日常建筑,一个反思的实践:阅读张永和

2017-10-20朱剑飞黄华青

朱剑飞 黄华青 译

日常建筑,一个反思的实践:阅读张永和

朱剑飞 黄华青 译

本文阅读张永和自1980年代初至2016年的有关写作,提出一个论点,认为张氏在1990年代末期,在关于设计的基本态度上,有一个突破和一个构架的建立。本文进一步认为,张氏思想构架的基本内涵是人文的、反思的、批判的,也是中国急需的,无论在建筑学还是其他领域。

张永和,基本建筑,材料,建造,1990年代末期,新乡土

尽管我曾在多种场合为张永和写过文章1),包括2004年和2012年非常建筑事务所成立10周年及20周年时,但最近阅读他的新论著及项目,并重读他较早的作品,放在当下所处的新历史时代之下,依然是耳目一新、发人深思的。我想,如今我针对张永和的思想及实践发展,可以提出一个假说。

1 6篇文字:一个突破

这个假说就是,尽管张永和发表了大量文章,参与了眼花缭乱的建筑或其他领域的活动及项目,我们依然可遴选出一组核心文字——集中发表于1996-2000年,它们对于张永和的建筑设计进路的建立过程,是关键且 “完成”的——这条进路对于当时的他来说是崭新的,自此从未远离。那几年,张永和的职业生涯似乎攀上了一座高原或山顶,自此他获得了一种完整的视野,持续至今。例如,对海恩斯·宾尼菲特的援引,就从1998年一直延续到2016年。我认为,这组文字是张永和极其重要的分水岭,亦可帮助我们理解他的思想及喜好。以这几篇文章为基础,我们不难阅读他的其他文章,并定位其各自的位置。不仅如此,他的建成、未建成或在建项目和设计,皆可借由这几篇文章来阅读和分析。

这几篇文章的写作时段,是他刚在中国渡过的最初的创作摸索期(1993-1996)、即将进入实践活跃期之时。它们作于他的两本著作之间:1997年的《非常建筑》(图1)和2002年的《平常建筑:一种基本建筑学》 (图2)。前3篇论文题为《十二月令》《园》与《宅》,收录于第一部著作(是他过去15年中关于叙述性装置和概念设计的文集)的前两部分,分别作为前言和绪论,可视为他的一次思想综述和反思性观察。如果说《园》与《宅》建立了两种基本建筑类型(即不再是装置),那么《十二月令》则建立了一个他将进一步探索的概念框架——其中论述了多个话题,包括:将建筑客体外部化的西方透视法的使用;让观者与世界相互内化的中国绘画;中国绘画及造园文化中“内向的”世界观;将中西方观察方式结合的必要性;设计过程的重要性;设计图纸本身的必要性——“不草的草图”。[1]2)

这组核心论述还包括在第一本书出版后的另外3篇:《文学与建筑》(图3)、《平常建筑》和《向工业建筑学习》(图4),分别发表于1997年、1998年和2000年;后两篇文章亦收录于《平常建筑:一种基本建筑学》(2002)一书中。第一篇文章,张永和探索了文学与建筑的关联(三岛由纪夫、维克多·雨果、翁贝托·艾柯、阿兰·罗伯-格里耶以及评论家罗兰·巴特)。在以罗布-格里耶的实践和巴特的理论分析了“客观文学”之后,他亦探讨了它在建筑学中可能的对应物。张永和探索的是一种“零度建筑”,就像巴特所定义的“零度写作”一样。在这篇论中,张永和第一次明确定义了“基本建筑”的概念:

“如果建筑也拒绝意义……如果建筑的能指所指产生重合,建筑只表达自己。如果建筑也回到基本的时空经验,而不是特定的风格化的审美经验……那么建筑可能成为活人的建筑;如果建筑的每一个细部都被(概念性地)显微,从而超越现实,建筑反而可能成为现实的也是寻常的建筑;如果建筑回到建造,就可能成为建筑的建筑。”[2]3)

在之后一年撰写的《平常建筑》中,张永和针对这一问题做了更清楚的陈述。在我看来,这篇1998年发表的文章可视为一篇宣言。该文提到了几位著名或不那么知名的建筑师,尤其是密斯·凡·德·罗、朱塞佩·特拉尼和海恩斯·宾尼菲特,以及他们各自的代表作:乡村砖宅、但丁纪念堂和巴巴尼克住宅。张永和自己的作品也作为一种衍生尝试而被纳入探讨。这篇文字中,张永和建立了“基本建筑”的核心陈述,以下两段话尤为重要——第一段出现在文章第一部分,论述了密斯的乡村砖宅之后:

“我最终的兴趣并不在于密斯,而是想通过密斯分析一个更广泛的现象:一个将建造而不是理论(如哲学)作为起点的设计实践。也是一种建筑定义:即建筑等于建造的材料、方法、过程和结果的总合。就这个定义而言,建造形成一种思想方法,本身就构成一种理论,它讨论建造如何构成建筑的意义,而不是建造在建筑中的意义。”[3]

1

2

3

Although I have written for the tenth and twentieth anniversary of Yung Ho Chang's office Feichang Jianzhu (FCJZ) in 2004 and 2012, and in other occasions1), a recent review of his new writings and projects, with a re-reading of his older pieces, in a new historical time we find ourselves in today, is refreshing and enlightening. I think I now have a hypothesis on Yung Ho Chang in terms of his development in thinking and practice.

