饮料饮用量与溃疡性结肠炎发病风险相关性的Meta分析

2018-03-20冯爵荣

高 倩,李 瑾,冯爵荣,王 帆,林 雪,向 莉,张 林

武汉大学中南医院消化内科 湖北省肠病医学临床研究中心 武汉大学第二临床学院,湖北 武汉 430071

溃疡性结肠炎(ulcerative colitis,UC)是一种胃肠道的慢性炎症,主要临床表现为血便、腹痛及胃肠外表现[1],在过去20年间[2],UC发病率持续升高,由于频繁的复发、药物疗效有限及面临手术风险等原因[3-4],大部分患者生活质量低下,且承担着高昂的医疗费用[5-7]。但现在病因仍未明确,越来越多的证据[8]表明,饮食习惯参与了UC 的发病过程, LI 等[9]的Meta分析结果显示,进食蔬菜、水果可以降低UC的发病风险(OR=0.71,95%CI:0.58~0.88;OR=0.69, 95%CI:0.49~0.96),高膳食纤维饮食也可降低UC的发病风险(OR=0.80,95%CI:0.64~1.00),尽管既往关于饮料与UC发病风险关系的流行病学研究结论不一致,也没有Meta分析评估它们之间的关系,但西化的生活方式可能与UC发病率升高相关,饮料作为西化生活重要的一部分,可能与UC的发病风险相关。因此,我们做了这篇Meta分析探索饮料与UC的发病风险之间的关系。

1 资料与方法

1.1检索策略在PubMed (Medline)、 Embase 和Cochrane Library数据库使用关键词:“beverage”、“tea”、“alcohol”、“wine”、“beer”、“liquor”、“coffee”、“soda”、“soft drinks”、“diet”、“environmental factor”, “risk factor” 结合“inflammatory bowel disease”、“ulcerative colitis”、“IBD” 和“UC”,检索截至2016年10月1日的相关研究,我们也浏览了相关研究的参考文献中的研究、综述及未被检索到的Meta分析。

1.2纳入及排除标准所有研究均由2位调查人员独立审阅,纳入标准:已经见刊的观察性研究,包括至少一种饮料(茶、酒、咖啡、软饮料)的饮用量信息;评估这些饮料饮用量与UC发病率的关系;给出相对危险度(RR)或比值比(OR)和95%CI;排除无法获得全文的文章。

1.3数据提取和质量评估我们从纳入的研究中提取作者、发表日期、研究地点、试验类型、试验组及对照组病例数、调查方式、饮料类型、效应量(大量饮用组和少量饮用组间的RR或OR)及95%CI、协变量。

我们选用Newcastle-Ottawa Scale(NOS)[10]来评价纳入研究的质量,该方法包含9个项目,每个项目记1分。

1.4统计学分析由于UC 的发病率很低,在此Meta分析中,OR近似于RR[11],计算大量饮用组和少量饮用组间的RR值作为效应量,用Q检验和I2评价研究间的异质性[12],当异质性可以忽略时(I2<50%),选用固定效应模型[13],反之选用随机效应模型[14],在SAMUELSSON等[15]的研究中,啤酒、红酒和蒸馏酒的OR值是分开统计的,最后为了进一步研究将其综合起来。Meta回归分析用于在各个协变量中探索异质性的来源,使用亚组分析分别探究亚洲人种、高加索人种饮料饮用量与UC发病风险之间的关系,敏感性分析通过依次剔除各个研究来反映个体数据对综合结果的影响,同时Egger’s检验用于分析报告偏倚[16]。采用Stata SE12.0软件进行分析,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果

