人类精子染色体非整倍体研究进展

2017-11-22彭向杰黄川范立青卢光琇朱文兵

彭向杰,黄川,范立青,2,卢光琇,2,朱文兵,2*

(1.中信湘雅生殖与遗传专科医院,长沙 410000;2.中南大学基础医学院生殖与干细胞工程研究所,长沙 410000)

人类精子染色体非整倍体研究进展

彭向杰1,黄川1,范立青1,2,卢光琇1,2,朱文兵1,2*

(1.中信湘雅生殖与遗传专科医院,长沙 410000;2.中南大学基础医学院生殖与干细胞工程研究所,长沙 410000)

人类最常见的染色体异常是非整倍体。由于在胚胎发育的早期阶段多数的非整倍体胚胎会停止发育,因此对胚胎的非整倍体率的精确评估多通过对配子的直接研究来进行。大多数非整倍体胚胎的产生,是由于父源或母源性减数分裂中偶然的染色体不分离所导致。本文综述了正常人群的精子非整倍体发生率以及不同种类患者的精子非整倍体率,包括不育患者、体细胞核型异常患者,以及暴露于某些有害的环境或生活方式中的个体;并对精子非整倍体率升高的临床影响进行讨论。

非整倍体; 减数分裂; 染色体不分离; 精子

(JReprodMed2017,26(11):1109-1113)

人类最常见的染色体异常是非整倍体(包括单体和三体)。在新生儿以及自发性流产的胎儿中,性染色体非整倍体均比常染色体非整倍体更为常见。据估计,非整倍体胚胎占全部妊娠的5%[1]。人类非整倍体胚胎中,仅13-三体、18-三体、21-三体及包括X染色体单体在内的性染色体非整倍体能够存活。多数非整倍体胚体在胚胎发育早期阶段即死亡,往往发生在临床检出之前,表现为自然流产、不育或不孕,因此决定了只能直接研究配子对胚胎非整倍体率进行精确评估。

一、正常人群精子非整倍体水平

在过去30余年中,对人精子非整倍体的研究主要通过以下途径:(1)在体外将人精子与去透明带的仓鼠卵融合,然后进行精子染色体核型分析[2],或(2)用多色荧光原位杂交(FISH)实验分析间期精子核。在这些研究中,由于无法区分制片过程中人为造成的染色体丢失或者杂交失败所造成的缺体,则通常对精子非整倍体率进行保守的估计,即二体率的两倍。

