Prevalence of physical fitnes in Chinese school-aged children:Findings from the 2016 Physical Activity and Fitness in China—The Youth Study

2018-01-08ZhengZhuYangYangZhenxingKongYiminZhangJieZhuang

Zheng Zhu ,Yang Yang ,Zhenxing Kong ,Yimin Zhang ,*,Jie Zhuang ,*

a Shanghai Research Center for Physical Fitness and Health of Children and Adolescents,Shanghai University of Sport,Shanghai 200438,China

b School of Kinesiology,Shanghai University of Sport,Shanghai200438,China

c Shanghai Municipal Center for Students’Physical Fitness and Health Surveillance,Shanghai Municipal Education Committee,Shanghai200011,China

d Key Laboratory of Exercise and Physical Fitness,Ministry of Education,Beijing Sport University,Beijing 100084,China

1.Introduction

Physical fitness commonly consisting of cardiorespiratory endurance,muscle strength endurance,fl xibility,and body composition,is an important health marker1and is a critical part of the overall physical and mental health and grow th in school aged children.2Physical fitnes has been shown to be positively associated with cognition,2,3weight status,4psychological well-being,5academic achievement scores,2,6,7and performance of real-world tasks.8Low physical activity or fitness in contrast,can lead to the development of cardiovascular disease risks and an increased prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors in childhood,9which can,in turn,track into adulthood.1

The public health importance of physical fitnes in school aged children suggests the need to include systematic physical fitnes assessment in health monitoring and promotion for young populations.The importance of adopting this practice is even greater in China in light of the major social,demographic,and epidemiologic changes over the past 3 decades that have impacted the nutrition and behavioral lifestyles of many Chinese schoolchildren.Evidence from national fitnes assessments of school children indicates a clear trend of decline in various indicators of physical fitnes over a20-year period,with increased levels of body mass index(BM I).10A leveling-off of the early declining trend in fitnes was reported in 2010 and 2014,but an increase in BMI continued.11,12However,given the recent negative trends in low physical activity13-15and rates of obesity16,17among children and adolescents,the need for monitoring and tracking schoolchildren’s physical fitnes remains as a high public health priority.Filling this know ledge gap will also help support the development and implementation of childhood cardiovascular risk surveillance programs.

The2016Physical Activity and Fitness in China—The Youth Study(PAFCTYS)used the 2014 revised fitnes standards to carry out a comprehensive assessment conducted by trained examiners.By analyzing the data from the PAFCTYS,the purposes of this study were to present the most recent prevalence estimates of Chinese school-aged children meeting physical fitnes standards and to examine differences by sex and residence locale in children who did not meet the current fitnes standards.

2.Methods

2.1.Study design and participants

The PAFCTYS is a cross-sectional study involving surveys of physical activity and assessment of physical fitnes among Chinese school-aged children in 2016.The PAFCTYS applied a multistage stratifie cluster sampling method to recruit a total of 195,047 children in Grades1 through 12 from 1036 schools in 32 provinces,municipalities,and autonomous regions across the country.No power calculations were conducted on the sample size.Details of the study design and methodologies are described elsewhere.18The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shanghai University of Sport.Informed consent was obtained from the all participating children’s parents or guardians,and verbal agreement to participate was obtained from all the children prior to the survey.

From the total sample,we analyzed the data from 171,991 children(88%)from 3 school grade categories in the Chinese education system:primary schools(Grades1–6),junior middle schools(Grades7–9),and junior high schools(Grades10–12).These children participated in the grade-and sex-specifi physical fitnes assessment and provided complete anthropometric measurement data.A total of 23,056 children(12%,8608 in primary schools,3726 in junior middle schools,and 10,722 in junior high schools)were excluded from the original PAFCTYS data because some participants were unable to fully complete the physical fitnes test battery or because assessments for some participating schools were can celled on severe air pollution days.