1 Six Essays of the Late 1990s: a Breakthrough

The hypothesis is that, despite the prolific publication of many essays and a dazzling parade of activities and projects architectural and otherwise, there is a single cluster of key essays -published quickly between 1996 and 2000 - that are essential and "completed" in setting up his approach to architecture, something new to him then and something he has not departed from since. Somehow, in his career, Chang had arrived on a plateau or a hilltop, in these few years, and a whole vision was found, which remains today. The reference to Heinz Bienefeld, for example, remains in 1998 as in 2016. I am suggesting that this cluster of essays was a crucial threshold for Chang and is essential for us in understanding his ideas and obsessions. With this few pieces identified, other pieces can be read and their positions understood.Further, his projects and designs, built, unbuilt and yet to-be-built, can also be read and analysed in the light of these few pieces.

These few essays were written after a period of initial practice in China (1993-1996) and before launching into an active practice. They were written between two books of him, one in 1997 and the other 2002, titled respectively as Feichang Jianzhu (Un/conventional Architecture, Fig.1) and Pingchang Jianzhu: for a Basic Architecture (Fig.2). The pieces titled "Shier yueling" (calendar paintings), and "Yuan"(the garden) and "Zhai" (the residence), as a preface and an introduction of part one and two of the first book (a collection of essays over the previous 15 years on narrative installations and conceptual designs),acted as an overview and a reflective observation.If "Yuan" and "Zhai" had established two basic typologies of architecture (i.e. not installations any more), "Shier yueling" had arrived at a conceptual framework that he would explore further - and here he covered on the use of western perspectives that externalizes the architectural object, Chinese paintings that internalize the viewer and the world into each other, an "internal" worldview in Chinese culture in painting and garden design, a need to combine western and Chinese ways of seeing, the importance of design process, and the need for design drawings on their own - "sketches that are not sketchy" (bu cao de caotu).[1]2)

The cluster of key essays also includes three pieces written after the first book. They are Wenxue yu jianzhu (Literature and Architecture, Fig.3),Pingchang jianzhu (Basic Architecture), and Xiang gongye jianzhu xuexi (Learning from Industrial Architecture, Fig.4), published in 1997, 1998 and 2000 respectively; the latter two were reprinted in Pingchang Jianzhu: for a Basic Architecture (2002).In the first piece, Chang explored relations between literature and architecture (as in Yukio Mishima,Victor Hugo, Umberto Eco, Alain Robbe-Grillet, as well as critic Roland Barthes) and, after identifying an "Objective Literature" practiced in Robbe-Grillet and studied in Barthes, asked what an equivalent in architecture would look like. Chang was exploring architecture at degree zero, like Barthes' "writing degree zero". Here, for the first time, Chang was putting forward in clear terms his definition of a"basic architecture":

"If architecture also rejects meaning … and if its signifier and signified become one, architecture then expresses itself only. If architecture also returns to the basic spatial-temporal experience,rather than a particular style …, then architecture can serve people alive; if details of architecture are(conceptually) magnified, to surpass reality, then it becomes reality and normality; if architecture returns to architecture, then it can be an architecture of architecture" (my translation from Chang's original in Chinese).[2]3)

In Pingchang Jianzhu (Basic Architecture) in the following year, Chang made another statement on this, clearer this time. This piece of 1998, in my judgment, should be read as a manifesto. The writing here made reference to a few architects known or not so known, including, importantly,Mies van der Rohe, Giuseppe Terragni and Heinz Bienefeld, as well as their key works, such as Brick Country House, the Danteum, and Babanek House of the three architects respectively. Chang's own works were also discussed as an inspired attempt.In this essay where Chang developed his central statement on his "Basic Architecture", the following two are especially important - the first was after a description of Mies' Brick Country House in the first part of the essay:

"My final interest is not on Mies, but rather a general condition that can be arrived at by studying Mies: a practice that departs not from theory or philosophy but from building and construction. This leads to a definition: architecture is a total sum of the construction of material, method, process and outcome. From this perspective, the logic and the use of construction itself become a method, and a kind of theory on its own, which concerns how meaning in architecture is made through material construction, and not how meaning is constructed in architecture" (my translation).[3]

In the section on Terragni's Danteum that concludes the essay, Chang had written arguably the most beautiful and accurate statement about his"basic architecture":

"... though it was not built, the drawings revealed Terragni's deep and refined thinking in the use of material, construction, form and space. What he had constructed with these is not a building but a poem. … But I don't think the poetics of Danteum comes from a relationship between architecture and poetry. The poetry of Danteum, instead, originates from the poetics of loadbearing stone walls, the poetics of a courtyard, the poetics of stone columns,the poetics of a relationship between columns,the poetics of a change of floor levels, the poetics of the steps, the poetics of a doorway, the poetics of a skylight, the poetics of a rectangular shape,the poetics of a square in shape, the poetics of the right angle for an intersection of two parts, the poetics of a narrow spatial passage, the poetics of glazing, the poetics of glass columns, the poetics of a relationship between columns and the ceiling,the poetics of an interstitial space, the poetics of a stone-paved floor, the poetics of an enclosure, the poetics of a basic architecture" (my translation).[3]34

