南海仲裁案中菲律宾主张“单岛定性”问题探析

2017-08-10韩雨潇

韩雨潇

南海仲裁案中菲律宾主张“单岛定性”问题探析

韩雨潇*

在南海岛礁争端中,菲律宾是侵占中国南海岛礁较多的国家,其一直声称对中国南海的部分岛礁拥有主权,菲律宾为了谋求本国在南海的利益,一方面就南海部分岛礁单方面提起仲裁,主张中国的“断续线”违反《联合国海洋法公约》,要求就其海洋权利做出裁定,把中国南海诸岛的主权和海洋权利割裂开来;另一方面,菲律宾企图将中国南海的部分岛礁进行“单岛定性”,尤其是对处于中国实际控制的岛礁进行定性,通过“矮化”中国相关岛屿的性质,以达到损害中国海洋权益的目的。针对菲律宾将中国南海诸岛进行碎片化处理的恶意企图,中国应尽快在南海地区构建远洋群岛制度,从而更好地维护中国的岛屿主权与海洋权益。

南海仲裁案 领土争端 远洋群岛 《联合国海洋法公约》

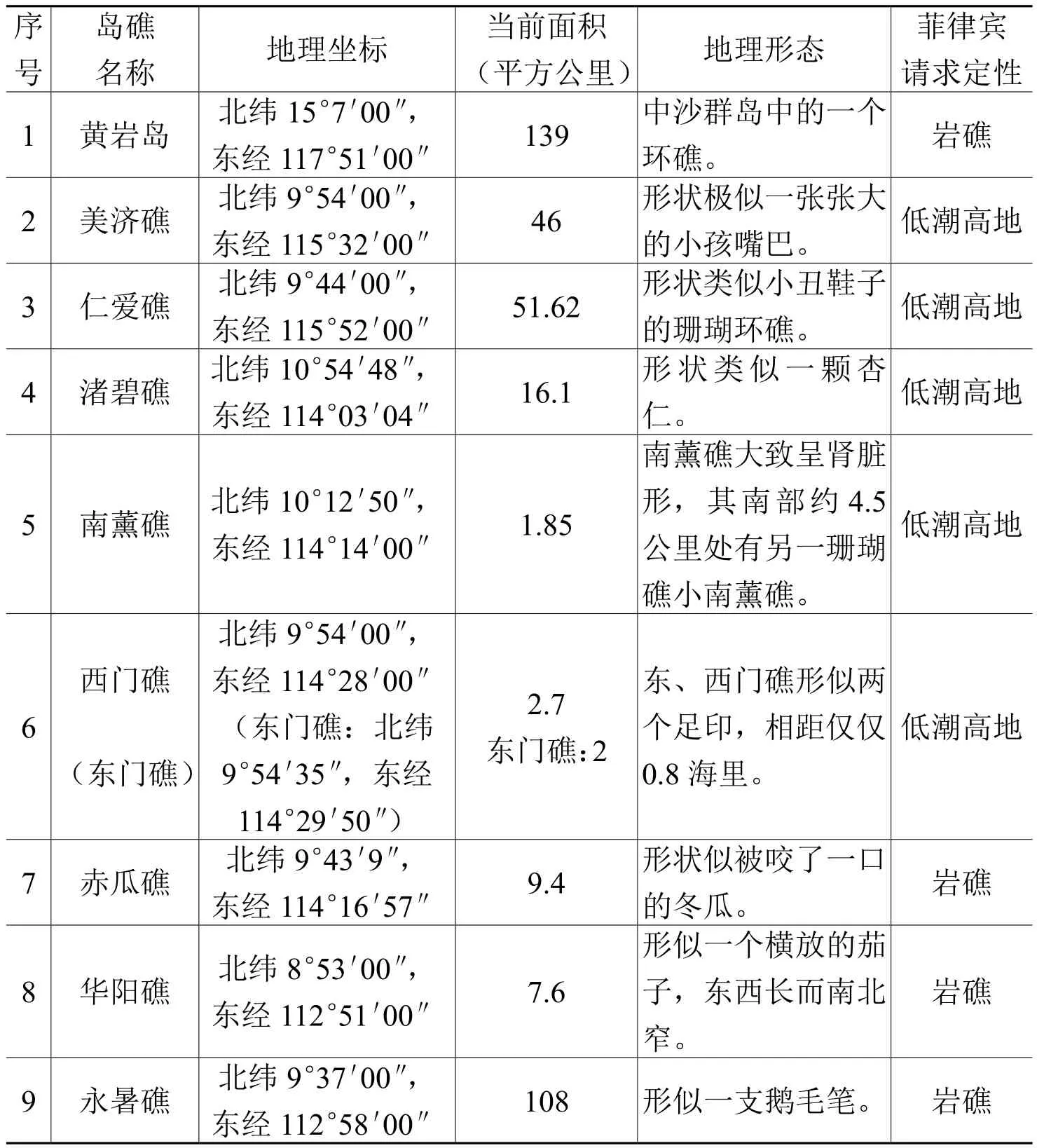

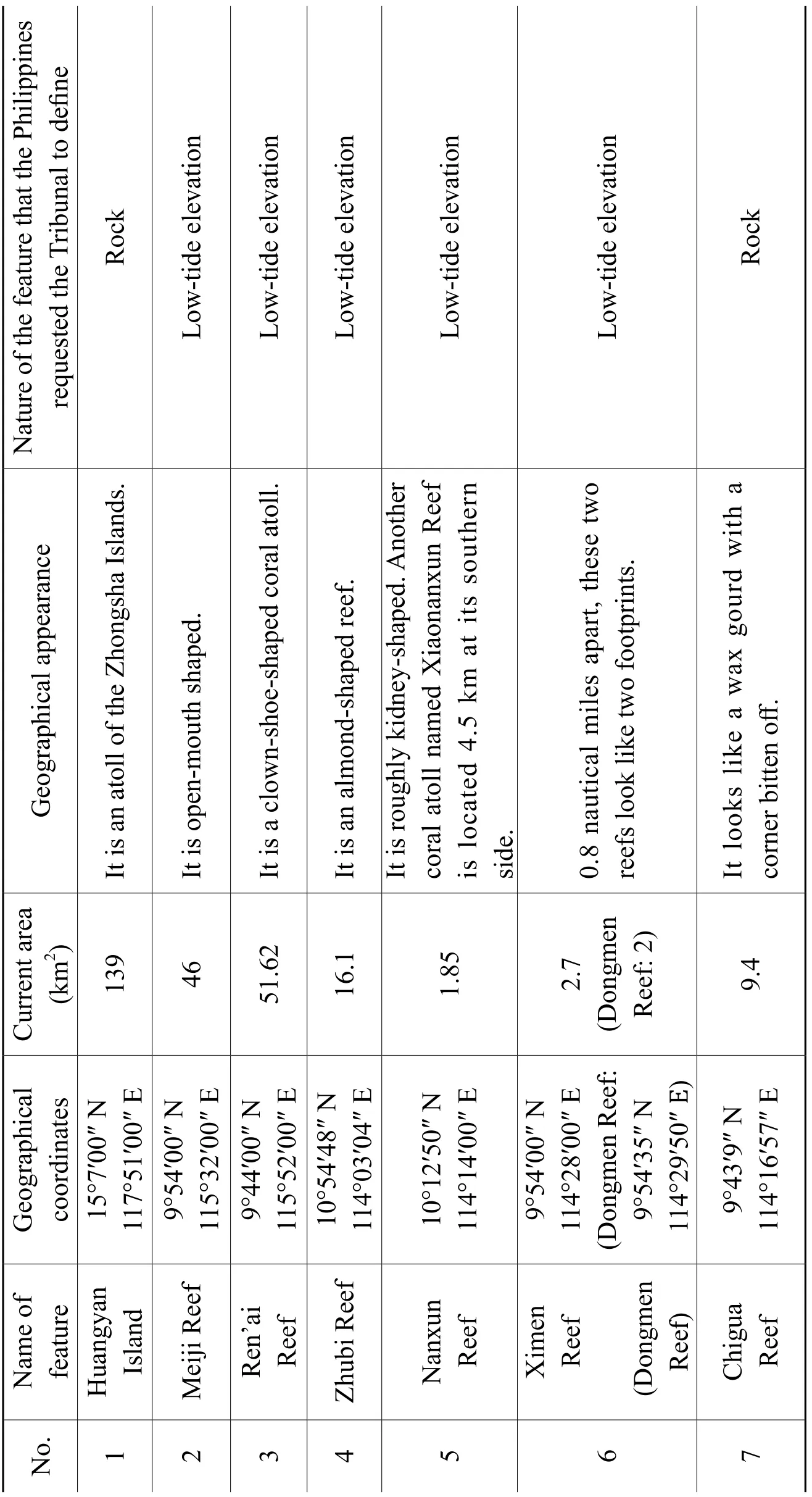

在中国对南海诸岛及其附近海域进行开发利用的历史过程中,从没有任何一个国家对中国南海诸岛的主权、管辖权提出过挑战,无论从历史上还是从法理上来说,中国对南海诸岛及其附近海域均具有不可争辩的主权。菲律宾虽宣称对中国南海诸岛的部分岛屿拥有主权及主权权利,但是20世纪中期以前,没有任何法律文件或者官方领导人讲话表明菲律宾的领土范围包括中国的南海诸岛。20世纪中期开始,随着南海丰富的油气资源、生物资源、空间资源、旅游资源等被不断发现,极大提升了南海的战略与军事价值,加之《联合国海洋法公约》(以下简称“《公约》”)在1994年的生效、亚太格局的变化,促使菲律宾对南沙群岛产生了浓厚的兴趣。自20世纪70年代以来,菲律宾陆续派兵对南沙群岛进行武力侵占,先后非法占据了中国南沙群岛的9个岛礁(见表1)。

2013年1月22日,菲律宾不顾中方的强烈反对,就中菲南海争端单方面提起强制仲裁程序,质疑中国在南海海域所主张的权利的正当性。菲律宾在南海仲裁案中对南海部分岛礁提出“单岛定性”的主张,其根本目的就是企图将南海诸岛肢解开来,使中国无法从整体上维护南海地区的领土主权和海洋权益。2016年7月12日,仲裁庭对南海仲裁案做出“最终裁决”,否定了中国在“断续线”内南海海域的主权权利、管辖权及历史性权利。仲裁庭在审议岛礁的地位时,认定《公约》并未规定如南沙群岛的一系列岛屿可以作为一个整体共同产生海洋区域。①Eleventh Press Release, The South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of the Philippines v. The People’s Republic of China), p. 10, at https://pca-cpa.org/wp-content/uploads/ sites/175/2016/07/PH-CN-20160712-Press-Release-No-11-English.pdf, 21 March 2017.面对菲律宾咄咄逼人的进攻态势,中国有必要从法理的角度对南沙群岛的群岛地位进行探讨并构建群岛制度,从而有力地回击菲律宾碎片化南沙群岛的恶意企图。

表1 菲律宾非法侵占的中国南沙岛礁

一、驳斥菲律宾在南海仲裁案中对南海部分岛礁“切割”的主张

(一)菲律宾企图以《公约》为法律依据,割裂南沙岛礁主权与海洋权利之间的关系,进而全盘否定中国在南海的主权

2016年7月12日仲裁庭发布了南海仲裁案的仲裁裁决。菲律宾在仲裁过程中一共提出了15项诉求,其中第2项诉求是针对中国南海的“断续线”,菲律宾认为中国以南海“断续线”为依据主张海洋权利,这种做法不符合《公约》的规定,仲裁庭应认定是无效的,试图从根本上否定中国在南海地区的所有权利。菲律宾这种诉求十分荒谬,因为其申请仲裁的实体问题不属于《公约》规制的范围,因此《公约》并不能作为处理中菲南海争端的法律依据。①Eleventh Press Release, The South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of the Philippines v. The People’s Republic of China), p. 6, at https://pca-cpa.org/wp-content/uploads/ sites/175/2016/07/PH-CN-20160712-Press-Release-No-11-English.pdf, 21 March 2017.《公约》序言指出:“在妥为顾及所有国家主权的情形下,为海洋建立一种法律秩序……本公约未予规定的事项,应继续以一般国际法的规则和原则为准据。”也就是说,由于《公约》并没有对领土主权争端进行规定,所以岛屿争端的解决应适用一般国际法的规则。《奥本海国际法》认为:“习惯是国际法以及一般法律的最古老和原始的渊源”,而“法律不溯及既往”早已成为习惯法并获得国际社会公认。根据一般国际法,当《公约》与习惯法发生抵触时,习惯法将优于《公约》。②郑海麟:《南海仲裁案的国际法分析》,载于《太平洋学报》2016年第8期,第4页。依据“法律不溯及既往”,中国“断续线”的划定比《公约》生效要早47年,不能用现行法律去约束和指导过去的行为,而中国对于南沙群岛的主权及其附近水域的历史性权利是有着充分的历史和法理依据来佐证的,并且也得到了国际社会的广泛承认,同时,“断续线”的划定并不属于《公约》的管辖范围,其本身是历史问题,所以菲律宾认为中国的“断续线”违反《公约》的诉求并不成立。

菲律宾2013年1月22日向中国发出了《关于西菲律宾海的通知和主张声明》(以下简称“《声明》”),其中第五部分阐述了菲律宾请求仲裁庭予以裁决的13项诉求,其中第10~13项诉求是针对南海海域权利的,请求仲裁庭认定菲律宾在南海相关海域享有专属经济区和大陆架的权利。③Notif i cation and Statement of Claim on West Philippine Sea, pp. 17~19, at http://www.dfa. gov.ph/images/UNCLOS/Notification%20and%20Statement%20of%20Claim%20on%20 West%20Philippine%20Sea.pdf, 22 March 2017.南海相关海域的专属经济区和大陆架权利是从领土主权派生而来的,菲律宾这种割裂南沙群岛主权与海洋权利之间的关系,直接要求仲裁庭对海洋权益进行仲裁的诉求也是不符合国际法中“陆地支配海洋”的原则。国际法院早在1969年北海大陆架案的判决中就明确指出,“陆地支配海洋”是国际法的一项基本原则,陆地是一个国家对其领土向海洋延伸的部分行使权力的法律渊源,也就是说拥有岛屿或者陆地主权才是一个国家拥有该陆地或岛屿附近海域主权权利和海洋权益的基础。④国家海洋局政策研究室编:《国际海域划界条约集》,北京:海洋出版社1989年,第79页。按照传统国际法对国家领土取得方式的认定,只有先占、割让、征服及添附这几种方式,⑤杜蘅之:《国际法大纲(上册)》,台北:台湾商务印书馆1971年版,第216~217页。并没有通过取得大陆架或专属经济区来确定岛屿归属的方式。所以,菲律宾没有拥有南沙群岛的主权却要求仲裁庭对南海相关海域的权利进行仲裁的诉求是十分荒谬的。