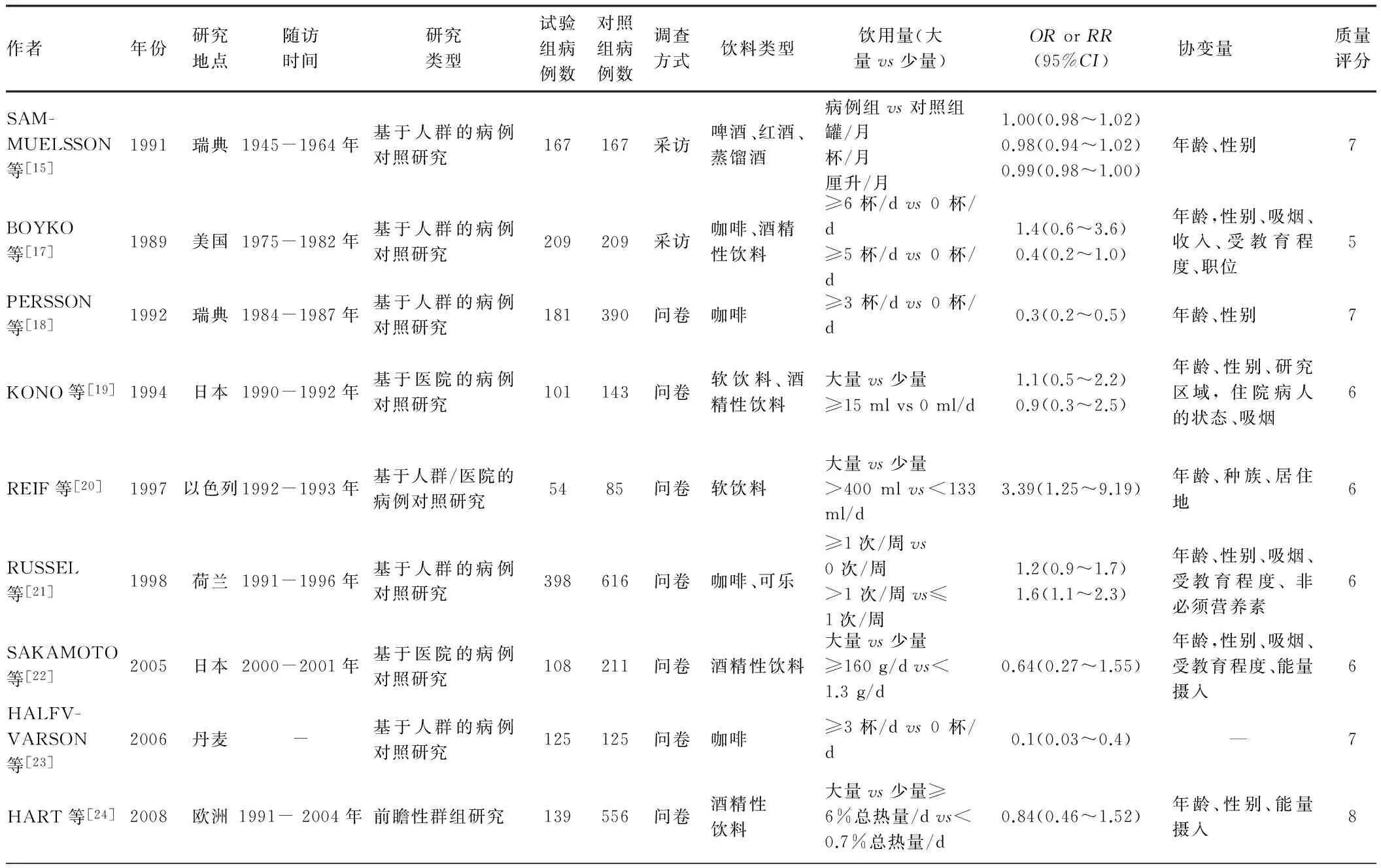

2.1检索结果和研究特征按照检索策略共检索到12 156篇文献,根据纳入、排除标准剔除重复发表文章6 063篇,阅读摘要后剔除6 070篇,筛选全文23篇,最终纳入13篇文献(其中3篇结果与本文关注点不相等,3篇未做文献质量评估,2篇缺乏健康对照组,1篇入选IBD患者,1篇为综述)。在13项研究中,只有1项是队列研究,剩余的12项均为病例对照研究。在12项病例对照研究中,8项来源于人群,3项来源于医院,1项来源于人群和医院,共有3 246例UC患者和5 494例病例对照。13项研究的基本特点如表1所示,研究质量评分5~8分,平均6.54分。