It is obvious that this "basic architecture"is an austere and tectonic construction in a modernist persuasion. In the following piece Xiang gongye jianzhu xuexi (Learning from Industrial Architecture) of 2000, Chang promoted a pure,autonomous and independent architecture or better "building" - one which "needs no ornament"and is devoid of layers of meaning artificially added. And here, Chang is clear about his support for modernism and is putting forward a succinct description of his "basic architecture":

"In terms of value orientation, modernist architects privileged buildings over architecture, to resist a traditional idea that architecture was more than a mere building. This subversion is both a failure and a success. Firstly, it is a failure, because these architects could not finally escape from architecture. Yet the success is more profound: when the layers of meaning are stripped away, a building is a building on its own, it is an autonomous existence,and is not a tool of signification nor a secondary existence for something else" (my translation).[4]

These six pieces - three published in Feichang Jianzhu (1997) and three after - as written between 1996 and 2000, marked a core of Chang's prolific writings and above all a core of his thinking for design practice. We may add another exceptional piece, written much earlier, to this core - a central essay in forming his approach at a conceptual or methodological level. This is Guocheng sixiang,(Thinking as a Process) written in 1987-1988 when Chang was teaching in the United States.Quoting Michel Foucault's essay on René Magritte's juxtaposition of a painting of a smoking pipe and a text This is not a Pipe, and finding a rewarding understanding of complex relations between a statement and a visual representation, Chang argues that a subversion of a truth statement, a reverse in thinking against an accepted idea, notion or understanding, can be illuminating in a true,positive and creative sense - such a process 'provides a condition for a new work to be initiated'. Reversing or changing in thinking, according to Chang, "is helpful in exposing a problem, … in overcoming a conventional assumption, … in recovering a sense of strangeness".[1]194-197Chang had worked surely in this manner, where a bicycle wheel, a door, a floor, a window, etc, is suspended in their normal or "true"condition, and was subverted and creatively remixed or renewed or reshaped, challenging not only a conventional truth statement, but also artificial ideologies applied onto a building to become architecture. The posture here is critical, in design,in thinking, and in a whole outlook concerning more than a mere business of design.

在文章末尾关于特拉尼的但丁纪念堂的论述之后,或许是张永和关于其“基本建筑”理念最优美、准确的一段陈述:

“……罗马的但丁纪念堂没能建起来,但不难从保存下来的图纸中看到建筑师特拉尼对材料、建造、形态与空间精深的造诣。他用这些质量构成的不仅是建筑而是诗……但我不认为但丁纪念堂的诗意出自于建筑与诗歌的关系。但丁纪念堂的诗意更是石承重墙的诗意,庭院的诗意,石柱的诗意,柱与柱之间关系的诗意,高差的诗意,踏步的诗意,门洞的诗意,天光的诗意,矩形的诗意,方形的诗意,正交的诗意,窄的诗意,玻璃的诗意,玻璃柱的诗意,顶棚与柱之间关系的诗意,缝隙的诗意,石铺地的诗意,围合的诗意,基本建筑的诗意。”[3]34

显然,“基本建筑”是在现代主义信念指引下、一种朴素而建构的建造。在后一篇写于2000年的文章《向工业建筑学习》中,张永和推出了一种纯粹、自治、独立的建筑,或更准确地说是“房屋”——“不需任何装饰”,亦摆脱了人为添加的层层意涵。在此,张永和明确表达对现代主义的支持,也提出了“基本建筑”理念的简明论述:

“就价值判断而言,现代主义建筑师将房屋置于建筑之上,对立于建筑高于房屋的传统观念。这次颠覆既是失败的又是成功的。首先是失败的,因为现代主义建筑师们终究未能摆脱建筑。然而成功更深刻——清除了意义的干扰,建筑就是建筑本身,是自主的存在,不是表意的工具或说明它者的第二性存在。”[4]

以上6篇论文——前3篇刊载于《非常建筑》(1997),后3篇刊载于《平常建筑》,都是于1996-2000年写作的,构成了张永和丰富论著的内核——尤其是他建筑设计思想的内核。我们或可在其中再添加一篇出色的文章,写于更早,这篇文章对于他的理念或方法论进路的形成十分重要。那就是《过程思想》,写于1987-1988年,当时张永和在美国教书。他援引米歇尔·福柯关于雷尼·马格利特将一幅烟斗的油画与“这不是一只烟斗”的文字并置的文章,深刻辨析了真理陈述和视觉表征之间的复杂关系。张永和提出,对真理陈述的颠覆,对公认概念、观点或理解的逆向思考,能够在一种真实、积极、创造性的意义上给人启发——这样的过程“提供了开启新工作的条件”。在张永和看来,逆向或转变性的思考,“能帮助我们暴露问题……克服惯常的预设……重塑一种陌生感。”[1]194-197张永和自己显然也在以这种方式工作,无论是一只自行车轮、一扇门、一层楼板或一扇窗等等,都从常见的、“真实的”状态中剥离,经过推翻和创造性的混合、更新或重塑,不仅挑战了惯用的真理陈述,也颠覆了那些附加在房屋之上、使其成为建筑的人工意识形态。这样一种姿态在设计、思考和他的全部工作中都至关重要——他关注的远不只是一种作为生意的设计实践而已。