2.2.Data collection

Measures of physical fitnes were collected by trained regional research staff and assistants(test examiners)who were recruited from 32 universities or colleges in China.These individuals completed an orientation and training course,conducted by the investigators,on fitnes assessment using the Chinese National Student Physical Fitness Standard(CNSPFS)battery.19Study outcome measurements were taken using standard protocols on school campuses during regular school hours.Prior to assessment,participating children were given detailed information and instructions on the fitnes assessment and were provided with ample time to ask questions about it.Data collection was conducted in all schools concurrently from October to November,2016.

2.3.Measures

Physical fitnes was assessed using the revised 2014 version of the CNSPFS,19which involves a total of 11 fitnes indicators described below.Following the guidelines,test examiners conducted each test per a protocol deter mined a priori.Each fitnes indicator score was weighted by a grade-and sex-specifi percentage(see Table S1 in the online supplement).

2.3.1.BM I

BMI was used as a surrogate of body composition.Children’s height was measured to the nearest0.1 cm in bare feet where as body weight was measured to the nearest0.1 kg.Both of these measures were assessed using a portable instrument(GMCS-IV;Jianmin,Beijing,China).From these values,BM I values were calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters(kg/m2).Anthropometric measures were obtained from the children in each of the 3 grade categories(i.e.,primary,junior middle,and junior high schools).

2.3.2.Vital capacity(VC)of lung

In a quiet assessment setting,children’s vital capacity(VC)was assessed via spirometry.VC is define as the maximum volume of air(measured in milliliters)a child can expel from his or her lungs after a maximum inhalation.The test was repeated 3 times on each child,and his or her best performance from the3 tests was recorded.The VC evaluation measure was obtained from the children of all3 school grade categories.

2.3.3.50m sprint

To assess speed in this test,children were instructed to run in a straight line on a fla and clear surface as fast as possible for a 50 m distance.This test was performed once(as a single maximum sprint)for each child,and the time for the run was recorded,at the finis line,to the nearest 0.1 s.This measure was assessed for all participating children.

2.3.4.Sit and reach

As a f exibility indicator,children were instructed to perform a sit and reach test.In a seated position with both knees fully extended and feet placed fi mly against a vertical support,children were asked to reach forward with their hands,along a measuring line,as far as possible.Two trials were given to each child,with the score recorded(measured to the nearest0.1 cm)on the farthest distance reached in the2 trials.This measure was assessed for all participating children.

2.3.5.Timed rope-skipping

As a measure of motor coordination,children were instructed to perform a rope-skipping task requiring that they take off and land on both feet.After determining appropriate size and length of rope for each child,the child was asked to jump continuously for 1m in,with the total number of jumps recorded.This measure was assessed only for primary school children(Grades1–6).

2.3.6.Timed sit-ups

As a measure of abdominal muscle strength,children were instructed to perform a1m in sit-up test.The protocol required that children lay in a supine position with the knees bent and feet fla on a floo mat(secured by the test examiner)with their hands placed on the back of the head and finger crossed.During the performance,children were also instructed to elevate their trunk until the elbows made contact with the thighs and then return to the starting position by lowering their shoulder blades to the mat.Children were asked to perform as many sit-ups as possible during the1min test period.The test examiner counted and recorded the number of sit-ups.This measure was assessed for primary school children(Grades3–6)and for junior middle and junior high schoolgirls.

2.3.7.50m×8 shuttle run

This test required the children to run back and forth 8 times along a straight track line between 2 poles set 50m apart.Children were instructed to run at their maximum speed and,at the end of the track line,turn around at a pole in a counterclockwise direction,and run back to the starting line.Each child performed a single trial,and his or her time was recorded to the nearest second.This measure was assessed only in primary school children(Grades 5 and 6).

2.3.8.Standing long jump

Children were instructed to stand with feet together behind a starting line marked on the ground and to vigorously push off with both feet and jump forward as far as possible.The jumping distance was measured from the take-off line to the nearest point of contact on the landing(back of the heels).Three attempts were allowed,with the longest distance jumped used as the measurement(in cm).This measure was obtained for junior middle and junior high school children.