(二)菲律宾主张只有群岛国才可适用“群岛原则”,以割裂式的思维认定南海部分岛礁属于不符合《公约》岛屿定义的岩礁、礁石,不可拥有专属经济区、毗连区甚至是领海

根据《公约》第四部分对群岛国制度的规定,群岛原则即群岛国可以依据其在群岛中确定的领海基点划定直线群岛基线,其领海、毗连区、专属经济区、大陆架的宽度应从群岛基线量起,群岛基线所包围的水域为群岛水域,群岛国主权及于群岛水域,但是其他国家在尊重群岛国主权的前提下,在该水域也享有无害通过权、传统捕鱼权等权利。①《联合国海洋法公约》,下载于http://www.un.org/zh/law/sea/los/index.shtml,2017年3月22日。菲律宾属于以群岛为基本领土的国家,海洋资源的开发和利用决定了其国家未来的发展,出于其本国利益考量,菲律宾曾经联合印度尼西亚在1958年前后就主张建立一个专门适用于群岛国家的组合制度。随后菲律宾于1961年6月17日颁布《关于确定菲律宾领海基线的法案》,声称菲律宾群岛周围、各岛之间和连接各岛的全部水域,不论其宽度和面积如何,始终被视为菲律宾陆地领土的附属物,构成菲律宾内陆和内水水域的一部分。②海洋国际问题研究会编:《中国海洋邻国海洋法规和协定选编》,北京:海洋出版社1984年,第60页。也就是说菲律宾是以群岛为中心划定其领海,并用80段直线基线划定了菲律宾的领海基线。所以说,菲律宾是在国际海洋法实践中第一个提出群岛理论概念的国家,而当时的群岛原则还没有得到国际法和国际社会的承认。在1973年第三次联合国海洋法会议筹备委员会会议上,菲律宾、斐济、印度尼西亚、毛里求斯四国首次联合提出群岛原则,但是它们反对将群岛制度扩大适用于大陆国家的远洋群岛,并在随后提出的《群岛条文草案》第1条声称:“该群岛条文草案只适用于群岛国。”③Office for Ocean Af f airs and the Law of the Sea, Archipelagic States – Legislative History of Part IV of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, New York: U.N. Publications, 1990, pp. 7~9.菲律宾等群岛国认为群岛国设立群岛制度可以更好地保护国家安全和经济利益,所以只有群岛国在划定领海或专属经济区时才有适用群岛制度的客观需要。1982年出台的《公约》对群岛国的群岛制度做了专门的规定,但是《公约》并没有明确大陆国家的远洋群岛问题,菲律宾想以《公约》作为大陆国家不适用群岛制度的法律依据,这显然是不合理的,因为大陆国家的远洋群岛问题属于《公约》中的法律空白,而法律未规定事项并不能当然认为是法律禁止事项,大陆国家适用群岛原则也不当然构成违背《公约》义务或者滥用权利,更不是违反一般国际法规则或者原则,所以群岛国基于政治、经济安全等理由主张群岛原则,大陆国家远洋群岛和群岛国的群岛在地理上并无差别,大陆国家也可以基于政治、经济、安全等理由对其远洋群岛适用群岛原则。

由于南海地区地形复杂,大量岩礁难以定性为《公约》范畴内的岛屿,而根据《公约》第121条第3款的规定,不符合《公约》岛屿定义的岩礁是不能依据其主张专属经济区和大陆架的,但在群岛制度体系之下,可以将群岛内的各个岩礁、岛屿作为一个整体,以群岛整体为依据主张主权权利,作为一个整体的群岛是由岛屿及其周围的岩礁共同组成,同时,在群岛制度下群岛基线的运用也将更多的水域划入群岛水域。菲律宾在仲裁申请中对南海部分岛礁的法律性质及法律地位进行分别认定,反对大陆国家适用群岛制度,其根本目的就是想从岛礁的性质入手,割裂一个完整的南沙群岛,企图在南海地区人为地制造一些主权真空地带,损害中国领土主权的完整性。其实菲律宾早已经把南海地区的岛礁视为群岛,其在1978年6月11日发布的第1596号总统令和7月15日颁布的第1599号总统令中,将南沙群岛的33个岛礁、沙洲宣布为菲律宾领土,非法划归巴拉望省的一个独立自治区,把这个范围内的岛群命名为“卡拉延群岛”,2009年3月10日,菲律宾又通过了“第9522号共和国法案”即“领海基线法”,为所谓的“卡拉延群岛”与其他岛屿划定了领海基线。①郭渊:《地缘政治与南海争端》,北京:中国社会科学出版社2011年,第273~281页。同时,针对菲律宾的诉求,仲裁庭其实也注意到菲律宾选取中国南沙部分岛礁定性的行为是不合理的:“由于菲律宾的主张建立在中菲之间不存在专属经济区或大陆架的海洋权利的重叠上,仲裁庭认为应分析中国所主张的所有南海岛礁的海洋权益,不管这些岛礁是否目前由中国占领。”②The Republic of the Philippines v. The People’s Republic of China, Award, 12 July 2016, para. 154, at https://pca-cpa.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/175/2016/07/PH-CN-20160712-Award.pdf, 24 March 2017.

(三)菲律宾通过对南海岛礁性质进行分别认定来主张其所谓的“南海权益”,实际上想避开中菲双方关于《公约》排除声明的适用

2006年8月25日,中国根据《公约》第298条的规定向联合国秘书长提交声明,排除强制仲裁程序适用于海洋划界、历史性权利等海洋争端。③中国根据《联合国海洋法公约》第298条提交排除性声明,下载于http://wcm.fmprc. gov.cn/pub/chn/gxh/zlb/tyfg/t270754.htm,2017年3月24日。菲律宾不顾中国政府对于《公约》的排除性声明申请强制仲裁。根据南海仲裁案的裁决书,菲律宾的第1~2项仲裁请求是诉请仲裁庭裁定中国的“断续线”因违背《公约》的规定而不具备法律效力,从而否定中国在南海的主权及相关权利;第3~7项请求涉及黄岩岛、美济礁、仁爱礁、渚碧礁、西门礁、南薰礁等岛礁的法律地位认定问题,①The South China Sea Arbitration, p. 5, at https://pca-cpa.org/wp-content/uploads/ sites/175/2016/07/PH-CN-20160712-Press-Release-No-11-English.pdf, 21 March 2017.这些仲裁请求表面上是菲律宾主张对其所谓“南海权利”的维护,实际上是针对海域划界和岛礁归属的问题。菲律宾也曾经针对《公约》提出过排除性声明,其于1982年12月10日公布的《菲律宾对于签署1982年〈联合国海洋法公约〉的宣言》第4条声明:“该种签署不应该侵害或损害菲律宾运用其主权权力于其领土之主权,例如卡拉延群岛及其附属之海域。”②吴士存主编:《南海问题文献汇编》,海口:海南出版社2001年,第234页。显然,菲律宾想要以“通过对南海部分岛礁的性质认定来维护其在南海的合法权利”为幌子,证明其提起仲裁只是为了解决与中国在南海问题上的纠纷,不属于超越仲裁庭审理范围的领土主权争端,这不仅是为了避开中国提出的排除性声明,也是为了绕过菲律宾曾经针对《公约》提出的排除性声明。

二、中国态度:中国南沙群岛是不可分割的群岛

(一)仲裁庭对相关岛礁的定性不能否定南海诸岛的整体性

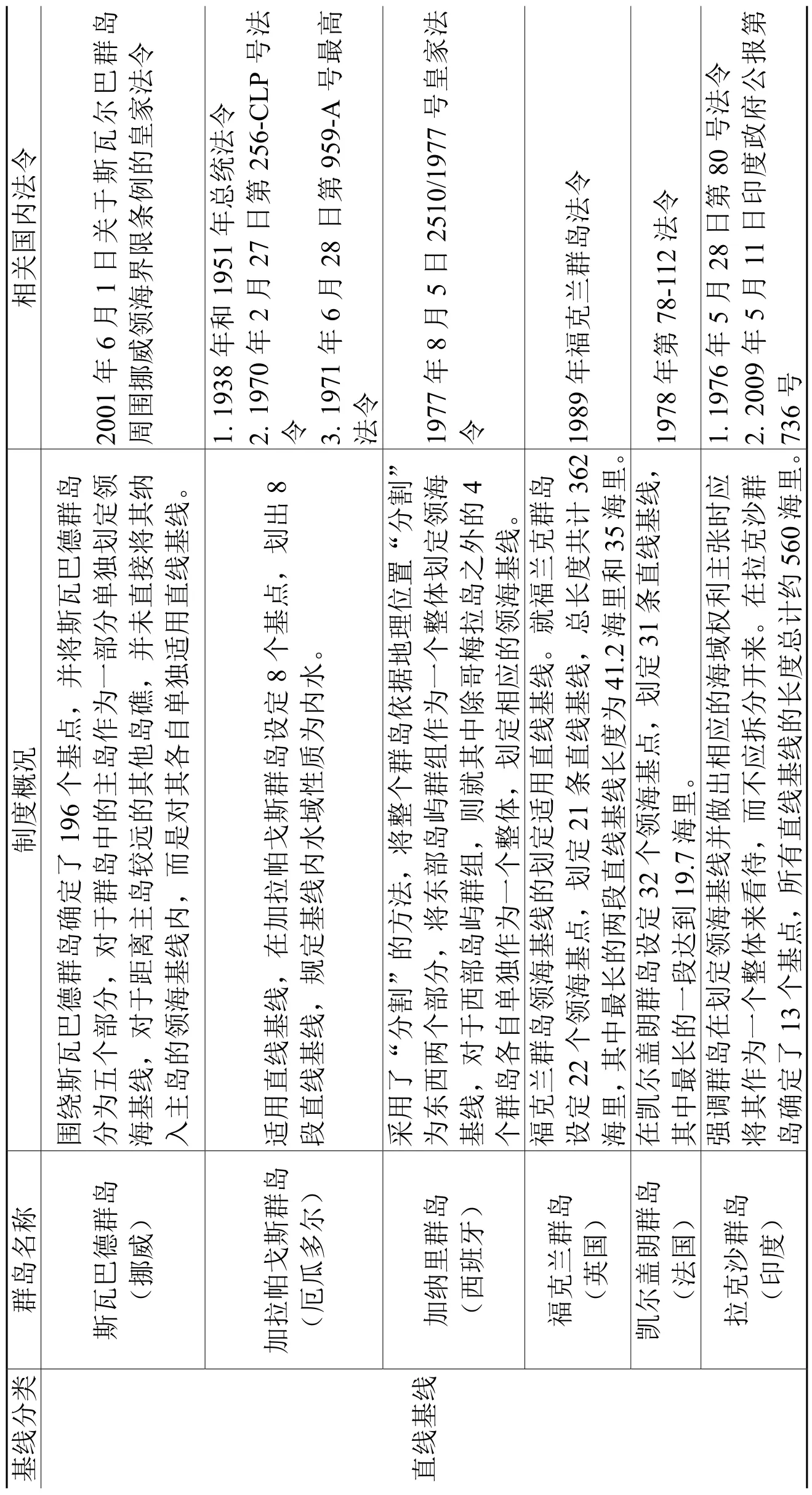

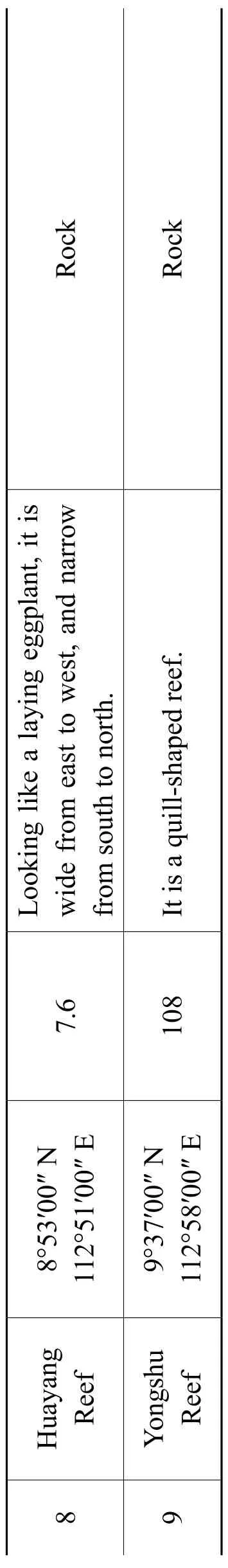

菲律宾在南海仲裁案中提出了对黄岩岛、美济礁、仁爱礁、渚碧礁、南薰礁、西门礁、赤瓜礁、华阳礁分别进行定性的诉求,根据其诉求可以看出菲律宾对相关岛礁性质所持的态度(见表2)。菲律宾认为判定属于“低潮高地”的岛礁不可以享有领海、专属经济区和大陆架,并且不能通过占领或者其他方式取得主权,属于“岩礁”的岛礁不可以享有专属经济区和大陆架,菲律宾企图用化整为零的方式来否定南海诸岛的整体性,从而否定中国在南海诸岛及其附近海域的主权与管辖权。根据《公约》第13条的规定,因低潮高地在涨潮期间会淹没在水中,不能与岛屿一样拥有领海、专属经济区以及大陆架,也就是说,《公约》既没有条文明确规定低潮高地不是领土,也没有规定不能通过先占取得低潮高地的主权,只是规定低潮高地本身所能产生的海洋权利与岛屿有所区别,所以即使相关岛礁被判定为“低潮高地”,也不意味着中国丧失了该岛礁的领土主权。就岩礁而言,根据《公约》第121条第3款规定,岩礁应该属于一种特殊的岛屿,由于其不能维持人类居住或其本身的经济生活,所以不能享有专属经济区和大陆架,但是却可以享有领海。③《联合国海洋法公约》,下载于http://www.un.org/zh/law/sea/los/index.shtml,2017年3月22日。可见,《公约》并没有给“岩礁”下具体定义,有关“维持人类居住或其本身的经济生活”的条件也没有明确的规定,所以菲律宾诉求中的赤瓜礁、华阳礁的性质无法依据《公约》纳入“岩礁”。