4

2 整体脉络

我之所以说1996-2000年的这组文字非常重要,是因为它们出现于张永和个人及职业发展轨迹的特殊时刻。那是张永和15年“学术”研究生涯的末端(从1981年至1996年,他在美国学习、教书,直至1990年代中叶;自1993年开始回到中国试验他的理念);它们也标志着张永和在中国活跃实践期的开启,至今已延续了20余年。尽管1990年代末的这几篇论述总结了他过去15年的诸多思想,但它们更是一次突破、一个转折点,开始探讨一些从未真正探讨过的论题(至少从未明确谈过)——尤其是“基本建筑”的相关概念,让“建筑回到建造,成为建筑的建筑”,“建筑就是建筑本身,是自主的存在”。他的生涯早期研究,主要是藉由装置和概念设计所表达的生活经验叙事;而至1990年代末的这些文章,则完全回到建筑的主题,探讨建造与建筑空间、形式之间的关系——这个问题,是张永和在1990年代末期真正踏入实践生涯之后所必须面对的。那一刻,张永和必须做出一个剧烈、也可能很困难的转折,从罗德尼式、源于AA的对生活的叙事性研究及概念装置研究,转向真正设计实践的完整模式,并适应于其所在的高速发展的经济环境。因此,关于“建筑”应为何物的提法——过去张永和不需回答,如今却必须创造并发展。

1990年代末这次从学术研究到商业实践的转变,也伴随着地缘政治和地缘文化意义上的转型。张永和在1993年回到中国,在太平洋两岸往返一段时间后,于1996年定居北京,开始建筑实践。矛盾的是,当他回到故乡的这一刻,他反而进入、或是被带到了世界面前,并且在一个更高的平台上。自1996年以来在中国的20年实践生涯,对张永和来说也是一趟全球交互之旅:他不仅先后在密歇根大学、哈佛大学、麻省理工学院任教,也获得了AA(伦敦)、the Aedes(柏林)、Gallery MA(东京)及威尼斯双年展的设计委托和展览邀约。在90年代乃至后来,张永和一度是唯一的、或是极少几个来自中国的、能够为西方建筑师及评论家所理解的声音,原因是他曾在美国学习和执教。更关键的是,张永和在过去20年中不仅向西方传递着中国的声音,同时也在中国传播西方的思想。他和其他若干建筑师带到中国的西方当代价值,对于中国这样一个奋力进入国际现代社会的国家来说,有着不可低估的作用。这一点我会在后文再次论述。

5

6

因此,1990年代末期的这几篇论文夹在过去15年和未来20年之间,不仅是分水岭,也是连接点。作为一道分水岭,前后两个时期之间存在着巨大的张力与不同。之前,他的焦点是建立在绘画、文字或空间手段上的日常经验叙事,而从1993年、尤其是1996年开始,则转移至实际项目设计之中。尽管过去的某些关切依然延续或表达于新的设计实践中,但实际上这并不容易,因为一座建筑或城市设计,不可能当作一件纯粹的艺术作品或抽象装置——这样的张力和区别,是应该认识到的。

当然,这一组论文也是一道连接之桥,让过去的理念——尤其是视野和再现的问题、关于基本建筑的客观文学、对于日常生活及其物件的关切——得以在设计实践中继续发挥重要作用。为此,我们需要简要列举张永和在第一阶段的主要关切和主题——尽管它们并未全部进入实际设计之中。从物件到话题来看,这些主题包括:自行车、烟斗、门、楼板、家具、窗户和开洞、框景装置、观看方式、不同文化中的视觉表征、东西文化比较、中国空间的内向性、作为内化空间的园林与庭院、性别关系、谋杀案、侦探小说、建筑的观念艺术、创造过程中的逆向批判思维,以及电影、文学和建筑的关系。尽管这份名单看似冗长而无尽,但关注焦点却是清晰的。它们全都以个体切身经历的日常生活为核心,而对它的叙述则建立在文字、视觉、空间或影像构筑之上。

让我们回到主题。1996-2000年的6篇论文,不仅是对他之前所关切问题的总结,也是对即将开始的设计阶段的基本准则的概述。如果说《十二月令》集合了过去偏向于视觉和文化的主题,《园》与《宅》两篇短文则为下一阶段建立了两种基本建筑类型——真正的建筑必须表达直接、首要的关切。而接下来的3篇论文《文学与建筑》 《平常建筑》和《向工业建筑学习》,则明确了这条思想线索——从客观文学到基本建筑,最终走向自治的现代主义。其中的核心概念是一种让“房屋”理性高于“建筑”文化(经典的、风格驱动的、装饰性的)的基本建筑——这样一种建筑,不表达其他任何概念,只作为一栋实体房屋而存在。基本建筑的四要素是:材料、建造、形式和空间。在张永和看来,以此为准则进行实践的英雄,就是密斯、特拉尼和宾尼菲特。

