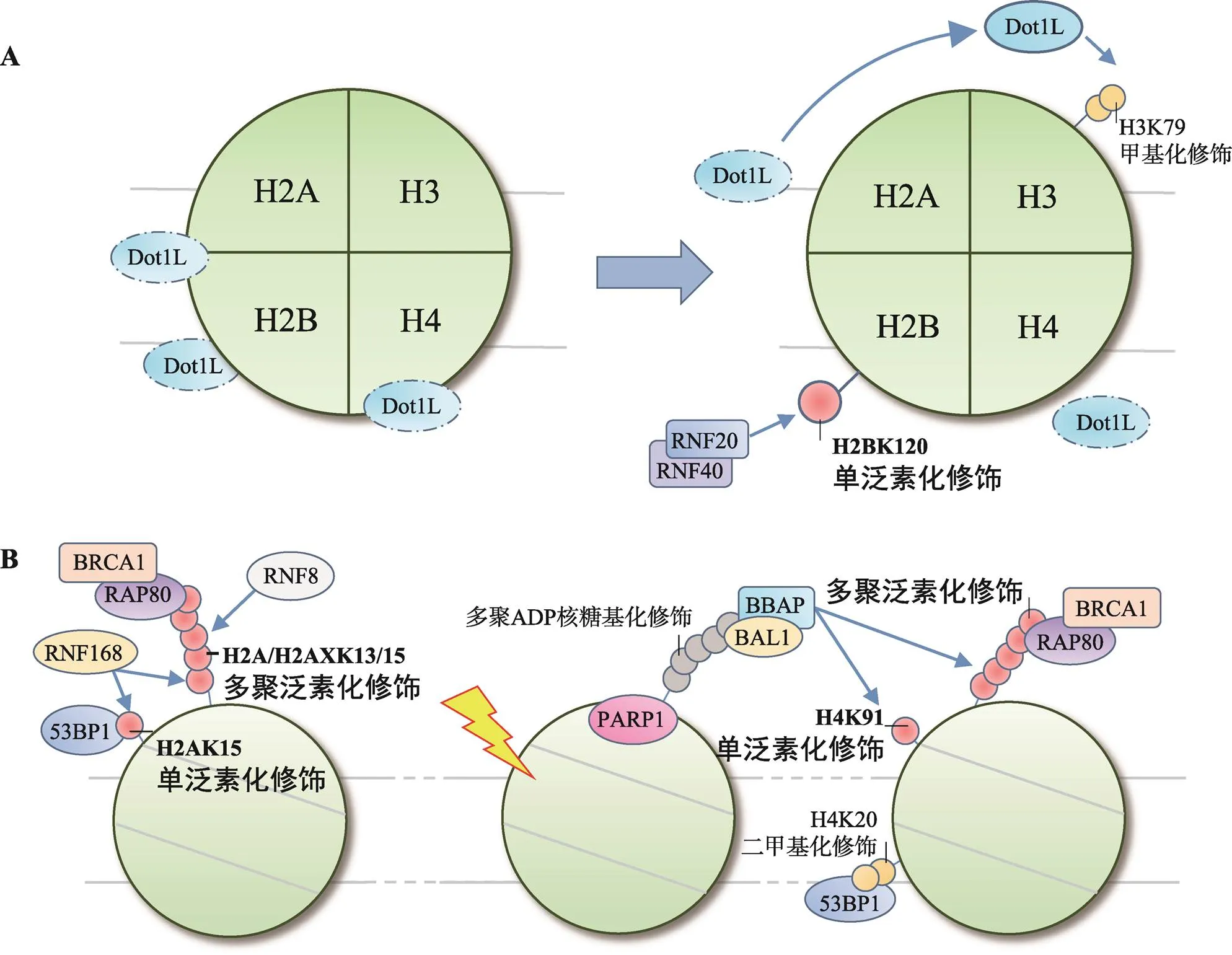

H2BK120单泛素化修饰参与DDR,与组蛋白翻译后修饰间的串扰作用密切相关。以串扰H3K79甲基化修饰为例,H2BK120单泛素化修饰能促进H3K79甲基化修饰,特别是H3K79二甲基化修饰,对53BP1等修复因子的招募具有重要意义[59,60]。关于H2BK120单泛素化修饰是如何串扰H3K79甲基化修饰的,Zhou等[61]提出了“占位诱导”学说,即H2BK120单泛素化修饰在空间上封闭核小体表面无功能位点,促进类端粒沉默干扰体1 (disruptor of telomeric silencing 1-like, Dot1L)在效应位点聚集并甲基化修饰H3K79。同时,H2BK120单泛素化修饰通过串扰作用还能改变染色质高度压缩的结构,例如串扰H3K4甲基化修饰可协同染色质重塑因子SNF2h调节核小体结构[62,63];串扰H4K16乙酰化修饰可开放约30 nm长度的染色质纤维[64,65];串扰H3K56乙酰化修饰同样可以促进促转录因子复合体FACT调节染色质结构,为修复因子装配提供条件[66,67]。