《公约》第46条规定了对群岛的要求,即在本质上构成一个地理、经济和政治的实体,或在历史上已经被视为这种实体。从历史角度看,早在东汉时期杨孚《异物志》中记载的“涨海”就是中国古代对包括南海诸岛在内的南中国海的称谓;到了宋代,对南沙群岛、西沙群岛采用了更加形象的称呼,“长沙”、“千里长沙”、“万里长沙”一般指的是西沙群岛,“石塘”、“千里石塘”、“万里石塘”一般指的是南沙群岛。其后中国的历代文献及官方资料对西沙群岛、南沙群岛也均有记载,如明清广东的地方志把“千里长沙”、“万里石塘”列在疆域范围之内。①袁古洁:《国际海洋划界的理论与实践》,北京:法律出版社2001年,第224~225页。从中国古代文献记载中不难发现,中国历史上一直把南海诸岛视为一个整体,所以给南海诸岛如西沙群岛、南沙群岛等整体命名。

从地理、政治和经济角度上看,南海是一个半封闭型的边缘海,海内分布着200多个岛礁,根据它们与海平面的高度差可分为岛屿、沙洲、礁、暗沙和暗滩5种类型,其中露出海面的很少,大部分都是淹没在水下,南海诸岛就是这些岛、洲、沙、滩、礁的总称。南海海底为中国盆地,盆地的边缘与四周陆地间,才有狭宽不一的大陆礁层,也就是说,南海诸岛为一个独立的地理单元,西沙、中沙、南沙和东沙群岛各自又构成了一个独立的区域,形成了各自的大陆架区,所以菲律宾诉求中主要涉及的南沙群岛可以说在地理上是自成一体的。②郭渊:《地缘政治与南海争端》,北京:中国社会科学出版社2011年,第301~302页。中国最早开发和经营了南海诸岛,早在明代时,就有中国渔民到南海诸岛去捕捞和开发,渔民祖辈相传留下的航海指南《更路簿》更是具体记载了中国渔民前往西沙和南沙群岛的航程、航向等,证明了中国自明清以来就开发了南海诸岛。20世纪70年代,厦门大学南洋研究所调查组经过实地考察,在南沙群岛的太平、中业、南威等岛屿上发现了明清时代渔民建立的水井、茅屋、石碑等。③韩振华主编:《我国南海诸岛史料汇编》,上海:东方出版社1988年,第519页。中国历代政府从未停止过对南海诸岛行使主权及行政管理,将南海诸岛的长沙、石塘列入中国疆域管辖范围之内,新中国成立之后出版的地图也都标明南海诸岛属于中国,中国政府也多次发表声明,重申中国对南沙群岛、西沙群岛的主权。1959年中国广东省海南行政区公署在西沙群岛的永兴岛设立西沙、南沙、中沙群岛办事处,履行中国对南海诸岛的行政管辖权,1988年海南省将西沙群岛、南沙群岛、中沙群岛的岛礁及附近海域纳入管辖范围,2012年6月21日,经中国国务院正式批准,撤销三沙办事处,建立地级三沙市,政府驻西沙永兴岛。可见,南海诸岛无论从自然地形上还是从历史上看,都在本质上构成了一个地理、经济和政治的实体。

表2 菲律宾仲裁请求涉及的南海岛礁

(二)国际法依据

1.大陆国家远洋群岛可适用直线基线及历史性权利的法律依据

1935年7月12日挪威发布国王赦令,宣布北纬66°28′48″以北的4海里海域为挪威专属渔区,根据该赦令,在挪威沿岸以及其外缘确定48个领海基点,并把这些基点用直线连接起来划出挪威的领海基线。英国认为挪威采取的直线基线划法违背了国际法,并且此类基线的划定会使一部分公海变为挪威的专属渔区,虽然英挪两国就此进行多次谈判但均未成功,因此英国于1949年向国际法院提起了诉讼。1951年12月18日,国际法院对“英挪渔业案”作出判决:挪威北部海岸地带具有独特的结构且极为曲折,群山环抱中的峡湾和海湾的存在造成海岸线的断续相间,沿岸还包含无数的岛屿、小岛和干礁,形成了一个小岛群(挪威称之为“石垒”),也就说挪威海岸的陆地和海洋之间并没有清晰的分界线,“石垒”的外界构成了其海洋的边界。国际法院认为,领海带必须沿着海岸的一般走向划定,为了测算领海的宽度,国家实践一般采用低潮线,因为这一标准对沿海国最为有利,并且清晰地体现了领海附属于陆地领土的特点。但低潮线不是一成不变的,海岸轮廓的不规则加大了确定适用低潮线的复杂性,所以在海岸线极为曲折的地方,或者近邻海岸有一系列岛屿,在划定包括领海在内的管辖海域时,可适用更实际的方法使领海带的形状更为简明,即采用连结各适当点的直线基线法,所以国际法院认为挪威划定的基线不违反国际法。①Fisheries Case (United Kingdom v. Norway), pp. 127~130, at http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/ fi les/5/1809.pdf, 28 March 2017.

“英挪渔业案”对厘清现有基线划定方法的国际法规则起到了重要作用,案件结束后,挪威这种有别于传统基线划法却又基于特殊地理情形的直线基线法也被各国广泛采纳。第三次联合国海洋法会议的主席阿米拉辛格指出:“在英挪渔业案中国际法院考虑的是直线基线适用于海岸线极为曲折和海岸旁存在群岛的情况,但同时国际法院也指出了领海法的一般原则,即领海带必需沿着海岸线画出,而这对远洋群岛问题的解决能发挥一定的作用。”②C. F. Amerasinghe, The Problem of Archipelagoes in the International Law of the Sea, International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 23, Issue 3, 1974, p. 544.1958年第一次联合国海洋法会议通过的四公约之一《领海及毗连区公约》第4条明确规定了接近海岸的一系列岛屿划定直线基线的方法,“英挪渔业案”的判决可以说是《领海及毗连区公约》确定直线基线法的基础。“英挪渔业案”中国际法院也考量了挪威在该海域的历史性权利问题,认为挪威当地居民百年来完全依赖此地渔业生活形成了历史性权益,挪威的划界方式符合国际法的规定。应当说,该案也可以为中国主张南海断续线内历史性权利提供国际法层面的支持。格林·菲尔德认为,中国破碎的海岸以及众多岛屿的地理特征说明中国有资格适用直线基线,而这似乎也符合“英挪渔业案”所体现的原则。③Jeanette Green Field, China’s Practice in the Law of the Sea, Gloucestershire: Clarendon Press, 1992, p. 72.所以,从法律角度来看,虽然《公约》只规定了“群岛国的群岛制度”,并未规定大陆国家的群岛制度构建,但是国际法院关于“英挪渔业案”的判决及《领海与毗连区公约》第4条为大陆国家远洋群岛采用直线基线提供了法律依据。

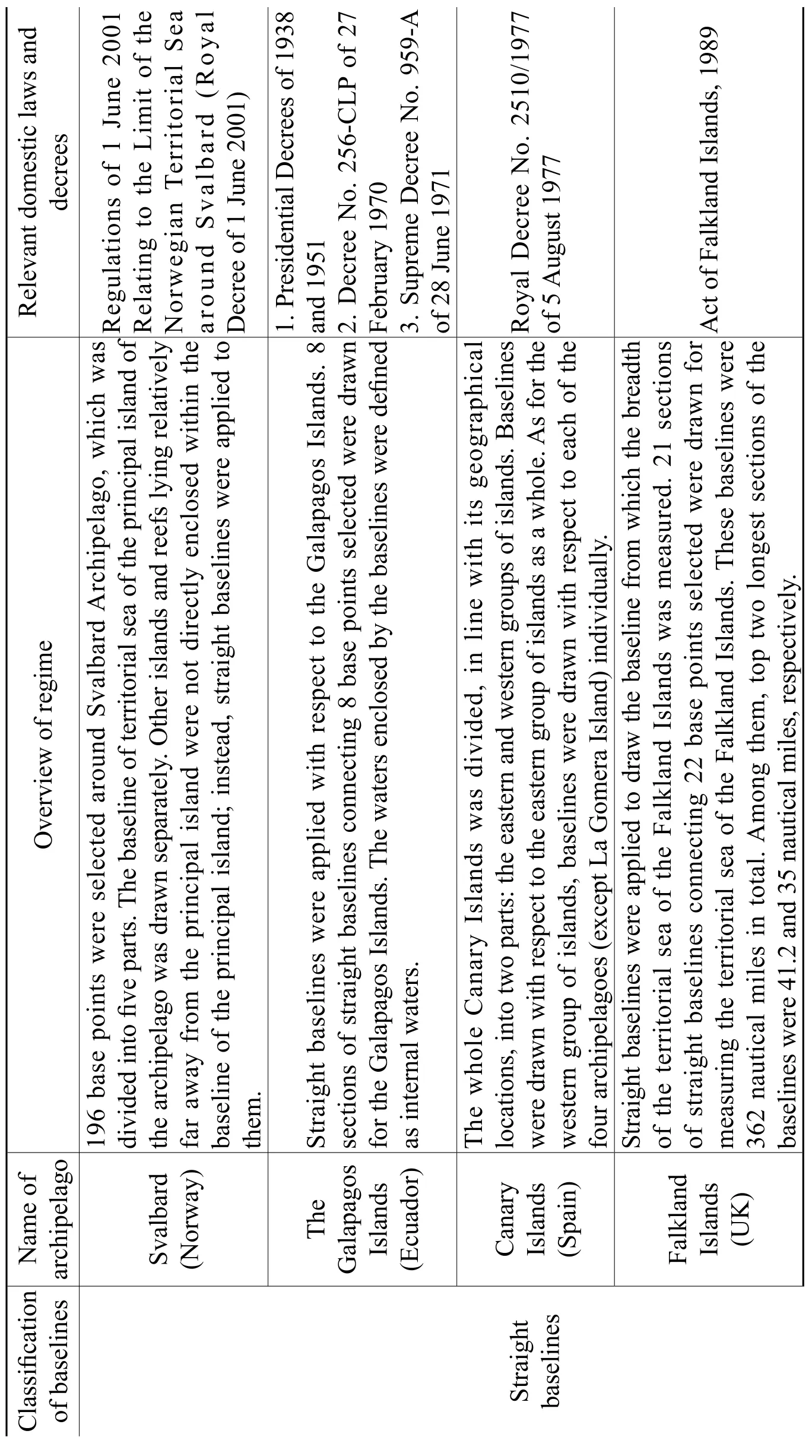

2.大陆国家远洋群岛适用直线基线的他国实践

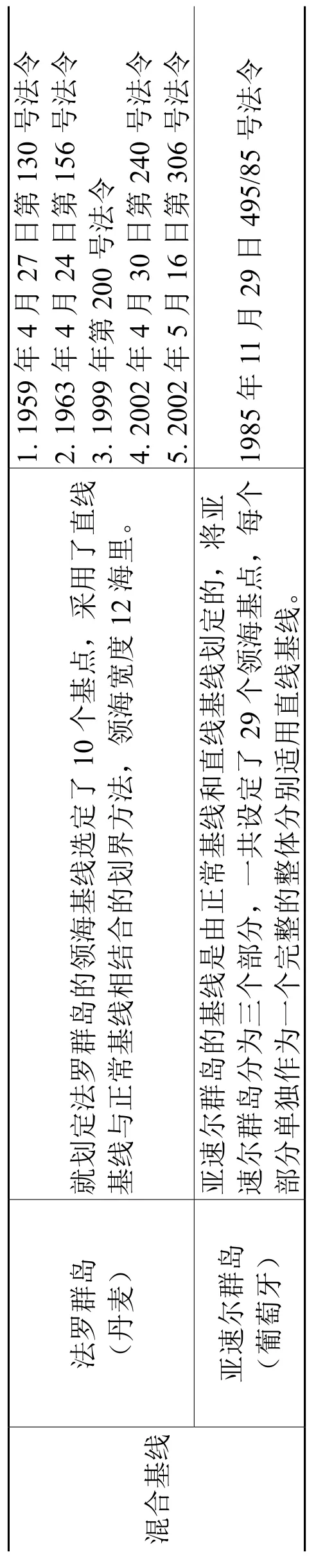

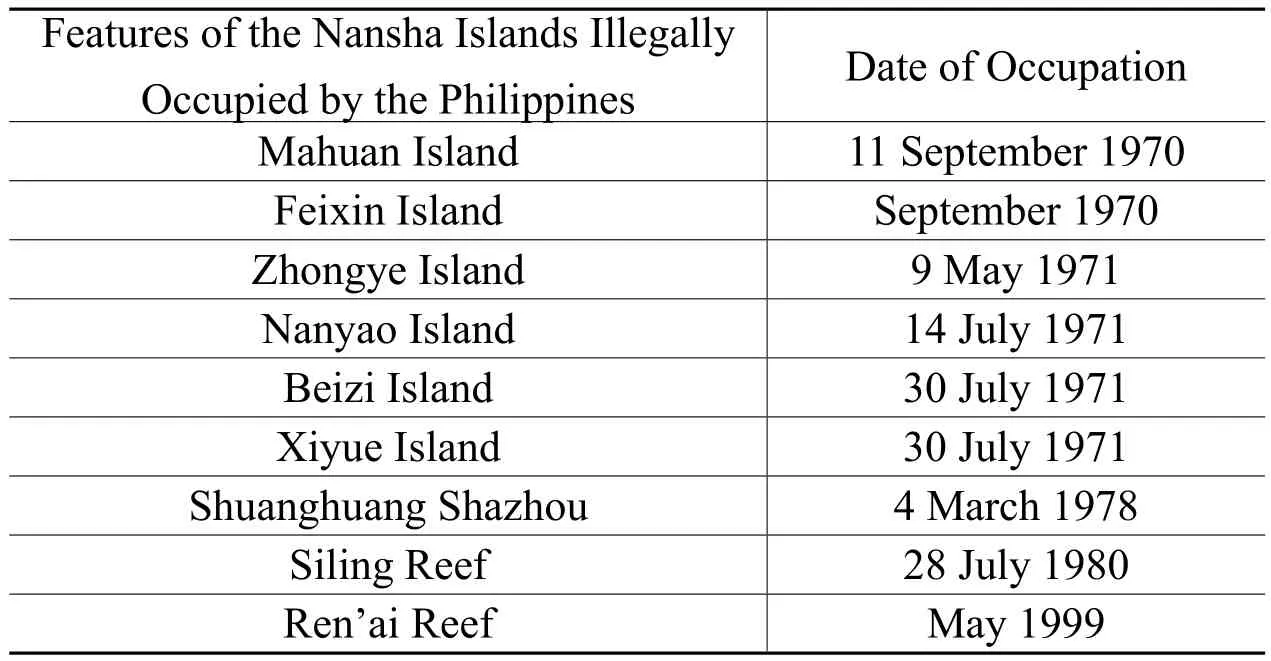

布朗利对国家实践的种类作出了如下列举:外交文书、政策声明、新闻发布、国家立法、国际和国内司法判例、条约和其他国际文件的内容、联合国大会有关

法律问题的决议等。①贾兵兵:《国际公法:和平时期的解释与适用》,北京:清华大学出版社2015年,第32~33页。通过对一些典型国家关于远洋群岛制度方面资料的整理(见表3),发现很多大陆国家在其远洋群岛采用的直线基线在《公约》生效之前就已经存在,还有一部分国家是采用混合基线制度,在《公约》生效之后,仍然维持原有立法或依据《公约》采用新的立法形式确定在远洋群岛适用直线基线,这证明了大陆国家在远洋群岛采用直线基线是稳定的国家实践行为。