如今,尽管张永和在过去20年中积累了大量阅历和经验,但他在2016年发表的文章,依然保持着延续性。他最近发表的若干写作中,有两篇尤其重要,其中的两个问题仍是他关切的核心:那就是“看”和“造”——一边是视野和表征,另一边是工艺、材料和建造。《“看”的建造》(图5)是一次巡礼式反思,总结了观看和绘图的工具,以及看、见、知、表达的关系[6]。而更重要的是《对待工艺的四种态度》(图6)这篇文章,展现了张永和对“基本建筑”理念的持续研究:文中,他依次剖析了海恩斯·宾尼菲特、筱原一男、杰弗瑞·巴瓦与西格德·莱弗伦茨的约27座建筑,具有一种全新的开放性和包容性,但依然保持了他的长期兴趣——尤其是宾尼菲特的巴巴尼克住宅(1990)、筱原一男的谷川之家(1974)、莱弗伦茨的瑞典克里潘圣彼得教堂(1966)。张永和对这些项目的赞赏是显而易见的:“假如我自己住在这个房子里,我会祈祷每天都下雨”(称赞巴巴尼克住宅的排水管及混凝土排水槽);“这里有一个疯狂的不对称的壁炉烟囱”;“莱弗伦茨完成各种令人难以置信的建筑细部”;“这座教堂是一个极为美丽的建筑作品”。[7]总体来说,在2016年的这些论文中,张永和对“工艺”和“造”这些词汇的使用看似是新的,因为这是他近年来在同济大学任教所专注的主题;但其中亦反映了他过去20年的不懈探索——“基本建筑”,以及材料和空间的建造诗意。

2 Overall Trajectories

The reason I say this cluster of essays from 1996 to 2000 is important is that they emerged at a particular moment in Chang's personal and professional trajectory. They emerged at the end of a 15-year "academic" research (from 1981 to 1996,when Chang studied in the United States, then taught there, up to the mid-1990s, then began to test ideas in China since 1993); they also marked the beginning of a phase of active practice in China that has lasted by now for two decades. Although the essays of the late 1990s summarized many ideas from the past 15 years, they were a breakthrough or a turning point in that they began to address issues never really addressed before (never so clearly at least) - ideas of a "basic architecture",where "architecture returns to itself and becomes an architecture of architecture", and where "a building is a building on its own, and is an autonomous existence". While the early studies before were about narratives of life experience constituted in installations and conceptual designs, the writings now, in the late 1990s, were about architecture, and about relations between building construction and the space and form of architecture - an issue one has to confront when one steps into real practice as Chang did since the late 1990s. At this moment,Chang had to make a dramatic and probably difficult transition, from a Rodney-inspired, AA-derived narrative study of life and of conceptual devices,into a full mode of real design practice, in a fast developing economy. So, such a formulation, about what "architecture" should be - something Chang didn't need to answer - had to be invented or developed now.

This turning from academic study to commercial practice in the 1990s also coincided with a geopolitical and geo-cultural transition. Chang returned to China in 1993 and, after shuttling across the Pacific for a while, settled down in Beijing to practice in 1996. Paradoxically, from this moment on, when he returned home, he entered or was brought back to the world, this time at a higher platform. Since 1996, the two decades of practice in China for Chang was also a journey of global interactions for him,which witnessed not only professorships at Michigan,Harvard and MIT, but also design commissions and invited exhibitions at venues including the AA, the Aedes, Gallery MA, and Venice Biennale. Chang was for a while the only voice or one of the very few in China that western architects and critics can understand, in the 1990s and after, as he studied and taught in the United States before. The key point to note is that Chang now has acted, for the past two decades, not only a Chinese voice to the west,but also a western voice in China. The western and contemporary values he - and many others - has been bringing into China, a country struggling to move forward to a certain international modernity,cannot be underestimated. On this I will come back soon.

So, sandwiched between the previous 15 years and the following two decades, the key essays of the late 1990s can be read as serving both as a dividing and connecting point. They served as a dividing point in that there were tensions and differences between these two periods. While the focus was on narratives of life experience as constructed in or with painterly, textural and spatial means before,the focus from 1993 and especially 1996 onwards has been design for real commissions. Although the concerns of the past can be brought in or expressed through new designs, it has been in fact not that easy, because a building or an urban design cannot be a pure art work or abstract installation - this tension and this difference must be acknowledged.

For sure, this cluster of essays also served as a connecting bridge where ideas of the past, especially the issues of vision and representation, objective literature in relation to basic architecture, and a care of daily life and its objects, remain important in design practice. For this, we need to brief l y enlist the key concerns and themes Chang had explored in the first stage, even though not all of them can be or have been brought into real designs. Ranging from objects to topics, they include: bicycles,smoking pipes, doors, floors, furniture, windows and openings, devices of framing, ways of seeing,visual representation in different cultures, eastwest cultural comparisons, inwardness in Chinese spatiality, gardens and courtyards as internalizing space, gender relations, murders, detective stories, conceptual art for architecture, subverting or reversing for critical thinking in a creative process, and relations between cinema, literature and architecture. Though the list seems long and endless, the focus is clear. All of them center on the everyday, as experienced by concrete individuals,and a narrative about it as found in textual, visual,spatial or cinematic constructions.

Let us recapture the main point. The six essays of 1996-2000 served both as a summary of the concerns of the past and a framing of basic principles of design for the phase to come. While "calendar paintings" collected the main themes from the past that privileged more for the visual and the cultural,the two short texts on "the garden" and "the residence"established two fundamental architectural typologies for the next stage where real architecture has to be the immediate and primary concern. But the next three essays, Literature and Architecture, for a basic Architecture, and Learning from Industrial Architecture, had clearly established a line of thought,from objective literature to basic architecture, and onto an autonomous modernism. The central idea was for a basic architecture that privileges the rationale of"building" over the culture of "architecture" (classical,style-driven, ornamental) - one which does not speak for something else except itself as a material building.The four elements identified for this basic architecture were: material, construction, form and space. And the heroes who have practiced this way, according to Chang, were Mies, Terragni and Bienefeld.