2.3.9.Pull-ups

As an upper-body strength test,children were instructed to perform a series of pull-ups.Assuming an upright position,with a light jump(a lift was given,if needed,by the test examiner),children grasped an overhead bar using an overhand grip(palms facing away from the body)with arms fully extended.Children were asked to use their arms to pull the body up until the chin cleared the top of the bar and then lower their body again to a position with the arms extended.The performance was repeated as many times as possible,with the total number of completed pull-ups recorded.This measure was assessed only for junior middle and junior high school boys.

2.3.10.1000m and 800m run

This was a sex-specifi test of endurance.The test involved running 1000m for boys and 800m for girls.Children were instructed to run at their fastest pace on a track line.Walking or slow jogging was allowed as an option for children who were unable to perform the test or had to stop for a rest during the assessment.Each child’s performance time on this test was recorded to the nearest second.This measure was assessed for junior middle and junior high school children.

2.4.Statistical analysis

Data were entered centrally and verifie by a trained group of research staff.Preliminary analyses were conducted to verify data discrepancies and check data distribution.Children’s physical fitnes scores from the 11 fitnes indicators were firs calculated using grade-and sex-specifi weights define by the 2014 revised CNSPFS,and weighted scores were subsequently categorized into the categories of excellent(define as having scores of≥90.0),good(scores 80.0–89.9),pass(scores 60.0–79.9),or no pass(scores<60.0).

Taking the cluster sampling of the PAFCTYS design into account,the physical fitnes data were weighted against clustering of schools and analyzed using the Complex Samples option in SPSS Version 23.0(IBM Corp.,Armonk,NY,USA).Descriptive statistics on the specifi indicators of physical fitnes and prevalence estimates of meeting physical fitnes standards were calculated by school grades(primary,junior middle,and junior high),sex(boy,girl),and residence locales(urban,rural).Because residence information was not available for children in Grades 1–3,64,903 children were excluded in examining urban–rural differences.In addition,no direct comparisons on the physical fitnes indicators were made a cross the 3 school grades due to the lack of consistency in the fitnes measures.

To examine differences in meeting fitnes standards among children,a dichotomized variable was made(no pass(scores<60.0)vs.pass(scores≥60.0)),and logistic regression analyses were used to analyze differences in sex and residence locales for the total sample.Subgroup analyses on not meeting fitnes standards were also by sex and sex within residence locales across school grades(primary,junior middle,and junior high).All analyses controlled for children’s chronologic age.Adjusted odds ratios(aORs)and 95%confidenc intervals(CIs)on the prevalence estimates of not meeting fitnes standards were calculated.The level of significanc was set at an α level of<0.05.No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

3.Results

A total of 171,991 children(89,949 in primary schools,43,996 in junior middle schools,38,046 in junior high schools)aged 6–17 years(11.5±3.4 years,mean±SD)participated in the national fitnes assessment of the 2016 PAFCTYS.Descriptive information on sample sizes and participants’age,height,and weight,shown by school grade,sex,and residence locales,are presented in Table 1.

Complete fitnes data were obtained for 89,949 primary school children on 5 indicators:BMI,VC,50m sprint,sit and reach,and timed rope-skipping.In addition,grade-specifi measures were ascertained for timed sit-ups for59,276 children in Grades 3–6 and for the 50m × 8 shuttle run for 29,025 children in Grades 5–6.For junior middle and junior high school boys,fit nes data were obtained for 40,813 boys for 7 fitnes indicators:BMI,VC,50m sprint,sit and reach,standing long jump,pull-ups(sex-specific)and 1000m run(sexspecific)Data were obtained for 41,229 girls for a similar set of 7 indicators:BMI,VC,50m sprint,sit and reach,standing long jump,timed sit-ups(sex-specific)and 800m run(sex-specific)