相似的作用同样存在于酵母菌中,由E3连接酶Bre1催化的H2BK123单泛素化修饰同样可以提高Dot1甲基化修饰H3K79的效率,促进53BP1、Ku80和XRCC4的招募[68,69]。同时,H3K79甲基化修饰还可作为修复因子的停靠位点参与NER[70]。H2BK123单泛素化修饰还参与了复制过程中DNA损伤耐受机制的调控,可能同样与调节核小体结构,促进复制叉恢复与缺损区段DNA的填补有关[71,72]。

另一方面,H2BK120单泛素化修饰在DDR中的作用还体现在激活细胞周期检查点中。Kari等[66]敲除RNF40并采用新制霉菌素处理细胞后发现,与对照组相比,G2/M:G1从5.02下降至2.29,S期占比从2.93%升至5.66%,提出H2BK120单泛素化修饰对细胞周期检查点的激活和维持具有重要作用。但Moyal等[58]在实验中沉默RNF20后并未发现细胞周期检查点激活异常,认为RNF20-RNF40并非通过激活细胞周期检查点的方式参与DDR。上述差异可能与分别沉默RNF40和RNF20有关,其具体作用还有待进一步研究。

4 H3、H4泛素化修饰协同参与DDR

正常生理状态下细胞内仅有约0.3%的H3和0.1%的H4处于泛素化修饰状态。UV损伤后,H3、H4泛素化修饰水平迅速升高,并于1~2 h内达到峰值[73]。

Wang等[73]通过层析与质谱分析,提纯并确认了泛素化修饰H3和H4的E3连接酶复合体——CUL4- DDB-ROC1 (即DDB1-CUL4DDB2复合体)。UV损伤后,泛素化修饰的H3在胞浆和核浆中比例分别从5%升至19%,12%升至40%;相应地,在核颗粒中的比例从83%跌至41%,表明泛素化修饰可促进H3从核小体解离,易化XPC识别,激活NER[73]。除上述作用外,CUL4-DDB-ROC1复合体还可促进NER后H3K56乙酰化修饰水平恢复,促进核小体组装[74];以及在修复前辅助H3.3在损伤部位沉积,为修复后转录恢复打下基础[75]。

通常认为,组蛋白修饰位点位于伸出核小体外的肽链N端,但近年来研究发现组蛋白核心区域也是翻译后修饰的热点部位[76]。H4K91处于H2A-H2B二聚体与H3-H4四聚体连接的核心区域,可由B细胞淋巴瘤和BAL相关蛋白(B-lymphoma and BAL- associated protein, BBAP)单泛素化修饰。H4K91单泛素化修饰可串扰H4K20甲基化修饰影响53BP1的招募[77]。实验表明H4K91单泛素化修饰可以提高赖氨酸甲基转移酶PR-Set7/Set8的聚集效率,促进H4K20二甲基化修饰。BBAP敲除后,53BP1在损伤部位的聚集显著降低。

此外,BBAP还可通过多聚泛素化修饰底物招募修复因子,并且这是一种独立于RNF8/RNF168轴介导的H2A/H2AXK13/15多聚泛素化修饰的招募模式[63]。该过程中,多聚ADP-核糖聚合酶1 [poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1, PARP1]首先识别DNA损伤,在损伤部位多聚ADP-核糖基化修饰底物,后者可被BBAP在BAL1的辅助下识别并定位,再由BBAP催化产生泛素链,招募BRCA1等修复因子[78](图2B)。分析认为,BBAP催化的多聚泛素化修饰发生于DNA损伤早期,较RNF8/RNF168催化的H2A/H2AXK13/15多聚泛素化修饰更为简单快捷。

图2 H2B和H4泛素化修饰在DNA损伤应答中的作用

A: H2BK120单泛素化修饰串扰H3K79甲基化修饰;B: H4泛素化修饰招募修复因子。

5 组蛋白去泛素化修饰

组蛋白密码编译过程中,修饰与去修饰总是对应存在的。无一例外地,DDR过程中泛素化修饰也必然伴随着去泛素化修饰。上调去泛素化酶(deubiquitinating enzymes, DUBs)能抑制修复因子的招募,延缓DDR进程;下调DUBs则引起自发性染色体断裂,更加强调了泛素化修饰与去泛素化修饰间动态平衡在维持基因组稳定性中的重要性[79]。