Today, the essays written by Chang, as published in 2016, remain consistent despite the enrichment and the experience accumulated over the two decades. Of the several pieces recently published, two appear especially important, and two issues remain as core concerns of Chang.They are viewing and making, that is, vision and representation on the one hand, and craft, material and construction on the other. "Kan" de jianzao(Construction Looking, Fig.5) provides a parade of reflections on the devices of viewing and drawing,and the relations between looking, seeing, knowing and representation.[6]But Duidai gongyi de sizhong taidu (Four Positions on Craft, Fig.6) reveals, more importantly, Chang's ongoing study for the "basic architecture": some 27 buildings by Heinz Bienefeld,Kazuo Shinohara, Geoffrey Bawa and Sigurd Lewerentz, were studied one by one, closely, with a new openness and tolerance, but also a persistent interest, especially on Bienefeld's Babanek House(1990), Shinohara's Tanikawa House (1974), and Lewerentz's St. Peter's Church at Klippan of Sweden(1966). Chang's appreciation of these projects is obvious: "If I lived here, I would pray for it to rain everyday" (commending a drain pipe and concrete sinks collecting rain water); "there is a crazy and asymmetrical chimney"; "Lewerentz has completed incredible architectural details"; "this church is extremely beautiful".[7]On the whole, in these writings of 2016, the use of the term "craft" (gongyi)and "making" (zao) seem relatively new as Chang have been teaching at Tongji University of Shanghai in recent years focusing on these themes, yet a long consistency in exploring a "basic architecture" and a poetics of building with materials and spaces remain over the two decades.

若回顾张永和的设计作品,尤其是近年来的项目,会看到一种“新乡土”趋势的出现。“园”(庭院、组群、场地)和“宅”(室内、住房、会所、办公室、公寓和宿舍)这两个基本类型可以从很多项目中找到。而框景、观看、视角的主题,也体现于多座建筑中,尤其是柿子林住宅(2004)、苹果社区售楼中心(2003)、长安运河会所(2015)、上海当代艺术馆设计中心(2016)。对于日常物件惯常使用方式的悬置,可见于车轮、相机盒、窗框、透明楼板、折叠门等,涉及的项目从1996年的“席殊书屋,到2013年的垂直玻璃宅和2016年的上海当代艺术馆设计中心。尽管他持续关注宅、园、景框、日常物件的“误用”、作为中国传统的内化过程,但或许有一个问题是最为重要的——那就是房屋建造中使用和表现出的材料,以及其中涉及的工艺。在这个问题上,可以在项目中看到越来越强的自信和强调:在多处使用的黑色石材,如长安运河会所(2015);以及若干近期项目在墙体和格栅上使用的灰瓷和灰砖,例如在几座文化中心及博物馆-大学项目中,尤其是2017年初中标的巴黎国际大学城的中国基金会大楼[8]。我认为,一种“新乡土”正在崛起;它是一种“基本建筑”,关注实践过程中的材料和建构逻辑,在整体思路上是反思性和批判性的;它同时关注着视觉景框和理性的物质性;它受惠于中国、欧洲文艺复兴及当代世界的智识传统,尤其是空间的内化——作为一条中国的进路。

3 地缘政治关系中的进步力量

如果我的解读是正确的,那么1990年代末期的这几篇文章,或许在张永和整个建筑世界的思考和实践中都起到核心作用。接下来,我们不仅要从内部和语义学意义上,也需借助外部的、地缘政治及全球性的观察视角理解这些文章。内部看来,它们特殊的内容和实体已如前述:个人生活、表征、表达方式、作为建筑语言的建构材料性、作为文学和建筑中的批判性起点的基本或“零度”。这些文章的目的是重新发现日常;它的关切是微观的、私密的、个体的、以人为中心的,而它的批判性则是致力于挑战或颠覆一种真理陈述(例如一个宏大叙事、或一种系统化的意识形态)。

从外部看,论及全球和地缘政治轨迹,从张永和的自传性散文《AA与我》(2016,图7)可见一斑[9]。随着邓小平改革开放,中国人开始到世界各地游学。张永和在美国学习及任教的1981-1996年,学到的应是1970年代欧美的解放性智识文化——至少在建筑学及相关人文学科是如此。除了1960-1970年代克里斯托弗·亚历山大和罗伯特·文丘里的批判和解放思想外,张永和也吸收了一支特别的思想潮流——“叙事建筑”,主要是1970年代在伦敦建筑联盟学院(AA)由伯纳德·屈米、罗宾·埃文斯、罗德尼·普莱斯等人所发展。罗德尼·普莱斯对于张永和是个关键人物,他在1982年来到波尔州立大学任教,并直接教授张永和一门设计课,名为“不确定性实验室:使用、误用和滥用”。这门课上,张永和探讨了自行车的“不确定性”,自此他始终对这些概念和装置很感兴趣,并体现在他的论文和设计中。整体上说,如欲进一步探讨,他的思想中存在一条视觉及文化线索,和一条智识或反思线索。其中一条线索是来自视觉艺术和文化的线索,其主要人物可追溯至罗宾·埃文斯、约翰·贝格和大卫·霍克尼,以及学术意义上的埃尔文·潘诺夫斯基,还有包括马塞尔·杜尚和阿尔弗雷德·希区柯克在内的导演和艺术家。另一条反思和批判的思维线索,从罗德尼·普莱斯和伯纳德·屈米,直接或通过他人间接地延伸至米歇尔·福柯和罗兰·巴特等人。