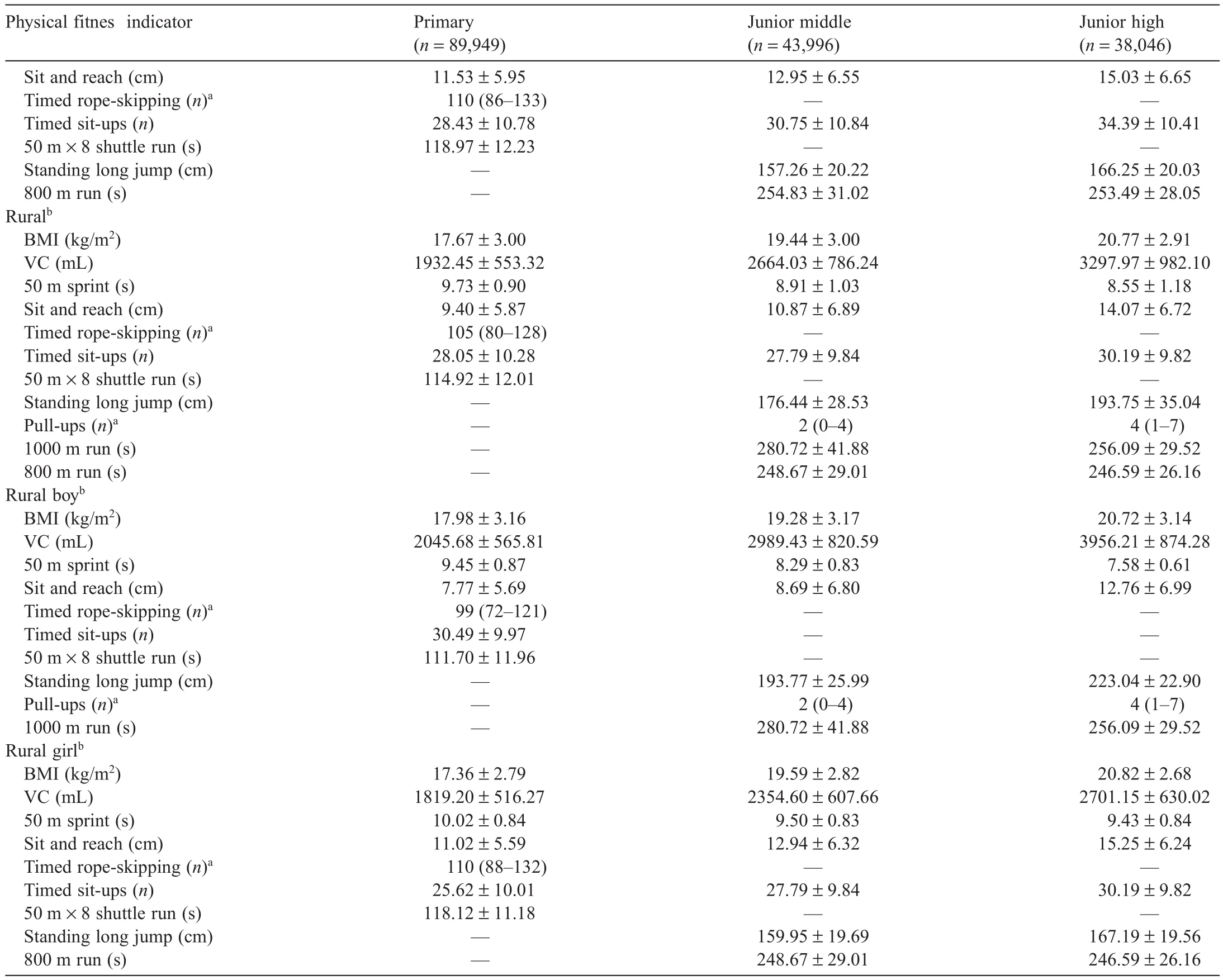

The lack of consistent measures across school grades and sex reflec different fitnes testing standards adopted in CNSPFS.17Table2 shows descriptive statistics on the11 physical fitnes indicators overall and separated by sex and residence locales across school grades.

3.1.Prevalence estimates

Prevalence estimates(data not shown)from the 2016 PAFCTYS show that,overall,more than 90%of Chinese school-aged children met the fitnes testing standards,with 5.95% reaching an “excellent”performance mark,25.80%reaching “good”,and 59.90%reaching “pass”.A total of8.35%of the children were marked as “no pass”in their levels of fitnes performance testing.Estimates by sex and residence locales across the 3 school grades in the study are shown in Table 3.

