建筑的灵魂

——溢于言表

2018-03-052017年9月7日

2017年9月7日

国际建筑师协会金奖得主首尔讲座伊东丰雄

何谓“建筑的灵魂”?对我而言,这与“何谓建筑”如出一辙。只需解答“何谓建筑”,便可弄清何谓“建筑的灵魂”。

2011年3月11日,日本东北部发生里氏9.0级大地震。地震引发海啸肆虐,导致逾2万人丧生。海啸过后,家园不复存在,只剩一片狼藉。灾难发生后,我曾前往多个受灾区,亲眼目睹在灾难中流离失所的人群。多数居民只能在小学操场临时避难,他们中的大多数是年迈的长者和女性,以种植或捕鱼为生,他们的日常生活与居住在大城市的现代人的生活方式截然不同。海啸过后,受灾居民只能暂住于临时住房内,别无他选。当我到达受灾区时,我发现受灾居民的临时住房空间十分狭小,只有小型集装箱一般大。这些临时避难所依循现代建筑理论而建,并不适合农民和渔民的生活方式。虽然临时住房的主要目的是为每户家庭提供私密空间,但这却导致形成一个个孤立封闭的单元。因此,居住在这些小型、封闭的箱式住房内的居民大多深感孤独。在亲眼目睹灾后狼藉景象和临时住房亟待改善的居住环境后,我扪心自问:“作为一名建筑师,我能做些什么?”

于是,我决定筹集善款,修建“共有之家”。“共有之家”是供临时住房内的居民居住的小型公屋。每间大小仅40平方米,主体为开放式木质结构,设有缘侧、土间、大桌、燃木火炉和榻榻米,与当地居民在灾前习惯居住的农舍相似。受灾居民在看到“共有之家”后,心情激动,喜极而泣。对我本人而言,“共有之家”并非一件“艺术品”,而是一幢“建筑”。

如今,受海啸影响城镇的灾后重建工作正在稳步推进,但大部分重建工作仍在现代建筑理论指导下展开。每一块区域依照同一个设计方案。当地政府开挖、平整山区土地,修建新住宅,并使用开挖的土壤填海造陆,修建高大的防波堤。如果防波堤高度超过10米,则底部基础的宽度介于60至80米。这些巨型防波堤与金字塔有着相同的剖面。防波堤切断了海洋与生活区之间的联系。渔民根本无法看见海洋。现代建筑理论宣称人类可以通过技术统治自然,但生活在海啸侵袭地区的人们承认他们无法战胜自然。相反,他们敬畏自然,同时对自然的恩赐怀有感激之心。

相比之下,东京的传统住宅区每年正迅速兴建高层公寓和写字楼。建筑越高,离自然越远,建筑越多,同质化越严重。在我的印象中,东京是一座街道布局同质化的城市。在不久的将来,随着东京市民和居住空间愈发脱离自然,他们彼此之间将越来越难以区分。

文化人类学家中泽新一《建筑的伦理》一文给我留下深刻的印象。文中提到,西藏人民在修建寺庙前,会事先禀告“土地神”,征求其同意。这是因为即便是西藏人民,在兴建建筑时也会运用几何学原理。但是,大自然本身如同旋涡一般始终在转动,而人类修建的几何建筑会破坏自然的流动性,两者之间存在尖锐的矛盾。

从外观看,寺庙的几何设计给游客留下理性印象,走进寺内,几何图形的痕迹减弱,大自然的活力再度复苏。寺庙内部通过利用烛火散发的香味、五彩缤纷的纺织品形成的视觉冲击、引人注目的神秘灯光等元素影响游客的感官,将游客重新带回自然。我对书中提到将笛卡尔网格转变为大自然动态流动空间的概念十分感兴趣,希望能够在设计项目中进行深入探索。

对于台湾大学社会科学院项目而言,我希望设计一个舒适的空间,让人感觉坐在树下阅读,阵阵微风迎面吹拂。为实现这一设想,我在屋顶采用莲花状放射几何图形。通过将莲花状图形连接,从而确定柱状物的中心点。其次,通过运用泰森多边形确定屋顶的最终形状。从整体上看,屋顶犹如一片片荷叶。通过借助上述算法,树下阅读的景象跃然眼前。