表1 纳入研究的基本特点Tab 1 The characteristics of included studies

续表1

作者年份研究地点随访时间研究类型试验组病例数对照组病例数调查方式饮料类型饮用量(大量vs少量)ORorRR(95%CI)协变量 质量评分HANSEN等[25]2011丹麦2003-2004年基于医院的病例对照研究144267问卷咖啡≥3杯/dvs<3杯/d0.89(0.52~1.53)年龄、性别6JAKOBSEN等[26]2013丹麦2007-2009年基于人群的病例对照研究56477问卷软饮料≥4次/周vs≤3次/周3.3(1.0~10.1) —7WANG等[27]2013中国2007-2010年基于人群的病例对照研究13081308问卷酒精性饮料、茶3-6次/周vs0次/周1.453(1.122~1.882)0.738(0.591~0.922)年龄、性别7NG等[28]2015亚澳地区2011-2013年基于人群的病例对照研究256940问卷软饮料、咖啡、茶≥2次/周vs<2次/周1次/dvs0次/d≥2次/周vs<2次/周亚洲1.432(0.742~2.762)0.508(0.361~0.716)0.632(0.464~0.862)亚洲和澳洲1.553(0.831~2.899)0.490(0.350~0.686)0.630(0.465~0.853)年龄、性别、城市、收入7

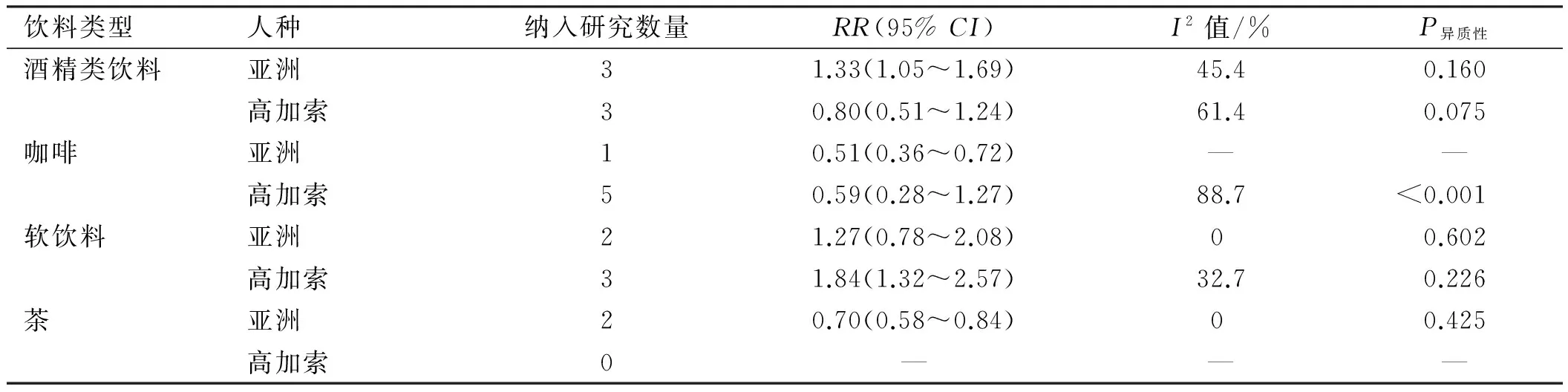

2.2酒精性饮料6项研究观察饮酒量和UC发病风险之间的关系,大量饮酒组与少量饮酒组间总RR为0.95(95%CI: 0.72~1.26,I2=65.7%,P异质性=0.012),显示二者之间无明显相关,考虑到研究间的高异质性,使用Meta回归分析研究异质性与发表日期、研究地点、病例数、研究类型、调查方式、吸烟、质量评分之间的关系,均未见明显相关。使用敏感性分析剔除单项研究后重新计算RR值较前无明显变化,范围从0.83(95%CI:0.61~1.12)到 1.05(95%CI: 0.82~1.35)。Egger检验未发现报告偏倚(P=0.810)。将研究分为亚洲人种、高加索人种两个亚组,发现亚洲人种中,大量饮酒较少量饮酒增加UC发病风险 (RR=1.33,95%CI:1.05~1.69),但在高加索人种中未见明显相关(RR=0.80,95%CI:0.51~1.24)(见图1、表2)。

图1 关于酒精性饮料饮用量和UC发病风险相关性的森林图Fig 1 Forest plot of alcohol consumption and the risk of UC for high vs low intake