泛素特异性蛋白酶(ubiquitin-specific proteases, USPs)是DUBs家族中成员最多的一类。USPs的3个结构域空间构象类似于“手指-手掌-拇指”(fingers-palm-thumb),其中palm和thumb构成活性中心,fingers负责定位[80]。H2AK119可由USP16去泛素化修饰,USP16敲除将抑制修复完成后转录的重启[22,81]。BAP1是另一个作用于H2AK119的DUB,其C端与核小体结合,可在ASXL1的辅助下完成去泛素化修饰[82]。在最新的研究中,Jullien等[83]还发现USP21亦能解除H2AK119单泛素化修饰产生的基因抵抗作用。USP3、USP51均是参与H2A/H2AXK13/15去泛素修饰的DUBs,区别在于USP3过表达能降低RNF168在损伤位点的招募[84];而USP51依赖于RNF168定位,过表达仅影响RNF168下游修复因子如53BP1、BRCA1的招募,不影响上游分子ATM、MDC1、RNF168的聚集[85]。USP3、USP51产生不同效应或与拮抗不同的E3连接酶有关:USP3可能直接拮抗RNF8,抑制H1多聚泛素化修饰而影响RNF168的招募及后续修饰,USP51则可能与RNF168拮抗,影响H2A/H2AXK13/ 15单泛素化修饰。USP48是新近发现的DUB,去泛素化修饰H2AK127/129,通过限制MARCAD1对53BP1的重定位限制DNA断端的剪切,对HR起负性调控作用[86]。值得注意的是,USP48的激活还需H2A上其他位点泛素化修饰的辅助,可能与改变USP48构象形成活性中心有关[86]。

转录辅助复合体SAGA是参与DDR过程中H2BK120 (H2BK123)去泛素化修饰的DUB。在哺乳动物中SAGA亚基USP22起主要催化作用,而在酵母菌中以Ubp8为主[87]。实验表明敲除USP22将严重影响细胞通过HR或NHEJ修复DSBs,表明H2BK120去泛素化修饰在DDR中同样起重要作用[88]。

6 结语与展望

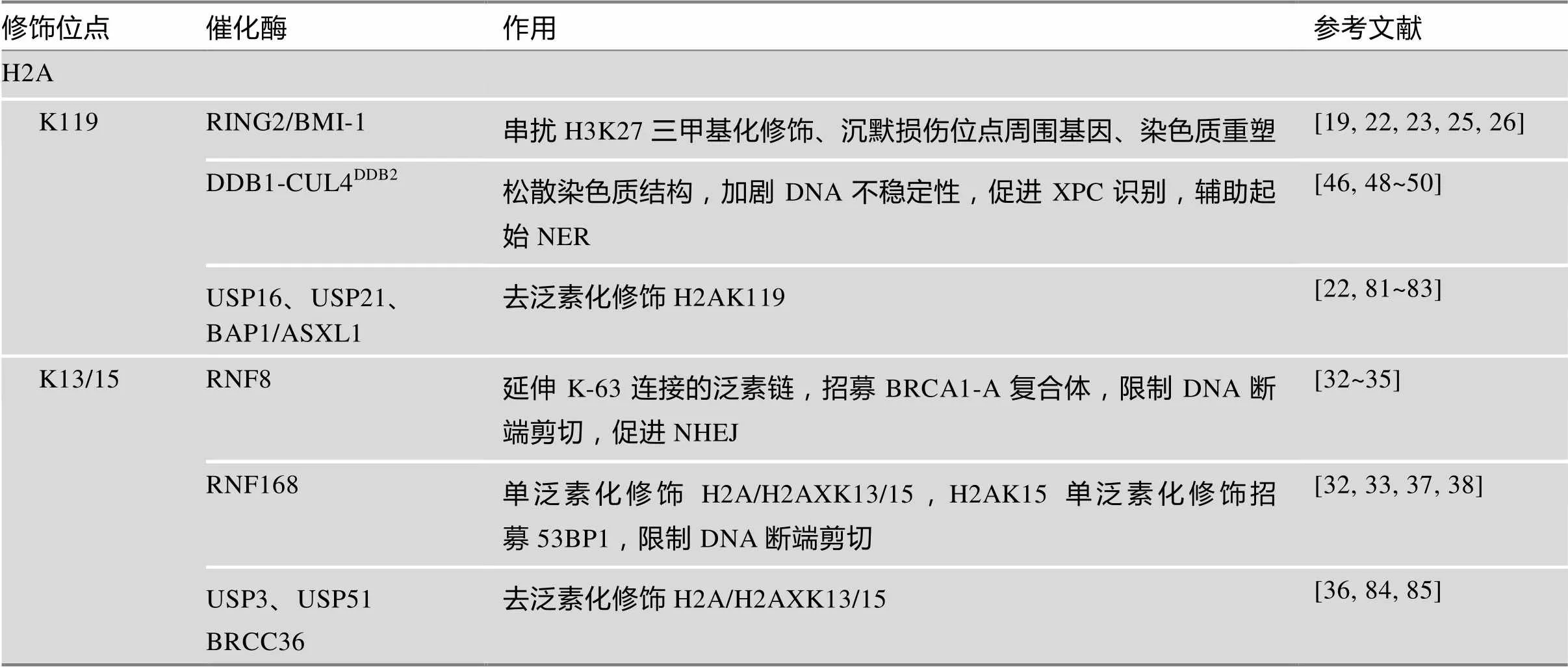

DDR是一个复杂的过程,涵盖了损伤位点的识别、细胞周期检查点激活、DNA修复和染色质重塑等诸多环节,组蛋白翻译后修饰在该过程中扮演重要角色。本文总结了组蛋白泛素化修饰/去泛素化修饰的各位点和相关组分,以及这些修饰作用共同编译形成的信号网络在DDR中的作用(表1)。