表3 典型国家建立群岛制度的实践

混合基线法(罗丹群麦岛)就基划线定与法正罗常群基岛线的相领结海合基的线划选界定方了法10基,用海了里直。线,领个海点宽度采121.1959年年年44月月20030162724日日第第令第第130号号法法令令2.1963 156 3.1999第45号法4.2002 年年月月日日240号号法法令令5.2002 306亚(速葡尔萄群牙岛)亚速部速尔分尔群单群岛独岛分作的为为基三一线个个是部完由分整正,的常一整基共体线设分和定别直了适线29基个线领划海定基的点,,将每亚个用直线基线。1985年11月29日495/85号法令

很多国家不仅在国内法上明确表示在远洋群岛上适用直线基线,还向联合国秘书长递交了照会。2011年3月9日,厄瓜多尔政府向联合国秘书长递交照会,要求记录和宣传其2010年8月2日颁布的第450号执行法令,该法令附有2010年7月12日部长级协议0081和清楚地显示厄瓜多尔加拉帕戈斯洋中群岛直线基线的海图IOA42。②洪农、李建伟、陈平平:《群岛国概念和南(中国)海——〈联合国海洋法公约〉、国家实践及其启示》,载于《中国海洋法学评论》2013年第1期,第193页。葡萄牙2011年5月向大陆架界限委员会提交了外大陆架提案,其提交的附图明确显示了其实践中混合使用了直线基线和正常基线。印度政府2009年5月11日的政府第736号公报阐述了在拉克沙群岛适用直线基线,同时印度于2010年1月29日向联合国秘书长交存该群岛的领海基点坐标和海图。③M.Z.N.76.2010.LOS of 17 February 2010, at http://www.un.org/Depts/los/LEGISLATION ANDTREATIES/PDFFILES/mzn_s/mzn76ef.pdf, 29 April 2017.

3.中国的国内法规定及在西沙群岛的国家实践

中国在西沙群岛的实践也早于《公约》的存在,所以中国的国家实践并非是援引《公约》第7条作为国际法依据。新中国成立之后,中国政府于1958年公布了《关于领海的声明》,确定中国的领海宽度为12海里,采用直线基线法划定领海,并说明了领海制度适用于台湾及南海诸岛,用政府声明的形式确认了南海诸岛及其水域自古以来就是中国的海洋国土。1973年中国代表团向联合国海底委员会提出的《关于国家管辖范围内海域的工作文件》指出:“岛屿相互距离较近的群岛或列岛,可视为一个整体,划定领海的范围。”④赵理海:《关于南海诸岛的若干法律问题》,载于《法制与社会发展》1995年第4期,第56~57页。1992年中国政府制订了《领海及毗连区法》,在第2条具体列举属于中国的群岛和岛屿,以立法的形式再次重申和确认了南海诸岛为中国的固有领土,为南沙群岛领海基线的确定做了法律上的充分准备。1996年5月15日中国颁布《中国政府关于领海基线的声明》,宣布中国大陆领海的部分基线和西沙群岛的领海基线,在第二部分中标明了西沙群岛的28个领海基点,也就是说,中国将西沙群岛视为统一的整体,用直线基线将西沙群岛的领海基点连接起来,构成西沙群岛的领海基线。

三、在南海地区构建远洋群岛制度的意义

(一)从群岛的整体性角度划界,明晰中国在南海的主权

南海诸岛数量庞大。以存在争议最多的南沙群岛为例,虽然其岛屿众多,但平时露出水面的仅有36个,高潮时露出水面的也只有25个,如果对南沙群岛的单个岛礁进行界定,很难符合《公约》第121条岛屿的标准,还会导致国际社会对该岛礁的法律地位产生质疑,从而使中国在南海的管辖水域受到限缩,也就是说,该岛礁将很难获取专属经济区、大陆架甚至是领海。为南海诸岛中的每个岛礁单独划基线只会使中国在南海地区的领海范围被分割,领海与公海纵横交错在一起,中国在南海地区的主权范围就更加模糊。在南海地区构建远洋群岛制度,就可以从群岛的整体性角度进行划界,把南海地区的岛礁视为若干独立的群岛并确定群岛基点及划定领海基线,不仅可以缓解岛礁性质在主权争议中的尴尬地位,还可以明晰中国在南海的主权范围,其影响和意义极为重大。

(二)有效解决中菲南海争端

中菲南海争端主要就是针对岛礁主权归属及海域划界的争端。菲律宾的领海基线是依据群岛原则划定的,以群岛为中心,把位于群岛外缘岛屿之外,但是在条约界线之内的全部水域称作菲律宾的领海,而所谓的“条约边界线”是指1989年《美西巴黎条约》、1900年《美西华盛顿条约》以及1930年《英美条约》中所提到的全部水域所构成的菲律宾领海的外部界限。菲律宾这种领海基线的划法等于把群岛中各岛屿之间的大片公海海域变成了本国的管辖水域,并把基线内的整个海域变为内水。菲律宾还将群岛基线立法,并从群岛基线划出专属经济区和大陆架,不仅将中国在南沙群岛的33个岛礁、沙洲、沙滩划为菲属岛屿,其专属经济区的外部界线还侵入了中国的传统疆界线。为了维护菲律宾所谓的“南海主权”,菲律宾一方面反对中国这样的大陆国家在其远洋群岛上构建群岛制度,其理由是只有由岛屿组成的国家才能适用群岛制度,并且《公约》没有规定大陆国家可以适用群岛制度。另一方面,菲律宾提出对南海部分岛礁分别进行定性,那么如果南沙群岛中的一些岛礁被界定为岩礁或低潮高地,将会对中菲的海洋划界产生重要影响,中国将无法依据这些岛礁在南海主张专属经济区和大陆架,菲律宾的目的就在于通过否定南海诸岛的整体性,限缩中国在南海的主权范围从而给菲律宾非法占领南海岛礁披上“合法”的外衣。虽然《公约》没有明确规定大陆国家可以划定群岛基线,但是《公约》也没有否定大陆国家可以为其远洋群岛构建群岛制度,大陆国家可以为其远离大陆的群岛划定直线基线,基线内的水域是内水或者是领海,而不是群岛水域。中国也可以采用直线基线的方法围绕南海中的岛群划定群岛基线,在群岛制度之下的岩礁、礁石等与岛屿共同组成了一个群岛,海洋划界时应作为一个整体来看。所以中国可以通过构建远洋群岛制度对南海岛礁行使绝对主权,从而粉碎菲律宾企图侵占中国南海岛礁的阴谋。

(三)冲破美国的岛链封锁

南海的地理位置极端重要,不仅是沟通印度洋和太平洋的重要海上通道,还是连通大洋洲和亚洲大陆的交通要冲。美国制订的“岛链战略”是其亚太战略的重要组成部分,依照亚太地区海上地形特点,又分为第一岛链和第二岛链,目的是为了封锁中俄等国家的海上之路。南海是美国第一岛链的一个重要支点,其与朝鲜半岛相呼应,构成所谓的“新月防线”,从海上构成对中国的围堵封锁,所以南海在美国的“岛链战略”中具有极为重要的位置。南海只要不在中国控制之下,美国就可以依据第一岛链全面封锁中国;反之,“新月防线”将不复存在,美国制订的“岛链战略”将被打破,美国在亚太地区的防线只能被迫退回第二岛链。菲律宾因其综合国力孱弱,为了维护其在南海的所谓“主权”,实现其在南海的战略目标,千方百计的拉拢域外大国介入南海争端。美国则支持菲律宾侵占中国的岛礁,希望通过菲律宾牵制中国,否定中国在南海地区拥有的主权,从而维护其“岛链战略”。此外,亚太地区提供的大部分原料的进口都要通过南海航线进入美国,如果南海的海上贸易通道受到破坏,会使美国的经济发展受到影响,同时还将阻断日本大部分的石油和天然气进口。所以美国多次声称,其在南海地区的利益诉求主要是保持南海国际航道的畅通,而中国政府也在各种场合多次明确表示,中国维护南沙群岛的主权和海洋权益并不会影响外国船舶和飞机根据国际法所享有的航行自由和飞越自由。

在南海构建远洋群岛制度,中国在划定领海基线并主张相应的海域权利时可将群岛作为整体来看待,从而有力回击美菲利用《公约》的空白否定与质疑中国在南海的主权。同时,中国还可以借鉴《公约》的规定,在相关水域设定无害通过权及群岛海道通过权,中国划分出来以供外国船舶自由通行的航运水道必然是由主权国多方综合考量,且能够安全航行的水道,中国对这些水道的管理和维护,也会有利于国际航运的安全,这样既保证了中国在该区域的绝对主权,又可以保障他国船只在该区域的自由航行和安全。可以说,在南海地区构建远洋群岛制度不仅可以维护中国在南海的主权,还可以突破美国对中国的岛链封锁。

(四)推动现行海洋法规则的发展

自1982年《公约》诞生已经走过了30多年,虽然其确立了人类利用和管理内水、领海、毗连区、大陆架、专属经济区等海洋区域的基本法律框架,但是在群岛制度方面的规定却存在诸多缺陷,《公约》规定的群岛制度是妥协的产物,由于一些国家的反对,《公约》在起草过程中搁置了关于大陆国家远洋群岛的争议,许多国际法学者都坦诚指出,《公约》回避大陆国家远洋群岛能否适用群岛制度问题是政治和外交因素影响的结果。①卜凌嘉、黄靖文:《大陆国家在其远洋群岛适用直线基线问题》,载于《中山大学法律评论》2013年第2辑,第110页。随着越来越多的国家已经将直线基线运用于本国的远洋群岛海域划定,《公约》还停留在1982年的共识之上,未能根据国家实践及国际惯例的变化及时调整。菲律宾出于本国的利益,背离《公约》原则与精神,对《公约》进行恶意解释,抓住并利用《公约》的妥协性和滞后性为自己的侵占事实寻找所谓的“国际法依据”,更加激化了南海地区的争端。法律常常以既往的传统为基础逐渐地发生变化,而不是发生根本性的变化。一些价值观念最初也是通过不具有约束力的“软法”得到表达,转而影响公共舆论、政治议程以及填补条约法中的空白。各国显然不会就所有新的海洋问题展开正式谈判,这样《公约》所带有的精心设计的修正②《联合国海洋法公约》第155条和第312~314条,下载于http://www.un.org/zh/law/sea/ los/index.shtml,2017年3月22日。机制就很难得到运用,在这种情况下,通过处理具体海洋问题的全新区域性或全球性条约、国家实践、政府间组织的实践则会推动海洋法新规则的建立。中国把从《公约》群岛国制度引申出来的大陆国家远洋群岛制度用于南海岛礁,并非只关注本国在南海地区的主权和主权权利,而是努力探寻各国在南海地区存在激烈争端的根源,以此为基础提出切实可行的解决方案。中国在远洋群岛制度框架下,在南海地区寻求与各相关国家和平解决争端,合作共赢,积极探索,为推动国际海洋规则的发展作出贡献。

四、针对中菲南海仲裁所涉南沙群岛的群岛制度构建建议

(一)南沙群岛的基线划定

中国在南沙群岛划定基线应该依据大量国家实践的惯常做法,即以直线基线的方法来划定。南沙群岛也满足适用直线基线的条件,原因包括三点:第一,从地理上看,根据国际法院对于“英挪渔业案”的判决,划定直线基线的地理标准为“海岸极为曲折”或者“海岸临近一个群岛”,众多岛礁构成的南沙群岛其轮廓极为曲折,符合国际法院 “海岸极为曲折”的条件;第二,国际法院认为,领海带必须沿着海岸的一般走向划定,由于基线内的海域必须充分接近陆地领土,使其受内水制度支配,中国选择在南沙群岛适用直线基线就是为了尊重海岸、岛屿的自然轮廓,充分考虑南沙群岛的自然地理走向;第三,南海仲裁案中菲律宾提出的“单岛定性”,实际上忽略了我国南沙群岛的整体性,从地理、经济和政治的角度来看,组成南沙群岛的岛、礁、沙、滩以及相连的水域已经在本质上构成一个实体,或在历史上已被视为这种实体。①郑雨晨:《大陆国家的洋中群岛制度的演变及其对我国南海诸岛的影响》(硕士论文),北京:外交学院2016年版,第34页。南沙群岛已被视为一个整体且已经得到了国际法学界和国际社会的认可。目前已公布的远洋群岛的基线划定均遵循了整体性原则,对于这一问题,中国也以立法的形式在《关于国家管辖范围内海域的工作文件》②《关于国家管辖范围内海域的工作文件》第1条第6款:“岛屿相互距离较近的群岛或列岛,可视为一个整体,划定领海范围。”中对群岛的整体性做出了确认,1992年2月25日通过的《中华人民共和国领海及毗连区法》也再次确认采用直线基线法划定南海各群岛的领海基线。

针对直线基线的合理适用问题,若以南沙群岛为整体并连接外缘岛礁适当的基点来划定直线领海基线容易导致基线内海域过大,对周边国家包括航行自由、海洋资源开采等多方面海洋利益产生影响,从而招致他国的非议。由于南沙岛礁众多且情况复杂,虽然将其视为一个整体,但在划定基线时可对整个群岛进行分割,以多个群礁的方式划定基线,并且不将基线内的全部水域都定性成“内水”。