至于20世纪美国和欧洲的批判及智识传统——聚焦于微观、个体及日常,并以此为基础进行人文主义批评,其中一个重要的源头人物不可避免:瓦尔特·本雅明(1892-1940),尤其是他关于街道、拱廊街、人群、面孔、姿态、摄影、电影、戏剧、悲苦剧和各类视觉艺术的评论(写于1920-1930年代)。我认为,张永和思想的终极源泉是本雅明。从这个意义上说,张永和传达出的信息是人文主义的、反思性的,由此必然会关注1970年代的叙事作品和20世纪早期的建构现代主义;而这种信息的核心,则是对日常生活的微观批评。在中国,邓小平在1970年代末至1980年代大刀阔斧的改革开放带来了全球文化及西方思想浪潮——同时也将张永和等多人的反思性文化实践带入逐步走向开放及现代化的中国。张永和是最早的人物之一,至今仍是建筑领域的核心人物。他不仅是中国面向西方的声音,也是世界走进中国的声音,把在我看来十分必要的进步性思想和价值观,带到这个挣扎着转变、走向某种程度的普世现代性的中国。

综上,张永和的“基本建筑”导向是人文的、反思的、批判的,应视为一种对真诚、勇敢、正直的灵魂的呼唤——在建筑和社会生活领域皆是如此。□

7

/References:

[1] Zhang Yonghe (Yung Ho Chang), Feichang Jianzhu(Un/conventional Architecture), Harbin: Heilongjiang Chubanshe, 1997.

[2] Zhang Yonghe, Wenxue yu jianzhu (Literature and Architecture), Dushu, No. 9, 1997, pp. 68-71, reprinted in Zhang Yonghe, Zuo Wen Ben: Yung Ho Chang Writes, Beijing: SDX publishing house, 2005, pp. 95-104.

[3] Zhang Yonghe, Pingchang jianzhu (basic architecture), Jianzhushi: The Architect, No. 84, Oct 1998, pp. 27-37.

[4] Zhang Yonghe and Zhang Lufeng, Xiang gongye jianzhu xuexi (Learning from Industrial Architecture),Shijie Jianzhu: World Architecture, No. 7, 2000, pp.22-23.

[5] Zhang Yonghe, Zuo Wen Ben: Yung Ho Chang Writes, Beijing: SDX publishing house, 2005, pp. 95-104.

[6] Zhang Yonghe and Zhou Jianjia, "Kan" de jianzao:construct looking, Shidai Jianzhu: Time + Architecture,No. 3, 2016, pp. 28-33.

[7] Zhang Yonghe, Duidai gongyi de sizhong taidu:Bienefeld, Shinohara, Bawa and Lewerentz - four positions on craft, trans. Jiang Jiawei, Chen Dijia,Shidai Jianzhu: Time + Architecture, No. 3, 2016, pp.154-161.

[8]

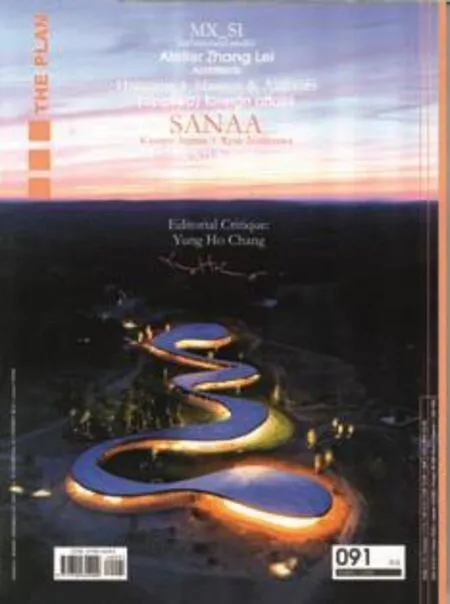

[9] Chang, Yung Ho, The AA and I, The Plan, No. 6-7,2016, pp. 1-4.

[10] Zhu, Jianfei and Hing-wah Chau, Yung Ho Chang:Thirty Years of Exploring a "Design Discourse", Abitare:Zhu (Asian & Chinese edition), No. 32, Oct-Dec 2012,pp. 30-39.

[11] Zhu, Jianfei, Criticality in between China and the West, The Journal of Architecture, Vol. 10, No. 5, Nov 2005, pp. 479-498.

If we review Chang's designs, and especially the recent projects, we witness a "new vernacular"emerging. The two basic typologies, the garden(courts, clusters, fields) and the residence (interiors,houses, clubs, offices, housing and dormitories)are found in many projects. The issues of framing,viewing, and perspectives are addressed in many cases, especially Villa Shizilin, Pingod Sales Center,Chang-An Canal Club, and the psD (power station Design) center, in 2004, 2003, 2015 and 2016 respectively. The suspension of a conventional use of daily objects can be found in the use of wheels, camera boxes, window frames, transparent floors, foldingsliding-doors, in projects ranging from the book-bikestore of 1996 to the vertical glass house and the psD center of 2013 and 2016. While residence, gardening,framing of visions, the "misuse" of daily objects,and internalizing as a Chinese tradition remain as a constant focus, one key concern is arguably the most important - the material employed and expressed in building construction, and the craft of doing so in architecture. In this, we are witnessing an increasing confidence and emphasis: the black stone used in many cases as for example in Chang-An Canal Club of Beijing (2015), and the gray tiles and bricks in the recent projects, for walls and grilles, as in many cultural centers and museum-colleges, and especially in the Maison de la Chine in Paris for CIUP (Cité Internationale Universitaire de Paris), a wining scheme in early 2017[8]. I am suggesting that a "new vernacular" is on the rise; it is a "basic architecture"that cares about materials and the tectonic logic in practice and is Reflexive and critical in outlook; it has a twin focus on visual framing and rational materiality;and it is enriched with intellectual traditions from China, Renaissance Europe and the contemporary world, with a particular interest in internalization in space as a Chinese approach.