3.2.Differences by sex and sex within residence locale

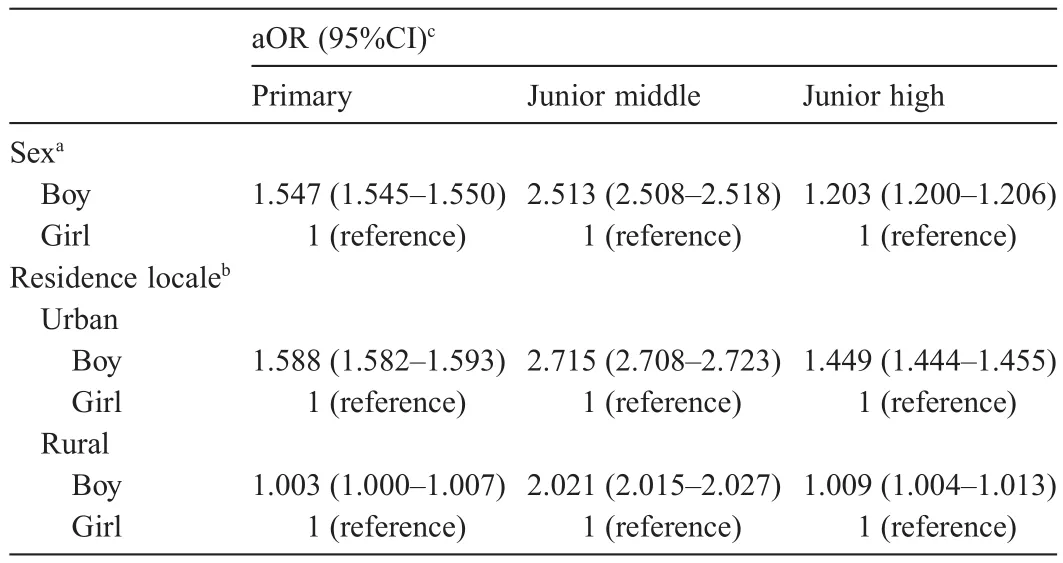

Results from the whole sample(data not shown)show that relative to girls,boys(aOR=1.710;95%CI:1.708–1.712)were more likely to not achieve the fitnes performance standards,and that relative to children living in rural locales,children living in urban areas were more likely to not achieve the fitnes standards(aOR=1.298;95%CI:1.296–1.299).Estimates of not meeting fitnes standards by sex and sex within residence locale across school grade are shown in Table 4.Largely consistent with the estimates generated from the total sample,results indicate that,relative to girls,boys in primary,junior middle,and junior high schools were more likely to not meet the fitnes standards.Within the residence locale strata,with the exception of the in significan estimate on primary schoolboys and girls living in rural areas(p=0.09),boys living in urban areas a cross all3 school grades were more likely to not meet the standards compared to girls.

4.Discussion

The 2016 PAFCTYS fitnes assessment data,which use new ly revised standards,19show that a relatively small percentage of Chinese school-aged children achieved an “excellent”(5.95%)or “good”(25.80%)mark in their overall physical fitnes performance.A significan number of children(59.90%)were marked as “pass”.Approximately 8%of the children assessed in 2016 received a“no pass”mark.Significan sex and urban–rural differences exist among children in meeting fitnes standards,with more school boys not achieving fitnes standards compared to girls,and children living in urban areas being less likely to achieve fitnes standards than those living in rural areas in China.