(二)充分做好构建群岛制度的法律准备,顺应海洋权益法制化的潮流

海洋法是平衡各国海洋权益的基础,《公约》规定了各国管理和利用海洋的法律框架。在当前的形势下,各国海洋权益的维护日趋法制化,国家间海洋争端的解决都离不开完备的海洋法制。此外,《公约》也不是一个静态不变的法律体系,需要在实践中不断完善。我国也必须顺应这一潮流,充分利用法律武器来维护自身的海洋权益。《公约》作为一部通过各国协商一致达成的“海洋宪章”,难免有妥协和折中的内容,为了照顾各方面的利益,《公约》中的一些条文规定模棱两可,处于不同立场或利益的国家可以从不同角度进行解释。因此,中国需要加强对《公约》的研究与应用,力求在实施过程中用好用足其法律制度,如对南海断续线法律地位的研究及明确中国的历史性所有权,在法理上找到有力根据,以求和平解决问题。虽然中国的海洋法律体系已经初步建立,但还存在很多问题和不足。比如中国1996年颁布的《中华人民共和国政府关于中华人民共和国领海基线的声明》虽然宣布了大陆领海的部分基线和西沙群岛的领海基线,并提出了中国政府将会再行宣布中华人民共和国其余的领海基线,但是迄今二十年过去了,海阳岛到成山头的基线以及南海其他群岛的基线仍未公布,而很多拥有远洋群岛的大陆国家早在《公约》出台之前就已经颁布实施了相关法律。不难发现,中国的海洋立法存在明显滞后性,而《公约》的贯彻和执行必须依赖国内法制建设,可以说,《公约》的成败与否很大程度上取决于一国的法制建设水平。近年来,无论国内还是国际层面,海洋格局和权益都发生了巨大变化,所以应该针对新情况、新问题,通过国内立法完善和细化《公约》中不明确、不具体、甚至不完善的条款(正如大陆国家的远洋群岛制度),真正建立起完善的海洋法律体系,在开发海洋、利用海洋、维护中国海洋权益方面做到有法可依,才能最大限度地维护中国对南海诸岛的主权。此外,中国还应该积极参与联合国关于海洋方面的国际法规讨论和制定,积极参加国际学术会议,让世界了解中国的立场和观点,让国际海洋法规能够反映中国合理的权益诉求。

(三)新形势下中国对于中菲南海争端的策略思考

菲律宾与中国的南海主权争端一直都比较激烈,近年来在域外大国的支持下,菲律宾在南海问题上不断挑战中国。随着2016年6月30日,杜特尔特当选新一任的菲律宾总统,就任后打破阿基诺三世时期推行的亲美政策,推行“不依赖美国”的独立外交政策,虽然其依然承认南海仲裁的结果,但对通过国际仲裁解决南海问题不抱希望,多次强调不会与中国发生战争,愿意与中国通过合资的方式共同开发南海油气资源,并欢迎中国帮助菲律宾改善基础设施。①Duterte Favors Making Deal with China over Dispute, at http://globalnation.inquirer. net/138487/duterte-favors-making-deal-china-dispute, 31 March 2017.杜特尔特政府虽然不大可能距离美国远一点,但是不难发现其策略转变为如何在不得罪美国的同时与中国修好,从而实现两头通吃,既享受美国提供的安全保障,又搭上中国经济发展的快车。②张洁:《南海博弈:美菲军事同盟与中菲关系的调整》,载于《太平洋学报》2016年第7期,第33页。去年10月杜特尔特总统访问中国期间,中菲两国元首达成了妥善处理南海问题的重要共识,双方重回对话协商妥善处理南海问题的正确轨道。③2017年3月30日外交部发言人陆慷主持例行记者会,http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/ fyrbt_673021/t1450196.shtml,2017年3月30日。《中菲双方联合声明》专门就南海问题进行了详细阐述,并在第40条④《中华人民共和国与菲律宾共和国联合声明》第40条:“双方就涉及南海的问题交换了看法。双方重申争议问题不是中菲双边关系的全部。双方就以适当方式处理南海争议的重要性交换了意见。双方重申维护及促进和平稳定、在南海的航行和飞越自由的重要性,根据包括《联合国宪章》和1982年《联合国海洋法公约》在内公认的国际法原则,不诉诸武力或以武力相威胁,由直接有关的主权国家通过友好磋商和谈判,以和平方式解决领土和管辖权争议。”中明确提出“由直接有关的主权国家通过友好磋商和谈判,以和平方式解决领土和管辖权争议”,这就等于以政府文件的形式进一步固化了双方的官方立场,可以说,中菲关系目前出现了历史性的转圜。但就目前形势来说,由于主权问题中菲分歧较大,短时间内中菲恐怕很难达成协议,但如果要等到争议解决之后才能进行合作,那么合作就永远不会存在,相对而言,“搁置争议,共同开发”作为中菲南海争端的临时解决方法是较为现实可行的,中国也应针对新情况对“搁置争议,共同开发”战略进行新思考。

首先,促进“搁置争议,共同开发”原则的具体化。《南海各方行动宣言》在某种意义上可以说是“搁置争议,共同开发”的体现,但是并不具有法律约束力,缺乏可供操作的具体内容,这样各国就会根据本国的利益需求,产生不同的理解或主张。2016年《中菲双方联合声明》第41条表明:“双方承诺全面、有效落实《南海各方行动宣言》,愿共同努力在协商一致基础上早日达成‘南海各方行为准则’。”①《中华人民共和国与菲律宾共和国联合声明》第41条:“双方回顾了2002年《南海各方行为宣言》和2016年7月25日于老挝万象通过的中国-东盟外长关于全面有效落实《宣言》的声明。双方承诺全面、有效落实《宣言》,愿共同努力在协商一致基础上早日达成‘南海行为准则’。”《南海各方行为准则》是对《南海各方行动宣言》的具体落实,《中菲双方联合声明》充分表明了中菲两国就南海问题坦诚交换意见,并赞同以和平友好协商的方式寻求问题的妥善解决。具体到南沙群岛问题,在搁置岛礁主权争议的前提下,共同开发是在实行划界前的过渡期内,在不损害双方主权立场、法律立场的情况下进行的合作。中菲两国需要以协议的方式共同勘探和开采主权争议区域内的矿产资源,共享开发收益,而在南沙海域没有争议的油气富集地区,中国应当尽快展开勘探开发,建立起钻井平台和采油平台,显示存在,为后续的相关国家实践奠定基础。②薛桂芳:《蓝色的较量——维护我国海洋权益的大博弈》,北京:中国政法大学出版社2015年版,第265页。中国仍然坚持南海诸岛的主权,时刻保持对南海问题的关注和研究,以期在稳定、和谐、互信的良好氛围中,早日和平解决中菲南海争端。

其次,应该努力消除实现“搁置争议,共同开发”的障碍。中菲在南海问题上的信息不对称是实现“搁置争议,共同开发”的最大障碍,彼此互相防范导致在对抗中不断加码,因此双方未能搁置争议,反而争议不断,各自开发。中菲南海争端的解决,需要双方建立和保持畅通的沟通渠道,使各方在南海问题上的信息透明。根据2016年《中菲两国的联合声明》第42条③《中华人民共和国与菲律宾共和国联合声明》第42条:“双方同意继续商谈建立信心措施,提升互信和信心,并承诺在南海采取行动方面保持自我克制,以免使争议复杂化、扩大化和影响和平与稳定。鉴此,在作为其他机制的补充,不损及其他机制基础上,建立一个双边磋商机制是有益的,双方可就涉及南海的各自当前及其他关切进行定期磋商。双方同意探讨在其他领域开展合作。”的规定,中菲之间将建立一个专门针对南海问题定期举行会晤的双边磋商谈判机制,并且双方同意探讨在其他领域开展合作。中菲定期磋商机制的建立,将会增进双方了解相互之间有关南海问题的立场、观点,形成双方积极互动的局面,通过对话缩小分歧,从而减少双方的战略误判。总之,通过对话协商来解决争端,中菲两国的国家利益必定会得到最大限度的实现。

五、结 论

自2012年4月“黄岩岛”事件以来,菲律宾便扬言要将“黄岩岛”事件提交国际海洋法法庭,目的是想使南海争端国际化,借此赢得国际舆论的支持。同时,菲律宾还企图对中国南沙部分岛礁进行“单岛定性”,使中国在南海地区的四大群岛被完全肢解开来,从而否定中国在南海地区的主权与管辖权。由于大陆国家构建远洋群岛法律制度在先例、国家实践、法理基础等方面均有着充分的依据,所以中国应当尽快在南海地区构建远洋群岛法律制度,从而更好地维护中国的海洋权益。

During China’s historically development and exploitation of the islands in the South China Sea (SCS), no States had ever raised any challenges to China’s sovereignty and jurisdiction over these islands. China has, both historically and jurisprudentially, indisputable sovereignty over the SCS Islands and their adjacent sea areas. The Philippines alleged that it had sovereignty and sovereign rights over some islands in the SCS; however, prior to the mid-20th century, no legal instruments or speeches of government leaders contain words telling that the territory of the Philippines includes the SCS Islands of China. The strategic and military significances of the SCS was hugely raised by the gradual discovery of rich oil, gas, living, space, and tourism resources in the SCS since the mid-20th century. Additionally to that, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (hereinafter referred to as the “UNCLOS” or the “Convention”) entered into force in 1994, and the political landscapes of the Asian Pacif i c Region were altered. All these intrigued the Philippines to cast its covetous eyes on the Nansha Islands. Since 1970s, the Philippines successively sent troops to encroach upon the Nansha Islands by force, and illegally occupied nine features of China’s Nansha Islands (see Table 1).

On 22 January 2013, the Philippines, disregarding the strong protests from China, unilaterally initiated a compulsory arbitral procedure against China, which challenged the legitimacy of China’s claims to rights in the SCS waters. In this arbitration, the Philippines requested to def i ne the nature of some islands in the SCS individually, attempting to disintegrate the SCS Islands, and further make China unable to protect its territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests in the SCS region as a whole. On 12 July 2016, the Arbitral Tribunal constituted for the arbitration (hereinafter referred to as “Tribunal”) released the fi nal award, denying China’s sovereign rights, jurisdiction and historic rights within the “dashed-line”in the SCS. When reviewing the status of some islands or rocks, the Tribunal held that the UNCLOS did not provide for a group of islands such as the Nansha Islands to generate maritime zones collectively as a unit.①Eleventh Press Release, The South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of the Philippines v. The People’s Republic of China), p. 10, at https://pca-cpa.org/wp-content/uploads/ sites/175/2016/07/PH-CN-20160712-Press-Release-No-11-English.pdf, 21 March 2017.Facing the Philippines’aggressive attacks, it is necessary for China to discuss, jurisprudentially, the status of the Nansha Islands as a group of islands (archipelago), and establish a regime of archipelago, so as to expose and criticize the Philippines’ malicious intent tofragmentize the Nansha Islands.

Table 1 Features of the Nansha Islands Illegally Occupied by the Philippines

I. Refutation Against the Philippines’ Proposal to“Fragmentize” Some Islands in the SCS Arbitration

A. The Philippines Intended to Cut of f, Using the UNCLOS as a Tool, the Link between the Sovereignty and Maritime Rights of the Nansha Islands, and Further to Totally Vitiate China’s Sovereignty in the SCS

On 12 July 2016, the Tribunal released the fi nal award for the SCS Arbitration. The Philippines raised 15 Submissions in the arbitral procedure. Among them, Submission No. 2 concerns China’s “dashed-line” in the SCS. The Philippines alleged that China’s claims to rights with respect to the maritime areas of the SCS encompassed by the “dashed line” were contrary to the UNCLOS, and therefore requested the Tribunal to decide that such claims were without lawful effect. In doing so, the Philippines attempted to fundamentally deny all of China’s rights in the SCS. This submission is rather absurd, because the essence of the subjectmatter of the arbitration was beyond the scope of the UNCLOS, which cannot beinvoked as the legal basis to settle the disputes between the Philippines and China.①Eleventh Press Release, The South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of the Philippines v. The People’s Republic of China), p. 6, at https://pca-cpa.org/wp-content/uploads/ sites/175/2016/07/PH-CN-20160712-Press-Release-No-11-English.pdf, 21 March 2017.The Preamble of the UNCLOS states: “establish through this Convention, with due regard for the sovereignty of all States, a legal order for the seas and oceans …matters not regulated by this Convention continue to be governed by the rules and principles of general international law.” That is to say, since the UNCLOS contains no provisions concerning the dispute over territorial sovereignty, the settlement of disputes over islands should be governed by the rules of general international law. Oppenheim’s International Law notes, “Custom is the oldest and the original source of international law as well as of law in general.” And “lex prospicit non respicit”has become a rule of customary law for a long time, and was widely acknowledged in the international community. In accordance with general international law, the customary law will have a supremacy over the UNCLOS, if the two are in conf l ict.②ZHENG Hailin, International Law Analysis of the South China Sea Arbitration Case, Pacif i c Journal, Vol. 24, No. 8, 2016, p. 4. (in Chinese)The “dashed-line” was drawn 47 years earlier than the entry into force of UNCLOS. In line with the rule “lex prospicit non respicit”, current laws cannot be applied to govern and regulate previous conducts. China’s sovereignty over the Nansha Islands and historic rights to their adjacent waters are based on sufficient historical and jurisprudential evidences, which have also been widely recognized by the international community. Apart from that, the drawing of the “dashed-line”is not governed by the UNCLOS; it is a historical issue. Therefore, the Philippines’claim that China’s “dashed line” was contrary to the Convention is not founded in law and fact.

Part V of the Notification and Statement of Claim of the Republic of the Philippines (hereinafter referred to as “Statement of Claim”) issued by the Philippines to China on 22 January 2013, articulated 13 Submissions that the Philippines requested the Tribunal to adjudicate. Submissions No. 10~13 concern the rights to the SCS waters, requesting the Tribunal to determine the Philippines’entitlements to exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and continental shelf in the relevant waters of the SCS.③Notif i cation and Statement of Claim on West Philippine Sea, pp. 17~19, at http://www.dfa. gov.ph/images/UNCLOS/Notification%20and%20Statement%20of%20Claim%20on%20 West%20Philippine%20Sea.pdf, 22 March 2017.The entitlements to EEZ and continental shelf in the relevant waters of the SCS are derived from territorial sovereignty. However, thePhilippines, through cutting off the link between the sovereignty and maritime rights of the Nansha Islands, directly asked the Tribunal to rule on its maritime entitlements. This request is inconsistent with the rule of “the land dominates the sea” on international law. In the judgment of the North Sea Continental Shelf Case, 1969, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) explicitly pointed out that, “the land dominates the sea” was a basic rule of international law, and the land was the legal source of the power which a State may exercise over territorial extensions to seaward. In other words, the sovereignty over an island or land is the basis for a State to enjoy the sovereign rights and maritime entitlements to waters at the vicinity of the island or land.①Policy Research Office of State Oceanic Administration, Collection of International Maritime Delimitation Treaties, Beijing: China Ocean Press, 1989, p. 79. (in Chinese)Traditional international law asserts several modes of acquiring territory as, occupation, cession, conquest, and accretion.②DU Hengzhi, An Outline of International Law (I), Taipei: The Commercial Press, Ltd., 1971, pp. 216~217. (in Chinese)However, the ownership of an island cannot be obtained by acquisition of continental shelf or EEZ. Therefore, the request of the Philippines, which lacked the sovereignty over the Nansha Islands, to Tribunal to adjudicate on its rights to the relevant waters of SCS is ridiculous.