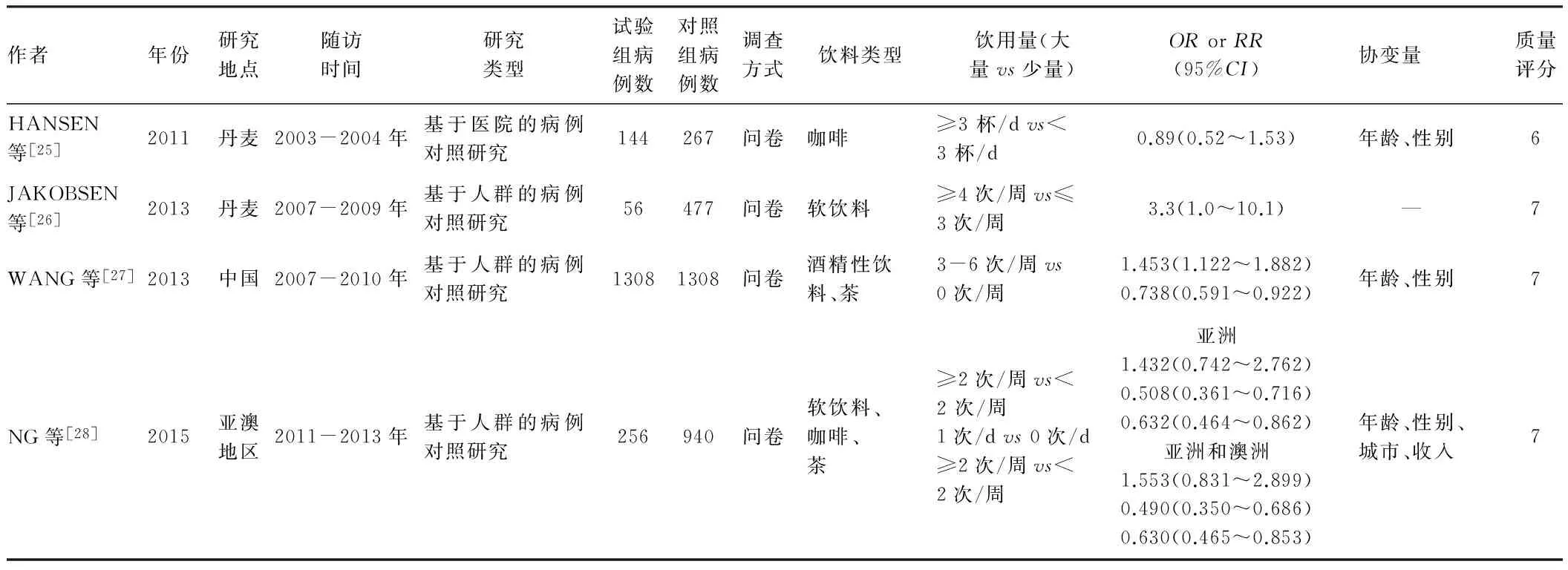

2.3咖啡6项研究评估咖啡饮用量与UC发病风险间的联系,大量饮用组与少量饮用组间的总RR值为0.58(95%CI:0.33~1.05,I2=87.5%,P异质性<0.001),说明大量饮用咖啡可能降低UC发病风险(见图2)。考虑到两研究间的高异质性,使用Meta回归及敏感性分析,在Meta回归分析中,没发现与异质性相关的因素,在敏感性分析中,两项研究(BOYKO等和 RUSSEL等)发现有助于异质性的形成。在进一步排除了这两项研究后,高异质性仍存在,总RR值为0.41(95%CI:0.22~0.74)。 Egger并没有反映出明显的报告偏倚(P=0.566)。

图2 关于咖啡饮用量和UC发病风险相关性的森林图Fig 2 Forest plot of coffee consumption and the risk of UC for high vs low intake

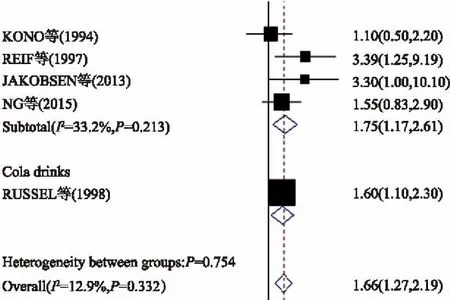

2.4软饮料5项研究报道了软饮料饮用量和UC发病风险间的联系。将关于可乐的研究纳入后,大量饮用组较少量饮用组的总RR值为1.66(95%CI:1.27~2.19,I2=12.9%,P异质性=0.332) , 剔除该研究后的总RR值为1.75(95%CI:1.17~2.61,I2=33.2%,P异质性=0.213),说明大量饮用软饮料可增加UC发病风险(见图3)。在亚组分析中,高加索人群软饮料饮用量与UC发病风险有关(RR=1.84,95%CI:1.32~2.57),但亚洲人群中未见明显相关 (RR=1.27,95%CI:0.78~2.08)(见表2)。