最近,我还参与了药师寺斋堂(Jikido)的修复项目。药师寺是奈良境内的一座名寺,建于1300年前。该寺庙由五幢主要建筑组成,除东塔外的所有建筑均已于近期重建。Jikido原为僧人用膳的斋堂。设计方要求斋堂外观必须按原有样式重建,而斋堂内部可自由设计。重建后的斋堂将用作艺术馆和活动举办场地。我正好负责斋堂内部的设计工作。斋堂正中悬挂着一幅由日本画家绘制的巨型阿弥陀如来画像,画像两侧同为该名画家绘制的14幅风景画。这些画像描绘阿弥陀如来从西安古都东渡日本奈良之行。日本旧都奈良城虽采用笛卡尔网格布局,但规整设计下仍留有自然景观之空间。斋堂天花板被设计为阿弥陀如来头顶光环的延展部分。光环由铝板制成,悬挂于天花板下方。铝板经镭射切割,并镀成金色。天花板图案为连续的同心圆波纹。

旧时,东方的卷草纹常被用作风吕敷的图案。古老的“唐狮子”图案就由这些复杂的漩涡纹样组成。日本平面设计大师杉浦康平曾写过一篇有关这类图案的美文:

“旋涡纹样的力量通过卷草纹设计传递予风吕敷包裹的物件。物件的内部力量慢慢苏醒,物件开始有了心跳。风吕敷的旋涡纹样不仅仅起到装饰作用。对于亚洲人而言,旋涡纹样是一种神圣的图式,可将物件的内力与人心相连通。旋涡纹样随处可见,它就像催化剂催化出物件的内部力量。“大家的森林:岐阜媒体中心”是我接下来要说的项目。该项目是一幢图书馆综合建筑,内设美术馆、小礼堂和公共交流空间。该建筑位于日本中部山地地区,四周林木繁茂。建筑高2层,每层楼面积为90m x 80m。第二层是连续的流动空间,未设分隔墙。阅读区的“globe”形似大伞,由聚碳酸酯的纺织物制成。

该部分介绍建筑的主要设计概念。“globe”结构从顶部收集空气和自然光,同时起到柔光作用。由于项目场地临近主要河流,我们希望将这一地下水源引入建筑内部,发挥地下水水温全年稳定的优势。地下水流经第一、二层的混凝土楼板,起到为建筑供暖或冷却的作用。地下水通过辐射楼面系统在建筑内部循环,营造出舒适的室内环境。除辐射供暖和冷却系统外,视季节不同,整个图书馆内形成冷/暖空气循环。夏季,暖空气升腾,并从“globe”结构顶部排出。冬季,“globe”结构顶部的开口关闭,暖空气仅在“globe”结构内部循环。在岐阜媒体中心,我们通过尽可能多地利用自然能源,成功将该建筑的能耗降至传统建筑的一半。

除能源系统外,屋顶采用由本地桧木(日本扁柏)制成的木质结构。该结构系统十分特殊。每根木条厚度仅2厘米,弯曲性能优良。通过将木材组件以60°角铺设,形成起伏状屋顶。波浪起伏的屋顶增强了屋顶结构的稳定性,并充当外壳结构件。同时,有助于促进空气流通,并与周围环境和谐融为一体。在图书馆的第二层,我们可闻到桧木的芳香。“globe”结构下方是最适合阅读的区域。“globe”结构悬挂于第二层天花板下方,共分四个规格(直径介于8至14米)。书架呈螺旋状摆放于各“globe”结构的正下方,形成流动性空间。读者可自由徜徉其中,自行选择11个不同的阅读区。

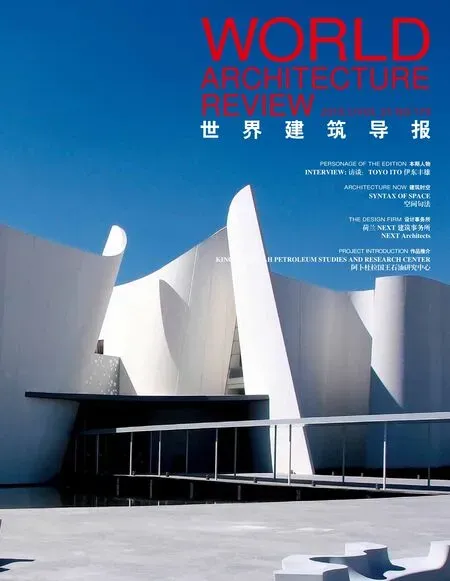

最后,我想提一提台湾的台中歌剧院。台中歌剧院是一幢综合性建筑,由大中小三座剧场组成:大剧院2,000席、中剧院800席、小剧场200席。小剧场设有开放式后台,可与户外剧场相连。矩形外观与三维曲面设计形成强烈反差。如同台大图书馆项目,该项目同样以网格几何图形为基础,但又不止于此。网格图形变换为连续的三维曲面。该建筑的结构模型十分复杂。该部分揭示空间如何流动以及如何像液体一般连续。该项目从最初竞标阶段起,共耗时11年,于去年秋(9月30日)正式开馆。歌剧院开放后,每天活动不断,人流如织,令我倍感欣慰。

所有这些项目都代表我对“建筑的灵魂”的认识,其本质源于对自然的认同。这种情感与海啸侵袭地区的农民和渔民怀有的情感相同。即使在当代社会,我们也不应当忘记——人是自然界的一部分,建筑也是自然界的一部分。

What is the “soul of architecture”? This is the same question as “what is architecture” for me. We can discover the “soul of architecture” by pursuing the answer to the question of“what is architecture”.