With the exception of a few national reports issued between 2005 and 2014,10-12there have been few recently published studies or reports in China on physical fitnes among schoolaged children.Using the PAFCTYS data,our report provides the most recent updates on the prevalence of Chinese children meeting physical fitnes standards.Our finding indicate that the prevalence of meeting minimum fitnes standards remains low.Most notably,only about 6%of the children in thePAFCTYS achieved an “excellent”fitnes status,which points to the major public health challenge materializing from the nation’s Healthy China 2030goal of achieving25% “excellent”performance in physical fitnes among Chinese youth.20

Table2(continued)

The low prevalence of “excellent”performance corresponds to the continued and chronic trend of physical inactivity or sedentary behaviors among Chinese children,leading to an epidemic of obesity11,14,21and low,unchanged levels of physical activity among Chinese school-aged children.13,18An early report on physical fitnes showed a 2-decade decline in children’s fitness9and another study,the 2010 National Physical Fitness and Health Surveillance,showed a low level of physical activity,with about 77%of primary and junior middle school children failing to meet the recommendations.22Estimates from the 2016 PAFCTYS provide additional evidence suggesting that the nation’s overall physical fitnes level among school children remains low,with more than 8%of the population failing to pass the current fitnes standards.The results from this study and other studies on physical activity,physical inactivity,and obesity speak collectively to the urgent need for school-based public health interventions to improve the current status of physical health among Chinese children.

4.1.Strengths and weaknesses

This study has some notable strengths.First,we used the most up-to-date fitnes assessment requirements and standards,19which are specificaly tailored toward children in different school grades.Therefore,the estimates presented provide the most comprehensive and recent data available and may help serve as a milestone for future annual assessment efforts and baseline estimates for tracking and evaluatingchanges over time.Second,unlike previous large-scale national fitnes assessments,10-12the PAFCTYS employed a rigorous methodology,which included the use of established assessment protocols,quality control of data collection,and measures that were taken by trained fitnes test examiners(rather than by physical education teachers,as has been routinely done in othernational surveys).Finally,the PAFCTYS provided wide national coverage of cities and regions(including Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps,an independent division within Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region),increasing the representativeness of the Chinese school student population and the generaliz ability of the findings

Table3 Prevalence of meeting physical fitnes standards(“excellent”,“good”,“pass”,or “no pass”)overall and separated by sex and residence locale across school grades,from the2016Physical Activity and Fitness in China—The Youth Study(%).

Table4 Odds of not meeting Chinese fitnes standards among Chinese school-aged children by sex and sex within residence locale across school grade.

There are some major limitations of the study that should be noted.First,as was the case in previous reports,10-12data collected from the 2016 PAFCTYS only provided a snapshot of fitnes performance levels among Chinese school-aged children.Future efforts are needed to measure and track trends in children’s fitnes levels across time.Second,due to the lack of a standardized test protocol and differences in test measures,it is impossible to make a meaningful comparison between the PAFCTYS prevalence data and other domestic4,10-12and international studies.23Relatedly,the use of grade-and sex-specifi fitnes test standards may have been confounded with children’s chronologic age.Therefore,the current estimates should be interpreted with this caution in m ind.Third,the lack of survey information from children in Grades 1–3 may have significant y reduced the generalizability of the study findings Last but not least,narrow CIs were found around aOR estimates.While these may indicate accuracy and precision in the estimates,it is also plausible that the sample weights used in this study may have resulted in low variance in the fitnes data.Because the PAFCTYS used a multistage sampling scheme,the sampling weights applied to account for cluster sampling may not have fully taken into account all aspects of the sampling design to adjust for probabilities of sample selection,differential sampling,and nonresponse that are required to produce nationally representative estimates.This is an issue that needs to be addressed in future sampling designs in order to draw valid conclusions about population fitnes from sample data.

4.2.Future directions for the fiel

Major efforts are needed to improve fitnes standards,strengthen assessment methodologies,and expand know ledge of fitnes testing.First,future research needs to refin and standardize sex-and grade-specifi fitnes test items.This effort will allow direct comparisons across various assessments.Second,criterion-related validation studies are needed to provide validity evidence of current fitnes standards.There is also a concomitant need to develop stringent measurement protocols and weighting procedures for assessing body composition,aerobic fitness and musculoskelet al fitnes and to establish training requirements and certificatio programs for test examiners and administrators.Third,with continuing efforts and plans for collecting annual fitnes surveillance data,there is a need to examine temporal changes in fitnes and its relationship to change in health and physical activity among school children.Finally,a more finey grained analysis of children’s fitnes levels by various demographics(e.g.,age,family socioeconomic status,school PA resources,regions of residence)is needed to help identify subgroups of children at health risk,which may aid the development of prevention and intervention efforts.