图3 关于软饮料饮用量与UC发病风险相关性的森林图Fig 3 Forest plot of the consumption of soft drinks and the risk of UC for high vs low intake

2.5茶2项研究评估了发生UC风险与茶饮用量之间的关系。2项研究对象均为亚洲人群,大量饮用和少量饮用组间的总RR值为0.70(95%CI:0.58~0.84,I2=0,P异质性=0.425),说明大量饮茶可降低UC发病风险(见表2)。

表2 亚洲人种及高加索人种中饮料饮用量与UC发病风险之间的相关性Tab 2 Beverage consumption and the risk of UC in Asian and Caucasian cohorts

3 讨论

本研究评价了最常见的4种饮料类型(酒精性饮料、咖啡、软饮料和茶)。就酒精性饮料而言,其饮用量与UC的发病风险并无明显相关,但在亚洲人群中明显相关。这可能与不同人种UC的发病机制不同有关,如 TLR4基因多态性:TLR4 Asp299Gly与高加索人种UC易感性相关,但在亚洲人群中无此相关性[29]。第二,西化的生活方式在亚洲人群中提高了饮酒量,但仍低于高加索人种。同时,亚洲人的UC发病率低于高加索人种,但近10年却在稳步上升。这也似乎提示饮酒量与UC发病率升高相关。SWANSON等[30]关于缓解期IBD患者饮用适量红酒的安全性评估的研究发现,在坚持每天饮用2杯红酒1周后,缓解期IBD患者粪便中钙调蛋白量较前降低,而尿蔗糖素分泌(大肠渗透性的标志物)上升,说明长期饮用红酒可能诱导缓解期IBD患者复发。总的来说,我们认为酒精性饮料是UC发病的潜在危险因素。

饮用咖啡可能一定程度上降低UC的发病风险,咖啡对于器质性疾病的作用一直备受争议。在 ZHANG等[31]和 ZHOU等[32]的Meta分析中,饮用咖啡可以降低口腔癌和子宫内膜癌的发病率。但是,饮用咖啡与胃癌发病风险无明显相关[33-34]。在 LANGHORST等[35]的临床随机对照试验中,草药、洋甘菊和咖啡炭在维持UC缓解上与美沙拉嗪显示出相似的疗效和安全性。但由于研究间的高异质性(I2=87.5%),为了进一步了解二者间的联系需要纳入大型的前瞻性研究。

关于软饮料,其饮用量与UC的发病相关,特别是在高加索人群中。软饮料导致肥胖和相关的慢性疾病[36-38],一直是热门的公共健康问题。其次,我们认为大量的食品添加剂也可以伤害肠道黏膜,长期大量的饮用软饮料可能导致慢性的黏膜损伤。最后,软饮料提高了糖的摄入,而在WANG等[39]的研究中发现,UC的发病与高糖相关。我们认为,软饮料可能增加UC的发病风险。

茶的饮用量与UC的发病率呈负相关。2项研究对象均为亚洲人群且均为负相关。我们认为亚洲人种较高加索人种较低的UC发病率可能一部分归功于大量饮茶。两项动物实验[40-41]发现,结合茶叶萃取物和柳氮磺嘧啶较单独使用柳氮磺嘧啶更能有效地控制大鼠的肠道炎症,绿茶和咖啡富含多酚类物质,有抗氧化作用,同时可通过减少NF-κB抑制巨噬细胞产生TNF-α[42-43]。我们的研究认为,饮茶是UC发展中潜在的保护因子。

这个Meta分析有几项优点。首先,这是研究UC发病风险与饮用量之间的Meta分析。第二,文章纳入的研究规模相对较大,减少抽样误差。第三,在酒精性饮料和咖啡的分析中并没有发现报告误差。但研究也有局限性,首先纳入的研究均为病例对照研究,容易产生相当大的偏差,特别是回忆偏倚和调查员偏倚。其次,纳入的研究数量较少,且研究间异质性较大可能导致研究结果不准确。最后,不是每个研究中所有的混杂因素都被校正。

总的来说,该Meta分析显示,大量饮用软饮料可能提高UC的发病率,但大量饮茶可能降低这种风险。

[1] NG S C, TANG W, CHING J Y, et al. Incidence and phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease based on results from the Asian-pacific Crohn’s and colitis epidemiology study [J]. Gastroenterology, 2013, 145(1): 158-165. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.007.