On March 11th, 2011, a large magnitude-9 earthquake hit the north-eastern part of Japan. The unleashed tsunami took more than 20,000 lives. After the tsunami, nothing but rubble was leftover. In the aftermath of the disaster, I visited many places and saw the people who had lost their homes and towns. Most of the residents had taken refuge in the gymnasiums at primary schools. Many of them were old men and women who had been working as farmers or fi shermen, their daily lives were quite a contrast compared to the lifestyles of the modern people living in big cities. The residents struck by the disaster had no choice but to move to temporary housing in the aftermath of the tsunami. When I visited, I noticed that the space of their temporary housing was so tiny, like a small container box. These temporary shelters were made based on a modernist philosophy and were ill-suited for the lifestyles of the farmers and fisherman. The primary objective of this temporary housing was to create and assure privacy for each family, but this resulted in creating separate, closed units that were very isolating. As a result, many people were very lonely living in these small, secluded boxes. Seeing all the destruction and the inadequate state of their temporary housing, I asked myself, “what can I do as an architect?”.

So, I decided to ask for donations to build “Minna no Ie (Home-for-All)”, a small communal house for the residents living in temporary housing. While only 40m2 in size, the communal house contained an engawa, a doma, a big table, a wood burning stove, and a tatami space. It is made from a wooden structure and opens to nature, similar to the farm houses that the local people had been accustomed to living in before the tsunami. When the residents saw this “Home-for-All”, they were so pleased and they cried tears of joy.For me, this creation is not “artwork” but “architecture”.

Today, reconstruction in the towns damaged by the Tsunami is moving forward. But much of the reconstruction is still based on a modernist architectural ideology. Every area follows almost the same plan. They cut and fl atten the land in the mountainous area for new housing, fi ll in the seaside areas with this soil, and construct high seawalls. If the height of the seawall is 10m, the width of the base is 60–80m wide. These massive seawalls have the same section as the pyramids. The connection between the sea and the living area is sharply bisected by these walls. The fi shermen cannot see the sea at all. Modernist architectural ideology states that people can dominate nature through technology. But the people who lived in these tsunami stricken areas acknowledge that they can never overcome nature. Instead, they fear nature, they respect nature and they show gratitude for the blessings of nature.

In contrast, traditional housing areas in Tokyo are developed into high-rise apartments or office buildings rapidly every year. The taller the buildings, the more they are divided from nature and blend all together as indistinguishable towers within the urban metropolis. My image of Tokyo is that of a city covered in homogeneous grids. In the near future, I fear the people and living spaces of Tokyo will become almost unrecognizable from one another as all becomes more and more disconnected from nature.

I am impressed by the essay “The Ethics of Architecture” by Shinichi Nakazawa (a cultural anthropologist). He says when the people in Tibet build temples, they ask the “God of the Earth” to allow the construction. This is because even the people in Tibet must utilize geometry when they build architecture. But in contrast, nature itself is always fl uid like swirls. The resulting man-made geometry con fl icts against this natural fl uidity. This creates a sharp contradiction.

The exterior view of the temple gives viewers a rational impression due to the traces of geometry. But when people enter inside, this geometry fades out, and the dynamism of nature is revived again. The interior space of the temple brings the visitors back to nature by appealing to their fi ve senses: the scent of the numerous candles burning, the vision of the richly colored textiles, the dramatic mysterious light, and so on. I am very interested in this transformation of the Cartesian grid into the dynamic fl uid space of nature and wanted to explore this concept in a number of my projects.