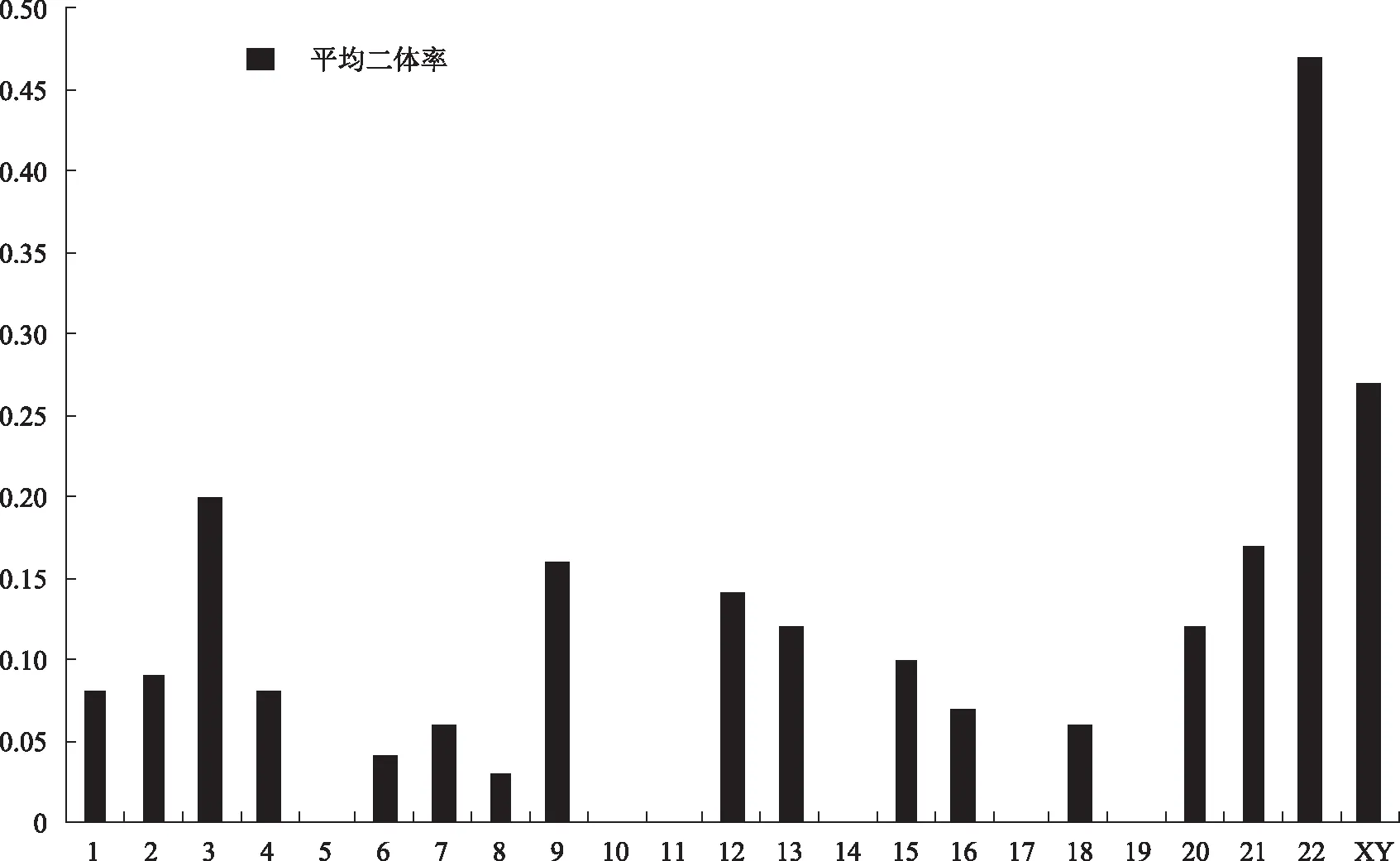

最近,Templado等[3]对388位健康志愿者(18~80岁)精液进行FISH实验所得出的非整倍体率进行综述。其纳入标准如下:志愿者例数不少于5人、每个人每套探针按严格的计数标准计数10 000个精子的研究,汇总描述了精子中18条染色体的二体情况(图1)。对于单条染色体来说,平均的二体率大约是0.1%,总的非整倍体率估计为4.5%(2×2.26),比精子核型分析所得结果(1.8%)要高[4-5]。这一综述同时注意到,21号染色体(0.17%)与性染色体(0.27%)出现非整倍体的情况要比平均值高出2~3倍。与此类似,健康男性精子核型分析中这些染色体的二体情况亦最为常见[4-5]。此外,在减数分裂研究中,21号染色体和性染色体配对体在精母细胞间期Ⅰ分离成单价染色体,在精母细胞间期Ⅱ形成二体的几率更高[6]。这是因为二价的21号染色体及性染色体配对区域最小,而且在减数分裂Ⅰ通常表现出单一交叉[7],因此,它们更容易发生染色体不分离。

图1 用多色FISH分析对健康个体进行的实验所得每一条精子染色体的平均二体率[3]

近几年,关于精子全染色体组非整倍体率或二体率的研究鲜有报道。慕尼黑一家研究机构发表了全染色体组研究结果[8],但研究包含的例数十分有限。这也提示,制定精子全染色体组非整倍体率的参考值十分迫切。

此外,近些年辅助生殖技术以及治疗勃起障碍的新药的应用使得高龄男性有了成为父亲的可能。因此,为了评估后代遗传风险,年龄对精子非整倍体的影响的研究受到了重视。然而,到目前为止暂未发现年龄增长对精子二体率的潜在影响[9-10]。

二、不育患者的精子非整倍体率

通常来说,不育患者的精子非整倍体率显著增高,且非整倍体率随男性因素的不育程度严重性而增加。在对6个辅助生殖中心的319名咨询生育问题的患者进行回顾性研究的过程中,Sarrate等[11]发现这一群体的性染色体二体率较正常值高2~3倍,21号染色体非整倍体及二倍体率亦增高3倍。在与异常非整倍体率水平相关的精液参数中,少精症与非整倍体率增高相关,特别是严重的少精子症(性染色体二体率升高2~6倍,21号染色体二体率升高4倍)[12];而严重的非梗阻性少精子症性染色体非整倍体率为升高4倍[13]。在非梗阻性弱精症患者中也有报道其睾丸精子的非整倍体率升高(性染色体二体率升高2~4倍,21号染色体二体率升高4倍)[14]。