[2] MOLODECKY N A, SOON I S, RABI D M, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review [J]. Gastroenterology, 2012, 142(1): 46-54, e42. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001.

[3] LI J, WANG F, ZHANG H J, et al. Corticosteroid therapy in ulcerative colitis: clinical response and predictors [J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2015, 21(10): 3005-3012. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i10.3005.

[4] WANG F, LIN X, ZHAO Q, et al. Adverse symptoms with anti-TNF-alpha therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and duration-response meta-analysis [J]. Eur J Clin Pharmacol, 2015, 71(8): 911-999. DOI: 10.1007/s00228-015-1877-0.

[5] HUOPONEN S, BLOM M. A systematic review of the cost-effectiveness of biologics for the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases [J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(12): e0145087. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145087.

[6] VAN DER VALK M E, MANGEN M J, SEVERS M, et al. Comparison of costs and quality of life in ulcerative colitis patients with an ileal pouch-anal anastomosis, ileostomy and anti-TNFα therapy [J]. J Crohns Colitis, 2015, 9(11): 1016-1023. DOI: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv117.

[7] NIEWIADOMSKI O, STUDD C, HAIR C, et al. Health care cost analysis in a population-based inception cohort of inflammatory bowel disease patients in the first year of diagnosis [J]. J Crohns Colitis, 2015, 9(11): 988-996. DOI: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv117.

[8] SPOOREN C E, PIERIK M J, ZEEGERS M P, et al. Review article: the association of diet with onset and relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease [J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2013, 38(10): 1172-1187. DOI: 10.1111/apt.12501.

[9] LI F, LIU X Q, WANG W J, et al. Consumption of vegetables and fruit and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis [J]. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2015, 27(6): 623-630. DOI: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000330.

[10] WELLS G, SHEA B, O’CONNELL D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses [C/OL]. 2011. Available: http://www.ohri.ca.

[11] ZHANG J, YU K F. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes [J]. JAMA, 1998, 280(19): 1690-1691.

[12] HIGGINS J P, THOMPSON S G, DEEKS J J, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analysis [J]. BMJ, 2003, 327(7414): 557-560. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557.

[13] MANTEL N, HAENSZEL W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease [J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 1959, 22(4): 719-748.

[14] DERSIMONIAN R, LAIRD N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials [J]. Control Clin Trials, 1986, 7(3): 177-188.

[15] SAMUELSSON S M, EKBOM A, ZACK M, et al. Risk factors for extensive ulcerative colitis and ulcerative proctitis: a population based case-control study [J]. Gut, 1991, 32(12): 1526-1530.

[16] EGGER M, DAVEY SMITH G, SCHNEIDER M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test [J]. BMJ, 1997, 315(7109): 629-634.

[17] BOYKO E J, PERERA D R, KOEPSELLT D, et al. Coffee and alcohol use and the risk of ulcerative colitis [J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 1989, 84(5): 530-534.

[18] PERSSON P G, AHLBOM A, HELLERS G. Diet and inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study [J]. Epidemiology, 1992, 3(1): 47-52.

[19] Dietary and other risk factors of ulcerative colitis. A case-control study in Japan. Epidemiology Group of the Research Committee of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Japan [J]. J Clin Gastroenterol, 1994, 19(2): 166-171.

[20] REIF S, KLEIN I, LUBIN F, et al. Pre-illness dietary factors in inflammatory bowel disease [J]. Gut, 1997, 40(6): 754-760.

[21] RUSSEL M G, ENGELS L G, MURIS J W, et al. ‘Modern life’ in the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study with special emphasis on nutritional factors [J]. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 1998, 10(3): 243-249.

[22] SAKAMOTO N, KONO S, WAKAI K, et al. Dietary risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease-a multicenter case-control study in Japan [J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2005, 11(2): 154-163.

[23] HALFVARSON J, JESS T, MAGNUSON A, et al. Environmental factors in inflammatory bowel disease: a co-twin control study of a Swedish-Danish twin population [J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2006, 12(10): 925-933. DOI: 10.1097/01.mib.0000228998.29466.ac.

[24] HART A R, LUBEN R, OLSEN A, et al. Diet in the aetiology of ulcerative colitis: a European prospective cohort study [J]. Digestion, 2008, 77(1): 57-64. DOI: 10.1159/000121412.

[25] HANSEN T S, JESS T, VIND I, et al. Environmental factors in inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study based on a Danish inception cohort [J]. J Crohns Colitis, 2011, 5(6): 577-584. DOI: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.05.010.