B. The Philippines Alleged That the Archipelagic Doctrine Was Merely Applicable to Archipelagic States, and That Some Islands in the SCS Were Not Qualif i ed as Islands under the UNCLOS, but “Rocks”or “Reefs” That Did Not Generate EEZ, Contiguous Zone, or Even Territorial Sea

In accordance with the UNCLOS Part IV (Archipelagic States), an archipelagic State may draw straight archipelagic baselines based on the territorial sea base points of the archipelago. The breadth of its territorial sea, contiguous zone, EEZ and continental shelf shall be measured from archipelagic baselines. The sovereignty of an archipelagic State extends to the waters enclosed by the archipelagic baselines, described as archipelagic waters, where other States enjoy, among others, right of innocent passage and traditional fishing rights, upon the precondition that the sovereignty of the archipelagic State is respected.③UNCLOS, at http://www.un.org/zh/law/sea/los/index.shtml, 22 March 2017.The Philippines is a country whose territory mainly consists of islands. The exploration and exploitationof marine resources is critical to the future development of the whole country. Considering its own state interests, the Philippines, together with Indonesia, proposed around 1958 to establish a combined regime specially for archipelagic States. It promulgated An Act to Def i ne the Baselines of the Territorial Sea of the Philippines (1961 Republic Act No. 3046) on 17 June 1961, which states that all the waters around, between and connecting the various islands of the Philippine archipelago, irrespective of their width or dimension, have always been considered as necessary appurtenances of the land territory, forming part of the inland or internal waters of the Philippines.①Institute of International Oceanic Studies, Selection of Marine Laws, Regulations and Agreements of China’s Marine Neighbors, Beijing: China Ocean Press, 1984, p. 60. (in Chinese)That is to say, the Philippines delineated its territorial sea by using the Philippine archipelago as the center, and used 80 sections of straight baselines to draw the baseline from which the Philippine territorial sea was measured. In this sense, the Philippines is the fi rst State which raised the theoretical concept of archipelago. At that time, the archipelagic doctrine has not been acknowledged by the international law or community. At one session of the Preparatory Committee for the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (1973), four States – the Philippines, Fiji, Indonesia, Mauritius – jointly put forward the archipelagic doctrine, but they all objected to extending the application of the archipelago regime to the mid-ocean archipelagoes of continental States. Article 1 of the Draft Articles on Archipelago, which was proposed by them later, also stated that this Draft only applied to archipelagic States.②Office for Ocean Af f airs and the Law of the Sea, Archipelagic States – Legislative History of Part IV of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, New York: U.N. Publications, 1990, pp. 7~9.The Philippines and other archipelagic States held that the establishment of a regime for archipelagos would better protect their national security and economic interests, therefore, only archipelagic States have the objective need to apply the archipelago regime when drawing their territorial sea or EEZ. The UNCLOS of 1982 contains special provisions regarding the archipelago regime of archipelagic States, however, it did not expressly address the issue concerning the mid-ocean archipelagoes of continental States. It is, obviously, unreasonable for the Philippines to invoke the UNCLOS as the legal basis to support its claim that the archipelago regime did not apply to continental States. The reasons are listed as follows: fi rstly, the issue concerning the mid-ocean archipelagoes of continental States is a legal vacuum leftby the UNCLOS, and the matters uncovered in the law should not be considered as the matters prohibited by law; secondly, a continental State’s application of the archipelagic doctrine does not necessarily amount to a breach of the obligations or an abuse of rights under the UNCLOS, not to say a violation of the rules or principles of general international law. Since, geographically, the mid-ocean islands of continental States are no different from the islands of archipelagic States, the continental States may also, for political, economic and security concerns, require to apply the archipelagic doctrine to its mid-ocean islands, just like the archipelagic States.

Due to the complex topography of the SCS region, a great number of rocks are difficult to be defined as islands under the UNCLOS. As per Article 121(3), rocks disqualif i ed as islands under UNCLOS are not entitled to EEZ or continental shelf. However, under the archipelago regime, a State may claim its sovereign rights based on a group of islands in its entirety, which consists of islands and their surrounding rocks. Additionally, under the archipelago regime, more waters, when applying archipelagic baselines, would be enclosed into archipelagic waters. In its Memorial, the Philippines defined the legal nature and status of each and every feature in the relevant waters of the SCS, and opposed continental States’application of archipelago regime, with a view to fragmentizing the whole Nansha Islands, from the perspective of analyzing the nature of some features. By doing so, it attempted to create a sovereignty vacuum in the SCS region, and undermine the integrity of China’s territorial sovereignty. As a matter of fact, the Philippines had already treated the islands in the SCS as groups of islands. For example, in its Presidential Decrees No. 1596 (released on 11 June 1978) and No. 1599 (released on 15 July 1978), the Philippines declared a cluster of 33 islands, islets and cays as its territory, and stated that such area constituted as a distinct and separate municipality of the Province of Palawan and shall be known as “Kalayaan Island Group”. On 10 March 2009, the Philippines adopted the Republic Act No. 9522 (i.e., An Act to Amend Certain Provisions of Republic Act No. 3046, as Amended by Republic Act No. 5446, to Def i ne the Archipelagic Baseline of the Philippines and for Other Purposes), which def i ned the baseline of territorial sea for “Kalayaan Island Group” and other islands.①GUO Yuan, Geopolitics and South China Sea Disputes, Beijing: China Social Sciences Press, 2011, pp. 273~281. (in Chinese)When examining the Philippines’ Submissions, the Tribunal was also aware of the unreasonableness in the Philippines’ def i nitionof the nature of some features of the Nansha Islands. “To the extent that a claim by the Philippines is premised on the absence of any overlapping entitlements of China to an exclusive economic zone or to a continental shelf, the Tribunal considers it necessary to consider the maritime zones generated by any feature in the South China Sea claimed by China, whether or not such feature is presently occupied by China.”①The Republic of the Philippines v. The People’s Republic of China, Award, 12 July 2016, para. 154, at https://pca-cpa.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/175/2016/07/PH-CN-20160712-Award.pdf, 24 March 2017.

C. The Philippines Claimed Its “Rights and Interests in the SCS” by Def i ning the Nature of Some Features Individually, with an Actual Purpose to Avoid the Application of the Declaration Excluding Compulsory Procedures under the UNCLOS to the Dispute between China and the Philippines

On 25 August 2006, China, in line with Article 298 of UNCLOS, delivered a declaration to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, excluding maritime disputes, such as those concerning sea boundary delimitations and historic rights, from compulsory arbitral procedures.②China Delivered a Declaration Excluding Compulsory Procedures under Article 298 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, at http://wcm.fmprc.gov.cn/pub/chn/gxh/ zlb/tyfg/t270754.htm, 24 March 2017. (in Chinese)However, the Philippines, disregarding China’s declaration above, unilaterally fi led a compulsory arbitration against China. As per the award of the SCS Arbitration, the Philippines requested, in Submissions No. 1~2, the Tribunal to decide that China’s “dashed line” was contrary to the UNCLOS and without lawful ef f ect, and to further deny China’s sovereignty and relevant rights in the SCS; Submissions No. 3~7 relate to the determination of the legal status of Huangyan Island, Meiji Reef, Ren’ai Reef, Zhubi Reef, Ximen Reef, Nanxun Reef and other features.③The South China Sea Arbitration, p. 5, at https://pca-cpa.org/wp-content/uploads/ sites/175/2016/07/PH-CN-20160712-Press-Release-No-11-English.pdf, 21 March 2017.These Submissions, prima facie, asked for protection of the rights and interests that the Philippines claimed in the SCS, but actually concerned the issue of maritime delimitation and the ownership of some features. The Philippines also made declarations under the UNCLOS. Article 4 of the Understanding Made upon Signature (10 December 1982) of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of the Philippines stated: “Suchsigning shall not in any manner impair or prejudice the sovereignty of the Republic of the Philippines over any territory over which it exercises sovereign authority, such as the Kalayaan Islands, and the waters appurtenant thereto.”①WU Shicun ed., Compilation of Documents on South China Sea Issues, Haikou: Hainan Press, 2001, p. 234. (in Chinese)Apparently, the Philippines attempted, using the pretext to protect its legal rights in the SCS through defining the nature of some features in the SCS, to demonstrate that its initiation of the arbitration was for the purpose of settling its dispute with China concerning the SCS, which was not a territorial sovereignty dispute beyond the jurisdiction of the Tribunal. By doing so, the Philippines aimed to avoid both China’s and the Philippines’ declarations described above.

II. China’s Position: the Nansha Islands Constitutes an Integral Archipelago

A. The Tribunal Cannot Deny the Integrity of the SCS Islands Based on Its Determination of Some Relevant Islands

In the SCS Arbitration, the Philippines requested the Tribunal to determine the nature of Huangyan Island, Meiji Reef, Ren’ai Reef, Zhubi Reef, Nanxun Reef, Ximen Reef, Chigua Reef and Huayang Reef, respectively. The Submissions show the Philippines’ position towards the nature of some relevant features (see Table 2). The Philippines contended that the features which were decided as “lowtide elevations” could neither generate territorial sea, EEZ or continental shelf, nor acquire sovereignty through occupation or other means, and those decided as “rocks” could not generate EEZ or continental shelf. The Philippines intended to deny the integrity of the SCS Islands by breaking up the whole into parts, and further to deny China’s sovereignty and jurisdiction over the SCS Islands and the adjacent sea areas. In accordance with Article 13 of the UNCLOS, since low-tide elevations may be submerged at high tide, they cannot have territorial sea, EEZ or continental shelf as islands. That is to say, the UNCLOS neither specif i ed that low-tide elevations were not territory, nor provided that the sovereignty over lowtide elevations cannot be acquired through occupation. It merely provided that the maritime entitlements of low-tide elevations were dif f erent from those of islands. In this case, even if a feature is def i ned as a low-tide elevation, it does not mean thatChina lost the territorial sovereignty over the feature. As far as “rocks” concern, a rock, under Article 121(3) of UNCLOS, is a special kind of islands. Since it cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of its own, a rock cannot generate EEZ or continental shelf, but it is entitled to territorial sea.①UNCLOS, at http://www.un.org/zh/law/sea/los/index.shtml, 22 March 2017.The UNCLOS failed to precisely define the rock and the condition of “sustaining human habitation or economic life of its own”, therefore, Chigua Reef and Huayang Reef cannot be def i ned as “rocks” in line with UNCLOS.

As per Article 46 of UNCLOS, archipelago should be natural features which form an intrinsic geographical, economic and political entity, or which historically have been regarded as such. Historically speaking, “Zhanghai” recorded in the Yiwu Zhi (Record of Foreign Matters), written by Eastern Han Yang Fu, refers to today’s SCS, which included the SCS Islands. In the Song Dynasty, Nansha and Xisha Islands got more vivid names: “Changsha”, “Qianli Changsha” and “Wanli Changsha” generally refer to Xisha Islands, and “Shitang”, “Qianli Shitang”and “Wanli Shitang” generally refer to Nansha Islands. Literatures and official documents thereafter also contain records about Xisha Islands and Nansha Islands. For example, in the Ming and Qing Dynasties, local chronicles of Guangdong Province enclosed “Qianli Changsha” and “Wanli Shitang” into the territory of the province.②YUAN Gujie, The Theory and Practice of the International Maritime Delimitation, Beijing: Law Press China, 2001, pp. 224~225. (in Chinese)It is not difficult to find from ancient Chinese documents that, China has, historically, always treated the SCS Islands as a whole, and named Xisha, Nansha, and other groups of islands in the SCS in their entirety.

Geographically, politically and economically, the SCS is a semi-enclosed marginal sea. The sea has over 200 features. According to their height dif f erence with the sea level, these features can be divided into fi ve categories: islands, cays, reefs, shoals and banks. Most of these features are submerged under water, with a few above the water. These islands, cays, reefs, shoals and banks are collectively called the “SCS Islands”. The seabed of the SCS is the basin of China. Continental shelves can only be found between the margin of the basin and its surrounding land. That is to say, the SCS Islands constitutes an independent geographical unit; Xisha, Zhongsha, Nansha and Dongsha Islands form, respectively, independent regions of their own, and have their own continental shelves. In this connection, the Nansha Islands mentioned in the Philippines’ Submissions, geographically, is a separate

unit.①GUO Yuan, Geopolitics and South China Sea Disputes, Beijing: China Social Sciences Press, 2011, pp. 301~302. (in Chinese)China fi rst developed and managed the SCS Islands. Chinese fi shermen had, as early as the Ming Dynasty, fi shed around and developed the SCS Islands. Geng Lu Bu (Manual of Sea Routes), a navigation guide which has been handed down by Hainan fi shermen from generation to generation, records, among others, voyages and sailing directions from Hainan Island to Xisha and Nansha Islands. This book also demonstrates that China has developed the SCS Islands since the Ming and Qing Dynasties. In the 1970s, an investigation team of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Xiamen University, found wells, huts, stone tablets and other things on Taiping Island, Zhongye Island, Nanwei Island and other features of the Nansha Islands, which were built by fishermen in the Ming and Qing Dynasties.②HAN Zhenhua ed., Collection of the Historical Materials of the SCS Islands, Shanghai: Orient Publishing Center, 1988, p. 519. (in Chinese)The governments of past dynasties have never stopped exercising sovereignty over and administrating the SCS Islands, and including Changsha and Shitang of the SCS Islands into the territory of China. Maps published after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China also indicate that the SCS Islands belongs to China. Chinese government also made statements on numerous occasions, reiterating China’s sovereignty over Nansha and Xisha Islands. In 1959, the Government of Hainan Administrative District of Guangdong Province, set up an administration office of Xisha, Nansha and Zhongsha Islands on Yongxing Island, responsible for exercising administrative jurisdiction over the SCS Islands. In 1988, Hainan Province included Xisha, Nansha and Zhongsha Islands as well as their adjacent waters into its jurisdiction. On 21 June 2012, upon the official approval of China State Council, the Sansha Office of Administration was replaced by prefecturelevel Sansha City. The government office was located on Yongxing Island of Xisha Islands. It follows that the SCS Islands, both geographically and historically, constitutes, in essence, a geographical, economic and political entity.