3 Critical and Geo-Political

If my reading is correct, then the writings of the late 1990s remain central in the whole architectural universe of Yung Ho Chang in thinking and for practice. Here we need to understand this core writings of 1996-2000 from an internal and semantic as well as an external, geo-political and global point of view. Internally, the specif i c contents and entities are already described above: personal life, representations, means of representation,tectonic materiality as an architectural language,the basic or "degree zero" as a critical point of departure in literature as in architecture. The aim is to rediscover the everyday; and the concern is micro,personal, individual and human-centric, while its criticality here aims at challenging or reversing a truth statement (a grand narrative or a systematic ideology for example).

Externally, in terms of a global and geo-political trajectory, Chang's personal biography and his essay"The AA and I" (2016, Fig.7) reveal a lot[9]. With Deng Xiaoping's opening-up, the Chinese began to travel and study abroad. When Chang studied and taught in the United States from 1981 to 1996, what he learned, I think, was a liberating intellectual culture of the 1970s of American and Europe, at least in the discipline of architecture and the associated humanities. Besides the critical and liberating ideas of Christopher Alexander and Robert Venturi of the 1960s and 1970s, a specific stream absorbed in Chang was the ideas of "narrative architecture"explored mainly at the Architectural Association (AA)of London by figures such as Bernard Tschumi, Robin Evans, and Rodney Place in the 1970s. Rodney Place was a central figure for Chang; he came to Ball State University in 1982 to teach and taught Chang directly,in a studio titled "Lab of Uncertainty: Use, Misuse and Abuse" where Chang explored the "uncertainty"of the bicycle; Chang remained interested in the ideas and the devices ever since, as evidenced in the essays and designs. On the whole, there is a visual and cultural line and an intellectual or ref l ective line, if we like to discover further. One line of inf l uence in visual art and culture can be extended to figures such as Robin Evans, John Berger, and David Hockney and, in terms of intellectual lineage, Erwin Panofsky, as well as directors and artists including Marcel Duchamp and Alfred Hitchcock. Another line of influence in reflective and critical thinking can be extended from Rodney Place and Bernard Tschumi, directly or through others, to Michel Foucault and Roland Barthes.

Of the critical and intellectual tradition in America and Europe of the twentieth century that have focused on the micro, the individual and the everyday, as a base from which to launch a humanistic critique, one absolute source figure stands out: Walter Benjamin (1892-1940), in his writings on streets, arcades, crowds, the face, the gesture, photography, cinema, theater, tragic drama,and the various visual works of art (in the 1920s-30s). I would argue that, intellectually, Chang's ultimate source is Benjamin. In this sense, Chang's message is humanistic and Reflexive, with a certain focus on the narrative of the 1970s and a tectonic modernism from the early twentieth century; while his core message is a micro critique of the everyday.In China, it is Deng Xiaoping's daring project of opening-up in the late 1970s and the 1980s that had brought a global culture and a wave of western ideas, including the reflexive cultural practice of Chang (and many others) into a China gradually opening up and modernizing. Chang was one of the first such figures and remains a key player in the field of architecture. Acting as a Chinese voice in the west, he also acted and still acts as an international voice in China, bringing ideas and values - progressive and much needed in my view -into a China struggling and transforming, towards a certain universal modernity.

In summary, Yung Ho Chang's "basic architecture" is humanistic, Reflexive and critical in orientation, and should be viewed as a call for an honest, brave and upright spirit to come, for both architecture and social life.□

注释/Notes:

1)对张永和整体方法的20周年研究,见参考文献[10]/For a study of Chang's overall approach for a twentieth anniversary review, see Reference [10]; 对在全球背景下受到张永和影响的中国当代建筑的研究,见参考文献[11]/for a study on contemporary Chinese architecture in a global context where Chang played a role, see Reference [11].

2)《院》和《宅》见参考文献[1],《十二月令》(月历绘画)作为扉页出版无页码。/See Reference[1], for "Yuan" (the garden) and "Zhai" (the residence);"Shier yueling" (calendar paintings) was published as preface with no page number.

3)见参考文献[2],再版后为参考文献[5]/See Reference [2], it is reprinted in Reference [5].

Building for the Everyday, a Reflexive Project: Reading Yung Ho Chang

ZHU Jianfei Translated by HUANG Huaqing

Reviewing essays written by Chang from the early 1980s to 2016, this paper argues that there was a breakthrough and a formulation of key ideas on design practice in Chang in the late 1990s. This paper further argues that the intellectual framework Chang adopts is humanistic,Reflexive and critical, something much needed in China, for architecture and beyond.

Yung Ho Chang, basic architecture, material,building and construction, the late 1990s, a new vernacular

墨尔本大学/University of Melbourne

2017-09-12