近年来,人们对于组蛋白泛素化修饰在DDR中的作用有了深入的了解。这得益于研究手段的进步与高度特异性抗体的制备,使人们能够排除高背景的干扰,直接观察局部DNA损伤后细胞的应答情况[58]。方法的创新也同样至关重要,在组蛋白上人为连接泛素分子为探究位阻效应在组蛋白翻译后修饰间的串扰作用提供了新的思路[61,68]。然而,现阶段的研究还存在一定的问题:某些泛素化修饰的位点、类型尚未确定[77];某些泛素化修饰的具体作用仍不够清晰[40];泛素化与去泛素化修饰间关系混乱[79];与其他翻译后修饰间串扰的具体作用及机制不明等。此外,从现有的研究来看,仍有其他泛素化修饰位点尚未发现[86]。对于上述问题的深入研究,必将为全面系统地阐述组蛋白密码在DDR中的作用奠定坚实的基础。

表1 组蛋白泛素化/去泛素化修饰在DNA损伤应答中的作用

续表

?表示修饰位点暂不明确。

[1] Mariñoramírez L, Kann MG, Shoemaker BA, Landsman D. Histone structure and nucleosome stability., 2005, 2(5): 719–729.

[2] Luger K, Mäder AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 Å resolution., 1997, 389(6648): 251–260.

[3] Strahl BD, Allis CD. The language of covalent histone modifications., 2000, 403(6765): 41–45.

[4] Suganuma T, Workman JL. Crosstalk among histone modifications., 2008, 135(4): 604–607.

[5] Lee JS, Smith E, Shilatifard A. The language of histone crosstalk., 2010, 142(5): 682–685.

[6] Hershko A, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system., 1998, 67(1): 425–479.

[7] Herrmann J, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins in protein regulation., 2007, 100(9): 1276–1291.

[8] Shaid S, Brandts CH, Serve H, Dikic I. Ubiquitination and selective autophagy., 2013, 20(1): 21–30.

[9] Wagner SA, Beli P, Weinert BT, Nielsen ML, Cox J, Mann M, Choudhary C. A proteome-wide, quantitative survey ofubiquitylation sites reveals widespread regulatory roles., 2011, 10(10): M111.013284.

[10] Welchman RL, Gordon C, Mayer RJ. Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins as multifunctional signals., 2005, 6(8): 599–609.

[11] Schnell JD, Hicke L. Non-traditional functions of ubiquitin and ubiquitin-binding proteins., 2003, 278(38): 35857–35860.

[12] Komander D, Rape M. The Ubiquitin Code., 2012, 81: 203–229.

[13] Goldknopf IL, Taylor CW, Baum RM, Yeoman LC, Olson MO, Prestayko AW, Busch H. Isolation and characterization of protein A24, a "histone-like" non-histone chromosomal protein., 1975, 250(18): 7182– 7187.

[14] Goldknopf IL, Busch H. Isopeptide linkage between nonhistone and histone 2A polypeptides of chromosomal conjugate-protein A24., 1977, 74(3): 864–868.

[15] Wang H, Wang L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Vidal M, Tempst P, Jones RS, Zhang Y. Role of histone H2A ubiquitination in polycomb silencing., 2004, 431 (7010): 873–878.

[16] Fang J, Chen TB, Li E, Zhang Y. Ring1b-mediated H2A ubiquitination associates with inactive X chromosomes and is involved in initiation of X inactivation., 2004, 279(51): 52812–52815.

[17] Zhou W, Zhu P, Wang J, Pascual G, Ohgi KA, Lozach J, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Histone H2A monoubiquitination represses transcription by inhibiting RNA polymerrase II transcriptional elongation., 2008, 29(1): 69–80.

[18] Ginjala V, Nacerddine K, Kulkarni A, Oza J, Hill SJ, Yao M, Citterio E, Lohuizen MV, Ganesan S. BMI1 is recruited to DNA breaks and contributes to DNA damage-induced H2A ubiquitination and repair., 2011, 31(10): 1972–1982.

[19] Blackledge NP, Farcas AM, Kondo T, King HW, McGouran JF, Hanssen LL, Ito S, Cooper S, Kondo K, Koseki Y, Ishikura T, Long HK, Sheahan TW, Brockdorff N, Kessler BM, Koseki H, Klose RJ. Variant PRC1 complex-dependent H2A ubiquitylation drives PRC2 recruitment and polycomb domain formation., 2014, 157(6): 1445–1459.