Table 2 The SCS Islands Involved in the Philippines’ Submissions

Source: Baidu encyclopedia, Wikipedia, Google map and the Philippines’ Memorial

B. Basis of International Law

1. The Legal Basis Supporting That Straight Baselines and Historic Rights Are Applicable to Continental States

The Government of Norway issued a royal decree on 12 July 1935, declaring that the waters four nautical miles northward of 66°28.8′ N should be the Norwegian fi sheries zone. In accordance with the decree, Norway drew its straight baselines joining 48 outermost points of its coasts and outermost land. The U.K. asserted that the method of straight baseline adopted by Norway was against the international law, and the drawing of such baselines would turn a part of the high seas into Norwegian fi sheries zone. Both States had negotiated over the issue for several times, but such negotiations failed. Under this circumstance, the U.K. fi led, in 1949, an application instituting proceedings before the ICJ against Norway. On 18 December 1951, the ICJ issued the judgment of the Fisheries Case (United Kingdom v. Norway), stating that the northern coastal zone of Norway was of a very distinctive configuration; the coast line was broken by large and deeply indented fjords and bays; the coastal zone concerned included numerous islands, islets, and reefs, forming a group of islands known by the name of the “skjærgaard”in Norway; there was no clear dividing line between land and sea of Norwegian coast; what really constituted the Norwegian coast line was the outer line of the“skjærgaard”. The ICJ held that the belt of territorial waters must follow the general direction of the coast; for the purpose of measuring the breadth of the territorial sea, the low-water mark was generally adopted in the practice of States, since this criterion was the most favourable to the coastal State and clearly showed the character of territorial waters as appurtenant to the land territory. However, the lowwater mark was not permanent. The sinuosities of coasts added to the complexity of the application of the low-water mark rule. Where a coast was deeply indented and cut into, or where it was bordered by a series of islands, a more practical method should be applied in delimiting the waters, including territorial sea, which gave a simpler form to the belt of territorial waters. This method consisted of selecting appropriate points on the low-water mark and drawing straight lines between them. Therefore, the ICJ found that the baselines drawn by Norway were not contrary to the international law.①Fisheries Case (United Kingdom v. Norway), pp. 127~130, at http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/ fi les/5/1809.pdf, 28 March 2017.

The Fisheries Case (United Kingdom v. Norway) played an essential role in clarifying rules of international law regarding the existing methods to draw baselines. After the end of the Fisheries Case, the method of straight baselines adopted by Norway, which took into account special geographical conditions, but was different from conventional method of baselines, has been widely adopted by other States. C. F. Amerasinghe, the president of the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, noted, “Although in the Norwegian Fisheries Case the Court was specif i cally considering only the questions of straight baselines for the purpose of measuring the territorial sea of f a deeply indented coast and of f a coast with archipelagoes, there were some general principles on the law of the territorial sea which it stated and which might prove of some assistance in regard to the problem of mid-ocean archipelagoes … [the belt of territorial waters must follow] the general direction of the coast.”①C. F. Amerasinghe, The Problem of Archipelagoes in the International Law of the Sea, International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 23, Issue 3, 1974, p. 544.The Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone, one of the four conventions adopted in the First United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea in 1958, clearly provides for, in Article 4, the method of drawing straight baselines for a fringe of islands along the coast. The judgment of the Fisheries Case could be said to serve as the basis for the method of straight baselines established in the Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone. In the Fisheries Case, the ICJ also considered Norway’s historic rights in the waters under question, contending that local populations of Norway had made a living upon fishing in this area for hundreds of years. Therefore, the delimitation method adopted by Norway was consistent with the international law. This case can provide, on the international level, support to China’s claim to historic rights within the “dashed-line” in the SCS. The fact that China’s coast lines are broken and bordered by numerous islands, in the words of Jeanette Green Field, indicates that China can apply straight baselines, which seems to comply with the principle reflected in the Fisheries Case.②Jeanette Green Field, China’s Practice in the Law of the Sea, Gloucestershire: Clarendon Press, 1992, p. 72.From the legal perspective, the UNCLOS merely provides for the archipelago regime for archipelagic States, without explicit provisions regarding the construction of the same regime for continental States. However, the ICJ judgment of the Fisheries Case and Article 4 of the Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone provide the legal basis for continental States to adopt straight baselines toencircle their mid-ocean archipelagoes.

2. Practices Relating to Straight Baselines Adopted by Other Continental States to Encircle Their Mid-Ocean Archipelagoes

Brownlee classified state practices into several categories, which include, among others, diplomatic instruments, policy statements, press releases, national legislation, international and domestic judicial precedents, treaties and other international instruments, as well as the resolutions of UN General Assembly concerning legal issues.①JIA Bingbing, Public International Law: Its Interpretation and Application in Time of Peace, Beijing: Tsinghua University Press, 2015, pp. 32~33. (in Chinese)A collation of the documents in association with the midocean archipelagic regime of some representative States (see Table 3) reveals: a) a great number of continental States had used straight baselines to encircle their midocean archipelagoes before the entry into force of the UNCLOS, and some adopted the regime of mixed baselines; b) after the entry into force of the UNCLOS, these States kept their original legislation, or adopted new legislation, in accordance with the UNCLOS, to apply straight baselines to encircle their mid-ocean archipelagoes. All these demonstrate that continental States’ adoption of straight baselines with respect to their mid-ocean archipelagoes has become stable state practices.

A number of States not only articulated in their national laws that they adopted straight baselines with respect to their mid-ocean archipelagoes, but also delivered notes to UN Secretary-General to ask for the same. On 9 March 2011 Ecuador sent a note to the UN Secretary-General asking to record and disseminate its Executive Decree No. 450 of 2 August 2010, which approved and ordered publication of Ministerial Agreement 0081 of 12 July 2010 and Nautical Chart IOA42. The attached map clearly showed Ecuador’s straight baselines around its oceanic Galápagos Islands.②HONG Nong, LI Jianwei and CHEN Pingping, The Concept of Archipelagic State and the South China Sea: UNLCOS, State Practice and Implication, China Oceans Law Review, No. 1, 2013, p. 223.The maps attached in the Submission made by Portugal, in May 2011, on the outer limits of continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines, to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) clearly show that Portugal used both straight baselines and normal baselines in practice. The Gazetteer of India dated 11 May 2009 (No. 736) stated that straight baselines were applicable to Lakshadweep. On 29 January 2010, India deposited with the UN Secretary-General a list of geographical coordinates of points def i ning

the baselines of Lakshadweep as well as its nautical chart.①M.Z.N.76.2010.LOS of 17 February 2010, at http://www.un.org/Depts/los/LEGISLATION ANDTREATIES/PDFFILES/mzn_s/mzn76ef.pdf, 29 April 2017.

Table 3 Practices of Representative States Relating to the Establishment of Archipelago Regime

Kerguelen Islands (France)31sectionsofstraightbaselinesconnecting32basepointsselectedwere drawnfortheKerguelenIslands.Thelongestsegmentwasupto19.7nautical miles.DecreeNo.78-112of1978 Lakshadweep(India) Whendrawingthebaselineoftheterritorialseaofanarchipelagoand makingtherelevantmaritimeclaims,oneshouldtreatthearchipelagoasawhole,ratherthandisintegrateitintopieces.13basepointswereselectedfort measuringtheterritorialseaoftheLakshadweepArchipelago.Thestraighbaselinesconnectingthesepointswerearound560nauticalmilesintotal. 1.DecreeNo.80of28May19762.GazetteerofIndiadated11 May2009(No.736) Mixed baselines Faroes Island(Denmark) 10basepointswereselectedformeasuringtheterritorialseaoftheFormal aroeIslands.Themethodofusingstraightbaselinestogetherwithnbaselineswasadoptedtodelineate12nauticalmilesofterritorialseaoftheFaroeIslands. 1.DecreeNo.130of27April19592.DecreeNo.156of24April19633.ActNo.200of7April1999 4.DecreeNo.240of30April20025.ExecutiveOrderNo.306of 16May2002 Azores(Portugal)Thebaselineof Azoreswascomposedofnormalbaselinesandstraight baselines.TheAzoresIslandswasdividedintothreeparts,and29basepoints wereselectedformeasuringitsterritorialsea.Straightbaselineswereappliedtothethreepartsrespectively.Decree-LawNo.495/85of29 November1985

3. Relevant Provisions of China’s Domestic Law and State Practices with Respect to the Xisha Islands

The activities of the Chinese people on the Xisha Islands took place earlier than the adoption of the UNCLOS. China did not, in this connection, invoke UNCLOS Article 7 as the international legal basis. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, Chinese government promulgated in 1958 the Declaration of the Government of the People’s Republic of China on China’s Territorial Sea. The Declaration states that the breadth of the territorial sea of China shall be 12 nautical miles drawn by the method of straight baselines. This regime of territorial sea applies to Taiwan and SCS Islands. It conf i rmed, through government statements, that China had owned the SCS Islands and its adjacent waters since ancient times. In 1973, Chinese delegation sent the Working Paper on Sea Area within National Jurisdiction to the United Nations Sea-Bed Committee, which stated that “a group or a fringe of islands that are relatively close to each other may be considered as a single entity when drawing territorial seas.”②ZHAO Lihai, On Some Legal Issues Relating to the SCS Islands, Law and Social Development, No. 4, 1995, pp. 56~57. (in Chinese)In 1992, Chinese government formulated the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone. Article 2 of the Law enumerates the archipelagoes and islands belonging to China. It reiterates and conf i rms, through legislation, that the SCS Islands forms an inherent part of Chinese territory. Further, it paved the way legally for the drawing of the baselines of the territorial sea surrounding the Nansha Islands. On 15 May 1996, China promulgated the Declaration of the Government of the People’s Republic of China on the Baselines of the Territorial Sea, announcing the baselines of part of its territorial sea adjacent to the mainland and those of the territorial sea adjacent to its Xisha Islands. Part 2 of the Declaration marked 28 base points of the territorial sea around the Xiasha Islands. That is to say, China treats the Xisha Islands as an integrated whole. The baseline of the territorial sea adjacent to the Xisha Islands is composed of straight baselines connecting the base points selected for this group of islands.

III. Signif i cances of Establishing a Mid-Ocean Archipelagic Regime in the SCS

A. To Delineate the Maritime Zones of a Group of Islands in Its Entirety, Making China’s Sovereignty Clear in the SCS

The islands and reefs scattered in the SCS are great in number. Take the most controversial Nansha Islands for example. Although the features in the Nansha Islands are large in number, only 36 of them are above water at ordinary times, and merely 25 are above water at high tide. A feature of the Nansha Islands, if def i ned individually, will be difficult to meet the standard of “island” under Article 121 of the UNCLOS. It would further lead the international community to challenge the legal status of the feature, and reduce the jurisdictional waters of China in the SCS. In other words, it would be difficult for the feature to have its own EEZ, continental shelf, and even territorial sea. If baselines are drawn separately for each and every feature in the SCS, the territorial sea of China in the SCS would be carved up. In that case, territorial sea would overlap with the high seas, and the scope of China’s sovereignty in the SCS would further be blurred. Therefore, to establish a regime of mid-ocean archipelago in the SCS has far-reaching impacts and signif i cances. Specifically, China should treat the SCS Islands as several separate groups of islands, and then draw the baseline of the territorial sea for each group of islands in its entirety by connecting the base points selected. By doing so, China may change the embarrassing position of a feature in a sovereignty dispute, but also clarify the scope of China’s sovereignty in the SCS.

B. To Ef f ectively Settle the Dispute Between the Philippines and China in the SCS

The Sino-Philippine dispute in the SCS mainly concerns the sovereignty of some features and maritime delimitation. The baselines of the Philippine territorial sea were drawn in accordance with the archipelagic doctrine. All the waters centering the Philippine archipelago, which lie beyond the outermost islands of the Philippine archipelago but within the treaty boundary, are called the Philippine territorial sea. The “treaty boundary” means the outer limits of the Philippine territorial sea consisting of all the waters mentioned in the Treaty of Paris of 1898 between Spain and the United States, the Treaty of Washington (1900) betweenSpain and the United States, and the Convention between the United States and Great Britain (1930). The method that the Philippines employed to draw the baselines of its territorial sea would turn a large area of the high seas lying between the islands of the Philippine Archipelago into its jurisdictional waters, and turn the waters enclosed by the baselines into its internal waters. Additionally, the Philippines passed legislation regarding the archipelagic baselines, and drew its EEZ and continental shelf from the baselines. By doing so, the Philippines included 33 of Chinese islands, reefs, shoals and banks in the Nansha Islands into its insular territory, which, in turn, made the outer limits of its EEZ intrude into the traditional boundary line of China. In order to protect its alleged “sovereignty in the SCS”, the Philippines, on the one hand, opposed the establishment of an archipelagic regime by continental States, like China, for their mid-ocean archipelagoes, on the pretext that the archipelagic regime applied only to archipelagic States and the UNCLOS failed to provide that this regime was applicable to continental States. On the other hand, the Philippines proposed to determine the nature of some features in the SCS individually. If some of these features are def i ned as rocks or low-tide elevations, it would have great impacts on the maritime delimitation between China and the Philippines. Specif i cally, China may not claim EEZ and continental shelf for these features, if they are def i ned as rocks or low-tide elevations. The Philippines attempted to, through denying the entirety of the SCS Islands, limit or reduce the scope of China’s sovereignty in the SCS, and “legitimize” its illegal occupation of some features in the SCS. Although the UNCLOS did not express that continental States may draw archipelagic baselines, it did not also deny the continental States of their right to construct an archipelagic regime for their mid-ocean archipelagoes. That is to say, continental States may possibly draw straight baselines for their distant archipelagoes. The waters enclosed by the baselines should be internal waters or territorial sea, rather than archipelagic waters. China may also use the method of straight baselines to draw the archipelagic baselines with respect to its groups of islands in the SCS. Under the archipelagic regime, a string of rocks, reefs, islands, and other features forms an archipelago, which should be treated as a whole in maritime delimitation. Therefore, by establishing a mid-ocean archipelagic regime, China may exercise absolute sovereignty over the SCS Islands, and further foil the Philippines’ plot to occupy the SCS Islands of China.