[26] JAKOBSEN C, PAERREGAARD A, MUNKHOLM P, et al. Environmental factors and risk of developing paediatric inflammatory bowel disease-a population based study 2007-2009 [J]. J Crohns Colitis, 2013, 7(1): 79-88. DOI: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.05.024.

[27] WANG Y F, OU-YANG Q, XIA B, et al. Multicenter case-control study of the risk factors for ulcerative colitis in China [J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2013, 19(11): 1827-1833. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i11.1827.

[28] NG S C, TANG W, LEONG R W, et al. Environmental risk factors in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based case-control study in Asia-Pacific [J]. Gut, 2015, 64(7): 1063-1071.DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307410.

[29] CHENG Y, ZHU Y, HUANG X, et al. Association between TLR2 and TLR4 gene polymorphisms and the susceptibility to inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis [J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(5): e0126803. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126803.

[30] SWANSON G R, TIEU V, SHAIKH M, et al. Is moderate red wine consumption safe in inactive inflammatory bowel disease? [J]. Digestion, 2011, 84(3): 238-244. DOI: 10.1159/000329403.

[31] ZHANG Y, WANG X, CUI D. Association between coffee consumption and the risk of oral cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies [J]. Int J Clin Exp Med, 2015, 8(7): 11657-1165.

[32] ZHOU Q, LUO M L, LI H, et al. Coffee consumption and risk of endometrial cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies [J]. Sci Rep, 2015, 5: 13410. DOI: 10.1038/srep13410.

[33] LI L, GAN Y, WU C, et al. Coffee consumption and the risk of gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies [J]. BMC Cancer, 2015, 15: 733. DOI: 10.1186/s12885-015-1758-z.

[34] ZENG S B, WENG H, ZHOU M, et al. Long-term coffee consumption and risk of gastric cancer: a PRISMA-compliant dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies [J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2015, 94(38): e1640. DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001640.

[35] LANGHORST J, VARNHAGEN I, SCHNEIDER S B, et al. Randomised clinical trial: a herbal preparation of myrrh, chamomile and coffee charcoal compared with mesalazine in maintaining remission in ulcerative colitis-a double-blind, double-dummy study [J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2013, 38(5): 490-500. DOI: 10.1111/apt.12397.

[36] CHEUNGPASITPORN W, THONGPRAYOON C, EDMONDS P J, et al. Sugar and artificially sweetened soda consumption linked to hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis [J]. Clin Exp Hypertens, 2015, 37(7): 587-593.DOI: 10.3109/10641963.2015.1026044.

[37] HEUNGPASITPORN W, THONGPRAYOON C, O’CORRAGAIN O A, et al. Associations of sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened soda with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis [J]. Nephrology (Carlton), 2014, 19(12): 791-797. DOI: org/10.1111/nep.12343.

[38] GREENWOOD D C, THREAPLETON D E, EVANS C E, et al. Association between sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened soft drinks and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies [J]. Br J Nutr, 2014, 112(5): 725-734. DOI: 10.1111/nep.12343.

[39] WANG Y F, OU-YANG Q, XIA B, et al. Multicenter case-control study of the risk factors for ulcerative colitis in China [J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2013, 19(11): 1827-1833. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i11.1827.

[40] TANG J, ZHENG J S, FANG L, et al. Tea consumption and mortality of all cancers, CVD and all causes: a meta-analysis of eighteen prospective cohort studies [J]. Br J Nutr, 2015, 114(5): 673-683. DOI: 10.1017/S0007114515002329.

[41] BYRAV D S, MEDHI B, VAIPHEI K, et al. Comparative evaluation of different doses of green tea extract alone and in combination with sulfasalazine in experimentally induced inflammatory bowel disease in rats [J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2011, 56(5): 1369-1378. DOI: 10.1007/s10620-010-1446-4.

[42] KOO M W, CHO C H. Pharmacological effects of green tea on the gastrointestinal system [J]. Eur J Pharmacol, 2004, 500(1-3): 177-185. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.07.023.

[43] PODIO N S, L0PEZOPRZ-FROILAN R, RAMIREZ-MORENO E, et al. Matching in vitro bioaccessibility of polyphenols and antioxidant capacity of soluble coffee by boosted regression tress [J]. J Agric Food Chem, 2015, 63(43): 9572-9582. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b04406.