但是,关于精子活力与精子非整倍体之间的关系暂无定论:Sarrate等[11]表明精子活力低下与精子非整倍体率升高之间并无关联。但是其他研究者[15]的研究结果则表明二者之间有一定的联系。

对于精子形态而言,各种畸形精子症的患者性染色体二体率升高2~4倍,非整倍体率升高2~3倍[16-19]。然而,Sarrate等[11]并未发现畸形精子症与非整倍体之间的关系,但仅分析了17例畸形精子症患者。其他严重的精子形态异常,如大头多尾畸形精子综合征(占不育男性患者的1%)与对照组相比非整倍体水平明显升高(10~30倍),另有20%~40%的为二倍体、三倍体及四倍体[20]。据Morel等[21]报道,圆头精子症患者(占不育男性患者的1%)二体率稍有升高(性染色体2~3倍),但是Brahem等[19]在圆头精子患者中发现所有染色体的二体率均有显著升高(8~10倍)。

三、异常核型患者的精子非整倍体率

核型异常患者通常患有不孕及因复发性自然流产而难以获得妊娠,异常表现包括精子密度低下、精子非整倍体率升高等。通常,在这些患者中观察到的精子非整倍体率低于由减数分裂中三价体或四价体所导致的染色体配对异常所推导的理论值。

在非镶嵌型克氏综合征(XXY)中,首例报道的患者性染色体非整倍体率为25%[22],平均为6%[23]。因此,可以推测,在非镶嵌型患者中有一些XXY细胞可以起始并完成减数分裂,产生性染色体三体。在XY/XXY镶嵌型个体中,性染色体非整倍体平均值接近3%。大多非镶嵌型XYY患者外周血性染色体二体率升高,平均为4.2%[24]。在2007年由Gonzalez-Merino等[25]报道的一例患者中,XY二体高达19%,YY二体高达16.7%。

在男性倒位携带者中,不平衡配子可能占到20%~77%[26]。在一篇综述中,Benet等[27]报道了经仓鼠实验研究发现平均55.3%的倒位不平衡配子,而经FISH验证得到的结果为53.5%。对罗氏易位携带者来说,不平衡配子预估值为66%,而实际研究中发现不平衡配子占1%~36%(平均15%)[28-29]。

四、生活方式及职业暴露对精子非整倍体的影响

生活方式、环境及职业暴露均可能导致精子非整倍体升高。不过因为剂量、研究对象的年龄、个体差异、暴露的时间和长度等等并不统一,这些因素之间难以进行比较,而且生活方式和职业暴露的混合效应通常难以分离。

最近的研究结果表明[30-35],尽管精子非整倍体和以上因素之间出现明显的关联,染色体二体率仅比未暴露于以上因素者升高1.5~3倍,大部分研究对象未达2.5倍。这是因为生活方式和其他暴露可能是暂时的,因此个体的精子非整倍体率可能经常变化。

在吸烟者中可见精子非整倍体率略有升高,这是一个广为人知的非整倍体诱发因素。据报道13-二体升高了3倍[30],X-二体升高1.5倍[31],Y-二体升高2倍[32],XY二体升高2倍[33];但是Shi等[30]于2001年发现吸烟与性染色体非整倍体之间并无联系。由于缺少研究,饮酒对精子非整倍体的影响并不明确。Robbins等[34]曾报道了暴露于硼中的饮酒的工人XY二体率升高(1.38倍)。在之前的研究中,Robbins等[31]在一项对中国人的研究中发现,酒精摄入与XX二体之间有显著线性关系。Xing等[35]研究了职业暴露于苯的效应,报道了在低水平暴露的情况下,YY二体轻微升高(1.2倍),而在暴露于高水平苯的情况下,XX二体升高2.8倍。XY二体及总性染色体二体同样受到影响,但其值在中等水平。

大量农药释放到环境中,因此大多数人都有不同程度的暴露。一般的农药污染并不会导致精子非整倍体率的改变[36-37],而氰戊菊酯(杀灭菊酯)污染则会使性染色体二体率升高1.9倍,18号染色体二体率升高2.6倍[38]。相似地,西维因(胺甲萘)使性染色体二体率升高1.7倍,18号染色体二体率升高2.2倍[39]。多氯联苯及p,p ′-DDE均轻微升高性染色体二体率[40]。