[20] Ismail IH, Andrin C, Mcdonald D, Hendzel MJ. BMI1- mediated histone ubiquitylation promotes DNA double- strand break repair., 2010, 191(1): 45–60.

[21] Chitale S, Richly H. Nuclear organization of nucleotide excision repair is mediated by RING1B dependent H2A- ubiquitylation., 2017, 8(19): 30870–30887.

[22] Shanbhag NM, Rafalska-Metcalf IU, Balane-Bolivar C, Janicki SM, Greenberg RA. ATM-dependent chromatin changes silence transcription in cis to DNA double-strand breaks., 2010, 141(6): 970–981.

[23] Kakarougkas A, Ismail A, Chambers AL, Riballo E, Herbert AD, Künzel J, Löbrich M, Jeggo PA, Downs JA. Requirement for PBAF in transcriptional repression and repair at DNA breaks in actively transcribed regions of chromatin., 2014, 55(5): 723–732.

[24] Chandler H, Patel H, Palermo R, Brookes S, Matthews N, Peters G. Role of polycomb group proteins in the DNA damage response – a reassessment., 2014, 9(7): e102968.

[25] Bergink S, Salomons FA, Hoogstraten D, Groothuis TA, De WH, Wu J, Yuan L, Citterio E, Houtsmuller AB, Neefjes J, Hoeijmakers JH , Vermeulen W , Dantuma NP. DNA damage triggers nucleotide excision repair-dependent monoubiquitylation of histone H2A., 2006, 20(10): 1343–1352.

[26] Zhu Q, Wani G, Arab HH, El-Mahdy MA, Ray A, Wani AA. Chromatin restoration following nucleotide excision repair involves the incorporation of ubiquitinated H2A at damaged genomic sites., 2009, 8(2): 262– 273.

[27] Uckelmann M, Sixma TK. Histone ubiquitination in the DNA damage response., 2017, 56: 92–101.

[28] Stucki M, Clapperton JA, Mohammad D, Yaffe MB, Smerdon SJ, Jackson SP. MDC1 directly binds phosphorrylated histone H2AX to regulate cellular responses to DNA double-strand breaks., 2005, 123(7): 1213– 1226.

[29] Huen MS, Grant R, Manke I, Minn K, Yu X, Yaffe MB, Chen J.transduces the DNA-damage signal via histone ubiquitylation and checkpoint protein assembly., 2007, 131(5): 901–914.

[30] Mailand N, Bekker-Jensen S, Faustrup H, Melander F, Bartek J, Lukas C, Lukas J.ubiquitylates histones at DNA double-strand breaks and promotes assembly of repair proteins., 2007, 131(5): 887–900.

[31] Doil C, Mailand N, Bekker-Jensen S, Menard P, Larsen DH, Pepperkok R, Ellenberg J, Panier S, Durocher D, Bartek J.binds and amplifies ubiquitin conjugates on damaged chromosomes to allow accumulation of repair proteins., 2009, 136(3): 435–446.

[32] Mattiroli F, Vissers JH, van Dijk WJ, Ikpa P, Citterio E, Vermeulen W, Marteijn JA, Sixma TK. RNF168 ubiquitinateson H2A/H2AX to drive DNA damage signaling., 2012, 150(6): 1182–1195.

[33] Thorslund T, Ripplinger A, Hoffmann S, Wild T, Uckelmann M, Villumsen B, Narita T, Sixma TK, Choudhary C, Bekkerjensen S, Mailand N. Histone H1 couples initiation and amplification of ubiquitin signalling after DNA damage., 2015, 527(7578): 389–393.

[34] Savage KI, Harkin DP. BRCA1, a 'complex' protein involved in the maintenance of genomic stability., 2015, 282(4): 630–646.

[35] Sobhian B, Shao G, Lilli DR, Culhane AC, Moreau LA, Xia B, Livingston DM, Greenberg RA. RAP80 targets BRCA1 to specific ubiquitin structures at DNA damage sites., 2007, 316(5828): 1198–1202.

[36] Ng HM, Wei LZ, Lan L, Huen MSY. The Lys63- deubiquitylating enzyme BRCC36 limits DNA break processing and repair., 2016, 291(31): 16197–16207.

[37] Fradetturcotte A, Canny MD, Escribanodíaz C, Orthwein A, Leung CC, Huang H, Landry MC, Kitevskileblanc J, Noordermeer SM, Sicheri F, Durocher D. 53BP1 is a reader of the DNA-damage-induced H2A lys 15 ubiquitin mark., 2013, 499(7456): 50–54.

[38] Wilson MD, Benlekbir S, Fradet-Turcotte A, Sherker A, Julien JP, Mcewan A, Noordermeer SM, Sicheri F, Rubinstein JL, Durocher D. The structural basis of modified nucleosome recognition by., 2016, 536(7614): 100–103.