C. To Break Through the Island Chain Blockade Set by the United States

The geographical location of the SCS is of great importance. It is not only a key sea passage connecting Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean, but also a vital transportation hub connecting Oceania with the continent of Asia. The “island chain strategy” prepared by the United States constitutes an essential part of its Asia-Pacific strategy. The island chain, in line with the marine topographic features of the Asia-Pacif i c region, is divided into fi rst and second island chains. The “island chain strategy” is designed to block the sea passage of China, Russia and other States. The SCS, a vital pivot on the first island chain, together with the Korea Peninsula, forms the so-called “crescent defensive line”, which was devised to obstruct China at the sea. Consequently, the SCS holds a very important position in the “island chain strategy” of the United States. If the SCS is not under the control of China, the United States may completely contain China within the fi rst island chain; otherwise, the “crescent defensive line” would be no longer in existence, the “island chain strategy” made by the United States would fail, and the United States would be compelled to retreat to the second island chain with respect to its defence in the Asia-Pacif i c region. The Philippines, as a State with weak comprehensive national power, tried every means to persuade great powers outside the region to intervene in the SCS disputes, with a view to protecting its alleged “sovereignty” in the SCS, and achieving its strategic goal in the region. The United States supported the Philippines’ occupation of China’s islands and reefs in the SCS, with the purpose to contain China through the hands of the Philippines, to deny China’s sovereignty in the SCS region, and further to safeguard its “island chain strategy”. Additionally, the majority of the raw materials imported from the Asian-Pacif i c region are shipped to the United States through the sea routes in the SCS. The destruction of these routes would affect the economic development of the United States, and hinder the import of most oil and gas to Japan. Therefore, the United States repeatedly claimed that its main concern in the SCS region was to keep the international waterway in the region unobstructed. In response to that, the Chinese government had, on many occasions, expressed that China’s protection of its sovereignty over the Nansha Islands and the relevant maritime entitlements would not prejudice the freedom of navigation and overf l ight enjoyed by foreign ships or aircraft under international law.

If a mid-ocean archipelagic regime is constructed in the SCS, China may,when drawing the baselines of territorial sea and claiming the relevant maritime entitlements, treat each of certain groups of islands in the SCS as a whole. By doing so, China could effectively refute the Philippines and the United States, which denied and challenged China’s sovereignty in the SCS by taking advantage of the vacuum left by the UNCLOS. In the meantime, China may, by reference to the provisions of the UNCLOS, design right of innocent passage and right of archipelagic sea lanes passage in relevant waters. The sea lanes designated by China for the free passage of foreign ships are, certainly, lanes suitable for safe navigation, which are decided by the sovereign State after comprehensive considerations. China’s management and maintenance of these lanes would help ensure the safety of international navigation. In other words, it would guarantee China’s absolute sovereignty in the region, and also ensure the free passage and safety of foreign ships in the region. In a word, to establish a mid-ocean archipelagic regime in the SCS would not only protect China’s sovereignty in the SCS region, but also break the island chain blockage set up by the United States.

D. To Advance the Development of the Current Rules of the Law of the Sea

More than three decades have passed since the adoption of the UNCLOS in 1982. The UNCLOS established the basic legal framework for the exploitation and management of internal waters, territorial sea, contiguous zone, continental shelf, EEZ and other marine areas. However, its provisions concerning the archipelagic regime are suffered from defects, since this regime is a result of compromises. Due to the objections from some States, the controversies over the mid-ocean archipelagoes of continental States were put of f during the draft of the text of the Convention. As many publicists honestly noted, that the UNCLOS avoided to addressing the question whether the archipelagic regime should be applicable to the mid-ocean archipelagoes of continental States was decided by the inf l uences of political and diplomatic factors.①BU Lingjia and HUANG Jingwen, The Issue Concerning the Continental States’ Application of Straight Baselines to Their Distant Archipelagoes, Sun Yat-sen University Law Review, No. 2, 2013, p. 110. (in Chinese)An increasing number of States have applied the straight baselines to draw the waters of their mid-ocean archipelagoes. Nevertheless, the UNCLOS still inf l exibly sticks to the consensus reached in 1982, and failedto, in line with state practices and the change of international customs, timely adjust itself. For the sake of its national interests, the Philippines construed the UNCLOS in bad faith, derogating from the principles and spirit of the Convention. Making use of the compromises found in and the lagging nature of the UNCLOS, the Philippines sought the legal basis from international law (the UNCLOS) to support its occupation of China’s islands in the SCS, which further escalated the disputes in the SCS. Laws, under most cases, may gradually (but not fundamentally) change on the basis of existing conventions. Some values and concepts, which were originally expressed by soft laws without binding force, may later affect public opinions, political agendas and fi ll up the gap of treaty law. Apparently, States are not able to negotiate formally over all emerging issues relating to the oceans and seas, as such, the amendment mechanism well designed under the UNCLOS①UNCLOS, Articles 155, 312~314, at http://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/ texts/unclos/closindx.htm, 22 March 2017.will be difficult to be put into use. In this case, the adoption of new regional or global treaties addressing such issues, as well as state and intergovernmental practices with respect to such issues, would push the creation of new rules of the law of the sea. China should apply the mid-ocean archipelagic regime of continental States, which was derived from the regime of archipelagic State, to its SCS Islands. In doing so, China does not merely focus on its sovereignty and sovereign rights in the SCS area; instead, it endeavors to fi nd the root causing the fi erce conf l icts in the SCS, and then explore practicable solutions based on it. China should, under the legal framework of mid-ocean archipelagoes, work on its initiative to cooperate with the States concerned to peacefully settle their disputes in the SCS, and further to contribute to the development of the rules of the law of the sea.

IV. Suggestions on the Construction of an Archipelagic Regime for the Nansha Islands Involved in the Sino-Philippine Arbitration

A. Drawing of the Baselines of the Nansha Islands

The baselines of the Nansha Islands should be drawn by using the method of straight baselines, which is generally adopted in the practice of States. The Nansha Islands is eligible for applying the straight baselines on the followinggrounds. Firstly, geographically speaking, in accordance with the ICJ judgment of Norwegian Fisheries Case, the method of straight baselines is applied where a coast was deeply indented and cut into, or where it was bordered by a fringe of islands; the Nansha Islands consisting of many features is sinuous in conf i guration, therefore it meets the condition “where a coast was deeply indented and cut into”. Secondly, the ICJ asserted that the belt of territorial waters must follow the general direction of the coast. The sea areas lying within the baselines should be sufficiently closely linked to the land domain to be subject to the regime of internal waters. In this connection, China’s application of the straight baselines to the Nansha Islands shows, precisely, its respect to the natural conf i guration of the coasts and features of the Nansha Islands, as well as the full consideration to the geographic direction of the Nansha Islands. Thirdly, the Philippines’ request to def i ne the nature of each and every feature in the Nansha Islands individually in the SCS Arbitration, as a matter of fact, ignored the integrity of the Nansha Islands. The islands, reefs, shoals and banks constituting the Nansha Islands, as well as the adjacent waters, have formed an intrinsic geographical, economic and political entity, or historically have been regarded as such.①ZHENG Yuchen, The Evolution of the Regime of Mid-Ocean Archipelago of Continental States and Its Implication for China’s South China Sea Islands (Master Dissertation), Beijing: China Foreign Af f airs University, 2016, p. 34. (in Chinese)The Nansha Islands has been considered as a single entity, which has also been acknowledged by the academia of international law and the international community. Currently, the baselines of mid-ocean archipelagoes that have been published were drawn following the principle of integrity. In this regard, China also conf i rmed, through legislation, the integrity of a group of islands in the Working Paper on Sea Area within National Jurisdiction.②Article 1(6) of the Working Paper on Sea Area within National Jurisdiction states: “a group or a fringe of islands that are relatively close to each other may be considered as a single entity when drawing territorial seas.”The Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone, adopted on 25 February 1992, reconfirmed that the method of straight baselines was applied to draw the baselines of the groups of islands in the SCS.

With regards to the reasonable application of the straight baselines, if the Nansha Islands is treated as a whole, and its baselines are drawn by the method of straight baselines joining the appropriate points around the outermost features of the Nansha Islands, the sea areas enclosed by the baselines may possibly become too large. This would affect the maritime interests of other States bordering theSCS, such as the freedom of navigation and the exploitation of marine resources, and then invite their criticism. Although the Nansha Islands should be treated as a single entity, due to the large number of features in this group of islands and its complex situation, this group of islands should be subdivided into smaller groups when drawing baselines; additionally, not all the waters enclosed by the baselines should be def i ned as “internal waters”.

B. To Fully Prepare Legally for the Establishment of an Archipelagic Regime, and to Follow the Trend of Protecting Maritime Rights and Interests Through Laws

The law of the sea serves as the basis for balancing the maritime rights and interests among different States. The UNCLOS set out the legal framework for the management and exploitation of the oceans and seas. Under the current circumstance where an increasing number of States tend to protect their maritime rights and interests through laws, the marine disputes between States can hardly be settled without a complete legal system of the sea. Apart from that, the UNCLOS is not a static legal system; instead, it needs to be improved in practice. China must follow the trend to protect its own maritime rights and interests through laws. Since the UNCLOS is the “constitution of the oceans” agreed by States upon negotiations, it inevitably contains provisions resulting from compromises. Taking into account the interests of all the parties concerned, the UNCLOS laid out some ambiguous provisions, which could be interpreted by States from different standpoints for their own interests. Hence, China needs to put more efforts into the research and application of the UNCLOS, striving to make full use of the legal regimes under the UNCLOS in practice. For example, China should do further research into the legal status of the “dashed line” in the SCS, and ascertain China’s historic title in the relevant waters. It should fi nd convincing grounds from jurisprudence, seeking to pacif i cally settle its disputes with other States. China’s legal system with respect of the seas and oceans, although established preliminarily, is problematic and deficient. For example, the Declaration of the Government of the People’s Republic of China on the Baselines of the Territorial Sea, 1996, announced the baselines of part of its territorial sea adjacent to the mainland and those of the territorial sea adjacent to its Xisha Islands, and stated that the Chinese government would announce the remaining baselines of China. Nonetheless, after two decades, China still has not declared the baselines of its territorial seafrom Haiyang Island to Chengshantou Cape, nor the baselines encircling other groups of islands in the SCS. In contrast, many continental States with mid-ocean archipelagoes had enacted the relevant laws before the adoption of the UNCLOS. Therefore, the lagging of China’s marine legislation is quite obvious. However, the implementation and performance of the UNCLOS depends on the construction of the pertinent national legal system. In other words, the success of the UNCLOS depends, to a great extent, on the level of legal construction of States. In recent years, the marine landscape and interests, both on the national and international level, changed immensely. Facing new situation and new problems, China should adopt national laws to improve and clarify the equivocal, vague or even defective provisions of the UNCLOS, such as the mid-ocean archipelagic regime for continental States. China should set up such a complete legal system of the sea that it may have laws to follow in the exploration and exploitation of the seas and the protection of its marine rights and interests, and that it may maximally protect its sovereignty over the SCS Islands. Aside from that, China should also actively participate in the discussion on and formulation of the international regulations concerning the oceans and the seas organized by the United Nations. It should take the initiative to attend international academic symposiums, with the aim to make its standpoints understood, and make such international regulations ref l ect China’s reasonable claims of rights.

C. The Strategy That China Should Adopt in Its Dispute with the Philippines in the SCS under New Circumstances

The Philippines has always had severe dispute with China over the sovereignty of some features in the SCS. In recent years, the Philippines, supported by exterritorial powers, challenged China continuously on the SCS issue. On 30 June 2016, Duterte was elected as the new president of the Philippines. After taking office, Duterte, reversing the pro-American policies pursued by the Aquino III administration, pursued a foreign policy independent of the United States. He harbored no hope of solving the SCS dispute through international arbitration, although he also acknowledged the result of the SCS Arbitration. Duterte repeatedly stressed that the Philippines would not open fire with China, and it was willing to jointly explore the oil and gas resources in the SCS with China through joint ventures. He also expressed its welcome for China to assistthe Philippines in improving its infrastructures.①Duterte Favors Making Deal with China over Dispute, at http://globalnation.inquirer. net/138487/duterte-favors-making-deal-china-dispute, 31 March 2017.Although it is not possible for the Duterte administration to distance itself from the United States, it changed its strategy, aiming to restore its relationship with China without offending the United States. That is to say, it endeavors to obtain the benef i ts from both sides: to get the security guarantee provided by the United States on the one hand, and to take a free ride in the express train of China in economic development on the other hand.②ZHANG Jie, The South China Sea Game: U.S. – Philippines Military Alliance and Sino-Philippine Relations Adjustment, Pacif i c Journal, No. 7, 2016, p. 33. (in Chinese)During President Duterte’s visit to China last October, the two heads of State reached the important consensus to properly handle the SCS issue, taking the two sides back to the right track of properly handling the SCS issue through dialogue and consultation.③Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Lu Kang’s Regular Press Conference on 30 March 2017, at http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/xwfw_665399/s2510_665401/2511_665403/t1450255. shtml, 30 May 2017.The Joint Statement of the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of the Philippines specially discussed the SCS issue. Its Article 40④Joint Statement of the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of the Philippines, Article 40, “Both sides exchange views on issues regarding the South China Sea. Both sides affirm that contentious issues are not the sum total of the China-Philippines bilateral relationship. Both sides exchange views on the importance of handling the disputes in the South China Sea in an appropriate manner. Both sides also reaffirm the importance of maintaining and promoting peace and stability, freedom of navigation in and overflight above the South China Sea, addressing their territorial and jurisdictional disputes by peaceful means, without resorting to the threat or use of force, through friendly consultations and negotiations by sovereign states directly concerned, in accordance with universally recognized principles of international law, including the Charter of the United Nations and the 1982 UNCLOS.”articulates that the territorial and jurisdictional disputes should be addressed by sovereign States directly concerned by peaceful means through friendly consultations and negotiations. It amounts to a further consolidation of the official positions of both States through government documents. It implies that, currently, there is room for change in the Sino-Philippine relations. However, under current circumstance, it is still difficult for the two States to reach an agreement within a short period, due to their great dif f erences over sovereignty issues. And cooperation between the two would never take place if cooperation can only be carried out after the resolution of their dispute. Comparatively speaking, “shelving dif f erences and seeking joint development” can be used as a feasible solution to their dispute in the SCS for the time being. China should reconsider this strategy in the new situation.