Young等[41]评估了营养性叶酸、锌及抗氧化剂的摄入。发现食用叶酸的个体中XX二体率发生率轻微下降(-0.75倍),而口服锌与抗氧化剂并不影响精子非整倍体。

五、精子非整倍体率要多高才能导致后代非整倍体率的升高

一些实验室集中研究了经父系遗传的Down综合征[42-43]、Turner综合征[44]、克氏综合征[45]患儿父亲的精子非整倍体率。这些研究表明,在所有这三个类型患儿父亲的精子中,21号染色体和性染色体的二体率至少是正常人的两倍。

复发性流产的男性精子非整倍体与对照组相比,精子性染色体二体率明显增高(2.3倍)[46]。至少在某些病例中,父源性非整倍体后代或复发性流产与精子非整倍体水平的升高有关,这些例子提示需要制定一个临床上的上限值,即精子非整倍体率需多高才能导致后代的非整倍体率升高。

六、精子非整倍体率升高的临床影响

目前在辅助生殖领域,男女双方受到的重视程度并不平等,这一情况在ICSI技术的出现和逐步完善之后更加严重,尤其是“只要一个活精子,就能让你成功做父亲”这句广告语变得耳熟能详之后。但实际上ICSI在一定程度上解决了不少严重少弱精子症患者的生育难题,使其能用上自己的精子,生育生物学上属于自己的后代,而不是使用供精;但是,在多年的临床实践中,同样也有为数不少的严重少弱精子症患者在经历多次ICSI之后仍无法获得正常的妊娠,而又不甘心或不被允许使用供精,随着男女双方年龄的增长,治疗的黄金时期亦被耽误。

这些情况提出:在ICSI操作过程中,如何确保所选取的严重少弱精子症患者的精子从内(内部染色体数量)到外(外部形态)都是正常的?外部形态可以通过更高放大倍数的显微镜来实现,如精子形态学选择后卵胞浆内显微注射(IMSI);但是内部的染色体情况,尚需额外的检查与评估,如FISH技术。对于通过全染色体组FISH技术评估后全染色体组非整倍体率偏高较为严重的患者,是否可以考虑更换方案(如全供精或者半供精)?毕竟,能使患者成功妊娠,是所有辅助生殖领域临床工作者的终极目标。

另外建议,对于严重少弱精子症多次行ICSI未成的患者,考虑纳入全染色体组非整倍体率检查作为其选择供精的指征之一。如果患者的全染色体组非整倍体率为10%,从百分比这个相对值来看并不见得多严重,但是其一次排精(假设总数1 000万个精子)中就有100万个非整倍体精子,这个绝对数值不容忽视。在患者充分知情同意的情况下,可以提供供精方案。

[1] Hassold T,Hunt P.To err(meiotically) is human:the genesis of human aneuploidy[J].Nat Rev Genet,2001,2:280-291.

[2] Martin RH,Balkan W,Burns K,et al. The chromosome constitution of 1000 human spermatozoa[J].Hum Genet,1983,63:305-309.

[3] Templado C,Vidal F,Estop A.Aneuploidy in human spermatozoa[J].Cytogenet Genome Res,2011,133:91-99.

[4] Templado C,Marquez C,Munne S,et al. An analysis of human sperm chromosome aneuploidy[J].Cytogenet Cell Genet,1996,74:194-200.

[5] Templado C,Bosch M,Benet J.Frequency and distribution of chromosome abnormalities in human spermatozoa[J].Cytogenet Genome Res,2005,111:199-205.

[6] Uroz L,Templado C.Meiotic non-disjunction mechanisms in human fertile males[J].Hum Reprod,2012,27:1518-1524.

[7] Laurie DA,Hulten MA.Further studies on bivalent chiasma frequency in human males with normal karyotypes[J].Ann Hum Genet,1985,49(Pt 3):189-201.

[8] Neusser M,Rogenhofer N,Dürl S,et al. Increased chromosome 16 disomy rates in human spermatozoa and recurrent spontaneous abortions[J].Fertil Steril,2015,104:1130-1137.

[9] Buwe A,Guttenbach M,Schmid M.Effect of paternal age on the frequency of cytogenetic abnormalities in human spermatozoa[J].Cytogenet Genome Res,2005,111:213-228.

[10] Fonseka KG,Griffin DK.Is there a paternal age effect for aneuploidy?[J].Cytogenet Genome Res,2011,133:280-291.

[11] Sarrate Z,Vidal F,Blanco J.Role of sperm fluorescent in situ hybridization studies in infertile patients:indications,study approach,and clinical relevance[J].Fertil Steril,2010,93:1892-1902.

[12] Durak AB,Aras I,Can C,et al. Exploring the relationship between the severity of oligozoospermia and the frequencies of sperm chromosome aneuploidies[J].Andrologia,2012,44:416-422.