[39] Ochs F, Somyajit K, Altmeyer M, Rask MB, Lukas J, Lukas C. 53BP1 fosters fidelity of homology-directed DNA repair., 2016, 23(8): 714–721.

[40] Kalb R, Mallery D, Larkin C, Huang JJ, Hiom K. BRCA1 is a histone-H2A-specific ubiquitin ligase., 2014, 8(4): 999–1005.

[41] Densham RM, Morris JR. The BRCA1 ubiquitin ligase function sets a new trend for remodelling in DNA repair., 2017, 8(2): 116–125.

[42] Densham RM, Garvin AJ, Stone HR, Strachan J, Baldock RA, Daza-Martin M, Fletcher A, Blair-Reid S, Beesley J, Johal B, Pearl LH, Neely R, Keep NH, Watts FZ, Morris JR. Human BRCA1–BARD1 ubiquitin ligase activity counteracts chromatin barriers to DNA resection., 2016, 23(7): 647–655.

[43] Gieni RS, Ismail IH, Campbell S, Hendzel MJ. Polycomb group proteins in the DNA damage response: a link between radiation resistance and "stemness"., 2011, 10(6): 883–894.

[44] Cruz-García A, López-Saavedra A, Huertas P. BRCA1 accelerates CtIP-mediated DNA-end resection., 2014, 9(2): 451–459.

[45] Polato F, Callen E, Wong N , Faryabi R, Bunting S, Chen HT, Kozak M, Kruhlak MJ, Reczek CR, Lee WH, Ludwig T, Baer R, Feigenbaum L, Jackson S, Nussenzweig A. CtIP-mediated resection is essential for viability and can operate independently of BRCA1., 2014, 211(6): 1027–1036.

[46] Hannah J, Zhou P. Distinct and overlapping functions of the cullin E3 ligase scaffolding proteins CUL4A and CUL4B., 2015, 573(1): 33–45.

[47] Hess MT, Schwitter U, Petretta M, Giese B, Naegeli H. Bipartite substrate discrimination by human nucleotide excision repair., 1997, 94(13): 6664–6669.

[48] Lan L, Nakajima S, Kapetanaki MG, Hsieh CL, Fagerburg M, Thickman K, Rodriguez-Collazo P, Leuba SH, Levine AS, Rapić-Otrin V. Monoubiquitinated histone H2A destabilizes photolesion-containing nucleosomes with concomitant release of UV-damaged DNA-binding protein E3 ligase., 2012, 287(15): 12036–12049.

[49] Hannah J, Zhou P. Regulation of DNA damage response pathways by the cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases., 2009, 8(4): 536–543.

[50] Kapetanaki MG, Guerrero-Santoro J, Bisi DC, Hsieh CL, Rapić-Otrin V, Levine AS. The DDB1-CUL4ADDB2ubiquitin ligase is deficient in xeroderma pigmentosum group E and targets histone H2A at UV-damaged DNA sites., 2006, 103(8): 2588–2593.

[51] Puumalainen MR, Lessel D, Rüthemann P, Kaczmarek N, Bachmann K, Ramadan K, Naegeli H. Chromatin retention of DNA damage sensors DDB2 and XPC through loss of p97 segregase causes genotoxicity., 2014, 5: 3695.

[52] El-Mahdy MA, Zhu Q, Wang QE, Wani G, Praetorius-Ibba M, Wani AA. Cullin 4A-mediated proteolysis of DDB2 protein at DNA damage sites regulateslesion recognition by XPC., 2006, 281(19): 13404– 13411.

[53] Sugasawa K, Okuda Y, Saijo M, Nishi R, Matsuda N, Chu G, Mori T, Iwai S, Tanaka K, Tanaka K, Hanaoka F. UV-induced ubiquitylation of XPC protein mediated by UV-DDB-ubiquitin ligase complex., 2005, 121(3): 387–400.

[54] Meas R, Mao P. Histone ubiquitylation and its roles in transcription and DNA damage response., 2015, 36: 36–42.

[55] Shiloh Y, Shema E, Moyal L, Oren M. RNF20-RNF40: A ubiquitin-driven link between gene expression and the DNA damage response., 2011, 585(18): 2795–2802.

[56] Hérissant L, Moehle EA, Bertaccini D, Dorsselaer AV, Schaefferreiss C, Guthrie C, Dargemont C. H2B ubiquitylation modulates spliceosome assembly and function in budding yeast., 2014, 106(4): 126–138.

[57] Weake VM, Workman JL. Histone ubiquitination: triggering gene activity., 2008, 29(6): 653–663.

[58] Moyal L, Lerenthal Y, Gana-Weisz M, Mass G, So S, Wang SY, Eppink B, Chung YM, Shalev G, Shema E, Shkedy D, Smorodinsky NI, van Vliet N, Kuster B, Mann M, Ciechanover A, Dahm-Daphi J, Kanaar R, Hu MC, Chen DJ, Oren M, Shiloh Y. Requirement of ATM- dependent monoubiquitylation of histone H2B for timely repair of DNA double-strand breaks., 2011, 41(5): 529–542.