4.3.Public health implications

The finding in this study that an extremely low proportion of Chinese children met the CNSPFS “excellent”fitnes standard and 8%of them failed to pass the fitnes standard in 2016 highlight the significanc of the low level of fitnes among the nation’s school children.To put these numbers in a broad perspective,it means that,among 166million Chinese schoolaged children in 2016,24only about10million of them achieved an “excellent”fitnes mark and more than 13 million were unable to meet the currently established fitnes performance standards.These estimates speak to the major public health challenge that school educators and policy-makers face in achieving the nation’s target goal of having 25%of school-age children meet the “excellent”fitnes standard by 2030.20Thus,as the nation works toward its health goal of improving children’s physical fitness the estimates presented herein suggest the need to accelerate the public health effort in developing and implementing school physical education policies that will improve the level of Chinese school children’s health and fitness The finding also suggest that schools should develop and provide physical activity interventions that will create opportunities for children,especially boys and children attending urban schools,to engage in physical activity and participate in fitness enhancing programs both in school environments and non school(i.e.,sports facility,neighborhood,community)environments.

5.Conclusion

Overall,approximately 6%of Chinese school-aged children achieved an excellent fitnes standard in 2016,and about 8%of them did not meet CNSPFS standards.School boys and children living urban areas were more likely to not meet minimum fitnes performance levels.Corroborating the evidence from previous reports,the overall fitnes levels among Chinese children remain low,and thus it is important to continue surveillance and develop school-and community-based policies and interventions aimed at increasing physical activity and improving the fitnes of school-aged children in the Mainland of China.

Acknowledgment

This work is supported by the Key Project of the National Social Science Foundation of China(No.16ZDA227).

Authors’contributions

ZZ performed data analysis and drafted the article;YY and ZK were involved in the conceptualization of the paper and participated in coordinating the fitnes portion of the PAFCTYS project;YZ and JZ conceived of the current study,supervised all aspects of its implementation,data interpretation,and drafted the article.All authors have read and approved the fina version of the manuscript,and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendix:Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2017.09.003

1.Ortega FB,Ruiz JR,Castillo M J,Sjostrom M.Physical fitnes in childhood and adolescence:a powerful marker of health.Int J Obes 2008;32:1–11.

2.Donnelly JE,Castelli D,Hillman CH,Castelli D,Etnier JL,Lee S,et al.Physical activity,fitness cognitive function,and academic achievement in children:a systematic review.Med Sci Sports Exerc 2016;48:1223–4.

3.Chaddock L,Hillman CH,Pontifex MB,Johnson CR,Raine LB,Karmer AF.Childhood aerobic fitnes predicts cognitive performance one year later.J Sports Sci2012;30:421–30.

4.Shang X,Liu A,LiY,Hu X,Du L,Ma J,et al.The association of weight status with physical fitnes among Chinese children.Int J Pediatr 2010;515414:2010.doi:10.1155/2010/515414

5.LaVigne T,Hoza B,Smith A,Shoulberg EK,Bukowski W.Associations between physical fitnes and children’s psychological well-being.J Clin Sport Psych 2016;10:32–47.

6.Cottrell LA,Northrup K,Wittberg R.The extended relationship between child cardiovascular risks and academic performance measures.Obesity(Silver Spring)2007;15:3170–7.

7.Davis CL,Cooper S.Fitness,fatness,cognition,behavior,and academic achievement among overweight children:do cross-sectional associations correspond to exercise trial outcomes?Pre Med 2011;52(Suppl.1):S65–9.

8.Chaddock L,Neider MB,Lutz A,Hillman CH,Karmer AF.Role of childhood aerobic fitnes in successful street crossing.Med Sci Sports Exerc 2012;44:749–53.