[13] Mougou-Zerelli S,Brahem S,Kammoun M,et al. Detection of aneuploidy rate for chromosomes X,Y and 8 by fluorescence in-situ hybridization in spermatozoa from patients with severe non-obstructive oligozoospermia[J].J Assist Reprod Genet,2011,28:971-977.

[14] Sun F,Mikhaail-Philips M,Oliver-Bonet M,et al. Reduced meiotic recombination on the XY bivalent is correlated with an increased incidence of sex chromosome aneuploidy in men with non-obstructive azoospermia[J].Mol Hum Reprod,2008,14:399-404.

[15] Aran B,Blanco J,Vidal F,et al. Screening for abnormalities of chromosomes X,Y,and 18 and for diploidy in spermatozoa from infertile men participating in an in vitro fertilization-intracytoplasmic sperm injection program[J].Fertil Steril,1999,72:696-701.

[16] Gole LA,Wong PF,Ng PL,et al. Does sperm morphology play a significant role in increased sex chromosomal disomy? A comparison between patients with teratozoospermia and OAT by FISH[J].J Androl,2001,22:759-763.

[17] Templado C,Hoang T,Greene C,et al. Aneuploid spermatozoa in infertile men:teratozoospermia.[J].Mol Reprod Dev,2002,61:200-204.

[18] Tang SS,Gao H,Zhao Y,et al. Aneuploidy and DNA fragmentation in morphologically abnormal sperm[J].Int J Androl,2010,33:e163-e179.

[19] Brahem S,Elghezal H,Ghedir H,et al. Cytogenetic and molecular aspects of absolute teratozoospermia:comparison between polymorphic and monomorphic forms[J].Urology,2011,78:1313-1319.

[20] Perrin A,Morel F,Moy L,et al. Study of aneuploidy in large-headed,multiple-tailed spermatozoa:case report and review of the literature[J].Fertil Steril,2008,90:1201-1213.

[21] Morel F,Douet-Guilbert N,Moerman A,et al. Chromosome aneuploidy in the spermatozoa of two men with globozoospermia[J].Mol Hum Reprod,2004,10:835-838.

[22] Estop AM,Cieply KM,Wakim A,et al. Meiotic products of two reciprocal translocations studied by multicolor fluorescence in situ hybridization[J].Cytogenet Cell Genet,1998,83:193-198.

[23] Tempest HG.Meiotic recombination errors,the origin of sperm aneuploidy and clinical recommendations[J].Syst Biol Reprod Med,2011,57:93-101.

[24] Blanco J,Egozcue J,Vidal F.Meiotic behaviour of the sex chromosomes in three patients with sex chromosome anomalies(47,XXY,mosaic 46,XY/47,XXY and 47,XYY) assessed by fluorescence in-situ hybridization[J].Hum Reprod,2001,16:887-892.

[25] Gonzalez-Merino E,Hans C,Abramowicz M,et al. Aneuploidy study in sperm and preimplantation embryos from nonmosaic 47,XYY men[J].Fertil Steril,2007,88:600-606.

[26] Martin RH,Spriggs EL.Sperm chromosome complements in a man heterozygous for a reciprocal translocation 46,XY,t(9;13)(q21.1;q21.2) and a review of the literature[J].Clin Genet,1995,47:42-46.

[27] Benet J,Oliver-Bonet M,Cifuentes P,et al. Segregation of chromosomes in sperm of reciprocal translocation carriers:a review[J].Cytogenet Genome Res,2005,111:281-290.

[28] Frydman N,Romana S,Le LM,et al. Assisting reproduction of infertile men carrying a Robertsonian translocation[J].Hum Reprod,2001,16:2274-2277.

[29] Ogur G,Van Assche E,Vegetti W,et al. Chromosomal segregation in spermatozoa of 14 Robertsonian translocation carriers[J].Mol Hum Reprod,2006,12:209-215.

[30] Shi Q,Ko E,Barclay L,et al. Cigarette smoking and aneuploidy in human sperm[J].Mol Reprod Dev,2001,59:417-421.

[31] Robbins WA,Vine MF,Truong KY,et al. Use of fluorescence in situ hybridization(FISH) to assess effects of smoking,caffeine,and alcohol on aneuploidy load in sperm of healthy men[J].Environ Mol Mutagen,1997,30:175-183.

[32] Rubes J,Lowe X,Moore DN,et al. Smoking cigarettes is associated with increased sperm disomy in teenage men[J].Fertil Steril,1998,70:715-723.