At the National Taiwan University, College of Social Sciences, I wanted to create a comfortable space based on the idea of man reading under a tree, feeling a gentle breeze. To realize this vision, I introduced a radial geometry like a pattern of lotus fl owers. When connecting these patterns, the center points of the columns are determined. Then, by using a Voronoi pattern, the fi nal shape of the roof was determined. Altogether, it looks like the leaves of a lotus flower. By using these algorithms, the image of reading under the trees was realized.Recently I also participated in the restoration project of Jikido of Yakushi-ji, one of the most popular temples in Nara, built 1300 years ago. This temple is made up of five main buildings, all the buildings except Toto (East tower) were rebuilt recently. Jikido was originally a dining space for monks. The outside had to be reconstructed in the original style, but the inside could be designed almost freely, and was to be used as gallery and event space. I was tasked with designing the interior space. At the center of the space, a large painting of Amidah (Amida Nyorai) by a Japanese painter is hung with 14 landscape paintings by the same painter exhibited on either side. These paintings illustrate the travels of the monk from Seian, the capital of China in old days, to Nara, Japan. Nara, the old capital of Japan, was created based on a Cartesian grid and yet the natural landscape is allowed to intrude inside this grid space. The ceiling design is intended to be an extension of Amidah’s halo. It is made of aluminum panels hung from the ceiling. The panels were laser cut and dyed a golden hue. The pattern of the ceiling is that of continuous waves of concentric circles.

In the old days, the oriental arabesque was very popular as the pattern of furoshiki. The ancient paintings of the lion called Karajishi is made up of these complex swirls. In speaking about these patterns, Kohei Sugiura,a famous graphic designer in Japan, wrote the beautiful essay.

“The power of the swirl transfers to the item wrapped by Furoshiki with the arabesque design. The internal force of the item awakens, and the item begins to have a heart. The swirls of Furoshiki act beyond the role of mere decoration. For Asian people, the swirl symbolizes a holy image that connects the heart of an item to human beings. The swirl is a catalyst to incite the internal force of items, and this pattern can be found everywhere.”

The next project I want to mention is ‘Minna no Mori’ Gifu Media Cosmos. This project is a library complex which contains an art gallery, small auditorium and communication space for the local people. It is located in the mountainous area of central Japan. The building has only 2 stories but each floor plate is 90m x 80m,surrounded by a lush landscape. The space on the and floor is fluid and continuous, without walls. The “globes”in the reading space look like large umbrellas, and are made from a combination of polycarbonate and a fabric textile.

This section shows the main concept of the building. The globes gather air and natural light from the top and gently fi lter in light. The site is close to a big river, so we wanted to use this underground water source within

the building since its temperature is stable throughout the year. Groundwater flows through the concrete slabs of the 1st and 2nd floor to either warm or cool the building. This radiant fl oor system circulates the groundwater to create a comfortable indoor climate. In addition to the radiant heating and cooling system, the warm or cool air also circulates in the entire space based on seasonality. In the summer, the warm air rises and eventually discharges from the top of the globes. In the winter, the warm air circulates in the globes simply by shutting the openings at the top. At Gifu, we have reduced the energy consumption to half of what conventional buildings use by utilizing natural energy as much as possible.

In addition to the energy system, the roof is a timber structure made from local hinoki (Japanese cypress). The structural system is very special. Each timber piece is only 2cm thick, which makes it very easy to bend. The roof is created by laying these timber members at 60-degree angles to create the undulating roof. By making the roof form wavy, the structure becomes stronger since it acts as a structural shell. The undulating roof form also promotes the circulation of air and harmoniously blends into the surrounding landscape. On the 2nd fl oor, we can smell the fragrant hinoki. The most suitable spaces for reading are beneath the globes. The globes are hung from the ceiling on the second fl oor and range in four sizes: from 8 to 14 meters in diameter. The bookshelves are all arranged in spirals beneath the center of each globe, creating very fl uid spaces underneath. People can wander freely and pick and choose from the eleven diあerent reading spaces.

Finally, I have to mention the Taichung Opera House in Taiwan. It is a complex that contains three theaters: Grand Theater with 2000 seats, Playhouse with 800 seats, Black Box with 200 seats. The backstage of the Black Box can be opened and connected to the outdoor amphitheater. The exterior view shows the contrast between the rectangular form and the threedimensional curve. Like the Taiwan University Library project, this project also starts from a grid geometry, but transforms it. The grid pattern is transformed into a continuous three-dimensional curve. The structural model of this building is very complex. This section reveals how the space is fl uid and continuous like liquid. This project took a total of 11 years to complete from the initial competition stage, opening last autumn on September 30th. After the opening, I am happy to see that the opera house bustles with the activity of people every day.

All these projects represent the “Soul of Architecture” for me, which at its core comes from a sympathy to nature. This sentiment about nature is the same that the farmers and fi shermen in the tsunami-stricken area held. Even in our contemporary society, we should not cease to forget that human beings are a part of nature, thus architecture is also a part of nature.