[59] Huyen Y, Zgheib O, Ditullio RA, Gorgoulis VG, Zacharatos P, Petty TJ, Sheston EA, Mellert HS, Stavridi ES, Halazonetis TD. Methylated lysine 79 of histone H3 targets 53BP1 to DNA double-strand breaks., 2004, 432(7015): 406–411.

[60] Wakeman TP, Wang Q, Feng J, Wang XF. Bat3 facilitates H3K79 dimethylation by DOT1L and promotes DNA damage-induced 53BP1 foci at G1/G2 cell-cycle phases., 2012, 31(9): 2169–2181.

[61] Zhou LJ, Holt MT, Ohashi N, Zhao AS, Muller MM, Wang BY, Muir TW. Evidence that ubiquitylated H2B corrals hDot1L on the nucleosomal surface to induce H3K79 methylation., 2016, 7:10589.

[62] Kato A, Komatsu K. RNF20-SNF2H pathway of chromatin relaxation in DNA double-strand break repair., 2015, 6(3): 592–606.

[63] Kim J, Guermah M, McGinty RK, Lee J-S, Tang Z, Milne TA, Shilatifard A, Muir TW, Roeder RG. RAD6-mediated transcription-coupled H2B ubiquitylation directly stimulates H3K4 methylation in human cells., 2009, 137(3): 459–471.

[64] Fierz B, Chatterjee C, McGinty RK, Bar-Dagan M, Raleigh DP, Muir TW. Histone H2B ubiquitylation disrupts local and higher-order chromatin compaction., 2011, 7(2): 113–119.

[65] Robinson PJJ, An W, Routh A, Martino F, Chapman L, Roeder RG, Rhodes D. 30 nm chromatin fibre decompaction requires both H4-K16 acetylation and linker histone eviction., 2008, 381(4): 816–825.

[66] Kari V, Shchebet A, Neumann H, Johnsen SA. The H2B ubiquitin ligase RNF40 cooperates with SUPT16H to induce dynamic changes in chromatin structure during DNA double-strand break repair., 2011, 10(20): 3495–3504.

[67] Nair DM, Ge Z, Mersfelder EL, Parthun MR. Genetic interactions between POB3 and the acetylation of newly synthesized histones., 2011, 57(4): 271–286.

[68] Vlaming H, van Welsem T, de Graaf EL, Ontoso D, Altelaar AF, San-Segundo PA, Heck AJ, van Leeuwen F. Flexibility in crosstalk between H2B ubiquitination and H3 methylation in vivo., 2014, 15(10): 1077– 1084.

[69] Nakanishi S, Lee JS, Gardner KE, Gardner JM, Takahashi Y, Chandrasekharan MB, Sun ZW, Osley MA, Strahl BD, Jaspersen SL, Shilatifard A. Histone H2BK123 monoubiquitination is the critical determinant for H3K4 and H3K79 trimethylation by COMPASS and Dot1., 2009, 186(3): 371–377.

[70] Tatum D, Li S. Evidence that the histone methyltransferase Dot1 mediates global genomic repair by methylating histone H3 on lysine 79., 2011, 286(20): 17530–17535.

[71] Hung SH, Wong RP, Ulrich HD, Kao CF. Monoubiquitylation of histone H2B contributes to the bypass of DNA damage during and after DNA replication., 2017, 114(11): E2205–E2214.

[72] Northam MR, Trujillo KM. Histone H2B mono- ubiquitylation maintains genomic integrity at stalled replication forks., 2016, 44(19): 9245–9255.

[73] Wang H, Zhai L, Xu J, Joo HY, Jackson S, Erdjument- Bromage H, Tempst P, Xiong Y, Zhang Y. Histone H3 and H4 ubiquitylation by the CUL4-DDB-ROC1 ubiquitin ligase facilitates cellular response to DNA damage., 2006, 22(3): 383–394.

[74] Zhu QZ, Wei SC, Sharma N, Wani G, He JS, Wani AA. Human CRL4DDB2ubiquitin ligase preferentially regulates post-repair chromatin restoration of H3K56Ac through recruitment of histone chaperon CAF-1., 2017, 8(61): 104525–104542.

[75] Adam S, Polo SE, Almouzni G. Transcription recovery after DNA damage requires chromatin priming by the H3.3 histone chaperone HIRA., 2013, 155(1): 94– 106.

[76] Tropberger P, Schneider R. Scratching the (lateral) surface of chromatin regulation by histone modifications., 2013, 20(6): 657–661.

[77] Yan Q, Dutt S, Xu R, Graves K, Juszczynski P, Manis JP, Shipp MA. BBAP monoubiquitylates histone H4 at lysine 91 and selectively modulates the DNA damage response., 2009, 36(1): 110–120.