[33] Naccarati A,Zanello A,Landi S,et al. Sperm-FISH analysis and human monitoring:a study on workers occupationally exposed to styrene[J].Mutat Res,2003,537:131-140.

[34] Robbins WA,Elashoff DA,Xun L,et al. Effect of lifestyle exposures on sperm aneuploidy[J].Cytogenet Genome Res,2005,111:371-377.

[35] Xing C,Marchetti F,Li G,et al. Benzene exposure near the U.S.permissible limit is associated with sperm aneuploidy[J].Environ Health Perspect,2010,118:833-839.

[36] Harkonen K,Viitanen T,Larsen SB,et al. Aneuploidy in sperm and exposure to fungicides and lifestyle factors.ASCLEPIOS.A European Concerted Action on Occupational Hazards to Male Reproductive Capability[J].Environ Mol Mutagen,1999,34:39-46.

[37] Smith JL,Garry VF,Rademaker AW,et al. Human sperm aneuploidy after exposure to pesticides[J].Mol Reprod Dev,2004,67:353-359.

[38] Xia Y,Bian Q,Xu L,et al. Genotoxic effects on human spermatozoa among pesticide factory workers exposed to fenvalerate[J].Toxicology,2004,203:49-60.

[39] Xia Y,Cheng S,Bian Q,et al. Genotoxic effects on spermatozoa of carbaryl-exposed workers[J].Toxicol Sci,2005,85:615-623.

[40] Mcauliffe ME,Williams PL,Korrick SA,et al. Environmental exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and p,p′-DDE and sperm sex-chromosome disomy[J].Environ Health Perspect,2012,120:535-540.

[41] Young SS,Eskenazi B,Marchetti FM,et al. The association of folate,zinc and antioxidant intake with sperm aneuploidy in healthy non-smoking men[J].Hum Reprod,2008,23:1014-1022.

[42] Blanco J,Gabau E,Gomez D,et al. Chromosome 21 disomy in the spermatozoa of the fathers of children with trisomy 21,in a population with a high prevalence of Down syndrome:increased incidence in cases of paternal origin[J].Am J Hum Genet,1998,63:1067-1072.

[43] Soares SR,Templado C,Blanco J,et al. Numerical chromosome abnormalities in the spermatozoa of the fathers of children with trisomy 21 of paternal origin:generalised tendency to meiotic non-disjunction[J].Hum Genet,2001,108:134-139.

[44] Martinez-Pasarell O,Nogues C,Bosch M,et al. Analysis of sex chromosome aneuploidy in sperm from fathers of Turner syndrome patients[J].Hum Genet,1999,104:345-349.

[45] Arnedo N,Templado C,Sanchez-Blanque Y,et al. Sperm aneuploidy in fathers of Klinefelter’s syndrome offspring assessed by multicolour fluorescent in situ hybridization using probes for chromosomes 6,13,18,21,22,X and Y[J].Hum Reprod,2006,21:524-528.

[46] Rubio C,Simon C,Blanco J,et al. Implications of sperm chromosome abnormalities in recurrent miscarriage[J].J Assist Reprod Genet,1999,16:253-258.

[编辑:谷炤]

Research progress on aneuploid of human sperm chromosome

PENGXiang-jie1,HUANGChuan1,FANLi-qing1,2,LUGuang-xiu1,2,ZHUWen-bing1,2*

1.Reproductive&GeneticHospitalofCITIC-XiangYa,Changsha410000 2.InstituteofReproductive&StemCellEngineering,BasicMedicineCollege,CentralSouthUniversity,Changsha410000

The most common chromosomal abnormality in human is aneuploidy.Since the majority of aneuploid embryos cease to develop during the early stages of embryonic development,accurate estimate of aneuploid rate in embryos is mostly carried out by direct studies of gametes.The most of aneuploid embryos are caused by accidental chromosomes non-disjunction in the paternal or maternally derived meiosis.This paper reviews the sperm aneuploid rate in normal men and different types of patients with infertility or somatic chromosome abnormalities,as well as the individuals exposed to harmful environment or lifestyle.The clinical impacts of higher sperm aneuploid rate are also discussed.

Aneuploid; Meiosis; Chromosome non-disjunction; Spermatozoa

10.3969/j.issn.1004-3845.2017.11.012

2017-08-22;

2017-09-13

湖南省重点研发计划项目(2016WK2019)

彭向杰 男,湖南娄底人,硕士,基础医学专业.(*

)