9.Carnethon MR,Gulati M,Greenland P.Prevalence and cardiovascular disease correlates of low cardiorespiratory fitnes in adolescents and adults.JAMA 2005;294:2981–8.

10.Research Group on Chinese School Students Physical Fitness and Health.Report on the physical fitnes and health surveillance of Chinese school students in 2005.Beijing:Higher Education Press;2007.[In Chinese].

11.Research Group on Chinese School Students Physical Fitness and Health.Report on the physical fitnes and health surveillance of Chinese school students in 2010.Beijing:Higher Education Press;2012.[in Chinese].

12.Research Group on Chinese School Students Physical Fitness and Health.Report on the physical fitnes and health surveillance of Chinese school students in 2014.Beijing:Higher Education Press;2016.[in Chinese].

13.Cui Z,Hardy LL,Dibley MJ,Bauman A.Temporal trends and recent correlates in sedentary behaviours in Chinese children.Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act2011;8:93.doi:10.1186/1479-5868-8-93

14.Liu Y,Tang Y,Cao ZB,Chen PJ,Zhang JL,Zhu Z,et al.Results from Shanghai’s(China)2016 Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth.J Phys Activ Health 2016;13(Suppl.2):S124–8.

15.Wang C,Chen P,Zhuang J.A national survey of physical activity and sedentary behavior of Chinese city children and youth using accelerometers.Res Q Exerc Sport 2013;84(Suppl.2):S12–28.

16.Sun H,Ma Y,Han D,Pan C,Xu Y.Prevalence and trends in obesity among China’s children and adolescents,1985–2010.PLoS One 2014;9:e105469.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0105469

17.Zong XN,Li H.Physical growth of children and adolescents in China over the past35 years.Bull World Health Org 2014;92:555–64.

18.Fan X,Cao ZB.Physical activity among Chinese school-aged children:national prevalence estimates from the 2016 Physical Activity and Fitness in China—The Youth Study.J Sport Health Sci 2017;6:388–94.

19.Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China.Notice of the Ministry of Education on the National Student Physical Fitness Standard (Revised 2014).Available at:http://www.moe.edu.cn/s78/A17/twys_left/moe_938/moe_792/s3273/201407/t20140708_171692.htm l;2014[accessed 01.08.2017].

20.Central Committee of the Communist Party of China,State Council of China.Healthy China 2030 Blueprint Guide.Available at:http://news.xinhuanet.com/health/2016-10/25/c_1119786029.htm; 2017 [accessed 01.08.2017].

21.Cai Y,Zhu X,Wu X.Overweight,obesity,and screen-time viewing among Chinese school-aged children:national prevalence estimates from the2016 Physical Activity and Fitness in China—The Youth Study.J Sport Health Sci2017;6:404–9.

22.Zhang X,Song Y,Yang TB,Zhang B,Dong B,Ma J.Analysis of current situation of physical activity and influencin factors in Chinese primary and middle school students in 2010.Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2012;46:781–8.[in Chinese].

23.Tremblay MS,Shields M,Laviolette M,Craig CL,Janssen I,Connor Gorber S.Fitness of Canadian children and youth:results from the 2007–2009 Canadian Health Measures Survey.Health Rep 2010;21:7–20.

24.National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China.Statistical Communiqué of the People’s Republic of China on the 2016 National Economic and Social Development.Available at:http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/201702/t20170228_1467424.html; 2017 [accessed 10.08.2017].

杂志排行

Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- The Wingate anaerobic test cannot be used for the evaluation of grow th hormone secretion in children with short stature

- The effects of aerobic exercise training on oxidant-antioxidant balance, neurotrophic factor levels, and blood-brain barrier function in obese and non-obese men

- Correlates of long-term physical activity adherence in women

- Empowering youth sport environments:Implications for daily moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and adiposity

- Overweight,obesity,and screen-time viewing among Chinese school-aged children:National prevalence estimates from the 2016 Physical Activity and Fitness in China—The Youth Study

- Associations between parental support for physical activity and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity among Chinese school children:A cross-sectional study