[78] Yan Q, Xu R, Zhu L, Cheng X, Wang Z, Manis J, Shipp MA. BAL1 and its partner E3 ligase, BBAP, link poly (ADP-ribose) activation, ubiquitylation, and double-strand DNA repair independent of ATM, MDC1, and RNF8., 2013, 33(4): 845–857.

[79] Lancini C, van den Berk PC, Vissers JH, Gargiulo G, Song JY, Hulsman D, Serresi M, Tanger E, Blom M, Vens C, van Lohuizen M, Jacobs H, Citterio E. Tight regulation of ubiquitin-mediated DNA damage response by USP3 preserves the functional integrity of hematopoietic stem cells., 2014, 211(9): 1759–1777.

[80] Hu M, Li P, Li M, Li W, Yao T, Wu JW, Gu W, Cohen RE, Shi Y. Crystal structure of a UBP-family deubiquitinating enzyme in isolation and in complex with ubiquitin aldehyde., 2002, 111(7): 1041–1054.

[81] Joo HY, Zhai L, Yang C, Nie S, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Chang C, Wang H. Regulation of cell cycle progression and gene expression by H2A deubiquitination., 2007, 449(7165): 1068–1072.

[82] Sahtoe DD, van Dijk WJ, Ekkebus R, Ovaa H, Sixma TK. BAP1/ASXL1 recruitment and activation for H2A deubiquitination., 2016, 7: 10292.

[83] Jullien J, Vodnala M, Pasque V, Oikawa M, Miyamoto K, Allen G, David SA, Brochard V, Wang S, Bradshaw C, Koseki H, Sartorelli V, Beaujean N, Gurdon J. Gene resistance to transcriptional reprogramming following nuclear transfer is directly mediated by multiple chromatin- repressive pathways., 2017, 65(5): 873–884.e8.

[84] Sharma N, Zhu Q, Wani G, He J, Wang QE, Wani AA. USP3 counteracts RNF168 via deubiquitinating H2A and γH2AX at lysine 13 and 15., 2014, 13(1): 106–114.

[85] Wang ZQ, Zhang HL, Liu J, Cheruiyot A, Lee JH, Ordog T, Lou ZK, You ZS, Zhang ZG. USP51 deubiquitylates H2AK13,15ub and regulates DNA damage response., 2016, 30(8): 946–959.

[86] Uckelmann M, Densham RM, Baas R, Winterwerp HHK, Fish A, Sixma TK, Morris JR. USP48 restrains resection by site-specific cleavage of the BRCA1 ubiquitin mark from H2A., 2018, 9: 229.

[87] Morgan MT, Haj-Yahya M, Ringel AE, Bandi P, Brik A, Wolberger C. Structural basis for histone H2B deubiquitination by the SAGA DUB module., 2016, 351(6274): 725–728.

[88] Ramachandran S, Haddad D, Li C, Le MX, Ling AK, So CC, Nepal RM, Gommerman JL, Yu K, Ketela T, Moffat J, Martin A. The SAGA deubiquitination module promotes DNA repair and class switch recombination through ATM and DNAPK-mediated γH2AX ormation., 2016, 15(7): 1554–1565.

Histone ubiquitylation and its roles in DNA damage response

Qingyi Zhang1, Yingzi Zhang2, Kai Shen1, Shuyu Zhang2, Jianping Cao2

Ubiquitylation is an essential type of protein post-translational modifications (PTMs) in eukaryotes, which mediates various biological processes by regulating the subcellular localization, activity, and stability of proteins. Histones, as the main protein ingredients of chromatin, are closely coupled with DNA activities such as replication, transcription and repair, and therefore are the hotspots of PTMs. After DNA damage, histone ubiquitylations are involved in DNA damage response (DDR) by regulating nucleosome structure, activating cell cycle checkpoints, remodeling the nucleosome, and the recruitment and assembly of repair factors. Meanwhile, histone ubiquitylations can also crosstalk with other types of PTMs to regulate DDR processes. In this review, we summarize how the site-specific histone ubiquitylation forms signal network and contributes to DDR, which may shed light on the further study of how histone codes formed by histone PTMs affect the entire DDR processes.

histone; ubiquitylation; DNA damage response (DDR); crosstalk

2018-07-10;

2018-09-04

国家级大学生创新创业训练计划(编号:201610285039Z,201610285045Z)资助[Supported by the National Students’ Platform for Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (Nos. 201610285039Z, 201610285045Z)]

张卿义,本科在读,专业方向:临床医学。E-mail: zhangqingyi@outlook.com

曹建平,教授,博士生导师,研究方向:放射生物学。E-mail: jpcao@suda.edu.cn

10.16288/j.yczz.18-112

2018/10/20 14:54:00

URI: http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.1913.R.20181020.1453.004.html

(责任编委: 朱卫国)